Provisional Government of Oregon

Provisional Government of Oregon | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1841/1843–1849 | |||||||||

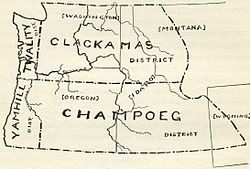

Original districts of the government with the eventual U.S. borders and states superimposed | |||||||||

| Status | Part of the United States (1846–1849) | ||||||||

| Capital | Oregon City | ||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||

| Executive | |||||||||

• 1841–1843 | Supreme Judge Ira Babcock | ||||||||

• 1842–1843 | Chairman of the Committee at Champoeg Meetings Ira Babcock | ||||||||

• 1843–1845 | Executive Committee | ||||||||

• 1845–1849 | Governor George Abernethy | ||||||||

| Legislature | Unicameral | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Appointment of constitutional committee and election of Supreme Judge at Champoeg | February 18, 1841 | ||||||||

• First Wolf Meeting at Champoeg | February 1, 1843 | ||||||||

• Second Wolf Meeting at Champoeg | March 6, 1843 | ||||||||

• Creation of the Provisional Government at Champoeg | May 2, 1843 | ||||||||

| March 3, 1849 | |||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||

| |||||||||

The Provisional Government of Oregon was a popularly elected settler government created in the Oregon Country (1818-1846), in the Pacific Northwest region of the western portion of the continent of North America. Its formation had been advanced at the Champoeg Meetings since February 17, 1841, and it existed from May 2, 1843 until March 3, 1849, and provided a legal system and a common defense amongst the mostly American pioneers settling an area then inhabited by the many Indigenous Nations. Much of the region's geography and many of the Natives were not known by people of European descent until several exploratory tours and expeditions were authorized at the turn of the 18th to the 19th centuries, such as Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery going northwest in 1804-1806, and United States Army Lt. Zebulon Pike and his party first journeying north, then later to the far southwest.

The Organic Laws of Oregon were adopted in 1843 with its preamble stating that settlers only agreed to the laws "until such time as the United States of America extend their jurisdiction over us".[3] According to a message from the government in 1844, the rising settler population was beginning to flourish among the "savages", who were "the chief obstruction to the entrance of civilization" in a land of "ignorance and idolatry".[3]

The provisional government had organized with the traditional three branches that included a legislature, judiciary, and executive branch. The executive government was at first the Executive Committee, consisting of three members, in effect from 1843 to 1845; then in 1845, a governor replaced the committee. The judicial branch had a single Supreme Judge along with several lower local courts, and a legislative committee of nine served temporarily as a legislature until later when the lower chamber of the Oregon House of Representatives for the new federal Oregon Territory was established in August 1848 by action of the United States Congress and approved by the President up to statehood in 1859.

Background

[edit]A series of frontiersmen and pioneer colonists assemblies were held over several years across the recently settled Willamette Valley, of the Oregon Country, with many on the French Prairie at Champoeg. On February 9, 1841, the death of prominent early settler Ewing Young (1799-1841), – who left no last will and testament nor had any heirs in Oregon Country region – left the future of his property uncertain.[4] On February 17, missionary Jason Lee (1803-1845), chaired the first meeting organised to discuss the matter. He proposed the creation of an authority over the pioneers centered on a governor.[5] Some French-Canadian settlers blocked the measure and instead a probate judge and a few other positions were appointed.[6]

Further attempts at a pioneer government floundered until increased numbers of wagon train caravans traveling westward over the Oregon Trail led to an increase in the American settler population from the east.[4] Initiated by William H. Gray (1810-1889), the "Wolf Meetings" of early 1843 created a bounty system on animal predators attacking settlers' livestock of cattle, pigs and sheep.[6] Further discussions began among the settlers until a gathering was finally held at Champoeg on May 2, with under 150 Americans and French-Canadians participating.[7] The proposal for forming a provisional government was tabled and voted on twice.[4] The first vote rejected the presented report due to the inclusion of a governor, with a second vote on each individual text item / provision that was proposed.[8] Two months later, on July 5, 1843, the Organic Laws of Oregon, modeled after the 1838 Iowa Territory's Organic Law and the previous old Ordinance of 1787 (adopted 56 years before by the former Confederation Congress (1781-1789), under the earlier governing document of the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union drawn up 1776-1780, and adopted 1781, for establishing the old Northwest Territory (1787-1803) north of the Ohio River and around the Great Lakes), were adopted by the new American and former French-Canadian colonists of the Willamette Valley, establishing the Provisional Government of Oregon.[6]

The government was, according to pioneers Overton Johnson and William H. Winter (1819-1879), intended from the start as an interim entity, until "whenever [the United States] extends her jurisdiction over the Territory".[9] (Johnson would go on to serve as Recorder for the provisional government for a few months in 1844.)

