But I'm a Cheerleader

| But I'm a Cheerleader | |

|---|---|

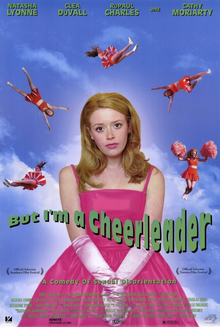

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jamie Babbit |

| Screenplay by | Brian Wayne Peterson |

| Story by | Jamie Babbit |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jules Labarthe |

| Edited by | Cecily Rhett |

| Music by | Pat Irwin |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Lions Gate Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million |

| Box office | $2.6 million[1] |

But I'm a Cheerleader is a 1999 American satirical teen romantic comedy film directed by Jamie Babbit in her feature directorial debut and written by Brian Wayne Peterson.[2] Natasha Lyonne stars as Megan Bloomfield, a high school cheerleader whose parents send her to a residential in-patient conversion therapy camp to "cure" her lesbianism. At camp, Megan realizes that she is indeed a lesbian and, despite the "therapy", comes to embrace her sexuality. The supporting cast includes Clea DuVall, RuPaul, and Cathy Moriarty.

Inspired by an article about conversion therapy and her childhood familiarity with rehabilitation programs, Babbitt used the story of a young woman finding her sexual identity to explore the social construction of gender roles and heteronormativity. The costume and set design of the film highlighted these themes by using artificial textures in intense blues and pinks.

When it was initially rated as NC-17 by the MPAA, Babbit made cuts to allow it to be re-rated as R. When interviewed in the documentary film This Film Is Not Yet Rated, she criticized the MPAA for discriminating against films with homosexual content. While the film has developed a cult following since its release, it was not well received by conservative critics of the time, who compared it unfavorably to the films of John Waters and criticized the colorful production design. The lead actors were praised for their performances but some of the characters were described as stereotypical.

Plot

[edit]Seventeen-year-old high school senior Megan Bloomfield loves cheerleading and is dating Jared, a football player, but does not enjoy kissing him, instead preferring to look at her fellow cheerleaders. This, combined with her interests in vegetarianism and Melissa Etheridge, leads her parents, Peter and Nancy, and friends to suspect that she is a lesbian. Aided by ex-gay Mike, they surprise her with an intervention. She is then sent to True Directions, a two-month-long conversion therapy camp intended to convert attendees to heterosexuality via a five-step program in which they admit their homosexuality, rediscover their gender identity by performing stereotypically gender-associated tasks, find the root of their homosexuality, demystify the opposite sex, and simulate heterosexual intercourse. Upon arrival, she meets strict disciplinarian Mary J. Brown, the program's director. Mary's son Rock is seen throughout the film making multiple sexual overtures towards Mike and the other male campers.

During the program, Megan befriends college student Graham Eaton. Although Graham is more comfortable in her sexuality, she was forced to attend the camp or risk being disowned by her family after her stepmother caught her having sex. Megan meets several other adolescents and young adults trying to cure themselves of their homosexuality. The group's prompting forces her to reluctantly admit her lesbianism, which contradicts her traditional religious upbringing and distresses her, so she puts every effort into becoming heterosexual. Early on in her stay, she shockingly discovers retail worker Clayton Dunn making out with a fellow male camper and varsity wrestler named Dolph. After Mike catches them in the act, Dolph is dismissed from the premises and Clayton is punished with isolation and is sent to a doghouse for a week.

Two of Mary's former students, ex-ex-gays Larry and Lloyd Morgan-Gordon, encourage the campers to rebel against her by taking them to a local gay bar called Cocksucker, where Graham and Megan's relationship becomes romantic. Upon discovering what they did, Mary forces all of them to picket the couple's house, carrying placards and shouting homophobic abuse. Megan and Graham sneak away one night to have sex and begin to fall in love. When Mary discovers their escapade, Megan, now unapologetically comfortable with her sexuality, is dismissed from the premises. Graham, afraid that her continued defiance will result in her father potentially disinheriting her permanently, stays behind.

