Habib Bourguiba

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as article suffers frequent nonsense grammar and may suffer political bias as alleged on Talk page. (July 2018) |

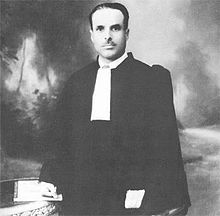

Habib Bourguiba Supreme Combatant | |

|---|---|

الحبيب بورقيبة | |

Bourguiba, 1960s | |

| 1st President of Tunisia | |

| In office 25 July 1957 – 7 November 1987 Interim to 8 November 1959 | |

| Prime Minister | Bahi Ladgham Hédi Nouira Mohammed Mzali Rachid Sfar Zine El Abidine Ben Ali |

| Preceded by | Office created (Muhammad VIII as King of Tunisia) |

| Succeeded by | Zine El Abidine Ben Ali |

| Prime Minister of Tunisia | |

| In office 11 April 1956 – 25 July 1957 | |

| Monarchs | King Muhammad VIII |

| Preceded by | Tahar Ben Ammar |

| Succeeded by | Bahi Ladgham (Indirectly) |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 15 April 1956 – 29 July 1957 | |

| Monarchs | King Muhammad VIII |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Sadok Mokaddem |

| Minister of Defense | |

| In office 15 April 1956 – 29 July 1957 | |

| Monarchs | King Muhammad VIII |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Bahi Ladgham |

| Speaker of the National Constituent Assembly | |

| In office 9 April 1956 – 15 April 1956 | |

| Monarchs | King Muhammad VIII |

| Preceded by | First officeholder |

| Succeeded by | Jallouli Fares |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Habib Ben Ali Bourguiba 3 August 1903[a] Monastir, French Tunisia |

| Died | 6 April 2000 (aged 96) Monastir, Tunisia |

| Resting place | Bourguiba mausoleum Monastir, Tunisia |

| Citizenship | Tunisian |

| Political party | Socialist Destourian Party (1964–1987) |

| Other political affiliations | Neo Destour (1934–64) Destour (1930–34) |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Jean Habib Bourguiba Hajer Bourguiba (adoptive) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | M'hamed Bourguiba (brother) Mahmoud Bourguiba (brother) Saïda Sassi (niece) |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Occupation | Political activist |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

| Website | www |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political career

|

||

Habib Bourguiba (/bʊərˈɡiːbə/ ⓘ boor-GHEE-bə; Tunisian Arabic: الحبيب بورقيبة, romanized: il-Ḥbīb Būrgībah; Standard Arabic: الحبيب أبو رقيبة, romanized: al-Ḥabīb Abū Ruqaybah; 3 August 1903[a] – 6 April 2000) was a Tunisian lawyer, nationalist leader and statesman who led the country from 1956 to 1957 as the prime minister of the Kingdom of Tunisia (1956–1957) then as the first president of Tunisia (1957–1987). Prior to his presidency, he led the nation to independence from France, ending the 75-year-old protectorate and earning the title of "Supreme Combatant".

Born in Monastir to a poor family, he attended Sadiki College and Lycée Carnot in Tunis before obtaining his baccalaureate in 1924. He graduated from the University of Paris and the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po) in 1927 and returned to Tunis to practice law. In the early 1930s, he became involved in anti-colonial and Tunisian national politics, joining the Destour party and co-founding the Neo Destour in 1934. He became a key figure of the independence movement and was repeatedly arrested by the colonial administration. His involvement in the riots of 9 April 1938 resulted in his exile to Marseille during World War II.

In 1945, following Bourguiba's release, he moved to Cairo, Egypt to seek the support of the Arab League. He returned to Tunisia in 1949 and rose to prominence as the leader of the national movement. Although initially committed to peaceful negotiations with the French government, he had an effective role in the armed unrest that started in 1952 when they proved to be unsuccessful. He was arrested and imprisoned on La Galite Island for two years, before being exiled in France. There, he led negotiations with Prime Minister Pierre Mendès France and obtained internal autonomy agreements in exchange for the end of the unrest. Bourguiba returned victorious to Tunis on 1 June 1955, but was challenged by Salah Ben Youssef for the party leader position. Ben Youssef and his supporters disagreed with Bourguiba's "soft" policies and demanded full independence of the Maghreb. This resulted in a civil war that pitted Bourguibists, who favored a gradual policy and modernism, against Youssefists, the conservative Arab nationalist supporters of Ben Youssef. The conflict ended in favor of Bourguiba with the Sfax Congress of 1955.

Following the country's independence in 1956, Bourguiba was appointed prime minister by king Muhammad VIII al-Amin and acted as de facto ruler before proclaiming the Republic on 25 July 1957. He was elected interim President of Tunisia by Parliament until the ratification of the Constitution. During his rule, he implemented a strong education system, worked on developing the economy, supported gender equality, and proclaimed a neutral foreign policy, making him an exception among Arab leaders. The main reform that was passed was the Code of Personal Status which implemented a modern society.[clarification needed] He established a strong presidential system which turned into a twenty-year one-party state dominated by his own party, the Socialist Destourian Party. A cult of personality also developed around him, before he proclaimed himself president for life in 1975, during his fourth 5-year term.

The end of his 30-year rule was marked by his declining health, a war of succession, and the rise of clientelism and Islamism. On 7 November 1987, he was removed from power by his prime minister, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, and kept under house arrest in a residence in Monastir. He remained there until his death and was buried in a mausoleum he had previously built.

1903–1930: Early life

[edit]Childhood years

[edit]Bourguiba was born in Monastir, the eighth child and final son of Ali Bourguiba and Fatouma Khefacha. Bourguiba's official birthdate is 3 August 1903, though he stated he was likely born a year earlier, on 3 August 1902, or possibly 1901. Bourguiba's mother gave birth to him when she was 40, which, according to Bourguiba, was a source of great shame for her. His father, who was 53 years old, wondered whether he could raise him properly. Despite financial hardship, Ali Bourguiba gave great importance to the education of his children. He was enrolled in the army by general Ahmed Zarrouk, and spent nineteen years of his life campaigning before retiring. Eager to avoid such a fate for his last child, he decided to ensure Habib obtained his Certificat d'études primaires, which would dispense him from military service, just like his elder sons. Around the time Bourguiba was born, his father became councilman, and was, therefore, part of the notables of the city. This allowed him to improve both his financial and social situation and permitted him to provide a modern education future for his last son, just like his brother.[1]

Habib Bourguiba grew up among women, as his brother was in Tunis and his father was elderly. He spent his days with his mother, grandmother and sister, Aïcha and Nejia, which permitted him to notice the casual household chores of women and their inequality with men.[2] After starting his elementary education in Monastir, his father sent him to Tunis in September 1907, when he was 5, to pursue his studies at the Sadiki primary school. The young boy was profoundly affected by the separation from his mother at that early age.[3] At the time of his arrival, the city was struggling against the protectorate, an early phase of the Tunisian national movement led by Ali Bach Hamba. Meanwhile, Habib settled in the wealthy neighbourhood of Tourbet el Bey in the medina of Tunis, where his brother, M'hamed, rented a lodging on Korchani Street. As the school year began, his brother enrolled him in Sadiki College where the superintendent described him as "turbulent but studious".[4]

The young Habib spent his vacations in Monastir, aiding others with chores. At the end of the holiday season, he returned to Tunis where, after classes, he used to wander around in the streets. On Thursdays, he watched the bey chair the weekly seals ceremony. The Jellaz demonstrations of 1911 and the resulting execution of Manoubi Djarjar that followed influenced his nascent political opinions.[5] Bourguiba earned his certificat d'études primaires in 1913, which greatly satisfied his father.[6] Bourguiba avoided military service, and, like his elders, was admitted as an internal in Sadiki College to pursue his secondary studies freely. His mother died in November 1913, when he was 10 years old.[7]

