Steve Martin

| Steve Martin | |

|---|---|

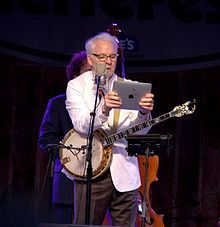

Martin in 2017 | |

| Birth name | Stephen Glenn Martin |

| Born | August 14, 1945 Waco, Texas, U.S. |

| Medium | |

| Education | |

| Years active | 1966–present |

| Genres | |

| Subject(s) | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 1 |

| Signature |  |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Labels | |

| Website | stevemartin |

Stephen Glenn Martin (born August 14, 1945) is an American comedian, actor, writer, producer, and musician. Known for his work in comedy films, television, and recording, he has received many accolades, including five Grammy Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award and an Honorary Academy Award,[1] in addition to nominations for two Tony Awards. He also received the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in 2005, the Kennedy Center Honors in 2007, and an AFI Life Achievement Award in 2015. In 2004, Comedy Central ranked Martin at sixth place in a list of the 100 greatest stand-up comics.[2] The Guardian named him one of the best actors never to have received an Academy Award nomination.[3]

Martin first came to public notice as a writer for The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, for which he won a Primetime Emmy Award in 1969, and later as a frequent host on Saturday Night Live. He became one of the most popular U.S. stand-up comedians during the 1970s, performing his brand of offbeat, absurdist comedy routines before sold-out theaters on national tours. He then starred in films such as The Jerk (1979), Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid (1982), The Man with Two Brains (1983), All of Me (1984), ¡Three Amigos! (1986), Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987), Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (1988), L.A. Story (1991), Bowfinger (1999) and Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003). He played family patriarchs in Parenthood (1989), the Father of the Bride films (1991–1995), Bringing Down the House (2003), and the Cheaper by the Dozen films (2003–2005).

Since 2015, Martin has embarked on several national comedy tours with fellow comedian Martin Short.[4] In 2018, they released their Netflix special An Evening You Will Forget for the Rest of Your Life which received four Primetime Emmy Award nominations. In 2021, he co-created and starred in his first television show, the Hulu comedy series Only Murders in the Building, alongside Short and Selena Gomez, for which he earned three Primetime Emmy Award nominations, two Screen Actors Guild Award nominations, a Golden Globe Award nomination, and a 2021 Peabody Award nomination. In 2022, Martin and Short co-hosted Saturday Night Live together with Gomez making an appearance.

Martin is also known for writing the books to the musical Bright Star (2016) and to the comedy Meteor Shower (2017), both of which premiered on Broadway; he co-wrote the music to the former. He has played banjo since an early age and has included music in his comedy routines from the beginning of his professional career. He has released several music albums and has performed with various bluegrass acts, including Earl Scruggs. He has won three Grammy Awards for his music.[5]

Early life and education

[edit]

Stephen Glenn Martin was born on August 14, 1945,[6][7] in Waco, Texas,[8] the son of Mary Lee (née Stewart; 1913–2002) and Glenn Vernon Martin (1914–1997), a real estate salesman and aspiring actor.[9][10] He has an older sister, Melinda.[11]

Martin is of English, Scottish, Welsh, Scots-Irish, German, and French descent and grew up in Inglewood, California, with his sister and then later in Garden Grove, California, in a Baptist family.[12] Steve was a cheerleader at Garden Grove High School.[13] One of his earliest memories is seeing his father, as an extra serving drinks onstage at the Callboard Theater on Melrose Place in West Hollywood, California. During World War II, in the United Kingdom, his father appeared in a production of Our Town with Raymond Massey. Expressing his affection through gifts like cars and bikes, Steve's father was stern and not emotionally open to his son.[14] He was proud but critical, with Steve later recalling that in his teens his feelings for his father were mostly of hatred.[15]

Steve Martin's first job was at Disneyland, selling guidebooks on weekends and full-time during his school's summer break. The work lasted for three years (1955–1958). During his free time, he frequented the Main Street Magic shop, where tricks were demonstrated to patrons.[14] While working at Disneyland, he was captured in the background of the home movie that was made into the short-subject film Disneyland Dream, incidentally becoming his first film appearance. By 1960, he had mastered several magic tricks and illusions and took a paying job at the Magic shop in Fantasyland in August. There he perfected his talents for magic, juggling, and creating balloon animals in the manner of mentor Wally Boag,[16] frequently performing for tips.[17]

In his authorized biography, close friend Morris Walker suggests that Martin could "be described most accurately as an agnostic ... he rarely went to church and was never involved in organized religion of his own volition".[18] In his early 20s, Martin dated Melissa Trumbo, daughter of novelist and screenwriter Dalton Trumbo.

After high school, Martin attended Santa Ana College, taking classes in drama and English poetry. In his free time, he teamed up with friend and Garden Grove High School classmate Kathy Westmoreland to participate in comedies and other productions at the Bird Cage Theatre. He joined a comedy troupe at Knott's Berry Farm.[14] Later, he met budding actress Stormie Sherk, and they developed comedy routines and became romantically involved. Sherk's influence caused Martin to apply to the California State University, Long Beach, for enrollment with a major in philosophy.[14] Sherk enrolled at UCLA, about an hour's drive north, and the distance eventually caused them to lead separate lives.[19]

Inspired by his philosophy classes, Martin considered becoming a professor instead of an actor-comedian. Being at college changed his life.

It changed what I believe and what I think about everything. I majored in philosophy. Something about non sequiturs appealed to me. In philosophy, I started studying logic, and they were talking about cause and effect, and you start to realize, 'Hey, there is no cause and effect! There is no logic! There is no anything!' Then it gets real easy to write this stuff because all you have to do is twist everything hard—you twist the punch line, you twist the non sequitur so hard away from the things that set it up.[20]

Martin recalls reading a treatise on comedy that led him to think:

What if there were no punch lines? What if there were no indicators? What if I created tension and never released it? What if I headed for a climax, but all I delivered was an anticlimax? What would the audience do with all that tension? Theoretically, it would have to come out sometime. But if I kept denying them the formality of a punch line, the audience would eventually pick their own place to laugh, essentially out of desperation.[21]

Martin periodically spoofed his philosophy studies in his 1970s stand-up act, comparing philosophy with studying geology.

If you're studying geology, which is all facts, as soon as you get out of school you forget it all, but philosophy you remember just enough to screw you up for the rest of your life.[22]

In 1967, Martin transferred to UCLA and switched his major to theater. While attending college, he appeared in an episode of The Dating Game, winning a date with Deana Martin. Martin began working local clubs at night, to mixed notices, and at twenty-one, he dropped out of college.[23]

Career

[edit]Stand-up comedy

[edit]Late night

[edit]In 1967, his former girlfriend Nina Goldblatt, a dancer on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, helped Martin land a writing job with the show by submitting his work to head writer Mason Williams.[24] Williams initially paid Martin out of his own pocket. Along with the other writers for the show, Martin won an Emmy Award[25] in 1969 at the age of twenty-three.[14] He wrote for The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour and The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour. Martin's first television appearance was on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1968. He says:

[I] appeared on The Virginia Graham Show, circa 1970. I looked grotesque. I had a hairdo like a helmet, which I blow-dried to a puffy bouffant, for reasons I no longer understand. I wore a frock coat and a silk shirt, and my delivery was mannered, slow and self-aware. I had absolutely no authority. After reviewing the show, I was depressed for a week.[21]

During these years his roommates included Gary Mule Deer and Michael Johnson.[26] Gary Mule Deer supplied the first joke Martin submitted to Tommy Smothers for use on the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour show.[27] Martin opened for groups such as The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band (who returned the favor by appearing in his 1980 television special All Commercials), The Carpenters, and Toto. He appeared at The Boarding House, among other venues. He continued to write, earning an Emmy nomination for his work on Van Dyke and Company in 1976.

