History

| Part of a series on |

| History |

|---|

|

History (derived from Ancient Greek ἱστορία (historía) 'inquiry; knowledge acquired by investigation')[1] is the systematic study and documentation of the past.[2][3] History is an academic discipline which uses a narrative to describe, examine, question, and analyse past events, and investigate their patterns of cause and effect.[4][5] Historians debate which narrative best explains an event, as well as the significance of different causes and effects. Historians debate the nature of history as an end in itself, and its usefulness in giving perspective on the problems of the present.[4][6][7][8]

The period of events before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory.[9] "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well as the memory, discovery, collection, organization, presentation, and interpretation of these events. Historians seek knowledge of the past using historical sources such as written documents, oral accounts or traditional oral histories, art and material artefacts, and ecological markers.[10]

Stories common to a particular culture, but not supported by external sources (such as the tales surrounding King Arthur), are usually classified as cultural heritage or legends.[11][12] History differs from myth in that it is supported by verifiable evidence. However, ancient cultural influences have helped create variant interpretations of the nature of history, which have evolved over the centuries and continue to change today. The modern study of history is wide-ranging, and includes the study of specific regions and certain topical or thematic elements of historical investigation. History is taught as a part of primary and secondary education, and the academic study of history is a major discipline in universities.

Herodotus, a 5th-century BCE Greek historian, is often considered the "father of history", as one of the first historians in the Western tradition,[13] though he has been criticized as the "father of lies".[14][15] Along with his contemporary Thucydides, he helped form the foundations for the modern study of past events and societies.[16] Their works continue to be read today, and the gap between the culture-focused Herodotus and the military-focused Thucydides remains a point of contention or approach in modern historical writing. In East Asia a state chronicle, the Spring and Autumn Annals, was reputed to date from as early as 722 BCE, though only 2nd-century BCE texts have survived. The title "father of history" has also been attributed, in their respective societies, to Sima Qian, Ibn Khaldun, and Kenneth Dike.[17][18][19]

Definition

As an academic discipline, history is the study of the past.[20] It conceptualizes and describes what happened by collecting and analysing evidence to construct narratives. These narratives cover not only how events unfolded but also why they happened and in which contexts, providing an explanation of relevant background conditions and causal mechanisms. History further examines the meaning of historical events and the underlying human motives driving them.[21]

In a slightly different sense, history refers to the past events themselves. In this sense, history is what happened rather than the academic field studying what happened. When used as a countable noun, a history is a representation of the past in the form of a history text. History texts are cultural products involving active interpretation and reconstruction. The narratives presented in them can change as historians discover new evidence or reinterpret already-known sources. The nature of the past itself, by contrast, is static and unchangeable.[22] Some historians focus on the interpretative and explanatory aspects to distinguish histories from chronicles, arguing that chronicles only catalogue events in chronological order, whereas histories aim at a comprehensive understanding of their causes, contexts, and consequences.[23][a]

Traditionally, history was primarily concerned with written documents. It focused on recorded history since the invention of writing, leaving prehistory[b] to other fields, such as archaeology.[26] Today, history has a broader scope that includes prehistory, starting with the earliest human origins several million years ago.[27][c]

It is controversial whether history is a social science or forms part of the humanities. Like social scientists, historians formulate hypotheses, gather objective evidence, and present arguments based on this evidence. At the same time, history aligns closely with the humanities because of its reliance on subjective aspects associated with interpretation, storytelling, human experience, and cultural heritage.[29] Some historians strongly support one or the other classification while others characterize history as a hybrid discipline that does not belong to one category at the exclusion of the other.[30] History contrasts with pseudohistory, which deviates from historiographical standards by relying on disputed historical evidence, selectively ignoring genuine evidence, or using other means to distort the historical record. Often motivated by specific ideological agendas, pseudohistorians mimic historical methodology to promote misleading narratives that lack rigorous analysis and scholarly consensus.[31]

Purpose

Various suggestions about the purpose or value of history have been made. Some historians propose that its primary function is the pure discovery of the truth about the past. This view emphasizes that the disinterested pursuit of truth is an end in itself, while external purposes, associated with ideology or politics, threaten to undermine the accuracy of historical research by distorting the past. In this role, history also challenges traditional myths lacking factual support.[32]

A different perspective suggests that the main value of history lies in the lessons it teaches for the present. This view is based on the idea that an understanding of the past can guide decision-making, for example, to avoid repeating previous mistakes.[33] A related perspective focuses on a general understanding of the human condition, making people aware of the diversity of human behaviour across different contexts—similar to what one can learn by visiting foreign countries.[34] History can also foster social cohesion by providing people with a collective identity through a shared past, helping to preserve and cultivate cultural heritage and values across generations.[35]

History is sometimes used for political or ideological purposes, for instance, to justify the status quo by making certain traditions appear respectable or to promote change by highlighting past injustices.[36] Pushed to extreme forms, this can result in pseudohistory or historical denialism when evidence is intentionally ignored or misinterpreted to construct a misleading narrative serving external interests.[37]

Etymology

The word history comes from the Ancient Greek term ἵστωρ (histōr), meaning 'learned, wise man'. It gave rise to the Ancient Greek word ἱστορία (historiā), which had a wide meaning associated with inquiry in general and giving testimony. The term was later adopted into Classical Latin as historia. In Hellenistic and Roman times, the meaning of the term shifted, placing more emphasis on narrative aspects and the art of presentation rather than focusing on investigation and testimony.[38]

The word entered Middle English in the 14th century via the Old French term histoire.[39] At this time, it meant 'story, tale', encompassing both factual and fictional narratives. In the 15th century, its meaning shifted to cover the branch of knowledge studying the past in addition to narratives about the past.[40] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the word history became more closely associated with factual accounts and evidence-based inquiry, coinciding with the professionalization of historical inquiry.[41] The dual meaning, referring to both mere stories and factual accounts of the past, is present in the terms for history in many other European languages. They include the French histoire, the Italian storia, and the German Geschichte.[42]

Areas of study

History is a wide field of inquiry encompassing many branches. Some branches focus on a specific time period. Others concentrate on a particular geographic region or a distinct theme. Specializations of different types can usually be combined. For example, a work on economic history in ancient Egypt merges temporal, regional, and thematic perspectives. For topics with a broad scope, the amount of primary sources is often too extensive for an individual historian to review. This forces them to either narrow the scope of their topic or rely on secondary sources to arrive at a wide overview.[43]

By period

Chronological division is a common approach to organizing the vast expanse of history into more manageable segments. Different periods are often defined based on dominant themes that characterize a specific time frame and significant events that initiated these developments or brought them to an end. Depending on the selected context and level of detail, a period may be as short as a decade or longer than several centuries.[44] A traditionally influential approach divides human history into prehistory, ancient history, post-classical history, early modern history, and modern history.[45][d] Depending on the region and theme, the time frames covered by these periods can vary and historians may use entirely different periodizations.[47] For example, traditional periodizations of Chinese history follow the main dynasties,[48] and the division into pre-Columbian, colonial, and post-colonial periods plays a central role in the history of the Americas.[49]

Prehistory started with the evolution of human-like species several million years ago, leading to the emergence of anatomically modern humans about 200,000 years ago.[50] Subsequently, humans migrated out of Africa to populate most of the earth. Towards the end of prehistory, technological advances in the form of new and improved tools led many groups to give up their established nomadic lifestyle, based on hunting and gathering, in favour of a sedentary lifestyle supported by early forms of agriculture.[51] The absence of written documents from this period presents researchers with unique challenges. It results in an interdisciplinary approach relying on other forms of evidence from fields such as archaeology, anthropology, paleontology, and geology.[52]

Ancient history, starting roughly 3500 BCE, saw the emergence of the first major civilizations in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus Valley, China, and Peru. The new social, economic, and political complexities necessitated the development of writing systems. Thanks to advancements in agriculture, surplus food allowed these civilizations to support larger populations, accompanied by urbanization, the establishment of trade networks, and the emergence of regional empires. Meanwhile, influential religious systems and philosophical ideas were first formulated, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Judaism, and Greek philosophy.[53]

