Adab (city)

Adab | |

| Alternative name | Bismya |

|---|---|

| Location | Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°56′50.1″N 45°37′34.5″E / 31.947250°N 45.626250°E |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1885, 1890, 1902, 1903–1905, 2001, 2016-2019 |

| Archaeologists | W.H. Ward, J.P. Peters, W. Andrae, E.J. Banks, Nicolò Marchetti |

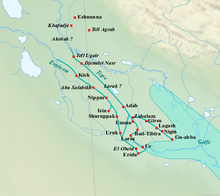

Adab (Sumerian: 𒌓𒉣𒆠 Adabki,[1] spelled UD.NUNKI[2]) was an ancient Sumerian city between Girsu and Nippur, lying about 35 kilometers southeast of the latter. It was located at the site of modern Bismaya or Bismya in the Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate of Iraq. The site was occupied at least as early as the 3rd Millenium BC, through the Early Dynastic, Akkadian Empire, and Ur III empire periods, into the Kassite period in the mid-2nd millennium BC. It is known that there were temples of Ninhursag/Digirmah, Iskur, Asgi, Inanna and Enki at Adab and that the city-god of Adab was Parag'ellilegarra (Panigingarra) "The Sovereign Appointed by Ellil".[3][4]

Not to be confused with the small, later (Old Babylonian and Sassanian periods) archaeological site named Tell Bismaya, 9 kilometers east of the confluence of the Diyala and the Tigris rivers, excavated by Iraqi archaeologists in the 1980s.[5]

Archaeology

[edit]

The 400-hectare site consists of a number of mounds distributed over an area about 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) long and 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) wide, consisting of a number of low ridges, nowhere exceeding 12 metres (39 ft) in height, lying somewhat nearer to the Tigris than the Euphrates, about a day's journey to the southeast of Nippur. It was surrounded by a double wall. In total there are twelve mounds of which two (Mounds X and XII) are the result of sand dredged from the Iturungal canal, though some rooms and 20 tablets were found on the northern extension of X. Persons reported working on mound XIV and mound XVI but there is no record where they lay. Some private houses were noted outside the east wall.[6] Notable mounds were

- Mound I - Palace, Isin/Larsa - Old Babylonian Periods. About 33 meters by 25 meters. Several hundred mostly fragmentary tablets

- Mound II - Cemetery and House by Bath. Seven burials (5 intramural graves, 2 tombs).

- Mound III - Administrative and light industrial near west corner. Early Dynastic, Akkadian, and Ur III levels.

- Mound IV - The Library. Over 2,000 tablets found here. Akkadian period administrative center.

- Mound V - E-Sar/E-mah Temple. Mound 11 meters high and 90 meters in circumference. Ten occupation levels, atop pure sand, ranging from Early Dynastic I to Ur III. Inscribed bricks of Kurigalzu indicated restoration in the Kassite period.

- Mound VI - Large walls with inscribed bricks of Amar-Sin. Thought to be a temple.

Initial examinations of the site of Bismaya were by William Hayes Ward of the Wolfe Expedition in 1885 and by John Punnett Peters of the University of Pennsylvania in 1890, each spending a day there and finding one cuneiform tablet and a few fragments.[7][8] Walter Andrae visited Bismaya in 1902, found a tablet fragment and produced a sketch map of the site.[9]

Excavations were conducted there on behalf of the University of Chicago and led by Edgar James Banks for a total of six months beginning on Christmas Day of 1903 until May 25, 1904. Work resumed on September 19, 1904 but was stopped after 8 1/2 days by the Ottoman authorities. Excavation resumed on March 13, 1905 under the direction of Victor S. Persons and continued until the end of June, 1905. During the excavation of a city gate thousands of sling balls (some stone, most of baked clay), some flattened, were found which the excavator interpreted as the result of a battle. While Banks was better trained than the earlier generation of antiquarians and treasure hunters and used more modern archaeological methods the excavations suffered seriously from having never been properly published.[10][11][12][13] The Banks expedition to Bismaya was well documented by the standards of the time and many objects photographed though no final report was ever produced due to personal disputes. In 2012, the Oriental Institute re-examined the records and objects returned to the institute by Banks and produced a "re-excavation" report. One issue is that Banks and Persons purchase objects from Adab locally while there and it is uncertain which object held at the museum were excavated vs being bought.[6]