Disowned by her parents and homeless, Megan goes to stay with Larry and Lloyd, discovering that Dolph now also lives with them. The pair plan to rescue Graham and Clayton by infiltrating the graduation ceremony. While Dolph successfully coaxes Clayton away, Graham initially declines Megan's invitation to join them. Megan then performs a cheer she composed for Graham declaring her love for her, finally winning her over, and they drive off with Dolph and Clayton. The final scene shows Peter and Nancy uncomfortably attending a PFLAG meeting to come to terms with their daughter's homosexuality.

Cast

[edit]- Natasha Lyonne as Megan Bloomfield

- Clea DuVall as Graham Eaton

- Cathy Moriarty as Mary Brown

- RuPaul Charles as Mike

- Mink Stole as Nancy Bloomfield

- Bud Cort as Peter Bloomfield

- Eddie Cibrian as Rock Brown

- Melanie Lynskey as Hilary Vandermueller

- Wesley Mann as Lloyd Morgan-Gordon

- Richard Moll as Larry Morgan-Gordon

- Joel Michaely as Joel Goldberg

- Kip Pardue as Clayton Dunn

- Dante Basco as Dolph

- Douglas Spain as Andre

- Katrina Phillips as Jan

- Katharine Towne as Sinead Lauren

- Brandt Wille as Jared

- Michelle Williams as Kimberly

- Julie Delpy as Lipstick Lesbian

Production

[edit]Background

[edit]But I'm a Cheerleader was Babbit's first feature film,[3] following two short films, Frog Crossing (1996) and Sleeping Beauties (1999). Babbit and producer Andrea Sperling secured financing from Michael Burns, vice president of Prudential Insurance, after showing him the script at Sundance festival.[3][4] Their one-sentence pitch was "Two high-school girls fall in love at a reparative therapy camp."[5] Burns gave an initial budget of US$500,000 which was increased to US$1 million when the film went into production.[4]

Conception

[edit]Babbit, whose mother runs a halfway house called New Directions for young people with drug and alcohol problems, had wanted to make a comedy about rehabilitation and the 12-step program.[5] After reading an article about a man who had returned from a reparative therapy camp hating himself, she decided to combine the two ideas.[4] With girlfriend Sperling, she came up with the idea for a feature film about a cheerleader who attends reparative therapy.[6] They wanted the main character to be a cheerleader because it is ... "the pinnacle of the American dream, and the American dream of femininity."[7] She wanted the film to represent the lesbian experience from the femme perspective, contrasting with several films of the time that represented the butch perspective (Go Fish and The Watermelon Woman).[4] She also wanted to satirize both the religious right and the gay community.[6] Not feeling qualified to write the script herself, Babbit brought in screenwriter and recent graduate of USC School of Cinematic Arts Brian Wayne Peterson.[6][7] Peterson had experience with reparative therapy while working at a prison clinic for sex offenders.[5] He has said that he wanted to make a film that would not only entertain people, but also anger them and encourage them to talk about the issues it raised.[5]

Casting

[edit]Babbit recruited Clea DuVall, who had starred in her short film Sleeping Beauties, to play the role of Graham Eaton. She met much of the cast through DuVall, including Natasha Lyonne and Melanie Lynskey.[3] Lyonne first saw the script in the back of DuVall's car and contacted her agent about it;[5] having seen and enjoyed Sleeping Beauties, she was eager to work with her.[8] Lyonne was not the first choice for the role of Megan. Another actress had wanted to play the part but eventually turned it down due to her religious beliefs and not wanting her family to see her on the poster.[3] Rosario Dawson was also considered for Megan, but her executive producer persuaded her that Dawson, who is Hispanic, would not be right for the All-American character.[6]

A conscious effort was made to cast people of color in supporting roles to combat what Babbit described as "racism at every level of making movies."[6] From the beginning, she intended the characters of Mike (played by RuPaul), Dolph (Dante Basco) and Andre (Douglas Spain) to be African American, Asian and Hispanic, respectively. She initially considered Arsenio Hall for the character of Mike but Hall was uncomfortable playing a gay role.[7] As Mike, RuPaul made a rare appearance out of drag.[9]

