Brussels Town Hall

| Brussels Town Hall | |

|---|---|

Town Hall of the City of Brussels's main façade seen from the Grand-Place/Grote Markt | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Town hall |

| Architectural style | |

| Location | Grand-Place/Grote Markt |

| Town or city | 1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region |

| Country | Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°50′47″N 4°21′6″E / 50.84639°N 4.35167°E |

| Construction started | 1401 |

| Completed | 1455 |

| Height | 96 metres (315 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Jean Bornoy, Jacob van Thienen, Jan van Ruysbroek |

| Engineer | Guillaume de Voghel |

| Part of | La Grand-Place, Brussels |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 857 |

| Inscription | 1998 (22nd Session) |

The Town Hall (French: Hôtel de Ville, pronounced [otɛl də vil] ⓘ; Dutch: Stadhuis, pronounced [stɑtˈɦœys] ⓘ) of the City of Brussels is a landmark building and the seat of that municipality of Brussels, Belgium. It is located on the south side of the Grand-Place/Grote Markt (Brussels' main square), opposite the neo-Gothic King's House or Bread House[a] building, housing the Brussels City Museum.[1]

Erected between 1401 and 1455, the Town Hall is the only remaining medieval building of the Grand-Place and is considered a masterpiece of civil Gothic architecture and more particularly of Brabantine Gothic.[2] Its three classicist rear wings date from the 18th century. Since 1998, is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as part of the square.[3][4]

This site is served by the premetro (underground tram) station Bourse/Beurs (on lines 3 and 4), as well as the bus stop Grand-Place/Grote Markt (on line 95).[5]

History

[edit]Gothic Town Hall

[edit]The Town Hall (French: Hôtel de Ville, Dutch: Stadhuis) of the City of Brussels was erected in stages, between 1401 and 1455, on the south side of the Grand-Place/Grote Markt, transforming the square into the seat of municipal power. Due to the square's tumultuous history (see details below), it is also its only remaining medieval building.[2]

The oldest part of the present building is its east wing (to the left when facing the front). This wing, together with a shorter tower, was built between 1401 and 1421. The architect and designer is probably Jacob van Thienen with whom Jean Bornoy collaborated.[6] Initially, future expansion of the building was not foreseen, however, the admission of the craft guilds into the traditionally patrician city government apparently spurred interest in providing more room for the building. As a result, a second, somewhat longer wing was built on to the existing structure, with the young Duke Charles the Bold laying its first stone in 1444.[6] The architect of this west wing is unknown. Historians think that it could be Guillaume (Willem) de Voghel who was the architect of the City of Brussels in 1452, and who was also, at that time, the designer of the Aula Magna at the Palace of Coudenberg.[7]

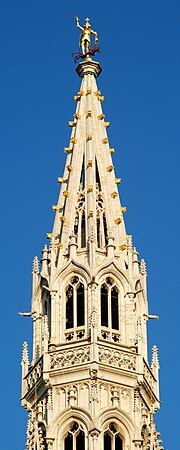

The 96-metre-high (315 ft) tower in Brabantine Gothic style is the work of Jan van Ruysbroek, the court architect of Philip the Good.[6][8] By 1455, this tower, replacing the older one, was complete. Above the roof of the Town Hall, the square tower body narrows to a lavishly pinnacled octagonal openwork. At its summit stands a 2.7-metre-tall (9 ft)[b] gilt metal statue of Saint Michael, the patron saint of the City of Brussels, slaying a dragon or demon.[6][9] The tower, its front archway and the main building's façade are conspicuously off-centre relative to one another. According to a legend, the architect of the building, upon discovering this "error", leapt to his death from the tower.[10] More likely, the asymmetry of the Town Hall was an accepted consequence of the scattered construction history and space constraints.

-

Brussels' Town Hall, engraving by Melchisedech van Hoorn, 1565

-

View of the Grand-Place in Brussels and the Town Hall, Jan Mommaert, 1594

-

Detail from a map of Brussels by Martin de Tailly, possibly by Jacques Callot, 1640

-

Brussels' Town Hall, engraving by Abraham van Santvoort after Leo van Heil, c. 1650