Teenage years and secondary studies

[edit]When World War I started in September 1914, Bourguiba moved out from his brother's house and settled in the dormitories of Sadiki College. Budgetary restrictions, enacted in order to support the war effort, contributed to malnutrition and inadequate supplies. These circumstances led students to protest, and Bourguiba soon came to participate.[8] He admired Habib Jaouahdou, a student who told others about national struggles beyond the walls of high school. Jaouahdou proposed that they welcome Abdelaziz Thâalbi when he returned from exile, Bourguiba being part of the welcoming Sadiki delegation.[9] In addition, the funerals of nationalist leader Bechir Sfar in Jellaz had also impacted him, as he travelled with his father. At school, one of his professors taught him the art of French writing and, indirectly, Arab literature. Despite that, his grades were low; Bourguiba did not pass his Arabic patent in 1917, which would have allowed him to get an administrative function.[10] The headmaster permitted him to restart his sixth and final year of high school, in 1919–20. But the winter season and aforementioned malnutrition severely worsened his health, and he was hospitalized following his primary infection. Accordingly, he was obliged to abandon his studies and remain at the hospital.[11]

In order to heal, Bourguiba spent nearly two years living with older brother Mohamed, medic at the local hospital of Kef who also happened to be a strong modernist and advocating secularism. Mohamed lived with an Italian nurse who welcomed young Habib properly and had an important part in his improvement, by "filling in his emotional void", according to Souhayr Belhassen and Sophie Bessis. His journey in there, which lasted 21 months from January 1920, was a major turning point in his life. The inhabitants of the city helped him integrate: He learned how to play cards, discussed military strategies, got interested in Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and also visited his other brother, Ahmed, in Thala where he learned horse riding. He also participated in theatrical activities. Bourguiba rehearsed with his brother, who had a passion for theater and performed on stage.[12] The foundation of the Destour party while he was in Kef, increased Bourguiba's interest in Tunisian nationalism. He expressed his will to pursue his secondary studies and thus, study law in France, so he could struggle against the colonial power. The family council that was held to discuss this matter was a complete failure, his brothers considering him as "unsuccessful" and were not ready to finance his studies. Only his thirty years old single brother, Mahmoud, promised to aid him. With his support, Bourguiba was enrolled in Lycée Carnot of Tunis, in classe de seconde, because he was too weak to study in classe de première.[13]

In high school, Bourguiba achieved high grades in Mathematics with the help of the new teacher that taught him. He obtained excellent results and ended up choosing Philosophy section, after passing the first part of baccalaureate. He also became friends with Tahar Sfar and Bahri Guiga. The group was called the "Sahelian Trio". He often went to libraries and showed interest in history even though, sometimes, he skipped classes, mainly on Friday afternoons, to attend Habiba Msika's performance of L'Aiglon. He was soon affected by the inequalities between French and Tunisians.[13] In 1922, when Naceur Bey threatened to abdicate because of resident-general Lucien Saint's maneuvers, public opinion decided to mobilize for this nationalist bey. On 22 April 1922, Bourguiba was part of the protesters to support the monarch. Influenced by that event, he used to participate in debates with his friends and got interested in political and philosophical learning, supporting socialism.[14] In 1923–24, his final year was fundamental as he had a tight contest with another French classmate, in order to obtain a scholarship to study in Paris. He also benefited from the support of his brother Mahmoud, who promised to send him 50 francs per month. In 1924, he sat for his baccalaureate and obtained outstanding marks with honours. At the end of exams, Bourguiba embarked on an old boat, Le Oujda, in order to pursue his studies in France and discover the colonial power.[15]

Higher education in Paris

[edit]When he arrived in Paris, Bourguiba settled in Saint-Séverin hotel, near Place Saint-Michel, where he occupied a room located on the sixth floor for 150 francs per month. Having had some hard times, his problems were resolved as he obtained a scholarship of 1800 francs, payable in two installments, and enrolled in Paris law School, in the Sorbonne to attend psychology and literature classes.[16][17] Aware that he came to France to "arm himself intellectually against France", he devoted himself to law and to the discovery of French civilization. Bourguiba often participated in political debates, read newspapers and followed closely the evolution of French politics during the Third Republic. Sensitive to the ideas of Leon Blum, following the Congress of Tours, he was opposed to the Bolsheviks and got interested in Mahatma Gandhi's process to transform the Indian national Congress into a powerful mass organization. In addition, he showed a great interest in his fellow Tunisian, Mahmoud El Materi.[18]

After vacations spent between Mahdia and Monastir, Bourguiba returned to Paris for the start of the 1925–26 school year, worried about the nationalist struggle in his country. His conditions improved as he moved in the University Campus in Jourdan boulevard, where he lodged in room number 114. The sponsor, Taïeb Radhouane, sent him through the association Les Amis de l'étudiant, the registration fees to register for Paris Institute of Political Studies, where he started to attend public finance classes. He also obtained a financial aid from his friend and protector, Mounier-Pillet, who was his former teacher in Monastir. The same year, his friends Sfar and Guiga, joined him while he was tutoring a young Sfaxian boy, Mohamed Aloulou, sent by his parents to sit for the baccalaureate exam in Lycée Louis-le-Grand.[19] One day in 1925, while tidying his room, Bourguiba found the address of a woman his protector recommended him to meet: Mathilde Lefras, a 35 years old widow whose husband died during the war. He met her for the first time in her apartment, on the first floor of a building in the 20th arrondissement of Paris. She invited him to enter and asked him to tell his story. Touched by his background, she asked to see him once again, and, in the upcoming months, invited him to move in with her. Since then, he gave away his room in the campus and settled with Mathilde.[20] With this new way of life, Bourguiba distanced himself from the other students but also the Tunisian struggle, as a strong repression started back at the country.[21]

During the summer of 1926, Bourguiba returned to Monastir but did not show any interest in political issues in his country. His father died in September and he received a telegram from Mathilde, announcing that she was pregnant. This situation and the parenting responsibility that lay ahead, worried him. Thus, he decided to raise the child, despite his friend's advice to abandon the baby and break up with Mathilde. This pregnancy reassured him as he thought he was sterile. But the relationship of the couple worsened to a point that Bourguiba left the house to sleep at his friends' place, back at the campus.[22] On 9 April 1927, Mathilde gave birth to a boy, whom they named Jean Habib. They moved into another apartment in Bagneux, in the Parisian suburbs. Bourguiba, sick at the time, had to prepare for his final exams, which he sat for a month after the birth of his son.[23] He obtained respectively a bachelor's degree in law and the higher degree of political studies from the Paris Institute of Political Studies.

Early adult life and professional career

[edit]In August 1927, Bourguiba who was 26 at the time, returned to Tunisia, with his girlfriend, his son, Habib Jr. but also a deep knowledge of French politics during the Third Republic. His journey in France had influenced his thinking with the liberal values of the social-radical secular country, shared earlier by his brother Mohamed. Following his return to Tunisia, he married Mathilde, with Mahmoud Laribi as his best man, and settled in Tunis. At the time, he was not interested in politics but in his professional career, every debuting lawyer having to do a three-year traineeship under the supervision of another experienced lawyer.[24] From October 1927 to October 1928, he worked for Mr. Cirier, who dismissed him after six weeks, then for Mr. Pietra and Scemama, who did not pay him for two months and charged him with writing responsibilities. Bourguiba then resigned to work for Mr. Salah Farhat, chairman of the Destour party, until Mr. Sebault hired him for 600 francs per month, which led Bourguiba to work for him for an additional year to the three mandatory ones.[25]

In the context of colonial oppression, Bourguiba felt the effects of inequality. He spent the next year unemployed. This inequality led him to discuss these matters with both Tunisian and French friends, who agreed with the necessity to start a reform process aiming to get Tunisia to resemble France, that was, liberal, modern and secular.[26] On 8 January 1929, while replacing his brother who could not attend a conference held by Habiba Menchari, an unveiled woman who advocated gender equality, Bourguiba defended Tunisian identity, culture and religion by opposing Menchari's position to rid women of their veils. Bourguiba responded saying that Tunisia was threatened by the forfeiture of its personality and that it had to be preserved until the country was emancipated. This statement surprised liberals like the French unionist Joachim Durel. The controversy that followed opposed him to Bourguiba for nearly a month, Bourguiba writing in L'Étendard tunisien while Durel responded in Tunis socialiste.[26]

The year 1930 was the peak of French colonization in North Africa, which led France to celebrate the centenary of the French conquest of Algeria, by organizing a eucharistic congress in Tunisia. On this occasion, millions of Europeans invaded the capital city and went to the Saint-Lucien de Carthage Cathedral disguised as crusaders which humiliated and revolted the people who protested against what they considered a violation of an Islamic land by Christians. The protesters, strongly repressed, were brought to justice. Some of them had Bourguiba as their lawyer, since he had not participated in the event. He also remained neutral when Tahar Haddad was dismissed from his notary duties.[27] He estimated at that moment, that the main goals were political, while other problems of society were secondary. He insisted that Tunisian identity had to be affirmed, declaring: "Let us be what we are before becoming what we will".[28]