Set and costume design

[edit]Babbit says that her influences for the look and feel of the film included John Waters, David LaChapelle, Edward Scissorhands and Barbie.[6] She wanted the production and costume design to reflect the themes of the story. The progression from the ordinary world of Megan's home life, where the dominant colors are muted oranges and browns, to the contrived world of True Directions with intense blues and pinks, is intended to represent the artificiality of heteronormativity.[6] The germaphobic character of Mary Brown represents AIDS paranoia; her clean, ordered world is filled with plastic flowers, fake sky and PVC outfits.[6] The external shots of the colorful house complete with bright pink agricultural fencing were filmed in Palmdale, California.[5]

Themes

[edit]

But I'm a Cheerleader contains themes of sexuality, gender roles and social conformity. Chris Holmlund in Contemporary American Independent Film notes this feature of the film and calls the costumes "gender-tuned".[10] Ted Gideonse in Out magazine wrote "the costumes and colors of the film show how false the goals of True Directions are".[5] The film provides a positive representation of LGBTQ community by casting a diverse range of characters who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender. This film has become a classic within the LGBTQ community as it helps raise awareness of the harms of conversion therapy.[11]

Rating and distribution

[edit]When originally submitted to the Motion Picture Association of America rating board, But I'm a Cheerleader received an NC-17 rating. In order to get a commercially viable R rating, Babbit removed a two-second shot of Graham's hand sweeping Megan's clothed body, a camera pan of Megan's body when she is masturbating, and a comment that Megan "ate Graham out".[12]

Babbit was interviewed by Kirby Dick for his 2006 documentary film This Film Is Not Yet Rated. The film argues that films with homosexual content are treated more stringently than those with only heterosexual content, and that scenes of female sexuality draw harsher criticism from the board than those of male sexuality. Babbit stated that she felt discriminated against for making a gay film.[13] The film was rated as M (for mature audiences 15 and older) in Australia and in New Zealand, 14A in Canada, 12 in Germany and 15 in the United Kingdom.

The film premiered on September 12, 1999, at the Toronto International Film Festival and was screened in January 2000 at the Sundance Film Festival. It was shown at other international film festivals including the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras festival and the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival.[14]

Following its Toronto premiere, Fine Line Features acquired North American distribution rights to the film for "low six figures", committing $500,000 to prints and advertisement and promising its filmmakers gross participation.[15] However, the deal fell through in February 2000 over doubts regarding home video rights, with Lions Gate Films acquiring North American rights the following month and releasing it theatrically in the United States on July 7, 2000.[16][14] The film was first released to home video by Universal Studios on October 3, 2000, and by Lions Gate on July 22, 2002.[17] In honor of the film's 20th anniversary, the director's cut of But I'm a Cheerleader was released via video on demand on December 8, 2020,[18] and on Blu-ray on June 1, 2021.[19]

Reception

[edit]Box office and audience reaction

[edit]But I'm a Cheerleader grossed $2,595,216 worldwide. In its opening weekend, showing at four theaters, it earned $60,410 which was 2.7% of its total gross.[14] According to Box Office Mojo, it ranked at 174 for all films released in the US in 2000 and 74 for R-rated films released that year.[14] The film was a hit with festival audiences and received standing ovations at the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival.[20] It has been described as a favorite with gay audiences and on the art house circuit.[21]

Critical response

[edit]At the time of its initial release But I'm a Cheerleader polarized critics. On Rotten Tomatoes, it has an approval rating of 42% from 90 reviews, with the site's critical consensus stating, "Too broad to make any real statements, But I'm a Cheerleader isn't as sharp as it should be, but a charming cast and surprisingly emotional center may bring enough pep for viewers looking for a light social satire."[22] On Metacritic, it has a weighted average score of 39 out of 100 based on 30 critics, indicating "generally unfavorable reviews".[23] Elvis Mitchell of The New York Times praised Lyonne and DuVall for their performances.[24] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times described the movie as having "jaunty, superficial humor" that "tends more to confirm homosexual stereotypes for easy laughter than to skewer the horror of [conversion therapy]".[25] Emanuel Levy of Variety described it as a "shallow, only mildly entertaining satire".[26] Roger Ebert said "It feels like an amateur night version of itself, awkward, heartfelt and sweet".[27]

Reviews from gay media were positive, and the film has undergone a critical reassessment over time. AfterEllen.com named it "one of the five best lesbian movies ever made";[28] the site had considered the movie's story "predictable" and characters "stereotypical" in its initial 2006 review.[29] Curve called the film an "incredible comedy" that "redefined lesbian film."[30]

Awards

[edit]The film won the Audience Award and the Graine de Cinéphage Award at the 2000 Créteil International Women's Film Festival.[31] It was nominated by the Political Film Society of America for the PFS Award in the categories of Human Rights and Exposé the same year.