In post-classical history, beginning around 500 CE, the influence of religions continued to grow. Missionary religions, like Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam, spread rapidly and established themselves as world religions, marking a cultural shift as they gradually replaced local belief systems. Meanwhile, inter-regional trade networks flourished, leading to increased technological and cultural exchange. Conquering many territories in Asia and Europe, the Mongol Empire became a dominant force during the 13th and 14th centuries.[54]

In early modern history, starting roughly 1500 CE, European states rose to global power. As gunpowder empires, they explored and colonized large parts of the world. As a result, the Americas were integrated into the global network, triggering a vast biological exchange of plants, animals, people, and diseases.[e] The Scientific Revolution prompted major discoveries and accelerated technological progress. It was accompanied by other intellectual developments, such as humanism and the Enlightenment, which ushered in secularization.[56]

In modern history, beginning at the end of the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution transformed economies by introducing more efficient modes of production. Western powers established vast colonial empires, gaining superiority through industrialized military technology. The increased international exchange of goods, ideas, and people marked the beginning of globalization. Various social revolutions challenged autocratic and colonial regimes, paving the way for democracies. Many developments in fields like science, technology, economy, living standards, and human population accelerated at unprecedented rates. This happened despite the widespread destruction caused by two world wars, which rebalanced international power relations by undermining European dominance.[57]

By geographic location

Areas of historical study can also be categorized by the geographic locations they examine.[58] Geography plays a central role in history through its influence on food production, natural resources, economic activities, political boundaries, and cultural interactions.[59][f] Some historical works limit their scope to small regions, such as a village or a settlement. Others focus on broad territories that encompass entire continents, like the histories of Africa, Asia, Europe, the Americas, and Oceania.[61]

The history of Africa stands at the dawn of human history with the evolution of anatomically modern humans about 200,000 years ago.[62] The invention of writing and the establishment of civilization happened in ancient Egypt in the 4th millennium BCE.[63] Over the next millennia, other notable civilizations and kingdoms formed in Nubia, Axum, Carthage, Ghana, Mali, and Songhay.[64] Islam began spreading across North Africa in the 7th century CE and became the dominant faith in many empires. Meanwhile, trade along the trans-Saharan route intensified.[65] Beginning in the 15th century, millions of Africans were enslaved and forcibly transported to the Americas as part of the Atlantic slave trade.[66] Most of the continent was colonized by European powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[67] Among rising nationalism, African states gradually gained independence in the aftermath of World War II, a period that saw economic progress, rapid population growth, and struggles for political stability.[68]

In the history of Asia, anatomically modern humans arrived around 100,000 years ago.[69] As one of the cradles of civilization, Asia was home to some of the first ancient civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and China, which began to emerge in the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE.[70] In the following millennia, all major world religions and several influential philosophical traditions were conceived and spread, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam.[71] The Silk Road facilitated trade and cultural exchange across Eurasia, while powerful empires rose and fell, such as the Mongol Empire, which dominated the continent during the 13th and 14th centuries CE.[72] European influence grew over the following centuries, culminating in the 19th and early 20th centuries when many parts of Asia came under direct colonial control until the end of World War II.[73] The post-independence period was characterized by modernization, economic growth, and a steep increase in population.[74]

The history of Europe began about 45,000 years ago with the arrival of the first anatomically modern humans.[75] The Ancient Greeks laid the foundations of Western culture, philosophy, and politics in the first millennium BCE.[76] Their cultural heritage continued in the Roman Empire and later the Byzantine Empire.[77] The medieval period began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE and was marked by the spread of Christianity.[78] Starting in the 15th century, European exploration and colonization interconnected the globe, while cultural, intellectual, and scientific developments transformed Western societies.[79] From the late 18th to the early 20th centuries, European global dominance was further solidified by the Industrial Revolution and the establishment of large overseas colonies.[80] It came to an end because of the devastating effects of two world wars.[81] In the following Cold War era, the continent was divided into a Western and an Eastern bloc. They pursued political and economic integration after the Cold War ended.[82]

In the history of the Americas, the first anatomically modern humans arrived around 20,000 to 15,000 years ago.[83] The Americas were home to some of the earliest civilizations, like the Norte Chico civilization in South America and the Maya and Olmec civilizations in Central America.[84] Over the next millennia, major empires arose beside them, such as the Teotihuacan, Aztec, and Inca empires.[85] Following the arrival of the Europeans from the late 15th century onwards, the spread of newly introduced diseases drastically reduced the local population. Together with colonization and the massive influx of African slaves, it led to the collapse of major empires as demographic and cultural landscapes were reshaped.[86] Independence movements in the 18th and 19th centuries led to the formation of new nations across the Americas.[87] In the 20th century, the United States emerged as a dominant global power and a key player in the Cold War.[88]

The history of Oceania starts with the arrival of anatomically modern humans about 60,000 to 50,000 years ago.[89] They established diverse regional societies and cultures, first in Australia and Papua New Guinea and later also on other Pacific Islands.[90] The arrival of the Europeans in the 16th century prompted significant transformations. By the end of the 19th century, most of the region had come under Western control.[91] Oceania was dragged into various conflicts during the world wars and experienced decolonization in the post-war period.[92]

By theme

Historians often limit their inquiry to a specific theme belonging to a particular field.[93] Some historians propose a general subdivision into three major themes: political history, economic history, and social history. However, the boundaries between these branches are vague and their relation to other thematic branches, such as intellectual history, is not always clear.[94]

Political history studies the organization of power in society, examining how power structures arise, develop, and interact. Throughout most of recorded history, states or state-like structures have been central to this field of study. It explores how a state was organized internally, like factions, parties, leaders, and other political institutions. It also examines which policies were implemented and how the state interacted with other states.[95] Political history has been studied since antiquity, making it the oldest branch of history, while other major subfields have only become established branches in the past century.[96]

Diplomatic and military history are closely related to political history. Diplomatic history examines international relations between states. It covers foreign policy topics such as negotiations, strategic considerations, treaties, and conflicts between nations as well as the role of international organizations in these processes.[97] Military history studies the impact and development of armed conflicts in human history. This includes the examination of specific events, like the analysis of a particular battle and the discussion of the different causes of a war. It also involves more general considerations about the evolution of warfare, including advancements in military technology, strategies, tactics, and institutions.[98]

Economic history examines how commodities are produced, exchanged, and consumed. It covers economic aspects such as the use of land, labour, and capital, the supply and demand of goods, the costs and means of production, and the distribution of income and wealth. Economic historians typically focus on general trends in the form of impersonal forces, such as inflation, rather than the actions and decisions of individuals. If enough data is available, they rely on quantitative methods, like statistical analysis. For periods before the modern era, available data is often limited, forcing economic historians to rely on scarce sources and extrapolate information from them.[99]

Social history is a broad field investigating social phenomena, but its precise definition is disputed. Some theorists understand it as the study of everyday life outside the domains of politics and economics, including cultural practices, family structures, community interactions, and education. A closely related approach focuses on experience rather than activities, examining how members of particular social groups, like social classes, races, genders, or age groups, experienced their world. Other definitions see social history as the study of social problems, like poverty, disease, and crime, or take a broader perspective by examining how whole societies developed.[100] Closely related fields include cultural history, gender history, and religious history.[101]

Intellectual history is the history of ideas. It studies how concepts, philosophies, and ideologies have evolved. It is particularly interested in academic fields but not limited to them, including the study of the beliefs and prejudices of ordinary people. In addition to studying intellectual movements themselves, it also examines the cultural and social contexts that shaped them and their influence on other historical developments.[102] As closely related fields, the history of philosophy investigates the development of philosophical thought[103] while the history of science studies the evolution of scientific theories and practices.[104] The history of art, another connected discipline, examines historical works of art and the development of artistic activities, styles, and movements.[105]

Environmental history studies the relation between humans and their environment. It seeks to understand how humans and the rest of nature have affected each other in the course of history.[106] Other thematic branches include constitutional history, legal history, urban history, business history, history of technology, medical history, history of education, and people's history.[107]

