Aung San

Aung San | |

|---|---|

အောင်ဆန်း | |

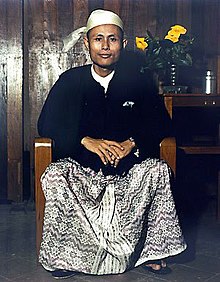

Aung San, c. 1940s | |

| Premier of British Burma | |

| In office 28 September 1946 – 19 July 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Sir John Wise |

| Succeeded by | U Nu |

| Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of War of the State of Burma | |

| In office 1 August 1943 – 27 March 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Chairman of the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League | |

| In office 27 March 1945 – 19 July 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | U Nu |

| General Secretary of Communist Party of Burma | |

| In office 15 August 1939 – 1940 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Thakin Soe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Htein Lin 13 February 1915 Natmauk, Magwe, British Raj |

| Died | 19 July 1947 (aged 32) Rangoon, British Burma |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Resting place | Martyrs' Mausoleum, Myanmar |

| Political party | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 4, including Aung San Oo and Aung San Suu Kyi |

| Relatives |

|

| Alma mater | Rangoon University |

| Occupation | Politician, soldier |

| Known for | His work towards Burmese independence and the establishment of the Tatmadaw |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Major general (highest rank in military at that time) |

Bogyoke Aung San (Burmese: ဗိုလ်ချုပ် အောင်ဆန်း; MLCTS: aung hcan:, pronounced [àʊɰ̃ sʰáɰ̃]; 13 February 1915 – 19 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goal was realized. Aung San is considered to be the founder of modern-day Myanmar and the Tatmadaw (the country's armed forces), and is commonly referred to by the titles "Father of the Nation", "Father of Independence", and "Father of the Tatmadaw".

Devoted to ending British Colonial rule in Burma, Aung San founded or was closely associated with many Burmese political groups and movements and explored various schools of political thought throughout his life. He was a life-long anti-imperialist and studied socialism as a student. In his first year of university he was elected to the executive committee of the Rangoon University Students' Union and served as the editor of its newspaper. He joined the Thakin Society in 1938 and served as its general secretary. He also helped establish the Communist Party of Burma in 1939 but quit shortly afterwards due to vehement disagreements with the rest of the party leadership. He subsequently co-founded the People's Revolutionary Party (later the Burma Socialist Party) with the primary goal of Burmese independence from the British.

Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, Aung San fled Burma and went to China to solicit foreign support for Burmese independence. During the Japanese occupation of Burma, he served as the minister of war in the Japan-backed State of Burma led by Dr. Ba Maw. As the tide turned against Japan, he switched sides and merged his forces with the Allies to fight against the Japanese. After World War II, he negotiated Burmese independence from Britain in the Aung San-Attlee agreement. He served as the 5th Premier of the British Crown Colony of Burma from 1946 to 1947. He led his party, the Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League, to victory in the 1947 Burmese general election, but he and most of his cabinet were assassinated shortly before the country became independent.

Aung San's daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi, is a stateswoman, politician, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. She was Burma's State Counsellor and its 20th (and first female) Minister of Foreign Affairs in Win Myint's Cabinet until the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état.

Early life and education

[edit]Aung San was born in Natmauk, Magway District, on 13 February 1915 during the British Raj. The family was considered middle-class.[1] He was the youngest of nine siblings; he had three older sisters and five older brothers.[2] Aung San's name was given to him by his brother Aung Than. Aung San received his primary education at a Buddhist monastic school in Natmauk, but he moved to Yenangyaung in grade 4 because his eldest brother, Ba Win, had become the principal of the high school there.[3]

Aung San rarely spoke before the age of eight. As a teenager, he often spent hours reading and thinking alone, oblivious to those around him. In his youth he was generally unconcerned with his appearance and clothing. In his earliest articles, published in the "Opinion" section of The World of Books, he opposed the ideology of Western-style individualism supported by U Thant in favour of a social philosophy based on the "standardization of human life". Aung San later became friends with U Thant through their mutual friendship with U Nu.[4]

University years

[edit]

After Aung San entered Rangoon University in 1933, he quickly became a student leader.[5] He was elected to the executive committee of the Rangoon University Students' Union (RUSU). He then became editor of the RUSU's magazine Oway (Peacock's Call).[6] Aung San was described by contemporary students as being charismatic and keenly interested in politics.[1]

In February 1936 he was expelled from the university, along with U Nu, for refusing to reveal the name of the author of an article he had run in the student newspaper called "Hell Hound at Large", which criticized a senior university official.[7] The expulsion led to the three-month long Second University Students' Strike, after which the university authorities reinstated Aung San and Nu.[8]

