History of Chinese Americans

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

The history of Chinese Americans or the history of ethnic Chinese in the United States includes three major waves of Chinese immigration to the United States, beginning in the 19th century. Chinese immigrants in the 19th century worked in the California Gold Rush of the 1850s and the Central Pacific Railroad in the 1860s. They also worked as laborers in Western mines. They suffered racial discrimination at every level of White society. Many Americans were stirred to anger by the "Yellow Peril" rhetoric. Despite provisions for equal treatment of Chinese immigrants in the 1868 Burlingame Treaty between the U.S. and China, political and labor organizations rallied against "cheap Chinese labor".

Newspapers condemned employers who were initially pro-Chinese. When clergy ministering to the Chinese immigrants in California supported the Chinese, they were severely criticized by the local press and populace.[1] So hostile was the opposition that in 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act prohibiting immigration from China for the following ten years. This law was then extended by the Geary Act in 1892. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the only U.S. law ever to prevent immigration and naturalization on the basis of race.[2] These laws not only prevented new immigration but also the reunion of the families of thousands of Chinese men already living in the United States who had left China without their wives and children. Anti-miscegenation laws in many Western states also prohibited the Chinese men from marrying white women.[3] In the South, many Chinese American men married African American women. For example, the tenth U.S. census of Louisiana alone showed 57% Chinese American men were married to African American women, and 43% to European American women.[4]

In 1924, the law barred further entries of Chinese. Those already in the United States had been ineligible for citizenship since the previous year. Also by 1924, all Asian immigrants (except people from the Philippines, which had been annexed by the United States in 1898) were utterly excluded by law, denied citizenship and naturalization, and prevented from owning land. In many Western states, Asian immigrants were even prevented from marrying Caucasians.[5]

Only since the 1940s, when the United States and China became allies during World War II, did the situation for Chinese Americans begin to improve, as restrictions on entry into the country, naturalization, and mixed marriage were lessened. In 1943, Chinese immigration to the United States was once again permitted—by way of the Magnuson Act—thereby repealing 61 years of official racial discrimination against the Chinese. Large-scale Chinese immigration did not occur until 1965 when the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965[6] lifted national origin quotas.[7] After World War II, anti-Asian prejudice began to decrease, and Chinese immigrants, along with other Asians (such as Japanese, Koreans, Indians and Vietnamese), have adapted and advanced. Currently, the Chinese constitute the largest ethnic group of Asian Americans (about 22%).

As of the 2020 U.S. census[update], there are more than 4.2 million Chinese in the United States, above 1.2% of the total population. The influx continues, where each year ethnic Chinese people from the People's Republic of China, Taiwan, and to a lesser extent Southeast Asia move to the United States, surpassing Hispanic and Latino immigration in 2012.[8]

Transpacific trade

[edit]

The Chinese reached North America during the era of Spanish colonial rule over the Philippines (1565–1815), during which they had established themselves as fishermen, sailors, and merchants on Spanish galleons that sailed between the Philippines and Mexican ports (Manila galleons). California belonged to Mexico until 1848, and historians have asserted that a small number of Chinese had already settled there by the mid-18th century. Also later, as part of expeditions in 1788 and 1789 by the explorer and fur trader John Meares from Canton to Vancouver Island, several Chinese sailors and craftsmen contributed to building the first European-designed boat that was launched in Vancouver.[10]

Shortly after the American Revolutionary War, as the United States had recently begun transpacific maritime trade with Qing, Chinese came into contact with American sailors and merchants at the commercial port of Canton (Guangzhou). There, local individuals heard about opportunities and became curious about America. The main trade route between the United States and China then was between Canton and New England, where the first Chinese arrived via Cape Horn (the only route as the Panama Canal did not exist). These Chinese were mainly merchants, sailors, seamen, and students who wanted to see and acquaint themselves with a strange foreign land they had only heard about. However, their presence was mostly temporary and only a few settled permanently.

American missionaries in China also sent small numbers of Chinese boys to the United States for schooling. From 1818 to 1825, five students stayed at the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, Connecticut. In 1854, Yung Wing became the first Chinese graduate from an American college, Yale University.[11] The Chinese Educational Mission of the 1870s-'80s continued this tradition, sending some 120 boys to be educated in New England schools.

During the Coolie Trade, Chinese laborers were subjected to harrowing conditions and forcibly transported to work in places like Cuba under exploitative contracts. Lau Chung Mun, Toishan Historian, recounted the way generations of his family were “sold like pigs” to work as coolies, when transported from China to Cuba for labour. Lau Chung Mun also informed that his father and uncle were the only survivors of 13 sent to work in Cuba.[12] The Chinese government sent an Imperial Mission to Cuba, to investigate working conditions and collected testimonies from labourers.[13] In the 1874 Cuba Commission Report, a laborer, Chang Kuan testified about working 21 hour days and enduring beatings. Another laborer, Chu Tsun-fang recounts a denial of his release papers on the termination of his contract, and confinement in prison for six years while labouring without receiving wages. Laborer, Lin Chin, remarked on the lack of dignity in death, explaining that the laborers’ bones were discarded in pits and forgotten.[14] The first hand testimonies from the Cuba Commission Report of 1874 provide vital insight into the abuse and dehumanization faced by Chinese Laborers during this period.

First wave: the beginning of Chinese immigration

[edit]

In the 19th century, Sino–U.S. maritime trade began the history of Chinese Americans. At first only a handful of Chinese came, mainly as merchants, former sailors, to America. The first Chinese people of this wave arrived in the United States around 1815. Subsequent immigrants that came from the 1820s up to the late 1840s were mainly men. In 1834, Afong Moy became the first female Chinese immigrant to the United States; she was brought to New York City from her home of Guangzhou by Nathaniel and Frederick Carne, who exhibited her as "the Chinese Lady".[15][16][17] By 1848, there were 325 Chinese Americans. 323 more immigrants came in 1849, 450 in 1850 and 20,000 in 1852 (2,000 in 1 day).[18] By 1852, there were 25,000; over 300,000 by 1880: a tenth of the Californian population—mostly from six districts of Canton (Guangdong) province (Bill Bryson, p. 143)[19]—who wanted to make their fortune in the 1849-era California Gold Rush. The Chinese did not, however, only come for the gold rush in California, but also helped build the First Transcontinental Railroad, worked Southern plantations after the Civil War, and participated in establishing California agriculture and fisheries.[20][21][22] Many were also fleeing the Taiping Rebellion that affected their region.