Music

[edit]Pat Irwin composed the score for But I'm a Cheerleader. The soundtrack has never been released on CD. Artists featured include Saint Etienne, Dressy Bessy, April March and RuPaul.

Track listing

- "Chick Habit (Laisse tomber les filles)" (Elinor Blake, Serge Gainsbourg) performed by April March

- "Just Like Henry" (Tammy Ealom, John Hill, Rob Greene, Darren Albert) performed by Dressy Bessy

- "If You Should Try and Kiss Her" (Ealom, Hill, Greene, Albert) performed by Dressy Bessy

- "Trailer Song" (Courtney Holt, Joy Ray) performed by Sissy Bar

- "All or Nothing" (Cris Owen, Miisa) performed by Miisa

- "We're in the City" (Sarah Cracknell, Bob Stanley, Pete Wiggs) performed by Saint Etienne

- "The Swisher" (Dave Moss, Ian Rich) performed by Summer's Eve

- "Funnel of Love" (Kent Westbury, Charlie McCoy) performed by Wanda Jackson

- "Ray of Sunshine" (Go Sailor) performed by Go Sailor

- "Glass Vase Cello Case" (Madigan Shive, Jen Wood) performed by Tattle Tale

- "Party Train" (RuPaul) performed by RuPaul

- "Evening in Paris" (Lois Maffeo) performed by Lois Maffeo

- "Together Forever in Love" (Go Sailor) performed by Go Sailor

Legacy

[edit]The music video for the 2021 song "Silk Chiffon" by musical group Muna with Phoebe Bridgers pays homage to But I'm a Cheerleader and features much of the film's iconography. Guitarist Naomi McPherson said they wanted "a song for kids to have their first gay kiss to."[32]

Musical

[edit]In 2005, the New York Musical Theatre Festival featured a musical stage adaptation of But I'm a Cheerleader written by lyricist Bill Augustin and composer Andrew Abrams. With 18 original songs, it was directed by Daniel Goldstein and starred Chandra Lee Schwartz as Megan. It played during September 2005 at New York's Theatre at St. Clement's. The musical was also performed as part of MT Fest UK from February 18 to 20, 2019 at The Other Palace in London, with a cast featuring Bronté Barbé as Megan, Carrie Hope Fletcher as Graham, Jamie Muscato as Jared, Matt Henry as Mike, Ben Forster as Larry, Stephen Hogan as Lloyd and Luke Bayer as Clayton.

A production of the musical played at the Turbine Theatre in London, beginning previews February 18, 2022. It opened on February 23 and ran until April 16. It was directed by Tania Azevedo, choreographed by Alexzandra Sarmiento, and produced by Paul Taylor-Mills and Bill Kenwright in association with Adam Bialow, with lighting by Martha Godfrey.[33] The musical returned to the Turbine Theatre later that year, running from October 7 to November 27.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "But I'm a Cheerleader (1999)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 17, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Babbit, Jamie (August 11, 2000), But I'm a Cheerleader (Comedy, Drama, Romance), Natasha Lyonne, Clea DuVall, Michelle Williams, Cheerleader LLC, Hate Kills Man (HKM), Ignite Entertainment, archived from the original on September 20, 2023, retrieved September 23, 2023

- ^ a b c d "Interview with Jamie Babbit". AfterEllen. February 7, 2012. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2004). "Jamie Babbit". In Duchovnay, Gerald (ed.). Film Voices: Interviews from Post Script. SUNY Press. pp. 153–165. ISBN 0-7914-6156-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gideonse, Ted (2000). "The New Girls Of Summer". Out: 54–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "So Many Battles to Fight Interview with Jamie Babbit". nitrateonline.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c Grady, Pam (March 6, 2005). "Rah Rah Rah: Director Jamie Babbit and Company Root for But I'm a Cheerleader". Archived from the original on March 6, 2005. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Judd, Daniel (September 27, 2007). "Jamie Babbit". Rainbow Network. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "Ladies' Man: An Interview with Superdiva RuPaul". October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Holmlund, Chris (2004). "Generation Q's ABCs: Queer Kids and 1990s' Independent Films". In Holmlund, Chris; Wyatt, Justin (eds.). Contemporary American Independent Film: From the Margins to the Mainstream. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25486-8.

