Astral projection

| Part of a series on the |

| Paranormal |

|---|

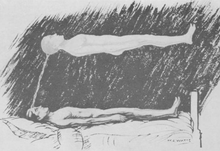

Astral projection (also known as astral travel, soul journey, soul wandering, spiritual journey, spiritual travel) is a term used in esotericism to describe an intentional out-of-body experience (OBE)[1][2] that assumes the existence of a subtle body, known as the astral body or body of light, through which consciousness can function separately from the physical body and travel throughout the astral plane.[3]

The idea of astral travel is ancient and occurs in multiple cultures. The term "astral projection" was coined and promoted by 19th-century Theosophists.[4] It is sometimes associated with dreams and forms of meditation.[5] Some individuals have reported perceptions similar to descriptions of astral projection that were induced through various hallucinogenic and hypnotic means (including self-hypnosis). There is no scientific evidence that there is a consciousness whose embodied functions are separate from normal neural activity or that one can consciously leave the body and make observations of the physical universe.[6] As a result, astral projection has been characterized as a pseudoscience.[7]

Accounts

[edit]Ancient Egyptian

[edit]

Similar concepts of soul travel appear in various other religious traditions. For example, ancient Egyptian teachings present the soul (ba) as having the ability to hover outside the physical body via the ka, or subtle body.[8]

Indigenous traditions

[edit]Amazon

[edit]The yaskomo of the Waiwai is believed to have the ability to perform a soul flight that can serve several functions, such as healing; flying to the sky to consult cosmological beings (the Moon or the Brother of the Moon) to obtain a name for a newborn baby; flying to the cave of peccaries' mountains to ask the father of peccaries for abundance of game; or flying deep down into a river to seek the aid of other beings.[9]

Inuit

[edit]In some Inuit groups, individuals with special capabilities, known as angakkuq, are said to be able to travel to (mythological) remote places, and report their experiences and important matters back to their community. Those abilities would be unavailable to individuals with normal capabilities.[10] Among other things, an angakkuq was said to have the ability to stop bad hunting luck or heal a sick person.[11]

Hindu

[edit]Similar ideas such as the Liṅga Śarīra are found in ancient Hindu scriptures such as the Yogavashishta-Maharamayana of Valmiki.[8] Modern Indians who have vouched for astral projection include Paramahansa Yogananda who witnessed Swami Pranabananda doing a miracle through a possible astral projection.[12]

The Indian spiritual teacher Meher Baba described one's use of astral projection:

In the advancing stages leading to the beginning of the path, the aspirant becomes spiritually prepared for being entrusted with free use of the forces of the inner world of the astral bodies. He may then undertake astral journeys in his astral body, leaving the physical body in sleep or wakefulness. The astral journeys that are taken unconsciously are much less important than those undertaken with full consciousness and as a result of deliberate volition. This implies conscious use of the astral body. Conscious separation of the astral body from the outer vehicle of the gross body has its own value in making the soul feel its distinction from the gross body and in arriving at fuller control of the gross body. One can, at will, put on and take off the external gross body as if it were a cloak and use the astral body for experiencing the inner world of the astral and for undertaking journeys through it, if and when necessary. ... The ability to undertake astral journeys therefore involves considerable expansion of one's scope for experience. It brings opportunities for promoting one's own spiritual advancement, which begins with the involution of consciousness.[13]

Astral projection is one of the siddhis ('magical powers') considered achievable by yoga practitioners through self-disciplined practice. In the epic Mahabharata, Drona leaves his physical body to see if his son is alive.

Japanese

[edit]In Japanese mythology, an ikiryō (生霊, also read as shōryō, seirei, or ikisudama) is a manifestation of the soul of a living person separately from their body.[14] Traditionally, if someone holds a sufficient grudge against another person, it is believed that a part or the whole of their soul can temporarily leave their body and appear before the target of their hate in order to curse or otherwise harm them, similar to an evil eye. Souls are also believed to leave a living body when the body is extremely sick or comatose; but such ikiryō are not malevolent.[15]

Taoist

[edit]Taoist alchemical practice involves creation of an energy body by breathing meditations, drawing energy into a 'pearl' that is then circulated.[16]