In the mid-1970s, Martin made frequent appearances as a stand-up comedian on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,[21] and on The Gong Show, HBO's On Location, The Muppet Show,[28] and NBC's Saturday Night Live (SNL). SNL's audience jumped by a million viewers when he made guest appearances, and he was one of the show's most successful hosts.[14] Martin has appeared on twenty-seven Saturday Night Live shows and guest-hosted sixteen times, second only to Alec Baldwin, who has hosted seventeen times as of February 2017[update]. On the show, Martin popularized the air quotes gesture.[29] While on the show, Martin grew close to several cast members, including Gilda Radner. On the night she died of ovarian cancer, a visibly shaken Martin hosted SNL and featured footage of himself and Radner together in a 1978 sketch.

Comedy albums

[edit]

In the 1970s, his television appearances led to the release of comedy albums that went platinum.[14] The track "Excuse Me" on his first album, Let's Get Small (1977), helped establish a national catch phrase.[14] His next album, A Wild and Crazy Guy (1978), was an even bigger success, reaching the No. 2 spot on the U.S. sales chart, selling over a million copies. "Just a wild and crazy guy" became another of Martin's known catchphrases.[14] The album featured a character based on a series of Saturday Night Live sketches in which Martin and Dan Aykroyd played the Festrunk Brothers; Yortuk and Georgi were bumbling Czechoslovak would-be playboys. The album ends with the song "King Tut", written and sung by Martin and backed by the "Toot Uncommons", members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. It was later released as a single, reaching No. 17 on the U.S. charts in 1978 and selling over a million copies.[14][30] The song came out during the King Tut craze that accompanied the popular traveling exhibit of the Egyptian king's tomb artifacts. Both albums won Grammys for Best Comedy Recording in 1977 and 1978, respectively. Martin performed "King Tut" on the April 22, 1978, SNL program.

Decades later, in 2012, The A.V. Club described Martin's unique style and its effect on audiences:

[Martin was] both a consummate entertainer and a glib, knowing parody of a consummate entertainer. He was at once a hammy populist with an uncanny, unprecedented feel for the tastes of a mass audience and a sly intellectual whose goofy shtick cunningly deconstructed stand-up comedy.[31]

On his comedy albums, Martin's stand-up is self-referential and sometimes self-mocking. It mixes philosophical riffs with sudden spurts of "happy feet", banjo playing with balloon depictions of concepts like venereal disease, and the "controversial" kitten juggling (he is a master juggler; the "kittens" were stuffed animal toys). His style is off-kilter and ironic and sometimes pokes fun at stand-up comedy traditions, such as Martin opening his act (from A Wild and Crazy Guy) by saying:

I think there's nothing better for a person to come up and do the same thing over and over for two weeks. This is what I enjoy, so I'm going to do the same thing over and over and over [...] I'm going to do the same joke over and over in the same show, it'll be like a new thing.

Or: "Hello, I'm Steve Martin, and I'll be out here in a minute."[29][32] In one comedy routine, used on the Comedy Is Not Pretty! album, Martin claimed that his real name was "Gern Blanston". The riff took on a life of its own. There is a Gern Blanston website, and for a time a rock band took the moniker as its name.[33]

Martin's show soon required full-sized stadiums for the audiences he was drawing. Concerned about his visibility in venues on such a scale, Martin began to wear a distinctive three-piece white suit that became a trademark for his act.[34] Martin stopped doing stand-up comedy in 1981 to concentrate on movies and did not return for thirty-five years.[14] About the decision, he said, "My act was conceptual. Once the concept was stated, and everybody understood it, it was done... It was about coming to the end of the road. There was no way to live on in that persona. I had to take that fabulous luck of not being remembered as that, exclusively. You know, I didn't announce that I was stopping. I just stopped."[35]

Return to standup

[edit]In 2016, Martin made a low-key comeback to live comedy, opening for Jerry Seinfeld. He performed a ten-minute stand-up routine before turning the stage over to Seinfeld.[36] Also in 2016 he staged a national tour with Martin Short and the Steep Canyon Rangers, which yielded a 2018 Netflix comedy special, Steve Martin and Martin Short: An Evening You Will Forget for the Rest of Your Life.[37] The special received four Primetime Emmy Award nominations with Martin receiving two nominations for Outstanding Writing for a Variety Special and Outstanding Music and Lyrics for "The Buddy Song".

Acting career

[edit]

1970s

[edit]By the end of the 1970s, Martin had acquired the kind of following normally reserved for rock stars, with his tour appearances typically occurring at sold-out arenas filled with tens of thousands of screaming fans. But unknown to his audience, stand-up comedy was "just an accident" for him; his real goal was to get into film.[20]

Martin had a small role in the 1972 film Another Nice Mess. In 1974, he starred in the Canadian travelogue production The Funnier Side Of Eastern Canada, created to promote tourism in Montreal and Toronto, which also included standup segments filmed at the Ice House in Pasadena, California.[38] His first substantial film appearance was in a short titled The Absent-Minded Waiter (1977). The seven-minute-long film, also featuring Buck Henry and Teri Garr, was written by and starred Martin. The film was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Short Film, Live Action. He made his first substantial feature film appearance in the musical Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, where he sang The Beatles' "Maxwell's Silver Hammer".

In 1979, Martin starred in the comedy film The Jerk, directed by Carl Reiner, and written by Martin, Michael Elias, and Carl Gottlieb. The film was a huge success, grossing over $100 million on a budget of approximately $4 million.[39]

Stanley Kubrick met with him to discuss the possibility of Martin starring in a screwball comedy version of Traumnovelle (Kubrick later changed his approach to the material, the result of which was 1999's Eyes Wide Shut). Martin was executive producer for Domestic Life, a prime-time television series starring friend Martin Mull, and a late-night series called Twilight Theater. It emboldened Martin to try his hand at his first serious film, Pennies from Heaven (1981), based on the 1978 BBC serial by Dennis Potter. He was anxious to perform in the movie because of his desire to avoid being typecast. To prepare for that film, Martin took acting lessons from director Herbert Ross and spent months learning how to tap dance. The film was a financial failure; Martin's comment at the time was "I don't know what to blame, other than it's me and not a comedy."[40]

