Arctic Council

| |

| |

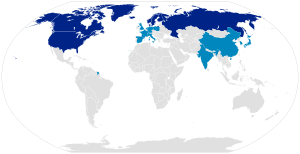

members observers | |

| Formation | September 19, 1996 (Ottawa Declaration) |

|---|---|

| Type | Intergovernmental organization |

| Purpose | Forum for promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states, with the involvement of the Arctic Indigenous communities |

| Headquarters | Tromsø, Norway (since 2012) |

| Membership | 8 member countries

13 observer countries

|

Main organ | Secretariat |

| Website | arctic-council.org |

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| United Nations initiatives |

| International Treaties |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Countries |

| Category |

The Arctic Council is a high-level intergovernmental forum that addresses issues faced by the Arctic governments and the indigenous people of the Arcticregion. At present, eight countries exercise sovereignty over the lands within the Arctic Circle, and these constitute the member states of the council: Canada; Denmark; Finland; Iceland; Norway; Russia; Sweden; and the United States. Other countries or national groups can be admitted as observer states, while organizations representing the concerns of indigenous peoples can be admitted as indigenous permanent participants.[1]

History

[edit]The first step towards the formation of the Council occurred in 1991 when the eight Arctic countries signed the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). The 1996 Ottawa Declaration[2] established the Arctic Council[3] as a forum for promoting cooperation, coordination, and interaction among the Arctic states, with the involvement of the Arctic Indigenous communities and other Arctic inhabitants on issues such as sustainable development and environmental protection.[4][5] The Arctic Council has conducted studies on climate change, oil and gas, and Arctic shipping.[1][5][6][7]

In 2011, the Council member states concluded the Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement, the first binding treaty concluded under the council's auspices.[5][8]

On March 3, 2022, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the United States declared that they will not attend meetings of the Arctic Council under Russian chairmanship because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[9][10] The same countries issued a second statement on June 8, 2022 that declared their intent to resume cooperation on a limited number of previously approved Arctic Council projects that do not involve Russian leadership or participation.[11][12]

Membership and participation

[edit]The council is made up of member and observer states, Indigenous permanent participants , and observer organizations.[1]

Members

[edit]Only states with territory in the Arctic can be members of the council. The member states consist of the following:[1]

- Canada

- Denmark

- Finland

- Iceland

- Norway

- Russia

- Sweden

- United States

Observers

[edit]Observer status is open to non-Arctic states approved by the Council at the Ministerial Meetings that occur once every two years. Observers have no voting rights in the council. As of September 2021, thirteen non-Arctic states have observer status.[13] Observer states receive invitations for most Council meetings. Their participation in projects and task forces within the working groups is not always possible, but this poses few problems as few observer states want to participate at such a detailed level.[5][14]

As of 2021[update], observer states included:[13]

- Germany, 1998

- Netherlands, 1998

- Poland, 1998

- United Kingdom, 1998

- France, 2000

- Spain, 2006

- China, 2013

- India, 2013

- Italy, 2013

- Japan, 2013

- South Korea, 2013

- Singapore, 2013

- Switzerland, 2017

In 2011, the Council clarified its criteria for admission of observers, most notably including a requirement of applicants to "recognize Arctic States' sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction in the Arctic" and "recognize that an extensive legal framework applies to the Arctic Ocean including, notably, the Law of the Sea, and that this framework provides a solid foundation for responsible management of this ocean".[5]

Pending observer status

[edit]Pending observer states need to request permission for their presence at each individual meeting; such requests are routine and most of them are granted. At the 2013 Ministerial Meeting in Kiruna, Sweden — the European Union (EU) requested full observer status. It was not granted, mostly because the members do not agree with the EU ban on hunting seals.[15] Although the European Union has a specific Arctic policy and is active in the region, the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine prevents it from reconsidering its status within the Arctic Council.[16]

The role of observers was re-evaluated, as were the criteria for admission. As a result, the distinction between permanent and ad hoc observers were dropped.[15]

Future observer status

[edit]In 2023, Brazil expressed its interest in joining the Arctic Council as the first non-Arctic Latin American observer.[17]

