ʻAoa, American Samoa

ʻAoa | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Coordinates: 14°15′56″S 170°35′2″W / 14.26556°S 170.58389°W | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.66 sq mi (1.72 km2) |

| Elevation | 3 ft (1 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 344 |

| • Density | 520/sq mi (200/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−11 (Samoa Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 96799 |

| Area code | +1 684 |

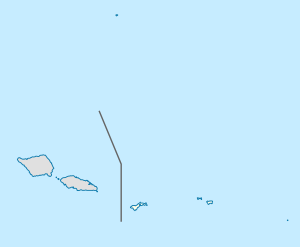

ʻAoa is a village on the north-east coast of Tutuila Island, American Samoa.[1] It is located on the north coast, close to the island's eastern tip, at a narrowing of the island and is connected by road with Amouli on the south coast. ʻAoa is the oldest site on Tutuila to yield ceramics. Located in a large U-shaped valley on the northeast coast of the island, ʻAoa sits on a wide, sandy beach fronted by a large, deep bay. Fresh water is supplied by a steady river which runs through the village.[2] It is located in Vaifanua County.[3]

It is one of few places in American Samoa with remaining patches of mangrove forest. The largest such forests are found in Nuʻuuli and Leone.

ʻAoa is adjacent to Faʻalefu, a neighboring village which shares ʻAoa Bay.

History

[edit]In prehistoric times, ʻAoa village stands out for several reasons. It is the only known ceramic residential site on Tutuila Island, and its earliest deposits — around 3,000 years old — are among the oldest in the Sāmoan Islands. In addition, it contains a greater abundance of volcanic glass and basaltic artifacts than any other residential site in the Sāmoan Islands.[4]

Over 40 ancient star mounds have been discovered in the bush near ʻAoa. Village chiefs believe these elevated stone platforms were used in the ancient chiefly sport of pigeon-snaring. Archeologists believe they served as military lookouts due to their placement at strategic vantage points, perhaps as a military lookout for enemy canoes. Besides the star mounds, lepita pottery has been discovered in ʻAoa. Some estimates date some of the potshards discovered here to 2000 BCE, while most of the scientific community dates them to 500 BCE. The Department of Tourism operated a camp site here complete with showers and barbecue facilities. The campsite was however closed as of 1994.[5]

In 1892, the village of ʻAoa became the focal point of significant conflict. The unrest originated among supporters of High Chief Lei’ato, whose lineage is traditionally believed to have begun in ʻAoa. Lei’ato’s son had previously established a secondary lineage in Fagaʻitua. Over time, the Fagaʻitua branch gained prominence, with their matai rising to become the principal high chief for the entire eastern region of Tutuila. That year, the residents of ʻAoa sought to appoint an alternative high chief, challenging the established authority of the Fagaʻitua lineage. In response, Lei’ato of Fagaʻitua took decisive action by mobilizing warriors and launching a dawn raid on ʻAoa. This attack resulted in the deaths and injuries of several villagers. The British consulate intervened after the looting of a store owned by A. Young, an English trader in ʻAoa, and the slaughtering of his pigs. Additionally, relatives and supporters of Lei’ato from the Western District traveled east to join the conflict.[6]

In 1942, Austrian immigrant to the U.S., Karl Paul Lippe, was billeted in the village of ʻAoa. He had joined the U.S. Marine Corps and was sent to the Samoan Islands. In the village of ʻAoa, Lippe was embraced by High Chief Logo, who asked him to move into his fale. Eventually, Lippe fell in love with Malele, the chief's daughter. At the time the young Marine was called off to war, his wife was pregnant. After World War II, he made an attempt to visit American Samoa, but was told no one was allowed to settle in the islands without the Naval Governor's permission. His request was initially denied but was later accepted when he managed to get in contact with the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington.[7]

In 1989, a hurricane severely damaged 'Aoa village, destroying numerous homes and driving waves through the community to the base of Olomoana Mountain. Another hurricane hit the village in December 1991.[8]