The events of 1936 had a profound effect on the future of Aung San. Before 1936 he was not well known outside of Rangoon University, but during the student strike his name and image were published and discussed in daily newspapers, and he became known nationwide as a nationalist revolutionary and a student leader. He also served in his first student leadership positions, first as secretary of the student boycott council and second as the student representative for the government's University Act Amendment Committee, which the government formed in response to the strike. Later in 1936, after the student strike was over, he was elected the vice president of the Rangoon University Student Union. Because of his participation in the student strike he was not able to sit for the examination in 1936, and received his Bachelor of Arts in 1937.[9]

After his graduation Aung San began studying for a law degree. His intention at the time was to "take a shot at the examinations for the Indian Civil Service ... and go into politics". Along with other student leaders he founded the All Burma Student Union (later known as All Burma Federation of Student Unions) in 1937, in which he was elected general secretary. In 1938 he became the president of both the All Burma Student Union and the Rangoon University Student Union, but his pursuit of these commitments did not leave him enough time to study, and he failed his examination in 1938. After 1938 he resolved to abandon the pursuit of a conventional career and committed himself to revolutionary politics.[10]

Thakin revolutionary

[edit]In October 1938, Aung San left his law classes and entered national politics. At this point, he was anti-British and staunchly anti-imperialist. He became a Thakin ("lord" or "master": a title often used as an informal title for Westerners in Burma; the usage by Burmese proclaimed that the Burmese people were the true masters of their country) when he joined the Dobama Asiayone ("We Burmans Association"). He acted as its general secretary until August 1940. While in this role, he helped organize a series of countrywide strikes that became known as the ME 1300 Revolution. The name of this movement was based on the Burmese calendar year 1300: in the Western calendar this year occurred between August 1938 and July 1939.[11]

On 18 January 1939 the Dobama Asiayone declared its intention to use force in order to overturn the government, leading the authorities to crack down on the organization. On 23 January Police raided their headquarters at Shwedagon Pagoda, arrested Aung San, and held him in prison for fifteen days on charges of conspiracy to overthrow the government, but these charges were dropped.[12] Upon his release Aung San proposed a strategy of pursuing Burmese independence by staging countrywide strikes, anti-tax drives, and guerrilla insurgency.[13]

In August 1939, Aung San became a founding member and the first Secretary General of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB). Aung San later claimed that his relationship with the CPB was not smooth, since he joined and left the party twice. Shortly after founding the CPB, Aung San founded a similar organization, alternatively known as either the "People's Revolutionary Party" or the "Burma Revolutionary Party". This party was Marxist, formed with the goal of supporting Burmese independence against the British. It survived and was reformed into the Burma Socialist Party following World War II.[14]

Aung San was not paid for most of his work as a student or political leader, and lived for most of this time in a state of poverty. He was recognized by his peers for his strong work ethic and organizational skills, but was sometimes criticized by them for having poor public relations skills or for a perceived arrogance. He never drank alcohol and abstained from romantic relationships.[15]

World War II

[edit]Following the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, Aung San helped to found another nationalist organization, the Freedom Bloc, by forming an alliance between the Dobama, the All Burma Students Union, politically active monks, and Dr. Ba Maw's Poor Man's Party.[16] Dr. Ba Maw served as the anarshin ("dictator") of the Freedom Bloc, while Aung San worked under him as the group's general secretary. The group's goals were organized around the idea of taking advantage of the war to gain Burmese independence.[17] The organization, goals, and tactics of the Freedom Bloc were modeled on the Indian revolutionary group "Forward Bloc", whose leader, Subhas Chandra Bose, was in regular contact with Ba Maw.[18] In 1939, Aung San was briefly arrested on the grounds of conspiring to overthrow the government by force, but was released[13] after seventeen days.[19] Upon his release Aung San proposed a strategy of pursuing Burmese independence by staging countrywide strikes, anti-tax drives, and guerrilla insurgency.[13]

In March 1940, he attended an Indian National Congress Assembly in Ramgarh, India,[7] along with other Thakins, including Than Tun and Ba Hein. While there, Aung San met many leaders of the Indian independence movement, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi, and Subhas Chandra Bose.[20] When Aung San returned to Burma, he found the Burmese government had issued a warrant for his arrest, and the arrest of many other leaders of the Thakins and the Freedom Bloc, due to those organizations' efforts to organize a revolution against the British, at least partially with Japanese support.[21][19][20]