On Mound V, on what was originally thought to be an island but has since been understood to have resulted from a shift in the canal bed, stood the temple, E-mah, with a ziggurat. The temple had two occupational phases. E-Sar, the first (Earlier Temple), constructed of plano-convex bricks, was from the Early Dynastic period. That temple was later filled in with mud bricks and sealed off with a course of baked brick and bitumen pavement. A foundation deposit of Adab ruler E-iginimpa'e dated to Early Dynastic IIIa was found on that pavement containing "inscribed adze-shaped copper object (A543) with a copper spike (A542) inserted into the hole at its end and two tablets, one of copper alloy (A1160) and one of white stone (A1159)".[14]

𒀭𒈤 𒂍𒅆𒉏𒉺𒌓𒁺 𒃻𒑐𒋼𒋛 𒌓𒉣𒆠 𒂍𒈤 𒈬𒈾𒆕 𒌫𒁉𒆠𒂠 𒋼𒁀𒋛

d-mah/ e2-igi-nim-pa-e3/ GAR-ensi/ adab{ki}/ e2-mah mu-na-du/ ur2-be2 ki-sze3/ temen ba-si

"For the goddess Digirmah, E-iginimpa'e, ensi-GAR of Adab, built the E-Mah for her, and buried foundation deposits below its base"[15]

The second temple (Later Temple) was faced by baked bricks, some with an inscription of the Ur III ruler Shulgi naming it the temple of the goddess Ninhursag.[16]

Adab was evidently once a city of considerable importance, but deserted at a very early period, since the ruins found close to the surface of the mounds belong to Shulgi and Ur-Nammu, kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur in the latter part of the third millennium BC, based on inscribed bricks excavated at Bismaya. Immediately below these, as at Nippur, were found artifacts dating to the reign of Naram-Sin and Sargon or the Akkadian Empire, c. 2300 BC. Below these there were still 10.5 metres (34 ft) of stratified remains, constituting seven-eighths of the total depth of the ruins. A large palace was found in the central area with a very large well lined with plan-convex bricks, marking it as being from the Early Dynastic period.[17]

Besides the remains of buildings, walls, and graves, Banks discovered a large number of inscribed clay tablets of a very early period, bronze and stone tablets, bronze implements and the like.[6] Of the tablets, 543 went to the Oriental Institute and roughly 1100, mostly purchased from the locals rather than excavated, went to the Istanbul Museum. The latter are still unpublished.[18][19] Brick stamps, found by Banks during his excavation of Adab state that the Akkadian ruler Naram-Sin built a temple to Inanna at Adab, but the temple was not found during the dig, and is not known for certain to be E-shar. The two most notable discoveries were a complete statue in white marble, apparently the earliest yet found in Mesopotamia, now in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, bearing the inscription, translated by Banks as "E-mach, King Da-udu, King of, Ud-Nun", now known as the statue of Lugal-dalu and a temple refuse heap, consisting of great quantities of fragments of vases in marble, alabaster, onyx, porphyry and granite, some of which were inscribed, and others engraved and inlaid with ivory and precious stones.[6][20]

Of the Adab tablets that ended up at the University of Chicago, sponsor of the excavations, all have been published and also made available in digital form online. [21] After the end of excavation, on a later personal trip the region in 1913, Banks purchased thousands of tablets from a number of sites, many from Adab, and sold them sold piecemeal to various owners over years. Some have made their way into publication. Many more have subsequently made their way into the antiquities market from illegal looting of the site and some have also been published.[22] A number ended up in the collection of the Cornell University.[23][24][25][26]