From the outset, they were met with the distrust and overt racism of settled European populations, ranging from massacres to pressuring Chinese migrants into what became known as Chinatowns.[23] In regard to their legal situation, the Chinese immigrants were far more imposed upon by the government than most other ethnic minorities in these regions. Laws were made to restrict them, including exorbitant special taxes (Foreign Miners' Tax Act of 1850), prohibiting them from marrying white European partners (so as to prevent men from marrying at all and increasing the population) and barring them from acquiring U.S. citizenship.[24]

Departure from China

[edit]

Decrees by the Qing dynasty issued in 1712 and 1724 forbade emigration and overseas trade and were primarily intended to prevent remnant supporters of the Ming dynasty from establishing bases overseas. However, these decrees were widely ignored. Large-scale immigration of Chinese laborers began after China began to receive news of deposits of gold found in California. The Burlingame Treaty with the United States in 1868 effectively lifted any former restrictions and large-scale immigration to the United States began.[25] In order to avoid difficulties with departure, most Chinese gold-seekers embarked on their transpacific voyage from the docks of Hong Kong, a major trading port in the region. Less frequently, they left from the neighboring port of Macau, with the choice usually being decided by distance of either city. Only merchants were able to take their wives and children overseas. The vast majority of Chinese immigrants were peasants, farmers and craftsmen. Young men, who were usually married, left their wives and children behind since they intended to stay in America only temporarily. Wives also remained behind to fulfill their traditional obligation to care for their husbands' parents. The men sent a large part of the money they earned in America back to China. Because it was usual at that time in China to live in confined social nets, families, unions, guilds, and sometimes whole village communities or even regions (for instance, Taishan) sent nearly all of their young men to California. From the beginning of the California Gold Rush until 1882—when an American federal law ended the Chinese influx—approximately 300,000 Chinese arrived in the United States. Because the chances to earn more money were far better in America than in China, these migrants often remained considerably longer than they had planned initially, despite increasing xenophobia and hostility towards them.[26]

Arrival in the United States

[edit]

Chinese immigrants booked their passages on ships with the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (founded in 1848) and the Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company (founded 1874). The money to fund their journey was mostly borrowed from relatives, district associations or commercial lenders. In addition, American employers of Chinese laborers sent hiring agencies to China to pay for the Pacific voyage of those who were unable to borrow money. This "credit-ticket system" meant that the money advanced by the agencies to cover the cost of the passage was to be paid back by wages earned by the laborers later during their time in the U.S. The credit-ticket system had long been used by indentured migrants from South China who left to work in what Chinese called Nanyang (South Seas), the region to the south of China that included the Philippines, the former Dutch East Indies, the Malay Peninsula, and Borneo, Thailand, Indochina, and Burma. The Chinese who left for Australia also used the credit-ticket system.[28]

The entry of the Chinese into the United States was, to begin with, legal and uncomplicated and even had a formal judicial basis in 1868 with the signing of the Burlingame Treaty between the United States and China. But there were differences compared with the policy for European immigrants, in that if the Chinese migrants had children born in the United States, those children would automatically acquire American citizenship. However, the immigrants themselves would legally remain as foreigners "indefinitely". Unlike European immigrants, the possibility of naturalization was withheld from the Chinese.[29]

Although the newcomers arrived in America after an already established small community of their compatriots, they experienced many culture shocks. The Chinese immigrants neither spoke nor understood English and were not familiar with Western culture and life; they often came from rural China and therefore had difficulty in adjusting to and finding their way around large towns such as San Francisco. The racism they experienced from the European Americans from the outset increased continuously until the turn of the 20th century, and with lasting effect prevented their assimilation into mainstream American society. This in turn led to the creation, cohesion, and cooperation of many Chinese benevolent associations and societies whose existence in the United States continued far into the 20th century as a necessity both for support and survival. There were also many other factors that hindered their assimilation, most notably their appearance. Under Qing dynasty law, Han Chinese men were forced under the threat of beheading to follow Manchu customs including shaving the front of their heads and combing the remaining hair into a queue. Historically, to the Manchus, the policy was both an act of submission and, in practical terms, an identification aid to tell friend from foe. Because Chinese immigrants returned as often as they could to China to see their family, they could not cut off their often hated braids in America and then legally re-enter China.[30]

The first Chinese immigrants usually remained faithful to traditional Chinese beliefs, which were either Confucianism, ancestral worship, Buddhism, or Taoism, while others adhered to various ecclesiastical doctrines. The number of Chinese migrants who converted to Christianity remained at first low. They were mainly Protestants who had already been converted in China where foreign Christian missionaries (who had first come in mass in the 19th century) had strived for centuries to wholly Christianize the nation with relatively minor success. Christian missionaries had also worked in the Chinese communities and settlements in America, but nevertheless their religious message found few who were receptive. It was estimated that during the first wave until the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, less than 20% of Chinese immigrants had accepted Christian teachings. Their difficulties with integration were exemplified by the end of the first wave in the mid-20th century when only a minority of Chinese living in the U.S. could speak English.[32]

Tanka people women who worked as prostitutes for foreigners also commonly kept a "nursery" of Tanka girls specifically to export them to overseas Chinese communities in Australia or America for prostitution work, or to serve as a Chinese or foreigner's concubine.[33] Of the first wave of Chinese who moved to America, few were women. In 1850, the Chinese community of San Francisco consisted of 4,018 men and only seven women. By 1855, women made up only two percent of the Chinese population in the United States, and even by 1890 this had only increased to 4.8 percent. The lack of visibility of Chinese women in general was due partially to the cost of making the voyage when there was a lack of work opportunities for Chinese women in America. This was exacerbated by the harsh working conditions and the traditional female responsibility of looking after the children and extended family back in China. The only women who did go to America were usually the wives of merchants. Other factors were cultural in nature, such as having bound feet and not leaving the home. Another important consideration was that most Chinese men were worried that by bringing their wives and raising families in America they too would be subjected to the same racial violence and discrimination they had faced. With the heavily uneven gender ratio, prostitution grew rapidly and the Chinese sex trade and trafficking became a lucrative business. Documents from the 1870 U.S. census show that 61 percent of 3,536 Chinese women in California were classified as prostitutes as an occupation. The existence of Chinese prostitution was detected early, after which the police, legislature and popular press singled out Chinese prostitutes for criticism. This was seen as further evidence of the depravity of the Chinese and the repression of women in their patriarchal cultural values.[34]

Laws passed by the California state legislature in 1866 to curb the brothels worked alongside missionary activity by the Methodist and Presbyterian Churches to help reduce the number of Chinese prostitutes. By the time of the 1880 U.S. census, documents show that only 24 percent of 3,171 Chinese women in California were classified as prostitutes, many of whom married Chinese Christians and formed some of the earliest Chinese American families in mainland America. Nevertheless, American legislation used the prostitution issue to make immigration far more difficult for Chinese women. On March 3, 1875, in Washington, D.C., the United States Congress enacted the Page Act that forbade the entry of all Chinese women considered "obnoxious" by representatives of U.S. consulates at their origins of departure. In effect, this led to American officials erroneously classifying many women as prostitutes, which greatly reduced the opportunities for all Chinese women wishing to enter the United States.[34] After the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, many Chinese Americans immigrated to the Southern states, particularly Arkansas, to work on plantations. The tenth U.S. census of Louisiana showed that 57% of interracial marriages between these Chinese American men were to African American women, and 43% to European American women.[4]

Formation of Chinese American associations

[edit]

Pre-1911 revolutionary Chinese society was distinctively collectivist and composed of close networks of extended families, unions, clan associations and guilds, where people had a duty to protect and help one another. Soon after the first Chinese had settled in San Francisco, respectable Chinese merchants—the most prominent members of the Chinese community of the time—made the first efforts to form social and welfare organizations (Chinese: "Kongsi") to help immigrants to relocate others from their native towns, socialize, receive monetary aid and raise their voices in community affairs.[36] At first, these organizations only provided interpretation, lodgings and job finding services for newcomers. In 1849, the first Chinese merchants' association was formed, but it did not last long. In less than a few years it petered out as its role was gradually replaced by a network of Chinese district and clan associations when more immigrants came in greater numbers.[36] Eventually some of the more prominent district associations banded together under one umbrella known as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (also known as the "Chinese Six Companies" because of the original six founding associations).[37] It quickly became the most powerful and politically vocal organization to represent the Chinese not only in San Francisco but in the whole of California. In other large cities and regions in America similar associations were formed.[36]

The Chinese associations mediated disputes and soon began participating in the hospitality industry, lending, health, and education and funeral services. The latter became especially significant for the Chinese community because for religious reasons many of the immigrants laid value to burial or cremation (including the scattering of ashes) in China. In the 1880s many of the city and regional associations united to form a national Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA), an umbrella organization, which defended the political rights and legal interests of the Chinese American community, particularly during times of anti-Chinese repression. By resisting overt discrimination enacted against them, the local chapters of the national CCBA helped to bring a number of cases to the courts from the municipal level to the Supreme Court to fight discriminatory legislation and treatment. The associations also took their cases to the press and worked with government institutions and Chinese diplomatic missions to protect their rights. In San Francisco's Chinatown, birthplace of the CCBA, formed in 1882, the CCBA had effectively assumed the function of an unofficial local governing body, which even used privately hired police or guards for protection of inhabitants at the height of anti-Chinese excesses.[38]

Following a law enacted in New York, in 1933, in an attempt to evict Chinese from the laundry business, the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance was founded as a competitor to the CCBA.