Indigenous permanent participants

[edit]Seven of the eight-member states, excluding Iceland, have indigenous communities living in their Arctic areas. Organizations of Arctic Indigenous Peoples can obtain the status of Permanent Participant to the Arctic Council,[5] but only if they represent either one indigenous group residing in more than one Arctic State, or two or more Arctic indigenous peoples groups in a single Arctic state. The number of Permanent Participants should at any time be less than the number of members. The category of Permanent Participants has been created to provide for active participation and full consultation with the Arctic indigenous representatives within the Arctic Council. This principle applies to all meetings and activities of the Arctic Council.[citation needed]

Permanent Participants may address the meetings. They may raise points of order that require an immediate decision by the chairman. Agendas of Ministerial Meetings need to be consulted beforehand with them; they may propose supplementary agenda items. When calling the biannual meetings of Senior Arctic Officials, the Permanent Participants must have been consulted beforehand. Moreover, though only states have a right to vote in the Arctic Council the permanent participants must, according to the Ottawa Declaration be fully consulted, which is close to de facto power of veto should they all reject a particular proposal.[18] This mandatory consultation process matches the consultation and free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) requirement mentioned in the United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Finally, Permanent Participants may propose cooperative activities, such as projects. All this makes the position of Arctic indigenous peoples within the Arctic Council quite influential compared to the (often marginal) role of such peoples in other international governmental fora. The status of permanent participant is indeed unique and enables circumpolar peoples to be seated at the same table as states' delegations while in any other international organization it is not the case. Nevertheless, decision-making in the Arctic Council remains in the hands of the eight-member states, on the basis of consensus.[citation needed]

As of 2023, six Arctic indigenous communities have Permanent Participant status.[5] These groups are represented by

- The Aleut International Association (AIA), representing more than 15,000 Aleuts in Russia and the United States (Alaska).[19]

- The Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC), representing 45,000 Athabaskan peoples in Canada (Northwest Territories and Yukon) and the United States (Alaska).[20]

- The Gwich'in Council International (GCI), representing 9,000 Gwichʼin people in Canada (Northwest Territories and Yukon) and the United States (Alaska).[21]

- The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), representing 180,000 Inuit in Canada (Inuit Nunangat), Greenland, Russia (Chukotka) and the United States (Alaska).[22]

- The Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON), representing 250,000 Indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East.[23]

- The Saami Council, representing more than 100,000 Sámi of Finland, Norway, Russia and Sweden.[24]

However prominent the role of indigenous peoples, the Permanent Participant status does not confer any legal recognition as peoples. The Ottawa Declaration, the Arctic Council's founding document, explicitly states (in a footnote):

"The use of the term 'peoples' in this declaration shall not be construed as having any implications as regard the rights which may attach to the term under international law."[citation needed]

The Indigenous Permanent Participants are assisted by the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples Secretariat.[1]

Observer organizations

[edit]Approved intergovernmental organizations and Inter-parliamentary institutions (both global and regional), as well as non-governmental organizations can also obtain Observer Status.[13]

Organizations with observer status currently include the Arctic Parliamentarians,[25] International Union for Conservation of Nature, the International Red Cross Federation, the Nordic Council, the Northern Forum,[26] United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Environment Programme; the Association of World Reindeer Herders,[27] Oceana,[28] the University of the Arctic, and the World Wide Fund for Nature-Arctic Programme.[citation needed]

Administrative aspects

[edit]

Meetings

[edit]The Arctic Council convenes every six months somewhere in the Chair's country for a Senior Arctic Officials (SAO) meeting. SAOs are high-level representatives from the eight-member nations. Sometimes they are ambassadors, but often they are senior foreign ministry officials entrusted with staff-level coordination. Representatives of the six Permanent Participants and the official Observers also are in attendance.[citation needed]

At the end of the two-year cycle, the Chair hosts a Ministerial-level meeting, which is the culmination of the council's work for that period. Most of the eight-member nations are represented by a Minister from their Foreign Affairs, Northern Affairs, or Environment Ministry.[citation needed]

A formal, although non-binding declaration, named for the town in which the meeting is held, sums up the past accomplishments and the future work of the council. These declarations cover climate change, sustainable development, Arctic monitoring and assessment, persistent organic pollutants and other contaminants, and the work of the council's five Working Groups.[citation needed]