1980s

[edit]Martin was in three more Reiner-directed comedies after The Jerk: Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid in 1982, The Man with Two Brains in 1983 and All of Me in 1984, his most critically acclaimed performance up to that point.[41][42][43] Martin was by now requesting almost $3 million per film, but Plaid and Two Brains both failed at the box office like Pennies, endangering his young career.[44] In 1986, Martin joined fellow Saturday Night Live veterans Martin Short and Chevy Chase in ¡Three Amigos!, directed by John Landis, and written by Martin, Lorne Michaels, and singer-songwriter Randy Newman. It was originally entitled The Three Caballeros and Martin was to be teamed with Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi. In 1986, Martin was in the movie musical film version of the hit Off-Broadway play Little Shop of Horrors (based on a famous B-movie), playing the sadistic dentist, Orin Scrivello. The film was the first of three films teaming Martin with Rick Moranis. In 1987, Martin joined comedian John Candy in the John Hughes movie Planes, Trains and Automobiles.[45] That same year, Martin starred in Roxanne, the film adaptation of Cyrano de Bergerac, which he co-wrote and won him a Writers Guild of America Award. It also garnered recognition from Hollywood and the public that he was more than a comedian. In 1988, he performed in the Frank Oz film Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, a remake of Bedtime Story, alongside Michael Caine. Also in 1988, he appeared at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater at Lincoln Center in a revival of Waiting for Godot directed by Mike Nichols.[46] He played Vladimir, with Robin Williams as Estragon and Bill Irwin as Lucky. Martin starred in the Ron Howard film Parenthood with Rick Moranis in 1989.

1990s

[edit]He later re-teamed with Moranis in the Mafia comedy My Blue Heaven (1990). In 1991, Martin starred in and wrote L.A. Story, a romantic comedy, in which the female lead was played by his then-wife Victoria Tennant. Martin also appeared in Lawrence Kasdan's Grand Canyon, in which he played the tightly wound Hollywood film producer, Davis, who was recovering from a traumatic robbery that left him injured, which was a more serious role for him. Martin also starred in a remake of the comedy Father of the Bride in 1991 (followed by a sequel in 1995) and in the 1992 comedy Housesitter, with Goldie Hawn and Dana Delany. In 1994, he starred in A Simple Twist of Fate; a film adaptation of Silas Marner.

In David Mamet's 1997 thriller The Spanish Prisoner, Martin played a darker role as a wealthy stranger who takes a suspicious interest in the work of a young businessman (Campbell Scott). In 1998, Martin guest starred with U2 in the 200th episode of The Simpsons titled "Trash of the Titans", providing the voice for sanitation commissioner Ray Patterson, and also voiced Hotep in the animated film The Prince of Egypt.

In 1999, Martin and Hawn starred in a remake of the 1970 Neil Simon comedy, The Out-of-Towners, and Martin went on to star with Eddie Murphy in the comedy Bowfinger, which he also wrote. He also appeared in Disney's Fantasia 2000 to introduce the segment Pines of Rome, along with Itzhak Perlman.

2000s

[edit]By 2003, Martin ranked fourth on the box office stars list, after starring in Bringing Down the House (2003) and Cheaper by the Dozen (2003), each of which earned over $130 million at U.S. theaters. That same year, he also played the villainous Mr. Chairman in the animation/live action blend, Looney Tunes: Back in Action. In 2005, Martin wrote and starred in Shopgirl, based on his own novella (2000), and starred in Cheaper by the Dozen 2. In 2006, he starred in the box office hit The Pink Panther, as the bumbling Inspector Clouseau. He reprised the role in 2009's The Pink Panther 2. When combined, the two films grossed over $230 million at the box office.

In the comedy Baby Mama (2008), starring Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, Martin played the founder of a health food company. Martin also appeared as a guest star in 30 Rock as Gavin Volure in the episode Gavin Volure. He was nominated for an Outstanding Guest Actor in a Comedy Series. The following year he starred in Nancy Meyers' romantic comedy It's Complicated (2009), opposite Meryl Streep and Alec Baldwin. In 2009, an article in The Guardian listed Martin as one of the best actors never to receive an Oscar nomination.[47]

2010s

[edit]

During the 2010s, Martin sparsely appeared in film and television. In 2011, he appeared with Jack Black, Owen Wilson, and JoBeth Williams in the birdwatching comedy The Big Year directed by David Frankel. The film was criticized for its lightweight story and was a box office bomb. After a three-year hiatus, Martin returned in 2015 when he voiced a role in the DreamWorks animated film Home alongside Jim Parsons and Rihanna. The film received mixed critical reception but was a financial success. In 2016, he played a supporting role in Ang Lee's war drama Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk. He also appeared as himself in Jerry Seinfeld's Netflix series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee in 2016. He also appeared in the taped version of Oh, Hello on Broadway (2017) as the guest. He also starred in the Netflix comedy special An Evening You Will Forget for the Rest of Your Life with Martin Short in 2018.

2020s

[edit]In 2020, Martin reprised his role as George Banks in the short Father of the Bride, Part 3(ish). Martin stars in and is an executive producer of Only Murders in the Building, a Hulu comedy series alongside Martin Short and Selena Gomez, which he created alongside John Hoffman.[48][49] In August 2022, Martin revealed that the series will likely be his final role, as he does not intend to seek out roles or cameos for other shows or films once the series ends.[50]

Writing

[edit]Books

[edit]Martin's first book was Cruel Shoes, a collection of comedic short stories and essays. It was published in 1979 by G. P. Putnam's Sons after a limited release of a truncated version in 1977.

Throughout the 1990s, Martin wrote various pieces for The New Yorker. In 2002, he adapted the Carl Sternheim play The Underpants, which ran Off Broadway at Classic Stage Company, and in 2008 co-wrote and produced Traitor, starring Don Cheadle. He has also written the novellas Shopgirl (2000) and The Pleasure of My Company (2003), both more wry in tone than raucous.[51] A story of a 28-year-old woman behind the glove counter at the Saks Fifth Avenue department store in Beverly Hills, Shopgirl was made into a film starring Martin and Claire Danes.[51] The film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2005 and was featured at the Chicago International Film Festival and the Austin Film Festival before going into limited release in the US. In 2007, he published a memoir, Born Standing Up, which Time magazine named as one of the Top 10 Nonfiction Books of 2007, ranking it at No. 6, and praising it as "a funny, moving, surprisingly frank memoir."[52] In 2010, he published the novel An Object of Beauty.[53]

Beginning in 2019, Martin has collaborated with cartoonist Harry Bliss as a writer for the syndicated single-panel comic Bliss.[54][55] Together, they published the cartoon collection A Wealth of Pigeons.[56] In 2022, they collaborated again for Martin's illustrated autobiography, Number One is Walking.[57]

Plays

[edit]

In 1993, Martin wrote his first full-length play, Picasso at the Lapin Agile. The first reading of the play took place in Beverly Hills, California at his home, with Tom Hanks reading the role of Pablo Picasso and Chris Sarandon reading the role of Albert Einstein. Following this, the play opened at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company in Chicago, and played from October 1993 to May 1994, then went on to run successfully in Los Angeles, New York City, and several other US cities.[58] In 2009, the school board in La Grande, Oregon, refused to allow the play to be performed after several parents complained about the content. In an open letter in the local Observer newspaper, Martin wrote:

I have heard that some in your community have characterized the play as 'people drinking in bars, and treating women as sex objects.' With apologies to William Shakespeare, this is like calling Hamlet a play about a castle [...] I will finance a non-profit, off-high school campus production [...] so that individuals, outside the jurisdiction of the school board but within the guarantees of freedom of expression provided by the Constitution of the United States can determine whether they will or will not see the play.[59]

Broadway

[edit]Inspired by Love has Come for You, Martin and Edie Brickell collaborated on his first musical, Bright Star. It is set in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina in 1945–46, with flashbacks to 1923. The musical debuted on Broadway on March 24, 2016.[60] Charles Isherwood of The New York Times praised its score by Martin and Brickell writing, "The shining achievement of the musical is its winsome country and bluegrass score, with music by Mr. Martin and Ms. Brickell, and lyrics by Ms. Brickell...the songs — yearning ballads and square-dance romps rich with fiddle, piano, and banjo, beautifully played by a nine-person band — provide a buoyancy that keeps the momentum from stalling."[61] The musical went on to receive five Tony Award nominations including Best Musical. Martin himself received Tony nominations for Best Book of a Musical and Best Original Score and received the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Music and the Outstanding Critics Circle Award for Best New Score. He also received a Grammy Award for Best Musical Theater Album.

Martin's next work as a playwright was the comic play Meteor Shower which opened at San Diego's Old Globe Theatre in August 2016,[62] and went on to Connecticut's Long Wharf Theatre later the same year.[63] The play opened on Broadway at the Booth Theater on November 29, 2017. The cast features Amy Schumer, Laura Benanti, Jeremy Shamos and Keegan-Michael Key, with direction by Jerry Zaks.[64][65] Critic Allison Adaot of Entertainment Weekly wrote, "Meteor Shower is a very funny play. Keening-like-a-howler-monkey funny. Design-a-new-cry-laughing-emoji funny...In the confident hands of writer and comedy maestro Steve Martin, the premise is polished to sparkling."[66]

Hosting

[edit]Martin hosted the Academy Awards solo in 2001 and 2003, and with Alec Baldwin in 2010.[67] In 2020, Martin opened the 92nd Academy Awards alongside Chris Rock with comedy material. They were not previously announced as that year's hosts, and joked after their opening monologue, "Well we've had a great time not hosting tonight".

In 2005, Martin co-hosted Disneyland: The First 50 Magical Years, marking the park's anniversary. Disney continued to run the show until March 2009, which now[when?] plays in the lobby of Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.

A fan of Monty Python, in 1989 Martin hosted the television special, Parrot Sketch Not Included – 20 Years of Monty Python.[68][69]

Music career

[edit]Banjo music

[edit]

Martin first picked up the banjo when he was around 17 years of age. Martin has stated in several interviews and in his memoir, Born Standing Up, that he used to take 33 rpm bluegrass records and slow them down to 16 rpm and tune his banjo down, so the notes would sound the same. Martin was able to pick out each note and perfect his playing.[citation needed] Martin learned how to play the banjo with help from John McEuen, who later joined the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. McEuen's brother later managed Martin as well as the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Martin did his stand-up routine opening for the band in the early 1970s. He had the band play on his hit song "King Tut", being credited as "The Toot Uncommons" (as in Tutankhamun).[citation needed] The banjo was a staple of Martin's 1970s stand-up career, and he periodically poked fun at his love for the instrument.[21] On the Comedy Is Not Pretty! album, he included an all-instrumental jam, titled "Drop Thumb Medley", and played the track on his 1979 concert tour. His final comedy album, The Steve Martin Brothers (1981), featured one side of Martin's typical stand-up material, with the other side featuring live performances of Steve playing banjo with a bluegrass band.

In 2001, he played banjo on Earl Scruggs's remake of "Foggy Mountain Breakdown". The recording was the winner of the Best Country Instrumental Performance category at the Grammy Awards of 2002. In 2008, Martin appeared with the band, In the Minds of the Living, during a show in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.[70] In 2009, Martin released his first all-music album, The Crow: New Songs for the 5-String Banjo with appearances from stars such as Dolly Parton.[71] The album won the Grammy Award for Best Bluegrass Album in 2010.[72] Nitty Gritty Dirt Band member John McEuen produced the album. Martin made his first appearance on The Grand Ole Opry on May 30, 2009.[73] In the American Idol season eight finals, he performed alongside Michael Sarver and Megan Joy in the song "Pretty Flowers". Martin is featured playing banjo on "I Hate Love" from Kelly Clarkson's tenth studio album Chemistry . It was released as a promotional single on June 2, 2023.[74]

Alison Brown co-wrote Foggy Morning Breaking[75] with Martin in 2023, and Wall Guitar in 2024.

Steep Canyon Rangers

[edit]

In June 2009, Martin played banjo along with the Steep Canyon Rangers on A Prairie Home Companion and began a two-month U.S. tour with the Rangers in September, including appearances at the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass festival, Carnegie Hall and Benaroya Hall in Seattle.[76][77] In November, they went on to play at the Royal Festival Hall in London with support from Mary Black.[78] In 2010, Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers appeared at the New Orleans Jazzfest, Merlefest Bluegrass Festival in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, at Bonnaroo Music Festival, at the ROMP[79] Bluegrass Festival in Owensboro, Kentucky, at the Red Butte Garden Concert series,[80] and on the BBC's Later... with Jools Holland.[81] Martin performed "Jubilation Day" with the Steep Canyon Rangers on The Colbert Report on March 21, 2011, on Conan on May 3, 2011, and on BBC's The One Show on July 6, 2011.[82] Martin performed a song he wrote called "Me and Paul Revere"[83] in addition to two other songs on the lawn of the Capitol Building in Washington, DC, at the "Capitol Fourth Celebration" on July 4, 2011.[84] While on tour, Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers occasionally performed Martin's 1978 novelty hit song "King Tut" live in a bluegrass arrangement. One of these performances was released on the 2011 album Rare Bird Alert.[85] In 2011, Martin also narrated and appeared in the PBS documentary "Give Me The Banjo" chronicling the history of the banjo in America.[86]

Love Has Come for You, a collaboration album with Edie Brickell, was released in April 2013.[87] The two made musical guest appearances on talk shows, such as The View and Late Show with David Letterman, to promote the album.[88][89][90] The title track won the Grammy Award for Best American Roots Song.[91] Starting in May 2013, he began a tour with the Steep Canyon Rangers and Edie Brickell throughout the United States.[92] In 2015, Brickell and Martin released So Familiar as the second installment of their partnership.[93] In 2017, Martin and Brickell appeared in the multi-award-winning documentary film The American Epic Sessions directed by Bernard MacMahon. Recording live direct-to-disc on the first electrical sound recording system from the 1920s,[94] they performed a version of "The Coo Coo Bird" a traditional song that Martin learned from the 1960s folk music group The Holy Modal Rounders.[95] The song was featured on the film soundtrack, Music from The American Epic Sessions released on June 9, 2017.[94]

