Heckler v. Chaney

| Heckler v. Chaney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued December 3, 1984 Decided March 20, 1985 | |

| Full case name | Margaret M. Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services v. Larry Leon Chaney, et al. |

| Citations | 470 U.S. 821 (more) 105 S. Ct. 1649; 84 L. Ed. 2d 714; 1985 U.S. LEXIS 78; 53 U.S.L.W. 4385; 15 ELR 20335 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit |

| Holding | |

| The FDA's decision not to take the enforcement actions requested by respondents was not subject to review under the Administrative Procedure Act. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

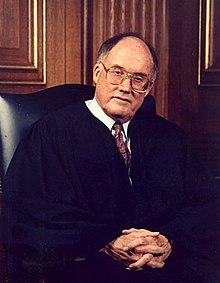

| Majority | Rehnquist, joined by Burger, Brennan, White, Blackmun, Powell, Stevens, O'Connor |

| Concurrence | Brennan |

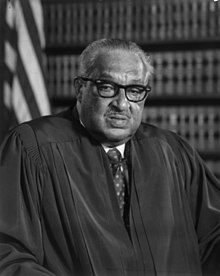

| Concurrence | Marshall (in judgment) |

| Laws applied | |

| Administrative Procedure Act | |

Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821 (1985), is a decision of the Supreme Court of the United States which held that a federal agency's decision to not take an enforcement action is presumptively unreviewable by the courts under section 701(a)(2) of the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The case arose out of a group of death row inmates' petition to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), seeking to have the agency thwart the state governments' plans to execute the inmates by lethal injection. The FDA declined to interfere, a decision the inmates appealed unsuccessfully to the District Court for the District of Columbia. On further review, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals held that the FDA's action was reviewable and that its denial was "arbitrary and capricious". The Supreme Court unanimously reversed the appeals court and declared in an 8–1 decision that agency nonenforcement decisions were presumptively unreviewable.

The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals reacted to Overton Park by holding that practical considerations should be used in determining whether to grant review, rather than looking at the laws relevant to the agency in question – in Chaney, they did precisely this in overturning the district court. The Supreme Court overturned the appeals court's decision and upheld Overton Park's emphasis on statutory considerations, but the presumption of unreviewability it created in this case was largely based on practical factors rather than statutory factors. It reasoned that, in general, an agency's decision not to enforce does not easily lend itself to manageable standards of judicial review, likening such a decision to one a prosecutor might make. It highlighted, however, that the presumption of unreviewability can be rebutted where the plaintiffs provide a relevant statute ("law to apply") that limits the discretion of the agency.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. concurred with the majority and emphasized that the court was not closing off all avenues of review for nonenforcement decisions. Justice Thurgood Marshall concurred in the judgment only, criticizing the majority's decision to create a presumption of unreviewability and instead arguing that the FDA's decision should have been held to be reviewable and upheld on the merits. Lower courts largely accepted the ruling, albeit with varying interpretations of scope; the wider legal community criticized the majority's rationale for a presumption of unreviewability while agreeing with the result immediately concerning the inmates.

Background

[edit]Case

[edit]

| Administrative law of the United States |

|---|

|

Prior to the 1970s, U.S. states primarily executed prisoners with either the electric chair or the gas chamber. Supporters of lethal injection said it was more dignified and less painful than electrocution.[1][2] In 1977, Oklahoma became the first U.S. state to pass a law authorizing execution via lethal injection. A day after Oklahoma passed its statute, Texas passed its own version.[3] By 1984, fifteen states had adopted lethal injection as a method of execution.[1][2]

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund and two people sentenced under these statutes petitioned the FDA asserting that the use of barbiturates and derivatives of curare for executions by untrained personnel "may actually result in agonizingly slow and painful deaths".[4] These petitioners were Larry Leon Chaney of Jenks, Oklahoma, who was convicted of the 1977 murder of Kendal Ashmore, and Doyle Skillern, who was convicted of the 1974 murder of Patrick Randel.[5][6] Chaney was the second person in the state to be sentenced to death by lethal injection; his protracted legal battle in state and federal courts was met with little initial luck, including the U.S. Supreme Court thrice declining to review Chaney's case.[7]

