Coit v. Green

| Coit v. Green | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued December 9, 1971 Reargued December 8, 1971 Decided December 20, 1971 | |

| Full case name | Coit v. Green |

| Citations | 404 U.S. 997 (more) 92 S. Ct. 564; 30 L. Ed. 2d 550 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for plaintiffs, Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971) |

| Subsequent | Judgment explained in Bob Jones University v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725, 740, n. 11, 94 S.Ct. 2038, 2047, 40 L.Ed.2d 496 (1974), that this affirmance lacks precedential weight because no controversy remained in Green by the time the case reached this Court. |

| Holding | |

| Using federal tax funds to finance private schools for purposes of segregation of students in segregation academies violates the IRS public tax fund rules, as well as the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, because discrimination coupled with segregation is inherently unequal. District of Columbia district court affirmed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

| Majority | Burger, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| Section 501(c)(3) of IRC | |

Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court affirmed a decision that a private school which practiced racial discrimination could not be eligible for a tax exemption.[1]

Summary of findings

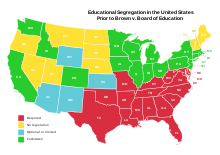

[edit]The case resulted in a legal challenge to a group of segregation academies in Holmes County, Mississippi, which had formed after the local school district had integrated. In May 1969, a group of African American parents of students in the Holmes County public schools sued the Treasury Department to prevent three new Whites-only schools from receiving tax exemption. A preliminary injunction was issued in the case, known at the time as Green v. Kennedy, in January 1970. Later that year, President Richard Nixon ordered the Internal Revenue Service to enact a new policy denying tax exemptions to private schools that practiced racial discrimination.[2][3] In Green v. Connally,[4][5] the court declared that neither IRC 501(c)(3) nor IRC 170 provided for tax-exempt status or deductible contributions to any organization operating a private school that discriminates in admissions on the basis of race. Since this time, if a school has adopted and announced a racially non-discriminatory admissions policy and has not taken any overt action to discriminate in admissions, the Service concludes that the school has a racially non-discriminatory admissions policy. The U.S. Supreme Court, however, specifically did not rule on the hypothetical possibility of a school which discriminated against minorities for religious reasons.

In the interim, the IRS took steps to implement the nondiscrimination requirement including Revenue Ruling 71–447, 1971–2 C.B. 230, Revenue Procedure 72–54, 1972–2 C.B. 834, Revenue Procedure 75–50, 1975–2 C.B. 587, and Revenue Ruling 75–231, 1975–1 C.B. 158. Without comment, the Supreme Court affirmed the judgment of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia at the end of 1971 for the families in this case.

Results

[edit]

A decade later, scores of schools had not changed policies and remained ineligible for tax-exempt status.[6]

The court case, along with its predecessor Green v. Connally, played a major role in mobilizing the movement that became the Christian right. Many of the segregation academies targeted under this ruling were church sponsored, which caught the attention of a number of evangelical Christian leaders. Conservative operative Paul Weyrich sought to use the enforcement of the ruling by the IRS as a wedge issue to mobilize evangelical leaders into political activism, and reframed the issue as government intrusion and attacks on religious freedom, effectively diverting attention from the racial aspect.[2][7][3] The largest institution which was targeted under the ruling was fundamentalist Christian college Bob Jones University, which lost its tax exemption in 1976 for its policy prohibiting interracial dating.[8][9] The IRS struggled to implement enforcement of the ruling throughout the 1970s, however, and in 1978 proposed a new policy which would have revoked the tax exemption of private schools based on their racial composition relative to the demographics of their communities. This proposal never went into effect, but drew furious backlash from religious conservatives, and played a major role in turning them against then-President Jimmy Carter.[10][11]

See also

[edit]- United States Supreme Court cases during the Burger Court

- Runyon v. McCrary

- Bob Jones University v. United States

References

[edit]- ^ See Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127 (D.D.C. 1970), later decision reported sub nom. Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971), summarily aff'd sub nom (African-Americans "need not be required to plead and show that, in the absence of illegal governmental encouragement, private institutions would not "elect to forgo 'favorable tax treatment, and that this will' result in the availability to complainants of services previously denied"); McGlotten v. Connally, 338 F. Supp. 448 (D.D.C. 1972); Pitts v. Wisconsin Dept. of Revenue, 333 F. Supp. 662 (E.D. Wis.1971) ("As perusal of these reported decisions reveals, the lower courts have not assumed that such allegations and proofs were somehow required by Article Three of the United States Constitution"); Simon v. Eastern Kentucky Welf. Rights. Org., 426 U.S. 26, 64 (1976).

- ^ a b Balmer, Randall (August 10, 2021). Bad Faith: Race and the Rise of the Religious Right. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9781467462907 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Balmer, Randall (September 24, 2021). "The Historian's Pickaxe: Uncovering the Racist Origins of the Religious Right" (PDF). The Andrea Mitchell Center for the Study of Democracy. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- ^ Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971), aff'd sub nom, Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971).

- ^ "The Real Origins of the Religious Right". POLITICO Magazine. May 27, 2014.

- ^ TAYLOR Jr, STUART (January 12, 1982). "EX-TAX OFFICIALS ASSAIL SHIFT ON SCHOOL EXEMPTION STATUS". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ Balmer, Randall (December 29, 2024). "Jimmy Carter: The Last Progressive Evangelical". Politico. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- ^ Linda Wertheimer (June 23, 2006). "Evangelical: Religious Right Has Distorted the Faith". NPR. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Perry, Samuel L.; Braunstein, Ruth; Gorski, Philip S.; Grubbs, Joshua B. (March 2022). "Historical Fundamentalism? Christian Nationalism and Ignorance About Religion in American Political History". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 61 (1): 24. doi:10.1111/jssr.12760. ISSN 0021-8294.

- ^ Martin, William Curtis (1996). With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America. New York City: Broadway Books. p. 173. ISBN 9780553067491. Retrieved January 8, 2025 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lehmann, Chris (December 30, 2024). "How Jimmy Carter Lost Evangelical Christians to the Right". The Nation. Retrieved January 8, 2025.

- Doe and Rabago v. Kamehameha Schools/Bernice Pauahi Bishop Estate, et al. (2007).

- IRS (1982). Update on Private Schools.

- Goluboff, R. L. (2000). "The Thirteenth Amendment and the Lost Origins of Civil Rights." Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Duke Law Journal, 50 Paper was presented at the 2000 Annual Meeting of the American Society for Legal History. p. 1609.