Others

Some branches of history are characterized by the methods they employ, such as quantitative history and digital history, which rely on quantitative methods and digital media.[108] Comparative history compares historical phenomena from distinct times, regions, or cultures to examine their similarities and differences.[109] Unlike most other branches, oral history relies on oral reports rather than written documents. It reflects the personal experiences and interpretations of what common people remember about the past, encompassing eyewitness accounts, hearsay, and communal legends.[110] Counterfactual history uses counterfactual thinking to examine alternative courses of history, exploring what could have happened under different circumstances.[111] Certain branches of history are distinguished by their theoretical outlook, such as Marxist and feminist history.[112]

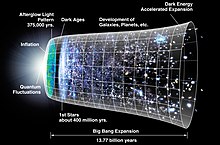

Some distinctions focus on the scope of the studied topic. Big history is the branch with the broadest scope, covering everything from the Big Bang to the present.[113] World history is another branch with a wide topic. It examines human history as a whole, starting with the evolution of human-like species.[114] The terms macrohistory, mesohistory, and microhistory refer to different scales of analysis, ranging from large-scale patterns that affect the whole globe to detailed studies of small communities, particular individuals, or specific events.[115] Closely related to microhistory is the genre of historical biography, which recounts an individual's life in its historical context and the legacy it left.[116]

Public history involves activities that present history to the general public. It usually happens outside the traditional academic settings in contexts like museums, historical sites, and popular media.[117]

Methods

The historical method is a set of techniques historians use to research and interpret the past, covering the processes of collecting, evaluating, and synthesizing evidence.[g] It seeks to ensure scholarly rigour, accuracy, and reliability in how historical evidence is chosen, analysed, and interpreted.[119] Historical research often starts with a research question to define the scope of the inquiry. Some research questions focus on a simple description of what happened. Others aim to explain why a particular event occurred, refute an existing theory, or confirm a new hypothesis.[120]

Sources and source criticism

To answer research questions, historians rely on various types of evidence to reconstruct the past and support their conclusions. Historical evidence is usually divided into primary and secondary sources.[121] A primary source is a source that originated during the period that is studied. Primary sources can take various forms, such as official documents, letters, diaries, eyewitness accounts, photographs, and audio or video recordings. They also include historical remains examined in archaeology, geology, and the medical sciences, such as artefacts and fossils unearthed from excavations. Primary sources offer the most direct evidence of historical events.[122]

A secondary source is a source that analyses or interprets information found in other sources.[123] Whether a document is a primary or a secondary source depends not only on the document itself but also on the purpose for which it is used. For example, if a historian writes a text about slavery based on an analysis of historical documents, then the text is a secondary source on slavery and a primary source on the historian's opinion.[124][h] Consistency with available sources is one of the main standards of historical works. For instance, the discovery of new sources may lead historians to revise or dismiss previously accepted narratives.[126] To find and access primary and secondary sources, historians consult archives, libraries, and museums. Archives play a central role by preserving countless original sources and making them available to researchers in a systematic and accessible manner. Thanks to technological advances, historians increasingly rely on online resources, which offer vast digital databases with efficient methods to search and access specific documents.[127]

Source criticism is the process of analysing and evaluating the information a source provides.[i] Typically, this process begins with external criticism, which evaluates the authenticity of a source. It addresses the questions of when and where the source was created and seeks to identify the author, understand their reason for producing the source, and determine if it has undergone some type of modification since its creation. Additionally, the process involves distinguishing between original works, mere copies, and deceptive forgeries.[129]

Internal criticism evaluates the content of a source, typically beginning with the clarification of the meaning within the source. This involves disambiguating individual terms that could be misunderstood but may also require a general translation if the source is written in an ancient language.[j] Once the information content of a source is understood, internal criticism is specifically interested in determining accuracy. Critics ask whether the information is reliable or misrepresents the topic and further question whether the source is comprehensive or omits important details. One way to make these assessments is to evaluate whether the author was able, in principle, to provide a faithful presentation of the studied event and to consider the influences of their intentions and prejudices. Being aware of the inadequacies of a source helps historians decide whether and which aspects of it to trust, and how to use it to construct a narrative.[131]

Synthesis and schools of thought

The selection, analysis, and criticism of sources result in the validation of a large collection of mostly isolated statements about the past. As a next step, sometimes termed historical synthesis, historians examine how the individual pieces of evidence fit together to form part of a larger story.[k] Constructing this broader perspective is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the topic as a whole. It is a creative aspect[l] of historical writing that reconstructs, interprets, and explains what happened by showing how different events are connected.[134] In this way, historians address not only which events occurred but also why they occurred and what consequences they had.[135] While there are no universally accepted techniques for this synthesis, historians rely on various interpretative tools and approaches in this process.[136]

One tool to provide an accessible overview of complex developments is the use of periodization. It divides a timeframe into different periods, each organized around central themes or developments that shaped the period. For example, the three-age system divides early human history into Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age based on the predominant materials and technologies during these periods.[137] Another methodological tool is the examination of silences, gaps or omissions in the historical record of events that occurred but did not leave significant evidential traces. Silences can happen when contemporaries find information too obvious to document but may also occur if there were specific reasons to withhold or destroy information.[138][m] Conversely, when large datasets are available, quantitative approaches can be used. For instance, economic and social historians commonly employ statistical analysis to identify patterns and trends associated with large groups.[141]

Different schools of thought often come with their own methodological implications for how to write history.[142] Positivists emphasize the scientific nature of historical inquiry, focusing on empirical evidence to discover objective truths.[143] In contrast, postmodernists reject grand narratives that claim to offer a single, objective truth. Instead, they highlight the subjective nature of historical interpretation, which leads to a multiplicity of divergent perspectives.[144] Marxists interpret historical developments as expressions of economic forces and class struggles.[145] The Annales school highlights long-term social and economic trends while relying on quantitative and interdisciplinary methods.[146] Feminist historians study the role of gender in history, with a particular interest in the experiences of women to challenge patriarchal perspectives.[147]

Related fields

Historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods and development of historical research. Historiographers examine what historians do, resulting in a metatheory in the form of a history of history. Some theorists use the term historiography in a different sense to refer to written accounts of the past.[148]

A central topic in historiography as a metatheory focuses on the standards of evidence and reasoning in historical inquiry. Historiographers examine and codify how historians use sources to construct narratives about the past, including the analysis of the interpretative assumptions from which they proceed. Closely related issues include the style and rhetorical presentation of works of history.[149]

By comparing the works of different historians, historiographers identify schools of thought based on shared research methods, assumptions, and styles.[150] For example, they examine the characteristics of the Annales school, like its use of quantitative data from various disciplines and its interest in economic and social developments taking place over extended periods.[151] Comparisons also extend to whole eras from ancient to modern times. This way, historiography traces the development of history as an academic discipline, highlighting how the dominant methods, themes, and research goals have changed over time.[152]

Philosophy

The philosophy of history[n] investigates the theoretical foundations of history. It is interested both in the past itself as a series of interconnected events and in the academic field studying this process. Insights and approaches from various branches of philosophy are relevant to this endeavour, such as metaphysics, epistemology, hermeneutics, and ethics.[154]

In examining history as a process, philosophers explore the basic entities that make up historical phenomena. Some approaches rely primarily on the beliefs and actions of individual humans, while others include collective and other general entities, such as civilizations, institutions, ideologies, and social forces.[155] A related topic concerns the nature of causal mechanisms connecting historic events with their causes and consequences.[156] One view holds that there are general laws of history that determine the course of events, similar to the laws of nature studied in the natural sciences. According to another perspective, causal relations between historic events are unique and shaped by contingent factors.[157] Some philosophers suggest that the general direction of the course of history follows large patterns. According to one proposal, history is cyclic, meaning that on a sufficiently large scale, individual events or general trends repeat. Another theory asserts that history is a linear, teleological process moving towards a predetermined goal.[158][o]

