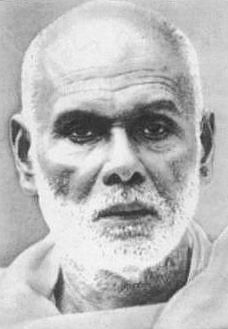

Chempakaraman Pillai

Chempakaraman Pillai | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 September 1891 |

| Died | 26 May 1934 (aged 42) |

| Other names | Champak |

| Organization(s) | Berlin Committee, Provisional Government of India |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement, Indo-German Conspiracy |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Reformation in Kerala |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Notable people |

|

| Others |

Chempakaraman Pillai (alias Venkidi;[1] 15 September 1891 – 26 May 1934) was an Indian-born political activist and revolutionary.[2] Born in Thiruvananthapuram, to Tamil parents, he left for Europe as a youth, where he spent the rest of his active life as an Indian nationalist and revolutionary.[3]

Although his life was mired in controversies, including a squabble with Adolf Hitler,[4] information on his life in Europe was sketchy in the immediate years after his death. More information has come out in recent years.[1]

Chempakaraman Pillai is credited with the coining of the salutation and slogan "Jai Hind"[1][5] in the pre-independence days of India. The slogan is still widely used in India.

Pillai, who started the Indian National Voluntary Corps on 31 July 1914, was instrumental in inspiring Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose to start the Indian National Army (INA).[4]

Early life

[edit]Pillai was born into a Tamil Vellalar family in Thiruvananthapuram, capital of the erstwhile Kingdom of Travancore in the modern state of Kerala. His parents, Chinnaswami Pillai and Nagammal, hailed from Nanjinad (in present-day Kanyakumari district, Tamil Nadu).[2]

In Europe

[edit]Pillai attended ETH Zurich from October 1910 until 1914, pursuing a diploma in Engineering. After the outbreak of the First World War, he founded the International Pro-India Committee and based its headquarters in Zürich, appointing himself president in September 1914. During the same period an Indian Independence Committee was formed in Berlin by a group of Indian expatriates in Germany. This latter group was composed of Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, Bhupendranath Dutta, A. Raman Pillai, Taraknath Das, Maulavi Barkatullah, Chandrakant Chakravarty, M. Prabhakar, Birendra Sarkar, and Heramba Lal Gupta.[citation needed]

In October 1914, Pillai moved to Berlin and joined the Berlin Committee, merging it with his International Pro-India Committee as the guiding and controlling institution for all pro-Indian revolutionary activities in Europe. Lala Har Dayal was also persuaded to join the movement. Both of them cooperated with the German Intelligence Bureau for the East and helped creating German propaganda directed at Indian PoWs in German camps, particularly the Halbmondlager.[6] Soon branches sprang up in Amsterdam, Stockholm, and Washington, as well as in many other parts of Europe and the Americas.[citation needed]

SMS Emden bombing of British Madras

[edit]On 22 September 1914, The SMS Emden, a German warship commanded by Captain Karl von Muller entered the waters off the coast of Madras, and bombed the facilities near the Madras harbour and slipped back into the ocean. The British were taken aback in this sudden attack. His family stated that Pillai coordinated the German attack with his personal presence in the SMS Emden, though this is not the official view. In any case, it is widely believed that Pillai and some Indian revolutionaries had a hand in the SMS Emden bombing of Madras.[2][1]

War activities

[edit]Indian Independence Committee ultimately became involved in the Hindu–German Conspiracy along with the Ghadar Party in the United States. The German foreign office under Kaiser Wilhelm II funded the Committee's anti-British activities. Chempakaraman and A. Raman Pillai, both from Travancore and both students at German universities, worked together on the Committee. Pillai later allied with Indian National Army chief Subhas Chandra Bose.

Many of Pillai's letters to A. Raman Pillai, then a student in the University of Göttingen, were kept by Raman Pillai's son Rosscote Krishna Pillai. The letters reveal some aspects of Pillai's life in Germany between 1914 and 1920, as does one of July 1914, calling upon Indian soldiers in the British Indian Army to rise in revolt and fight against the British.