Structure

[edit]The Organic Laws were drafted by a legislative committee on May 16, 1843 and June 28, 1843, before being adopted on July 5.[10] Although not a formal constitution, the document outlined the laws of the government.[10] Two years later, on July 2, 1845, a new set of Organic Laws was drafted to revise and clarify the previous version; this newer version was adopted by a majority vote of the people on July 26, 1845.[10] This constitution-like document divided the government into three departments: a judiciary branch, an executive branch, and a legislature.[10] The definition of the executive branch had previously been modified, in late 1844, from a three-person committee to a single governor; this change took effect in 1845.[4]

When appealing for military aid from the American Government in the aftermath of the Whitman massacre, the settlers detailed the structural weaknesses of the Provisional Government:

The very nature of our compact formed between the citizens of a republic and the subjects and official representatives of a monarchy, is such that the ties of political union could not be drawn so closely as to produce that stability and strength sufficient to form an efficient government. This union between democrats of a republic and wealthy aristocratic subjects of a monarchy could not be formed without reserving to themselves the right of allegiance to their respective governments. Political jealousy and strong party feeling have tended to thwart and render impotent the acts of a government, from its very nature weak and insufficient.[11]

Executive branch

[edit]

With the first set of laws, the people created a three-person Executive Committee to act as an executive.[6] The Second Executive Committee was elected on May 14, 1844, and served until June 12, 1845.[4] A December 1844 amendment of the Organic Laws eliminated the Executive Committee in favor of a single governor, taking effect in June 1845.[4] At that time George Abernethy was elected as the first governor.[3] Abernethy would be the only governor under the Provisional Government. He was reelected in 1847, and served until 1849.[10]

Legislative branch

[edit]

The Provisional Legislature held session mainly in Oregon City.[12] They met at different times each year, and in 1848 they did not meet; too many members had left for the California gold fields.[13] The legislature enacted various laws, sent memorials to Congress, incorporated towns and organizations, and granted divorces and licenses to run ferries.[3][12][13] After the establishment of the Oregon Territory, the legislature was replaced with the two house Oregon Territorial Legislature.

Judicial branch

[edit]

The Provisional Government also included a judiciary. The forerunner of the Oregon Supreme Court consisted of a single Supreme Judge and two justices of the peace.[14] The Supreme Judge was elected by the people, but the legislature could select someone as presiding judge as a replacement if needed.[15] This Supreme Court had original and appellate jurisdiction over legal matters, whereas the lower probate court and justice courts that were also created could only hear original jurisdictional matters when the amount in controversy was less than $50 and did not involve land disputes.[14] Some judges under the Provisional Government were Nathaniel Ford, Peter H. Burnett, Osborne Russell, Ira L. Babcock, and future United States Senator James W. Nesmith.[15]

Districts

[edit]During its existence the Provisional Government's authority was restricted to the pioneer settlements, generally located in or around the Willamette Valley.[3][7][16] The entire Oregon Country was decreed to be covered by four administrative divisions.[6] Initially created on July 5, 1843, were the Twality, Yamhill, Clackamas and Champooick (later Champoeg) districts.[6] Yamhill district claimed the lands west of the Willamette River and a line extending from its course, and south of the Yamhill River.[6] Champooick District was adjacent to the east, its northern border the confluence of the Pudding and Molalla Rivers.[6] Twality District was directly north of Yamhill District, its eastern border extending from the mouth of the Willamette River.[6] Clackamas District was to contain "all the territory" that was not decreed a part of the other three districts, located east of Twality District and north of Champooick District.[6] The extent of land claimed north was vague, being "south of the northern boundary of the United States".[6] Despite this the government was defined to extend over all the lands east to the Rocky Mountains and north of the Mexican territory of Alta California.[6][16]

Throughout 1843 and 1844, no attempts were made at controlling lands north of the Columbia River, then under the influence of the Hudson's Bay Company through Fort Vancouver.[17][18] In June 1844 the Columbia River was declared as the northern border of the Provisional Government, but by December the most expansive American claim in the Oregon boundary dispute of Parallel 54°40′ north was adopted.[19] On December 22, 1845 districts were renamed to counties.[10] Additional districts were created over time from the original four, including the Clatsop, Vancouver, Linn, Clark, Polk, Benton counties.[6][19]

Other

[edit]Other government positions included Recorder, Treasurer, Attorney, and Sheriff.[3] The recorder position would later become the position of Secretary of State.