A philosophical topic regarding historical research is the possibility of an objective account of history. Various philosophers argue that this ideal is not achievable, pointing to the subjective nature of interpretation, the narrative aspect of history, and the influence of personal values on the perspective and actions of both historic individuals and historians. A different view states that there are hard historic facts about what happened, for example, facts about when a drought occurred or which army was defeated. This view acknowledges that obstacles to a neutral presentation exist but holds that they can be overcome, at least in principle.[160]

The topics of philosophy of history and historiography overlap as both are interested in the standards of historical reasoning. Historiographers typically focus more on describing specific methods and developments encountered in the study of history. Philosophers of history, by contrast, tend to explore more general patterns, including evaluative questions about which methods and assumptions are correct.[161] Historical reasoning is sometimes used in philosophy and other disciplines as a method to explain phenomena. This approach, known as historicism, argues that understanding something requires knowledge of its unique history or how it evolved. For instance, historicism about truth states that truth depends on historical circumstances, meaning that there are no transhistorical truths. Historicism contrasts with approaches that seek understanding based on timeless and universal principles.[162]

Education

History is part of the school curriculum in most countries.[163] Early history education aims to make students interested in the past and familiarize them with fundamental concepts of historical thought. By fostering a basic historical awareness, it seeks to instil a sense of identity by helping them understand their cultural roots.[164] It often takes a narrative form by presenting children with simple stories, which may focus on historic individuals or the origins of local holidays, festivals, and food.[165] More advanced history education encountered in secondary school covers a broader spectrum of topics, ranging from ancient to modern history, at both local and global levels. It further aims to acquaint students with historical research methodologies, including the abilities to interpret and critically evaluate historical claims.[166]

History teachers employ a variety of teaching methods. They include narrative presentations of historical developments, questions to engage students and prompt critical thinking, and discussions on historical topics. Students work with historical sources directly to learn how to analyse and interpret evidence, both individually and in group activities. They engage in historical writing to develop the skills of articulating their thoughts clearly and persuasively. Assessments through oral or written tests aim to ensure that learning goals are reached.[167] Traditional methodologies in history education often present numerous facts, like dates of significant events and names of historical figures, which students are expected to memorize. Alternative approaches seek to foster a more active engagement and a deeper understanding of general patterns, focusing not only on what happened but also on why it happened and its lasting historical significance.[168]

History education in state schools serves a variety of purposes. A key skill is historical literacy, the ability to understand, critically analyse, and respond to historical claims. By making students aware of significant developments in the past, they become familiar with various contexts of human life, helping them understand the present and its diverse cultures. At the same time, it fosters a sense of cultural identity and prepares students for active citizenship.[169] Knowledge of a shared past and cultural heritage contributes to the formation of a national identity. This political aspect of history education may spark disputes about which topics school textbooks should cover. In various regions, it has resulted in so-called history wars over the curriculum.[170] It can lead to a biased treatment of controversial topics in an attempt to present the national heritage in a favourable light.[171]

In addition to the formal education provided in public schools, history is also taught in informal settings outside the classroom. Public history takes place in locations like museums and memorial sites, where selected artefacts are often used to tell specific stories.[172] It includes popular history, which aims to make the past accessible and appealing to a wide audience of non-specialists in media such as books, television programmes, and online content.[173] Informal history education also happens in oral traditions as narratives about the past are transmitted across generations.[174]

Other fields

History employs an interdisciplinary methodology, drawing on findings from various disciplines, such as archaeology, geology, genetics, anthropology, and linguistics.[175] Archaeologists study man-made historical artefacts and other forms of material evidence. Their findings provide crucial insights into past human activities and cultural developments.[176] Geology and other earth sciences help historians understand the environmental contexts and physical processes that affected past societies, including climate conditions, landscapes, and natural events.[177] Genetics provides key information about the evolutionary origins of humans as a species, human migration, ancestry, and demographic changes.[178] Anthropologists investigate human culture and behaviour, such as social structures, belief systems, and ritual practices. This knowledge offers contexts for the interpretation of historical events.[179] Historical linguistics studies the development of languages over time, which can be crucial for the interpretation of ancient documents and can also provide information about migration patterns and cultural exchanges.[180] Historians further rely on evidence from various other fields belonging to the physical, biological, and social sciences as well as the humanities.[181]

In virtue of its relation to ideology and national identity, history is closely connected to politics and historical theories can directly impact political decisions. For example, irredentist attempts by one state to annex territory of another state often rely on historical theories claiming that the disputed territory belonged to the first state in the past.[182] History also plays a central role in so-called historical religions, which base some of their core doctrines on historical events. For instance, Christianity is often categorized as a historical religion because it is centred around historical events surrounding Jesus Christ.[183] History is relevant to many fields by studying their past, including the history of science, mathematics, philosophy, and art.[184]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Some authors restrict the term history to the factual series of past events and use the term historiography for the study of those events. Others use the term history for the study and representation of the past. They characterize historiography as a metatheory studying the methods and historical development of this academic discipline.[24]

- ^ Some theorists identify protohistory as a distinct period after prehistory that spans from the invention of writing to the first attempts to record history.[25]

- ^ Big History reaches back even further and starts with the Big Bang.[28]

- ^ There are disagreements about when exactly each period starts and ends. Alternative subdivisions may use overlapping or radically different time frames.[46]

- ^ New diseases and European military aggression and exploitation had severe consequences in the form of a drastic loss of life and cultural disruption among Indigenous communities in the Americas.[55]

- ^ Emphasizing the central relation between geography and history, Jules Michelet (1798–1874) wrote in his 1833 book Histoire de France, "without geographical basis, the people, the makers of history, seem to be walking on air".[60]

- ^ Understood in a narrow sense, the historical method is sometimes limited to the evaluation or criticism of sources.[118]

- ^ The exact definitions of primary source and secondary source are disputed and there is not always consensus on how a particular source should be categorized. For example, if a person was not present at a riot but reports on it shortly after it happened, some historians consider this report a primary source while others see it as a secondary source.[125]

- ^ Leopold von Ranke's (1795–1886) emphasis on source evaluation significantly influenced the practice of historical research.[128]

- ^ Historians consider the context and time of the document to understand the meanings of the terms it uses. For example, if a document uses the word awful, they have to decide whether it expresses the modern meaning 'terrible' or the historical meaning 'worthy of awe'.[130]

- ^ This becomes particularly challenging if different sources provide seemingly contradictory information.[132]

- ^ The creativity and imagination needed for this step is one of the reasons why some theorists understand history as an art rather than a science.[133]

- ^ For example, Martha Washington burned all private letters between her and her husband George Washington, leaving decades worth of silences on their relationship.[139] Another cause of silences, the existence of a taboo, such as a taboo against homosexuality, can have the effect that little information on the topic is recorded.[140]

- ^ Historical theory is a closely related term sometimes used as a synonym.[153]

- ^ Some philosophers have followed Francis Fukuyama (1952–present) in arguing that the "end of history" has already arrived based on the claim that the ideological evolution of humanity has reached its endpoint.[159]

Citations

- ^ Joseph & Janda 2008, p. 163

- ^ "History Definition". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ "What is History & Why Study It?". Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ a b Professor Richard J. Evans (2001). "The Two Faces of E.H. Carr". History in Focus, Issue 2: What is History?. University of London. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Professor Alun Munslow (2001). "What History Is". History in Focus, Issue 2: What is History?. University of London. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ^ Tosh, John (2006). The Pursuit of History (4th ed.). Pearson Education Limited. p. 52. ISBN 978-1405823517.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N.; Seixas, Peter Carr; Wineburg, Samuel S. (2000). Knowing, teaching, and learning history : national and international perspectives. Internet Archive. New York University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0814781418.

- ^ Nash l, Gary B. (2000). "The "Convergence" Paradigm in Studying Early American History in Schools". In Peter N. Stearns; Peters Seixas; Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. pp. 102–115. ISBN 0814781411.

- ^ "Prehistory Definition & Meaning". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Arnold 2000.