Per the petitioners, their states were planning to use drugs for lethal injection that had not been approved by the FDA for that purpose, in violation of two provisions of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act's (FDCA). First, they contended, their states had violated the FDCA by distributing a "new drug" by way of interstate commerce. While the drugs were FDA-approved, the petitioners argued they were "new drugs" under the statutory requirements because they were not approved by the FDA as "safe and effective" for lethal injections. Second, they said that their states' use of approved drugs for unapproved purposes violated the "misbranding" provisions of the act.[4] They requested that the FDA affix warning labels stating that the drugs were not approved for human execution, notify state corrections officials that the drugs should not be used, seize prison stockpiles and recommend the prosecution of those who knowingly continued to sell the drugs for use in executions.[8][9]

That July, in a letter to the inmates' lawyer, the FDA declined. The head of the FDA wrote that the FDA did not have clear jurisdiction to interfere with state criminal justice systems and was authorized by its "inherent discretion to decline to pursue certain enforcement matters" even if the requested actions were within the scope of the agency's jurisdiction.[10][1]

The inmates appealed the FDA's refusal to the United States District Court for the District of Columbia in Chaney v. Schweiker.[a][10][13] By this time, the number of petitioners had increased to eight. Five of them were from Oklahoma, including Chaney, Alton C. Franks, Carl Morgan, Charles William Davis, and Robyn Leroy Parks; three were from Texas, including Skillern, Jerry Joe Bird, and Henry Martinez Porter.

Administrative Procedure Act

[edit]The Court has held since Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner (1967) that the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) (codified as 5 USC §§ 701-706) provides a "basic presumption of judicial review" that would need "clear and convincing evidence" of legislative intent for an exemption.[14] Despite the presumption of reviewability, actions "committed to agency discretion by law" are unreviewable under §701(a)(2) of the APA.[15] The exception is a narrow one; courts are authorized by §706 of the Act to set aside actions of federal agencies that are "arbitrary, capricious, [or] an abuse of discretion". If all legitimately conferred agency discretion was unreviewable, § 706(a)(2) would have no effect.[9]

The court first directly ruled on § 701(a)(2) in Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe (1971), ruling that it only included cases where "statutes are drawn in such broad terms that in a given case there is no law to apply" to the case.[16] This standard provoked criticism from legal scholars who pointed out that § 706 required judicial review.[17][18] Cass Sunstein noted that when "an agency has taken constitutionally impermissible factors into account, there is always 'law to apply'—no matter what the governing statute may say."[19]

Some lower courts followed this standard to its letter, but others skirted or flouted its terms. Courts in the District of Columbia Circuit in particular argued that the "law to apply" standard allowed weighing policy considerations that were not expressly stated in the statute or legislative history. Some commentators said that the D.C. Circuit was completely disregarding the Supreme Court's decision under the guise of following it.[20][21]

The Supreme Court previously ruled that agency inaction was reviewable in Dunlop v. Bachowski (1975) and that "§§ 702 and 704 subject the Secretary's decision to judicial review under the standard specified in § 706 (2)(A)".[citation needed] The Court dismissed the argument that the secretary's decision was an unreviewable exercise of prosecutorial discretion reasoning that enforcement discretion was limited in the civil context to cases which "like criminal prosecutions, involve the vindication of societal or governmental interests, rather than the protection of individual rights."[22][23] The Court concluded that "[a]lthough the Secretary's decision to bring suit bears some similarity to the decision to commence a criminal prosecution, the principle of absolute prosecutorial discretion is not applicable to the facts of this case".[24] Justice William Rehnquist dissented from the decision, arguing that the secretary's action was an exercise of agency discretion under § 701(a)(2).[25]

Court proceedings

[edit]Lower courts

[edit]

