Hand fan

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

A handheld fan, or simply hand fan, is a broad, flat surface that is waved back-and-forth to create an airflow. Generally, purpose-made handheld fans are folding fans, which are shaped like a sector of a circle and made of a thin material (such as paper or feathers) mounted on slats which revolve around a pivot so that it can be closed when not in use. Hand fans were used before mechanical fans were invented.

Fans work by utilizing the concepts of Thermodynamics. On human skin, the airflow from hand fans increase the evaporation rate of sweat, lowering body temperature due to the latent heat of the evaporation of water. It also increases heat convection by displacing the warmer air produced by body heat that surrounds the skin, which has an additional cooling effect, provided that the ambient air temperature is lower than the skin temperature, which is typically about 33 °C (91 °F).

Next to the folding fan, the rigid hand screen fan was also a highly decorative and desired object among the higher social classes[citation needed]. They serve a different purpose to the lighter, easier to carry hand fans. Hand screen fans were mostly used to shield a lady's face against the glare of the sun or fire.

History

[edit]Africa

[edit]Hand fans originated about 4000 years ago in Egypt. Egyptians viewed them as sacred objects, and the tomb of Tutankhamun contained two elaborate hand fans.[1]

Ancient Europe

[edit]

Archaeological ruins and ancient texts show that the hand fan was used in ancient Greece at least from the 4th century BC and was known as a rhipis , rhipister or rhipidion (Ancient Greek: ῥιπίς, ῥιπιστήρ or ῥιπίδιον).[2][3] Fans were also used to keep flies away (like a fly-flapper), this kind of fan was less stiff and was named μυιoσόβη.[2] Another use for a fan was to fan the flame, e.g. in cookery or at the altar.[2]

Christian Europe's earliest known fan was the flabellum (ceremonial fan), which dates from the 6th century. It was used during services to drive insects away from the consecrated bread and wine. Its use died out in western Europe, but continues in the Eastern Orthodox and Ethiopian Churches.

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]

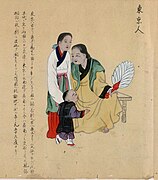

There were many kinds of fans in ancient China.[4] The Chinese character for "fan" (扇) is etymologically composed of the characters for "door" (戶) and "feather" (羽). Historically, fans have played an important aspect in the life of the Chinese people.[5] The Chinese have used hand-held fans as a way to relieve themselves during hot days since the ancient times; the fans are also an embodiment of the wisdom of Chinese culture and art.[6] They were also used for ceremonial and ritual purposes[7] and as a sartorial accessory when wearing hanfu.[5] They were also carriers of Chinese traditional arts and literature and were representative of its user's personal aesthetic sense and their social status.[7] Specific concepts of status and gender were associated with types of fans in Chinese history, but generally folding fans were reserved for males while rigid fans were for females.

In ancient China, fans came in various shapes and forms (such as in a leaf, oval or a half-moon shape), and were made in different materials such as silk, bamboo, and feathers.[8] So far, the earliest fans that have been found date to the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period. It was suggested by the Cultural Relics Archaeology Institute of Hubei Province that these fans were made of either bamboo or feathers and were oftentimes used as burial objects in the State of Chu.[9]: 3–4 The oldest existing Chinese fans are a pair of woven bamboo, wood or paper side-mounted fans from the 2nd century BC.[10] The Chinese form of the feather fan, known as yushan, was a row of feathers mounted in the end of a handle. The arts of fan making eventually progressed to the point that by the Jin dynasty, fans could come in different shapes and could be made in different materials.[9]: 5 The selling of hexagonal-shaped fan was also recorded in the Book of Jin.[9]: 5

In later centuries, Chinese poems and four-word idioms were used to decorate fans, using Chinese calligraphy pens. The Chinese dancing fan was developed in the 7th century.