A minority of Chinese immigrants did not join the CCBA as they were outcasts or lacked the clan or family ties to join more prestigious Chinese surname associations, business guilds, or legitimate enterprises. As a result, they organized themselves into their own secret societies, called Tongs, for mutual support and protection of their members. These first tongs modeled themselves upon the triads, underground organizations dedicated to the overthrow of the Qing dynasty, and adopted their codes of brotherhood, loyalty, and patriotism.[40]

The members of the tongs were marginalized, poor, had lower educational levels and lacked the opportunities available to wealthier Chinese. Their organizations formed without any clear political or benevolent motives and soon found themselves involved in lucrative criminal activities, including extortion, gambling, people smuggling, and prostitution. Prostitution proved to be an extremely profitable business for the tongs, due to the high male-to-female ratio among the early immigrants. The tongs would kidnap or purchase females (including babies) from China and smuggle them over the Pacific Ocean to work in brothels and similar establishments. There were constant internecine battles over territory, profits, and women in feuds known as the tong wars, which began in the 1850s and lasted until the 1920s, notably in San Francisco, Cleveland, and Los Angeles.[40]

Fields of work for first wave immigrants

[edit]

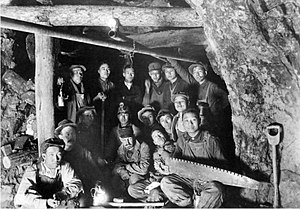

The Chinese moved to California in large numbers during the California Gold Rush, with 40,400 being recorded as arriving from 1851 to 1860, and again in the 1860s when the Central Pacific Railroad recruited large labor gangs, many on five-year contracts, to build its portion of the transcontinental railroad. The Chinese laborers worked out well and thousands more were recruited until the railroad's completion in 1869. Chinese labor provided the massive labor needed to build the majority of the Central Pacific's difficult railroad tracks through the Sierra Nevada mountains and across Nevada. The Chinese population rose from 2,716 in 1851 to 63,000 by 1871. In the decade 1861–1870, 64,301 were recorded as arriving, followed by 123,201 in 1871–1880 and 61,711 in 1881–1890. 77% were located in California, with the rest scattered across the West, the South, and New England.[41] Most came from Southern China looking for a better life; escaping a high rate of poverty left after the Taiping Rebellion. This immigration may have been as high as 90% male as most immigrated with the thought of returning home to start a new life. Those that stayed in America faced the lack of suitable Chinese brides as Chinese women were not allowed to emigrate in significant numbers after 1872. As a result, the mostly bachelor communities slowly aged in place with very low Chinese birth rates.

California Gold Rush

[edit]

The last major immigration wave started around the 1850s. The West Coast of North America was being rapidly settled by European Americans during the California Gold Rush, while southern China suffered from severe political and economic instability due to the weakness of the Qing government, along with massive devastation brought on by the Taiping Rebellion, which saw many Chinese emigrate to other countries to flee the fighting. As a result, many Chinese made the decision to emigrate from the chaotic Taishanese- and Cantonese-speaking areas in Guangdong province to the United States to find work, with the added incentive of being able to aid their family back home.

For most Chinese immigrants of the 1850s, San Francisco was only a transit station on the way to the gold fields in the Sierra Nevada. According to estimates, there were in the late 1850s 15,000 Chinese mine workers in the "Gold Mountains" or "Mountains of Gold" (Cantonese: Gam Saan, 金山). Because anarchic conditions prevailed in the gold fields, the robbery by European miners of Chinese mining area permits were barely pursued or prosecuted and the Chinese gold seekers themselves were often victim to violent assaults. At that time, "Chinese immigrants were stereotyped as degraded, exotic, dangerous, and perpetual foreigners who could not assimilate into civilized western culture, regardless of citizenship or duration of residency in the USA".[43] In response to this hostile situation these Chinese miners developed a basic approach that differed from the white European gold miners. While the Europeans mostly worked as individuals or in small groups, the Chinese formed large teams, which protected them from attacks and, because of good organization, often gave them a higher yield. To protect themselves even further against attacks, they preferred to work areas that other gold seekers regarded as unproductive and had given up on. One of the more violent incidents was a battle in 1861 with Native American miners who wanted to pan at Pike Flat which the land was own by the Chinese. So the two parties meet near a log cabin and drew two lines of battle and begin to fight with the Chinese successfully defending their clam.[44] Because much of the gold fields were exhaustingly gone over until the beginning of the 20th century, many of the Chinese remained far longer than the European miners. In 1870, one-third of the men in the Californian gold fields were Chinese.

However, their displacement had begun already in 1869 when white miners began to resent the Chinese miners, feeling that they were discovering gold that the white miners deserved. Eventually, protest rose from white miners who wanted to eliminate the growing competition. From 1852 to 1870 (ironically when the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was passed), the California legislature enforced a series of taxes.

In 1852, a special foreign miner's tax aimed at the Chinese was passed by the California legislature that was aimed at foreign miners who were not U.S. citizens. Given that the Chinese were ineligible for citizenship at that time and constituted the largest percentage of the non-white population of California, the taxes were primarily aimed at them and tax revenue was therefore generated almost exclusively by the Chinese.[41] This tax required a payment of three dollars each month at a time when Chinese miners were making approximately six dollars a month. Tax collectors could legally take and sell the property of those miners who refused or could not pay the tax. Fake tax collectors made money by taking advantage of people who could not speak English well, and some tax collectors, both false and real, stabbed or shot miners who could not or would not pay the tax. During the 1860s, many Chinese were expelled from the mine fields and forced to find other jobs. The Foreign Miner's Tax existed until 1870.[45]

The position of the Chinese gold seekers also was complicated by a decision of the California Supreme Court, which decided, in the case The People of the State of California v. George W. Hall in 1854 that the Chinese were not allowed to testify as witnesses before the court in California against white citizens, including those accused of murder. The decision was largely based upon the prevailing opinion that the Chinese were:

... a race of people whom nature has marked as inferior, and who are incapable of progress or intellectual development beyond a certain point, as their history has shown; differing in language, opinions, color, and physical conformation; between whom and ourselves nature has placed an impassable difference" and as such had no right " to swear away the life of a citizen" or participate" with us in administering the affairs of our Government.[46]

The ruling effectively made white violence against Chinese Americans unprosecutable, arguably leading to more intense white-on-Chinese race riots, such as the 1877 San Francisco riot. The Chinese living in California were with this decision left practically in a legal vacuum, because they had now no possibility to assert their rightful legal entitlements or claims—possibly in cases of theft or breaches of agreement—in court. The ruling remained in force until 1873.[47]

Transcontinental railroad

[edit]

After the gold rush wound down in the 1860s, the majority of the work force found jobs in the railroad industry. Chinese labor was integral to the construction of the first transcontinental railroad, which linked the railway network of the Eastern United States with California on the Pacific coast. Construction began in 1863 at the terminal points of Omaha, Nebraska and Sacramento, California, and the two sections were merged and ceremonially completed on May 10, 1869, at the famous "golden spike" event at Promontory Summit, Utah. It created a nationwide mechanized transportation network that revolutionized the population and economy of the American West. This network caused the wagon trains of previous decades to become obsolete, exchanging it for a modern transportation system. The building of the railway required enormous labor in the crossing of plains and high mountains by the Union Pacific Railroad and Central Pacific Railroad, the two privately chartered federally backed enterprises that built the line westward and eastward respectively.