On August 30, 1982, the District Court for the District of Columbia issued a summary judgment holding that the nonenforcement decisions are "essentially unreviewable by the courts". The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, in a divided opinion, reversed the district court. The majority opinion, written by Judge J. Skelly Wright invoked the "strong presumption of reviewability" set out in earlier cases, applying Overton Park's narrow "no law to apply" test to decide if the agency decision was "committed to agency discretion by law". Judge Wright cited an FDA policy statement in which the agency committed itself to "investigate...thoroughly" unapproved uses of new approved drugs that are "widespread or [endanger] the public health".[22][26] Having asserted that the agency's nonenforcement decision was reviewable, Wright ruled the agency had abused its discretion.[27]

Judge Antonin Scalia dissented, arguing that the majority cited Dunlop, Overton Park, and Gardner erroneously and that they did not apply to the case at hand. While he agreed that there is a strong presumption of reviewability towards agency action in general, he argued that agency enforcement decisions carried a strong presumption of nonreviewability, and that the three precedential cases were not intended to address section 701(a)(2) and this case.[28] He also noted that the FDA policy statement was attached to a proposed rule that was never adopted.[29] In a subsequent opinion, Scalia also criticized the court's regular reliance on pragmatic considerations.[30] The Supreme Court's reversal was largely based on the dissent.[31]

Supreme Court

[edit]

The Supreme Court, ruling unanimously against Chaney, held that agency nonenforcement decisions are presumptively unreviewable by the courts. Justice Thurgood Marshall concurred in judgement only, and did not join the majority opinion.[32]

Writing for the majority, William Rehnquist said that enforcement decisions were presumed unreviewable under the § 701(a)(2) "committed to agency discretion" exception to the general presumption of reviewability.[33] The presumption of unreviewability was based on the well-established common law doctrine of prosecutorial discretion. Justice Rehnquist said the decision to bring an enforcement action "has traditionally been 'committed to agency discretion' and we believe that Congress enacting the APA did not intend to alter that tradition".[34] The Court presented four policy considerations to support the presumption of unreviewability:[33]

- An agency's ordering of enforcement priorities involves weighing of complex factors within the agency's expertise.[35]

- An agency's decision to bring an enforcement action is analagous to prosecutorial discretion which "has long been regarded as the special province of the Executive Branch".[36]

- There is no action to provide a focus for judicial review.[37]

- While action may involve the use of an agency's "coercive power", inaction does not infringe upon a person's rights.[38]

The presumption of unreviewability of enforcement decisions is not absolute, and can be overcome if the petitioner can find "law to apply" in the governing statue. Applying Overton Park, the Court said agency actions were within the § 701(a)(2) exception "if the statute is drawn so that a court would have no meaningful standard against which to judge the agency's exercise of discretion."[39][40] The court concluded that judicial review of nonenforcement decisions was permitted where "the substantive statute has provided guidelines for the agency to follow in exercising its...powers."[41] However, the Court said there was often "no law to apply" to review nonenforcement decisions.[33]

Speaking to the presumption of reviewability affirmed in Dunlop that was relied on by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, Justice Rehnquist remarked that "our textual references to the 'strong presumption' of reviewability in ... [Bachowski] were addressed only to the § (a)(1) exception; we were content to rely on the [Third Circuit] Court of Appeals' opinion to hold that the § (a)(2) exception did not apply."[42] Justice Rehnquist said the presumption of unreviewability would have been overcome because the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act "quite clearly [withdrew] discretion from the agency and [provided guidelines] for the exercise of its enforcement power."[43] The Court said the FDCA contained no such constraints because the misbranding and new drug provisions did not limit agency discretion and distinguished Dunlop on this ground.[22]

The court dismissed the FDA policy statement on the same grounds Scalia did: the proposed rule that statement was attached to was never adopted by the agency, and the court additionally found the language to be ambiguous on the matter. The court also refused to interpret a clause of the FDCA exempting the Secretary from exercising authority for minor violations as implying a requirement for action against major violations, reasoning that it could only apply where the agency had already established that a major violation took place, which does not happen if the agency declines to investigate.[22][44]