1930–1934: Early political career

[edit]In the beginning of the 1930s, Habib Bourguiba, feeling the effects of colonial inequalities, decided to join the main political party of the Tunisian national movement, the Destour, alongside his brother M'hamed and his mates Bahri Guiga, Tahar Sfar and Mahmoud El Materi.[29] Revolted by the festivities of the 30th eucharistic congress, held from 7 to 11 May 1930 in Carthage, and which he considered as a "violation of islamic lands", the young nationalists found it necessary to get involved. With the upcoming preparations for the 50th anniversary celebration of the protectorate and the scheduled visit of French president Paul Doumer, the young nationalists decided to act. Bourguiba denounced the rejoicing, in the newspaper Le Croissant, ran by his cousin Abdelaziz El Aroui, as a "humiliating affront to the dignity of the Tunisian people to whom he recalls the loss of freedom and independence". Therefore, the leaders of the Destour party gathered in emergency at Orient Hotel, in February 1931, where it was decided to found an endorsing committee to the newspaper of Chedly Khairallah, La Voix du Tunisien, which switched from weekly to daily and had among its editors the young nationalist team.[30]

Bourguiba multiplied his denunciations of the attempts aiming the Tunisian personality but also the beylical decree system and Europeans' advantages in his numerous articles in L'Étendard tunisien and La Voix du Tunisien, claiming Tunisian access to all administrative positions.[31] Soon, he described his own definition of the protectorate, challenging its existence, not just its effects like the elder nationalists did, by writing on 23 February 1931 that "for a healthy strong nation that international competitions and a momentary crisis forced into accepting the tutelage of a stronger state, the contact of a more advanced civilization determines in it a salutary reaction. A true regeneration occurs in it and, through judicious assimilation of the principles and methods of this civilization, it inevitably come to realize in stages its final emancipation".[32]

Thanks to the originality with which Bourguiba, Sfar, Guiga and El Materi addressed the problems, La Voix du Tunisien became a very popular newspaper. Their new reasoning attracted not only the interest of public opinion but also that of French preponderants, powerful businesspersons and great land owners, who had a strong influence on the colonial administration.[33] Opposed to the daring work of the young team, they achieved the censorship of all nationalist papers through the Residence (the colonial government) on 12 May 1931. A few days later, Habib and M'hamed Bourguiba, Bahri Guiga, Salah Farhat and El Materi were all prosecuted.[33] However, they succeeded in obtaining the adjournment of their trial until 9 June 1931.[30] On that day, numerous people came to show their support to the charged team getting their trial to be postponed once again. In response to this decision, Resident-general François Manceron, eager to put an end to the nationalist issue, achieved to outwit discord between Khairallah, the owner of the paper and the young nationalists. A conflict occurred between both parties about the management of La Voix du Tunisien which led to the team eager to take charge of the paper. However, because of the refusal of Khairallah, they decided to resign from the daily paper.[34]

Despite the split-up, the two Bourguibas, El Materi, Guiga and Bahri kept in touch and decided to found their own paper thanks to the aid of pharmacist Ali Bouhajeb.[35] Therefore, on 1 November 1932, was published the first edition of L'Action Tunisienne which had as redactional committee the young team joined by Bouhageb and Béchir M'hedhbi. Thus, Bourguiba devoted his first article to budget.[36] Soon disappointed by the resigned moderation of their elders, the young nationalists unleashed and took the defence of the lower classes. Bourguiba, who saw his popularity increase thanks to his writings, frequented often intellectual circles whom he had just met.[37] He showed both clarity and accuracy in his writings, which revealed a talented polemicist, thanks to his strong legal expertise. Furthermore, he had worked on demonstrating the colonial exploitation mechanism by ascending from effects to causes, while showing a great interest in social phenomenons, inviting the workers and students to organize and thus, defend themselves better against exploitation. In addition, he encouraged the defense and safeguard of the Tunisian personality.[38]

With the economic crisis deepening and the resigned moderation of the nationalists, Bourguiba and his fellow mates reckoned that a good cause would be necessary enough to rebuild the nationalist movement on new basis by choosing new methods of action. In February 1933, when M'hamed Chenik, banker and chairman of the Tunisian credit union, got into trouble with the Residence, Bourguiba is the only one to defend him.,[39] reckoning that this issue could permit him to rally the bourgeois class, considered as collaborator with France, and unify the country around nationalism.[40] Nevertheless, it only ended up with the resignation of Guiga, M'hedhi and Bouhajeb. Thus, Bourguiba abandoned his lawyer work to concentrate on running the journal by his own.[41] But the occasion to express himself soon turned up: The Tunisian naturalization issue, which was a popular case among the nationalists during the 1920s reappeared, in the start of 1933, with protests in Bizerte against the burial of a naturalized in a Muslim cemetery.[42] Bourguiba decided to react and unleash a campaign to support the protests in L'Action Tunisienne which will soon be reprised by numerous nationalist newspapers, denouncing an attempt to Frenchify the "whole Tunisian people".[43]

The firm stance of Bourguiba led him to acquire a strong popularity among the nationalist circles. Furthermore, the congress held by the Destour which took place on 12 and 13 May 1933 in Tunis, ended in favor of the young team of L'Action tunisienne, elected unanimously in the executive party committee.[44] This strong position among the movement permitted them to influence party decision, eager to unify all the factions among a nationalist front. In the meantime, due to the ongoing naturalist issue in Tunis, the Residence decided the suspension of every nationalist paper on 31 May, including L'Action Tunisienne but also the prohibition of Destour activity. However, the French government convinced that Manceron had acted tardily in taking expected measures, replaced him by Marcel Peyrouton on 29 July 1933. Bourguiba deprived of his freedom of speech in this repression atmosphere and trapped inside the Destour moderate policy, aspired to get his autonomy back.[45]

On 8 August, the occasion to express his views arrived when incidents began in Monastir following the burial of a naturalized child by force in a Muslim graveyard. Soon, law enforcement and population started a fight, which led Bourguiba to convince certain Monastirians to choose him as their lawyer. Furthermore, he led them to protest to the bey, on 4 September. The party leadership seeing this as an occasion to get rid of a new form of activism they dislike, decided to reprimand the young nationalist.[46] Bourguiba, who considered the Destour and its leaders as an obstacle to his ambitions, decided to resign from the party on 9 September. Soon enough, he had learned from this experience. This success obtained by popular violent uprising showed the failure of the Destour's methods, consisting mainly of petitions. Only violence of determined groups could lead the Residence to step back and negotiate the solutions; this was his course of action until 1956.[47]

1934–1939: Rising nationalist leader

[edit]Founding of Neo-Destour and colonial repression

[edit]

After he resigned from the executive committee of Destour, Bourguiba was on his own once again. However, his fellow mates of L'Action Tunisienne soon were in conflict with the elders of the party, ending with the exclusion of Guiga, on 17 November 1933 and the resignation of El Materi, M'hamed Bourguiba and Sfar from the executive committee on 7 December 1933.[48] Soon referred to as "rebels", they were joined by Bourguiba and decided to undertake a campaign all over the country and explain their political positions to the people. Meanwhile, the elders of the Destour unleashed a propaganda campaign aiming to discredit them. Therefore, the young team visited areas severely affected by the economic crisis, including Ksar Hellal and Moknine where they were reluctantly welcomed. Thanks to Ahmed Ayed, a wealthy and respected Ksar Hellal inhabitant, the occasion to explain themselves was given. On 3 January 1934, they gathered with a part of the Ksar Hellal population in his house to clarify the reasons of their conflict with the Destour and specify their conception of national struggle for emancipation.[49]

The speeches and determination to act of this new generation of nationalist was greatly welcomed by the Tunisian population which did not hesitate to criticize the "neglect of the Destour leadership to defend their interests".[50] Upon the refusal of the executive committee to organize a special congress aiming to change their political orientations and thanks to the support of the population and notables, the "secessionists" decided to hold their own congress in Ksar Hellal on 2 March 1934.[51] During the event, Bourguiba called the representatives to "choose the men who shall defend in their name the liberation of the country". The congress ended with the founding of a new political party, the Neo-Destour, presided by El Materi, and Bourguiba was designated chairman.[52]