Since there was a lack of white European construction workers, in 1865 a large number of Chinese workers were recruited from the silver mines, as well as later contract workers from China. The idea for the use of Chinese labor came from the manager of the Central Pacific Railroad, Charles Crocker, who at first had trouble persuading his business partners of the fact that the mostly weedy, slender looking Chinese workers, some contemptuously called "Crocker's pets", were suitable for the heavy physical work. For the Central Pacific Railroad, hiring Chinese as opposed to whites kept labor costs down by a third, since the company would not pay their board or lodging. This type of steep wage inequality was commonplace at the time.[41] Crocker overcame shortages of manpower and money by hiring Chinese immigrants to do much of the back-breaking and dangerous labor. He drove the workers to the point of exhaustion, in the process setting records for laying track and finishing the project seven years ahead of the government's deadline.[48]

The Central Pacific track was constructed primarily by Chinese immigrants. Even though at first they were thought to be too weak or fragile to do this type of work, after the first day in which Chinese were on the line, the decision was made to hire as many as could be found in California (where most were gold miners or in service industries such as laundries and kitchens). Many more were imported from China. Most of the men received between one and three dollars per day, but the workers from China received much less. Eventually, they went on strike and gained small increases in salary.[49]

The route laid not only had to go across rivers and canyons, which had to be bridged, but also through the Sierra Nevada mountains — where long tunnels had to be bored through solid granite using only hand tools and black powder. The explosions had caused many of the Chinese laborers to lose their lives. Due to the wide expanse of the work, the construction had to be carried out at times in the extreme heat and also in other times in the bitter winter cold. So harsh were the conditions that sometimes even entire camps were buried under avalanches.[50]

The Central Pacific made great progress along the Sacramento Valley. However construction was slowed, first by the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, then by the mountains themselves and most importantly by winter snowstorms. Consequently, the Central Pacific expanded its efforts to hire immigrant laborers (many of whom were Chinese). The immigrants seemed to be more willing to tolerate the horrible conditions, and progress continued. The increasing necessity for tunneling then began to slow progress of the line yet again. To combat this, Central Pacific began to use the newly invented and very unstable nitro-glycerine explosives—which accelerated both the rate of construction and the mortality of the Chinese laborers. Appalled by the losses, the Central Pacific began to use less volatile explosives, and developed a method of placing the explosives in which the Chinese blasters worked from large suspended baskets that were rapidly pulled to safety after the fuses were lit.[50]

The well organized Chinese teams still turned out to be highly industrious and exceedingly efficient; at the peak of the construction work, shortly before completion of the railroad, more than 11,000 Chinese were involved with the project. Although the white European workers had higher wages and better working conditions, their share of the workforce was never more than 10%. As the Chinese railroad workers lived and worked tirelessly, they also managed the finances associated with their employment, and Central Pacific officials responsible for employing the Chinese, even those at first opposed to the hiring policy, came to appreciate the cleanliness and reliability of this group of laborers.[51]

After 1869, the Southern Pacific Railroad and Northwestern Pacific Railroad led the expansion of the railway network further into the American West, and many of the Chinese who had built the transcontinental railroad remained active in building the railways.[52] After several projects were completed, many of the Chinese workers relocated and looked for employment elsewhere, such as in farming, manufacturing firms, garment industries, and paper mills. However, widespread anti-Chinese discrimination and violence from whites, including riots and murders, drove many into self-employment.

Agriculture

[edit]

Until the middle of the 19th century, wheat was the primary crop grown in California. The favorable climate allowed the beginning of the intensive cultivation of certain fruits, vegetables and flowers. In the East Coast of the United States a strong demand for these products existed. However, the supply of these markets became possible only with the completion of the transcontinental railroad. Just as with the railway construction, there was a dire manpower shortage in the expanding Californian agriculture sector, so the white landowners began in the 1860s to put thousands of Chinese migrants to work in their large-scale farms and other agricultural enterprises. Many of these Chinese laborers were not unskilled seasonal workers, but were in fact experienced farmers, whose vital expertise the Californian fruit, vegetables and wine industries owe much to this very day. Despite this, the Chinese immigrants could not own any land on account of the laws in California at the time. Nevertheless, they frequently pursued agricultural work under leases or profit-sharing contracts with their employers.[53]

Many of these Chinese men came from the Pearl River Delta Region in southern China, where they had learned how to develop fertile farmland in inaccessible river valleys. This know-how was used for the reclamation of the extensive valleys of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. During the 1870s, thousands of Chinese laborers played an indispensable role in the construction of a vast network of earthen levees in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta in California. These levees opened up thousands of acres of highly fertile marshlands for agricultural production. Chinese workers were used to construct hundreds of miles of levees throughout the delta's waterways in an effort to reclaim and preserve farmland and control flooding. These levees therefore confined waterflow to the riverbeds. Many of the workers stayed in the area and made a living as farm workers or sharecroppers, until they were driven out during an outbreak of anti-Chinese violence in the mid-1890s.

Chinese immigrants settled a few small towns in the Sacramento River delta, two of them: Locke, California, and Walnut Grove, California located 15–20 miles south of Sacramento were predominantly Chinese in the turn of the 20th century. Also Chinese farmers contributed to the development of the San Gabriel Valley of the Los Angeles area, followed by other Asian nationalities like the Japanese and Indians.

Military

[edit]A small number of Chinese fought during the American Civil War. Of the approximately 200 Chinese people in the eastern United States at the time, 58 are known to have fought in the Civil War, many of them in the Navy. Most fought for the Union, but a small number also fought for the Confederacy.[54]

Union soldiers with Chinese heritage

- Corporal Joseph Pierce, 14th Connecticut Infantry.[55]

- Corporal John Tomney/Tommy, 70th Regiment Excelsior Brigade, New York Infantry.[56]

- Edward Day Cohota, 23rd Massachusetts Infantry.[55][57]

- Antonio Dardelle, 27th Connecticut Regiment.[58]

- Hong Neok Woo, 50th Regiment Infantry, Pennsylvania Volunteer Emergency Militia.[59]

- Thomas Sylvanus, 42nd New York Infantry.[60]

- John Earl, cabin boy on USS Hartford.[61]

- William Hang, landsman on USS Hartford.[61]

- John Akomb, steward on a gunboat.[61]

Confederate soldiers with Chinese heritage[62]

- Christopher Wren Bunker and Stephen Decatur Bunker (Siam-born of partial Chinese ancestry), the sons of conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker. 37th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry.

- John Fouenty, draftee and deserter.