Arctic Council members agreed to action points on protecting the Arctic but most have never materialized.[29]

| Date(s) | City | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 17–18 September 1998 | Iqaluit | Canada |

| 13 October 2000 | Barrow | United States |

| 10 October 2002 | Inari | Finland |

| 24 November 2004 | Reykjavík | Iceland |

| 26 October 2006 | Salekhard | Russia |

| 29 April 2009 | Tromsø | Norway |

| 12 May 2011 | Nuuk | Greenland, Denmark |

| 15 May 2013 | Kiruna | Sweden |

| 24 April 2015 | Iqaluit | Canada |

| 10–11 May 2017 | Fairbanks | United States |

| 7 May 2019 | Rovaniemi | Finland |

| 19–20 May 2021 | Reykjavík | Iceland |

| 11 May 2023 | Salekhard | Russia[30] |

Chairmanship

[edit]Chairmanship of the Council rotates every two years.[31] The current chair is Norway, which serves until the Ministerial meeting in 2025.[32]

- Canada (1996–1998)[33]

- United States (1998–2000)[34]

- Finland (2000–2002)[35]

- Iceland (2002–2004)[35]

- Russia (2004–2006)[35]

- Norway (2006–2009)[35]

- Denmark (2009–2011)[35][36]

- Sweden (2011–2013)[31][37]

- Canada (2013–2015)[38]

- United States (2015–2017)[34]

- Finland (2017–2019)[39][40]

- Iceland (2019–2021)

- Russia (2021–2023)

- Norway (2023-2025)[41]

Norway, Denmark, and Sweden have agreed on a set of common priorities for the three chairmanships. They also agreed to a shared secretariat 2006–2013.[35]

The secretariat

[edit]Each rotating Chair nation accepts responsibility for maintaining the secretariat, which handles the administrative aspects of the council, including organizing semiannual meetings, hosting the website, and distributing reports and documents. The Norwegian Polar Institute hosted the Arctic Council Secretariat for the six-year period from 2007 to 2013; this was based on an agreement between the three successive Scandinavian Chairs, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden. This temporary Secretariat had a staff of three.[citation needed]

In 2012, the Council moved towards creating a permanent secretariat in Tromsø, Norway.[5][42]

Past directors

[edit]- Magnús Jóhannesson (Iceland) February 2013-October 2017[43]

- Nina Buvang Vaaja (Norway) October 2017-August 2021[44]

- Mathieu Parker (Canada) August 2021 – Present

The Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat

[edit]It is costly for the Permanent participants to be represented at every Council meeting, especially since they take place across the entire circumpolar realm. To enhance the capacity of the PPs to pursue the objectives of the Arctic Council and to assist them to develop their internal capacity to participate and intervene in Council meetings, the Council provides financial support to the Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat (IPS).[45]

The IPS board decides on the allocation of the funds. The IPS was established in 1994 under the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). It was based in Copenhagen until 2016 when it relocated to Tromsø.[citation needed]

In September 2017, Anna Degteva replaced Elle Merete Omma as the executive secretary for the Indigenous Peoples´ Secretariat.[46]

Working groups, programs and action plans

[edit]Arctic Council working groups document Arctic problems and challenges such as sea ice loss, glacier melting, tundra thawing, increase of mercury in food chains, and ocean acidification affecting the entire marine ecosystem.[citation needed]

Arctic Council working groups

[edit]- Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme[47] (AMAP)

- Conservation of Arctic Flora & Fauna[48] (CAFF)

- Emergency Prevention, Preparedness & Response[49] (EPPR)

- Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment[50][51] (PAME)

- Sustainable Development Working Group[52] (SDWG)

- Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP) (since 2006)[53]

Programs and action plans

[edit]- Arctic Biodiversity Assessment[54]

- Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP)

- Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

- Arctic Human Development Report

Security and geopolitical issues

[edit]Before signing the Ottawa Declaration, a footnote was added stating; "The Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security".[55] In 2019, United States Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stated that circumstances had changed and "the region has become an arena for power and for competition. And the eight Arctic states must adapt to this new future".[56] The council is often in the middle of security and geopolitical issues since the Arctic has peculiar interests to Member States and Observers. Changes in the Arctic environment and participants of the Arctic Council have led to a reconsideration of the relationship between geopolitical matters and the role of the Arctic Council.[citation needed]