After the party was founded, the Neo-Destour aimed to strengthen its position among the political movements. The young team faced the resident-general, Marcel Peyrouton, who was dedicated to stopping the nationalist protests in an economic crisis atmosphere, which was an opportunity to seduce a larger audience. Thus, they needed to earn a greater place on the political stage, spread their ideology and rally the supporters of a still-strong Destour, and also convince the lower classes that the Neo-Destour was their advocate. The Neo-Destour invited the lower classes to join in "a dignity tormented by half a century of protectorate".[53] Therefore, Bourguiba traveled all around the country and used new methods of communication different from that of the Destour elders. The lower classes, alienated and troubled by economic crisis, were convinced by his speech and joined his cause, bringing their full support to it. Units were created all over the country and a new structure was settled, making the Neo-Destour a more efficient movement than all those before. If the elders addressed the colonial oppressor to express their requests, the "secessionists" addressed the people.[53] Even worldwide, the new party succeeded in finding support among French socialists, including philosopher and politician Félicien Challaye, who endorsed the Neo-Destour.[54]

However, in Tunisia, the Neo-Destour had to face the strong opposition of resident-general Peyrouton who, firstly, endorsed the initiative of the "secessionists", eyeing it as a mean to weaken the nationalist movement, but soon withdrew his support because of the new successful methods adopted by the young team and their unexpected requests. Indeed, Bourguiba and his fellows from the newly created-party soon showed "more dangerous" demands by asking for national sovereignty and the ascending of an independent Tunisia "accompanied by a treaty guaranteeing France a preponderance both in the political as well as in the economic field compared to other foreign countries", in an article published in L'Action Tunisienne.[55]

All these demands led to a conflict between the French government and the Tunisian nationalist movement.[56] In addition, the party leadership secured the population to be sensitive to their message, thanks to their tours along the country.[57] These tensions led the residence to answer the nationalist requests by serious measures of intimidation.[58] The repression unleashed is furthermore violent: Peyrouton forbade all the newspapers still publishing including Tunis socialiste but also L'Humanité and Le Populaire, on 1 September 1934. On 3 September, the colonial government ordered raids against all nationalist leaders in the country, including both Destours and the Tunisian Communist Party.[32] Bourguiba was arrested and then sent to Kebili, in the south, under military supervision.[33] Meanwhile, the arrests of the mean leaders generated discontent among the population. While Guiga and Sfar tried to pacify them in order to negotiate the release of the imprisoned, Bourguiba and Salah Ben Youssef were for the retention of the unrest.[59] Furthermore, riots occurred along the country, leading the residence to reinforce the repression.[60] Soon, the South gathered a major part of Tunisian political leaders: The two Bourguibas in Tataouine, El Materi in Ben Gardane, Guiga in Médenine and Sfar in Zarzis.[61]

On 3 April 1935, all the deported were transferred to Bordj le Boeuf.[62] Although glad to be all together, they were soon in conflict upon the strategy the party had to choose.[63] While the majority were part of the decay of the uprising and the dismissal of the methods adopted in 1934, Bourguiba was opposed to any concession.[64][49] Soon he was accused by his fellow detainees to "lead them to their loss";[64] Only Ben Youssef was not against Bourguiba's methods since 1934 but reckoned they needed to be free again at all cost and therefore, attempt to save what can still be. However, the conflict receded due to the hard conditions of detention aiming to coax them.[63]

From negotiation attempt to confrontation

[edit]

In the start of 1936, due to the ineffective policy of Peyrouton, the French government proceeded to his replacement with Armand Guillon, designated in March whose mission is to reinstate peace.[65] Therefore, he succeeded in putting an end to two years of colonial repression, promoting dialogue and freeing the nationalist detainees on 23 April. Thus, Bourguiba was sent to Djerba where he was visited by the newly settled resident-general who was ready to negotiate with him, aiming to put an end to the conflicts and pursue a new liberal and humane policy. On 22 May, Bourguiba was freed of all charges and had the permission to regain his home in Tunis, alongside his fellow detainees. Meanwhile, in France, the Popular Front ascended with the settlement of Leon Blum's cabinet in June.[66] This was a great opportunity for the leaders, who had always been close to the socialists. Soon, they met Guillon who promised to restore restricted liberties.[67] Very satisfied by their interview with Guillon, the leaders were convinced that the ascending of the Blum ministry and the arrival of Guillon as head of the colonial government would be the start of flourishing negotiations which would lead to independence, even though they did not state it publicly.[68]

On 10 June, the National Council of Neo-Destour gathered to establish a new policy towards this change in the French government. It ended with the endorsement of the new French policy and elaboration upon a series of feasible requests, to which the Neo-Destour expected a quick resolution. At the end of the meeting, Bourguiba was sent to Paris to set forth the platform of the party.[69] In France, he became close to such Tunisian nationalist students as Habib Thameur, Hédi Nouira and Slimane Ben Slimane.[70] Furthermore, he met under-secretary of state for foreign affairs, Pierre Viénot, on 6 July 1936.[71] This publicly stated interview was unpopular among the French colonialists in Tunisia, which led later meetings to be conducted secretly. But French authorities were opposed to the hopes of Tunisian militants, and some of them even thought that it was a mere illusion.[72] When he returned to Tunis, in September, the political atmosphere had changed with the re-establishment of liberties, which permitted the expansion of Neo-Destour and an increase in its members.[73]

The resident-general in Tunisia introduced assimilation reforms by the end of 1936. This statement is the start of uprisings by the beginning of 1937. Viénot, travelling to Tunisia, reacted by declaring that "certain private interests of the French of Tunisia do not necessarily confound with those of France".[72] Meanwhile, Bourguiba went to Paris, and then to Switzerland to attend a lecture about the capitulation held in April in Montreux. There, he met numerous Arab nationalist representatives including Chekib Arslan, Algerian Messali Hadj and Egyptian Nahas Pasha.[72]

In June, the resigning Blum Cabinet was replaced by the third Chautemps Cabinet, led by Camille Chautemps. Due to the procrastination of the new cabinet, the nationalists resumed to their fight and were active in making their requests a reality. Therefore, Bourguiba wished that Abdelaziz Thâalbi, founder of the Destour who had just returned from exile, endorsed the Neo-Destour to strengthen its positions. But his wish was not fulfilled for the elder leader had other prospects about the party, desiring to unify the old Destour with the new. Due to his refusal, Bourguiba decided to react by sabotaging Thaalbi's meetings.[74] In Mateur, the fight ended with numerous deaths and injured but Bourguiba succeeded in strengthening his positions and appearing as the unique leader of the nationalist movement, rejecting, once and for all Pan-Arabism and anti-occidentalism. The split up was, therefore, final between both parties. Fearing attacks, the Destourian party gave up public meetings, using newspapers to respond their opponents.

However, Bourguiba chose moderation regarding the relation with France. Meanwhile, within the party, two factions appeared: The first one, moderate, was led by El Materi, Guiga and Sfar, favoring dialogue while the second one, radical, was directed by the young members, including Nouira, Ben Slimane and Thameur, who were supporters of confrontation. At the time, Bourguiba was hesitant to choose between the two factions because he needed the support of the youth to gain domination upon the Neo-Destour, the leadership still being among the founding moderate members. Nevertheless, he soothed the tensions of the young, estimating that a confrontation with France would only have bad consequences and that the dialogue can still be favored.[75] In the start of October, he flew to Paris, aiming to pursue negotiations, but returned without any result. Thus, he realized there was nothing to be awaited from France.[75]

In this conjecture, was held the second congress of Neo-Destour in Tribunal Street, Tunis, on 29 October 1937. The voting of a motion regarding the relations with France was in the agenda. The congress represented the fight of the two factions which appeared within the last months. In his speech, Bourguiba tried to balance both trends. Upon reducing the influence of the Destour over the nationalist movement, he strongly defended the progressive emancipation policy which he had advocated:

Independence can happen only according to three formulas :

- A widespread, popular and violent revolution which will put an end to the protectorate ;

- A french military defeat during a war against another country ;

- A pacific stepwise solution, with the help of France and under its supervision.