- Chinese hand fans

-

Statue of Zhuge Liang holding a feather fan inside a temple

-

An hexagonal rigid fan with a Chinese painting of a cat and a calligraphy, late Qing dynasty

Wumingshan

[edit]

The most ancient ritual Chinese fan is the wumingshan, also known as zhangshan, which is believed to have been invented by Emperor Shun.[7] It is characterized with a long handle and the fan looks like a door in shape.[7] This type of fan was used for ceremonial purposes.[7] While its shape evolved throughout the millennia, it remained used as a symbol of imperial power and authority; it continued to be used until the fall of the Qing dynasty.[7]

Tuanshan

[edit]Silk round-shaped fans are called tuanshan (团扇), also known as "fans of reunion"; it is a type of "rigid fan".[5][9]: 5 These types of fans were mostly used by women in the Tang dynasty and were later introduced into Japan.[11] These round fans remained mainstream even after the growing popularity of the folding fans.[9]: 8, 12–16 Round fans with Chinese paintings and with calligraphy became very popular in the Song dynasty.[9]: 8, 12–16 During the Song dynasty, famous artists were often commissioned to paint fans. Lacquer fans were also one of the unique handcraft of the Song dynasty.[6]: 16

Chinese brides also used a type of moon-shaped round fan in a traditional Chinese wedding called queshan.[7] The ceremonial rite of queshan was an important ceremony in Chinese wedding: the bride would hold it in front of her face to hide her shyness, to remain mysterious, and as a way to exorcise evil spirits.[7] After all the other wedding ceremonies were completed and after the groom had impressed the bride, the bride would then proceed in revealing her face to the groom by removing the queshan from her face.[7]

- Chinese hand fans

-

A round fan with a Chinese painting, a type of rigid fan; late Qing dynasty.

-

A woman holding a flat oval fan with a Chinese painting from the painting "Appreciating Plums" by Chen Hongshou (1598–1652)

Pukuishan

[edit]

Another popular type of Chinese fan was the palm leaf fan pukuishan (Chinese: 蒲葵扇), also known as pushan (Chinese: 蒲扇), which was made of the leaves and stalks of pukui (Livistona chinensis).[11]

Zheshan

[edit]The folding fan (Chinese: 折扇), invented in Japan, was later introduced to the Chinese in the 10th century.[12][6]: 12 In 988 AD, folding fans were first introduced in China by a Japanese monk from Japan as a tribute during the Northern Song dynasty; these folding fans became very fashionable in China by the Southern Song dynasty.[9]: 8, 12–16 The folding fans were referred to as "Japanese fans" by the Chinese.[6]: 15 While the folding fans gained popularity, the traditional silk round fans continued to remain mainstream in the Song dynasty.[6]: 16 The folding fan later became very fashionable in the Ming dynasty;[5] however, folding fans were met with resistance because they were believed to be intended for the lower-class people and servants.[6]: 17

The Chinese also innovated the design of the folding fan by creating the brisé fan ('broken fan').[13]: 161

- Chinese hand fans

-

Folding fan with a Chinese painting and a Chinese poem, painted by the Qianlong emperor for his mother Empress Dowager Xiaoshengxian, Qing dynasty, 1762 AD

-

Chinese folding fans used in the performance of Kung Fu

-

Brisé fan, a typical commercially produced scented wood folding fan; this one features a painting of the Great Wall of China

-

Chinese folding fan, early 1600s, Spain

Foreign export

[edit]From the late 18th century until 1845, trade between America and China flourished. During this period, Chinese fans reached the peak of their popularity in America; popular fans among American women were the brisé fan, and fans made of palm leaf, feather, and paper.[14]: 84 The most popular type during this period appeared to have been the palm leaf fan.[14]: 84 The custom of using fans among the American middle class and by ladies was attributed to this Chinese influence.[14]: 84

Japan

[edit]In ancient Japan, hand fans, such as oval and silk fans, were greatly influenced by Chinese fans.[15] The earliest visual depiction of fans in Japan dates back to the 6th century AD, with burial tomb paintings showed drawings of fans. The folding fan was invented in Japan,[16] with dates ranging from the 6th to 9th centuries;[17][18][19][20] it was a court fan called the akomeogi (衵扇), after the court women's dress named akome.[17][21] According to the Song Sui (History of Song), a Japanese monk Chōnen (ja:ちょう然/奝然, 938-1016) offered the folding fans (twenty wooden-bladed fans (桧扇, hiōgi) and two paper fans (蝙蝠扇, kawahori-ogi) to the emperor of China in 988.[19][20][22]

