Levodopa

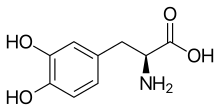

Skeletal formula of levodopa | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛlˈdoʊpə/, /ˌlɛvoʊˈdoʊpə/ |

| Trade names | Larodopa, Dopar, Inbrija, others |

| Other names | L-DOPA |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a619018 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, inhalation, enteral (tube), subcutaneous (as foslevodopa) |

| Drug class | Dopamine precursor; Dopamine receptor agonist |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30% |

| Metabolism | Aromatic-l-amino-acid decarboxylase |

| Metabolites | • Dopamine |

| Elimination half-life | 0.75–1.5 hours |

| Excretion | Renal 70–80% |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H11NO4 |

| Molar mass | 197.190 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Levodopa, also known as L-DOPA and sold under many brand names, is a dopaminergic medication which is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and certain other conditions like dopamine-responsive dystonia and restless legs syndrome.[3] The drug is usually used and formulated in combination with a peripherally selective aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD) inhibitor like carbidopa or benserazide.[3] Levodopa is taken by mouth, by inhalation, through an intestinal tube, or by administration into fat (as foslevodopa).[3]

Side effects of levodopa include nausea, the wearing-off phenomenon, dopamine dysregulation syndrome, and levodopa-induced dyskinesia, among others.[3] The drug is a centrally permeable monoamine precursor and prodrug of dopamine and hence acts as a dopamine receptor agonist.[3] Chemically, levodopa is an amino acid, a phenethylamine, and a catecholamine.[3]

Levodopa was first synthesized and isolated in the early 1910s.[3] The antiparkinsonian effects of levodopa were discovered in the 1950s and 1960s.[3] Following this, it was introduced for the treatment of Parkinson's disease in 1970.[3]

Medical uses

[edit]Levodopa crosses the protective blood–brain barrier, whereas dopamine itself cannot.[3][4] Thus, levodopa is used to increase dopamine concentrations in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, Parkinsonism, dopamine-responsive dystonia and Parkinson-plus syndrome. The therapeutic efficacy is different for different kinds of symptoms. Bradykinesia and rigidity are the most responsive symptoms while tremors are less responsive to levodopa therapy. Speech, swallowing disorders, postural instability, and freezing gait are the least responsive symptoms.[5]

Once levodopa has entered the central nervous system, it is converted into dopamine by the enzyme aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AAAD), also known as DOPA decarboxylase (DDC). Pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6) is a required cofactor in this reaction, and may occasionally be administered along with levodopa, usually in the form of pyridoxine. Because levodopa bypasses the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting step in dopamine synthesis, it is much more readily converted to dopamine than tyrosine, which is normally the natural precursor for dopamine production.

In humans, conversion of levodopa to dopamine does not only occur within the central nervous system. Cells in the peripheral nervous system perform the same task. Thus administering levodopa alone will lead to increased dopamine signaling in the periphery as well. Excessive peripheral dopamine signaling is undesirable as it causes many of the adverse side effects seen with sole levodopa administration. To bypass these effects, it is standard clinical practice to coadminister (with levodopa) a peripheral DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (DDCI) such as carbidopa (medicines containing carbidopa, either alone or in combination with levodopa, are branded as Lodosyn[6] (Aton Pharma)[7] Sinemet (Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited), Pharmacopa (Jazz Pharmaceuticals), Atamet (UCB), Syndopa and Stalevo (Orion Corporation) or with a benserazide (combination medicines are branded Madopar or Prolopa), to prevent the peripheral synthesis of dopamine from levodopa). However, when consumed as a botanical extract, for example from M pruriens supplements, a peripheral DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor is not present.[8]

Inbrija (previously known as CVT-301) is an inhaled powder formulation of levodopa indicated for the intermittent treatment of "off episodes" in patients with Parkinson's disease currently taking carbidopa/levodopa.[9] It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration on 21 December 2018, and is marketed by Acorda Therapeutics.[10]

Coadministration of pyridoxine without a DDCI accelerates the peripheral decarboxylation of levodopa to such an extent that it negates the effects of levodopa administration, a phenomenon that historically caused great confusion.

In addition, levodopa, co-administered with a peripheral DDCI, is efficacious for the short-term treatment of restless leg syndrome.[11]

The two types of response seen with administration of levodopa are:

- The short-duration response is related to the half-life of the drug.

- The longer-duration response depends on the accumulation of effects over at least two weeks, during which ΔFosB accumulates in nigrostriatal neurons. In the treatment of Parkinson's disease, this response is evident only in early therapy, as the inability of the brain to store dopamine is not yet a concern.