Destruction and rebuilding

[edit]On 13 August 1695, during the Nine Years' War, a 70,000-strong French army under Marshal François de Neufville, duc de Villeroy, began a bombardment of Brussels in an effort to draw the League of Augsburg's forces away from their siege on French-held Namur in what is now Wallonia. The French launched a massive bombardment of the mostly defenceless city centre with cannons and mortars, setting it on fire and flattening the majority of the Grand-Place and the surrounding city. The resulting fire completely gutted the Town Hall, destroying the building's archives and art collections, including paintings by Rogier van der Weyden.[11][12][13] Only the stone shell of the building remained standing.[14][11] That it survived at all is ironic, as it was the principal target of the artillery fire.[15]

After the bombardment, the municipal government funded the Town Hall's repair, raising the money by selling houses and land. The interior was soon rebuilt and enlarged by the architect-sculptor Cornelis van Nerven, who added three rear wings in the Louis XIV style over the ruins of the former inner cloth market (Halle au Drap), from 1706 to 1717,[7] transforming the L-shaped building into its present configuration: a quadrilateral with an inner courtyard.[16] Until 1795, these wings housed the States of Brabant, the representation of the three estates (nobility, clergy and commoners) to the court of the Duke of Brabant.[7][16]

-

The Grand-Place in flames during the bombardment of Brussels in 1695. The Town Hall is on the left.

-

The Town Hall burning during the bombardment

-

The surroundings of the Town Hall after the bombardment

19th-century restorations

[edit]

The Town Hall underwent many restoration campaigns throughout the 19th century, first under the direction of the architect Tilman-François Suys, starting in 1840.[17] The interior was later revised by the architect Victor Jamaer from 1860, in the style of his mentor Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.[18][17] Jamaer was the City of Brussels' architect and also reconstructed the King's House. The interior is now dominated by neo-Gothic: the Maximilian Room, the States of Brabant Room and their antechamber with tapestries depicting the life of Clovis,[19] the splendid Municipal Council Room, the likewise richly furnished ballroom and the Wedding Room (formerly the courtroom).[20][21]

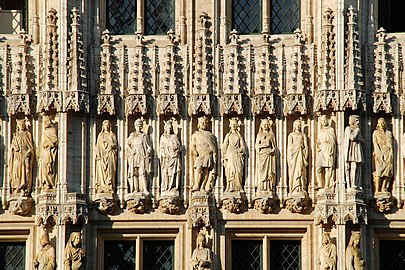

It was also at this time that most of the Town Hall's statues were made. Indeed, before then, the Town Hall was not adorned like it is today with countless statues, with the exception of corbels, representations of eight prophets above the portal, and a few statues located at the corner turrets.[18] Jamaer reworked the façade by adding non-existent niches, as well as a gallery and a new portal. Between 1844 and 1902, nearly three hundred statues in Caen and Échaillon stone, created by famous artists, including Charles Geefs, Charles-Auguste Fraikin, Eugène Simonis and George Minne, were executed.[17] The interior rooms were replenished with tapestries, paintings, and sculptures, largely representing subjects of importance in local and regional history, such as a monumental bronze statue of Saint Michael created by Charles van der Stappen in the entrance.[21]

Contemporary history

[edit]

The Town Hall not only housed the city's magistrate, but also the States of Brabant until 1795. In 1830, the provisional government operated from there during the Belgian Revolution, which provoked the separation of the Southern Netherlands from the Northern Netherlands, resulting in the formation of Belgium as it is known presently.

At the start of World War I, as refugees flooded Brussels, the Town Hall served as a makeshift hospital.[22] On 20 August 1914, the occupying German army arrived at the Grand-Place and hoisted a German flag at the left side of the Town Hall.[22]

The Town Hall was designated a historic monument on 9 March 1936, at the same time as the King's House.[23] It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998 as part of the registration of the Grand-Place.[4]

Architecture

[edit]Tower

[edit]The tower is made up of two very different parts that nevertheless form a harmonious ensemble: a square base dating from the first phase of construction and a lantern tower built by Jan van Ruysbroek nearly half a century later.[6][8]

The square base is pierced by an ogival portal surmounted by the same decoration as the left wing: mullioned windows on the first floor, row of statues, then mullioned windows inscribed under a trefoil tympanum on the second floor. This square tower is then extended by two floors, each pierced by a pair of ogival bays on the side facing the Grand-Place.