Later in the 11th century, Korean envoys brought along Korean folding fans which were of Japanese origin as gifts to Chinese court.[23] The popularity of folding fans was such that sumptuary laws were passed during Heian period which restricted the decoration of both hiōgi and paper folding fans.[22][24]

-

Japanese rigid fan (uchiwa)

-

Japanese foldable fan (sensu)

-

Japanese foldable fan of late Heian period (12th century)

-

Noh performance at Itsukushima Shrine

The earliest fans in Japan were made by tying thin stripes of hinoki (or Japanese cypress) together with thread. The number of strips of wood differed according to the person's rank. Later in the 16th century, Portuguese traders introduced it to the west and soon both men and women throughout the continent adopted it.[18] They are used today by Shinto priests in formal costume and in the formal costume of the Japanese court (they can be seen used by the Emperor and Empress during enthronement and marriage) and are brightly painted with long tassels. Simple Japanese paper fans are sometimes known as harisen.

Printed fan leaves and painted fans are done on a paper ground. The paper was originally handmade and displayed the characteristic watermarks. Machine-made paper fans, introduced in the 19th century, are smoother, with an even texture. Even today, geisha and maiko use folding fans in their fan dances as well.

Japanese fans are made of paper on a bamboo frame, usually with a design painted on them. In addition to folding fans (ōgi),[25] the non-bending fans (uchiwa) are popular and commonplace.[26] The fan is primarily used for fanning oneself in hot weather. The uchiwa fan subsequently spread to other parts of Asia, including Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, and such fans are still used by Buddhist monks as "ceremonial fans".[27]

Fans were also used in the military as a way of sending signals on the field of battle. However, fans were mainly used for social and court activities. In Japan, fans were variously used by warriors as a form of weapon, by actors and dancers for performances, and by children as a toy.

Traditionally, the rigid fan (also called fixed fan) was the most popular form in China,[28] although the folding fan came into popularity during the Ming dynasty between the years of 1368 and 1644, and there are many beautiful examples of these folding fans still remaining.[29]

The mai ogi (or Japanese dancing fan) has ten sticks and a thick paper mount showing the family crest, and Japanese painters made a large variety of designs and patterns. The slats, of ivory, bone, mica, mother of pearl, sandalwood, or tortoise shell, were carved and covered with paper or fabric. Folding fans have "montures" which are the sticks and guards, and the leaves were usually painted by craftsmen. Social significance was attached to the fan in the Far East as well, and the management of the fan became a highly regarded feminine art. Fans were even used as a weapon – called the iron fan, or tessen in Japanese.

See also, the gunbai, a military leader's fan (in old Japan); used in the modern day as an umpire's fan in sumo wrestling, it is a type of Japanese war fan, like the tessen.

Korea

[edit]Every Dano (May 5 of the lunar calendar)[when?] when the heat began, there was a custom in which the king distributed hand fans to his vassals. The vassal, who received a hand fan from the king, did an ink-and-wash painting and handed out white fans to his elders and the indebted people, which has made the practice of exchanging hand fans widely popular. These cultural factors also contributed to the creation of various types of hand fan in Korea.

-

A Korean man holding hand fan

-

Korean fan dance, Buchaechum

-

Pearls hand fan, Jinjuseon

-

Pansori performance

-

Tightrope walking, Jultagi

-

Traditional dance, Hallyangmu

Vietnam

[edit]The hand fan (Quạt tay) is an integral part of Vietnamese culture. According to the Vân Đài Loại Ngữ, a book written by Lê Quý Ðôn, in the old times Vietnamese people used hand fans made from bird feather and quạt bồ quỳ, a type of fan made from leaves of the taraw palm tree. The folding fans only started appearing in Vietnam in the 10th century, known as quạt tập diệp in Vietnamese. Christian missionary Christoforo Borri recorded that in 1621, both Vietnamese men and women frequently held hand fans as part of their daily garment.