The imbalance in the power forces between the people of Tunisia and those of France eliminates every chance for a popular victory. A French military defeat shall not bring independence because we shall fall under the claws of a new colonialism. Therefore, only the path of a peaceful liberation under the supervision of France, remains.[74]

The congress, which finished on 2 November, ended by withdrawing its support to the French government and therefore, the confidence the party had granted it for nearly two years. Bourguiba, who helped numerous young people join the leadership, strengthened his position and authority among the Neo-Destour and ended up victorious.[76]

While the party twitched and the newly restored repression had ended with seven death in Bizerte,[32] Bourguiba chose confrontation. On 8 April 1938, an organized demonstration happened peacefully but Bourguiba, convinced that violence was necessary, urged Materi to repeat the demonstrations by saying, "Since there was no blood, we need to repeat. There must be blood spilled for them to speak of us".[32] His wish was satisfied the following morning. The riots of 9 April 1938 ended with one dead policemen, 22 protestors and more than 150 injured.[77][78] The following day, Bourguiba and his mates were arrested and detained at the Civilian Prison of Tunis, where Bourguiba was interrogated. On 12 April, the Neo-Destour was dissolved, but its activism was pursued in secret.[32] On 10 June 1939, Bourguiba and his companions were charged with conspiracy against public order and state security and incitement of civil war. Therefore, he was transferred to the penitentiary of Téboursouk.

1939–1945: World War II

[edit]At the outbreak of World War II, Bourguiba was transferred on board of a destroyer, into the fort of Saint-Nicolas in Marseille on 26 May 1940.[32] There he shared his cell with Hédi Nouira. Convinced that the war would end with the victory of the Allies, he wrote a letter to Habib Thameur, on 10 August 1942, to define his positions:

Germany will not win the war and cannot win it. Between the Russian colossi but also the Anglo-Saxons, who hold the seas and whose industrial possibilities are endless, Germany will be crushed as if in the jaws of a irresistible vise [...] The order is given, to you and to the activists, to make contact with Gaulist French to combine our clandestine action [...] Our support must be unconditional. It is a matter of life and death for Tunisia.[74]

He was transferred to Lyon and imprisoned in Montluc prison on 18 November 1942 then in Fort de Vancia until Klaus Barbie decided to free him and take him to Chalon-sur-Saône. He was greatly welcomed in Rome, alongside Ben Youssef and Ben Slimane, in January 1943, upon the request of Benito Mussolini who hoped to use Bourguiba to weaken the French resistance in North Africa. The Italian minister for foreign affairs tried to obtain from him a declaration in their favor. At his return's eve, he accepted to deliver a message to the Tunisian people, via Radio Bari, warning them against all the trends. When he returned to Tunis, on 8 April 1943, he guaranteed that his 1942 message was transmitted to all the population and its activists. With his position, he stood out from the collaboration of certain activists with the German occupant, settled in Tunisia in November 1942 and escaped the fate of Moncef Bey, dethroned with the liberation, in May 1943, by general Alphonse Juin, accusing him of collaboration.[74] Bourguiba was freed by the Free French Force on 23 June.

In this period, he met Wassila Ben Ammar, his future second wife. Bourguiba, who was closely watched, did not feel like resuming the fight. Therefore, he requested the authorization to perform the pilgrimage of Mecca. This surprising request was refused by the French authorities. He then decided to flee in Egypt and in order to do that, crossed the Libyan borders, disguised in a caravan, on 23 March 1945 and arrived in Cairo in April.[32]

1945–1949: Journey in Middle East

[edit]Bourguiba settled in Cairo, Egypt where he was aided by his former monasterial teacher, Mounier-Pillet, who lived in the Egyptian Capital city.[79] There, Bourguiba met numerous personalities, such as Taha Hussein while participating in many events held in the city. He also met Syrians, who had just obtained their independence from France, and thus stated that "with the means they dispose, Arab countries should show solidarity with the national liberation struggles of the Maghreb". Even though his efforts were intensified, Bourguiba knew that nobody would support his cause as long as there was little tension between France and Tunisia. The Arab League was preoccupied mainly by the Palestinian issue, other requests not being their top priority. Therefore, he charged Ben Youssef to start these Franco-Tunisian tensions so that he could attract the attention of the Middle East.[80]

Bourguiba pursued his efforts. Furthermore, he met Abd al-Aziz ibn Saud and tried to sensitize him to support the Tunisian nationalist struggle, but in vain.[81] Due to the postponed promises of the people of Middle-East, Bourguiba decided to create an office of Neo-Destour in Cairo. Therefore, he invited Thameur, Rachid Driss, Taïeb Slim, Hédi Saïdi and Hassine Triki, detained by France and freed by Germans during the war, to join him in the Egyptian Capital. They arrived on 9 June 1946, aiding Bourguiba to start the rallying point of the North African community in Cairo.[82] Soon, they were joined by Algerian and Moroccan nationalists. Furthermore, Bourguiba's speech was famous among the Anglo-Saxon media, and Maghrebi nationalism became more efficient in Cairo.[81] Bourguiba was more and more convinced that the key to the nationalist struggle resided within the United States whose interests were same as those of the Maghrebi nationalists.[83] Thus, he was looking forward to go to the states and benefited from the support of Hooker Doolittle, American consul in Alexandria. Firstly, he went to Switzerland, then Belgium, and covertly passed the borders to get to Antwerp, abroad the Liberty ship, on 18 November.[83] On 2 December 1946, Bourguiba arrived in New York City while the session of the General Assembly of the United Nations opened.[84]

There, Bourguiba took part in numerous receptions and banquets which was for him an occasion to meet American politicians, such as Dean Acheson, under-secretary of State, whom he meets in January 1947.[85][86] Upon his trip to the United States, Bourguiba concluded that the superpower would support Tunisia in case its case was submitted to the United Nations. He based this idea on the United Nations Charter, signed by France and which stipulated the right of nation to self-determination. Therefore, he met Washington, D.C. officials and gained the attention of American public opinion thanks to the help of Lebanese Cecil Hourana, director of the Arab office of information in New York. Bourguiba, then, was strongly convinced he could bring up the Tunisian case in the international with the help of the five Arab states members of the United Nations.[85]

Meanwhile, in Cairo, the Arab League resigned to inscribe the North African case is its agenda. Furthermore, a congress held by the nationalists of Cairo, from 15 to 22 February 1947 about the case of North Africa, ended with the creation of a Maghrebi office, replacing the representation of Neo-Destour. Its essential goals were to reinforce resistance movements inside colonized countries but also abroad, aiming to get the United Nations involved. Habib Thameur was designated as head of this organisation.[87] In March 1947, Bourguiba came back to Cairo and, for nearly a year, tried to convince Arab leaders to introduce the Tunisian Case to the UN.[88] In addition, he endowed Neo-Destour of its second representation in the Arab World, in Damascus, led by Youssef Rouissi, who knew the Syrians well. Nevertheless, progress were slow and Bourguiba's journey in Middle-East ended only with a substantial material assistance on behalf of Saudi Arabia, neither Iraq nor Syria nor Libya wanting to support his cause.[85]

Upon the disinterest of the members of Arab League for Maghrebi struggle, while the war in Palestine was the center of all attention and efforts, the union of different nationalist movements seemed to be the better way to get their requests heard. But soon, divisions appeared among Tunisians, Moroccan and Algerians, preventing common agreements.[89] On 31 May 1947, the arrival of Abdelkrim al-Khattabi from exile revived the movement.[90] Under his impulse, the committee of liberation of North Africa was founded on 5 January 1948.[91] The values of the committee were Islam, Pan-arabism and total independence of Maghreb with the refusal of any concessions with the colonizer.[92] Headed by Khattabi, designated president for life, Bourguiba was secretary-general. However, despite the status of the Moroccan leader, the committee was not as successful as the Office of Arab Maghreb. Obsessed by the Palestinian issue, the leaders of the Arab League were refusing to support the Maghrebi issue, whose problems deepened with a financial crisis.