In response to widespread looting which began after the war 1991, the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage conducted an excavation at Adab in 2001.[27] The site has now been largely destroyed by systematic looting which increased after the war in 2003, so further excavation is unlikely. On the order of a thousand tablets from that looting, all from the Sargonic Period, have been sold to various collectors and many are being published, though missing archaeological context. Of the 9,000 published tablets from the Sargonic Period (Early Dynastic IIIb, Early Sargonic, Middle Sargonic and Classic Sargonic) about 2,300 came from Adab.[28]

From 2016 to 2019, the University of Bologna and the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage led by Nicolò Marchetti conducted a program, the Qadis survey, of coordinated remote sensing and surface surveys in the Qadisiyah province including at Bismaya (QD049). Results included a "Preliminary reconstruction of the urban layout and hydraulic landscape around Bismaya/Adab in the ED III and Akkadian periods".[29][30] A previously unknown palace was discovered and the extent of looting identified. It was determined that the city was surrounded by canals. The overall occupation of the site in the Early Dynastic III period was determined to have been 462 hectares.[31] The Qadis survey showed that Adab had a 24-hectare central harbor, with a maximum length of 240 meters and a maximum width of 215 meters. The harbor was connected to the Tigris river via a 100-meter–wide canal.[32][33] In 2001 a statue became available to the Baghdad Museum which was inscribed "Temple Builder, of the goddess Nin-SU(?)-KID(?): Epa'e, King of Adab".[34]

History

[edit]Adab is mentioned in late 4th millennium BC texts found at Uruk but no finds from that period have been recovered from the site.[35]

Early Dynastic Period

[edit]

Adab was occupied from at least the Early Dynastic Period. According to Sumerian text Inanna's descent to the netherworld, there was a temple of Inanna named E-shar at Adab during the reign of Dumuzid of Uruk. In another text in the same series, Dumuzid's dream, Dumuzid of Uruk is toppled from his opulence by a hungry mob composed of men from the major cities of Sumer, including Adab.

A king of Kish, Mesilim, appears to have ruled at Adab, based on inscriptions found at Bismaya. One inscription, on a bowl fragment reads "Mesilim, king of Kish, to Esar has returned[this bowl], Salkisalsi being patesi of Adab".[36] One king of Adab, Lugal-Anne-Mundu, appearing in the Sumerian King List, is mentioned in few contemporary inscriptions; some that are much later copies claim that he established a vast, but brief empire stretching from Elam all the way to Lebanon and the Amorite territories along the Jordan.[37] Adab is also mentioned in some of the Ebla tablets from roughly the same era as a trading partner of Ebla in northern Syria, shortly before Ebla was destroyed by unknown forces.[38]

A marble statue was found at Bismaya inscribed with the name of another king of Adab, variously translated as Lugal-daudu, Da-udu, and Lugaldalu.[39][40] An inscription of Eannatum, ruler of Lagash was also found at Adab.[41]

Sargonic period

[edit]

Meskigal, governor of Adab under Lugalzagesi of Uruk, changed allegiance to Akkad and became governor under Sargon of Akkad. He later joined other cities including Zabalam in a rebellion against Rimush son of Sargon and second ruler of the Akkadian Empire and was defeated and captured. About 380 of the published tablets from Adab date to the time of Meskigal (ED IIIB/Early Sargonic). This rebellion occurred during the first two regnal years of Rimush. A year name of Rimush reads "The year Adab was destroyed" and an inscription reads "Rimus, king of the world, was victorious over Adab and Zabala in battle and struck down 15,718 men. He took 14,576 captives". Various governors, including Lugal-gis, Sarru-alli, Ur-Tur, and Lugal-ajagu then ruled Adab under direct Akkadian control. About 1000 tablets from this period (Middle Sargonic) have been published.[42] In the time of Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin Adab, again joined a "Great Rebellion" against Akkad and was again defeated.[43] In the succeeding period (Classical Sargonic) it is known that there were temples to Ninhursag/Digirmah (E-Mah), Iskur, Asgi, Inanna and Enki. By the end of the Akkadian period, Adab was occupied by the Gutians, who made it their capital.[44] Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon and first known poet, wrote a number of temple hymns including one to the temple of the goddess Ninhursag and her son Ashgi at Adab.[45]