Disputes over land and ocean in the Arctic had been extremely limited. The only outstanding land dispute was between Canada and Denmark, the Whisky War, over Hans Island, which was resolved in the summer of 2022 with agreement to split the island in half.[57] There are oceanic claims between the United States and Canada in the Beaufort Sea.[58][59]

The major territorial disputes are over exclusive rights to the seabed under the central Arctic high seas. Due to climate change and melting of the Arctic sea-ice, more energy resources and waterways are now becoming accessible. Large reserves of oil, gas and minerals are located within the Arctic. This environmental factor generated territorial disputes among member states. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea allows states to extend their exclusive right to exploit resources on and in the continental shelf if they can prove that seabed more than 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) from baselines is a natural prolongation of the land. Canada, Russia, and Denmark (via Greenland) have all submitted partially overlapping claims to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), which is charged with confirming the continental shelf's outer limits. Once the CLCS makes its rulings, Russia, Denmark, and Canada will need to negotiate to divide their overlapping claims.[60]

Disputes also exist over the nature of the Northwest Passage and the Northeast Passage / Northern Sea Route. Canada claims the entire Northwest Passage are Canadian Internal Waters, which means Canada would have total control over which ships may enter the channel. The United States believes the Passage is an international strait, which would mean any ship could transit at any time, and Canada could not close the Passage. Russia's claims over the Northern Sea Route are significantly different. Russia only claims small segments of the Northern Sea Route around straits as internal waters. However, Russia requires all commercial vessels to request and obtain permission to navigate in a large area of the Russian Arctic exclusive economic zone under Article 234 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which grants coastal states greater powers over ice-covered waters.

Canadian sovereignty over the Northwest Passage arouses substantial public concern in Canada. A poll indicated that half of Canadian respondents said Canada should try to assert its full sovereignty rights over the Beaufort Sea compared to just 10 percent of Americans.[61] New commercial trans-Arctic shipping routes can be another factor of conflicts. A poll found that Canadians perceive the Northwest Passage as their internal Canadian waterway whereas other countries assert it is an international waterway.[61]

The increase in the number of observer states drew attention to other national security issues. Observers have demonstrated their interests in the Arctic region. China has explicitly shown its desire to extract natural resources in Greenland.[62]

Military infrastructure is another point to consider. Canada, Denmark, Norway and Russia are rapidly increasing their defence presence by building up their militaries in the Arctic and developing their building infrastructure.[63]

However, some say that the Arctic Council facilitates stability despite possible conflicts among member states.[5] Norwegian Admiral Haakon Bruun-Hanssen has suggested that the Arctic is "probably the most stable area in the world". They say that laws are well established and followed.[62] Member states think that the sharing cost of the development of Arctic shipping-lanes, research, etc., by cooperation and good relationships between states is beneficial to all.[64]

Looking at these two different perspectives, some suggest that the Arctic Council should expand its role by including peace and security issues as its agenda. A 2010 survey showed that large majorities of respondents in Norway, Canada, Finland, Iceland, and Denmark were very supportive on the issues of an Arctic nuclear-weapons free zone.[65] Although only a small majority of Russian respondents supported such measures, more than 80 percent of them agreed that the Arctic Council should cover peace-building issues.[66] Paul Berkman suggests that solving security matters in the Arctic Council could save members the much larger amount of time required to reach a decision in United Nations. However, as of June 2014, military security matters are often avoided.[67] The focus on science and resource protection and management is seen as a priority, which could be diluted or strained by the discussion of geopolitical security issues.[68]

Reactions to Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

[edit]The Arctic Council faced an unprecedented challenge in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In response, the Council’s seven other member states condemned the invasion, halting cooperative projects involving Russia and effectively freezing much of the Council’s multilateral work.[69] This response highlighted deeper divisions between Russia and the Western bloc within the Council, straining the inclusivity that had previously characterized its operations.