While Khattabi favored an armed struggle, Bourguiba was strongly opposed, defending the autonomy of the Tunisian nationalism, which soon divided the Maghrebi committee.[93] His moderate ideas made him infamous among the other members of the committee, whose numbers were increasing day after day.[94] To discredit Bourguiba, rumors were spread that he received, underhand, funding from many Arab leaders and that he had special relationships with the French embassy in Egypt.[95] During his trip to Libya, in spring 1948, the committee removed him from his duties of secretary-general. Noting that there were too much ideological differences between the Committee and himself, it only contributed in discrediting his relationship with Cairo Tunisians such as Thameur, with whom his relationship was deteriorating.[96][97]

Even in Tunis, his exile in Middle-East, weakened the Tunisian leader: Apart from the ascending of Moncefism, after the removal and exile of Moncef Bey in Pau, the party restructured around Ben Youssef with the help of the newly created Tunisian General Labour Union by Farhat Hached.[98] Even though elected president of the party, during the Congress of Dar Slim, held clandestinely in Tunis in October 1948, he was now assisted by three vice-presidents whose goal was to limit the power of the president: Hedi Chaker in Tunis, Youssef Rouissi in Damascus and Habib Thameur in Cairo.[99] Having gone to the Egyptian capital to support the national struggle abroad, Bourguiba found himself, four years later, weakened politically and marginalized among the Maghrebi Committee in Cairo, exiled and isolated from Tunisia. Aware of the importance of the struggle inside the country, he decided to regain Tunis on 8 September 1949.[32]

1949–1956: Fighting for independence

[edit]Failure of negotiations with France

[edit]

When he returned to Tunisia, Bourguiba decided to start a campaign to regain control of the party. From November 1949 to March 1950, Bourguiba visited cities such as Bizerte, Medjez el-Bab and Sfax and saw his popularity increase, thanks to his charisma and oratory skills.[100] Once he had achieved his goals, he reappeared as the leader of the nationalist movement and therefore, decided to travel to France, ready for negotiations. On 12 April 1950, he landed in Paris to raise the Tunisian issue by mobilizing public opinion, media and politicians. Three days later, he gave a conference in Hôtel Lutetia to introduce the main nationalist requests, which he defined in seven points, stating that "these reforms destined to lead us towards independence must reinforce and strengthen the spirit of cooperation [...] We believe that we are a country too weak militarily and too strong strategically to dispense with the help of a great power, which we would want to be France".[101]

His speech quickly attracted the opposition of both the "Preponderants" and the pan-Arab circles who were strongly against his stepwise policy and his collaboration with France. Therefore, Bourguiba felt that an endorsement from the bey was not only necessary, but vital. Thereby, he sent Ben Youssef and Hamadi Badra, convince Muhammad VIII al-Amin bey to write a letter to Vincent Auriol. On 11 April 1950, the letter was written, reminding the French president of the Tunisian requests sent ten months ago and asking for "necessary substantial reforms".[102] At last, the French government reacted, on 10 June, with the designation of Louis Perillier as resident-general, who, according to then-minister for foreign affairs, Robert Schuman, "shall aim to lead Tunisia towards the full development of its wealth and lead it towards independence, which is the end goal for all territories within the French Union".[103] However, the word "independence" is soon replaced by "internal autonomy".[104] Despite that, Bourguiba was eager to support Périllier's reform process. Soon, he was satisfacted with his flourishing results of his visit to Paris because the Tunisian case became one of the most debated issues by both public opinion and parliament.[105]

In Tunis, Périllier, endorsed by Bourguiba, favoured the constitution of a new Tunisian cabinet, led by M'hamed Chenik with neo-destourian participation to mark the liberal turning decided by France. On 17 August 1950, the cabinet was invested counting among its members three ministers from Neo-Destour.[106][107] However, the French Rally of Tunisia, opposed to any reform, succeeded to pressure both the colonial government in Tunisia and the French authorities in France, to get the negotiations restrained.[108] Périllier ended up yield to pressure and stated on 7 October that "It is time to give a break to reforms", which did not please the Tunisian government.[109] Reacting to the statement, riots started in Enfida and ended with several dead and injured.[110] Even though Bourguiba tried to pacify the atmosphere of tension, his strategy of collaboration with France was contested by the majority of Tunisian leaders who considered it indefensible, mainly after the adoption of deceiving reforms, on 8 February 1951.[111]

Upon the blocking of negotiations with France, Bourguiba was convinced that there was nothing to do and decided to travel around the world, aiming to gain support for the Tunisian struggle. From 1950, even though he continued to negotiate with France, Bourguiba was considering the use of arms and violence to get things done.[112] Therefore, he asked for the help of Ahmed Tlili to create a national resistance committee, with ten regional leaders responsible for the formation of armed groups and arms depot.[113] During his visit to Pakistan, he did not exclude the use of popular mobilization to obtain independence. If he was introducing himself as an exiled militant back in his journey to Middle-East, he was now a leader of a major party among the Tunisian government. This new status permitted him to meet officials of all the countries he had visited: He met with Indian Prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru in New Delhi and the Indonesian president Sukarno. During his interviews, he urged his interlocuters to introduce the Tunisian issue to the United Nations, recalling his failed attempt to introduce it back in the September 1951 session.[112]

Since his last meeting with Ahmed Ben Bella, in January 1950, Bourguiba was more and more convinced that an armed struggle was inevitable. Thus, in Cairo, he charged a group of people called Les Onze Noirs to train people, fundraise and gather weapons.[112] Disappointed in the support promise of Egyptian and Saudi authorities, Bourguiba traveled to Milan, where the congress of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions opened in July 1951. Thanks to Farhat Hached, Bourguiba obtained an invitation to take part in the event. There, he was invited by American unionists of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) to their gathering, which took place in San Francisco in September 1951. Between July and September, he travelled to London then Stockholm.[112] His journey in the United States ended in mid-October before he flew to Spain, Morocco, Rome and Turkey. There, he admired the work of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in building a secular modern state. He then wrote to his son: "I have put a lot of thought into it. We can get to the same results, even better by less drastic means, which reflect more widely the soul of the people".[114]

While Bourguiba proceeded with his world tour, the situation in Tunisia worsened: The promised reforms were blocked and the negotiations continued in Paris. On 31 October, as prime minister acting in the name of the bey, Chenik delivered officially to Schuman a memorandum summarizing the essential Tunisian requests regarding the intern autonomy.[115] On 15 December, Bourguiba landed in Paris where he heard the answer of Schuman: The statement of 15 December, affirmed the principle of co-sovereignty and the "final nature of the bond that links Tunisia to France".[114][116][108] As for Bourguiba, it was then sure that endless and resultless negotiations were over. He stated to the AFP that "A page of Tunisian history is turned. Schuman's response opens a repression and resistance era, with its inevitable procession of mourning, tears and resentment [...] Exasperated, disappointed, out of patience, the Tunisian people will show the entire world that they are mature enough for freedom". Finally, he addressed the United States saying that "Their freedom [the Tunisian people] is a necessary condition for the defense of the free world in the Mediterranean sea and everywhere else to secure peace".[114]

Armed struggle

[edit]

While the Tunisian delegation got back to Tunis upon the blocking of negotiations, Bourguiba remained in Paris where he judged essential to make contacts in this confrontation era. His goals consisted in obtaining funds and arms for the armed struggle but also convince the rest of the world to introduce the Tunisian issue in the United Nations. However, due to the refusal of his request by numerous diplomats, he decided to provoke the complaint and force the fight. Upon his return to Tunisia, on 2 January 1952, he hurried to meet the bey and Grand Vizier Chenik, who he urged to introduce the request to the United Nations Security Council, faking that he obtained the support of the American delegate if Tunisia complained.[117] If they were hesitating at first, they soon gave way to Bourguiba. Meanwhile, the nationalist leader travelled all around the country to inform the people of this issue. His speeches became more and more violent and ended with his statement in Bizerte, on 13 January, where he denounced the cabinet if a delegation did not fly immediately to the U.N.[117] The request was signed on 11 January in Chenik's house by all the ministers of the cabinet, in the presence of Bourguiba, Hached and Tahar Ben Ammar.[118] On 13 January, Salah Ben Youssef and Hamadi Badra flew to Paris, where they intended to desposit the complaint.[119]

France did not appreciate the move and reacted with the nomination of Jean de Hauteclocque as new resident-general.[120] Known for his radical hard way, he decided to prohibit the congress of Neo-Destour that should have been held on 18 January and proceeded with the arrest of activists, such as Bourguiba.[121][103] The congress, which was held clandestinely, favored the continuation of the popular unrest.[122][117] The following repression soon started a greater unrest.[123] Meanwhile, Bourguiba was transferred to Tabarka where he kept a surprising flexibility and freedom of movement. He soon understood De Hautecloque's maneuvers as his desire for Bourguiba to exile himself in nearby Algeria. He was even interviewed by Tunis Soir and was visited by Hédi Nouira and Farhat Hached.[124]

Following the uprising in Tunisia, Afro-Asian country members of the UN finally answered the request of Ben Youssef and Badra, introducing the Tunisian case to the Security Council, on 4 February 1952. As for Bourguiba, "it depends on France to make this appeal moot by loyally accepting the principle of internal autonomy of Tunisia".[125] But on 26 March, upon the strong refusal of the bey to discharge Chenik's cabinet, De Hauteclocque placed Chenik, El Materi, Mohamed Salah Mzali and Mohamed Ben Salem under house arrest in Kebili while Bourguiba was sent to Remada.[126][127] A new cabinet, led by Slaheddine Baccouche took over.