Ur III Empire

[edit]

Several governors of the city under Ur III are also known including Ur-Asgi and Habaluge under Ur III ruler Shulgi (and Amar-Sin) and Ur-Asgi II under Shu-Sin. A brick inscription found at Adab marked Shulgi dedicating a weir to the goddess Ninhursag. Inscribed bricks of Amar-Sin were also found at Adab.[46][47] A temple for the deified Shi-Sin was built at Adab by Habaluge.

"Sü-Sín, beloved of the god Enlil, the king whom the god Enlil lovingly chose in his (own) heart, mighty king, king of Ur, king of the four quarters, his beloved god, Habaluge, governor of Adab, his servant, built for him his beloved temple."[48]

2nd Millennium BC

[edit]About 200 inscribed objects, mainly tablets but also a few bricks and clay sealings, from the Old Babylonian period of the early 2nd millenium BC from Adab are known. The city of Adab is also mentioned in the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1792 – c. 1750 BC).[49] There is a Sumerian language comic tale, dating to the Old Babylonian period, of the Three Ox-drivers from Adab.[50] Inscribed bricks of the Kassite dynasty ruler Kurigalzu I (c. 1375 BC) were found at Adab, marking the last verified occupation of the site.[17]

List of rulers

[edit]The Sumerian King List (SKL) names only one ruler of Adab (Lugalannemundu). The following list should not be considered complete:

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Dynastic IIIa period (c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC) | |||||

| Empire of Lugal-Ane-mundu of Adab (c. 2600 – c. 2340 BC) | |||||

| |||||

|

Lugal-Anne-Mundu 𒈗𒀭𒉌𒈬𒌦𒆕 |

Unclear succession | King of the Four Quarters of the World King of Sumer King of Adab |

Uncertain; this ruler may have fl. c. 2600 – c. 2340 BC sometime during the Early Dynastic (ED) III period (90 years) |

|

| |||||

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Lumma 𒈝𒈠 |

Unclear succession | Governor of Adab | Uncertain; this ruler may have fl. c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC sometime during the Early Dynastic (ED) IIIa period[51] | ||

|

Nin-kisalsi 𒎏𒆦𒋛 |

Unclear succession | Governor of Adab | reigned c. 2500 BC | temp. of: |

| Medurba 𒈨𒄙𒁀 |

Unclear succession | King of Adab | Uncertain; these two rulers may have fl. c. 2600 – c. 2500 BC sometime during the ED IIIa period | temp. of: | |

| Epa'e 𒂍𒉺𒌓𒁺[34] |

Unclear succession | King of Adab | temp. of: | ||

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Early Dynastic IIIb period (c. 2500 – c. 2350 BC) | |||||

|

Lugal-dalu 𒈗𒁕𒇻 |

Unclear succession | King of Adab | r. c. 2500 BC | temp. of: |

| Paraganedu 𒁈𒃶𒉌𒄭 |

Unclear succession | Governor of Adab | Uncertain; this ruler may have fl. c. 2500 – c. 2400 BC sometime during the EDIIIb period | temp. of: | |

|

E-iginimpa'e 𒂍𒅆𒉏𒉺𒌓𒁺 |

Unclear succession | Governor of Adab | r. c. 2400 BC | temp. of: |

| Mug-si 𒈮𒋛 |

Unclear succession | Governor of Adab | r. c. 2400 BC | temp. of: | |

| Ursangkesh | Unclear succession | Uncertain; these two rulers may have fl. c. 2400 – c. 2350 BC sometime during the EDIIIb period | temp. of: | ||

| Enme'annu | Unclear succession | temp. of: | |||

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Proto-Imperial period (c. 2350 – c. 2270 BC) | |||||

| Hartuashgi | Unclear succession | Uncertain; these two rulers may have fl. c. 2350 – c. 2270 BC sometime during the Proto-Imperial period | temp. of: | ||

| Meskigal 𒈩𒆠𒅅𒆷 |

Unclear succession | Vassal governor of Adab under Umma and (later) Akkad | temp. of: | ||