Besides his other warrants, the district superintendent of Henzada, a man named "Xavier", had issued a reward of 500 rupees for anyone who could capture Aung San. Some of Aung San's colleagues advised him to go to the Shanghai International Settlement and make contact with communist agents there, but he was in a hurry to leave and was unable to find passage on a ship travelling to that city.[19] On 14 August 1939, Aung San and another Thakin colleague, Hla Myaing, boarded the Norwegian cargo ship Hai Lee to Xiamen, China.[20] Neither Aung San nor Hla Myaing gave their real names, identifying themselves as "Tan Luang Shun" and "Tan Su Taung".[19] They wandered the city for several weeks with no precise plan and little money, until they were intercepted by Japanese secret police who convinced them to go to Japan instead.[13] The pair left for Tokyo via Taiwan and arrived in Japan on 27 September 1940.[20]

Formation of the Thirty Comrades

[edit]In May 1940 Japanese intelligence officers led by Suzuki Keiji had arrived in Yangon posing as journalists in order to gather information and to seek the cooperation of local parties for the intended Japanese invasion of Burma, occupying an office at 40 Judah Ezekiel Street for that purpose. Among their network of local collaborators they made close connections with the Thakins, of which Aung San was a leading member. The familiarity of Japanese intelligence with prominent political actors in Burma ensured that they were aware of Aung San's activities by the time he arrived in Japanese-occupied China.[22]

Aung San spent the rest of 1940 in Tokyo, learning the Japanese language and political ideology. At the time he wrote that he was opposed to Western individualism and that he intended to create an authoritarian state modelled on Japan with "one state, one party, [and] one leader".[citation needed] While in Japan he dressed in a Japanese Kimono and adopted a Japanese name, "Omoda Monji".[23] During this time the Blue Print for a Free Burma was drafted. This document has been attributed to Aung San,[24] though its authorship is disputed.[25]

In February 1941 Aung San, working with Japanese intelligence, left Hla Myaing in Bangkok[26] and secretly re-entered Burma and began efforts to contact and recruit additional Burmese agents to work with the Japanese. He entered the colony secretly through the port of Bassein, changed into a longyi, and booked a train to Rangoon using a pseudonym. Within weeks he had recruited thirty of his old revolutionary colleagues and smuggled them out of the country via Japanese intelligence networks. These "Thirty Comrades" were taken to the Japanese-occupied island of Hainan for further training. Aung San was twenty-five, the third-oldest of the group. While training on Hainan all thirty of the men took pseudonyms beginning with the word "Bo", meaning "officer", which had become a title used by Westerners in Burma. Aung San took the nom de guerre "Bo Teza" ("Teza" means "fire"). The Thirty Comrades trained for six months on Hainan with Suzuki Keiji and other Japanese officers. Aung San, Ne Win, and Setkya all received special training, since the Japanese intended to place them in senior positions in the Burmese government following the Japanese conquest of the territory.[23]

Japanese invasion and wartime administration

[edit]

Between November and December 1941 Aung San and his party were successful in recruiting approximately 3,500 Burmese volunteers from the Siam-Burma border to serve in their army. On 28 December 1941, Aung San and the rest of the Thirty Comrades formally inaugurated the Burma Independence Army in Bangkok.[24] The event involved the thwe thauk ("blood drinking") ceremony, a tradition inherited from the Burmese aristocracy.[27] The participants collected their blood from a cut in their arms, mixing the participants' blood together with alcohol in a silver bowl, and drinking it while pledging eternal comradeship and loyalty. Three days later the BIA entered Burma behind the invading Japanese Fifteenth Army.[24] The BIA left most of the fighting to the Japanese Army but occupied the areas behind Japanese lines after the British had retreated. The arrival of BIA units in many areas of Burma was followed by escalating communal violence, especially against Karen people and others who held privileged positions and whom they believe to have oppressed the Buddhist Burmese during the British administration. The violence lasted for several weeks until the Japanese Army intervened.[28]

The capital of Burma, Rangoon, fell to the Japanese as part of the Burma Campaign in March 1942. The BIA formed an administration for the country under Thakin Tun Oke that operated in parallel with the Japanese military administration until the Japanese disbanded it. In July, the disbanded BIA was re-formed as the Burma Defense Army (BDA). Aung San was made a colonel and put in charge of the force.[7] He was later invited back to Japan, and was presented with the Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Hirohito.[7]

On 1 August 1943, the Japanese held an independence ceremony in Rangoon, in which they formally granted Burma independence on condition that it would be under a wartime administration for the duration of the war. Burma was also required to declare war on the Allies. The Japanese had planned to make Aung San the leader of the country, but in the end they were more impressed with Dr. Ba Maw, and made him the leader instead, giving him virtually dictatorial control under their direction. Aung San was made the second most powerful person in the government. The government was modelled after Japan, and intentionally eschewed democratic principles and patterns of government. The army, still under the control of Aung San, took their motto, "One Blood, One Voice, One Command" at this time. It is still the official motto of the Burmese military.[29]