It also left open the possibility that there could be judicial review under several other circumstances, including where an agency refuses to make a rule, resolves to fully ignore its statutory obligations, or makes a nonenforcement decision that is based solely on jurisdictional grounds or violates a plaintiff's constitutional rights.[45]

Concurring opinions

[edit]

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote a short concurrence contending that section 701(a)(2) was not intended to allow agencies to disregard "clear jurisdictional, regulatory, statutory, or constitutional commands", and instead should restrict challenges to what he asserted were hundreds of daily routine nonenforcement decisions that would otherwise be open to lawsuit. He argued that judicial review should still be available in the areas the majority left open or where an agency's decision stood on "illegitimate reasons", but still concurred with the presumption of unreviewability put forward in this case.[46][47]

Justice Marshall, on the other hand, concurred in the judgement only. He agreed that the FDA was within its discretion to direct its resources elsewhere, and that it was therefore acceptable for it to decline the petition. He disagreed, however, with the majority's creation of a new presumption of unreviewability, calling it inconsistent with Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner's strong general presumption in favor of the opposite. He criticized the majority's use of precedent as unsupported by the case law, and took issue with their comparison to prosecutorial discretion, asserting that there are limits on its reach and that enforcement decisions, unlike prosecutorial decisions, deal much more often with situations in which nonenforcement denies someone a benefit or relief written into statue by Congress. He also criticized the prosecutorial discretion analogy on the grounds that the APA was designed to open agencies to judicial review, not shield them from it. Marshall contended that the majority's allowed exceptions to the presumption of unreviewability were too narrow, and that since an unreviewability test still involves examining an agency's rationale, it looks too similar to a deferential test on the merits in any case. "Easy cases", he remarked, "at times produce bad law". Marshall expressed the hope that over time, the majority's opinion would be interpreted as an expression of deference to agency expertise, rather than a full denial of the courts' role in agency action.[48]

Reaction, analysis, and impact

[edit]Judge Patricia M. Wald wrote:

Chaney is a precedent which, on its face, applies only to enforcement choices. Yet the broad language of the Court about why enforcement choices should not be reviewed, why deference should be given to agency expertise and to the agency's decision on how to deploy its limited resources, apply as well to other kinds of agency policymaking. Judges, who think the federal courts are reviewing too many decisions, read Chaney broadly as a signal to move forcefully to cut off review where Congress' directions to the agency are arguably vague or general. On the other hand, those judges more hospitable to judicial review of agency action register concern that taken too far, Chaney not only will cut off review of substantive legal issues and policies that inevitably take resource allocations into consideration, but will also permit agencies to insulate pure statutory interpretations about what a law means by dressing them up in the guise of enforcement decisions. In our circuit right now, judges are walking a tightrope between these polar views of Chaney.

Some scholars criticized the majority's rationale in creating a presumption of unreviewability. American legal scholar Bernard Schwartz was adamant that there is always "law to apply" in a system where "all discretionary power should be reviewable to determine that the discretion conferred has not been abused".[49] Ronald M. Levin wrote that Chaney upheld the part of Overton Park that was strongly criticized by continuing to bar nonstatutory claims of abuse of discretion.[50] William W. Templeton, writing for the Catholic University Law Review noted that prosecutorial discretion is limited by abuse of discretion. He also argues that prosecutorial decisions have "fundamental differences" from agency enforcement decisions, arguing that since prosecutors seek to punish violations of the law while agencies usually seek to prevent them, a court's refusal to review an agency nonenforcement decision has more potential for harm.[51] Cass Sunstein wrote that "it would probably be a mistake to read Chaney as establishing a general rule of nonreviewability for enforcement decisions", pointing out that the court carved out a substantial number of exceptions as questions to be answered by a later court.[52]