Next comes the finely openwork octagonal lantern tower, supported at its base by four buttressed turrets, also octagonal. It has three levels pierced with elegant openwork ogival bays and adorned with a profusion of arcades, parapets and gargoyles, and ends with a remarkable openwork spire enhanced with gilding and surmounted by the statue of Saint Michael, the patron saint of the City of Brussels, slaying a dragon or demon.[6][9]

-

Overview of the tower

-

The upper part of the tower

-

The spire and the statue of Saint Michael

-

View from the Rue Chair et Pain/Vlees-en-Broodstraat

Statue of Saint Michael

[edit]The statue of Saint Michael is a work by Michel de Martin Van Rode, and was placed on the tower in 1454 or 1455.[7][6][9] It was restored several times before being removed in the 1990s and replaced by a copy. The original is kept in the Brussels City Museum, located in the King's House or Bread House building across the Grand-Place.

This statue is made of arranged metal plates and not brassware. Up close, it looks clumsy and ill-proportioned, but these distortions disappear when viewed from afar, from which it appears elegantly proportioned.[24]

The dragon symbolises the Devil or Satan according to the Apocalypse:

- Revelation, 12, 9: "Thus was overthrown the great Dragon, the primitive Serpent, called Devil and Satan."

- Revelation, 20, 2: "I saw another angel come down from heaven: he held in his hand the key of the abyss and a great chain. He mastered the Dragon, the primitive serpent, who is none other than the Devil and Satan."

-

Restoration of Saint Michael's statue in the Town Hall in 1896

-

The original statue kept in the Brussels City Museum

-

The copy of the statue placed at the top of the tower

Main façade

[edit]The main façade consists of two asymmetrical wings framing the tower and terminated by corner turrets. Each wing consists of arcades, a balcony, two stories pierced by large mullioned windows and is surmounted by a high saddleback roof pierced by numerous hipped dormers. The octagonal corner turrets have several levels whose faces are decorated with trefoil arches. Each level ends with eight gargoyles arranged radially and is surmounted by a walkway with an openwork parapet. The last level is crowned by a stone spire decorated with foliage and surmounted by a weather vane.

The façade is decorated with numerous statues representing the local nobility (such as the Dukes and Duchesses of Brabant and knights of the Noble Houses of Brussels), saints, and allegorical figures. The present sculptures are mainly 19th- and 20th-century reproductions or creations; the original 15th-century ones are also in the Brussels City Museum.[25][26] Each of these statues rests on a historiated corbels and is sheltered under a finely chiselled stone canopy surmounted by a pyramid-shaped stone pinnacle decorated with foliage pattern and topped with a finial.

-

Statues of Dukes and Duchesses of Brabant

-

The windows of the second floor of the right wing

Portal

[edit]The base of the tower is pierced by an ogival portal surmounted by a tympanum depicting Saint Michael surrounded by Saint Sebastian, Saint Christopher, Saint George and Saint Géry (Gaugericus) who, according to legend, erected a chapel that would be at the origin of the City of Brussels.

On either side of this portal stand statues of the four cardinal virtues: Prudentia ("Prudence") and Justitia ("Justice") on the left, Fortitudo ("Fortitude") and Temperantia ("Temperance") on the right. The statues of the virtues are supported by very expressive historiated corbels.

The tympanum, the statues and the corbels do not date from the Gothic period but from the 19th-century restorations.

Arcades

[edit]The base of the façade is adorned with a gallery of arcades. These arcades are highly asymmetrical as mentioned above: the left wing has eleven arches (including a blind arch located under the corner turret) while the right wing has only six. These ogival arcades have an outer curve decorated with cabbage leaves, a typical motif of the Brabantine Gothic style. Each of them is topped with a finial, also adorned with cabbage leaves, and is surmounted by an arcade of trefoil arches.

The arches are supported by pillars adorned with statues of knights and squires of the Noble Houses of Brussels.[18] These statues rest on often very expressive historiated corbels, among which can be noted a vielle and a gittern player.

-

Left wing arcade

-

Knight of the Noble Houses of Brussels

-

Fleuron, cabbage leaves and arcature of trefoil arches

-

Vielle player

Porch

[edit]The gallery in the left wing houses a porch made up of a staircase, a stone balustrade pierced with quadrilobed motifs and two columns each surmounted by a seated lion bearing the coat of arms of Brussels. These lions were sculpted by G. De Groot in 1869, during the 19th-century restorations.[27]

On either side of the steps, the pillars are replaced by historiated corbels representing two tragic scenes involving schepen (aldermen) of the City of Brussels:

- On the left, the legend of Herkenbald or Archambault,[27] the Brussels version of the honest judge who, on his deathbed, sentenced his nephew to death, convicted of rape, before executing him with his own hands because the officer in charge of the execution exempted him from the sentence;

- On the right, the attack on Everard 't Serclaes by the henchmen of the Lord of Gaasbeek, following which he was transported to the L'Étoile (Dutch: De Sterre) guildhall located to the left of the Town Hall, before dying there on 31 March 1388.