Laws

[edit]

With the formation of the Provisional Government, a committee of nine individuals were elected to frame the laws of the government.[14] This Legislative Committee consisted of David Hill, Robert Shortess, Alanson Beers, William H. Gray, James A. O'Neil, Robert Newell, Thomas J. Hubbard, William Dougherty, and Robert Moore who was elected as the chairman of the committee.[14] Each member was to be paid $1.25 per day for their services with the first meeting held May 15, 1843.[14] On July 4 a new gathering began at Champoeg with speeches for and against the proposals of the committee.[14] Then on July 5, 1843 the Organic Laws of Oregon are adopted by popular vote after being recommended by the Legislative Committee, with the laws modeled after Iowa's Organic Law and the Ordinance of 1787, creating the de facto first Oregon constitution.[20] Scholars and historians have appraised the First Organic Laws as being "very crude and unsatisfactory",[17] not allowing for an effective government body to function.[21][16][22]

Over the course of nearly six years under the provisional government, the settlers passed numerous laws. One law allowed people to claim 640 acres (2.6 km2) if they improved the land, which would be solidified later by Congress' adoption of the Donation Land Claim Act.[12] Another law allowed the government to organize a militia and call them out by order of the Executive or Legislature.[3] Under the first Organic Laws of 1843 inhabitants were guaranteed due process of law and a right to a trial by jury.[6] Some other rights established were: no cruel and unusual punishment, no unreasonable bails for defendants, and no takings of property without compensation.[6]

Following the Cockstock Incident in 1844, the legislature decreed that African Americans could not reside in the Oregon Country, only David Hill and Asa Lovejoy voting against the bill.[4][6] The punishment for any freemen was to be administered every six months of their residency being "not less than twenty nor more than thirty-nine stripes".[3] The law was never actually enforced and was struck down in July 1845. However, in 1849 the legislature passed a new law once again prohibiting African Americans in the territory, but differed from the original 1844 law in that it applied to African Americans entering after it was passed, and it used different means to enforce it.[23][24] Despite facing legal discrimination that denied them suffrage and threatened violence, black pioneers remained in Oregon. While the USS Shark was in the region in 1846, its commanding officer estimated there were around 30 black settlers.[25]

In 1844, the legislature passed a law banning the sale of ardent spirits, out of concern that the Native Americans would become hostile if intoxicated.

Finances

[edit]Prior to the creation of the Provisional Government, the economic activities by in the Oregon European descendants Country were focused on the fur trade. A system called "wheat credit" was established in the 1830s for French-Canadian settlers on the French Prairie.[26] The farmers would take their harvests to a granary in Champoeg, where a receipt for its market value was given,[26] valid for use at HBC stores.[27] Another item used for transactions by French-Canadian and later American pioneers were beaver skins.[1]

The first Organic Laws only authorised voluntary donations, a measure deemed a "utopian scheme", and provided scant funds.[28] A tax on real estate and personal property was created in 1844,[10] that covered a third of that year's expenses.[7] The next year the property tax was doubled to .0025% and a 50¢ poll tax was levied as well, with failure to pay resulting in disenfranchisement.[10] Sheriffs acted as tax collectors,[19] but their position was made difficult due to the poverty or unwillingness of many colonists to pay what was owed.[10] Taxes were paid in wheat and gathered at appointed locations for the district, largely HBC warehouses.[19]

A small amount of silver coins from Peru and Mexico freely circulated as legal tender.[1] Minor financial agreements were completed in lieu of currency with assorted agricultural products, such as "wheat, hides, tallow, beef, pork, butter, lard, peas, lumber and other articles of export of the territory" [2] One pioneer recalled the lack of currency, receiving at most 25¢ in transactions between 1844 and 1848.[29] To overcome the lack of circulating coins, Abernethy gathered scraps of flint left over from arrowhead production by local indigenous.[30] After attaching scraps of paper to them, the amount owed by Abernethy was written on one and given to customers, transferable for other supplies at his store.[30] Coins remained a prized item by settlers for example, during a sale of lots in Oregon City a property manager offered a discount of 50% if paid in specie.[31]