- Charles K. Marshall

Fisheries

[edit]

From the Pearl River Delta Region also came countless numbers of experienced Chinese fishermen. In the 1850s they founded a fishing economy on the Californian coast that grew exponentially, and by the 1880s extended along the whole West Coast of the United States, from Canada to Mexico. With entire fleets of small boats (sampans; 舢舨), the Chinese fishermen caught herring, soles, smelts, cod, sturgeon, and shark. To catch larger fish like barracudas, they used Chinese junks, which were built in large numbers on the American west coast. The catch included crabs, clams, abalone, salmon, and seaweed—all of which, including shark, formed the staple of Chinese cuisine. They sold their catch in local markets or shipped it salt-dried to East Asia and Hawaii.[64]

Again, this initial success was met with a hostile reaction. Since the late 1850s, European migrants—above all Greeks, Italians, and Dalmatians—moved into fishing off the American West Coast too, and they exerted pressure on the California legislature, which, finally, expelled the Chinese fishermen with a whole array of taxes, laws and regulations. They had to pay special taxes (Chinese Fisherman's Tax), and they were not allowed to fish with traditional Chinese nets nor with junks. The most disastrous effect occurred when the Scott Act, a federal U.S. law adopted in 1888, established that the Chinese migrants, even when they had entered and were living the United States legally, could not re-enter after having temporarily left U.S. territory. The Chinese fishermen, in effect, could therefore not leave with their boats the 3-mile (4.8 km) zone of the west coast.[65] Their work became unprofitable, and gradually they gave up fishing. The only area where the Chinese fishermen remained unchallenged was shark fishing, where they stood in no competition to the European Americans. Many former fishermen found work in the salmon canneries, which until the 1930s were major employers of Chinese migrants, because white workers were less interested in such hard, seasonal and relatively unrewarding work.[66]

Other occupations

[edit]

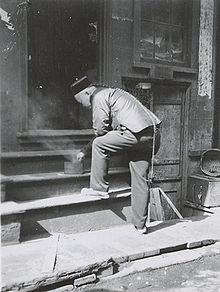

Since the California Gold Rush, many Chinese migrants made their living as domestic servants, housekeepers, running restaurants, laundries (leading to the 1886 Supreme Court decision Yick Wo v. Hopkins and then to the 1933 creation of the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance) and a wide spectrum of shops, such as food stores, antique shops, jewelers, and imported goods stores. In addition, the Chinese often worked in borax and mercury mines, as seamen on board the ships of American shipping companies or in the consumer goods industry, especially in the cigar, boots, footwear and textile manufacturing. During the economic crises of the 1870s, factory owners were often glad that the immigrants were content with the low wages given. The Chinese took the bad wages, because their wives and children lived in China where the cost of living was low. As they were classified as foreigners they were excluded from joining American trade unions, and so they formed their own Chinese organizations (called "guilds") that represented their interests with the employers. The American trade unionists were nevertheless still wary as the Chinese workers were willing to work for their employers for relatively low wages and incidentally acted as strikebreakers thereby running counter to the interests of the trade unions. In fact, many employers used the threat of importing Chinese strikebreakers as a means to prevent or break up strikes, which caused further resentment against the Chinese. A notable incident occurred in 1870, when 75 young men from China were hired to replace striking shoe workers in North Adams, Massachusetts.[67] Nevertheless, these young men had no idea that they had been brought from San Francisco by the superintendent of the shoe factory to act as strikebreakers at their destination. This incident provided the trade unions with propaganda, later repeatedly cited, calling for the immediate and total exclusion of the Chinese. This particular controversy slackened somewhat as attention focused on the economic crises in 1875 when the majority of cigar and boots manufacturing companies went under. Mainly, just the textile industry still employed Chinese workers in large numbers. In 1876, in response to the rising anti-Chinese hysteria, both major political parties included Chinese exclusion in their campaign platforms as a way to win votes by taking advantage of the nation's industrial crisis. Rather than directly confronting the divisive problems such as class conflict, economic depression, and rising unemployment, this helped put the question of Chinese immigration and contracted Chinese workers on the national agenda and eventually paved way for the era's most racist legislation, the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.[67][68]

Statistics on Employed Male Chinese in the Twenty, Most Frequently Reported Occupations, 1870

This table describes the occupation partitioning among Chinese males in the twenty most reported occupations.[69]

| # | Occupation | Population | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Miners | 17,069 | 36.9 |

| 2. | Laborers (not specified) | 9436 | 20.4 |

| 3. | Domestic servants | 5420 | 11.7 |

| 4. | Launderers | 3653 | 7.9 |

| 5. | Agricultural laborers | 1766 | 3.8 |

| 6. | Cigar-makers | 1727 | 3.7 |

| 7. | Gardeners & nurserymen | 676 | 1.5 |

| 8. | Traders & dealers(not specified) | 604 | 1.3 |

| 9. | Employees of railroad co., (not clerks) | 568 | 1.2 |

| 10. | Boot & shoemakers | 489 | 1.1 |

| 11. | Woodchoppers | 419 | 0.9 |

| 12. | Farmers & planters | 366 | 0.8 |

| 13. | Fishermen & oystermen | 310 | 0.7 |

| 14. | Barbers & hairdressers | 243 | 0.5 |

| 15. | Clerks in stores | 207 | 0.4 |

| 16. | Mill & factory operatives | 203 | 0.4 |

| 17. | Physicians & surgeons | 193 | 0.4 |

| 18. | Employees of manufacturing establishments | 166 | 0.4 |

| 19. | Carpenters & joiners | 155 | 0.3 |

| 20. | Peddlers | 152 | 0.3 |

| Sub-Total (20 occupations) | 43,822 | 94.7 | |

| Total (all occupations) | 46,274 | 100.0 |

Indispensable workforce

[edit]Supporters and opponents of Chinese immigration affirm[dubious – discuss] that Chinese labor was indispensable to the economic prosperity of the west. The Chinese performed jobs which could be life-threatening and arduous, for example working in mines, swamps, construction sites and factories. Many jobs that the Caucasians did not want to do were left to the Chinese. Some believed that the Chinese were inferior to the white people and so should be doing inferior work.[70]

Manufacturers depended on the Chinese workers because they had to reduce labor cost to save money and the Chinese labor was cheaper than the Caucasian labor. The labor from the Chinese was cheaper because they did not live like the Caucasians, they needed less money because they lived with lower standards.[71]

The Chinese were often in competition with African Americans in the labor market. In July 1869, in the Southern United States, at an immigration convention at Memphis, a committee was formed to consolidate schemes for importing Chinese laborers into the South like the African Americans.[72]

Anti-Chinese movement

[edit]

In the 1870s, several economic crises came about in parts of the United States, and many Americans lost their jobs, from which arose throughout the American West an anti-Chinese movement and its main mouthpiece, the Workingman's Party labor organization, which was led by the Californian Denis Kearney. The party took particular aim against Chinese immigrant labor and the Central Pacific Railroad that employed them. Its famous slogan was "The Chinese must go!" Kearney's attacks against the Chinese were particularly virulent and openly racist, and found considerable support among white people in the American West. This sentiment led eventually to the Chinese Exclusion Act and the creation of Angel Island Immigration Station. Their propaganda branded the Chinese migrants as "perpetual foreigners" whose work caused wage dumping and thereby prevented American men from "gaining work". After the 1893 economic downturn, measures adopted in the severe depression included anti-Chinese riots that eventually spread throughout the West from which came racist violence and massacres. Most of the Chinese farm workers, which by 1890 comprised 75% of all Californian agricultural workers, were expelled. The Chinese found refuge and shelter in the Chinatowns of large cities. The vacant agricultural jobs subsequently proved to be so unattractive to the unemployed white Europeans that they avoided the work; most of the vacancies were then filled by Japanese workers, after whom in the decades later came Filipinos, and finally Mexicans.[73] The term "Chinaman", originally coined as a self-referential term by the Chinese, came to be used as a term against the Chinese in America as the new term "Chinaman's chance" came to symbolize the unfairness Chinese experienced in the American justice system as some were murdered largely due to hatred of their race and culture.