Xiangzi ... with a drum as his pillow fell fast asleep, snoring and motionless. His primordial spirit, however, went straight into the banquet room and said, "My lords, here I am again." When Tuizhi walked with the officials to take a look, there really was a Taoist sleeping on the ground and snoring like thunder. Yet inside, in the side room, there was another Taoist beating a fisher drum and singing Taoist songs. The officials all said, "Although there are two different people, their faces and clothes are exactly alike. Clearly he is a divine immortal who can divide his body and appear in several places at once. ..." At that moment, the Taoist in the side room came walking out, and the Taoist sleeping on the ground woke up. The two merged into one.[17]

Judaic and Christian

[edit]Carrington, Muldoon, Peterson, and Williams say that the subtle body is attached to the physical body by means of a psychic silver cord.[18] The final chapter of the Book of Ecclesiastes is often cited in this respect: "Before the silver cord be loosed, or the golden bowl be broken, or the pitcher be shattered at the fountain, or the wheel be broken at the cistern."[19] Rabbi Nosson Scherman, however, contends that the context points to this being merely a metaphor, comparing the body to a machine, with the silver cord referring to the spine.[20]

James Hankins argues that Paul's Second Epistle to the Corinthians refers to the astral planes:[21] "I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven. Whether it was in the body or out of the body I do not know—God knows."[22]

Western esotericism

[edit]According to the classical, medieval, renaissance Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, and later Theosophist and Rosicrucian thought, the 'astral body' is an intermediate body of light linking the rational soul to the physical body while the astral plane is an intermediate world of light between Heaven and Earth, composed of the spheres of the planets and stars. These astral spheres were held to be populated by angels, demons, and spirits.[23][24]

In the Neoplatonism of Plotinus, for example, the individual is a microcosm ("small world") of the universe (the macrocosm or "great world"). "The rational soul...is akin to the great Soul of the World" while "the material universe, like the body, is made as a faded image of the Intelligible".[25] Each succeeding plane of manifestation is causal to the next, a world-view known as emanationism; "from the One proceeds Intellect, from Intellect Soul, and from Soul—in its lower phase, or that of Nature—the material universe".[26] The idea of the astral figured prominently in the work of the nineteenth-century French occultist Eliphas Levi, whence it was adopted and developed further by Theosophy, and used afterwards by other esoteric movements.

The subtle bodies, and their associated planes of existence, form an essential part of some esoteric systems that deal with astral phenomena. Often these bodies and their planes of existence are depicted as a series of concentric circles or nested spheres, with a separate body traversing each realm.[27]

Terminology

[edit]The expression "astral projection" came to be used in two different ways. For the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn[28] and some Theosophists,[29] it retained the classical and medieval philosophers' meaning of journeying to other worlds, heavens, hells, the astrological spheres and other landscapes in the body of light; but outside these circles the term was increasingly applied to non-physical travel around the physical world.[30]

Though this usage continues to be widespread, the term, "etheric travel", used by some later Theosophists, offers a useful distinction. Some experimenters say they visit different times and/or places: etheric, then, is used to represent the sense of being out of the body in the physical world; whereas astral may connote some alteration in time-perception. Robert Monroe describes the former type of projection as "Locale I" or the "Here-Now", involving people and places that exist:[31] Robert Bruce calls it the "Real Time Zone" (RTZ) and describes it as the non-physical dimension-level closest to the physical.[32] This etheric body is usually, though not always, invisible but is often perceived by the experient as connected to the physical body during separation by a silver cord. Some link falling dreams with projection.[33]

According to Max Heindel, the etheric double serves as a medium between the astral and physical realms. In his system the ether, also called prana, is the vital force that empowers the physical forms to change. From his descriptions it can be inferred that, to him, when one views the physical during an out-of-body experience, one is not technically in the astral realm at all.[34]

Other experiments may describe a domain that has no parallel to any known physical setting. Environments may be populated or unpopulated, artificial, natural or abstract, and the experience may be beatific, horrific or neutral. A common Theosophical belief is that one may access a compendium of mystical knowledge called the Akashic records. In many accounts the experiencer correlates the astral world with the world of dreams. Some even report seeing other dreamers enacting dream scenarios unaware of their wider environment.[35]

The astral environment may also be divided into levels or sub-planes by theorists, but there are many different views in various traditions concerning the overall structure of the astral planes: they may include heavens and hells and other after-death spheres, transcendent environments, or other less-easily characterized states.[31][33][35]