A traveler who visited Oregon before the arrival of American merchants reported that HBC stores sold goods at rates lower than in the United States.[32] As merchants from the United States became established in the region, they chaffed under the economic hegemony of the HBC. The vendors pressed for the HBC to charge more for sales to pioneers, which the company did for two years, only for American customers.[33] Joel Palmer reported that without the British company "the prices would be double what they are now".[33]

The small American merchant class and officers of the HBC loaned settlers more credit than most could refund.[34] Fears of creditors demanding restitution from the farmers lead to wheat receipts and scrips issued by the government declared valid currency in 1845.[34][35][36] The law decreeing wheat as currency was ridiculed for not establishing financial standards for the merchants, who were de facto bankers.[37] Between 1847 and 1848 the local market for wheat became flooded from overproduction, causing a decline in its value.[26] The legislature repealed previous regulations on December 20, 1847, making only gold, silver and treasury drafts on valid currency.[19] Thus, the creditors of the territory were able to protect their financial standing by removing wheat as tender.[26]

Around $8,000 from the poll and property taxes were collected over the course of the government, far short of the expenses amounting to $23,000.[10]

California

[edit]After the Conquest of California during the ongoing Mexican–American War, American settlers began to move to the newly seized land. This created a demand for Oregonian wheat; proceeds from the sale of barrels of flour amounted to $10 per keg in 1847.[38] The start of the Gold Rush caused an immense rise in demand for various products in Californian markets. Economic transactions with the pioneer settlements of Oregon increased greatly, with the number of visiting vessels in 1849 was triple that of the previous eight years.[26] Between 1848 and 1851 Oregon lumber and wheat sent to the new markets fetched rates two to three times higher than in 1847.[26] Significant amounts of gold dust began to circulate in the Willamette Valley, though impurities were common.[3] The Oregon Exchange Company was authorized by the legislature to begin producing Beaver Coins in early 1849,[39] though production began on March 10, a week after the dissolution of the Provisional Government.[2]

Settlement with the Hudson's Bay Company

[edit]The mounting debts of the government, though it could "scarcely hope" to force the HBC company posts to adhere to its authority, made establishing an agreement with the HBC a priority.[18] An employee of the company, Francis Ermatinger, was elected to the position of Treasurer in July after carrying the French-Canadian vote.[3] In August Applegate inquired to Chief Factor John McLoughlin if the HBC would pay taxes and join the Provisional Government.[40] At the same time a member of the legislature, David Hill, tabled a bill on August 15 that would deny any HBC employees citizenship or suffrage.[6] The measure failed to pass, but demonstrated the feelings of the "Ultra-Americans" towards the company.[40]

While Applegate and McLoughlin held a conference, plans for the administration of the territory above the Columbia River, to be named Vancouver, were begun.[40] The Chief Factor found the Provisional Government a satisfactory way to pursue the debts owed to the HBC by settlers, and protect company property against claim jumpers.[40] Additionally he felt if the government were to openly declare independence from outside powers he could "be elected head were I to retire among them".[18] The negotiations ended with the condition that only sales with settlers would be taxed.[40] Taxes paid to the Provisional Government by the HBC and the Puget Sound Agricultural Company amounted to $226 that year.[40] Several more employees of the HBC were then included in the government. Chief Trader James Douglas was appointed as a justice for Vancouver after the signing of the agreement and in 1846 he and fellow employee Henry Newsham Peers were elected to the legislature.[1][18] If there were any sessions of the Vancouver court, none of the records or correspondence remain.[1] Claims were filed by British subjects covering the HBC forts of Vancouver, Cowlitz, and Nisqually.[40] Vancouver in particular was covered by 18 claims.[25]

British reaction to the agreement was generally negative. It was seen as unneeded by William Peel, son of Prime Minister Peel, who arrived with small flotilla several days after its signing.[41] Mervin Vavasour was in the Oregon Country gathering intelligence about the defensive capabilities of the HBC posts and voiced the minority view that the compact was to the benefit of "peace and prosperity of the community at large".[42]

