Boy Scouts of America v. Dale

| Boy Scouts of America et al. v. Dale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 26, 2000 Decided June 28, 2000 | |

| Full case name | Boy Scouts of America and Monmouth Council, et al., Petitioners v. James Dale |

| Citations | 530 U.S. 640 (more) 120 S. Ct. 2446, 147 L. Ed. 2d 554, 2000 U.S. LEXIS 4487 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | 160 N.J. 562, 734 A.2d 1196, reversed and remanded |

| Holding | |

| A private organization is allowed, under certain criteria, to exclude a person from membership through their First Amendment right to freedom of association in spite of state antidiscrimination laws. New Jersey Supreme Court reversed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

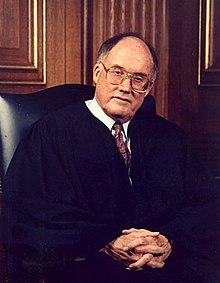

| Majority | Rehnquist, joined by O'Connor, Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas |

| Dissent | Stevens, joined by Souter, Ginsburg, Breyer |

| Dissent | Souter, joined by Ginsburg, Breyer |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. I | |

Boy Scouts of America et al. v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000), was a landmark decision of the US Supreme Court, decided on June 28, 2000, that held that the constitutional right to freedom of association allowed the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) to exclude a homosexual person from membership in spite of a state law requiring equal treatment of homosexuals in public accommodations. More generally, the court ruled that a private organization such as the BSA may exclude a person from membership when "the presence of that person affects in a significant way the group's ability to advocate public or private viewpoints".[1] In a 5–4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that opposition to homosexuality is part of BSA's "expressive message" and that allowing homosexuals as adult leaders would interfere with that message.[2]

The ruling reversed a decision of the New Jersey Supreme Court that had determined that New Jersey's public accommodations law required the BSA to readmit assistant Scoutmaster James Dale, who had come out and whom the BSA had expelled from the organization for that reason. Subsequently, the BSA lifted their bans on gay scouts and gay leaders in 2013 and 2015, respectively.

Background

[edit]

The Boy Scouts of America is a private, non-profit organization engaged in instilling its system of values in young people. At the time of the case, it asserted that homosexuality was inconsistent with those values.[2]

When Dale was a student at Rutgers University, he became co-president of the Lesbian/Gay student alliance. In July 1990, he attended a seminar on the health needs of lesbian and gay teenagers, where he was interviewed.[3] An account of the interview was published in a local newspaper in which Dale was quoted as saying he was gay. BSA officials read the interview and expelled Dale from his position as assistant Scoutmaster of a New Jersey troop.[4] Dale, an Eagle Scout, filed suit in the New Jersey Superior Court, alleging, among other things, that the Boy Scouts had violated the state statute prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in places of public accommodation.[5] The New Jersey Supreme Court ruled against the Boy Scouts, saying that they violated the State's public accommodations law by revoking Dale's membership based on his homosexuality.[6][7] Among other rulings, the court (1) held that application of that law did not violate the Boy Scouts' First Amendment right of expressive association because Dale's inclusion would not significantly affect members' ability to carry out their purposes; (2) determined that New Jersey has a compelling interest in eliminating the destructive consequences of discrimination from society, and that its public accommodations law abridges no more speech than is necessary to accomplish its purpose; and (3) held that Dale's reinstatement did not compel the Boy Scouts to express any message.[8]

The Boy Scouts appealed to the United States Supreme Court, which granted certiorari to determine whether the application of New Jersey's public accommodations law violated the First Amendment.

Counsel

[edit]

Dale was represented by Evan Wolfson, an attorney and noted LGBT rights advocate. Wolfson has also worked on a number of high-profile cases seeking legal recognition of same-sex marriages.[9] Also representing Dale on a pro bono basis was the New York-based law firm Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton.[3]

The Boy Scouts of America were represented by attorney George Davidson, a partner in the New York-based law firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed. Davidson is a former president of the Legal Aid Society and chair of the Federal Defenders of New York.

Decision

[edit]The Supreme Court decided 5–4 for the BSA on June 28, 2000.

Majority opinion

[edit]

Chief Justice William Rehnquist's majority opinion relied upon Roberts v. United States Jaycees, 468 U.S. 609, 622 (1984), in which the Supreme Court said: "Consequently, we have long understood as implicit in the right to engage in activities protected by the First Amendment a corresponding right to associate with others in pursuit of a wide variety of political, social, economic, educational, religious, and cultural ends." This right, the Roberts decision continues, is crucial in preventing the majority from imposing its views on groups that would rather express other, perhaps unpopular, ideas. Government actions that may unconstitutionally burden this freedom may take many forms, one of which is "intrusion into the internal structure or affairs of an association" like a "regulation that forces the group to accept members it does not desire". Forcing a group to accept certain members may impair the ability of the group to express those views, and only those views, that it intends to express. Thus, "freedom of association ... plainly presupposes a freedom not to associate."

However, to determine whether a group is protected by the First Amendment's expressive associational right, it must first be determined whether the group engages in "expressive association." After reviewing the Scout Oath and Scout Law the court decided that the general mission of the Boy Scouts is clear—it is "to instill values in young people".[10] The Boy Scouts seek to instill these values by having its adult leaders spend time with the youth members, instructing and engaging them in activities like camping, fishing, etc. During the time spent with the youth members, the Scoutmasters and assistant Scoutmasters inculcate them with the Boy Scouts' values—both expressly and by example. An association that seeks to transmit such a system of values engages in expressive activity.

- First, associations do not have to associate for the "purpose" of disseminating a certain message in order to be entitled to the protections of the First Amendment. An association must merely engage in expressive activity that could be impaired in order to be entitled to protection.