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Akkadian period (c. 2270 – c. 2154 BC) | |||||

| Sarru-alli | Unclear succession | Vassal governor under Akkad | r. c. 2270 BC | temp. of: | |

| Lugal-ajagu 𒈗𒀀𒈬 |

Unclear succession | Vassal governor of Adan under Akkad | r. c. 2250 BC | temp. of: | |

| Lugal-gis 𒈗𒄑 |

Unclear succession | Vassal governor of Adab under Akkad | r. c. 2220 BC | temp. of: | |

| Ur-tur 𒌨𒀭𒌉 |

Unclear succession | Vassal governor of Adab under Akkad | r. c. 2200 BC | temp. of:

| |

| Amar-Suba 𒀫𒍝𒈹[citation needed] |

Unclear succession | Vassal governor of Adab under Akkad | r. c. 2180 BC | temp. of: | |

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Gutian period (c. 2154 – c. 2119 BC) | |||||

|

Urdumu | Unclear succession | Governor of Adab | Uncertain | temp. of: |

| Depiction | Name | Succession | Title | Approx. dates | Notes |

| Ur III period (c. 2119 – c. 2004 BC) | |||||

| Amar-Suba 𒀫𒍝𒈹 |

Unclear succession | Vassal governor of Adab under Ur | Uncertain | temp. of: | |

Gallery

[edit]-

UD-NUN-KI, "City of Adab" on the statue of Lugal-dalu, with rendering in early Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform.

-

Headless votive statue, from Adab, Iraq, early dynastic period. Museum of the Ancient Orient, Turkey

-

Headless votive statue, from Adab, Iraq, early dynastic period. Museum of the Ancient Orient, Istanbul

-

Head of a votive statue, from Adab, Iraq, early dynastic period. Museum of the Ancient Orient, Turkey

-

Game board, Bismaya, mound IVa, Isin-Larsa to Old Babylonian period, 2000-1600 BC, baked clay, Oriental Institute Museum

-

Cuneiform inscription on a statue from Adab, mentioning the name of Lugal-dalu and god ESAR of Adab

-

Headless statue, the name of the deity Ninshubur is mentioned on the right shoulder. From Adab. 2600-2370 BCE. Iraq Museum

-

Plaque with a sexual scene, Bismaya, mound IV, Isin-Larsa to Old Babylonian period, 2000-1600 BC, baked clay, Oriental Institute Museum

-

Akkadian Period, lapis lazuli seal with six-eared hero subduing a lion and a water buffalo, from Bismaya, ca. 2350-2150 BC

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ [1] D. D. Luckenbill, "Old Babylonian Letters from Bismya", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 270–292, 1916

- ^ Jacobsen, Thorkild, "Some Sumerian city-names", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 21.1, pp. 100-103, 1967

- ^ Marchesi, Gianni and Marchetti, Nicolo, "Historical Framework", Royal Statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 97-128, 2011

- ^ Such-Gutiérrez, "Untersuchungen zum Pantheon von Adab im 3. Jt.", AfO 51, pp. 1–44, 2005-6

- ^ "Excavations in Iraq, 1981-82", Iraq, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 199–224, 1983

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Karen (2012). Bismaya: Recovering the Lost City of Adab - Oriental Institute Publications 138 (PDF). Chicago, Ill.: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 9781885923639.