Militia

[edit]The organic laws laid out plans for a militia of a battalion of mounted riflemen commanded by an officer with the rank of major, with annual inspections.[6] Every male settler between 16 and 60 who wanted to be "considered a citizen" had to be a part of the military; failure to do so would incur fines.[6] (This remains so under modern Oregon law, though now both sexes are included, and the age range is only 18 to 45.)[43] Under the first Organic Laws, power to call out the militia was vested in the Executive Committee, though any officer of the militia could also call them out in times of insurrection or invasion.[6]

Cayuse War

[edit]In December 1847, after learning of the Whitman Massacre from HBC Chief Factor James Douglas, Governor Abernethy and the legislature met to discuss the situation.[12] Major Henry A. G. Lee was placed in charge of a company called the Oregon Rifles on December 8 and was ordered to The Dalles. At that location the force established Fort Lee on December 21.[10][44] An additional force of 500 men was to meet in Oregon City by December 25.[12] This group prosecuted the war east of the Cascades under the command of Cornelius Gilliam.[4]

The war continued until five Cayuse emissaries, which according to Archbishop François Norbert Blanchet, were sent to "have a talk with the whites and explain all about the murderers, ten in number, who were no more, and had been killed by the whites, the Cayuses and were all dead."[45] However, the Cayuse party was imprisoned and transported to Oregon City. When the group was asked why they offered themselves to the militia, Tiloukaikt stated "Did not your missionaries teach us that Christ died to save his people? So die we to save our people."[7] At a military court Tiloukait and the four other Cayuses, Tomahas, Klokamas, Isaiachalkis, and Kimasumpkinhese, were found guilty and hanged on June 3, 1850, at Oregon City.[4]

Subsequent history

[edit]Signed on June 15, 1846, the Oregon Treaty ended the dispute between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the United States, by dividing the Oregon Country at the 49th parallel.[7] This extended U.S. sovereignty over the region, but effective control would not occur until government officials arrived from the United States. Two years later, on August 14, 1848, the United States Congress created the Oregon Territory; this territory included today's states of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming.[7] Appointed Governor of the Oregon Territory by President Polk, Joseph Lane arrived at Oregon City on March 2, 1849.[12]

Governor Lane kept the legal code of the dissolved provisional government, apart from immediately repealing the law authorizing the minting of the Beaver Coins, as this was incompatible with the United States Constitution (Article I, Section 8).[7] The creation of the Washington Territory in 1854 removed the northern half of the Oregon Territory.[46] Established on February 14, 1859, the State of Oregon was composed of roughly the western half of the territory, the remaining eastern section being added to the Washington Territory.[46]

- U.S. states created in whole or in part from the Oregon Territory

See also

[edit]- Columbia District

- Historic regions of the United States

- Judges of the Provisional Government

- History of Oregon

- History of Washington

- History of Idaho

- History of Montana

- History of Wyoming

- Methodist Mission

- Oregon pioneer history

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Scott, Leslie M. "Pioneer Gold Money, 1849". Oregon Historical Quarterly 33, No. 1 (1932), pp. 25-30

- ^ a b c Strevey, T. Elmer. "The Oregon Mint". The Washington Historical Quarterly 15, No. 4 (1924), pp. 276–284

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brown, J. Henry (1892). Brown's Political History of Oregon: Provisional Government. Portland: Wiley B. Allen. LCCN rc01000356. OCLC 422191413.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Horner, John B. Oregon: Her History, Her Great Men, Her Literature. Portland: The J.K. Gill Co. 1919

- ^ Grover, La Fayette, The Oregon Archives Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine, Salem: A. Bush, 1853

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t The Organic Act in Grover, Lafayette. The Oregon Archives. Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine Salem: A. Bush. 1853, pp. 26-35

- ^ a b c d e f g Bancroft, Hubert and Frances Fuller Victor. History of Oregon. Archived 2015-01-31 at the Wayback Machine Vol. 1. San Francisco: History Co., 1890.

- ^ Loewenberg, Robert J. "Creating a Provisional Government in Oregon: A Revision". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 68, No. 1 (1977), pp. 20-22

- ^ Johnson, Overton; Winter, William H. (1846). . as reproduced in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, 1906.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Corning, Howard M. Dictionary of Oregon History. Binfords & Mort Publishing, 1956.

