Kleppe v. New Mexico

| Kleppe v. New Mexico | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 23, 1976 Decided June 17, 1976 | |

| Full case name | Thomas S. Kleppe, Secretary of the Interior v. New Mexico, et al. |

| Citations | 426 U.S. 529 (more) 96 S. Ct. 2285; 49 L. Ed. 2d 34 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | New Mexico v. Morton, 406 F. Supp. 1237 (D.N.M. 1975) |

| Holding | |

| The Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 was a constitutional exercise of congressional power under the property clause at least insofar as it was applied to prohibit the New Mexico Livestock Board from entering upon the public lands of the United States and removing wild burros under the New Mexico Estray Law. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

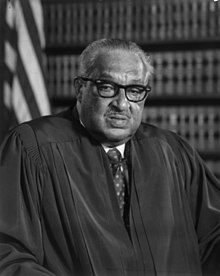

| Majority | Marshall, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 2; 16 U.S.C. § 1331, et seq. | |

Kleppe v. New Mexico, 426 U.S. 529 (1976), was a United States Supreme Court decision that unanimously held the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, passed in 1971 by the United States Congress to protect these animals from "capture, branding, harassment, or death", to be a constitutional exercise of congressional power. In February 1974, the New Mexico Livestock Board rounded up and sold 19 unbranded burros from Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land. When the BLM demanded the animals' return, the state filed suit claiming that the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act was unconstitutional, claiming the federal government did not have the power to control animals in federal lands unless they were items in interstate commerce or causing damage to the public lands.

Background

[edit]In 1971, Congress passed the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971, Pub. L. 92–195, 85 Stat. 649, enacted December 15, 1971 (later codified at 16 U.S.C. § 1331, et seq.) (WFRHBA). The act covered the management, protection and study of "unbranded and unclaimed horses and burros on public lands in the United States."[1][a] The act requires the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture to protect and manage wild horses as a component of public property of the United States.[3] Free ranging horses are to be protected from "capture, branding, harassment, or death."[4] The managing agencies are the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for Interior and the Forest Service (USFS) for Agriculture.[5]

The state of New Mexico challenged the federal government's authority to manage wild horses within the boundaries of New Mexico.[6] A New Mexican rancher, Kelly Stephenson, found wild burros grazing on his land and on the federal land where he had a grazing permit.[7][b] Stephenson complained to BLM, and when BLM refused to remove the burros, to the New Mexico Livestock Board.[9] The New Mexico Livestock Board, acting under state law[10] then seized nineteen burros from federal land and sold them at public auction.[11] The BLM asserted jurisdiction under the WFRHBA and demanded the return of the animals.[12] New Mexico then filed suit in the federal district court, claiming that the federal law was unconstitutional.[13]

District court

[edit]The case was heard by a three judge panel consisting of Oliver Seth, Edwin Mechem, and Harry Payne.[14] The panel declared the WFRHBA unconstitutional, stating that its authority was derived from the "territorial clause," Article IV of the United States Constitution,[15] but that animals do not become federal property simply by being on federal land.[16] Citing cases where the federal government regulated deer populations based on damage to federal lands, but arguing that the WFRHBA presented no evidence that horses or burros were inflicting damage,[c] the court enjoined the federal government from enforcing the Act, holding that the statute unconstitutionally exceeded the federal government's authority by protecting free-roaming horses and burros, rather than the land upon which they lived.[18]

Supreme Court

[edit]

Justice Thurgood Marshall delivered the opinion of a unanimous court. The Court interpreted the property clause broadly and found the WFRHBA a constitutional exercise of Congressional authority, holding, "the Property Clause also gives Congress the power to protect wildlife on the public lands, state law notwithstanding."[19] wrote that the "'complete power' that Congress has over public lands necessarily includes the power to regulate and protect the wildlife living there."[20] In addition, the Court said that Congress may enact legislation governing federal lands pursuant to the property clause and "when Congress so acts, federal legislation necessarily overrides conflicting state laws under the supremacy clause."[21]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The number of wild horses had decreased from an estimated 2,000,000 to as low as 9,500.[2][dubious – discuss]

- ^ Stephenson's issue appears to be that the burros were eating feed supplements that were intended for his cattle.[8]

- ^ This finding is particularly ironic given that the BLM's definition of a Herd Management Area (HMA) and calculation of Appropriate Management Level (AML) is based upon the ability of the habitat to support a given population of horses or burros.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ 16 U.S.C. § 1332.

- ^ Nadia Aksentijevich, Note: An American Icon in Limbo: How Clarifying the Standing Doctrine Could Free Wild Horses and Empower Advocates, 41 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 399, 402 (2014).

- ^ Aksentijevich, at 403.

- ^ 16 U.S.C. § 1331.

- ^ Roberto Iraola, Essay: The Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act Of 1971, 35 Envtl. L. 1049, 1051-52 (Fall 2005).

- ^ Blake Shepard, Article and Comment: The Scope Of Congress' Constitutional Power Under the Property Clause: Regulating Non-Federal Property to Further the Purposes of National Parks and Wilderness Areas, 11 B.C. Envtl. Aff. L. Rev. 479, 499 (Spring 1984).

- ^ New Mexico v. Morton, 406 F. Supp. 1237, 1237 (D.N.M. 1975).

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1237.

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1237.

- ^ New Mexico Estray Law, N.M. Stat. Ann. §§ 47-14-1 to 47-14-10 (1966).

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1237; Shepard, at 499.

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1237; Shepard, at 499.

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1237; Shepard, at 499.

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1237.

- ^ U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3, cl. 2.

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1238.

- ^ "Nevada–Wild Horses and Burros". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Morton, 406 F. Supp. at 1238-39.

- ^ Kleppe v. New Mexico, 426 U.S. 529, 546 (1976).

- ^ Kleppe, 426 U.S., at 541-42.

- ^ Kleppe, 426 U.S. at 543

Further reading

[edit]- Landres, Peter; Meyer, Shannon; Matthews, Sue (2001). "The Wilderness Act and Fish Stocking: An Overview of Legislation, Judicial Interpretation, and Agency Implementation". Ecosystems. 4 (4): 287–295. Bibcode:2001Ecosy...4..287L. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0011-6. S2CID 137750.

- Fischman, Robert L., and Jeremiah I. Williamson. "The Story of Kleppe v. New Mexico: The Sagebrush Rebellion as Un-Cooperative Federalism." University of Colorado Law Review 83 (2011): 123+ online

External links

[edit]- Text of Kleppe v. New Mexico, 426 U.S. 529 (1976) is available from: Findlaw Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)