Despite these challenges, the Council successfully transitioned its chairmanship from Russia to Norway in 2023, demonstrating its capacity to maintain institutional continuity under difficult circumstances.[70] However, relations with Russia within the Council remain strained, and questions persist about how the Council will navigate its relationship with Russia moving forward.[71] This period has underscored the increasing relevance of geopolitical considerations in the Council’s operations. While originally focused on environmental protection and sustainable development, the Arctic Council now finds itself grappling with the broader realities of global power politics and their impact on regional governance.[72]

Observer Status and Geopolitical Tensions

[edit]The observer status system within the Arctic Council has increasingly become a source of geopolitical tension. Observers include non-Arctic states such as China, Japan, and South Korea, alongside intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations. China’s inclusion as a permanent observer in 2013 sparked significant debate among member states.[73] While observers lack decision-making power, their participation has raised concerns about the influence of powerful non-Arctic actors on the Council’s governance.

China’s growing interest in Arctic resources and shipping routes has fueled broader strategic concerns.[74] Some opinions view its participation as a necessary step toward fostering international cooperation, while others see it as a potential risk to Arctic sovereignty.[75] These tensions reflect the challenge of balancing inclusivity with the need to safeguard regional interests, a dynamic that has become increasingly prominent in the Council’s activities.[76]

Discourse and Media Narratives

[edit]Media narratives have played a significant role in shaping perceptions of the Arctic Council and its activities. The China threat narrative, for example, portrays China as leveraging its observer status to pursue economic and strategic advantages in the Arctic.[77] These portrayals have contributed to broader geopolitical concerns, despite evidence that China has largely adhered to the Council’s cooperative norms.

Similarly, the concept of a resource rush in the Arctic has been amplified by media portrayals, framing the region as a potential hotspot for conflict over resources and maritime routes.[78][79] While such narratives have heightened attention to the Arctic’s strategic importance, they often oversimplify the Council’s efforts to maintain neutrality and collaborative governance. These dynamics illustrate the increasing complexity of balancing the Arctic Council’s original mission with growing global interest in the region.[80]

See also

[edit]- Arctic Economic Council

- Arctic cooperation and politics

- Arctic policy of Canada – Arctic Council Chair 2013–2015

- Arctic policy of the United States – Arctic Council Chair 2015–2017

- Antarctic Treaty System

- Ilulissat Declaration

- International Arctic Science Committee

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "About the Arctic Council". The Arctic Council. April 7, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Arctic Council: Founding Documents". Arctic Council Document Archive. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Axworthy, Thomas S. (March 29, 2010). "Canada bypasses key players in Arctic meeting". The Toronto Star. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Savage, Luiza Ch. (May 13, 2013). "Why everyone wants a piece of the Arctic". Maclean's. Rogers Digital Media. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Buixadé Farré, Albert; Stephenson, Scott R.; Chen, Linling; Czub, Michael; Dai, Ying; Demchev, Denis; Efimov, Yaroslav; Graczyk, Piotr; Grythe, Henrik; Keil, Kathrin; Kivekäs, Niku; Kumar, Naresh; Liu, Nengye; Matelenok, Igor; Myksvoll, Mari; O'Leary, Derek; Olsen, Julia; Pavithran .A.P., Sachin; Petersen, Edward; Raspotnik, Andreas; Ryzhov, Ivan; Solski, Jan; Suo, Lingling; Troein, Caroline; Valeeva, Vilena; van Rijckevorsel, Jaap; Wighting, Jonathan (October 16, 2014). "Commercial Arctic shipping through the Northeast Passage: Routes, resources, governance, technology, and infrastructure" (PDF). Polar Geography. 37 (4): 298–324. doi:10.1080/1088937X.2014.965769.

- ^ Lawson W Brigham (September–October 2021). "Think Again: The Arctic". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Brigham, L.; McCalla, R.; Cunningham, E.; Barr, W.; VanderZwaag, D.; Chircop, A.; Santos-Pedro, V.M.; MacDonald, R.; Harder, S.; Ellis, B.; Snyder, J.; Huntington, H.; Skjoldal, H.; Gold, M.; Williams, M.; Wojhan, T.; Williams, M.; Falkingham, J. (2009). Brigham, Lawson; Santos-Pedro, V.M.; Juurmaa, K. (eds.). Arctic marine shipping assessment (AMSA) (PDF). Norway: Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME), Arctic Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 28, 2016.