In 2010, Martin created the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass, an award established to reward artistry and bring greater visibility to bluegrass performers.[96] The prize includes a US$50,000 cash award, a bronze sculpture created by the artist Eric Fischl, and a chance to perform with Martin on Late Show with David Letterman. Recipients include Noam Pikelny of the Punch Brothers band (2010),[97] Sammy Shelor of Lonesome River Band (2011),[98] Mark Johnson (2012),[99][100] Jens Kruger (2013),[101] Eddie Adcock (2014),[102] Danny Barnes (2015), Rhiannon Giddens (2016), Scott Vestal (2017), Kristin Scott Benson (2018),[103] and Victor Furtado (2019).[104]

Personal life

[edit]At the beginning of his career in comedy, Martin dated writer and artist Eve Babitz, who suggested he dress in what became his trademark white suit.[105] From 1977 to 1980, Martin was in a relationship with Bernadette Peters, with whom he co-starred in The Jerk and Pennies from Heaven. He also dated Karen Carpenter, Mary Tyler Moore and Anne Heche, who wrote about their relationship in her memoir.[106] On November 20, 1986, Martin married actress Victoria Tennant, with whom he co-starred in All of Me and L.A. Story. They divorced in 1994.[107]

Martin went on a USO Tour to Saudi Arabia during Operation Desert Storm from October 14 to 21, 1990. He met with military service men and women all over the region signing thousands of autographs and posing for pictures.[108] "Everybody coming out here, giving up part of their lives for this effort. I had some time off, and I felt kind of bad just sitting there," Martin said, "so I came."[109]

On July 28, 2007, Martin married writer and former New Yorker staff member Anne Stringfield.[110] Bob Kerrey presided over the ceremony at Martin's Los Angeles home. Lorne Michaels served as best man.[110] The nuptials came as a surprise to several guests, who had been told they were coming for a party.[110] In December 2012, Martin became a father when Stringfield gave birth to their daughter.[111][112]

Martin has been an avid art collector since 1968, when he bought a print by Ed Ruscha.[113] In 2001, the Bellagio Gallery of Fine Art presented a five-month exhibit of twenty-eight items from Martin's collection, including works by Roy Lichtenstein, Pablo Picasso, David Hockney, and Edward Hopper.[114] In 2006, he sold Hopper's Hotel Window (1955)[115] at Sotheby's for $26.8 million.[116] In 2015, working with two other curators, he organized an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and several other locations called, "The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris," featuring the works of Canadian painter and Group of Seven co-founder Lawren Harris.[117]

In July 2004, Martin purchased what he believed to be Landschaft mit Pferden (Landscape with Horses), a 1915 work by Heinrich Campendonk, from a Paris gallery for approximately €700,000. Fifteen months later, he sold the painting at a Christie's auction to a Swiss businesswoman for €500,000. The painting was later discovered to be a forgery. Police believe the fake Campendonk originated from a collection devised by a German forgery ring led by Wolfgang Beltracchi, pieces from which had been sold to French galleries.[118] Martin only discovered the fact that the painting had been fake many years after it had been sold at the auction. Concerning the experience, Martin said that the Beltracchis "were quite clever in that they gave it a long provenance and they faked labels, and it came out of a collection that mingled legitimate pictures with faked pictures."[119][120]

Martin was on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art board of trustees from 1984 to 2004.[121] Martin assisted in launching the National Endowment for Indigenous Visual Arts (NEIVA), a fund to support Australian Indigenous artists in 2021. Martin has supported Indigenous Australian painting previously. He organized an exhibition in 2019 with Gagosian Gallery titled "Desert Painters of Australia", which featured art by George Tjungurrayi and Emily Kame Kngwarreye.[122]

Martin has tinnitus; the condition was first attributed to filming a pistol shooting scene for Three Amigos in 1986,[123][124] but Martin later clarified that the tinnitus was actually from years of listening to loud music and performing in front of noisy crowds.[125]

Influences

[edit]

Martin has said that his comedy influences include Charlie Chaplin, Laurel and Hardy, Jack Benny, Jerry Lewis, and Woody Allen.[126][127]

On The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, he mentioned that Jerry Seinfeld is one of his "retro heroes", "a guy who came up behind me and is better than I am. I think he's fantastic, I love to listen to him, he almost puts me at peace. I love to listen to him talk".[128]

Martin's offbeat, ironic, and deconstructive style of humor has influenced many comedians during his career including Tina Fey, Steve Carell, Conan O'Brien, Jon Stewart,[129] Stephen Colbert, Robert Smigel, Bo Burnham,[130] and Jordan Peele.[131] Singer and composer Mike Patton cited Steve Martin as being an early influence[132] saying that he identifies with Martin.[133]

Filmography

[edit]Awards and nominations

[edit]Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]| Album | Year | Peak chart positions | Certifications [134] |

Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billboard 200 [135] |

US Bluegrass [136] | ||||

| Let's Get Small | 1977 | 10 | — |

|

Comedy |

| A Wild and Crazy Guy | 1978 | 2 | — |

| |

| Comedy Is Not Pretty! | 1979 | 25 | — |

| |

| The Steve Martin Brothers | 1981 | 135 | — | ||

| The Crow: New Songs for the 5-String Banjo | 2009 | 93 | 1 | Music | |

| Rare Bird Alert[137] (with Steep Canyon Rangers) |

2011 | 43 | 1 | ||

| Love Has Come for You[138] (with Edie Brickell) |

2013 | 21 | 1 | ||

| Live (with Steep Canyon Rangers featuring Edie Brickell) |

2014 | — | 1 | ||

| So Familiar (with Edie Brickell)[139] |

2015 | 126 | 1 | ||

| The Long-Awaited Album[140] (with Steep Canyon Rangers) |

2017 | 189 | 1 | ||

| "—" denotes a title that did not chart. | |||||

Singles

[edit]| Title | Year | Peak chart positions US [141] |

Album | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| "Grandmother's Song" | 1977 | 72 | Let's Get Small | Comedy |

| "King Tut" | 1978 | 17 | A Wild and Crazy Guy | Music |

| "Cruel Shoes" | 1979 | 91 | Comedy Is Not Pretty | Comedy |

| "Bluegrass Radio" (with Alison Brown featuring Sam Bush, Stuart Duncan, Trey Hensley, and Todd Phillips) |

2024 | — | Non-album single | Music |

Music videos

[edit]| Video | Year | Director |

|---|---|---|

| "Jubilation Day"[142] | 2011 | Ryan Reichenfeld |

| "Pretty Little One"[143] | 2014 | David Horn |

| "Won't Go Back"[144] (with Edie Brickell) |

2015 | Matt Robertson |

| "Caroline" | 2017 | Brian Petchers |

| "So Familiar" | 2018 | Laurence Jacobs |

| "Promontory Point" | ||

| "Bluegrass Radio" (with Alison Brown featuring Sam Bush, Stuart Duncan, Trey Hensley, and Todd Phillips) |

2024 | — |

Stand-up specials

[edit]- Steve Martin and Martin Short: An Evening You Will Forget for the Rest of Your Life, 2018

Other video releases

[edit]- Steve Martin-Live! (1986, VHS; includes short film "The Absent-Minded Waiter and footage from a 1979 concert)

- Saturday Night Live: The Best of Steve Martin (1998, DVD/VHS; sketch compilation)

- Steve Martin: The Television Stuff (2012, DVD; includes content of Steve Martin-Live! as well as his NBC specials and other television appearances)