As the tide of war turned against Japan, Aung San was increasingly skeptical of Japan's ability to win the war and made plans to organize an anti-Japanese uprising in Burma, secretly forming the "Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League" in August 1944. He organized a secret meeting in Bago between the Burma National Army, the Communist Party of Burma, and the People's Revolutionary Party (which later reformed into the Burma Socialist Party).[30] After this meeting, Aung San's forces began to secretly store supplies in preparation of their fight against the Japanese. In late March 1945, as Allied forces advanced towards Rangoon, Aung San led the BNA in a parade in front of Government House in Rangoon, after which they were sent by the Japanese to the front. A few days later, on 27 March, the BNA switched sides and attacked the Japanese instead.[31] 27 March came to be commemorated as Resistance Day, until the military regime renamed it "Tatmadaw (Armed Forces) Day".

After the Burmese army began the attack on the Japanese, it was renamed the "Patriotic Burmese Forces" and its command structure was divided into eight different regions. Aung San was given command of the first region, comprising the areas of Prome, Henzada, Tharrawaddy, and Insein. His designated political advisor was Thakin Ba Hein, a Communist Party leader. On 30 March, the Allied commander in Southeast Asia, Louis Montbatten, formally recognized the Burmese army as "an Allied force".[32]

The Burmese National Army continued to harass the Japanese throughout the remainder of the war. When Allied forces retook Rangoon on 2 May 1945, the BNA were symbolically sent into the city two days before any other soldiers. The Allies helped to arm Aung San's forces somewhat after their defection, supplying the BNA with 3,000 small arms.[33]

Aung San first met with General Bill Slim on 16 May 1945, appearing unexpectedly in Slim's camp in the uniform of a Japanese major general. At the meeting Aung San stated his intentions to ally with the British until the Japanese had been driven out of Burma, and agreed to incorporate his forces into Slim's British-led army. When Slim asked Aung San whether he was taking a risk by unexpectedly coming to his camp in the uniform of a Japanese officer and adopting a bold attitude, Aung San answered that he was not, "because you are a British officer." Slim later wrote that Aung San had made a good impression in the meeting.[34]

Post World War II

[edit]

World War II ended on 12 September 1945. Following the end of the war the Burma National Army was renamed the Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF), and then gradually disarmed by the British as the Japanese were driven out of various parts of the country.

The leaders of the Patriotic Burmese Forces, while disbanded, were offered positions in the Burma Army under British command according to the Kandy conference agreement with Lord Louis Mountbatten in Ceylon in September 1945. Aung San was not invited to negotiate, since the British Governor General, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, was debating whether he should be put on trial for his role in the public execution of a Muslim headman in Thaton during the war. Aung San was never tried or faced any consequence for the execution of the village headman.[35] The delegates agreed that the new Burmese army would be composed of 5,000 of Aung San's Japanese-trained Bamar soldiers, and 5,000 British-trained soldiers, most of whom were either Chin, Kachin, or Karen.[36] Aung San wrote to U Seinda in Arakan, saying that he supported U Seida's guerrilla fight against the British, but that he would cooperate with them for tactical reasons. After the Kandy Conference, he reorganized his formally disbanded soldiers as a paramilitary organization the People's Volunteer Organization (PVO), which continued to wear uniforms and drill in public. The PVO was personally loyal to Aung San and his party rather than the government. By 1947, the PVO had over 100,000 members.[37] In January 1946 a victory festival was held in the Kachin capital of Myitkyina. Governor Dorman-Smith was invited to attend, but neither Aung San nor anyone from his party were, due to "their connection with the Burma Independence Army".[38]

In an audacious move, Aung San turned himself in for the execution of the village headman. As arresting him would mean a nationwide armed rebellion by the PVO, Dorman-Smith was replaced by a new Governor General of Burma, Sir Hubert Rance. Rance agreed to recognize and negotiate directly with Aung San, possibly to distance them both from the Communist Party of Burma. He also agreed to appoint Aung San to the position of counselor for defense on the Executive Council (a provisional cabinet made in lieu of the upcoming Burmese national election). On 28 September 1946, Aung San was appointed to the even higher position of deputy chairman, making him effectively the 5th Prime Minister of the British-Burma Crown Colony.[39] Aung San had at first worked closely with the Communist Party of Burma, but after they began criticizing him for working with the British he banned all communists from his Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League on 3 November 1946.[40]