- ^ Seixas, Peter (2000). "Schweigen! die Kinder!". In Peter N. Stearns; Peters Seixas; Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0814781418.

- ^ Lowenthal, David (2000). "Dilemmas and Delights of Learning History". In Peter N. Stearns; Peters Seixas; Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0814781418.

- ^ Halsall, Paul. "Ancient History Sourcebook: 11th Brittanica: Herodotus". Internet History Sourcebooks Project. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ Vives, Juan Luis; Watson, Foster (1913). Vives, on education : a translation of the De tradendis disciplinis of Juan Luis Vives. Robarts – University of Toronto. Cambridge : The University Press.

- ^ Juan Luis Vives (1551). Ioannis Ludouici Viuis Valentini, De disciplinis libri 20. in tres tomos distincti, quorum ordinem versa pagella iudicabit. Cum indice copiosissimo (in Latin). National Central Library of Rome. apud Ioannem Frellonium.

- ^ Majoros, Sotirios (2019). All About Me: The Individual. FriesenPress. ISBN 978-1525558016. Archived from the original on 30 July 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ Tschannen, Rafiq (19 May 2013). "Ibn Khaldun: One of the Founding Fathers of Modern Historiography". The Muslim Times. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Thomas, Kelly (2018). "The History of Others: Foreign Peoples in Early Chinese Historiography". Institute for Advanced Study. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Chuku, Gloria (2013), Chuku, Gloria (ed.), "Kenneth Dike: The Father of Modern African Historiography", The Igbo Intellectual Tradition: Creative Conflict in African and African Diasporic Thought, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 137–164, doi:10.1057/9781137311290_6, ISBN 978-1-137-31129-0, retrieved 18 November 2024

- ^

- Kragh 1987, p. 41

- Little 2020, § 1. History and its representation

- Collingwood 2017, § 4. History and the Philosophy of History

- Ritter 1986, pp. 193–194

- ^

- Little 2020, § 1. History and its representation

- Tosh 2002, pp. 140–143

- ^

- Tucker 2011, pp. xii, 2

- Arnold 2000, p. 5

- Evans 2002, pp. 1–2

- Ritter 1986, pp. 193–194

- Tosh 2002, pp. 140–143

- ^

- Evans 2002, pp. 1–2

- Ritter 1986, p. 196

- ^

- Tucker 2011, pp. xii, 2

- Arnold 2000, p. 5

- ^ Kipfer 2000, pp. 457–458

- ^

- Woolf 2019, p. 300

- Renfrew 2008, p. 172

- ^

- Fagan & Durrani 2016, p. 4

- Ackermann et al. 2008, pp. xvii

- Stearns 2010, p. 17–18

- ^

- Bohan 2016, p. 10

- Dinwiddie 2016, p. 14–16

- ^

- Arnold 2000, pp. 114–115

- Parrott & Hake 1983, pp. 121–122

- Tosh 2002, pp. 50–52

- Ritter 1986, pp. 196–197

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 50–52

- Ritter 1986, pp. 196–197, 415–416

- ^

- Allchin 2004, pp. 179–180

- Välimäki & Aali 2020, p. 57

- ^

- Southgate 2005, p. xi–xii, 1, 57

- Tosh 2002, pp. 50–52

- ^

- Arnold 2000, p. 120–121

- Southgate 2005, p. 11–12, 57–58

- Tosh 2002, pp. 26, 50–52

- ^

- Arnold 2000, p. 121–122

- Tosh 2002, pp. 50–52

- ^

- Arnold 2000, p. 121

- Southgate 2005, pp. 38–39, 175–176

- Tosh 2002, pp. 50–51

- ^ Southgate 2005, p. xi–xii 49–51, 175–176

- ^

- Allchin 2004, pp. 179–180

- Välimäki & Aali 2020, p. 57

- ^

- Ritter 1986, pp. 193–195

- Stevenson 2010, p. 831

- HarperCollins 2022

- Joseph & Janda 2008, p. 163

- HarperCollins 2003, p. 99

- OED Staff 2024

- ^

- ^

- Joseph & Janda 2008, p. 163

- Hoad 1993, p. 217

- Cresswell 2021, § History

- OED Staff 2024

- ^ Ritter 1986, pp. 195–196

- ^

- Berkhofer 2022, pp. 10–11

- Tosh 2002, p. 141

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 108–109

- Lemon 1995, p. 112

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 34–35

- Veysey 1979, p. 1

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 78

- Christian 2008, pp. 97–99

- Jordanova 2000, p. 34

- ^

- Van Nieuwenhuyse 2020, p. 375

- Christian 2008, pp. 98–99

- Stearns 2001, Table of Contents

- Christian 2015, p. 7

- ^

- Christian 2015, pp. 5–7

- Northrup 2015, pp. 110–111

- ^

- Christian 2015, pp. 5–6

- Northrup 2015, pp. 110–111

- ^

- Cameron 1946, p. 171

- Arcodia & Basciano 2021, p. xv

- ^ Northrup 2015, p. 111

- ^

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, pp. 1, 10

- Stearns 2010, pp. 17–20

- Aldenderfer 2011, p. 4

- ^

- Christian 2015, p. 2

- Stearns 2010, pp. 17–20

- Wragg-Sykes 2016, pp. 195, 199, 211, 221

- ^

- Aldenderfer 2011, p. 1

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. v

- ^

- Stearns 2010, pp. 19–32

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 1–2, 89–90

- Ackermann et al. 2008, pp. xxix–xxxix

- ^

- Stearns 2010, pp. 33–36

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 193–194, 291–292

- ^

- Stearns 2010, p. 36

- Bulliet et al. 2015, p. 401

- ^

- Stearns 2010, pp. 36–39

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 401–402

- ^

- Stearns 2010, pp. 39–46

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 537–538, 677–678, 817–818

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 108–109

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 34, 46–47

- ^

- Diamond 1999, pp. 22, 25–32

- Darby 2002, p. 14

- Baker 2003, p. 23

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 34, 46–47

- ^ Darby 2002, p. 14

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 108–109

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 46–47

- ^

- Fisher 2014, p. 127

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. 12

- Stearns 2010, pp. 17–20

- ^

- Iliffe 2007, p. 5

- Stearns 2010, pp. 24–25

- ^ Asante 2024, p. 92

- ^

- Shillington 2018, pp. 93–94

- Iliffe 2007, pp. 2, 42–45

- ^

- Shillington 2018, p. 103

- Iliffe 2007, pp. 131–132

- ^ Iliffe 2007, pp. 193–195

- ^

- Shillington 2018, p. 417

- Iliffe 2007, pp. 242, 253, 260, 267–268

- ^

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. 15

- Headrick 2009, p. 6

- Wragg-Sykes 2016, p. 199

- ^

- Mason 2005, pp. 17–18

- Murphey & Stapleton 2019, pp. 10–13

- Cotterell 2011, p. xiii, 3–4

- AASA 2011, pp. 3–4

- Stearns 2010, pp. 24–25

- ^

- Cotterell 2011, p. xiii–xiv

- AASA 2011, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Cotterell 2011, p. 256–257

- Mason 2005, pp. 77–78

- ^

- Mason 2005, pp. 111–112, 167–168

- Murphey & Stapleton 2019, pp. 282–283

- Cotterell 2011, p. xvii–xviii

- Rana 2012, pp. 13–14

- ^

- Murphey & Stapleton 2019, p. 445

- Mason 2005, pp. 1

- Rana 2012, pp. 13–14

- ^ Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. 12

- ^ Roberts 1997, § The Importance of the Classical Past, § The Greeks, § An Attempt to Summarize

- ^

- Roberts 1997, § The Importance of the Classical Past, § The Rise of Roman Power, § Empire

- Black 2021, § What is Europe?

- ^

- Roberts 1997, § Decline and Fall in the West, § Christiandom

- Black 2021, § What is Europe?