- Second, even if the Boy Scouts discourages Scout leaders from disseminating views on sexual issues, the First Amendment protects the Boy Scouts' method of expression. If the Boy Scouts wishes Scout leaders to avoid questions of sexuality and teach only by example, this fact does not negate the sincerity of its belief discussed above.

- Regarding whether the Boy Scouts as a whole had an expressive policy against homosexuality, the Court gave deference to the organization's own assertions of the nature of its expressions, as well as what would impair them. The Boy Scouts asserts that it "teach[es] that homosexual conduct is not morally straight", and that it does "not want to promote homosexual conduct as a legitimate form of behavior".[11] While the policy may not represent the views of all Boy Scouts, the First Amendment "does not require that every member of a group agree on every issue in order for the group's policy to be expressive association."[12] The Court deemed it sufficient that the Boy Scouts had taken an official position with respect to same-sex relationships. The presence of an openly gay activist in an assistant Scoutmaster's uniform sends a distinctly different message from the presence of a heterosexual assistant Scoutmaster who is on record as disagreeing with Boy Scouts policy. The Boy Scouts has a First Amendment right to choose to send one message but not the other. The fact that the organization does not trumpet its views from the housetops, or that it tolerates dissent within its ranks, does not mean that its views receive no First Amendment protection.[13]

The decision concluded:

We are not, as we must not be, guided by our views of whether the Boy Scouts' teachings with respect to homosexual conduct are right or wrong; public or judicial disapproval of a tenet of an organization's expression does not justify the State's effort to compel the organization to accept members where such acceptance would derogate from the organization's expressive message. While the law is free to promote all sorts of conduct in place of harmful behavior, it is not free to interfere with speech for no better reason than promoting an approved message or discouraging a disfavored one, however enlightened either purpose may strike the government.[14]

Dissenting opinion

[edit]

Justice Stevens wrote a dissent in which Justices Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer joined.[15] He observed that "every state law prohibiting discrimination is designed to replace prejudice with principle."[16] Justice Brandeis had observed in his dissent from New State Ice Company v. Liebmann (1932) that it "is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous State may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country".[16] In Stevens' opinion, the Court's decision interfered with New Jersey's experiment.

Stevens' first point was that the Boy Scouts' ban on gay members did not follow from its founding principles. The Boy Scouts sought to instill "values" in young people, "to prepare them to make ethical choices over their lifetime in achieving their full potential".[17] The Scout Oath and the Scout Law, which set forth the Scouts' central tenets, assist in this goal. One of these tenets is that a Scout is "morally straight". Another is that a Scout is "clean". As these terms were defined in the Scout Handbook, Stevens said, "it is plain as the light of day that neither one of these principles—'morally straight' and 'clean'—says the slightest thing about homosexuality. Indeed, neither term in the Boy Scouts' Law and Oath expresses any position whatsoever on sexual matters."[18]

What guidance the Boy Scouts gave to the adult leaders that have direct contact with the Scouts themselves urged those leaders to avoid discussing sexual matters. "Scouts... are directed to receive their sex education at home or in school, but not from the organization." Scoutmasters, in turn, are told to direct "curious adolescents" to their family, religious leaders, doctors, or other professionals. The Boy Scouts had gone so far as to devise specific guidelines for Scoutmasters:

- Do not advise Scouts about sexual matters, because it is outside the expertise and comfort level of most Scoutmasters.

- If a Scout brings specific questions to his Scoutmaster, the Scoutmaster should answer within his comfort level, remembering that a "boy who appears to be asking about sexual intercourse... may really only be worried about pimples".

- Boys with "sexual problems" should be referred to an appropriate professional.[19]

Stevens ended his dissent by noting that serious and "ancient" prejudices facing homosexuals could be aggravated by the "creation of a constitutional shield".[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000).

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

- ^ a b Greenhouse, Linda (June 29, 2000). "Supreme Court Backs Boy Scouts In Ban of Gays From Membership". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ a b "Boy Scouts v. Dale: Case History". Lambda Legal Defense & Education Fund. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006.

- ^ Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640, 697 (2000)

- ^ N.J. Stat. Ann. 10:5–4, 10:5–5 (2000).

- ^ Hanley, Robert (August 5, 1999). "New Jersey Court Overturns Ouster of Gay Boy Scout". The New York Times.

- ^ Hanley, Robert (March 3, 1998). "Appeals Court Finds in Favor Of Gay Scout". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ Dale v. Boy Scouts of America, 160 N.J. 562 (1999).

- ^ Baehr v. Miike

- ^ 530 U.S. at 650.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 653.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 655.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 655–56.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 661.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 663.

- ^ a b 530 U.S. at 664.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 666.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 668–69.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 669–70.

- ^ 530 U.S. at 699–700.

External links

[edit] Works related to Boy Scouts of America v. Dale at Wikisource

Works related to Boy Scouts of America v. Dale at Wikisource- Text of Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, 530 U.S. 640 (2000) is available from: Cornell CourtListener Findlaw Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)

- Koppelman, Andrew; Wolff, Tobias Barrington (July 7, 2009). A Right to Discriminate: How the Case of Boy Scouts of America V. James Dale Warped the Law of Free Association. Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-12127-8. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- 2000 in LGBTQ history

- 2000 in United States case law

- American Civil Liberties Union litigation

- Boy Scouts of America litigation

- Discrimination against LGBTQ people in the United States

- Supreme Court of New Jersey

- United States freedom of association case law

- United States LGBTQ rights case law

- United States Supreme Court cases of the Rehnquist Court

- Legal history of New Jersey

- United States Supreme Court cases