Aung San-Attlee agreement and the Panglong Conference

[edit]Aung San was to all intents and purposes Prime Minister, although he was still subject to a British veto. British Prime Minister Clement Attlee invited Aung San to visit London in 1947 in order to negotiate the conditions of Burmese independence.[27] At a press conference during a stopover in Delhi,[7] while on the way to meet Attlee in London,[40] he stated that the Burmese wanted "complete independence" and not dominion status, and that they had "no inhibitions of any kind" about "contemplating a violent or non-violent struggle or both" in order to achieve it. He concluded that he hoped for the best, but was prepared for the worst.[7] He arrived in Britain by air in January 1947 along with his deputy Tin Tut, who he considered his brightest official. Attlee and Aung San signed their agreement on the terms of Burmese independence on 27 January: following the Burmese election in 1947 Burma would join the British Commonwealth (like Canada and Australia), though its government would have the option to leave; its government would control the Burmese Army once Allied armies had withdrawn; a constitutional assembly would be drawn up as soon as possible, with the resulting constitution presented to the British parliament as soon as possible; and Britain would nominate Burma's entrance into the newly founded United Nations.[27] The agreement was not unanimous: two other delegates who attended the conference, U Saw and Thakin Ba Sein, refused to sign it, and it was denounced in Burma by Aung San's critics, including Than Tun and Thakin Soe. No delegates representing Burma's ethnic minorities were present, and both Karen and Shan leaders sent messages warning that they would not consider any agreement signed at the conference legally binding to their communities.[41]

Two weeks after the signing of the agreement with Britain, Aung San signed an agreement at the second Panglong Conference on 12 February 1947, with leaders representing the Shan, Kachin, and Chin peoples. In this agreement these leaders agreed to join a united independent Burma, under the condition that they would have "full autonomy"[42] and the right to secede in 1958, after ten years. Karen leaders were not consulted and were not a part of the agreement. They hoped for a separate Karen State within the British Empire.[43] The date of the signing of the Panglong Agreement has been celebrated in Burma as "Union Day", even though Ne Win effectively dissolved any agreement with Burma's minority communities following his coup in 1962.[44][45]

The general election held in April 1947 was not ideal; the Karens,[43] Mon,[46] and most of Aung San's other political opponents boycotted the process. Since they ran virtually unopposed, every delegate in Aung San's party was elected.[43] In the end Aung San's AFPFL won 176 out of the 210 seats in the Constituent Assembly, while the Karens won 24, the Communists 6, and the Anglo-Burmans 4.[47] In July, Aung San convened a series of conferences at Sorrenta Villa in Rangoon to discuss the rehabilitation of Burma.

Following the 1947 election Aung San began to form his own cabinet. In addition to ethnic Burmese statesmen like himself and Tin Tut, he also persuaded the Karen leader Mahn Ba Khaing, the Shan chief Sao Hsam Htun, and the Bamar leader U Razak (who was of Tamil ancestry) to join his cabinet. No Communists were invited to participate.[48]

Assassination

[edit]In the final years of the British administration of Burma, Aung San became good friends with the penultimate Governor of Burma, Colonel Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, an Anglo-Irishman with whom he would regularly discuss his personal difficulties. In early 1946, approximately a year before his death, Aung San complained to Dorman-Smith that he felt melancholic, that he did not feel close to his old friends in the Burmese military, that he had many enemies, and that he was worried that someone would attempt to assassinate him soon.[49]

A little after 10:30 AM on 19 July 1947, a single army jeep carrying gunmen in military fatigues drove into the courtyard of the Secretariat Building, where Aung San was having a meeting with his new cabinet. There was no wall or gate protecting the government building,[48] and although Aung San had been warned that someone may have been plotting to kill him[50] the sentries guarding the building did not challenge or stop the car in any way.[48] Four men from the car, armed with three Tommy Guns, a Sten gun,[51] and grenades, ran up the stairs towards the council chamber, shot the guard standing outside, and burst into the council chamber.[48] The gunmen shouted, "Remain seated! Don't move!"[50] Aung San stood up and was immediately shot in the chest, killing him. The gunmen sprayed the area where he was standing with gunfire for approximately thirty seconds, killing four other council members immediately and mortally wounding another three. Only three in the room survived.[48]

In addition to Aung San, eight other people were killed, seven of whom were also politicians. Thakin Mya was a minister without portfolio who had been a student leader and a close friend of Aung San. Ba Choe, the minister of information, had been the editor of a prominent nationalist journal. Abdul Razak, a Tamil Muslim, the minister of education, had been a headmaster. Ba Win, the minister of trade, was Aung San's older brother. Mahn Ba Khaing, the minister of industry, was one of the few Karen politicians not to have boycotted involvement in the new government. Sao Sam Htun, the minister of the Hill Regions, was a Shan prince who had taken an active lead in convincing the other ethnic minorities to join Burma in becoming independent. Ohn Maung was a deputy minister in the ministry of transportation who had just entered the conference room to deliver a report before the assassination. Abdul Razak's 18-year-old bodyguard, Ko Htwe, was killed before the gunmen entered the room.[52]