Many villages in Vietnam have long-dating traditions of making exquisite hand fans such as Canh Hoạch village and Đào Xá village, with fan-making dating back to the early 19th century.

Simple handheld fans, such as quạt mo and the quạt nan are commonly found in the Vietnamese countrysides and popularly used among farmers and working people. The Quạt mo has the simplest design, cut directly from the dried Areca leaf stems, then pressed to flatten. It appears in "Thằng Bờm", a well-known Vietnamese ca dao (a type of Vietnamese folk song). The quạt nan also has a simple design, made by sewing a half-moon shaped Maclurochloa leaf onto a straight bamboo stick.

Re-introduction in Europe

[edit]

Hand fans were absent from Europe during the High Middle Ages until they were reintroduced in the 13th and 14th centuries. Fans from the Middle East were brought by Crusaders, and refugees from the Byzantine Empire.

In the 15th and early 16th century, Chinese folding fans were introduced in Europe and later played an important role in the social circles of Europe in the 18th century.[5][30]: 82 The Portuguese traders first opened up the sea route to China in the 15th century and reached Japan in the mid-16th century,[31]: 26 and appear to be the first people who introduced Oriental (Chinese and Japanese) fans in Europe which lead to their popularity, as well as the increased oriental fan imports in Europe.[5][32]: 251

The fan became especially popular in Spain, where flamenco dancers used the fan and extended its use to the nobility.

European fan-makers have introduced more modern designs and have enabled the hand fan to work with modern fashion.

17th century

[edit]

In the 17th century the folding fan, and its attendant semiotic culture, were introduced from China and Japan. By the end of the 17th century, there were enormous imports of China folding in Europe due to its popularity and to a lesser extent, Japanese folding fans were also reaching Europe by that period.[5]

These fans are particularly well displayed in the portraits of the high-born women of the era. Queen Elizabeth I of England can be seen to carry both folding fans decorated with pom poms on their guardsticks as well as the older style rigid fan, usually decorated with feathers and jewels. These rigid style fans often hung from the skirts of ladies, but of the fans of this era it is only the more exotic folding ones which have survived. Those folding fans of the 15th century found in museums today have either leather leaves with cut out designs forming a lace-like design or a more rigid leaf with inlays of more exotic materials like mica. One of the characteristics of these fans is the rather crude bone or ivory sticks and the way the leather leaves are often slotted onto the sticks rather than glued as with later folding fans. Fans made entirely of decorated sticks without a fan "leaf" were known as brisé fans. The brisé fan originated in China. However, despite the relative crude methods of construction, folding fans were at this era high status, exotic items on par with elaborate gloves as gifts to royalty.

In the 17th century the rigid fan which was seen in portraits of the previous century had fallen out of favour as folding fans gained dominance in Europe. Fans started to display well painted leaves, often with a religious or classical subject. The reverse side of these early fans also started to display elaborate flower designs. The sticks are often plain ivory or tortoiseshell, sometimes inlaid with gold or silver pique work. The way the sticks sit close to each other, often with little or no space between them is one of the distinguishing characteristics of fans of this era.

In 1685 the Edict of Nantes was revoked in France. This caused large scale immigration from France to the surrounding Protestant countries (such as England) of many fan craftsmen. This dispersion in skill is reflected in the growing quality of many fans from these non-French countries after this date.

18th century

[edit]In the 18th century, fans reached a high degree of artistry and were being made throughout Europe often by specialized craftsmen, either in leaves or sticks. Folded fans of silk, or parchment were decorated and painted by artists. Fans were also imported from China by the East India Companies at this time. Around the middle 18th century, inventors started designing mechanical fans. Wind-up fans (similar to wind-up clocks) were popular in the 18th century.

19th century

[edit]In the 19th century in the West, European fashion caused fan decoration and size to vary.