- ^

- Roberts 1997, § Launching Modern History 1500–1800

- Stearns 2010, pp. 36–39

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 401–402

- ^

- Roberts 1997, § The European Age

- Stearns 2010, pp. 39–42

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 677–678

- ^

- Roberts 1997, § Europe's Twentieth Century: The Era of European Civil War

- Stearns 2010, p. 44

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 677–678

- ^

- Roberts 1997, § Europe in the Cold War and After, § European Integration

- Alcock 2002, p. 266–268

- Stearns 2010, pp. 39–46

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 677–678, 817–818

- ^

- Fisher 2014, p. 127

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. 12

- ^

- Ackermann et al. 2008, pp. xvii–xix

- Fernández-Armesto 2003, § Between Colonizations: The Americas' First 'Normalcy'

- Dorling Kindersley 2018, pp. 94–95

- ^

- Fernández-Armesto 2003, § Between Colonizations: The Americas' First 'Normalcy'

- Dorling Kindersley 2018, pp. 94–95

- ^

- Fernández-Armesto 2003, § Colonial Americas: Divergence and its Limits, § The Independence Era

- Stearns 2010, pp. 36–38

- Dorling Kindersley 2018, p. 95

- ^

- Fernández-Armesto 2003, § The Independence Era

- Raab & Rinke 2019, p. 20

- ^

- Fernández-Armesto 2003, § The American Century

- Bulliet et al. 2015, pp. 817–818

- ^

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. 12

- Lawson 2024, p. 57

- d'Arcy 2012, § Indigenous Exploration and Colonization of the Region

- ^

- Lawson 2024, p. 32, 57

- d'Arcy 2012, § Indigenous Exploration and Colonization of the Region

- ^

- Lawson 2024, p. 59–60, 85–86

- d'Arcy 2012, § The Intersection of European and Indigenous Worlds, § The Impact of Pre-Colonial European Influences, § European Settler Societies and Plantation Colonies

- ^

- d'Arcy 2012, § Times of Anxiety: World Wars, Pandemic, and Economic Depression, § Post-War Themes: The Nuclear Pacific, Decolonization, and the Search for Identity

- Lawson 2024, p. xii, 2, 96

- ^

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 34–35

- Yurdusev 2003, p. 24

- Tosh 2002, p. 109

- Gardiner 1988, pp. 1–3

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 109, 122

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 34–35

- Gardiner 1988, pp. 1–3

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 109–110

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 35–36

- ^ Tosh 2002, p. 110

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 112–113

- Watt et al. 1988, pp. 131–133

- ^

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 122–124

- Coleman et al. 1988, pp. 31–32

- ^

- Samuel et al. 1988, pp. 48–51

- Tosh 2002, pp. 125–127

- Stearns 2021

- ^

- Collinson et al. 1988, pp. 58–59

- Tosh 2002, pp. 101, 236–237, 286

- Burke 2019, § Introduction

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 272–273

- Collini et al. 1988, pp. 105–106, 109–110

- ^

- Santinello & Piaia 2010, pp. 487–488

- Verene 2008, pp. 6–8

- ^

- Porter et al. 1988, pp. 78–79

- Williams 2024, § Lead section

- ^ Potts et al. 1988, pp. 96–104

- ^ Hughes 2016, p. 1

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 101, 112–113, 124–125, 127, 129

- Yapp et al. 1988, pp. 155, 158

- Antonellos & Rantall 2017, p. 115

- Buchanan 2024, Lead section

- Ramsay 2008, p. 283

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 244–245

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 81, 92–93

- Zaagsma 2023, § Introduction

- Jordanova 2000, pp. 49–50

- ^ Wong 2005, pp. 416–417

- ^

- ^

- Zhao 2023, pp. 9–10

- Birke, Butter & Köppe 2011, p. 7

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 13–14, 113–114

- Tosh 2002, pp. 27, 224–225, 238

- Veysey 1979, p. 1

- ^ Bohan 2016, p. 10

- ^

- Christian 2015, p. 3

- Stearns 2010, pp. 11–13, 17–20

- ^

- Bod 2013, p. 260

- O'Hara 2019, p. 176

- ^ Tosh 2002, pp. 113–115

- ^

- Glassberg 1996, pp. 7–8

- Tosh 2002, pp. xiv–xv

- ^ Ritter 1986, p. 268

- ^

- Fazal 2023, p. 140

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 1–2

- Ahlskog 2020, pp. 1–2

- Kamp et al. 2020, pp. 9–10

- Ritter 1986, p. 268

- ^ Kamp et al. 2020, pp. 19–20

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 35

- Tosh 2002, pp. 57–58

- Ritter 1986, pp. 143–144

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 36

- Tosh 2002, pp. 54–58

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 37

- Tosh 2002, pp. 57–58

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 37

- Tosh 2002, pp. 57–59

- ^ Tosh 2002, p. 57

- ^ Tosh 2002, pp. 56–57

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 40–45

- Arnold 2000, p. 59–60

- Tosh 2002, p. 56

- ^ Tosh 2002, pp. 87

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, pp. 70–71

- Garraghan 1946, pp. 168–169

- Tosh 2002, pp. 59, 87–88

- Topolski 2012, p. 432

- Ritter 1986, pp. 84–86

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 90–91

- Gil & Marsen 2022, p. 24

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, pp. 70–71

- Garraghan 1946, pp. 168–169

- Tosh 2002, pp. 59, 87–88, 91–92

- Topolski 2012, p. 432

- Ritter 1986, pp. 84–86

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 140, 171

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, p. 71

- ^ Tosh 2002, p. 141

- ^

- Berkhofer 2008, pp. 49–50

- Tosh 2002, pp. 139–143

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 142–143

- Little 2020, § 1. History and its representation

- ^ Tosh 2002, p. 140

- ^

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 78

- Lucas 2004, pp. 50–51

- Christian 2015, pp. 5–6

- ^ Kamp et al. 2020, pp. 77–78

- ^ Oberg 2019, p. 17

- ^ Kamp et al. 2020, pp. 77–78

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 244–245

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 81, 92–93

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 13–14, 88

- Berkhofer 2008, pp. 49–50

- Lloyd 2011, pp. 371–372

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 13

- Tosh 2002, pp. 166, 185

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 22, 185

- Berkhofer 2008, pp. 45, 78

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 13–14

- Tosh 2002, pp. 27, 224–225

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 110–111

- Tosh 2002, pp. 121, 133

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 113–114

- Tosh 2002, p. 238

- ^

- Woolf 2019, pp. 3

- Tucker 2011, pp. xii, 2

- Ritter 1986, pp. 188–189

- Little 2020, § 4. Historiography and the Philosophy of History

- ^

- Little 2020, § 4. Historiography and the Philosophy of History

- Lloyd 2011, p. 371, 374

- ^

- Little 2020, § 4. Historiography and the Philosophy of History

- Cheng 2012, pp. 1–2

- ^

- Howell & Prevenier 2001, pp. 110–111

- Tosh 2002, pp. 121, 133

- Little 2020, § 4. Historiography and the Philosophy of History

- ^

- Little 2020, § 4. Historiography and the Philosophy of History

- Bentley 2006, pp. xi, xv

- Cheng 2012, pp. 1–2

- ^ Paul 2015, pp. xv, 2–3, 12–13

- ^

- Carr 2006, Lead section

- Jensen, Lead section

- Little 2020, Lead section, § 1. History and its representation

- Paul 2015, pp. 10

- ^

- Little 2020, Lead section, § 1. History and its representation

- Paul 2015, pp. 10

- ^

- Stanford 1998, p. 85–87

- Little 2020, § 3.3 Causation in history

- ^

- Carr 2006, § 2. "Critical" Philosophy of History: Philosophical Reflection on Historical Knowledge

- Little 2020, § 3.1 General laws in history?, § 3.3 Causation in history

- ^

- Little 2020, § 2.2 Does history possess directionality?