- ^ Martin,, Syd (2018). [Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol8/iss1/1 Archived April 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine ""But I'm a Cheerleader: Queer in Content and Production," Cinesthesia: Vol. 8: Iss. 1,"]. Article 1

- ^ Taubin, A. (August 3, 1999). "Erasure Police". The Village Voice. p. 57.

- ^ "'This Film is Not Yet Rated' Explores Anti-Gay Bias of MPAA Ratings System". GayWired.com. October 17, 2007. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "But I'm a Cheerleader". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 2, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Jones, Oliver (September 17, 1999). "Fine Line cheering pix at Toronto". Variety. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ Harris, Dana (March 6, 2000). "Lions Gate pacts for 'Cheerleader'". Variety. Retrieved November 23, 2024.

- ^ "But I'm a Cheerleader DVD". MovieWeb. September 25, 2012. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Rubin, Rebecca (December 4, 2020). "'But I'm a Cheerleader' Director Jamie Babbit on the Queer Classic 20 Years Later: 'I Wanted to Make a Gay 'Clueless". Variety. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "But I'm a Cheerleader Blu-ray (Director's Cut)". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ "New York Lesbian And Gay Film Festival". Filmfestivals.com. March 25, 2012. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Benshoff, Harry; Griffin, Sean (2004). America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22583-8.

- ^ "But I'm a Cheerleader". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 19, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- ^ "But I'm a Cheerleader Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 8, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (July 7, 2000). "Don't Worry. Pink Outfits Will Straighten Her Out". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (July 21, 2000). "'But I'm a Cheerleader' Works Against Its Goals". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel (September 23, 1999). "But I'm a Cheerleader". Variety. Archived from the original on August 31, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "But I'm A Cheerleader movie review (2000) | Roger Ebert". Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ^ "Sapphic Cinema: "But I'm a Cheerleader"". AfterEllen. September 25, 2015. Archived from the original on January 11, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

- ^ "Review of "But I'm a Cheerleader"". AfterEllen. January 18, 2012. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "Women to Watch in Film". Curve. November 2003. p. 22.

- ^ Sullivan, Moira. "MMI Movie Review: But I'm a Cheerleader-- Jamie Babbit Wins Créteil Films de Femmes 'Prix du Public'". Movie Magazine International. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ Curto, Justin (September 7, 2021). "Let's Go, Lesbians! The Muna and Phoebe Bridgers Collab Is Here". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ^ Meyer, Dan (November 30, 2021). "But I'm A Cheerleader: The Musical Will Get London Premiere in 2022". Playbill. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ Putnam, Leah (September 14, 2022). "But I'm a Cheerleader: The Musical Will Return to London's Turbine Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

External links

[edit]- 1999 films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s coming-of-age comedy films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s satirical films

- 1990s teen comedy films

- 1990s teen romance films

- 1999 directorial debut films

- 1999 independent films

- 1999 LGBTQ-related films

- 1999 romantic comedy films

- American coming-of-age comedy films

- American independent films

- American romantic comedy films

- American satirical films

- American teen LGBTQ-related films

- American teen romance films

- Cheerleading films

- Coming-of-age romance films

- English-language romantic comedy films

- English-language independent films

- Films about anti-LGBTQ sentiment

- Films about conversion therapy

- Films about interracial romance

- Films about sexual repression

- Films adapted into plays

- Films directed by Jamie Babbit

- Films produced by Andrea Sperling

- Films shot in Los Angeles County, California

- Gay-related films

- The Kushner-Locke Company films

- Lesbian-related films

- LGBTQ-related coming-of-age comedy films

- LGBTQ-related controversies in film

- LGBTQ-related independent films

- LGBTQ-related romantic comedy films

- LGBTQ-related satirical films

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Rating controversies in film

- Vegetarianism in fiction