Aftermath

[edit]Burma's last pre-World War II Prime Minister, U Saw (who had himself lost an eye surviving an assassination attempt in late 1946),[27] was arrested for the murders the same day.[53] U Saw was subsequently tried and hanged for his responsibility in the assassination, but there have been many other claims of responsibility from multiple parties ever since Aung San's death. Some claimed that a rogue faction in the British intelligence service was responsible.[54]

Besides Aung San, most of his cabinet, and U Saw, there were a number of other assassinations and attempted assassinations carried out against other men who had been close to Aung San at that time. Two of these included Aung San's English lawyer, Frederick Henry, who was murdered in his house, and F. Collins, a private detective who was investigating Aung San's assassination. According to General Kyaw Zaw, these murders were evidence that somebody was trying to cover up their involvement in the assassination.[55] In September 1948, nine months after Burma's independence, somebody assassinated Tin Tut, who had been one of Aung San's closest advisors and who at the time was Burma's first foreign minister, by throwing a grenade into his car. The assassins were never caught and nobody was ever charged with his murder.[56]

British involvement

[edit]A theory that the British were involved in Aung San's assassination was investigated in a documentary broadcast by the BBC on the 50th anniversary of the assassination in 1997. What did emerge in the course of the investigations at the time of the trial was that several low-ranking British officers had sold firearms to a number of Burmese politicians, including U Saw. Shortly after U Saw's conviction, Captain David Vivian, a British Army officer, was sentenced to five years' imprisonment for supplying U Saw with weapons. Vivian was freed from prison when Karen soldiers captured Insein Prison in May 1949. According to General Kyaw Zaw he then lived with the Karen people in Kawkareik until 1950, when he traveled back to Thailand and then to England, where he lived until his death in 1980. Little information about his motives was revealed either during or after the trial.[51]

Kin Oung, the son of the deputy police inspector who arrested U Saw, claimed that U Saw bought the arms found at his house from the black market after they had been sold by British soldiers, not by the soldiers directly. Kin Oung claimed that the arms, before being smuggled into the black market, were in the process of being transported to Singapore in preparation for their withdrawal from Burma, so U Saw's possession of these weapons was not necessarily evidence of British complicity in Aung San's murder but rather the greed of the individual soldiers. He identified the officer responsible for selling the arms as Major Lance Dane, but claimed that Dane and his associates were later "secretly released" after being imprisoned. Kin Oung claimed that the name of one of Aung San's assassins was "Yan Gyi Aung".[57]

Ancestry

[edit]Aung San's parents were U Phar and Daw Su. U Phar was a lawyer who was described by others as introverted and reserved. According to Aung San, U Phar studied law and passed his bar exam third in his class of 174, but after his education ended he never went on to work as a lawyer, instead focusing on doing business. U Phar died at the age of 51, when Aung San was in 8th grade.[58]

Aung San's paternal grandmother was Daw Thu Sa,[2] whose family traced their lineage from the royal family of the Pagan Kingdom through its last king, Narathihapate. Daw Thu Sa had several cousins who had worked within the government of the last Burmese kingdom. One of her cousins, Bo Min Yaung, had been the royal treasurer during the reign of King Mindon. King Mindon awarded Bo Min Yaung the title of "Mahar Min Kyaw Min Htin", an honorary title similar to knighthood given to those who are not close relatives of the Burmese royal family. He had a reputation for having a gentle and soft personality.[59]

Bo Min Yaung had a younger brother of the same name who had a great impact on Aung San's patriotic outlook.[60] The younger Bo Min Yaung was remembered by Daw Thu Sa as being popular in his hometown for his handsomeness, strength, writing ability, and swordsmanship, which he practiced every day. King Mindon employed him in diplomatic service, and by the reign of Burma's last king, Thibaw, he had been appointed to administer the region of Myo Lu Lin, close to the northern side of the Pegu Mountain Range in Upper Burma. After learning of King Thibaw's abdication and subsequent exile to the British Raj, following the brief Third Anglo-Burmese War in 1885, Bo Min Yaung became angry, and made up his mind to resist the British.[61] The rebellion failed. After his refusal to surrender, he was captured and executed by the British.[62]

Some sources have reported Bo Min Yaung's relationship to Aung San differently, claiming that he was Aung San's paternal grandfather, rather than his paternal grandmother's cousin.[63]

Legacy

[edit]

For his work towards Burmese independence and uniting the country, Aung San is revered as the architect of modern Burma and a national hero.