Scientific reception

[edit]There is no known scientific evidence that astral projection as an objective phenomenon exists,[6][7][36] although there are cases of patients having experiences suggestive of astral projection from brain stimulation treatments and hallucinogenic drugs, such as ketamine, phencyclidine, and DMT.[36] Subjects in parapsychological experiments have attempted to project their astral bodies to distant rooms and see what was happening. However, such experiments have not produced clear results.[37]

Psychologist Donovan Rawcliffe wrote that astral projection can be explained by delusion, hallucination, and vivid dreams.[38] Arthur W. Wiggins wrote that purported evidence of the ability to astrally travel great distances and give descriptions of places visited is predominantly anecdotal and considers astral travel an illusion. He looks to neuroanatomy, prior knowledge, and human belief and imagination to provide prosaic explanations for those who experience it.[39] Robert Todd Carroll writes that the main evidence to support claims of astral travel is anecdotal and comes "in the form of testimonials of those who claim to have experienced being out of their bodies when they may have been out of their minds."[40]

Notable practitioners

[edit]

Emanuel Swedenborg was one of the first practitioners to write extensively about the out-of-body experience, in his Spiritual Diary (1747–1765). In her book, My Religion, Helen Keller tells of her beliefs in Swedenborgianism and how she once traveled astrally to Athens:

I have been far away all this time, and I haven't left the room...It was clear to me that it was because I was a spirit that I had so vividly 'seen' and felt a place a thousand miles away. Space was nothing to spirit![41]

In occult traditions, practices range from inducing trance states to the mental construction of a second body, called the "body of light" by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), through visualization and controlled breathing, followed by the transfer of consciousness to the secondary body by a mental act of will.[42][43]

There are many 20th-century publications on astral projection, although only a few writers continue to be cited. These include Edgar Cayce (1877–1945), Hereward Carrington (1880–1958),[44] Oliver Fox (1885–1949),[45] Sylvan Muldoon (1903–1969),[46] and Robert Monroe (1915–1995).[47]

Robert Monroe's accounts of journeys to other realms (1971–1994) popularized the term "OBE" and were translated into a large number of languages. Though his books themselves only placed secondary importance on descriptions of method, Monroe also founded an institute dedicated to research, exploration and non-profit dissemination of auditory technology for assisting others in achieving projection and related altered states of consciousness.[47]

Carlos Castaneda (1925–1998) discusses his teacher Don Juan's beliefs about "the double" and its abilities in his books Tales of Power (1974), The Second Ring of Power (1977), and The Art of Dreaming (1993).[48] Florinda Donner, a student of Castaneda, further describes methods of using the double to access the physical world while dreaming and access the dream world while in a waking dream state in her 1992 book, Being-in-Dreaming.[49]

Michael Crichton (1942–2008) gives lengthy and detailed explanations and experience of astral projection in his 1988 non-fiction book Travels. Robert Bruce,[50] William Buhlman,[51] Marilynn Hughes,[52] and Albert Taylor[53] have discussed their theories and findings on the syndicated show Coast to Coast AM several times.

See also

[edit]- Bilocation – Alleged supernatural ability to be in two places at once

- Dream yoga – Tibetan meditation practice

- Eckankar – Religious movement founded in 1965 by Paul Twitchell

- Hypnagogia – State of consciousness leading into sleep

- Lucid dream – Dream where one is aware that one is dreaming

- Luminous mind – Term used in Buddhist doctrine

- Merkabah mysticism – School of early Jewish mysticism

- Remote viewing – Pseudoscientific concept

- Scrying – Practice of seeking visions in a reflective surface

- Simulated reality – Concept of a false version of reality

- Sleep paralysis – Sleeping disorder

- Tattva vision – Subject related to ESP

- Teleportation – Transfer between two points

- Worship of heavenly bodies – Worship of stars and other heavenly bodies as deities

- Yoga nidra – State of consciousness between waking and sleeping induced by a guided meditation

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Astral Projection: An Intentional Out-of-body Experience".

- ^ Myers 2014, p. 52.

- ^ Park 2008, pp. 90–91; Crow 2012.

- ^ Crow 2012.

- ^ Zusne & Jones 1989, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Regal 2009, p. 29: "Other than anecdotal eyewitness accounts, there is no known evidence of the ability to astral project, the existence of other planes, or of the Akashic Record."

- ^ a b Hines 2003, pp. 103–106.

- ^ a b Melton 1996

- ^ Fock 1963, p. 16.

- ^ Hoppál 1975, p. 228.