-

The porch

-

Front porch lion

-

The legend of Herkenbald

-

The assassination of Everard 't Serclaes

Gargoyles

[edit]The various façades of the Gothic Town Hall (on the Grand-Place but also on the courtyard side) are adorned with innumerable very expressive gargoyles depicting human beings, animals or fantastic creatures. Similarly, the octagonal corner turrets feature a series of eight gargoyles on each floor.

-

Gargoyle with human face

-

Fantastic creature (dragon head and wings, mermaid tail)

Interior courtyard

[edit]The interior courtyard has a pavement marked with a star that indicates the geographical centre of Brussels. It is decorated with two marble fountains designed in 1714 by Johannes Andreas Anneessens, surmounted by allegorical figures of The Meuse and The Scheldt rivers, sculpted in 1715 by Jean de Kinder and Pierre-Denis Plumier respectively.[28][16]

The north-western and south-eastern façades of the courtyard have two levels pierced by large rectangular windows with wooden mullions with a flat frame and drip edge in the shape of an entablature, all surmounted by a high roof pierced with dormer windows surmounted by a triangular pediment (a structure very similar to the façade on the Rue de l'Amigo/Vruntstraat). On the ground floor, a high door surmounted by a triangular pediment and framed by large lanterns is protected by a large glass awning from the 19th and 20th centuries.[20]

The southern façade is pierced, on the ground floor, with a portal with a basket-handle arch framed by semicircular bays, framed by large lanterns like the other doors of the courtyard. Upstairs, a French window topped with a curved pediment is surrounded by rectangular windows whose flat frames are adorned with crossettes.

-

North-western façade of the inner courtyard

-

Southern façade of the courtyard

-

The Scheldt by Pierre-Denis Plumier (1715)

-

The star that indicates the geographical centre of Brussels

Interior

[edit]Vestibule

[edit]The main rooms are on the first floor. Passing the right entrance, visitors enter the vestibule, also known as the Prince's Gallery. Here are portraits of the princes and governors who ruled the Southern Netherlands from 1695 and of the Kings of the Belgians. There is also a group portrait of the intendants of the Willebroek Canal, with a view of Klein Willebroek.

States of Brabant Room

[edit]In the long rear wing is the States of Brabant Room, built in the early 18th century for the States of Brabant and then used by the Brussels City Council. The lavish decoration is the work of the painter Victor Honoré Janssens. He made the ceiling painting with an Assembly of the Gods and also the cartons for three Brussels tapestries with scenes from the history of Brabant. The three paintings between the windows show female figures against a golden background, representing the cities of Antwerp, Brussels and Leuven. The wooden benches are arranged in a U-shape.

Maximilian Room

[edit]The Maximilian Room next door is named after a 19th-century double portrait of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor and Mary of Burgundy. The space was intended for the administrators of the States of Brabant and was taken over by the College of Mayors and Aldermen. The walls are covered with four tapestries from the eight-part series Life of Clovis, after cartons by the French painter Charles Poerson. The other four tapestries decorate the next room. The Grangé Gallery on the side of the courtyard connects all these rooms. It contains 18th-century portraits of monarchs painted around 1718 by Louis Grangé.

Mayor's cabinet

[edit]The mayor's cabinet is located on the side of the Rue Charles Buls/Karel Bulsstraat. The Waiting Room, originally built for the secretariat of the States of Brabant, is decorated with paintings by Jean-Baptiste Van Moer. They are incorporated into the oak panelling and show the part of Brussels that was destined for demolition because of the covering of the Senne.

Staircase of honour

[edit]The staircase of honour is the result of a late 19th-century renovation to provide direct and monumental access to the mayor's cabinet and the Gothic Room. The original chapel had to make way for this. Paintings by Jacques de Lalaing have been applied to the walls and ceilings. Busts of the mayors are lined up along the landing.

Gothic Room

[edit]The Gothic Room in the oldest part of the Town Hall is in fact neo-Gothic. The wooden cladding is the work of Victor Jamaer. Tapestries from the Mechelen studio Braquenié, designed by Willem Geets, have been incorporated into the long sides. They represent the Guilds of Brussels. The two tapestries on the short side relate to the weapons' guilds. Originally, this was the room in which supreme justice was spoken. The long wall opposite Rue Charles Buls was decorated with The Justice of Trajan and Herkinbald, the famous justice panels of Rogier van der Weyden that were lost in the 1695 bombardment.