It has been said that in the courts of England, Spain and elsewhere, fans were used in a more or less secret, unspoken code of messages.[34] These fan languages were a way to cope with the restricting social etiquette. However, modern research has proved that this was a marketing ploy developed in the 19th century[35] – one that has kept its appeal remarkably over the succeeding centuries. This is now used for marketing by fan makers like Cussons & Sons & Co. Ltd who produced a series of advertisements in 1954 showing "the language of the fan" with fans supplied by the well known French fan maker Duvelleroy.[citation needed]

The rigid or screen fan (éventail a écran) became also fashionable during the 18th and 19th century. They never reached the same level of popularity as the easy to carry around, folding fans which became almost an integrated part of women's dress. The screen fan was mainly used inside the interior of the house. In 18th and 19th century paintings of interiors one sometimes sees one laying on a chimney mantle. They were mainly used to protect a woman's face against the glare and heat of the fire, to avoid getting "coup rose", or ruddy cheeks from the heat. But probably not in the least it served to keep the heat from spoiling the carefully applied make-up which in those days was often wax-based. Until the 20th century houses were heated by open fires in chimneys or by stoves, and the lack of insulation made many a house very draughty and cold during winter. Therefore, any social or family gathering would be in close proximity to the fireplace.

The design of the screen fan is a fixed handle, most often made out of exquisitely turned (painted or guided) wood, fixed to a flat screen. The screen could be made out of silk stretched on a frame or thin wood, leather or papier mache. The surface is often exquisitely painted with scenes ranging from flowers and birds of paradise to religious scenes. At the end of the 19th century they disappeared when the need for them ceased to exist. During the 19th century names like the Birmingham-based firm of Jennens and Bettridge produced many papier-mâché fans.

Modern day

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2020) |

Modern day hand fans are less popular than in the past, but are still used by many.

Drag subculture

[edit]A large group that continues to use folding hand fans for cultural and fashion use are drag queens. Stemming from ideas of imitating and appropriating cultural ideas of excess, wealth, status and elegance, large folding hand fans, sometimes 12 inches (30 cm) or more in radius, are used to punctuate speech, as part of performances, or as accessories to an outfit. Fans may have phrases taken from the lexicon of drag and LGBTQ+ culture written on them, and may be decorated in other ways, such as the addition of sequins or tassels.

Folding fans are often used to emphasize a point in a person's speech, rather than for express use of fanning oneself. A person might harshly snap open the fan when engaging in "throwing shade" on (comically insulting) another person, creating a loud snapping noise that punctuates the insult. Drag dance numbers also utilise larger hand fans as a way to add flair and as a prop, used to emphasise movements in the dance.

Popular drag comedy webshow UNHhhh has used folding fans as a point of humour, with the sound made by a folding fan unfolding coined onomatopoeically as a "thworp" by the editors.

Categories

[edit]Hand fans have three general categories:

- Fixed (or rigid, flat) fans (Chinese: 平扇, píng shàn; Japanese: 団扇, uchiwa): circular fans, palm-leaf fans, straw fans, feather fans

- Folding fans (Chinese: 折扇, zhé shàn; Japanese: 扇子, sensu): silk folding fans, paper folding fans, sandalwood fans

- Modern powered mechanical hand fans: hand fans which appear as mini mechanical rotating fans with blades. These are usually axial fans, and often use blades made from a soft material for safety. These are usually battery operated, but can be hand cranked as well.

Gallery

[edit]-

Japanese foldable fan, painted by Hokusai

-

Japanese kamon

-

Bengalese fans used in India

-

American fan from Index of American Design, National Gallery of Art

-

Vietnamese woven palm leaf fan

-

Hand fan crafted from leather from southern Thailand

-

Very old ornamental fan from Sri Lanka

-

A homemade hand fan made with paper

See also

[edit]- Church fan – Fans used in churches in the United States

Use in fashion

[edit]Use in dance

[edit]- Buchaechum – Korean fan dance

- Cariñosa – national dance of the Philippines

- Singkil – traditional Maranao dance from the Philippines

- Pagapir – a traditional fan dance in Mindanao, Philippines

- Nihon-buyō – traditional dance originating from Japan

Use as weapons

[edit]Use in comedy

[edit]Use in politics

[edit]- Islami Andolan Bangladesh – an Islamic political party in Bangladesh that uses a hand fan as its electoral symbol

Museums

[edit]- Musée de l'Éventail (Paris)

- The Fan Museum in Greenwich (Greenwich, London)

- The Hand Fan Museum in Healdsburg, California

References

[edit]- ^ "Online Exhibit - A Brief History of the Hand Fan". web.ics.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2021-09-26.