Aiming to weaken the nationalist movement, De Hautecloque separated Bourguiba and his exile companions. Therefore, he was sent on the island of La Galite, on 21 May 1952. Settled in an old abandoned fort, he had health problems, caused by humidity and age[clarification needed]. In France, the opponents to a Tunisian compromise discredited Bourguiba whom they accuse of preparing the armed struggle while negotiating with their government, in an article of Figaro published on 5 June.[128] Meanwhile, the bey remained alone against the resident-general, resisting the pressures to approve reforms, judged "minimal" by the nationalists, which delighted Bourguiba. In the country, despite the unity of the people, De Hauteclocque pressured the adoption of reforms.[129] Therefore, many assassinations took place: Farhat Hached is murdered on 5 December 1952 by La Main rouge.[130] Bourguiba, deprived of posts and newspapers called for the intensification of the resistance.[131]

In these conditions, the French government decided to replace De Hauteclocque with Pierre Voizard as resident-general, on 23 September 1953. Trying to appease the uprising, he lifted the curfew and newspaper censorship but also freed nationalist leaders.[132] Furthermore, he replaced Baccouche with Mzali and promised new reforms which soon seduced the Tunisian people.[133] Nevertheless, Bourguiba remained detained in La Galite Island with, however, a softening of imprisonment conditions. If the reforms legislated the principle of co-sovereignty, Bourguiba judged these measures to be outdated. But he was worried of the cleverness of Voizard, whose methods seemed to be more dangerous than the brutality of De Hauteclocque. This obvious liberalism seduced numerous Tunisians tired of this violence climate which had imposed itself for too long but divided the Neo-Destour between those who supported the policy of the new resident-general and those who didn't.[131] The differences among the party deepened more and more upon Voizard's plans. Both Bourguiba and Ben Youssef remained strongly opposed to the collaboration between the bey and the residence. After a period of hesitation about what to do with the reform project, the Neo-Destour gave orders to resume actions of resistance.[134] Therefore, the Fellaghas decided to resume the attacks in the countryside.[135]

Voizard attempted to bring back peace by pardoning half the 900 Tunisian convicted on 15 May and decided to put an end to the two-year exile of Bourguiba in La Galite. On 20 May 1954, he was transferred to Groix Island but remained strongly firm on his positions, stating that "the solution to the Tunisian problem was simple [...] The first step was to give Tunisia its internal autonomy, the economic, strategic, cultural rights of France in these fields being respected. Now, this a real confrontation".[136][137] But these measures changed nothing: As the delegates of the French Rally of Tunisia requested in Paris that Bourguiba must be "unable to resume a campaign of agitation", the Grand Vizier Mzali was almost killed in a failed assassination attempt. Despite the repression he instituted, Voizard lost control of the situation and faced the rage of certain Tunisians opposed to colonists. On 17 June, Mzali resigned from office without any successor left to take charge.[138] This resignation did not leave an available interlocutor to negotiate with the newly invested cabinet of Pierre Mendès France on 18 June, six weeks after the defeat of French forces in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu.[103] The new head of government stated upon his designation that he will not "tolerate any hesitation or reluctance in implementing the promises made to people who had confidence in France that had promised to put them in condition to manage their own affairs".[139]

Internal autonomy agreements

[edit]On 21 July, Bourguiba was transferred into The Château de La Ferté in Amilly (110 kilometers from Paris) on the orders of Mendès France to preparing the upcoming negotiations.[140] On 31 July, the new French prime minister travelled to Tunis and gave his famous speech in which he stated that the French government unilaterally recognizes the internal autonomy of Tunisia. Meanwhile, Bourguiba received representatives of Neo-Destour in Paris, under the supervision of the Direction centrale des renseignements généraux.[32] In Tunis, a new cabinet led by Tahar Ben Ammar was formed to negotiate with the French authorities. Four members of Neo-Destour were made ministers.

On 18 August, the negotiations started. Bourguiba was given the right to settle in the hotel where the Tunisian delegation lodged. Thus, he received detailed reports of the delegation talks while he gave them instructions.[32] However, the situation in the country worsened with the pursuing of the armed struggle. Likewise, the first day of negotiations started with a serious clash between military and rebels.[141] Everybody was convinced that only a watchword from the Neo-Destour would convince the fellaghas to stop the fight. Nevertheless, the party was ripped between those who wanted the unrest to continue and those who wanted it to stop. Bourguiba wanted the fight to be over to hasten the negotiations for the internal autonomy. He had among the party numerous supporters of the stepwise policy of his. But many were those who wanted immediate independence. In this context, he appeared to be the only one to have the necessary authority to resolve the problem.[142]

Mendès France, convinced that the current troubled situation threatened his colonial policy, was eager to meet Bourguiba. Therefore, he was transferred to Chantilly, in October, where he was from that moment lodged. The interview between both men remained secret and ended with Bourguiba's promise to end the unrest in the country.[142] Nevertheless, the beginning of the armed civil uprising in Algeria on 1 November 1954, did not improve the current situation. Indeed, the rage of French politicians, who accused the Tunisian fellaghas to collaborate with the Algerian rebels, slowed the negotiations. The situation worsened on 11 November, when the French government, addressed an ultimatum to the Tunisian government, announcing that the talks would stop until the unrest in Tunisia was over.[143]

On 14 November, under the pressure of Bourguiba, the Nation Council of Neo-Destour, invited both French and Tunisian government to "find a solution to the fellaghas issue guaranteeing in an explicit way their backup, their personal freedom and that of their families". On 20 November, an agreement was concluded. It said firstly that "the Tunisian government solemnly invite the fellaghas to deliver their weapons to the French and Tunisian authorities" and secondly that "the resident-general of France and the Tunisian government vouch that under the agreement between them, the fellaghas shall not be disturbed or prosecuted and that measures be taken to facilitate their rehabilitation to normal life and that of their families".[144] Furthermore, Bourguiba intervened a second time to reassure the resistance leaders of his confidence in Mendès France and reiterated his guarantee of their security. After two years of unrest, the discussions can finally resume.[142]

Nevertheless, the negotiations for the internal autonomy were not unanimous: On 31 December 1954, while in Geneva, Ben Youssef, who wanted immediate independence, denounced the discussions and challenged the stepwise policy adopted by Bourguiba.[145] Knowing that his statement would attract many favorable activists, mostly after the fall of the Mendès France cabinet on 6 February 1955, causing panic among the moderate faction of the party. Nevertheless, their fears were at ease with the arrival of Edgar Faure as head of the French government on 23 February. Faure assured his commitment to pursue the negotiations started by his predecessor. With Faure's promise, it was necessary for the Neo-Destour to bring the two leaders closer and therefore, set forth a strong united nationalist front to France. However, Ben Youssef did not agree with the talks, denouncing any negotiation that would not lead immediately to the independence of the whole Maghrebi people, supported in his position by the Algerians.[146]

On 21 April 1954, an interview between Faure and Bourguiba aimed to conclude the agreements for the internal autonomy.[147] Hearing the news while participating in the Bandung Conference, Ben Youssef rejected the agreements which he judged contrary to the principle of internal autonomy and indicated to a journalist that he "did not want to be Bourguiba's subordinate anymore".[148] As for him, the Tunisian people must be opposed to the conventions and demand immediate independence without any restrictions. Despite attempts to conciliate both leaders, the break between the two men was final.[149] Bourguiba, however, tried to ease tensions and persuade Ben Youssef to get back to Tunisia, but in vain, the secretary-general of the party eager to remain in Cairo, until further notice.[146]