Lower courts largely accepted the Chaney decision without complaint in its immediate aftermath, applying the ruling to a swath of enforcement questions arising after it. Some expanded its reasoning beyond nonenforcement decisions, such as the Seventh Circuit's decision in Bethlehem Steel Corp. v. Environmental Protection Agency that the EPA's refusal to make a rule concerning the operation of coke ovens was unreviewable; others have refused to make that inference, such as the Eighth Circuit's decision in Iowa ex rel. Miller v. Block that the Department of Agriculture's refusal to implement an entire payment program was reviewable.[53]

Chaney's sentence had already been overturned the year before by the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit for an unrelated reason;[54] a state court subsequently converted it to life imprisonment. Had he been executed, he would have been the first person executed in Oklahoma by lethal injection.[7] Doyle Skillern was executed by lethal injection on January 16, 1985, in the Huntsville Walls Unit.[55]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The respondent here was Richard Schweiker, the Secretary of Health and Human Services.[11] The government appealed the DC Circuit decision under the name of Schweiker's successor, Margaret Heckler.[12]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Elliott 1984, p. 131.

- ^ a b Stolls 1985, p. 252.

- ^ Associated Press 1983.

- ^ a b Stolls 1985, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Percefull 1979.

- ^ Herman 1985.

- ^ a b Tulsa World 1985.

- ^ Associated Press 1981.

- ^ a b Templeton 1986, p. 1105.

- ^ a b Gamino 1981.

- ^ Chaney v. Schweiker.

- ^ Chaney v. Heckler.

- ^ Templeton 1986, p. 1106.

- ^ Congressional Research Service 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Werner 1986, pp. 1247.

- ^ Werner 1986, p. 1249. Quoting Senate Report 1945.

- ^ Werner 1986, p. 1250.

- ^ Levin 1990, pp. 706–707.

- ^ Sunstein 1985, p. 658.

- ^ Werner 1986, pp. 1250–1251.

- ^ Levin 1990, p. 711.

- ^ a b c d Sunstein 1985, p. 663.

- ^ "Congressional Research Service" 2014, p. 18.

- ^ Crittenden 1987, pp. 367

- ^ Templeton 1986, p. 1120.

- ^ Mikva 1986, p. 136-137.

- ^ Templeton 1986, p. 1123.

- ^ Crittenden 1987, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Crittenden 1987, pp. 371–372.

- ^ Chaney v. Heckler, 718 F.2d at 1030–1031 (Scalia, J., dissenting from denial of rehearing en banc).

- ^ Wald 1986, p. 513.

- ^ Levin 1990, p. 712.

- ^ a b c Sunstein 1985, p. 662.

- ^ Koch 1999, p. 71-72. Quoting "Heckler v. Chaney", 470 US at 832

- ^ Wald 1986, p. 513

- ^ Werner 1986, p. 1253

- ^ Sunstein 1986, p. 662

- ^ Sunstein 1985, p. 662;Werner 1986, p. 1253

- ^ Levin 1990, p. 713.

- ^ Congressional Research Service 2016, p. 12.

- ^ Werner 1986, pp. 1248–1255

- ^ Crittenden 1987, p. 373. Quoting Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. at 834.

- ^ "Congressional Research Service" 2014, p. 19.

- ^ Stolls 1985, p. 256.

- ^ Levin 1990, p. 719

- ^ Rowley 1986, p. 1045. Quoting Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. at 839 (Brennan, J., concurring).

- ^ Sunstein 1985, p. 664.

- ^ Crittenden 1987, pp. 374–376. Quoting Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. at 840 (Marshall, J., concurring).

- ^ Schwartz 1994, p. 169.

- ^ Levin 1990, pp. 713–714.

- ^ Templeton 1986, pp. 1121–1122, 1127.

- ^ Sunstein 1985, p. 675.

- ^ Crittenden 1987, pp. 376–377.

- ^ Jones & Stott 1984.

- ^ Bertling 1985.