- ^ a b c A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Flabellum

- ^ ῥιπίς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ "Art of Chinese Fans". en.chinaculture.org. p. 1. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chinese Fans | Chinese Art Gallery | China Online Museum". www.chinaonlinemuseum.com. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Qian, Gonglin (2004). Chinese fans: artistry and aesthetics. San Francisco: Long River Press. ISBN 978-1-59265-020-0. OCLC 867778328.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Chinese Fan — History, Tradition, and Culture | ChinaFetching". ChinaFetching.com. Retrieved 2022-08-19.

- ^ "Chinese Hand Fans". hand-fan.org. Archived from the original on 2019-02-02. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- ^ a b c d e f g Qian, Gonglin (2004). Chinese fans: artistry and aesthetics (1st ed.). San Francisco: Long River Press. ISBN 1-59265-020-1. OCLC 52979000.

- ^ "articles - brief history of fans". aboutdecorativestyle.com.

- ^ a b "A Brief Introduction to Hanfu's Fans Culture - 2021". www.newhanfu.com. 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- ^ Panati, Charles (2016). Panati's extraordinary origins of everyday things. Book Sales. ISBN 978-0-7858-3437-3. OCLC 962329974.

- ^ Yarwood, Doreen (2011). Illustrated encyclopedia of world costume. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-43380-6. OCLC 678535823.

- ^ a b c Davis, Nancy E. (2019). The Chinese lady: Afong Moy in early America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-093727-0. OCLC 1089978299.

- ^ "Japanese Hand Fans". hand-fan.org. Archived from the original on 2012-09-07. Retrieved 2012-06-28.

- ^ Nathan, Richard (17 April 2020). "The First Portable Device Loved by Japan's Literati". Red Circle Authors. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ a b Halsey, William Darrach; Friedman, Emanuel (1983). Collier's encyclopedia: with bibliography and index. Vol. 9. Macmillan Educational Co. p. 556.

In the 7th century the folding fan evolved, the earliest form of which was a court fan called the "Akomeogi", which had thirty-eight blades connected by a rivet; it had artificial flowers at the corners and twelve long, colored silk streamers.

- ^ a b Lipinski, Edward R. (1999). The New York Times home repair almanac: a season-by-season guide for maintaining your home. Lebhar-Friedman Books. ISBN 0-86730-759-5.

The Japanese developed the folding fan, the Akomeogi, during the sixth century. Portuguese traders introduced it to the west in the 16th century and soon both men and women throughout the continent adopted it.

- ^ a b Qian, Gonglin (2000). Chinese fans: artistry and aesthetics. Long River Press. p. 12. ISBN 1-59265-020-1.

The first folding fan arrived as a tribute that was brought to China by a Japanese monk in 988. Writings of both Japanese and Chinese scholars concerning the folding fan, which was believed to have been first invented in Japan, apparently suggest that it received its shape from the design of a bat's wing.

- ^ a b Verschuer, Charlotte von (2006). Across the perilous sea: Japanese trade with China and Korea from the seventh to the sixteenth centuries. Cornell University. p. 72. ISBN 1-933947-03-9.

Another Japanese creation enjoyed great success among foreigners: the folding fans. It was invented in Japan in the eighth or ninth century, when only round and fixed (uchiwa) fans made of palm leaves were known. -- their usage had spread throughout China in antiquity. Two types of folding fans developed: one was made of cypress-wood blades bound by a thread (hiogi); the other had a frame with fewer blades which was covered in Japanese paper and folded in a zigzag patterns (kawahori-ogi).

"The paper fan was described by a thirteenth-century Chinese author, but well before that date Chōnen had offered twenty wooden-bladed fans and two paper fans to the emperor of China." - ^ 衵扇 [Akomeogi] (in Japanese). Mypedia.