Available forms

[edit]Levodopa is available, alone and/or in combination with carbidopa, in the form of immediate-release oral tablets and capsules, extended-release oral tablets and capsules, orally disintegrating tablets, as a powder for inhalation, and as an enteral suspension or gel (via intestinal tube).[12][13] In terms of combination formulations, it is available with carbidopa (as levodopa/carbidopa), with benserazide (as levodopa/benserazide), and with both carbidopa and entacapone (as levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone).[12][13][14][15] In addition to levodopa itself, certain prodrugs of levodopa are available, including melevodopa (melevodopa/carbidopa) (used orally) and foslevodopa (foslevodopa/foscarbidopa) (used subcutaneously).[16][17][18]

Side effects

[edit]The side effects of levodopa may include:

- Hypertension, especially if the dosage is too high

- Arrhythmias, although these are uncommon

- Nausea, which is often reduced by taking the drug with food, although protein reduces drug absorption. Levodopa is an amino acid, so protein competitively inhibits levodopa absorption.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Disturbed respiration, which is not always harmful, and can actually benefit patients with upper airway obstruction

- Hair loss

- Disorientation and confusion

- Extreme emotional states, particularly anxiety, but also excessive libido

- Vivid dreams or insomnia

- Auditory or visual hallucinations

- Effects on learning; some evidence indicates it improves working memory, while impairing other complex functions

- Somnolence and narcolepsy

- A condition similar to stimulant psychosis

Although many adverse effects are associated with levodopa, in particular psychiatric ones, it has fewer than other antiparkinsonian agents, such as anticholinergics and dopamine receptor agonists.

More serious are the effects of chronic levodopa administration in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, which include:

- End-of-dose deterioration of function

- "On/off" oscillations

- Freezing during movement

- Dose failure (drug resistance)

- Dyskinesia at peak dose (levodopa-induced dyskinesia)

- Possible dopamine dysregulation: The long-term use of levodopa in Parkinson's disease has been linked to the so-called dopamine dysregulation syndrome.[19]

Rapidly decreasing the dose of levodopa can result in neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Clinicians try to avoid these side effects and adverse reactions by limiting levodopa doses as much as possible until absolutely necessary.

Metabolites of dopamine, such as DOPAL, are known to be dopaminergic neurotoxins. The long term use of levodopa increases oxidative stress through monoamine oxidase led enzymatic degradation of synthesized dopamine causing neuronal damage and cytotoxicity. The oxidative stress is caused by the formation of reactive oxygen species (H2O2) during the monoamine oxidase led metabolism of dopamine. It is further perpetuated by the richness of Fe2+ ions in striatum via the Fenton reaction and intracellular autooxidation. The increased oxidation can potentially cause mutations in DNA due to the formation of 8-oxoguanine, which is capable of pairing with adenosine during mitosis.[20] See also the catecholaldehyde hypothesis.

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Levodopa is a dopamine precursor and prodrug of dopamine and hence acts as a non-selective dopamine receptor agonist, including of the D1-like receptors (D1, D5) and the D2-like receptors (D2, D3, D4).[3]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The bioavailability of levodopa is 30%.[3] It is metabolized into dopamine by aromatic-l-amino-acid decarboxylase (AAAD) in the central nervous system and periphery.[3] The elimination half-life of levodopa is 0.75 to 1.5 hours.[3] It is excreted 70–80% in urine.

Chemistry

[edit]Levodopa is an amino acid and a substituted phenethylamine and catecholamine.[3]

Analogues and prodrugs of levodopa include melevodopa, etilevodopa, foslevodopa, and XP-21279. Some of these, like melevodopa and foslevodopa, are approved for the treatment of Parkinson's disease similarly to levodopa.

Other analogues include methyldopa, an antihypertensive agent, and droxidopa (L-DOPS), a norepinephrine precursor and prodrug.

6-Hydroxydopa, a prodrug of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), is a potent dopaminergic neurotoxin used in scientific research.

History

[edit]Levodopa was first synthesized in 1911 by Torquato Torquati from the Vicia faba bean.[3] It was first isolated in 1913 by Marcus Guggenheim from the V. faba bean.[3] Guggenheim tried levodopa at a dose of 2.5 mg and thought that it was inactive aside from nausea and vomiting.[3]

In work that earned him a Nobel Prize in 2000, Swedish scientist Arvid Carlsson first showed in the 1950s that administering levodopa to animals with drug-induced (reserpine) Parkinsonian symptoms caused a reduction in the intensity of the animals' symptoms. In 1960 or 1961 Oleh Hornykiewicz, after discovering greatly reduced levels of dopamine in autopsied brains of patients with Parkinson's disease,[3][21] published together with the neurologist Walther Birkmayer dramatic therapeutic antiparkinson effects of intravenously administered levodopa in patients.[22] This treatment was later extended to manganese poisoning and later Parkinsonism by George Cotzias and his coworkers,[23] who used greatly increased oral doses, for which they won the 1969 Lasker Prize.[24][25] The first study reporting improvements in patients with Parkinson's disease resulting from treatment with levodopa was published in 1968.[26]

Levodopa was first marketed in 1970 by Roche under the brand name Larodopa.[3]

The neurologist Oliver Sacks describes this treatment in human patients with encephalitis lethargica in his 1973 book Awakenings, upon which the 1990 movie of the same name is based.