Exclusion era

[edit]Settlement

[edit]

Across the country, Chinese immigrants clustered in Chinatowns. The largest population was in San Francisco. Large numbers came from the Taishan area that proudly bills itself as the No. 1 Home of Overseas Chinese. An estimated half a million Chinese Americans are of Taishanese descent.[74]

At first, when surface gold was plentiful, the Chinese were well tolerated and well received. As the easy gold dwindled and competition for it intensified, animosity to the Chinese and other foreigners increased. Organized labor groups demanded that California's gold was only for Americans, and began to physically threaten foreigners' mines or gold diggings. Most, after being forcibly driven from the mines, settled in Chinese enclaves in cities, mainly San Francisco, and took up low end wage labor such as restaurant work and laundry. A few settled in towns throughout the west. With the post Civil War economy in decline by the 1870s, anti-Chinese animosity became politicized by labor leader (and famous anti-Chinese advocate) Denis Kearney and his Workingman's Party as well as by Governor John Bigler, both of whom blamed Chinese "coolies" for depressed wage levels and causing European Americans to lose their jobs.

Discrimination

[edit]

The flow of immigration (encouraged by the Burlingame Treaty of 1868) was stopped by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. This act outlawed all Chinese immigration to the United States and denied citizenship to those already settled in the country. Renewed in 1892 and extended indefinitely in 1902, the Chinese population declined until the act was repealed in 1943 by the Magnuson Act.[41] (Chinese immigration later increased more with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which abolished direct racial barriers, and later by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which abolished the National Origins Formula.[75] ) Official discrimination extended to the highest levels of the U.S. government: in 1888, U.S. President Grover Cleveland, who supported the Chinese Exclusion Act, proclaimed the Chinese "an element ignorant of our constitution and laws, impossible of assimilation with our people and dangerous to our peace and welfare."[76]

Many Western states also enacted discriminatory laws that made it difficult for Chinese and Japanese immigrants to own land and find work. One of these anti-Chinese laws was the Foreign Miners' License tax, which required a monthly payment of three dollars from every foreign miner who did not desire to become a citizen. Foreign-born Chinese could not become citizens because they had been rendered ineligible to citizenship by the Naturalization Act of 1790 that reserved naturalized citizenship to "free white persons".[77]

By then, California had collected five million dollars from the Chinese. Another anti-Chinese law was "An Act to Discourage Immigration to this State of Persons Who Cannot Become Citizens Thereof", which imposed on the master or owner of a ship a landing tax of fifty dollars for each passenger ineligible to naturalized citizenship. "To Protect Free White Labor against competition with emigrant Chinese Labor and to Discourage the Immigration of Chinese into the State of California" was another such law (aka the Anti-Coolie Act, 1862), and it imposed a $2.50 tax per month on all Chinese residing in the state, except Chinese operating businesses, licensed to work in mines, or engaged in the production of sugar, rice, coffee or tea. In 1886, the Supreme Court struck down a Californian law, in Yick Wo v. Hopkins; this was the first case where the Supreme Court ruled that a law that is race-neutral on its face, but is administered in a prejudicial manner, is an infringement of the Equal Protection Clause in the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[78] The law aimed in particular against Chinese laundry businesses.

However, this Supreme Court decision was only a temporary setback for the Nativist movement. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act had made it unlawful for Chinese laborers to enter the United States for the next 10 years and denied naturalized citizenship to Chinese already here. Initially intended for Chinese laborers, it was broadened in 1888 to include all persons of the "Chinese race". And in 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson effectively canceled Yick Wo v. Hopkins, by supporting the "separate but equal" doctrine. Despite this, Chinese laborers and other migrants still entered the United States illegally through Canada and Latin America, in a path known as the Chinese Underground Railroad.[79]

Wong Kim Ark, who was born in San Francisco in 1873, was denied re-entry to the United States after a trip abroad, under a law restricting Chinese immigration and prohibiting immigrants from China from becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. However, he challenged the government's refusal to recognize his citizenship, and in the Supreme Court case United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898), the Court ruled regarding him that "a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicil and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China",[80] automatically became a U.S. citizen at birth.[81] This decision established an important precedent in its interpretation of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution.[82]

Tape v. Hurley, 66 Cal. 473 (1885) was a landmark court case in the California Supreme Court in which the Court found the exclusion of a Chinese American student, Mamie Tape, from public school based on her ancestry unlawful. However, state legislation passed at the urging of San Francisco Superintendent of Schools Andrew J. Moulder after the school board lost its case enabled the establishment of a segregated school.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Surgeon General Walter Wyman requested to put San Francisco's Chinatown under quarantine because of an outbreak of bubonic plague; the early stages of the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904. Chinese residents, supported by governor Henry Gage (1899–1903) and local businesses, fought the quarantine through numerous federal court battles, claiming the Marine Hospital Service was violating their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, and in the process, launched lawsuits against Kinyoun, director of the San Francisco Quarantine Station.[83]

The 1906 San Francisco earthquake allowed a critical change to Chinese immigration patterns. The practice known as "Paper Sons" and "Paper Daughters" was allegedly introduced. Chinese would declare themselves to be United States citizens whose records were lost in the earthquake.[84]

A year before, more than 60 labor unions formed the Asiatic Exclusion League in San Francisco, including labor leaders Patrick Henry McCarthy (mayor of San Francisco from 1910 to 1912), Olaf Tveitmoe (first president of the organization), and Andrew Furuseth and Walter McCarthy of the Sailor's Union. The League was almost immediately successful in pressuring the San Francisco Board of Education to segregate Asian school children.

California Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb (1902–1939) put great effort into enforcing the Alien Land Law of 1913, which he had co-written, and prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" (i.e. all Asian immigrants) from owning land or property. The law was struck down by the Supreme Court of California in 1946 (Sei Fujii v. State of California).[85]

One of the few cases in which Chinese immigration was allowed during this era were "Pershing's Chinese", 527 people who were allowed to immigrate from Mexico to the United States shortly before World War I as they aided General John J. Pershing in his expedition against Pancho Villa in Mexico.[86]

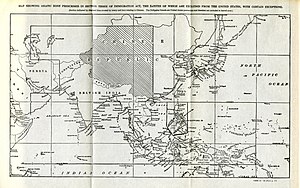

The Immigration Act of 1917 banned all immigration from many parts of Asia, including parts of China (see map on left), and foreshadowed the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924. Other laws included the Cubic Air Ordinance, which prohibited Chinese from occupying a sleeping room with less than 500 cubic feet (14 m3) of breathing space between each person, the Queue Ordinance,[87] which forced Chinese with long hair worn in a queue to pay a tax or to cut it, and Anti-Miscegenation Act of 1889 that prohibited Chinese men from marrying white women, and the Cable Act of 1922, which terminated citizenship for white American women who married an Asian man. The majority of these laws were not fully overturned until the 1950s, at the dawn of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Under all this persecution, almost half of the Chinese Americans born in the United States moved to China seeking greater opportunities.[88][89] Even to this day, discrimination is still talked about, especially for matters like Xenophobia[90] that we still experience in the 21st century.