Bibliography

[edit]Books and plays

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1977 | Cruel Shoes | collection of essays and short stories, first widely published in 1979 |

| 1993 | Picasso at the Lapin Agile and Other Plays: Picasso at the Lapin Agile, the Zig-Zag Woman, Patter for the Floating Lady, WASP |

plays |

| 1998 | Pure Drivel | collection of essays and short stories |

| 2000 | Shopgirl | novella |

| 2001 | Kindly Lent Their Owner: The Private Collection of Steve Martin | nonfiction |

| 2002 | The Underpants: A Play | play |

| 2003 | The Pleasure of My Company | novel |

| 2005 | The Alphabet from A to Y with Bonus Letter Z | children's book |

| 2007 | Born Standing Up | nonfiction |

| 2010 | An Object of Beauty | novel |

| Late for School | children's book | |

| 2012 | The Ten, Make That Nine, Habits of Very Organized People. Make That Ten.: The Tweets of Steve Martin | collection of tweets |

| 2014 | Bright Star | musical with Edie Brickell |

| 2016 | Meteor Shower | play |

| 2020 | A Wealth of Pigeons | collection of cartoons with Harry Bliss |

| 2022 | Number One Is Walking: My Life in the Movies and Other Diversions | memoir with illustrations by Harry Bliss |

| 2023 | So Many Steves: Afternoons with Steve Martin | audiobook cowritten with Adam Gopnik |

Screenplays

[edit]| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1977 | The Absent-Minded Waiter | short film |

| 1979 | The Jerk | with Michael Elias and Carl Gottlieb |

| 1982 | Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid | with Carl Reiner and George Gipe |

| 1983 | The Man with Two Brains | with Carl Reiner and George Gipe |

| 1986 | Three Amigos | with Lorne Michaels and Randy Newman |

| 1987 | Roxanne | based on Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand |

| 1991 | L.A. Story | screenplay first published in 1987 with Roxanne as Two Screenplays |

| 1994 | A Simple Twist of Fate | based on the 1861 novel Silas Marner by George Eliot |

| 1999 | Bowfinger | |

| 2005 | Shopgirl | based on his novella of the same name |

| 2006 | The Pink Panther | with Len Blum |

| 2008 | Traitor | story only; with Jeffrey Nachmanoff |

| 2009 | The Pink Panther 2 | with Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber |

Essays, reporting and other contributions

[edit]- Danto, Arthur C. (2001). Eric Fischl 1970–2000. Afterword by Steve Martin. New York: Monacelli Press.

- Modern Library Humor and Wit Series (2000) (Introduction and series editor)

- Martin, Steve (February 13, 2000) [published February 21 & 28, 2000]. "Two menus". Shouts & Murmurs. The New Yorker. Vol. 97, no. 27. p. 25. Archived from the original on August 30, 2021.

References

[edit]- ^ "Academy Unveils 2013 Governors Awards: Honorees Angelina Jolie, Angela Lansbury, Steve Martin, Piero Tosi". Deadline Hollywood. September 5, 2013. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ "Comedy Central's 100 Greatest Stand-Ups of all Time". Everything2. April 18, 2014.

- ^ Singer, Leigh (February 19, 2009). "Oscars: the best actors never to have been nominated". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "Steve Martin and Martin Short's Friendship Timeline". People. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "Steve Martin – Artist". grammy.com. November 23, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Whiteley, Sandy (2002). On This Date. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 204. ISBN 978-0071398275.

- ^ "Universal Men". Spin. Vol. 15, no. 9. September 1999. p. 94. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^ Walker (1998), p. 1.

- ^ Walker, Morris (2001). Steve Martin: The Magic Years. New York: SP Books. p. 2. ISBN 978-1561719808.

- ^ "Ancestry of Steve Martin". Wargs.com. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Jennifer Garcia (June 11, 2015). "Steve Martin's Life in Pictures in PEOPLE". PEOPLE.com. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Martin (2007), pp. 20–39.

- ^ "Top 5: Famous former male cheerleaders". The Washington Times. February 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Corliss, Richard (November 15, 2007). "Steve Martin, a Mild and Crazy Guy". Time. Archived from the original on December 20, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ Wills, Dominic. "Steve Martin – Biography". TalkTalk. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ Martin (2007), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Martin (2007), p. 39.

- ^ Walker (1998), p. 40.

- ^ Martin (2007), p. 65.

- ^ a b Fong-Torres, Ben (February 18, 1982). "Steve Martin's New Song and Dance (Steve Martin Sings)". Rolling Stone. ISBN 9781626743212. Retrieved June 18, 2022 – via Conversations with Steve Martin (University Press of Mississippi).

- ^ a b c d Martin, Steve (February 2008). "Being Funny: How the path-breaking comedian got his act together". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on December 27, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Steve Martin at IMDb

- ^ "SteveMartin.com | Stop the Presses". Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ Martin (2007), p. 76.

- ^ "Steve Martin". Television Academy.

- ^ Martin (2007), p. 77.

- ^ Freeman, Marc – 'The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour' at 50: The Rise and Fall of a Groundbreaking Variety Show. Hollywood Reporter. November 25, 2017 ("It has been shown that more people watch TV than any other appliance.")

- ^ Garlen, Jennifer C.; Graham, Anissa M. (2009). Kermit Culture: Critical Perspectives on Jim Henson's Muppets. McFarland & Company. p. 16. ISBN 978-0786442591.

- ^ a b Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York City: Basic Books. pp. 36–37. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- ^ "King Tut" Video on YouTube. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (November 7, 2012). "Steve Martin: The Television Stuff". The A.V. Club. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Sam (November 18, 2007). "Rationalist of the Absurd: Steve Martin's extraordinarily calculated comedy". New York. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ Martin (2007), pp. 176–177.

- ^ O'Reilly, Terry (February 8, 2018). "How A Wardrobe Change Transformed Steve Martin's Career". Under the Influence. CBC Radio One. Pirate Radio. Retrieved February 18, 2018.

- ^ Young, Alex (February 19, 2016). "After losing a bet to Jerry Seinfeld, Steve Martin performs his first stand-up comedy set in 35 years". Consequence. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Czajkowski, Elise (February 19, 2016). "Jerry Seinfeld and Steve Martin standup comedy review – superbly honed". The Guardian.

- ^ Husband, Andrew (May 25, 2018). "Steve Martin And Martin Short Embrace The Past Even When They Shun It". Forbes. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Leeson, Jef (2021). "The Funnier Side Of Eastern Canada". IMDb. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ Brummel, Chris (2010). "The Jerk: That Movie About Hating Cans". Archived from the original on June 13, 2008. Retrieved June 19, 2010.

- ^ American film Volume 7. 1981. American Film Institute, Arthur M. Sackler Foundation

- ^ "All of Me". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (September 21, 1984). "Steve Martin in 'All of Me'". The New York Times. p. C6. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Carignano, Tina (September 21, 1984). "Martin and Tomlin Get Their Act Together in All of Me". The Greyhound. Loyola College. Retrieved September 7, 2022 – via Internet Archive Digital Library.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (July 26, 1983). "The Talk of Hollywood: At The Studios, Star Billing Means a Parking Space". The New York Times. p. C11. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2022.