Carbidopa was added to levodopa in 1974 and this improved its tolerability.[3]

Society and culture

[edit]Names

[edit]Levodopa is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, USP, BAN, DCF, DCIT, and JAN.[27][28][14][15]

Research

[edit]Novel formulations and prodrugs

[edit]New levodopa formulations for use by other routes of administration, such as subcutaneous administration, are being developed.[29][30]

Levodopa prodrugs, with the potential for better pharmacokinetics, reduced fluctuations in levodopa levels, and reduced "on–off" phenomenon, are being researched and developed.[31][32]

Depression

[edit]Levodopa has been reported to be inconsistently effective as an antidepressant in the treatment of depressive disorders.[33][34] However, it was found to enhance psychomotor activation in people with depression.[33][34]

Motivational disorders

[edit]Levodopa has been found to increase the willingness to exert effort for rewards in humans and hence appears to show pro-motivational effects.[35][36] Other dopaminergic agents have also shown pro-motivational effects and may be useful in the treatment of motivational disorders.[37]

Age-related macular degeneration

[edit]In 2015, a retrospective analysis comparing the incidence of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) between patients taking versus not taking levodopa found that the drug delayed onset of AMD by around 8 years. The authors state that significant effects were obtained for both dry and wet AMD.[38][non-primary source needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Howard ST, Hursthouse MB, Lehmann CW, Poyner EA (1995). "Experimental and theoretical determination of electronic properties in Ldopa". Acta Crystallogr. B. 51 (3): 328–337. Bibcode:1995AcCrB..51..328H. doi:10.1107/S0108768194011407. S2CID 96802274.

- ^ a b "Levodopa Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Whitfield AC, Moore BT, Daniels RN (December 2014). "Classics in chemical neuroscience: levodopa". ACS Chem Neurosci. 5 (12): 1192–1197. doi:10.1021/cn5001759. PMID 25270271.

- ^ Hardebo JE, Owman C (July 1980). "Barrier mechanisms for neurotransmitter monoamines and their precursors at the blood-brain interface". Annals of Neurology. 8 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1002/ana.410080102. PMID 6105837. S2CID 22874032.

- ^ Ovallath S, Sulthana B (2017). "Levodopa: History and Therapeutic Applications". Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 20 (3): 185–189. doi:10.4103/aian.AIAN_241_17. PMC 5586109. PMID 28904446.

- ^ "Medicare D". Medicare. 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Lodosyn", Drugs, n.d., retrieved 12 November 2012

- ^ Cohen PA, Avula B, Katragunta K, Khan I (October 2022). "Levodopa Content of Mucuna pruriens Supplements in the NIH Dietary Supplement Label Database". JAMA Neurology. 79 (10): 1085–1086. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2184. PMC 9361182. PMID 35939305.

- ^ "Inbrija Prescribing Information" (PDF). Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "Acorda Therapeutics Announces FDA Approval of INBRIJA™ (levodopa inhalation powder)". ir.acorda.com. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Scholz H, Trenkwalder C, Kohnen R, Riemann D, Kriston L, Hornyak M, et al. (Cochrane Movement Disorders Group) (February 2011). "Levodopa for restless legs syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (2): CD005504. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005504.pub2. PMC 8889887. PMID 21328278.

- ^ a b Livingston C, Monroe-Duprey L (April 2024). "A Review of Levodopa Formulations for the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease Available in the United States". J Pharm Pract. 37 (2): 485–494. doi:10.1177/08971900221151194. PMID 36704966.

- ^ a b "Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs". accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ a b Schweizerischer Apotheker-Verein (2004). Index Nominum: International Drug Directory. Medpharm Scientific Publishers. p. 699. ISBN 978-3-88763-101-7. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Levodopa (International database)". Drugs.com. 2 September 2024. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Nakmode DD, Day CM, Song Y, Garg S (May 2023). "The Management of Parkinson's Disease: An Overview of the Current Advancements in Drug Delivery Systems". Pharmaceutics. 15 (5): 1503. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15051503. PMC 10223383. PMID 37242745.

- ^ Fabbri M, Barbosa R, Rascol O (April 2023). "Off-time Treatment Options for Parkinson's Disease". Neurol Ther. 12 (2): 391–424. doi:10.1007/s40120-022-00435-8. PMC 10043092. PMID 36633762.

