Vilnius Cathedral

| Cathedral Basilica of St Stanislaus and St Ladislaus | |

|---|---|

Lithuanian: Vilniaus Šv. Stanislovo ir Šv. Vladislovo arkikatedra bazilika | |

| |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| 54°41′09″N 25°17′16″E / 54.68583°N 25.28778°E | |

| Location | Vilnius |

| Country | Lithuania |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Cathedral-Basilica |

| Founder(s) | Original: King Mindaugas Current: Ignacy Jakub Massalski |

| Dedication | St Stanislaus and St Ladislaus |

| Consecrated | 1783 |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) | Laurynas Gucevičius |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Gothic, Baroque, Neoclassical |

| Groundbreaking | Original: 1251 Current: 1779 |

| Completed | 1783 |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | plastered masonry |

| Administration | |

| Archdiocese | Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Vilnius |

| Official name | Vilnius Old Town |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii), (iv) |

| Designated | 1994 |

| Reference no. | 541 |

| UNESCO region | Europe |

The Cathedral Basilica of St Stanislaus and St Ladislaus of Vilnius (also known as Vilnius Cathedral; Lithuanian: Vilniaus Šv. Stanislovo ir Šv. Vladislovo arkikatedra bazilika; Polish: Bazylika archikatedralna św. Stanisława Biskupa i św. Władysława, historical: Kościół Katedralny św. Stanisława[1]) is the main Catholic cathedral in Lithuania.[2] It is situated in Vilnius Old Town, just off Cathedral Square.[2] Dedicated to the Christian saints Stanislaus and Ladislaus, the church is the heart of Catholic spiritual life in Lithuania.[2]

The cathedral was previously used for the inauguration ceremonies of Lithuanian monarchs with Gediminas' Cap, while in modern times it is a venue for masses dedicated to the elected Presidents of Lithuania after their inauguration ceremonies and giving of oaths to the Nation in the Seimas Palace.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

History

[edit]

It is believed that in pre-Christian times, the Baltic pagan god Perkūnas was worshipped at the site of the cathedral. It has also been postulated that the Lithuanian King Mindaugas ordered the construction of the original cathedral in 1251 after his conversion to Christianity and appointment of a bishop to Lithuania. Remains of the archaic quadratic church with three naves and massive buttresses have been discovered underneath the current structure in the late 20th century.[8] After Mindaugas's death in 1263, the first cathedral again became a place of pagan worship.

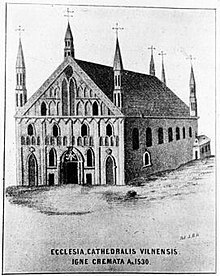

In 1387, the year in which Lithuania was officially converted to Christianity, construction began on a second Gothic cathedral with five chapels. This second cathedral, however, burnt down in 1419. During preparations for his 1429 coronation as King of Lithuania, Vytautas built a significantly larger Gothic cathedral in its place. Although the coronation never took place, the walls and pillars of this third cathedral have survived to this day. The third cathedral had three naves and four circular towers at its corners, and Flemish traveler Guillebert de Lannoy noticed its similarity to the Frauenburg cathedral. In 1522, the cathedral was renovated, and a bell tower was built on top of the Lower Castle defensive tower. After another fire in 1530, it was rebuilt again and between 1534 and 1557 more chapels and the crypts were added. The cathedral acquired architectural features associated with the Renaissance.

The coronations of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania took place within its confines. Inside its crypts and catacombs are buried many famous people from Lithuanian and Polish history including Vytautas (1430), his wife Anna (1418), his brother Sigismund (Žygimantas) (1440), his cousin Švitrigaila (1452), Saint Casimir (1484), Alexander Jagiellon (1506), and two wives of Sigismund II Augustus: Elisabeth of Austria (1545) and Barbara Radziwiłł (1551). The heart of the Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania Władysław IV Vasa was buried there upon his death, although the rest of his body is buried at the Wawel Cathedral in Kraków.