Wedding Room

[edit]The Wedding Room has been set up on the side of the Grand-Place. Here too, in the past, justice was spoken and a neo-Gothic transformation has been carried out. A Middle Dutch poem has been reproduced on the roof beams, which, as early as the 15th century, recalled the way to properly govern the city. The corbels show the coats of arms of the Seven Noble Houses of Brussels, and the ceiling those of the guilds.

-

States of Brabant Room

-

Maximilian Room

-

Staircase of honour

-

Gothic Room

-

Wedding Room

Influence

[edit]Brussels' Town Hall was an exemplary work for architects representing the Gothic Revival in the era of historicism. The Austrian architect Friedrich von Schmidt drew inspiration from it when building the City Hall in Vienna. Georg von Hauberrisser, while building the New Town Hall of Munich, also used the building's Brabantian pattern as an architectural example.

-

Brussels' Town Hall was also used as an example for the New Town Hall of Munich.

See also

[edit]- Belfry of Brussels

- History of Brussels

- Culture of Belgium

- Belgium in the long nineteenth century

- List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ State 2004, p. 187.

- ^ a b State 2004, p. 147.

- ^ Staff writer (2011). "Museum of Brussels City (Musée de la Ville de Bruxelles)". Museums. Brussels.info. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- ^ a b "La Grand-Place, Brussels". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ "Ligne 95 vers GRAND-PLACE - STIB Mobile". m.stib.be. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hennaut 2000, p. 5–9.

- ^ a b c d Mardaga 1993, p. 126.

- ^ a b De Vries 2003, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Heymans 2011, p. 10.

- ^ De Vries 2003, p. 30.

- ^ a b Hennaut 2000, p. 20–21.

- ^ De Vries 2003, p. 34.

- ^ State 2004, p. 338–339.

- ^ Mardaga 1993, p. 120.

- ^ Culot et al. 1992.

- ^ a b c Hennaut 2000, p. 32–33.

- ^ a b c Hennaut 2000, p. 37–43.

- ^ a b c Mardaga 1993, p. 128.

- ^ Crick-Kuntziger 1944.

- ^ a b Mardaga 1993, p. 134.

- ^ a b Hennaut 2000, p. 32–33, 37–43.

- ^ a b "Occupation of Brussels on 20 August 1914". City of Brussels. City of Brussels. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ^ "Bruxelles Pentagone - Hôtel de ville - Grand-Place 8". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Des Marez 1918, p. 16.

- ^ Mardaga 1993, p. 128–133.

- ^ Hennaut 2000, p. 44–45.

- ^ a b Mardaga 1993, p. 130.

- ^ Mardaga 1993, p. 133.

Bibliography

[edit]- Crick-Kuntziger, Marthe (1944). Les tapisseries de l'Hôtel de Ville de Bruxelles (in French). Antwerp: De Sikkel.

- Culot, Maurice; Hennaut, Eric; Demanet, Marie; Mierop, Caroline (1992). Le bombardement de Bruxelles par Louis XIV et la reconstruction qui s'ensuivit, 1695–1700 (in French). Brussels: AAM éditions. ISBN 978-2-87143-079-7.

- De Vries, André (2003). Brussels: A Cultural and Literary History. Oxford: Signal Books. ISBN 978-1-902669-46-5.

- Des Marez, Guillaume (1918). Guide illustré de Bruxelles (in French). Vol. 1. Brussels: Touring Club Royal de Belgique.

- Hennaut, Eric (2000). La Grand-Place de Bruxelles. Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Heymans, Vincent (2011). Les maisons de la Grand-Place de Bruxelles (in French). Brussels: CFC Éditions. ISBN 978-2-930018-89-8.

- State, Paul F. (2004). Historical dictionary of Brussels. Historical dictionaries of cities of the world. Vol. 14. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5075-0.

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1B: Pentagone E-M. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1993.

External links

[edit] Media related to Brussels town hall at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Brussels town hall at Wikimedia Commons- Brussels Town Hall - trabel.com

- City Hall in Brussels City - Belgiumview

- Guided tours in the City Hall of Brussels - brussels.be

![The legend of Herkenbald [nl]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/H%C3%B4tel_de_ville_de_Bruxelles_-_Chapiteau_13.JPG/404px-H%C3%B4tel_de_ville_de_Bruxelles_-_Chapiteau_13.JPG)