In 2016, the village of ʻAoa initiated discussions on the possibility of re-closing the Aoa Village Marine Protected Area (VMPA) to fishing, after it had been open for four years. Proponents of reinstating fishing restrictions expressed concerns about the impact of overfishing on marine resources, advocating for conservation measures to ensure the sustainability of ocean life for future generations. Opponents of the closure emphasized the importance of daily fishing to provide for their families, highlighting the economic and subsistence needs of the community. A proposed compromise included a zoning plan that would allow fishing in designated areas, while potentially banning certain methods such as spearfishing and permitting only rod-and-reel fishing. The proposal required approval by the village council, and the process was expected to be prolonged due to the divergent views within the community.[9]

Geography

[edit]The steep and mountainous terrain of the northern coast separates the villages along this coast from Pago Pago and other Tutuila villages. A narrow and unpaved road (as of 1975) connects ʻAoa with its neighboring villages.[10]

'Aoa village rests in a horseshoe-shaped bay and valley along the island’s northern coast, where the land narrows to less than two kilometers. Steep ridges extending from Olomoana Mountain in the east and Leʻaeno Mountain in the west shape the 'Aoa Valley. 'Aoa itself spans the eastern portion, just northwest of Olomoana Mountain, which rises about 326 meters behind the village. To the west, a smaller group of homes forms the village of Faʻalefu. In total, six streams course through the valley.[11]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Population[12] |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 344 |

| 2010 | 855 |

| 2000 | 507 |

| 1990 | 491 |

| 1980 | 304 |

| 1970 | 271 |

| 1960 | 202 |

| 1950 | 194 |

| 1940 | 141 |

| 1930 | 137 |

References

[edit]- ^ Shaffer, Robert J. (2000). American Samoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag. Island Heritage. Page 210. ISBN 9780896103399.

- ^ Shaffer, Robert J. (2000). American Samoa: 100 Years Under the United States Flag. Island Heritage. Page 36. ISBN 9780896103399.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (2000). The Samoa Islands. University of Hawaii Press. Page 424. ISBN 9780824822194.

- ^ Clark, Jeffrey T. and Michael G. Michlovic (1996). “An Early Settlement in the Polynesian Homeland: Excavations at 'Aoa Valley, Tutuila Island, American Samoa”. Journal of Field Archaeology. Volume 23, No. 2. Page 152. ISSN 0093-4690.

- ^ Swaney, Deanna (1994). Samoa: Western & American Samoa: a Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet Publications. Page 178. ISBN 9780864422255.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Pages 95-96. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Kennedy, Joseph (2009). The Tropical Frontier: America's South Sea Colony. University of Hawaii Press. Page 214. ISBN 9780980033151.

- ^ Clark, Jeffrey T. and Michael G. Michlovic (1996). “An Early Settlement in the Polynesian Homeland: Excavations at 'Aoa Valley, Tutuila Island, American Samoa”. Journal of Field Archaeology. Volume 23, No. 2. Page 153. ISSN 0093-4690.

- ^ Poblete, JoAnna (2020). Balancing the Tides: Marine Practices in American Sāmoa. Sustainable History Monograph Pilot. Page 117. ISBN 9780824883515.

- ^ United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Pacific Ocean Division (1975). Water Resources Development by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in American Samoa, 1975. Division Engineer, U.S. Army Engineer Division, Pacific Ocean, Corps of Engineers. Page 36.

- ^ Clark, Jeffrey T. and Michael G. Michlovic (1996). “An Early Settlement in the Polynesian Homeland: Excavations at 'Aoa Valley, Tutuila Island, American Samoa”. Journal of Field Archaeology. Volume 23, No. 2. Pages 153-154. ISSN 0093-4690.

- ^ "American Samoa Statistical Yearbook 2016" (PDF). American Samoa Department of Commerce. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-14. Retrieved 2019-07-25.