Segregation in the South

[edit]Chinese immigrants first arrived in the Mississippi Delta during the Reconstruction Era as cheap laborers when the system of sharecropping was being developed.[91] They gradually came to operate grocery stores in mainly African American neighborhoods.[91] The Chinese population in the delta peaked in the 1870s, reaching 3000.[92]

Chinese carved out a distinct role in the predominantly biracial society of the Mississippi Delta. In a few communities, Chinese children were able to attend white schools, while others studied under tutors, or established their own Chinese schools.[93] In 1924, a nine-year-old Chinese American named Martha Lum, daughter of Gong Lum, was prohibited from attending the Rosedale Consolidated High School in Bolivar County, Mississippi, solely because she was of Chinese descent. The ensuing lawsuit eventually reached the Supreme Court of the United States. In Lum v. Rice (1927), the Supreme Court affirmed that the separate-but-equal doctrine articulated in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), applied to a person of Chinese ancestry, born in and a citizen of the United States. The court held that Miss Lum was not denied equal protection of the law because she was given the opportunity to attend a school which "receive[d] only children of the brown, yellow or black races". However, Chinese Americans in the Mississippi Delta began to identify themselves with whites and ended their friendship with the black community in Mississippi.[citation needed] By the late 1960s, Chinese American children attended white schools and universities. They joined Mississippi's infamous White citizen's councils, became members of white churches, were defined as white on driver's licenses, and could marry whites.[94]

Chinatown: Slumming, gambling, prostitution, and opium

[edit]In his book published in 1890, How The Other Half Lives, Jacob Riis called the Chinese of New York "a constant and terrible menace to society",[95] "in no sense a desirable element of the population".[96] Riis referred to the reputation of New York's Chinatown as a place full of illicit activity, including gambling, prostitution, and opium smoking. To some extent, Riis' characterization was true, though the sensational press quite often exploited the great differences between Chinese and American language and culture to sell newspapers,[97] exploit Chinese labor and promote Americans of European birth. The press in particular greatly exaggerated the prevalence of opium smoking and prostitution in New York's Chinatown, and many reports of indecency and immorality were simply fictitious.[98] Casual observers of Chinatown believed that opium use was rampant since they constantly witnessed Chinese smoking with pipes. In fact, local Chinatown residents often were instead smoking tobacco through such pipes.[99] In the late 19th century, many European Americans visited Chinatown to experience it via "slumming", wherein guided groups of affluent New Yorkers explored vast immigrant districts of New York such as the Lower East Side.[100] Slummers often frequented the brothels and opium dens of Chinatown in the late 1880s and early 1890s.[101] However, by the mid-1890s, slummers rarely participated in Chinese brothels or opium smoking, but instead were shown fake opium joints where Chinese actors and their white wives staged illicit and exaggerated scenes for their audiences.[101] Quite often such shows, which included gunfights that mimicked those of local tongs, were staged by professional guides or "lobbygows"—often Irish Americans—with paid actors.[102] Especially in New York, the Chinese community was unique among immigrant communities in so far as its illicit activity was turned into a cultural commodity.

Perhaps the most pervasive illicit activity in Chinatowns of the late-19th century was gambling. In 1868, one of the earliest Chinese residents in New York, Wah Kee, opened a fruit and vegetable store on Pell Street with rooms upstairs available for gambling and opium smoking.[103] A few decades later, local tongs, which originated in the California goldfields around 1860, controlled most gambling (fan-tan, faro, lotteries) in New York's Chinatown.[98] One of the most popular games of chance was fan-tan where players guessed the exact coins or cards left under a cup after a pile of cards had been counted off four at a time.[104] Most popular, however, was the lottery. Players purchased randomly assigned sweepstakes numbers from gambling-houses, with drawings held at least once a day in lottery saloons.[105] There were ten such saloons found in San Francisco in 1876, which received protection from corrupt policemen in exchange for weekly payoffs of around five dollars per week.[105] Such gambling-houses were frequented by as many whites as Chinamen, though whites sat at separate tables.[106]

Between 1850 and 1875, the most frequent complaint against Chinese residents was their involvement in prostitution.[107] There was a great excess of Chinses men in America, which was caused by coolie trade[6] and anti-miscegenation law against Chinese men.[7] High demand in sex inevitably led to prostitution.[3] During this time, Hip Yee Tong, a secret society, imported over six-thousand Chinese women to serve as prostitutes.[108] Most of these women came from southeastern China and were either kidnapped, purchased from poor families, or lured to ports like San Francisco with the promise of marriage.[108] Prostitutes fell into three categories, namely, those sold to wealthy Chinese merchants as concubines, those purchased for high-class Chinese brothels catering exclusively to Chinese men, or those purchased for prostitution in lower-class establishments frequented by a mixed clientele.[108] In late-19th century San Francisco, most notably Jackson Street, prostitutes were often housed in rooms 10×10 or 12×12 feet and were often beaten or tortured for not attracting enough business or refusing to work for any reason.[109] In San Francisco, "highbinders" (various Chinese gangs) protected brothel owners, extorted weekly tributes from prostitutes and caused general mayhem in Chinatown.[110] However, many of San Francisco's Chinatown whorehouses were located on property owned by high-ranking European American city officials, who took a percentage of the proceeds in exchange for protection from prosecution.[111] From the 1850s to the 1870s, California passed numerous acts to limit prostitution by all races, yet only Chinese were ever prosecuted under these laws.[112] After the Thirteenth Amendment was passed in 1865, Chinese women brought to the United States for prostitution signed a contract so that their employers would avoid accusations of slavery.[108] Many Americans believed that Chinese prostitutes were corrupting traditional morality, and thus the Page Act was passed in 1875, which placed restrictions on female Chinese immigration. Those who supported the Page Act were attempting to protect American family values, while those who opposed the Act were concerned that it might hinder the efficiency of the cheap labor provided by Chinese males.[113]

In the mid 1850s, 70 to 150 Chinese lived in New York City, of which 11 married Irish women. The New York Times reported on August 6, 1906 that 300 white women (Irish American) were married to Chinese men in New York, with many more cohabiting. Research carried out in 1900 by Liang showed that of the 120,000 men in more than 20 Chinese communities in the United States, one out of every twenty Chinese men (Cantonese) was married to a white woman.[114] At the start of the 20th century there was a 55% rate of Chinese men in New York engaging in interracial marriage, which was maintained in the 1920s, but by the 1930s it had fallen to 20%.[115] It is after the migration of Chinese females in equal number to Chinese males that intermarriage became more balanced. The 1960s census showed 3500 Chinese men married to white women and 2900 Chinese women married to white men. The census also showed 300 Chinese men married black women and 100 black men married Chinese women.[116]

It was far more common for Chinese males to marry non-white females in many states. One of the U.S. censuses of Louisiana alone in 1880 showed 57% Chinese American men were married to African American women, and 43% to White American women.[117] As a result of miscegenation laws against Chinese males. Many Chinese males either cohibited their relationship in secret or married with black females. Of the Chinese men who lived in Mississippi, 20% and 30% of the Chinese males had married black women in many different years before 1940.[118]