- ^ [2] John Punnett Peters, "Nippur, or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates; the narrative of the University of Pennsylvania expedition to Babylonia in the years 1888-1921", Volume 1, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1897

- ^ [3] John Punnett Peters, "Nippur, or Explorations and Adventures on the Euphrates; the narrative of the University of Pennsylvania expedition to Babylonia in the years 1888-1921", Volume 2, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1897

- ^ Andrae, Walter (1903). "Die Umgebung von Fara und Abu Hatab". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient Gesellschaft. 16: 24–30.

- ^ [4] Edgar James Banks, "Bismya; or The lost city of Adab : a story of adventure, of exploration, and of excavation among the ruins of the oldest of the buried cities of Babylonia", G. P Putnam's Sons, New York, 1912

- ^ [5] Banks, E. J., and Robert Francis Harper, "Report No. 23 from Bismya", The Biblical World 24.3, pp. 216-218, 1904

- ^ [6] Banks, Edgar James, "Plain Stone Vases from Bismya", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 35–40, 1905

- ^ [7] Edgar James Banks, "The Oldest Statue in the World", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 57–59, Oct 1904

- ^ Tsouparopoulou, Christina, "Hidden messages under the temple: Foundation deposits and the restricted presence of writing in 3rd millennium BCE Mesopotamia", Verborgen, unsichtbar, unlesbar – zur Problematik restringierter Schriftpräsenz, edited by Tobias Frese, Wilfried E. Keil and Kristina Krüger, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 17-32, 2014

- ^ Douglas Frayne, "Adab", Presargonic Period: Early Periods, Volume 1 (2700-2350 BC), RIM The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia Volume 1, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 17-34, 2008 ISBN 978-1-4426-9047-9

- ^ [8] Edgar James Banks, "The Bismya Temple", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 22, vo. 1, pp. 29–34, Oct. 1905

- ^ a b [9] Banks, E. J., and Robert Francis Harper, "The Latest Reports from the Excavations at Bismya", The Biblical World 24.2, pp. 137-146, 1904

- ^ Such-Gutiérrez, M., et al., "Der Kalendar von Adab im 3. Jahrtausend", RAI, iss. 56, pp. 325-340, 2013

- ^ Yang, Chih (1989). Sargonic inscriptions from Adab. Changchun: Institute for the History of Ancient Civillizations. OCLC 299739533.

- ^ [10] Harper, Robert Francis, and E. J. Banks, "Reports No. 24 and 25 from Bismya", The Biblical World 24.5, pp. 377-384, 1904

- ^ [11] Daniel David Luckenbill, "Cuneiform Series, Vol. II: Inscriptions from Adab", Oriental Institute Publications 14, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1930

- ^ Widell, Magnus (2002). "A Previously Unpublished Lawsuit from Ur III Adab" (PDF). Cuneiform Digital Library Journal. 2.

- ^ Maiocchi, Massimo, "Classical Sargonic tablets chiefly from Adab in the Cornell University collections", CUSAS 13, vol. 13. CDL Press, 2009 ISBN 978-1-934309-12-4

- ^ Maiocchi, M. Visicato, G., "Classical Sargonic Tablets Chiefly from Adab in the Cornell, University Collections. Part II", CUSAS 19, Bethesda, 2012

- ^ Pomponio, Francesco Vincenzo, and Giuseppe Visicato, "Middle Sargonic tablets chiefly from Adab in the Cornell University collections", Vol. 20, CDL Press, 2015

- ^ Visicato, Giuseppe, and Aage Westenholz, "Early dynastic and early Sargonic tablets from Adab in the Cornell University collections", Vol. 11, CDL Press, 2010

- ^ Al-Doori, R.; AL - Qaisi, R.; Al-Sarraf, S.; Al-Zubaidi., A.A (2002). "The final report of Basmaia excavations (first season)". Sumer. 51: 58–72.