- ^ Memorial of Legislative Assembly of Oregon Territory relative to their present situation and wants. Archived 2016-05-20 at the Wayback Machine in Miscellaneous Documents Printed by Order of the House of Representatives, during the First Session of the Thirtieth Congress... Vol. 1. Washington: Tippin & Streeper, 1848. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f Clarke, S. A. Pioneer Days of Oregon History, Volume 2. Portland, Oregon: J. K. Gill Co. 1905

- ^ a b "Beginnings of Self-Government". The End of the Oregon Trail Interpretive Center. Archived from the original on February 10, 2007. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f

Gray, William H. (1870). A History of Oregon, 1792-1849, Drawn from personal observation and authentic information. Portland: Harris & Holman.

- ^ a b "Oregon Supreme Court Justices". Oregon Blue Book. Oregon Secretary of State. Archived from the original on July 6, 2018. Retrieved March 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c

Clark, Robert C. (June 1912). "How British and American Subjects Unite in a Common Government for Oregon Territory in 1844". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 13 (2): 140–159. JSTOR 20609901.

- ^ a b

Holman, Frederick V. (1912). "A brief history of the Oregon Provisional Government and what caused its formation". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 13 (2): 89–139.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Robert C. "Last Step in Provisional Government". Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 16, No. 4 (1915), pp. 313–329

- ^ a b c d e Oregon Territorial Government. Laws of a General and Local Nature passed by the Legislative Committee and Legislative Assembly. Archived 2016-07-01 at the Wayback Machine Salem, Oregon: Asahel Bush. 1853.

- ^ Dobbs, Caroline C. (1932). Men of Champoeg: A Record of the Lives of the Pioneers Who Founded the Oregon Government. Metropolitan Press.

- ^ Bancroft, Hubert Howe; Victor, Frances Fuller (1886). History of Oregon Vols.1-2. San Francisco, California: History Company. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

- ^

Bradley, Mari M. (1908). "Political Beginnings in Oregon. The Period of the Provisional Government, 1839–1849". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 9 (1): 42–72. JSTOR 20609761.

- ^ Mcclintock, Thomas C. (January 1, 1995). "James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Black Exclusion Law of June 1844". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 86 (3): 121–130. JSTOR 40491550.

- ^ Mcclintock, Thomas C. "James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Black Exclusion Law of June 1844". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86, No. 3 (1995), pp. 121–130

- ^ a b Neil M. Howison. Oregon: Report of Lieut. Neil M. Howison, United States Navy, to the Commander of the Pacific Squadron. Archived 2016-05-28 at the Wayback Machine Washington D.C.: Tippin & Streppen. 1848

- ^ a b c d e f Gilbert, James Henry. Trade and Currency in Early Oregon. New York City: MacMillan Co. 1907

- ^ Lyman, H. S. "Reminiscences of F. X. Matthieu". Archived 2016-03-14 at the Wayback Machine Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 1, No. 1 (1900), p. 102

- ^ Shippee, Lester B. "The Federal Relations of Oregon—VII". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 20, No. 4 (1919), pp. 345-395

- ^ Oregon Pioneer Association. Transactions of the Twenty-Third Annual Reunion. Archived 2016-05-21 at the Wayback Machine Portland: George H. Himes and Co. 1895, p. 109

- ^ a b Oregon Native Son and Historical Magazine, Vol. 1. Archived 2016-04-28 at the Wayback Machine Portland: Native Son Publishing Co. 1899, p. 90

- ^ "Farm for sale". Oregon Spectator.Archived 2015-11-24 at the Wayback Machine, January 21, 1847, p. 3

- ^ Sage, Rufus B. Scenes in the Rocky Mountains. Archived 2016-06-09 at the Wayback Machine Philadelphia: Carey & Hart. 1846, p. 223

- ^ a b Palmer, Joel and Reuben Gold Thwaites. Palmer's Journal of Travels over the Rocky Mountains, 1845-1846. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Co. 1906, pp. 217–218

- ^ a b "The Currency". Oregon Spectator. Archived 2015-11-24 at the Wayback Machine, May 14, 1846, p. 2

- ^ Oregon Acts and Laws. Archived 2016-04-29 at the Wayback Machine New York City: N. A. Phemister Co.