Works cited

[edit]Academic sources

[edit]- Sunstein, Cass R. (1985). "Reviewing agency inaction after Heckler v. Chaney". University of Chicago Law Review. 52 (3): 653–683. doi:10.2307/1599631. JSTOR 1599631.

- Stolls, Michele (1985). "Heckler v. Chaney: judicial and administrative regulation of capital punishment by lethal injection". American Journal of Law & Medicine. 11 (2): 251. doi:10.1017/s0098858800008704.

- Elliott, E. Donald (1984). "Must the Drugs Used In Executions Be Approved as Safe and Effective". Preview of United States Supreme Court Cases. 1984 (6): 131.

- Rowley, Ace E. (1986). "Administrative inaction and judicial review: The rebuttable presumption of unreviewability". Missouri Law Review. 51: 1039.

- Mikva, Abner J. (1986). "The Changing Role of Judicial Review". Administrative Law Review. 38 (2).

- Werner, Sharon (1986). "The impact of Heckler v. Chaney on judicial review of agency decisions". Columbia Law Review. 86 (6): 1247–1266. doi:10.2307/1122658. JSTOR 1122658.

- Schwartz, Bernard (1994). "Apotheosis of Mediocrity: The Rehnquist Court and Administrative Law". Administrative Law Review. 46 (2). JSTOR 40709751.

- Wald, Patricia M. (1986). "The Changing Course: The Use of Precedent in the District of Columbia Circuit". Cleveland State Law Review. 34 (4).

- Templeton, William W. (1986). "Heckler v. Chaney: The new presumption of nonreviewability of agency enforcement decisions". Catholic University Law Review. 35: 1099.

- Crittenden, Elizabeth L. (1987). "Heckler v. Chaney: The presumption of unreviewability in administrative nonenforcement cases". West Virginia Law Review. 89: 363.

- Levin, Ronald M. (1990). "Understanding unreviewability in administrative law" (PDF). Minnesota Law Review. 74: 689.

- So Long as They Die: Lethal Injections in the United States (PDF). Human Rights Watch. 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- The Take Care Clause and Executive Discretion in the Enforcement of Law. Congressional Research Service. 2014.

- Koch, Charles H. (1999). "Unreviewability in State Administrative Law". Journal of the National Association of Administrative Law Judges.

Court cases

[edit]- Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner, 387 U.S. 136 (1967).

- Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971).

- Dunlop v. Bachowski, 421 U.S. 566 (1975).

- Chaney v. Schweiker (1982)—Memorandum Opinion filed August 30, 1982 in D.D.C. Civil Action No. 81-2265

- Chaney v. Heckler, 718 F.2d 1183.

- Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821 (1985).

Other sources

[edit]- Senate Report No. 752, 79th Congress, 1st Session, 26 (1945).

- 5 USC Ch. 7

- Percefull, Gary (December 4, 1979). "Chaney's attorney challenges death penalty". Tulsa World – via newspapers.com.

- "Drug execution plans challenged". Wichita Falls Times. Associated Press. January 8, 1981 – via newspapers.com.

- Gamino, Denise (August 28, 1981). "U.S. agency refuses to ban executions by drug injection". The Daily Oklahoman. Retrieved December 27, 2023 – via newspapers.com.

- "FDA ordered to approve execution drugs, or ban them". The Daily Herald. Associated Press. October 15, 1983 – via newspapers.com.

- Jones, Charles T.; Stott, Kim (March 22, 1984). "Death sentence in Chaney case". The Daily Oklahoman – via newspapers.com.

- Herman, Ken (January 6, 1985). "Inmate's execution nearing; triggerman may go free". The Marshall News Messenger. Associated Press – via newspapers.com.

- Bertling, Terry Scott (January 16, 1985). "Skillern prays family forgiveness just before lethal injection". Corpus Christi Times. Harte Hanks – via newspapers.com.

- "Chaney's death sentence changed to life imprisonment". Tulsa World. April 26, 1985 – via newspapers.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Text of Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821 (1985) is available from: Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio) LSU Law Center