- ^ Koring, Paul (May 12, 2011). "Arctic treaty leaves much undecided". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "Joint Statement on Arctic Council Cooperation following Russia's Invasion of Ukraine". March 3, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ "Canada, six other states pull back from Arctic Council in protest over Ukraine". ctvnews.ca. March 3, 2022. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022.

- ^ Canada, Global Affairs (June 8, 2022). "Joint statement on limited resumption of Arctic Council cooperation". www.canada.ca. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Schreiber, Melody (June 8, 2022). "Arctic Council nations to resume limited cooperation — without Russia". ArcticToday. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Observers". Arctic Council Secretariat (2021). Arctic Council. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Ghattas, Kim (May 14, 2013). "Arctic Council: John Kerry steps into Arctic diplomacy". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "The EU and the Arctic Council". April 20, 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018.

- ^ Morcillo Pazos, Adrián & López Coca, Pau (2022). Comparison of EU and Chinese policies in the Arctic : new challenges in the Arctic after the Ukraine war. Quaderns IEE, Vol. 1, Nº. 2, pp. 87-114. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=8570467

- ^ "Brazilian ambassador to Russia: Brazil plans to become an observer country in the Arctic Council". arctic.ru. January 25, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Koivurova, T., & Heinämäki, L. (2006). The participation of indigenous peoples in international norm-making in the Arctic. Polar Record, 42(2), 101-109.

- ^ "Aleut International Association". Arctic Council. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Arctic Athabaskan Council". Arctic Council. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Gwich'in Council International". Arctic Council. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Gwich'in Council International". Arctic Council. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North". Arctic Council. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Saami Council". Arctic Council. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ "Arctic Parliamentarians". Arcticparl.org. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Northern Forum". Northern Forum. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Association of World Reindeer Herders". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ "The Arctic Council".

- ^ Press briefing, Arctic Council Annual Meeting, Nuuk May 2011 Stop talking – start protecting Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine 2012.

- ^ "13. Thirteenth Meeting of the Arctic Council in Salekhard, Russian Federation, May 11, 2023" – via oaarchive.arctic-council.org.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Troniak, Shauna (May 1, 2013). "Canada as Chair of the Arctic Council". HillNotes. Library of Parliament Research Publications. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ "Norway Chairs Arctic Council". Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "Canadian Chairmanship Program 2013–2015". Arctic Council. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "Secretary Tillerson Chairs 10th Arctic Council Ministerial Meeting". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Arctic Council Secretariat". Arctic Council. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ "The Kingdom of Denmark. Chairmanship of the Arctic Council 2009–2011". Arctic Council. April 29, 2009.

- ^ "Council of American Ambassadors". Council of American Ambassadors. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- ^ Category: About (April 7, 2011). "The Norwegian, Danish, Swedish common objectives for their Arctic Council chairmanships 2006–2013". Arctic Council. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "The Arctic Council". Arctic Council.

- ^ "Finland's Chairmanship of the Arctic Council in 2017–2019". Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

- ^ "Norway's Chairship - Arctic Council 2023-2025". May 12, 2023 – via oaarchive.arctic-council.org.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Travel of Deputy Secretary Burns to Sweden and Estonia". State.gov. May 14, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Secretariat, Arctic Council (2018). "Arctic Council Secretariat annual report 2017".

- ^ "Introducing Mathieu Parker: The new director of the Arctic Council Secretariat". Arctic Council.

- ^ "Terms, Reference and Guidelines" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 20, 2011.

- ^ Arctic Council Secretariat (2018). "Arctic Council Secretariat annual report 2017".

- ^ "Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme". Amap.no. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Conservation of Arctic Flora & Fauna (CAFF)". Caff.is. Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Emergency Prevention, Preparedness & Response". Eppr.arctic-council.org. June 4, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment". Pame.is. June 13, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Oops! We couldn't find this page for you". Arctic Portal.

- ^ "Sustainable Development Working Group". Portal.sdwg.org. August 27, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Arctic Contaminants Action Program (ACAP)". Acap.arctic-council.org. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Arctic Biodiversity Assessment Archived August 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council (Ottawa, Canada, 1996)". May 10, 2017. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Dams, Ties; van Schaik, Louise; Stoetman, Adája (2020). Presence before power: why China became a near-Arctic state (Report). Clingendael Institute. pp. 6–19. JSTOR resrep24677.5.