- Stanford 1998, p. 74–75

- Paul 2015, pp. 10

- ^

- Lemon 2003, pp. 390–391

- Jackson & Xidias 2017, p. 21

- ^

- Little 2020, § 3.2 Historical objectivity

- Carr 2006, § 2. "Critical" Philosophy of History: Philosophical Reflection on Historical Knowledge

- Stanford 1998, p. 50–53

- Paul 2015, pp. 10

- ^

- Little 2020, § 4. Historiography and the philosophy of history

- Heller 2016, § 14. The Specificity of Philosophy of History

- ^

- Lemon 2003, p. 125

- Stanford 1998, p. 155

- Carr 2006, § 4. Historicity, Historicism and the Historicization of Philosophy

- Vision 2023, § VI Truth Epistemologized: 6. Historicism

- ^ Metzger & Harris 2018, p. 2

- ^

- Hughes, Cox & Godard 2013, pp. 4–5, 10–11

- Metzger & Harris 2018, p. 3

- Levstik & Thornton 2018, pp. 476–477

- Cooper 1995, pp. 3–4

- ^

- Levstik & Thornton 2018, pp. 477

- Cooper 1995, pp. 110–112

- ^

- Sharp et al. 2021, p. 66–67, 71

- Hunt 2006, p. 49

- Phillips 2008, pp. 34, 48–50

- ^

- van Hover & Hicks 2018, pp. 407–408

- Metzger & Harris 2018, p. 6–7

- Hunt 2006, p. 36

- Grant 2018, pp. 422–428

- ^

- Metzger & Harris 2018, p. 6

- Cooper 1995, p. 2

- ^

- Metzger & Harris 2018, p. 3, 6–7

- Sharp et al. 2021, p. 49

- Hunt 2006, pp. 6–7

- ^

- Sharp et al. 2021, p. 49

- Zajda 2015, pp. 5–6

- ^

- Girard & Harris 2018, p. 258

- Schneider 2008, pp. 107–108

- ^

- Stoddard 2018, pp. 631–632

- Clark & Grever 2018, p. 181

- ^

- Clark & Grever 2018, p. 181, 184

- Korte & Paletschek 2014, pp. 7–8

- ^

- ^

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. v

- Kamp et al. 2020, p. 36

- Tosh 2002, p. 55

- Manning 2020, pp. 1–2

- Norberg & Deutsch 2023, p. 15

- Aldenderfer 2011, p. 1

- ^

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. v, 1, 15

- Tosh 2002, pp. 11, 55

- ^ Manning 2020, pp. 2–3

- ^

- ^

- Tuniz & Vipraio 2016, p. v, 1, 11, 19

- Tosh 2002, pp. 34, 205

- ^

- Tosh 2002, pp. 90, 186–187

- Lewis 2012, § The Disciplines of Space and Time

- ^ Manning 2020, p. 3

- ^

- Southgate 2005, p. xi, 21

- Arnold 2000, p. 121

- White & Millett 2019, p. 419

- ^

- Wiles 1978, pp. 4–6

- Johnson 2024, § 10. Historiography and History

- Law 2012, p. 1

- ^

- Porter et al. 1988, pp. 78–79

- Verene 2008, pp. 6–8

- Potts et al. 1988, pp. 96–104

Sources

- AASA (2011). Towards a Sustainable Asia: the Cultural Perspectives. Science Press Beijing and Springer. ISBN 978-7-03-029011-3.

- Abrams, Lynn (2016). Oral History Theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-27798-9.

- Ackermann, Marsha E.; Schroeder, Michael J.; Terry, Janice J.; Upshur, Jiu-Hwa Lo; Whitters, Mark F., eds. (2008). Encyclopedia of World History 1: The Ancient World Prehistoric Eras to 600 c.e. Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6386-4.

- Ahlskog, Jonas (2020). The Primacy of Method in Historical Research: Philosophy of History and the Perspective of Meaning. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-28524-6.

- Alcock, A. (2002). A Short History of Europe: From the Greeks and Romans to the Present Day. Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-230-59742-6.

- Aldenderfer, Mark (2011). "Era 1: Beginnings of Human Society to 4000 BCE". World History Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85109-930-6.

- Allchin, Douglas (2004). "Pseudohistory and Pseudoscience". Science & Education. 13 (3): 179–195. Bibcode:2004Sc&Ed..13..179A. doi:10.1023/B:SCED.0000025563.35883.e9.

- Antonellos, Steven; Rantall, Jayne (2017). "Indigenous History: A Conversation". Australasian Journal of American Studies. 36 (2): 115–128. ISSN 1838-9554. JSTOR 26532936.

- Arcodia, Giorgio Francesco; Basciano, Bianca (2021). "Periodization of Chinese History". Chinese Linguistics: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884783-0.

- Arnold, John (2000). History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285352-3.

- Asante, Molefi Kete (2024). The History of Africa: The Quest for Eternal Harmony (4 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-81615-7.

- Baker, Alan R. H. (2003). Geography and History: Bridging the Divide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28885-9.

- Bentley, Michael (2006). "General Introduction: The Project of Historiography". In Bentley, Michael (ed.). Companion to Historiography. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-97023-0.

- Berkhofer, R. (2008). Fashioning History: Current Practices and Principles. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-61720-9.

- Berkhofer, Robert F. (2022). Forgeries and Historical Writing in England, France, and Flanders, 900-1200. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-78327-691-2.

- Birke, Dorothee; Butter, Michael; Köppe, Tilmann (2011). "Introduction". Counterfactual Thinking - Counterfactual Writing. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-026866-9.

- Black, Jeremy (2021). A History of Europe: From Pre-History to the 21st Century. Arcturus Publishing. ISBN 978-1-3988-0986-4.

- Bod, Rens (2013). A New History of the Humanities: The Search for Principles and Patterns from Antiquity to the Present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966521-1.

- Bohan, Elise (2016). "Introduction". Big History: Our Incredible Journey, from Big Bang to Now. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-241-22590-5. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- Buchanan, Robert Angus (2024). "History of Technology". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 November 2024.

- Bulliet, Richard; Crossley, Pamela; Headrick, Daniel; Hirsch, Steven; Johnson, Lyman; Northrup, David (2015). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Vol. 1 (6th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-44567-0. Archived from the original on 29 April 2024. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- Burke, Peter (2019). What is Cultural History?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-5095-2224-8.

- Cameron, Meribeth E. (1946). "The Periodization of Chinese History". Pacific Historical Review. 15 (2): 171–177. doi:10.2307/3634927. JSTOR 3634927.

- Carr, David (2006). "Philosophy of History". In Borchert, Donald M. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 7: Oakeshott - Presupposition (2 ed.). Thomson Gale, Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-865787-5.

- Cheng, Eileen Ka-May (2012). Historiography: An Introductory Guide. Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-7767-4.

- Christian, David (2008). This Fleeting World: A Short History of Humanity. Berkshire Publishing. ISBN 978-1-933782-04-1.

- Christian, David (2015). "Introduction and Overview". In Christian, David (ed.). The Cambridge World History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76333-2.

- Clark, Anna; Grever, Maria (2018). "7. Historical Consciousness". In Metzger, Scott Alan; Harris, Lauren McArthur (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch7. ISBN 978-1-119-10081-2.

- Coleman, D. C.; Floud, Roderick; Barker, T. C.; Daunton, M. J.; Crafts, N. F. R. (1988). "What is Economic History … ?". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_4. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Collingwood, R. G. (2017). "The Nature and Aims of a Philosophy of History". Essays in the Philosophy of History. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-5287-6685-2.

- Collini, Stefan; Skinner, Quentin; Hollinger, David A.; Pocock, J. G. A.; Hunter, Michael (1988). "What is Intellectual History … ?". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_10. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Collinson, Patrick; Brooke, Christopher; Norman, Edward; Lake, Peter; Hempton, David (1988). "What is Religious History … ?". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_6. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Cooper, Hilary (1995). History in the Early Years. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10100-4.

- Cotterell, Arthur (2011). Asia: A Concise History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-82959-2.

- Cresswell, Julia (2021). Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-886875-0.

- d'Arcy, Paul (2012). "30. Oceania and Australasia". In Bentley, Jerry H. (ed.). Oxford Handbook of World History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199235810.013.0031. ISBN 978-0-19-923581-0.