- ^ Pomponio, Francesco Vincenzo, "Le tavolette cuneiformi di Adab. Le tavolette cuneiformi di varia provenienzia. (Le tavolette cuneiformi delle collezioni della Banca d'Italia 1 & 2)", Banca d'Italia, Roma, 2006

- ^ [12] Marchetti, Nicolò, et al., "New Results on Ancient Settlement Patterns in the South-Eastern Qadisiyah Region (Iraq). the 2016-2017 Iraqi-Italian Qadis Survey Project", Al-Adab Journal 123, pp. 45-62, 2017

- ^ [13] Marchetti, Nicolò, et al., "The rise of urbanized landscapes in Mesopotamia: The QADIS integrated survey results and the interpretation of multi-layered historical landscapes" Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie 109.2, pp. 214-237, 2019

- ^ [14] Marchetti, Nicolò, and Federico Zaina. "Rediscovering the Heartland of Cities", Near Eastern Archaeology 83, pp. 146-157, 2020

- ^ Mantellini, Simone; Picotti, Vincenzo; Al-Hussainy, Abbas; Marchetti, Nicolò; Zaina, Federico (2024). "Development of water management strategies in southern Mesopotamia during the fourth and third millennium B.C.E." Geoarchaeology. 39 (3): 268–299. Bibcode:2024Gearc..39..268M. doi:10.1002/gea.21992. hdl:11585/963863.

- ^ Marchetti, N., Campeggi, M., D'Orazio, C., Gallerani, V., Giacosa, G., Al-Hussainy, A., Luglio, G., Mantellini, S., Mariani, E., Monastero, J., Valeri, M., & Zaina, F., "The Iraqi-Italian Qadis project: Report on six seasons of integrated survey", Sumer, LXVI, pp. 177–218, 2020

- ^ a b al-Mutawalli, Nawala and Miglus, Peter A., "Eine Statuette des Epa’e, eines frühdynastischen Herrschers von Adab", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 3-11, 2002

- ^ Nissen, Hans J., "The Archaic Texts from Uruk", World Archaeology, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 317–34, 1986

- ^ [15] Luckenbill, D. D., "Two Inscriptions of Mesilim, King of Kish", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 219-223, 1914

- ^ [16] Chen, Yanli, and Yuhong Wu., "The Names of the Leaders and Diplomats of Marḫaši and Related Men in the Ur III Dynasty", Cuneiform Digital Library Journal 2017 (1), 2017

- ^ Cyrus H. Gordon and Gary A. Rendsburg eds, "Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 3", Eisenbrauns, 1992 ISBN 978-0-931464-77-5

- ^ [17] G.A. Barton, "The Names of Two Kings of Adab", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 33, pp. 295—296, 1913

- ^ [18] Banks, Edgar James, "Statue of the Sumerian King David", Scientific American 93.8, pp. 137-137, 1905

- ^ Curchin, Leonard, "Eannatum and the Kings of Adab", Revue d’Assyriologie et d’archéologie Orientale, vol. 71, no. 1, pp. 93–95, 1977

- ^ a b [19] Douglas R. Frayne, "Adab", The Sargonic and Gutian Periods (2334–2113), University of Toronto Press, pp. 252-258, 1993 ISBN 0-8020-0593-4

- ^ Steve Tinney, A New Look at Naram-Sin and the "Great Rebellion", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 47, pp. 1-14, 1995

- ^ [20] M. Molina, "The palace of Adab during the Sargonic period", D. Wicke (ed.), Der Palast im antiken und islamischen Orient, Colloquien der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 9, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 151-20, 2019

- ^ Helle, Sophus, "Enheduana: The Complete Poems of the World's First Author", New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023 ISBN 978-0300264173

- ^ "Frayne, Douglas, "Šulgi E3/2.1.2", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 91-234, 1997

- ^ Ozaki, Tohru, "Who was the Successor of Habaluge, ensi₂ of Ur III Adab?", Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 117.1, pp. 23-28, 2023

- ^ "Frayne, Douglas, "Šū-Sîn E3/2.1.4", Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 285-360, 1997

- ^ [21]"RIME 4.03.06.Add21 (Laws of Hammurapi) Composite Artifact Entry", (2014) 2024. Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI). July 11, 2024

- ^ Alster, Bendt (1991). "The Sumerian Folktale of the Three Ox-Drivers from Adab". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 43/45: 27–38. doi:10.2307/1359843. ISSN 0022-0256. JSTOR 1359843. S2CID 163369801.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Marchesi, Gianni (January 2015). Sallaberger, Walther; Schrakamp, Ingo (eds.). "Toward a Chronology of Early Dynastic Rulers in Mesopotamia". History and Philology (ARCANE 3; Turnhout): 139–156.