- ^ "Canada and the Kingdom of Denmark, together with Greenland, reach historic agreement on long-standing boundary disputes". Government of Canada. June 14, 2022. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Transnational Issues CIA World Fact Book". CIA. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ^ "Sea Changes". Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

- ^ Overfield, Cornell (April 21, 2021). "An Off-the-Shelf Guide to Extended Continental Shelves and the Arctic". Lawfare. Retrieved August 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Jill Mahoney. "Canadians rank Arctic sovereignty as top foreign-policy priority". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "Outsiders in the Arctic: The roar of ice cracking". The Economist. February 2, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "The Arctic: Five Critical Security Challenges | ASPAmerican Security Project". Americansecurityproject.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Arctic politics: Cosy amid the thaw". The Economist. March 24, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Rethinking the Top of the World: Arctic Security Public Opinion Survey Archived April 8, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, EKOS, January 2011

- ^ Janice Gross Stein And Thomas S. Axworthy. "The Arctic Council is the best way for Canada to resolve its territorial disputes". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ Berkman, Paul (June 23, 2014). "Stability and Peace in the Arctic Ocean through Science Diplomacy". Science & Diplomacy. 3 (2).

- ^ "U.S.-Russia Relations Are Frosty But They're Toasty On The Arctic Council". npr.org. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ^ Soliman-Hunter, T. (2022). War, exclusion, and geopolitical tension: the accepted normal in Arctic Council Governance? Lauda, 104, 64-69. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2022120769829

- ^ Fujio, O. (2022). Changing Arctic governance landscape: The Arctic Council navigating through geopolitical turbulence. Lauda, 104, 102-107. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2022120769801

- ^ Gustator. (2023, October 9). A time of great opportunity for reconfiguring the governance of the Arctic. Polar Journal. https://polarjournal.ch/en/2024/10/09/a-time-of-great-opportunity-for-reconfiguring-the-governance-of-the-arctic/

- ^ Soliman-Hunter, T. (2022). War, exclusion, and geopolitical tension: the accepted normal in Arctic Council Governance? Lauda, 104, 64-69. https://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe2022120769829

- ^ Willis, M., & Depledge, D. (2015). How we learned to stop worrying about China’s Arctic ambitions: understanding China’s admission to the Arctic Council, 2004-2013. In L. C. Jensen & G. Hønneland (Eds.), Handbook of the politics of the Arctic. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- ^ Lasserre, F. (2015). Case studies of shipping along Arctic routes. Polar Geography.

- ^ Willis, M., & Depledge, D. (2015). How we learned to stop worrying about China’s Arctic ambitions: understanding China’s admission to the Arctic Council, 2004-2013. In L. C. Jensen & G. Hønneland (Eds.), Handbook of the politics of the Arctic. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- ^ Filimonova, N., Obydenkova, A., & Vieira, V. G. R. (2023). Geopolitical and economic interests in environmental governance: explaining observer state status in the Arctic Council. Climate Change, 176(50). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03490-8

- ^ Willis, M., & Depledge, D. (2015). How we learned to stop worrying about China’s Arctic ambitions: understanding China’s admission to the Arctic Council, 2004-2013. In L. C. Jensen & G. Hønneland (Eds.), Handbook of the politics of the Arctic. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- ^ Rottem, S. V. (2020). "The Arctic Council: Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing Arctic." Polar Geography.

- ^ Lasserre, F. (2015). Case studies of shipping along Arctic routes. Polar Geography.

- ^ Filimonova, N., Obydenkova, A., & Vieira, V. G. R. (2023). Geopolitical and economic interests in environmental governance: explaining observer state status in the Arctic Council. Climate Change, 176(50). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-023-03490-8

Bibliography

[edit]- Danita Catherine Burke. 2020. Diplomacy and the Arctic Council. McGill Queen University Press.

- Wiseman, Matthew (2020). "The Future of the Arctic Council". In Coates, Ken; Holroyd, Carin (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Arctic Policy and Politics. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 439–452. ISBN 978-3-030-20556-0.

External links

[edit]- www.arctic-council.org – Arctic Council