- ^ Gray, William H. A History of Oregon, 1972–1849. Portland: Harris & Holman. 1870, p. 437

- ^ "Repeal the Currency Law". Oregon Spectator. Archived 2015-11-24 at the Wayback Machine, November 25, 1847, p. 2

- ^ "Letter from C. E. Picket of California..." Oregon Spectator. Archived 2015-11-24 at the Wayback Machine, June 10, 1847, p. 2

- ^ Carey, Charles H. History of Oregon. Portland: Pioneer Historical Publishing Co. 1922. p. 407

- ^ a b c d e f g Judson, Katharine B. "Dr. John McLoughlin's Last Letter to the Hudson's Bay Company, as Chief Factor, in charge at Fort Vancouver, 1845". Archived 2017-01-04 at the Wayback Machine The American Historical Review 21, No. 1 (1915), pp. 104–134

- ^ Scott, Leslie M. "Report of Lieutenant Peel on Oregon in 1845–46". Oregon Historical Quarterly 29, No. 1 (1928), pp. 51–76

- ^ Schafer, Joseph. "Documents Relative to Warre and Vavasour's Military Reconnoissance in Oregon, 1845-6". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 10, No. 1 (1909), pp. 1-99

- ^ Oregon Revised Statutes 10§396 Archived 2016-03-26 at the Wayback Machine. Published by the Legislative Counsel Committee of the Oregon Legislative Assembly. 2005. Retrieved on July 20, 2007.

- ^ Fagan, David D. 1885. History of Benton County, Oregon: including its geology, topography, Oregon: D. D. Fagan.

- ^ Blanchet, François N. Historical Sketches of the Catholic Church in Oregon. Portland: 1878. pp. 182–184

- ^ a b Evans, Elwood. Washington Territory: Her Past, Her Present, and the Elements of Wealth which Ensure Her Future. Archived 2016-05-02 at the Wayback Machine Olympia, Washington: C. B. Bagley. 1877. pp. 15–17

Further reading

[edit]- Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of Oregon: Volume 1, 1834-1848. San Francisco, CA: The History Company, 1886.

- J. Henry Brown, Brown's Political History of Oregon: Provisional Government: Treaties, Conventions, and Diplomatic Correspondence on the Boundary Question; Historical Introduction of the Explorations on the Pacific Coast; History of the Provisional Government from Year to Year, with Election Returns and Official Reports; History of the Cayuse War, with Original Documents. Portland, OR: Wiley B. Allen, 1892.

- John T. Condon, "The Oregon Laws of 1845," Washington Historical Quarterly, vol. 12, no. 4 (Oct. 1921), pp. 279–282. In JSTOR

- George H. Himes, "Organizers of the First Government in Oregon," Washington Historical Quarterly, vol. 6, no. 3 (July 1915), pp. 162–167. In JSTOR

- Frederick V. Holman, "A Brief History of the Oregon Provisional Government and What Caused Its Formation," Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, vol. 13, no. 2 (June 1912), pp. 89–139. In JSTOR (Free)

- Mirth Tufts Kaplan, "Courts, Counselors and Cases: The Judiciary of Oregon's Provisional Government," Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 62, no. 2 (June 1961), pp. 117–163. In JSTOR

- Robert J. Loewenberg, "Creating a Provisional Government in Oregon: A Revision," Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 1 (Jan. 1977), pp. 13–24. In JSTOR

- Kent D. Richards, "The Methodists and the Formation of the Oregon Provisional Government," Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 2 (April 1970), pp. 87–93. In JSTOR

- H. W. Scott, "The Formation and Administration of the Provisional Government of Oregon," Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society, vol. 2, no. 2 (June 1901), pp. 95–118. In JSTOR (Free)

- Leslie M. Scott, "Oregon's Provisional Government, 1843-49," Oregon Historical Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3 (Sept. 1929), pp. 207–217. In JSTOR

- J. Quinn Thornton, "History of the Provisional Government of Oregon," from Constitution and Quotations from the Register of the Oregon Pioneer Association, Together with the Annual Address of Hon. S.F. Chadwick, Remarks of Gov. L.F. Grover, at Reunion, June 1874, and Other Matters of Interest. Salem, OR: E.M. Waite, 1875; pp. 43–96.

External links

[edit] Media related to Provisional Government of Oregon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Provisional Government of Oregon at Wikimedia Commons- Oregon Secretary of State: Historical County Offices and Duties