After the end of World War I and Germany's defeat, Pillai stayed in Germany, working as a technician in a factory in Berlin; when Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose visited Vienna, Pillai met him and explained his plan of action.[7]

Foreign Minister of Provisional Government of India

[edit]

Pillai was the foreign minister of the Provisional Government of India set up in Kabul, Afghanistan on 1 December 1915, with Raja Mahendra Pratap as President and Maulana Barkatullah as Prime Minister. However, the defeat of the Germans in the war shattered the hopes of the revolutionaries, and the British forced them out of Afghanistan in 1919.

During this time, the Germans were helping the Indian revolutionaries from their own motives. Though the Indians made it clear to the Germans that they were equal partners in their fight against the common enemy, the Germans wanted to use the revolutionaries' propaganda work and military intelligence for their own purposes.[6]

In 1907, Pillai coined the term "Jai Hind",[8][9][10] which was adopted as a slogan of the Indian National Army in the 1940s at the suggestion of Abid Hasan.[11] After India's independence, it emerged as a national slogan.[12]

Marriage and death

[edit]In 1931, Pillai married Lakshmi Bai of Manipur, whom he had met in Berlin. Unfortunately they had a short life together, as Pillai soon fell ill. There were symptoms of slow poisoning and he went to Italy for treatment.

Pillai died in Berlin on 28 May 1934. Lakshmibai brought his ashes to British India in 1935 where they were later ceremonially immersed in Kanyakumari with full state honours.[13] It was Pillai's final wish that his ashes be sprinkled in Nanjinad (Kanyakumari), his family's native place.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Indugopan, G.R. (27 September 2016). "Chempaka Raman Pillai: The freedom fighter who coined 'Jai Hind'". Onmanorama. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d Krishnan, Sairam (17 August 2016). "Did a Tamil man from Trivandrum mastermind the bombing of British Madras during World War I?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Mathew, K. M.; Mammen, Matthew (2009). Malayala Manorama Yearbook (in Tamil). Kottayam: Malayala Manorama Co. p. 301. ISBN 978-8-189-00412-5.

- ^ a b "Chempaka Raman Pillai: The freedom fighter who coined 'Jai Hind'".

- ^ Encyclopaedia of South Indian Culture and Heritage. New Bharatiya Book Corporation. 2021. p. 24. ISBN 978-93-5521-768-4. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ a b Liebau, Heike (2019). ""Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen": Das Berliner Indische Unabhängigkeitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914–1920)". MIDA Archival Reflexicon: 2–4.

- ^ Encyclopaedia of South Indian Culture and Heritage. New Bharatiya Book Corporation. 2021. p. 24. ISBN 978-93-5521-768-4. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Charles Stephenson (2009). Germany's Asia-Pacific Empire: Colonialism and Naval Policy, 1885-1914. Boydell Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-84383-518-9.

...Champakaraman Pillai, a committed anti-imperialist. He is credited with coining the phrase 'Jai Hind' meaning 'Victory for India'...

- ^ Saroja Sundararajan (1997). Madras Presidency in pre-Gandhian era: a historical perspective, 1884-1915. Lalitha Publications. p. 535.

To Champakaraman Pillai goes the credit of coining the taraka mantra "Jai Hind" in 1907...

- ^ Encyclopaedia of South Indian Culture and Heritage. New Bharatiya Book Corporation. 2021. p. 24. ISBN 978-93-5521-768-4. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

- ^ Gurbachan Singh Mangat (1986). The Tiger Strikes: An Unwritten Chapter of Netaji's Life History. Gagan Publishers. p. 95.

- ^ Sumantra Bose (2018). Secular States, Religious Politics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-108-47203-6.

- ^ Rose, N. Daniel (4 December 2007). "A Forgotten Fighter". The New Indian Express. Chennai. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

External links

[edit]- Asghar Ali Engineer (2006). They Too Fought for India's Freedom: The Role of Minorities. Hope India Publications. ISBN 81-7871-091-9. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

- Heike Liebau: "„Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen“: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängigkeitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914–1920)." In: MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019), ISSN 2628-5029, 1–11.