- Darby, Henry Clifford (2002). The Relations of History and Geography: Studies in England, France and the United States. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-699-3.

- Diamond, Jared (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06922-8.

- Dinwiddie, Robert (2016). "Threshold 1". Big History: Our Incredible Journey, from Big Bang to Now. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-241-22590-5. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- Dorling Kindersley (2018). Timelines of Everything: From woolly mammoths to world wars. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 978-0-241-42807-8.

- Evans, Richard J. (2002). "1. Prologue: What is History? – Now". In Cannadine, D. (ed.). What is History Now?. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-20452-2.

- Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2016). World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-27910-5.

- Fazal, Tanweer (2023). "'Documents of Power': Historical Method and the Study of Politics". Studies in Indian Politics. 11 (1): 140–149. doi:10.1177/23210230231166179.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2003). The Americas: A Hemispheric History. Random House. ISBN 978-1-58836-302-2.

- Fisher, Michael H. (2014). Migration: A World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976434-1.

- Gardiner, Juliet (1988). "Introduction". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_1. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Garraghan, Gilbert J. (1946). Delanglez, Jean (ed.). A Guide to Historical Method. Fordham University Press. OCLC 7545487.

- Gil, Jeffrey; Marsen, Sky (2022). Exploring Language in Global Contexts. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-59387-7.

- Girard, Brian; Harris, Lauren McArthur (2018). "10. Global and World History Education". In Metzger, Scott Alan; Harris, Lauren McArthur (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch10. ISBN 978-1-119-10081-2.

- Glassberg, David (1996). "Public History and the Study of Memory". The Public Historian. 18 (2): 7–23. doi:10.2307/3377910. JSTOR 3377910.

- Grant, S. G. (2018). "16. Teaching Practices in History Education". In Metzger, Scott Alan; Harris, Lauren McArthur (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 419–448. doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch16. ISBN 978-1-119-10081-2.

- HarperCollins (2003). Collins Latin Concise Dictionary. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-053690-9.

- HarperCollins (2022). "History". American Heritage Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

- Headrick, Daniel R. (2009). Technology: A World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971366-0.

- Heller, Agnes (2016). A Theory of History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-26882-6.

- Hoad, T. F. (1993). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283098-8.

- Howard, Michael; Bond, Brian; Stagg, J. C. A.; Chandler, David; Best, Geoffrey; Terrine, John (1988). "What is Military History … ?". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_2. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Howell, Martha C.; Prevenier, Walter (2001). From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8560-2.

- Hughes, J. Donald (2016). What is Environmental History?. Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-8844-2.

- Hughes, Pat; Cox, Kath; Godard, Gillian (2013). Primary History Curriculum Guide. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-12742-9.

- Hunt, Martin (2006). "2. Why Learn History?". A Practical Guide to Teaching History in the Secondary School. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-19967-9.

- Iliffe, John (2007). Africans: The History of a Continent (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86438-1.

- Jackson, Ian; Xidias, Jason (2017). An Analysis of Francis Fukuyama's The End of History and the Last Man. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-35127-0.

- Jensen, Anthony K. "History, Philosophy of". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- Johnson, Peter (2024). R.G. Collingwood and Christianity: Faith, Philosophy and Politics. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-46543-5.

- Jordanova, Ludmilla (2000). History in Practice. Arnold Publishers. ISBN 0-340-66331-6.

- Joseph, Brian; Janda, Richard (2008). "On Language, Change, and Language Change - Or, Of History, Linguistics, and Historical Linguistics". In Joseph, Brian; Janda, Richard (eds.). The Handbook of Historical Linguistics. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-75633-1.

- Kamp, Jeannette; Legêne, Susan; Rossum, Matthias van; Rümke, Sebas (2020). Writing History!: A Companion for Historians. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-485-3762-4.

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-306-46158-3.

- Korte, Barbara; Paletschek, Sylvia (2014). "Introduction". In Korte, Barbara; Paletschek, Sylvia (eds.). Popular History Now and Then: International Perspectives. transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8394-2007-2.

- Kragh, Helge (1987). An Introduction to the Historiography of Science. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38921-1.

- Law, David R. (2012). The Historical-Critical Method: A Guide for the Perplexed. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-40012-3.

- Lawson, Stephanie (2024). Regional Politics in Oceania: From Colonialism and Cold War to the Pacific Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-42758-6.

- Leavy, Patricia (2011). Oral History: Understanding Qualitative Research. Oxford Univerity Press. ISBN 978-0-19-539509-9.

- Lemon, Michael C. (1995). The Discipline of History and the History of Thought. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12346-1.

- Lemon, M. C. (2003). Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-71746-0.

- Levstik, Linda S.; Thornton, Stephen J. (2018). "Reconceptualizing History for Early Childhood Through Early Adolescence". In Metzger, Scott Alan; Harris, Lauren McArthur (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch18. ISBN 978-1-119-10081-2.

- Lewis, Martin W. (2012). Bentley, Jerry H. (ed.). Geographies. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199235810.

- Little, Daniel (2020). "Philosophy of History". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- Lloyd, Christopher (2011). "Historiographic Schools". In Tucker, Aviezer (ed.). A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5152-1.

- Lucas, Gavin (2004). The Archaeology of Time. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-38427-3.

- Manning, Patrick (2020). Methods for Human History: Studying Social, Cultural, and Biological Evolution. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-53882-8.

- Mason, Colin (2005). A Short History of Asia (2 ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-3611-0.

- Metzger, Scott Alan; Harris, Lauren McArthur (2018). "Introduction". In Metzger, Scott Alan; Harris, Lauren McArthur (eds.). The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch0. ISBN 978-1-119-10081-2.

- Miller, Bruce Granville (2024). Oral History on Trial: Recognizing Aboriginal Narratives in the Courts. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2073-8.

- Morillo, Stephen (2017). What is Military History?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-5095-1764-0.

- Murphey, Rhoads; Stapleton, Kristin (2019). A History of Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-23189-3.

- Norberg, Matilda Baraibar; Deutsch, Lisa (2023). The Soybean Through World History: Lessons for Sustainable Agrofood Systems. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-90347-8.

- Northrup, David R. (2015). "From Divergence to Convergence: Centrifugal and Centripetal Forces in History". In Christian, David (ed.). The Cambridge World History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76333-2.

- O'Hara, Phillip Anthony (2019). "History of Institutional Economics". In Sinha, Ajit; Thomas, Alex M. (eds.). Pluralistic Economics and Its History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-00183-9.

- Oberg, Barbara B. (2019). Women in the American Revolution: Gender, Politics, and the Domestic World. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-4260-5.

- OED Staff (2024). "History, n". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/9602520444.

- Parrott, Linda J.; Hake, Don F. (1983). "Toward a Science of History". The Behavior Analyst. 6 (2): 121–132. doi:10.1007/BF03392391. PMC 2741978. PMID 22478582.

- Paul, Herman (2015). Key issues in historical theory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-80272-8.

- Phillips, Ian (2008). Teaching History: Developing as a Reflective Secondary Teacher. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4462-4538-5.

- Porter, Roy; Shapin, Steven; Schaffer, Simon; Young, Robert M.; Cooter, Roger; Crosland, Maurice (1988). "What is the History of Science … ?". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_7. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Potts, Alex; House, John; Hope, Charles; Gretton, Tom (1988). "What is the History of Art … ?". What is History Today … ?. Macmillan Education UK. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_9. ISBN 978-1-349-19161-1.

- Raab, Josef; Rinke, Stefan (2019). "Introduction: History and Society in the Americas from the 16th to the 19th Century. The Big Picure". In Kaltmeier, Olaf; Raab, Josef; Foley, Mike; Nash, Alice; Rinke, Stefan; Rufer, Mario (eds.). The Routledge Handbook to the History and Society of the Americas. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-13869-7.

- Ramsay, John G. (2008). "Education, History of". In Provenzo, Eugene F. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Social and Cultural Foundations of Education. Sage. ISBN 978-1-4522-6597-1. Retrieved 3 May 2023.