In 1529, the Crown Prince and future King of Poland, Sigismund II Augustus, was crowned Grand Duke of Lithuania in the cathedral. During the inaugurations of Lithuanian monarchs until 1569, Gediminas' Cap was placed on the monarch's head by the Bishop of Vilnius in Vilnius Cathedral.[3] The demand of a separate inauguration ceremony of the Grand Duke of Lithuania was raised by the nobles of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (e.g. Mikołaj "the Red" Radziwiłł, Eustachy Wołłowicz, Jan Karol Chodkiewicz, Konstanty Ostrogski) during the negotiations of the Union of Lublin, however it was not officially included into it and the rulers of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth were since then elected in the Election sejms.[9][10] Nevertheless, on 29 May 1580, bishop Merkelis Giedraitis in the Vilnius Cathedral presented Grand Duke Stephen Báthory (King of Poland since 1 May 1576) a luxuriously decorated sword and a hat adorned with pearls (both were sanctified by Pope Gregory XIII himself), while this ceremony manifested the sovereignty of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and had the meaning of elevation of the new Grand Duke of Lithuania, this way ignoring the stipulations of the Union of Lublin.[11][12][13][14]

After yet another fire in 1610, the cathedral was rebuilt again, and the two front towers were added. The cathedral was damaged again in 1655 when Vilnius fell to Russian troops in the Russo-Polish War of 1654–1667. It was renovated and redecorated several more times.

Between 1623 and 1636, at the initiative of Sigismund III Vasa and later completed by his son Wladyslaw IV Vasa, the Baroque style Saint Casimir chapel by royal architect Costante Tencalla was built of Swedish sandstone. Its interior was reconstructed in 1691–1692 and decorated with frescoes by Michelangelo Palloni, the altar and stuccowork by Pietro Perti. This chapel contains sculpted statutes of Jagiellon kings and an epitaph with Wladyslaw IV Vasa's heart. More than anything in the Cathedral this chapel symbolizes the glory of Polish-Lithuanian union and common history.

In 1769 the southern tower, built during the reconstruction of 1666 collapsed, destroying the vaults of the neighbouring chapel and killing 6 people. After the damage, Bishop of Vilnius Ignacy Jakub Massalski ordered the reconstruction of the cathedral. The works started in 1779 and were completed in 1783, and the interior was completed in 1801. The cathedral was reconstructed to its present appearance according to the design of Laurynas Gucevičius in the Neoclassical style; the church acquired a strict quadrangular shape common to local public buildings. The main facade was adorned with sculptures of the Four Evangelists by Italian sculptor Tommaso Righi. Some scholars point to the architectural resemblance of the cathedral to the works of Andrea Palladio or see the influence of Gucevičius's tutor Claude Nicolas Ledoux.[15] The influence of Palladian architecture is evident in side facades of the building. The lack of 'purity' of the Classical architecture, due to incorporation of Baroque style sculptures and other elements, was later criticized by academical architects, notably Karol Podczaszyński.

Between 1786 and 1792 three sculptures by Kazimierz Jelski were placed on roof of the Cathedral - Saint Casimir on the south side, Saint Stanislaus on the north, and Saint Helena in the centre. These sculptures were removed in 1950 and restored (sculptor Stanislovas Kuzma) in 1997.[16][clarification needed] Presumably the sculpture of St. Casimir originally symbolized Lithuania, that of St. Stanislaus symbolized Poland, and that of St. Helena holding a 9 m-golden cross represents the true cross.[citation needed]

During the Soviet occupation, the cathedral was converted into a warehouse. Masses were celebrated again starting in 1988, although the cathedral was still officially called The Gallery of Images at that time. In 1989, its status as a cathedral was restored. In January that year, the remains of Albertas Goštautas were discovered in the cathedral wall.[17]

In 2002 work officially began to rebuild the Royal Palace of Lithuania behind the cathedral. The newly erected palace building considerably altered the context of the cathedral.

The cathedral and the belfry were thoroughly renovated from 2006 to 2008. The facades were covered with fresh multicolor paintwork, greatly enhancing the external appearance of the buildings. It was the first renovation since the restoration of Lithuania's independence in 1990.