On 1 June 1955, Bourguiba returned triumphant to Tunisia on board of the Ville d'Alger boat. Sailing from Marseille, he landed in La Goulette.[150] On his own, he advanced to the bridge, waving his arm raising a large white tissue to greet the crowd. "We were hundreds of millions [sic] coming to cheer him, interminably in a huge frenzy", testified his former minister Tahar Belkhodja.[74] On 3 June, the internal autonomy conventions were signed by Ben Ammar and Faure, Mongi Slim and the French minister for Tunisian and Moroccan affairs, Pierre July.[151][152]

After the ratification of the conventions, on 3 June, the consultations aiming to form the first cabinet of the internal autonomy started. However, Bourguiba was not to lead it. Beside the fact that it was too soon for France to have the "Supreme Commander" at the head of the Tunisian government, he stated that power did not attract him and judged it to be still early to hold an office within the state. Therefore, it was Tahar Ben Ammar who was chosen once again to lead the government. Likewise, the Neo-Destour prevails. It was the first time since 1881, that the Tunisian cabinet did not include a French member. While giving speeches all around the country, Bourguiba insisted on this fundamental fact, demonstrating that the conventions gave a large autonomy to the Tunisian people in management of its affairs. Defending his strategy, he must not leave the field open to the maximalism of Ben Youssef, supported by the Communists and the Destour.[153]

Fratricidal struggles

[edit]

On 13 September, Ben Youssef returned to the country from Cairo.[32] Trying to bring back peace and convince Ben Youssef to reconsider his positions, Bourguiba went to the airport welcoming his "old friend". But his efforts were in vain and peace was short: Ben Youssef did not wait too long to criticize the modernism of the "supreme commander" who trampled the Arab-Muslim values and invited Bourguiba's opponents to resume the armed struggle to free the whole Maghreb.[154][155] Reacting to Ben Youssef's statements, the French High Commissioner judged them to be outre while the Neo-Destour Leadership impeached Ben Youssef of all his charges, during a meeting convened by Bourguiba. The exclusion was voted but the seriousness of the situation led them to keep the decision secret until further notice. It was finally made public on 13 October, surprising many activists who judged the decision to be too important to be taken by a mere meeting. Many factions, supportive of Ben Youssef, were opposed to the decision and declared Ben Youssef to be their rightful leader.[156][157]

On 15 October, Ben Youssef reacted to the leadership's decision in a meeting organized in Tunis: He declared the party leaders illegal and took the direction of a "general Secretariat" which he proclaimed being the only legitimate leadership of the Neo-Destour. The pan-Arab scholars of Ez-Zitouna, feeling marginalized by the occidental trend of the party, showed a great support for the conservative trend who had just being created. The country started to twitch once again. Ben Youssef multiplied his tours around the country facing the sabotage attempts of Bourguiba's followers.[155] However, cells supportive of Ben Youssef were creating everywhere, while many Neo-Destourian activists remained in an expectant hush, waiting to see who of the two leaders will have the last word.[158] Therefore, Bourguiba started an information campaign which was successful, especially in Kairouan, who was seduced by the leader's charisma and decided to rally his cause.[159]

In this context, a congress was held in November 1955 to choose which of the two leaders would have the last word. Though Ben Youssef decided not to attend, Bourguiba ended up winner of the debate and obtained the endorsement of the delegates. Therefore, his opponent was expelled from the party and the internal autonomy conventions were approved.[160][161] Outraged by the congress aftermath, Ben Youssef organized numerous meetings to demonstrate his influence. Inside the country, he gained the support of fellaghas who reprised the uprest. Bourguibist cells and French settlers were attacked. As for the fellaghas, it was necessary to get immediate independence, even with weaponry and put an end to Bourguiba's power. The 1 June united Tunisia was definitely torn apart: Those who rallied Bourguiba and those who opposed him and joined Ben Youssef.[162]

This troubled situation generated an era of civil war.[163] Killings, arbitrary detention, torture in illegal private prisons, fellagas who took up arms against the Tunisian forces, abduction by militias and attacks by local adversaries caused dozens of dead and many injured.[164] Due to this situation, French authorities decided to speed up the implementation of the autonomy agreements by transferring the law enforcement responsibility to the Tunisian government starting from 28 November. This decision did not please Ben Youssef who feared the jeopardizes of minister of the interior Mongi Slim.[165] To thwart the decisions of the Congress of Sfax, he called for holding a second congress as soon as possible. However, he faced opposition from the Tunisian government.[166] Soon, Ben Youssef was charged for inciting rebellion. Slim informed Ben Youssef that he were to be arrested by Tunisian policemen, which led him to flee out of the country. Clandestinly, he went to Tripoli, Libya, by crossing the Libyan-Tunisian borders on 28 January 1956.[167][162] The following morning, three newspapers endorsing him were seized and 115 persons were arrested all around the country. The government decided to create a special criminal court, known as the High court to judge the rebels. Meanwhile, Ben Youssef insisted on his followers to resume the fight. The regional context was in his favor because the Maghreb ablazed for the liberation struggle and nationalists were quickly disappointed by the conventions of internal autonomy that left only a few limited powers to Tunisians.[168]

Convinced that he must act, Bourguiba flew to Paris in February 1956 aiming to persuade the reluctant French authorities to start negotiations for total independence. On 20 March 1956, around 5:40 pm in the Quai d'Orsay, the French minister of foreign affairs, Christian Pineau stated that "France solemnly recognizes the independence of Tunisia" and signed the Independence protocol along with Tahar Ben Ammar.[169][170][171] The clauses put an end to Bardo Treaty. However, France kept its military base of Bizerte for many years. On 22 March, Bourguiba returned to Tunisia as the great winner and stated that "After a transition period, all french forces must evacuate Tunisia, including Bizerte".[172]

1956–1957: Prime minister of the Kingdom of Tunisia

[edit]

Following independence, proclaimed on 20 March 1956, a National Constituent Assembly was elected, on 25 March, in order to write a constitution. Therefore, Bourguiba ran to represent the constituents of Monastir, as the Neo-Destour candidate. On 8 April, the assembly held its opening session, chaired by M'hamed Chenik while Al-Amine bey attended the ceremony. The same day, Bourguiba was elected as Speaker of the National Constituent Assembly and gave a speech, summarizing his ambitions for the country:

We cannot forget that we are Arabs, that we are rooted in the Islamic civilization, as much as we cannot neglect the fact of living in the second part of the 20th century. We want to take part in the march of civilization and take a place deep into our time.[173]

With this new start, Tahar Ben Ammar's mission as head of government had ended and therefore, he delivered his resignation to al-Amine bey. Therefore, the Neo-Destour nominated Bourguiba to be their candidate for the office, on 9 April. Bourguiba accepted and was officially invited by the bey, three days after his election as head of the assembly, to form a cabinet. On 15 April, Bourguiba introduced his cabinet including one deputy prime minister, Bahi Ladgham, two state ministers, eleven ministers and two secretaries of state. Furthermore, Bourguiba combined the offices of Minister of Foreign Affairs and Defense.[174] Therefore, he became the 20th Head of government of Tunisia and the second of the Kingdom of Tunisia. He expressed, once officially inaugurated as Prime minister, his will to "enforce sovereignty bases by perfecting the means inside the country and abroad, put this sovereignty only under the service of Tunisian's interests, implementing a bold and judicious policy to free national economy from the chains of immobilism and unemployment."[175]

As Prime minister, Bourguiba worked to secure total independence. Upon his nomination, the police switched from French management to Tunisian command, as he nominated Ismaïl Zouiten to be chief of police and the first Tunisian to hold this office. Meanwhile, French gendarmerie was replaced by the National Guard, on 3 October 1956.[176] Bourguiba also reorganized Tunisia's administrative divisions, creating a modern structure made of 14 governorates, divided in delegations and managed by appointed governors.[177] Bourguiba also pursued negotiations with France in order to have full control over diplomacy, as France still had a say over foreign policy until an agreement was found. Despite that, Bourguiba created a Tunisian minister of Foreign affairs on 3 May and invited other countries to establish embassies and diplomatic relations. Therefore, he appointed 4 ambassadors in Arab countries and approved the United States and Turkey's decision to start a diplomatic mission in Tunisia. Under pressure, France agreed with the opening of respective embassies and signed an agreement with the Tunisian government on 16 May. On 12 November, Tunisia became an official United Nations member.[178]