- ^ Lees A, Tolosa E, Stocchi F, Ferreira JJ, Rascol O, Antonini A, et al. (January 2023). "Optimizing levodopa therapy, when and how? Perspectives on the importance of delivery and the potential for an early combination approach". Expert Rev Neurother. 23 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1080/14737175.2023.2176220. hdl:10451/56313. PMID 36729395.

- ^ Merims D, Giladi N (2008). "Dopamine dysregulation syndrome, addiction and behavioral changes in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 14 (4): 273–80. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.09.007. PMID 17988927.

- ^ Dorszewska J, Prendecki M, Lianeri M, Kozubski W (February 2014). "Molecular Effects of L-dopa Therapy in Parkinson's Disease". Current Genomics. 15 (1): 11–7. doi:10.2174/1389202914666131210213042. PMC 3958954. PMID 24653659.

- ^ Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O (December 1960). "[Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system]". Klinische Wochenschrift. 38 (24): 1236–9. doi:10.1007/BF01485901. PMID 13726012. S2CID 32896604.

- ^ Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O (November 1961). "[The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia]". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 73: 787–8. PMID 13869404.

- ^ Cotzias GC, Papavasiliou PS, Gellene R (July 1969). "L-dopa in parkinson's syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 281 (5): 272. doi:10.1056/NEJM196907312810518. PMID 5791298.

- ^ "Lasker Award". 1969. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016., retrieved 1 April 2013

- ^ Simuni T, Hurtig H (2008). "Levadopa: A Pharmacologic Miracle Four Decades Later". In Factor SA, Weiner WJ (eds.). Parkinson's Disease: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-934559-87-1 – via Google eBook.

- ^ Cotzias GC (March 1968). "L-Dopa for Parkinsonism". The New England Journal of Medicine. 278 (11): 630. doi:10.1056/nejm196803142781127. PMID 5637779.

- ^ Elks J (2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer US. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Netherlands. p. 164. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Retrieved 28 September 2024.

- ^ Doggrell SA (2023). "Continuous subcutaneous levodopa-carbidopa for the treatment of advanced Parkinson's disease: is it an improvement on other delivery?". Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 20 (9): 1189–1199. doi:10.1080/17425247.2023.2253146. PMID 37634938.

- ^ Urso D, Chaudhuri KR, Qamar MA, Jenner P (November 2020). "Improving the Delivery of Levodopa in Parkinson's Disease: A Review of Approved and Emerging Therapies". CNS Drugs. 34 (11): 1149–1163. doi:10.1007/s40263-020-00769-7. PMID 33146817.

- ^ Cacciatore I, Ciulla M, Marinelli L, Eusepi P, Di Stefano A (April 2018). "Advances in prodrug design for Parkinson's disease". Expert Opin Drug Discov. 13 (4): 295–305. doi:10.1080/17460441.2018.1429400. PMID 29361853.

- ^ Haddad F, Sawalha M, Khawaja Y, Najjar A, Karaman R (December 2017). "Dopamine and Levodopa Prodrugs for the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease". Molecules. 23 (1): 40. doi:10.3390/molecules23010040. PMC 5943940. PMID 29295587.

- ^ a b Salamone JD, Yohn SE, López-Cruz L, San Miguel N, Correa M (May 2016). "Activational and effort-related aspects of motivation: neural mechanisms and implications for psychopathology". Brain. 139 (Pt 5): 1325–1347. doi:10.1093/brain/aww050. PMC 5839596. PMID 27189581.

- ^ a b Brown AS, Gershon S (1993). "Dopamine and depression". J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 91 (2–3): 75–109. doi:10.1007/BF01245227. PMID 8099801.

- ^ Webber HE, Lopez-Gamundi P, Stamatovich SN, de Wit H, Wardle MC (January 2021). "Using pharmacological manipulations to study the role of dopamine in human reward functioning: A review of studies in healthy adults". Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 120: 123–158. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.004. PMC 7855845. PMID 33202256.

- ^ Zénon A, Devesse S, Olivier E (September 2016). "Dopamine Manipulation Affects Response Vigor Independently of Opportunity Cost". J Neurosci. 36 (37): 9516–9525. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4467-15.2016. PMC 6601940. PMID 27629704.

- ^ Salamone JD, Correa M (January 2024). "The Neurobiology of Activational Aspects of Motivation: Exertion of Effort, Effort-Based Decision Making, and the Role of Dopamine". Annu Rev Psychol. 75: 1–32. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-020223-012208. hdl:10234/207207. PMID 37788571.

- ^ Brilliant MH, Vaziri K, Connor TB, Schwartz SG, Carroll JJ, McCarty CA, et al. (March 2016). "Mining Retrospective Data for Virtual Prospective Drug Repurposing: L-DOPA and Age-related Macular Degeneration". The American Journal of Medicine. 129 (3): 292–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.015. PMC 4841631. PMID 26524704.

External links

[edit]- "Levodopa". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.