A Martyrs' Mausoleum was built at the foot of the Shwedagon Pagoda in 1947, and 19 July was designated Martyrs' Day, a public holiday.[64][65] Aung San's original mausoleum was destroyed by the blast on 9 October 1983 when the President of South Korea, Chun Doo-hwan was nearly assassinated by North Korean agents.[66][67] Another monument was built in its place.[68] Within months of Aung San's assassination, on 4 January 1948, Burma was granted independence. By August 1948, a civil war began between the Burmese military and various insurgents, including communists and ethnic militias. The internal conflict within Myanmar continues to the present day.[69][70]

Aung San's name had been invoked by successive Burmese governments since independence, until the military regime in the 1990s tried to eradicate all traces of Aung San's memory. Nevertheless, several statues of him adorn the former capital Yangon and his portrait still has a place of pride in many homes and offices throughout the country. Scott Market, Yangon's most famous market, was renamed Bogyoke Market in his memory, and Commissioner Road was retitled Bogyoke Aung San Road after independence. These names have been retained. Many other towns and cities in Burma have thoroughfares and parks named after him.[71] In the decades following Aung San's assassination many people came to view him as a symbol of democratic reform; during the 8888 Uprising in 1988 against the military dictatorship, many protesters carried posters of Aung San as symbols of their movement.[72] Many people at the time saw Aung San as a symbol of what Burma could have been, but was not at the time: prosperous, democratic, and peaceful.[73]

In 1962 the Burmese military, led by Ne Win, overthrew the civilian government in a coup and instituted military rule. The Burmese military justified the legitimacy of their government partially by citing the legacy of Aung San in leading the country in WWII, when he was both a military and political leader.[74] Following his coup Ne Win used official statements and propaganda to promote the idea that, as the leader of the armed forces and a member of the Thirty Comrades, he was the sole legitimate successor of Aung San.[75]

Banknotes featuring Aung San were first produced in 1958, ten years after his assassination. The practice continued until the uprising in 1988, when the government replaced his picture with scenes of Burmese life, possibly in an attempt to decrease the popularity of his daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi. In 2017 the Myanmar parliament voted 286–107 in favor of reinstating Aung San's image. The new 1,000-kyat notes bearing Aung San's image were produced and released to the public on 4 January 2020, a date chosen to mark the 72nd anniversary of Independence Day.[76]

Family

[edit]

While he was War Minister in 1942, Aung San met and married Khin Kyi, and around the same time her sister met and married Thakin Than Tun, the Communist leader. Aung San and Khin Kyi had four children.

After Aung San's assassination his widow was appointed Burma's ambassador to India, and the family moved abroad.[77]

Aung San's youngest surviving child, Aung San Suu Kyi, was only two years old when Aung San was assassinated.[78] She is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, served as State Counsellor of Myanmar, was the first female Myanmar Minister of Foreign Affairs, and is the leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD) political party. Aung San's oldest son, Aung San Oo, is an engineer working in the United States who has disagreed with his sister's political activities. Aung San's second son, Aung San Lin, died at age eight, when he drowned in an ornamental lake in the grounds of the family's house.[citation needed]

Aung San's youngest daughter, Aung San Chit, born in September 1946, died on 26 September 1946, the same day Aung San got into Governor's Executive council, a few days after her birth.[79] Aung San's wife Daw Khin Kyi died on 27 December 1988.

Names of Aung San

[edit]- Name at birth: Htein Lin (ထိန်လင်း)

- As student leader and a thakin: Aung San (သခင်အောင်ဆန်း)

- Nom de guerre: Bo Teza (ဗိုလ်တေဇ)

- Japanese name: Omoda Monji (面田紋次)

- Resistance period code name: Myo Aung (မျိုးအောင်), U Naung Cho (ဦးနောင်ချို)

- Contact code name with General Ne Win: Ko Set Pe (ကိုဆက်ဖေ)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Thant 213

- ^ a b Nay 99

- ^ Nay 106

- ^ Thant 214

- ^ Maung Maung 22–23

- ^ Smith 90

- ^ a b c d e f Aung San Suu Kyi (1984). Aung San of Burma. Edinburgh: Kiscadale 1991. pp. 1, 10, 14, 17, 20, 22, 26, 27, 41, 44.

- ^ Smith 54

- ^ Naw 28–37

- ^ Naw 36–38

- ^ Naw 41–43

- ^ Naw 44

- ^ a b c d Smith 58

- ^ Smith 56–57

- ^ Naw 45–48

- ^ Lintner 1990

- ^ Thant 217

- ^ Naw 49

- ^ a b c d Lintner 2003 41

- ^ a b c d Thant 228

- ^ Smith 57–58

- ^ Thant 219

- ^ a b Thant 229

- ^ a b c Smith 59

- ^ Houtman

- ^ Lintner 2003 42

- ^ a b c d Thant 252

- ^ Thant 230

- ^ Thant 252–253

- ^ Smith 60

- ^ Thant 238–240

- ^ Lintner 2003 73

- ^ Smith 65

- ^ Thant 240–241

- ^ Smith 65–66

- ^ Thant 244–245

- ^ Smith 66

- ^ Smith 73

- ^ Smith 69

- ^ a b Lintner 2003 80

- ^ Smith 77–78

- ^ Smith 78

- ^ a b c Thant 253

- ^ Smith 79

- ^ "The Panglong Agreement, 1947". Online Burma/Myanmar Library. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ^ South 26

- ^ Appleton, G. (1947). "Burma Two Years After Liberation". International Affairs. 23 (4). Blackwell Publishing: 510–521. doi:10.2307/3016561. JSTOR 3016561.