- ^ Molina, M. 2014: Sargonic Cuneiform Tablets in the Real Academia de la Historia: The Carl L. Lippmann Collection (with the collaboration ofM .E. Milone andE. Markina). Catálogo del Gabinete de Antigüedades 1.1.6. Madrid

Further reading

[edit]- Abid, Basima Jalil, and Hayder Aqeel Abed Al-Qaragholi, "The Hybrid Animal (šeg9-bar) Unpublished Cuneiform Texts from Akkadian Period from Adab city", ISIN Journal 4, pp. 77–87, 2022

- [22] Banks, Edgar James, "Inlaid and Engraved Vases of 6500 Years Ago.(Illustrated.)", The Open Court, 11: 4, pp. 685–693, 1906

- [23] Banks, Edgar James, "The Statue of King David and What it Teaches-(Illus.)", The Open Court, 4: 3, pp. 212–219, 1906

- Cooper, Jerrold S., "Studies in Mesopotamian Lapidary Inscriptions IV: A Statuette from Adab in the Walters art gallery", Oriens Antiquus 23, pp. 159–61, 1984

- Farber, Walter, "Two Old Babylonian Incantation Tablets, Purportedly from Adab (A 633 and A 704)", Mesopotamian Medicine and Magic, Brill, pp. 189–202, 2018

- Kraus, F. R., "Briefe aus dem Istanbuler Museum", Altbabylonische Briefe in Umschrift und Übersetzung 5, leiden:Brill, 1972

- Langdon, S., "Ten Tablets from the Archives of Adab", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale 19.4, pp. 187–194, 1922

- Maiocchi, Massimo, "The Sargonic Archive of Me-sá-sag7, Cup-bearer of Adab", City Administration in the Ancient Near East. Proceedings of the 53e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, vol. 2., Eisenbrauns, pp. 141–152, 2010

- Maiocchi, Massimo, "Women and Production in Sargonic Adab", The Role of Women in Work and Society in the Ancient Near East, edited by Brigitte Lion and Cécile Michel, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 90–111, 2016

- Caroline Nestmann Peck, "The Excavations at Bismaya", Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago, 1949

- Pomponio, F., "The Rulers of Adab", in Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. History & Philology, W. Sallaberger and I. Schrakamp (eds.), ARCANE 3, Turnhout, pp. 191–195, 2015

- Sallaberger, W., "The Palace and the Temple in Babylonia", in G. Leick (ed.), The Babylonian World, Oxon 1 New York, pp. 265–275, 2007

- Visicato, G., "New Light from an Unpublished Archive of Meskigalla, Ensi of Adab, Housed in the Cornell University Collections", in L. Kogan et al. (eds.), City Administration in the Ancient Near East. Proceedings of the 53e Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale. 2. Babel und Bibel5, Winona Lake, pp. 263–271, 2010

- Karen Wilson, "The Temple Mound at Bismaya", in Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen, Penn State University Press, pp. 279–99, 2002 ISBN 978-1-57506-055-2

- Yang Zhi, "The Excavation of Adab", Journal of Ancient Civilizations, Vol. 3, pp. 16–19, 1988

- Zhi, Yang, "A study of the Sargonic Archive from Adab", Dissertation, The University of Chicago, 1986

- Zhi, Yang, "The King Lugal-ane-mundu", Journal of Ancient Civilizations 4, pp. 55–60, 1989

- Zhi, Yang, "The Name of the City Adab", Journal of Ancient Civilizations 2, pp. 121–25, 1987