- ^ a b Hutt, Julia; Alexander, Hélène (1992). Ōgi: a history of the Japanese fan. Dauphin Pub. p. 14. ISBN 1-872357-08-3.

It was recorded in the Song Shu [sic.: the Song Sui is the correct source], the official history of the Chinese Song dynasty (960-1279), that in 988 a Japanese monk, Chonen, presented at court gifts of...

"There are also numerous references to folding fans in the great classical literature of the Heian period (794-1185), in particular the Genji Monogatari (The Tale of Genji) by Murasaki Shikibu and the Makura no Sōshi (The Pillow Book) by Sei Shōnagon. Already by the end of tenth century, the popularity of folding fans was such that sumptuary laws were promulgated during Chōho era (999-1003) which restricted the decoration of both hiogi and paper folding fans." - ^ Tsang, Ka Bo (2002). More than keeping cool: Chinese fans and fan painting. Royal Ontario Museum. p. 10. ISBN 0-88854-439-1.

Guo Ruoxu, for example, has included a short note about the folding fan in his Tuhua Jian Wen Zhi (Records of Paintings Seen and Heard About, 1074) It states that Korean envoys often brought along Korean folding fans as gifts. They were, Guo also pointed out, of Japanese origin.

- ^ Medley, Margaret (1976). Chinese painting and the decorative style. University of London School of Oriental and African Studies, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art. p. 106. ISBN 0-7286-0028-5.

In origin it was evidently Japanese, common already in the Heian period. A fragment of a late Heian folding-fan was excavated some decade ago at Takao-yama. Japanese fans were well known in China during the late eleventh century.

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric et al. (2005). "Ōgi" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 738., p. 738, at Google Books

- ^ Nussbaum, "Uchiwa", p. 1006., p. 1006, at Google Books

- ^ "Buddhist Monks Ceremonial Fans". Thebuddhasface.co.uk. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ "fan - decorative arts". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ ChinesePod Weekly, Chinese Fans: More Than Keeping Cool Archived 2012-11-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wallis, Wilson D. (2003). Kenneth Thompson (ed.). Culture and progress. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-47940-3. OCLC 857599674.

- ^ Behnke, Alison (2003). Japan in pictures. Minneapolis, MN.: Lerner Publications Co. ISBN 0-8225-1956-9. OCLC 46991889.

- ^ Baghdiantz McCabe, Ina (2008). Orientalism in early modern France: Eurasian trade, exoticism, and the Ancien Régime. Berg. ISBN 978-1-84788-463-3. OCLC 423067636.

- ^ Lazatin, Hannah (28 May 2018). "The Secret Messages Filipinas Used to Send With Their Abanikos". Esquire. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Indecent Fan Proposals - A Nice Gesture by Jeroen Arendsen". jeroenarendsen.nl. 19 June 2006.

- ^ FANA Journal, spring 2004, Fact & Fiction about the language of the fan by J.P. Ryan

Sources

[edit]- Nussbaum, Louis Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 48943301

Books

[edit]- Alexander, Helene. The Fan Museum, Third Millennium Publishing, 2001 ISBN 0-9540319-1-1

- Alexander, Helene & Hovinga-Van Eijsden, Fransje. A Touch of Dutch - Fans from the Royal House of Orange-Nassau, The Fan Museum, February 2008, ISBN 0-9540319-5-4

- Armstrong, Nancy. Book of Fans. Smithmark Publishing, 1984. ISBN 0-8317-0952-9

- Armstrong, Nancy. Fans, Souvenir Press, 1984 ISBN 0-285-62591-8

- Bennett, Anna G. Unfolding beauty: The art of the fan : the collection of Esther Oldham and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Thames and Hudson (1988). ISBN 0-87846-279-1

- Bennett, Anna G. & Berson, Ruth Fans in fashion. Publisher Charles E. Tuttle Co. Inc & The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (1981) ISBN 0-88401-037-6

- Biger, Pierre-Henri. Sens et sujets de l'éventail européen de Louis XIV à Louis-Philippe. Histoire of Art Thesis, Rennes 2 University, 2015. (https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01220297)