- ^ Semlyen, Nick de (May 26, 2020). Wild and Crazy Guys: How the Comedy Mavericks of the '80s Changed Hollywood Forever. Crown. ISBN 9781984826664.

- ^ Gallo, Hank (December 15, 1988). "Steve Martin leaves stand-up comedy behind, scans horizon for next role". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Singer, Leigh (February 19, 2009). "Oscars: the best actors never to have been nominated". The Guardian. London. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie (January 17, 2020). "Steve Martin & Martin Short Comedy Series From Dan Fogelman Ordered By Hulu". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Otterson, Joe (August 7, 2020). "Selena Gomez Joins Steve Martin, Martin Short in Hulu Comedy 'Only Murders in the Building'". Variety. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Echebiri, Makuochi (August 10, 2022). "Steve Martin Will Not Pursue New Roles After 'Only Murders In The Building' Ends". Collider. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- ^ a b But Seriously, Folks: Steve Martin talks about his first novella, a delicate, poignant modern romance about a shy shopgirl. Time article. October 16, 2000. Retrieved August 14, 2010

- ^ Grossman, Lev (December 9, 2007). "Born Standing Up review". Time. Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2022.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (November 28, 2010). "A New York Tale of Art, Money and Ambition". The New York Times. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ "Steve Martin teaming with Harry Bliss on 'Bliss' cartoons". Tribune Content Agency. April 2, 2019. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ Polston, Pamela (April 17, 2019). "Cartoonist Harry Bliss Collaborates With Comedian Steve Martin". Seven Days. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- ^ "Book Review: A Wealth of Pigeons". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "Number One Is Walking". Macmillan. Retrieved October 12, 2022.

- ^ History: Picasso At The Lapin Agile. Oct. 13, 1993 – May. 12, 1994. Steppenwolf Theatre Company Archived May 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 14, 2010

- ^ "Of arts and sciences". by Steve Martin. Article in The Observer (Oregon). March 13, 2009. Retrieved December 19. 2017

- ^ Pearson, Vince. "Edie Brickell, Steve Martin Broadway Bound With 'Bright Star'". NPR.org. NPR. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Isherwood, Charles (September 29, 2014). "Love, Loss and Local Color Make a Bluegrass Musical". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (August 7, 2016). "New Steve Martin Play Meteor Shower Opens in California Tonight". Playbill. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Rizzo, Frank (October 10, 2016). "Connecticut Theater Review: 'Meteor Shower' by Steve Martin". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Cox, Gordon. "Amy Schumer to Make Broadway Debut in Steve Martin's 'Meteor Shower' " Variety, August 7, 2017

- ^ Gerard, Jeremy. "Broadway Review: Amy Schumer Splashes 'Meteor Shower' With A Burst Of Starlight" Deadline Hollywood, November 29, 2017

- ^ "Amy Schumer delights in Steve Martin's new comedy Meteor Shower: EW review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ "Steve Martin and Alec Baldwin to Host Oscar Show". Margaret Herrick Library (Press release). Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. November 3, 2009. Archived from the original on November 7, 2009. Retrieved November 13, 2024.

- ^ "Monty Python: 30 years of near reunions from the comedy troupe". Digital Spy. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ McCall, Douglas (November 12, 2013). Monty Python: A Chronology, 1969–2012, 2d ed. McFarland. ISBN 9780786478118

- ^ "Steve Martin Plays The Banjo Really Well (Video)". October 6, 2009. HuffPost. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (August 5, 2009). "Steve Martin brings it all home with his banjo". The Guardian. Retrieved May 15, 2010

- ^ "Steve Martin's 2010 Banjo Tour". SteveMartin.com. March 4, 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Steve Martin To Make Grand Ole Opry Debut". April 1, 2009. Billboard. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ Walcott, Escher (June 2, 2023). "Kelly Clarkson Drops New Single 'I Hate Love' — Featuring Steve Martin on Banjo!". People. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Despres, Tricia (March 23, 2023). "Alison Brown Knew She Couldn't Finish 'Foggy Morning Breaking' Alone". People.com. Retrieved December 3, 2024.

- ^ "Benaroya Hall Calendar, Seattle Symphony Orchestra". Archived from the original on June 9, 2011.

- ^ Madison, Tjames (August 4, 2009). "Steve Martin and his banjo map fall tour". LiveDaily. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ Gill, Andy (November 10, 2009). "Steve Martin with The Steep Canyon Rangers, Royal Festival Hall, London". The Independent.

- ^ "ROMP 2011: Bluegrass Roots & Branches Festival". International Bluegrass Music Museum. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010.

- ^ "Concerts: Red Butte Garden 2010 Outdoor Concert Series". Red Butte Garden. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah. 2010. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2021.

- ^ "Later... with Jools Holland, Series 35, Episode 9". BBC. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ Tobey, Matt (March 21, 2011). "This Week on the Colbert Report: Steve Martin". Comedy Partners. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Barker, Olivia (June 29, 2011). "Steve Martin's 'Paul Revere' picks away at history". USA Today.

- ^ "A Capitol Fourth: Watch Steve Martin Sizzle". PBS. July 3, 2011. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Allmusic review

- ^ Martin, Steve (October 31, 2011). "Give Me The Banjo (Trailer)". PBS. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen (April 14, 2013). "First Listen: Steve Martin And Edie Brickell, 'Love Has Come For You'". NPR. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Bauer, Scott (April 22, 2013). "Steve Martin and Edie Brickell's 'Love Has Come For You': Collaboration A Perfect Blend of Traditional, Modern". HuffPost. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Late Show with Stephen Colbert". YouTube. March 16, 2016.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (April 19, 2013). "Steve Martin and Edie Brickell's 'Love Has Come For You'". The New York Times.

- ^ "Grammy Awards Past Winners Search (Steve Martin)". The Recording Academy. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- ^ "Steve Martin and The Steep Canyon Rangers featuring Edie Brickell Announce North American Tour". SteveMartin.com. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- ^ "Steve Martin and Edie Brickell on 'Unexplored Territory' of New Album". Rolling Stone. October 29, 2015. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ a b "American Epic: The Collection & The Soundtrack Out May 12th". Legacy Recordings. April 28, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ MacMahon, Bernard (September 28, 2016). "An Interview with Bernard MacMahon". Breakfast Television (Interview). Interview with Jill Belland. Calgary: City

- ^ "The Steve Martin Banjo Prize". FreshGrass Foundation. Archived from the original on March 14, 2022. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 15, 2010). "Steve Martin Creates Steve Martin Bluegrass Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 6, 2011). "Steve Martin Honors Another Banjo Player". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Lawless, John (September 6, 2012). "Mark Johnson wins 2012 Steve Martin Prize". Bluegrass Today. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 20, 2012). "Steve Martin Awards Third Annual Bluegrass Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 11, 2013). "Steve Martin's Prize for Bluegrass Goes to Jens Kruger". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 15, 2014). "Veteran Banjo Player Wins Bluegrass Honor: The Steve Martin Prize Goes to Eddie Adcock". The New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (September 24, 2018). "Steve Martin 2018 banjo prize goes to Kristin Scott Benson". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ Lawless, John (September 11, 2019). "Victor Furtado wins 2019 Steve Martin Banjo Prize". Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Anolik, Lili (March 2014). "All About Eve—and Then Some". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

There was this great French photographer, Henri Lartigue. He took pictures of Paris in the 20s. All his people wore white. I showed his photographs to Steve. 'You've got to look like this,' I said.