- ^ Kleivan & Sonne 1985, pp. 7–8, 12, 23–24, 26–31; Merkur 1985, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Wikisource:Autobiography of a Yogi/Chapter 3

- ^ Meher Baba 1967, pp. 90, 91.

- ^ Clarke 2000, p. 247.

- ^ Chopra 2005, p. 144.

- ^ Chia 2007, pp. 89ff.

- ^ Erzeng 2007, pp. 207–209.

- ^ Muldoon & Carrington 1929; Peterson 2013, chapters 5, 17, 22.

- ^ Ecclesiastes 12:6

- ^ Scherman 2011, p. 1150.

- ^ Hankins 2003.

- ^ 2 Corinthians 12:2

- ^ Dodds in Proclus 1963, Appendix.

- ^ Pagel 1967, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Gregory 1991, p. 12.

- ^ Gregory 1991, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Besant 1897, p. [page needed].

- ^ Cicero & Cicero 2003, p. [page needed].

- ^ Powell 1927, p. 7.

- ^ Judge 1893, ch. 5.

- ^ a b Monroe 1977, p. 60.

- ^ Bruce 1999, pp. 25–27, 30–31.

- ^ a b Bruce 1999, p. [page needed].

- ^ Heindel 1911, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Monroe 1985, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Park 2008, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Blackmore 1991.

- ^ Rawcliffe 1987, p. 123.

- ^ Wynn, Wiggins & Harris 2001, pp. 95ff.

- ^ Carroll 2003, p. 33ff.

- ^ Keller 1927, p. 33.

- ^ Greer 1967.

- ^ Crowley 1988, ch. XIII: "The Body of Light, Its Power and Development".

- ^ Pettit 2013, p. 93.

- ^ DeKorne 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Rickard & Michell 2007, pp. 106, 123–4.

- ^ a b Biddle & Thompson 2013, p. 176.

- ^ Kramer & Larkin 1993, pp. 74–85.

- ^ Donner 1992.

- ^ "Robert Bruce – Biography & Interviews". Coast to Coast AM.

- ^ "William Buhlman – Biography & Interviews". Coast to Coast AM.

- ^ "Marilynn Hughes – Biography & Interviews". Coast to Coast AM.

- ^ "Albert Taylor – Biography & Interviews". Coast to Coast AM.

Works cited

[edit]- Besant, Annie Wood (1897). The Ancient Wisdom: An Outline of Theosophical Teachings. Theosophical Publishing Society. ISBN 978-0524027127.

- Biddle, Ian; Thompson, Marie, eds. (2013). Sound, Music, Affect: Theorizing Sonic Experience. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1441101761.

- Blackmore, Susan (1991). "Near-Death Experiences: In or out of the body?". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 16. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. pp. 34–45. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- Bruce, Robert (1999). Astral Dynamics: A New Approach to Out-of-Body Experiences. Hampton Roads Publishing. ISBN 1-57174-143-7.

- Carroll, Robert Todd (2003). The Skeptic's Dictionary: A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amusing Deceptions, and Dangerous Delusions. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-27242-6.

- Chia, Mantak (2007) [1989]. Fusion of the Five Elements. Destiny Books. ISBN 978-1594771033.

- Chopra, R. (2005). Academic Dictionary Of Mythology. India: Isha Books. ISBN 978-8182052321.

- Cicero, Chic; Cicero, Tabatha (2003). The Essential Golden Dawn: An Introduction to High Magic. St. Paul, MN: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN 0-7387-0310-9.

- Clarke, Peter Bernard (2000). Japanese new religions: in global perspective. Vol. 1999 (annotated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0700711857.

- Crow, John L. (2012). "Taming the astral body: the Theosophical Society's ongoing problem of emotion and control". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 80 (3): 691–717. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfs042.

- Crowley, Aleister (1988). Symonds, John; Grant, Kenneth (eds.). Magick. London: Guild Publishing.

- DeKorne, Jim (2011). Psychedelic Shamanism, Updated Edition: The Cultivation, Preparation, and Shamanic Use of Psychotropic Plants. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1556439995.

- Donner, Florinda (1992). Being-in-Dreaming: An Initiation Into the Sorcerers' World. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-250192-9.

- Erzeng, Yang (2007). The Story of Han Xiangzi. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295986906.

- Fock, Niels (1963). Waiwai: Religion and society of an Amazonian tribe. Nationalmuseets Skrifter Etnografisk Række [Ethnographic Series]. Vol. VIII. Copenhagen: The National Museum of Denmark.