In 2018, the cathedral’s tympanum and several of its plinths were repaired. In 2022, the roof was renovated after part of its was blown off by strong winds. In 2023, the roof lantern above St Casimir’s Chapel and the sacristy were repaired.[18]

Architecture

[edit]Inside, there are more than forty works of art dating from the 16th through 19th centuries, including frescoes and paintings of various sizes. During the restoration of the cathedral, the altars of a presumed pagan temple and the original floor, laid during the reign of King Mindaugas, were uncovered. In addition, the remains of the cathedral built in 1387 were also located. A fresco dating from the end of the 14th century, the oldest known fresco in Lithuania, was found on the wall of one of the cathedral's underground chapels.

Gallery

[edit]-

The fresco in the Vilnius Cathedral, dating to the Christianization of Lithuania

-

Façade of Vilnius Cathedral in a 1847 drawing

-

The Bell Tower

-

Litas coin to commemorate Vilnius Cathedral

-

Side view of Vilnius Cathedral

-

Façade view of the Vilnius Cathedral at night

-

Statue of apostle Mark

-

Statue of apostle Matthew

-

Statue of apostle Luke

-

Statue of Moses

-

Cartouche on the wall of St. Casimir's Chapel in Vilnius. West wall of Vilnius Cathedral

-

Bas-relief of Vilnius Cathedral

References

[edit]- ^ Kirkor, Adam Honory (1880). Przewodnik po Wilnie i jego okolicach (2nd ed.). Nakładem i drukiem Józefa Zawadzkiego. pp. 72, 102.

- ^ a b c d "Vilniaus katedra ir varpinė". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b Gudavičius, Edvardas. "Gedimino kepurė". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- ^ "LR Prezidentės Dalios Grybauskaitės inauguracija. Prezidentūros rūmų perdavimo ceremonija". Lithuanian National Radio and Television (in Lithuanian). 1 January 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Nausėdos inauguracijos ceremonija: nauji simboliniai žingsniai, tvirta kalba Seime ir žaismingas bendravimas su žmonėmis". Lithuanian National Radio and Television (in Lithuanian). 12 July 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ Samoškaitė, Eglė. "Brazausko iškilmės be žmonos, 4 Adamkaus pokyliai ir ponių stilius: štai kuo per inauguraciją stebino Nausėdos pirmtakai". TV3.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ "Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidento įstatymas". Official website of Seimas. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ Mindaugas's Cathedral according to archaeological data

- ^ Jasas, Rimantas. "Liublino unija". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Tyla, Antanas. "Elekcinis seimas". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ "Vavelio pilies lobyne – ir Lietuvos, Valdovų rūmų istorija". Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Bues, Almut (2005). "The year-book of Lithuanian history" (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Lithuanian Institute of History: 9. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Stryjkowski, Maciej (1846). Kronika polska, litewska, żmódzka i wszystkiéj Rusi Macieja Stryjkowskiego. T. 2 (in Polish). Warsaw. p. 432. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Ragauskienė, Raimonda; Ragauskas, Aivas; Bulla, Noémi Erzsébet (2018). Tolimos bet artimos: Lietuvos ir Vengrijos istoriniai ryšiai (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius. p. 67. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ [1] Archived 27 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Vilniaus arkikatedra". Ldmuziejus.mch.mii.lt. 27 March 2006. Archived from the original on 7 January 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ^ Jankauskas, Rimantas. "LDK istorija: Vilniaus vaivados ir LDK kanclerio Alberto Goštauto kūno antropologinis tyrimas". 15min.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ Narkunas, Vilius. "Vilnius Cathedral needs renovation, but who should pay?". LRT. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- Roman Catholic churches completed in 1783

- 18th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in Lithuania

- Roman Catholic cathedrals in Lithuania

- Basilica churches in Lithuania

- Rebuilt buildings and structures in Lithuania

- Roman Catholic churches in Vilnius

- Burial sites of the Gediminids

- Burial sites of the Jagiellonian dynasty

- Burial sites of the House of Radziwiłł

- Burial sites of the House of Vasa

- Objects listed in Lithuanian Registry of Cultural Property

- Neoclassical church buildings in Lithuania

- Landmarks in Vilnius