- ^ a b c d e Thant 254

- ^ Thant 248

- ^ a b Lintner 2003 xii

- ^ a b "Who Killed Aung San?". The Irrawaddy. 17 July 2017. Archived from the original on 30 March 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Lintner 2003 xii–xiii

- ^ Lintner 2003 xiii

- ^ Smith 71–72

- ^ The Irrawaddy 2

- ^ Thant 270–271

- ^ Kyaw Zwa Moe

- ^ Nay 99, 106

- ^ Nay 100–102

- ^ Nay 100

- ^ Nay 102

- ^ Nay 104

- ^ Aung

- ^ Ye Mon and Myat Nyein Aye

- ^ BBC News

- ^ "Materials on massacre of Korean officials in Rangoon", Korea & World Affairs, 7 (4), Historical Abstracts, EBSCOhost: 735, Winter 1983.

- ^ "Rangoon Bomb Shatters Korean Cabinet", Multinational monitor, vol. 4, no. 11, November 1983, archived from the original on 22 September 2017, retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Thant 293

- ^ Thant 258–259

- ^ Lintner 2003 203

- ^ Smith 6

- ^ Thant 33

- ^ Lintner 2003 342

- ^ Smith 198–199

- ^ "From The Archive | Rewards of Independence Remain Elusive". The Irrawaddy. 3 January 2018. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Zaw

- ^ Rogers 27

- ^ Thant 333

- ^ Wintle, Justin (2007). Perfect hostage: a life of Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma's prisoner of conscience. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-60239-266-3.

Sources

[edit]- Houtman, Gustaaf. "Aung San's Lan-Zin, the Blue Print and the Japanese Occupation of Burma". In Kei Nemoto (ed). Reconsidering the Japanese military occupation in Burma (1942–45). Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA). 30 May 2007. pp. 179–227. ISBN 978-4-87297-9640, Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- Lintner, Bertil. Burma in Revolt: Opium and Insurgency Since 1948. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books. 2003.

- Lintner, Bertil. The Rise and Fall of the Communist Party of Burma. Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publication. 1990

- Maung Maung. Aung San of Burma. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff for Yale University. 1962.

- Nay Eain. The Political Leaders Whose Names Will Live Forever. Yangon: Myo Myanmar. 2014. (in Burmese)

- "North Korea's History of Foreign Assassinations and Kidnappings" Archived 22 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 14 February 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- Rogers, Benedict. Burma: A Nation at a Crossroads. Great Britain: Random House. 2012.

- Smith, Martin. Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. 1991.

- South, Ashley. Ethnic Politics in Burma: States of Conflict. New York: Routelage. 2009.

- Stewart, Whitney. Aung San Suu Kyi: Fearless Voice of Burma. Twenty-First Century Books. 1997. ISBN 978-0-8225-4931-4

- Thant Myint-U. The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma. London: Faber and Faber Limited. 2008.

- Ye Mon and Myat Nyein Aye. "Martyr's Mausoleum Gets and Upgrade" Archived 18 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Myanmar Times. 17 June 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Zaw Zaw Htwe. "Gen. Aung San Returns to Myanmar Banknotes After 30-Year Absence" Archived 8 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine. The Irrawaddy. 7 January 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

External links

[edit]- Aung San's resolution to the Constituent Assembly regarding the Burmese Constitution, 16 June 1947.

- Kin Oung. Eliminate the Elite – Assassination of Burma's General Aung San & his six cabinet colleagues. Uni of NSW Press. Special edition – Australia 2011

- Burmese revolutionaries

- Burmese generals

- Aung San Suu Kyi

- Assassinated Burmese politicians

- Burmese collaborators with Imperial Japan

- Deaths by firearm in Myanmar

- 1915 births

- 1947 deaths

- People murdered in Myanmar

- University of Yangon alumni

- Communist Party of Burma politicians

- Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League politicians

- Government ministers of Myanmar

- Defence ministers of Myanmar

- State of Burma

- People from Magway Division

- People from British Burma

- Family of Aung San

- Politicians assassinated in the 1940s

- Burmese people of World War II