- ^ "Star tracks". Chicago Tribune. December 27, 1982.

- ^ Novak, Lauren (April 12, 2024). "Steve Martin Opens Up About the Truth of His Marriage to Anne Stringfield". Remind. Retrieved July 24, 2024.

- ^ McCombs, Phil (November 16, 1990). "USO's Desert No-Show". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Jehl, Douglas (October 17, 1990). "He Can't Be 'Wild and Crazy Guy': Saudi Arabia: Steve Martin went to the gulf to put on a show for the troops, but all he was allowed to do was press the flesh and sign autographs". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Steve Martin weds girlfriend Anne Stringfield". USA Today. AP. July 29, 2007. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008.

- ^ "Steve Martin becomes first-time dad at age 67". Archived from the original on April 11, 2013.

- ^ "Steve Martin is a dad for the first time at age 67". National Post. Toronto. February 14, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ Glueck, Grace (April 24, 2001). "In Vegas, Steve Martin Tries a Different Kind of Show". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2018.

- ^ Snedeker, Lisa (June 10, 2001), Las Vegas Casinos Gamble on Art as a Crowd Pleaser Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Vogel, Carol (October 6, 2006). "Edward Hopper Paintings Change at Whitney Show". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 18, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ Pollock, Lindsay (November 29, 2006). "Steve Martin Hopper, Wistful Rockwell Break Auction Records". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Martin adds curator to resume, The New York Times. Retrieved June 17, 2022

- ^ "Steve Martin Swindled: German Art Forgery Scandal Reaches Hollywood". Der Spiegel. May 30, 2011. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

- ^ Child, Ben (June 1, 2011). "Steve Martin victim of German art forgery gang". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "The Long Game: how Wolfgang Beltracchi conned the art world". Art Critique. January 24, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ Reynolds, Christopher (June 17, 2005). "Crowds Greet Return of the King at LACMA". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Solomon, Tessa (February 11, 2021). "Aiming to Grow Market, Steve Martin Helps Launch Fund for Australian Indigenous Artists". ARTnews. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Amy (2005). The new book of lists: the original compendium of curious information. New York: Cannongate. ISBN 978-1841957197.

- ^ "How to manage tinnitus". utahbesthearingaids.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2022.

- ^ "Steve Martin – Pitchfork". Pitchfork. October 27, 2015.

- ^ "It wasn't in the script: Carrie Fisher interviews Steve Martin about writing". Los Angeles Times. July 25, 1999. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ "Steve's Comedic Inspirations". MasterClass. Archived from the original on January 28, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ Steve Martin Is A Polymath: Click To Find Out What That Means! on YouTube published September 29, 2017 The Late Show with Stephen Colbert

- ^ Blitz, Michael (July 15, 2014). Jon Stewart: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313358296. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ McCarthy, Sean L. (October 29, 2010). "Bo Burnham Lists 'My Favorite Comedians' and Releases a Confessional Video: "Art Is Dead"". The Comic's Comic.

- ^ Lezmi, Josh (March 30, 2019). "Jordan Peele Reveals 2 Major Comedic Influences". Showbiz Cheat Sheet. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ "Mr. Bungle Radio Interview (For Locals Only) 1988". For Locals Only. Arcata, California: KFMI (published September 7, 2017). June 1, 1988. Event occurs at 19:04–19:31. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- ^ Gitter, Mike (August 25, 1990). "Facts Not Fiction". Kerrang!. No. 305. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Chart History – Steve Martin: Billboard 200". Billboard. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ Peak positions for Bluegrass albums on Billboards Bluegrass Albums Chart:

- For "The Crow: New Songs for the 5-String Banjo" "Bluegrass Albums". Billboard. February 21, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- For "Rare Bird Alert" "Bluegrass Albums". Billboard. April 2, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- For "Love Has Come for You" "Bluegrass Albums". Billboard. May 11, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- For "Live (with Steep Canyon Rangers featuring Edie Brickell) " "Bluegrass Albums". Billboard. May 29, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- For "So Familiar" "Bluegrass Albums". Billboard. November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- For "The Long-Awaited Album" "Bluegrass Albums". Billboard. October 14, 2017. Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- ^ "Rare Bird Alert". Rounder Records. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on March 21, 2011. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ "Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers Launch Tour". All Access. February 21, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ Edwards, Fred (August 20, 2015). "Steve Martin & Edie Brickell Announce Second Album 'So Familiar'". Billboard. Retrieved September 16, 2015.

- ^ Willman, Chris (September 22, 2017). "Album Review: Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers, 'The Long-Awaited Album'". Variety. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ "Steve Martin – Billboard Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "CMT : Videos : Steve Martin : Jubilation Day". Country Music Television. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "CMT : Videos : Steve Martin : Pretty Little One". Country Music Television. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2014.

- ^ Carr, Courtney (October 22, 2015). "See Steve Martin and Edie Brickell's 'Won't Go Back' Music Video". The Boot. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

General and cited sources

[edit]- Martin, Steve (2007). Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life. Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4165-6974-9.

- Walker, Morris (1998). Steve Martin: The Magic Years. SPI Books. ISBN 978-1-5617-1980-8.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Steve Martin at IMDb

- Steve Martin at the TCM Movie Database

- Talking About Steve Martin at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Steve Martin on National Public Radio: 2008 Morning Edition interview

- Steve Martin on National Public Radio: 2003 Fresh Air interview

- Steve Martin on Charlie Rose

- Steve Martin's Orange County Orange County Register A review including some of the earlier gigs in his career.

- Interview with Steve Martin, Chevy Chase, Martin Short about The Three Amigos in 1986 from Texas Archive of the Moving Image

- Steve Martin

- 1945 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American comedians

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- 21st-century American comedians

- 21st-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male musicians

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American screenwriters

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- AFI Life Achievement Award recipients

- American art collectors

- American banjoists

- American people of English descent

- American people of French descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American people of Welsh descent

- American comedy musicians

- American comedy writers

- American dramatists and playwrights

- American male comedians

- American male dramatists and playwrights

- American male film actors

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male screenwriters

- American male television actors

- American male television writers

- American male voice actors

- American memoirists

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American sketch comedians

- American stand-up comedians

- American television writers

- Audiobook narrators

- California State University, Long Beach alumni

- Comedians from California

- Comedians from Texas

- Disney Legends

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Film producers from California

- Film producers from Texas

- Grammy Award winners

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Male actors from California

- Male actors from Inglewood, California

- Male actors from Waco, Texas

- Mark Twain Prize recipients

- Musicians from Inglewood, California

- People from Garden Grove, California

- People from Inglewood, California

- People from Waco, Texas

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Rounder Records artists

- Santa Ana College alumni

- Screenwriters from California

- Screenwriters from Texas

- Television producers from California

- Television producers from Texas

- The New Yorker people

- University of California, Los Angeles alumni

- Warner Records artists

- Writers Guild of America Award winners