- Greer, John (1967). "Astral Projection". The New Encyclopedia of the Occult. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 978-1567183368.

- Gregory, John (1991). The Neoplatonists. Kyle Cathie. ISBN 978-1856260220.

- Hankins, James (2003). "Ficino, Avicenna and the Occult Powers of the Rational Soul". In Meroi, Fabrizio; Scapparone, Elisabetta (eds.). La magia nell'Europa moderna: Tra antica sapienza e filosofia naturale. Atti del convegno (Istituto nazionale di studi sul rinascimento) 23. Florence: Leo S. Olschki. pp. I, 35–52.

- Heindel, Max (1911). "Chapter IV: The Constitution of Man: Vital Body – Desire Body – Mind". The Rosicrucian Mysteries. Rosicrucian Fellowship. ISBN 0911274863 – via Rosicrucian.com.

- Hines, Terence (2003). Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-979-4.

- Hoppál, Mihály (1975). "Az uráli népek hiedelemvilága és a samanizmus" [The belief system of Uralic peoples and the shamanism]. In Hajdú, Péter (ed.). Uráli népek: Nyelvrokonaink kultúrája és hagyományai [Uralic peoples: Culture and traditions of our linguistic relatives] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Corvina Kiadó. pp. 211–233. ISBN 978-963-13-0900-3.

- Judge, William (1893). The Ocean of Theosophy (2nd ed.). Theosopical Publishing House.

- Keller, Helen (1927). My Religion (1st ed.). Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Kleivan, Inge; Sonne, B. (1985). Iconography of Religions: Arctic peoples. Eskimos, Greenland and Canada. Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-07160-5.

- Kramer, K.; Larkin, J. S. (1993). Death Dreams: Unveiling Mysteries of the Unconscious Mind. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809133499.

- Meher Baba (1967). Discourses. Vol. II. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. ISBN 1-880619-09-1.

- Melton, J. Gordon (1996). "Out-of-the-body Travel". Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology: M-Z. Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. Thomson Gale. ISBN 978-0810394872.

- Merkur, Daniel (1985). Becoming Half Hidden: Shamanism and Initiation among the Inuit. Stockholm Studies in Comparative Religion. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. ISBN 978-91-22-00752-4.

- Monroe, Robert (1977) [1971]. Journeys Out of the Body. Harmony/Rodale. ISBN 0-385-00861-9.

- Monroe, Robert (1985). Far Journeys. Harmony/Rodale. ISBN 0385231822.

- Muldoon, Sylvan; Carrington, Hereward (1929). Projection of the Astral Body. Rider and Company. ISBN 0-7661-4604-9.

- Myers, Frederic W. H. (2014). "Astral Projection". Journal for Spiritual & Consciousness Studies. 37 (1).

- Pagel, Walter (1967). William Harvey's Biological Ideas. Karger Publishers. ISBN 978-3805509626.

- Park, Robert L. (2008). Superstition: Belief in the Age of Sciences. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400828777.

- Peterson, R. (2013). Out-Of-Body Experiences: How to Have Them and What to Expect. Hampton Roads. ISBN 978-1571746993.

- Pettit, Michael (2013). The Science of Deception: Psychology and Commerce in America. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226923741.

- Powell, Arthur E. (1927). The Astral Body and Other Astral Phenomena. London; Wheaton, Ill; Adyar, Chennai: The Theosophical Publishing House.

- Proclus (1963). The Elements of Theology: A revised text with translation, introduction, and commentary. Translated by E. R. Dodds (2nd ed.).

- Rawcliffe, Donovan (1987). Occult and Supernatural phenomena. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486255514.

- Regal, Brian (2009). Pseudoscience: A Critical Encyclopedia. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313355073.

- Rickard, B.; Michell, J. (2007). The Rough Guide to Unexplained Phenomena. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1843537083.

- Scherman, Nosson, ed. (2011). The ArtScroll English Tanach. ArtScroll Series (First ed.). Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah Publications. ISBN 978-1422610657.

- Wynn, Charles M.; Wiggins, Arthur W.; Harris, Sidney (2001). Quantum leaps in the wrong direction: where real science ends – and pseudoscience begins. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0309073097.

- Zusne, Leonard; Jones, Warren H. (1989). Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0805805086.

Further reading

[edit]- Nema (1995). Maat Magic: a Guide to Self-Initiation. York Beach, Maine: Samuel Weiser. ISBN 0-87728-827-5.