- Checcoli, Anna. " Il ventaglio e i suoi segreti ", Tassinari, 2009

- Checcoli, Anna. " Ventagli Cinesi Giapponesi ed Orientali ", Tassinari, 2009

- Cowen, Pamela. A Fanfare for the Sun King: Unfolding Fans for Louis XIV, Third Millennium Publishing (September, 2003) ISBN 1-903942-20-9

- Das, Justin. Pankha -Traditional crafted hand fans of the Indian Subcontinent from the collection of Justin Das - The fan museum, Greenwich (2004)

- Faulkner, Rupert. Hiroshige Fan Prints, V&A publications, 2001 ISBN 1-85177-332-0

- Fendel, Cynthia. Novelty Hand Fans, Fashionable Functional Fun Accessories of the Past. Hand Fan Productions, 2006 ISBN 978-0-9708852-1-0

- Fendel, Cynthia. Celluloid Hand Fans. Hand Fan Productions, 2001. ISBN 0-9708852-0-2

- Gitter, Kurt A. Japanese fan paintings from western collections. Publisher - New Orleans Museum of Art (1985). ISBN 0-89494-021-X

- Hart, Avril & Taylor, Emma. Fans (V & A Fashion Accessories Series). Publisher- V & A Publications. ISBN 1-85177-213-8

- Hutt, Julia & Alexander, Helene. Ogi: A History of the Japanese Fan. Art Media Resources; Bilingual edition (February 1, 1992) ISBN 1-872357-08-3

- Irons, Neville John. Fans of Imperial China. Kaiserreich Kunst Ltd, 1982 ISBN 0-907918-00-X

- Letourmy-Bordier, Georgina & Le Guen, Sylvain, L'éventail, matières d'excellence : La nature sublimée par les mains de l'artisan, Musée de la Nacre et de la Tabletterie (September 2015) ISBN 978-2-9531106-9-2

- Mayor, Susan. A Collectors Guide to Fans, Charles Letts, 1990

- Mayor, Susan. The Letts Guide to Collecting Fans. Charles Letts, 1991 ISBN 1-85238-128-0

- North, Audrey. Australia's fan heritage. Boolarong Publications (1985). ISBN 0-86439-001-7

- Qian, Gonglin. Chinese Fans: Artistry and Aesthetics (Arts of China, #2). Long River Press (August 31, 2004) ISBN 1-59265-020-1

- Rhead, G. Wooliscroft. The History of the Fan, Kegan Paul, 1910

- Roberts, Jane. Unfolding Pictures: Fans in the Royal Collection. Publisher - Royal Collection (January 30, 2006. ISBN 1-902163-16-8

- Tam, C.S. Fan Paintings by Late Ch'ing Shanghai Masters. Publisher - Urban Council for an exhibition in the Hong Kong Museum of Art (1977)

- Vannotti, Franco. Peinture Chinoise de la Dynastie Ts'ing (1644–1912). Collections Baur, Geneve (1974)

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Hand fans at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hand fans at Wikimedia Commons

- A visual guide to Victorian fan language, photos by Fabio and Gabrielle Arciniegas

- mm's fan collection with monographies on love symbols on fans, celluloid fans, George Barbier and more

- Hand fan collection Anna Checcoli

- All About Hand Fans with Cynthia Fendel

- Hand Fan Museum

- The Fan Circle International

- Tessen warrior fan Archived 2013-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- The Fan Museum in Greenwich, London

- Fan Association of North America

- Fans in the Staten Island Historical Society Online Collections Database

- La Place de l'Eventail (French website dedicated to the European Hand Fan (most pages in English)

- Galerie Le Curieux, Paris

- Fans in the 16th and 17th Centuries

- Variety of Hand Held fans in different colour and styles

- Maison Sylvain Le Guen - contemporary hand fans by Sylvain Le Guen Archived 2021-09-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Allhandfans - Site entirely dedicated to the hand fan Archived 2020-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Museu Tèxtil i d'Indumentària in Barcelona

![Japanese rigid fan (uchiwa [ja])](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Uchiwa.jpg/121px-Uchiwa.jpg)