Another major concern of European Americans in relation to Chinatowns was the smoking of opium, even though the practice of smoking opium in America long predated Chinese immigration to the United States.[119] Tariff acts of 1832 established opium regulation, and in 1842 opium was taxed at seventy-five cents per pound.[120] In New York, by 1870, opium dens had opened on Baxter and Mott Streets in Manhattan Chinatown,[120] while in San Francisco, by 1876, Chinatown supported over 200 opium dens, each with a capacity of between five and fifteen people.[120] After the Burlingame Commercial Treaty of 1880, only American citizens could legally import opium into the United States, and thus Chinese businessmen had to rely on non-Chinese importers to maintain opium supply. Ultimately, it was European Americans who were largely responsible for the legal importation and illegal smuggling of opium via the port of San Francisco and the Mexican border, after 1880.[120]

Since the early 19th century, opium was widely used as an ingredient in medicines, cough syrups, and child quieters.[121] However, many 19th century doctors and opium experts, such as Dr. H.H. Kane and Dr. Leslie E. Keeley, made a distinction between opium used for smoking and that used for medicinal purposes, though they found no difference in addictive potential between them.[122] As part of a larger campaign to rid the United States of Chinese influence, white American doctors claimed that opium smoking led to increased involvement in prostitution by young white women and to genetic contamination via miscegenation.[123] Anti-Chinese advocates believed America faced a dual dilemma: opium smoking was ruining moral standards, and Chinese labor was lowering wages and taking jobs away from European Americans.[124]

Second wave (1949 to the 1980s)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

The Magnuson Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943, was proposed by U.S. Representative (later Senator) Warren G. Magnuson of Washington and signed into law on December 17, 1943. It allowed Chinese immigration for the first time since the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and permitted Chinese nationals already residing in the country to become naturalized citizens. This marked the first time since the Naturalization Act of 1790 that any Asians were permitted to naturalize.

The Magnuson Act passed during World War II, when China was a welcome ally to the United States. It limited Chinese immigrants to 105 visas per year selected by the government. That quota was supposedly determined by the Immigration Act of 1924, which set immigration from an allowed country at 2% of the number of people of that nationality who already lived in the United States in 1890. Chinese immigration later increased with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965, but was in fact set ten times lower.[125]

Many of the first Chinese immigrants admitted in the 1940s were college students who initially sought simply to study in, not immigrate to, America. However, during the Second Red Scare, conservative American politicians reacted to the emergence of the People's Republic of China as a player in the Cold War by demanding that these Chinese students be prevented from returning to "Red China". It was feared by these politicians (and no small amount of their constituents) that, if they were allowed to return home to the PRC, they would furnish America's newfound Cold War enemy with valuable scientific knowledge. Therefore, Chinese students were heavily encouraged to undergo naturalization. One famous Chinese immigrant of the 1940s generation was Tsou Tang, who would eventually become the leading American expert on China and Sino-American relations during the Cold War.[126]

With the rise in immigration and expansion of communities, newspaper and media outlets grew as well. William Y. Chang founded the Chinese-American Times newspaper in 1955 to provide a venue through which Chinese American communities could read and write about their own lives.[127]

According to historian of the American West, Gunther Barth, of the 237,293 Chinese Americans (immigrants and natural-born citizens) who lived in the United States in 1960, three-fourths resided in California (40% of the 237,293), New York (16%), and Hawaii (16%). This shows how concentrated Chinese American populations remained during the second wave of immigration and illustrates how most people of Chinese descent stayed close to Chinese American communities.[128]

Until 1979, the United States recognized the Republic of China in Taiwan as the sole legitimate government of all of China, and immigration from Taiwan was counted under the same quota as that for mainland China, which had little immigration to the United States from 1949 to 1977. In the late 1970s, the opening up of the People's Republic of China and the breaking of diplomatic relations with the Republic of China led to the passage in 1979 of the Taiwan Relations Act, which placed Taiwan under a separate immigration quota from the People's Republic of China. Emigration from Hong Kong was also considered a separate jurisdiction for the purpose of recording such statistics, and this status continued until the present day as a result of the Immigration Act of 1990.

Chinese Muslims have immigrated to the United States and lived within the Chinese community rather than integrating into other foreign Muslim communities. Two of the most prominent Chinese American Muslims are the Republic of China National Revolutionary Army Generals Ma Hongkui and his son Ma Dunjing who moved to Los Angeles after fleeing from China to Taiwan. Pai Hsien-yung is another Chinese Muslim writer who moved to the United States after fleeing from China to Taiwan, his father was the Chinese Muslim General Bai Chongxi.

Ethnic Chinese immigration to the United States since 1965 has been aided by the fact that the United States maintains separate quotas for Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. During the late 1960s and early and mid-1970, Chinese immigration into the United States came almost exclusively from Hong Kong and Taiwan creating the Hong Kong American and Taiwanese American subgroups. Immigration from Mainland China was almost non-existent until 1977 when the PRC removed restrictions on emigration leading to the immigration of college students and professionals. These recent groups of Chinese tended to cluster in suburban areas and avoided urban Chinatowns.

Third wave (1980s to today)

[edit]

In addition to students and professionals, a recent third wave of immigrants, many of which entered the country without documentation (illegally), are people who travelled to the United States in search of lower-status manual labor jobs. These illegal immigrants tend to concentrate in heavily urban areas, particularly in New York City, and there is often very little contact between these Chinese and those higher-educated Chinese professionals. Quantification of the magnitude of this modality of immigration is imprecise and varies over time, but it appears to continue unabatedly on a significant basis. In the 1980s, there was widespread concern by the PRC over a brain drain as graduate students were not returning to the PRC. This exodus worsened after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. However, since the start of the 21st century, there have been an increasing number of returnees producing a brain gain for the PRC.[129]

Starting from the 1990s, the demographics of the Chinese American community have shifted in favor of immigrants with roots in mainland China, rather than from Taiwan or Hong Kong. However, instead of joining existing Chinese American associations, the recent immigrants formed new cultural, professional, and social organizations which advocated better Sino-American relations, as well as Chinese schools which taught simplified Chinese characters and pinyin. The National Day of the People's Republic of China is now celebrated in some Chinatowns, and flag raising ceremonies feature the Flag of the People's Republic of China as well as the older ROC flag.[130] The effects of Taiwanization, growing prosperity in the PRC, and successive pro-Taiwan independence governments on Taiwan have served to split the older Chinese American community,[131] as some pro-reunification Chinese Americans with ROC origins began to identify more with the PRC.[130]

As pursuant to the Department of Homeland security 2016 immigration report the major class of admission for those Chinese immigrants entering into the US is through Immediate Relatives of US citizens.[132] Just over a third (30,456) of those immigrants gained entry via this means. As legislation in the US is seen to favour this point of entry. Furthermore, employment based preferences is seen to be the third largest. This means of entry accounts for 23% of the total. The H1-B visa is seen to be a main point of entry for Chinese immigrants with both India and China dominating this visa category over the last ten years.[133] Unsurprisingly, Chinese immigrants entering the United States via the diversity lottery are low. This means of entry prioritises those entering into the US from countries with historically low number of immigrants. As such, China does not fall into this category.[134]

Drawing on United States Census Bureau data, the Pew Research Data Center notes that 54% of Asian immigrants ages five and over who have been in the United States for five years or less say they speak English proficiently. This means that some of the main challenges Asian immigrants face in the United States today are language barriers.[135]

Statistics of the Chinese population in the United States (1840–2010)

[edit]

The table shows the ethnic Chinese population of the United States (including persons with mixed-ethnic origin).[136]

| Year | Total U.S. population | Of Chinese origin | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 17,069,453 | not available | n/a |

| 1850 | 23,191,876 | 4,018 | 0.02% |

| 1860 | 31,443,321 | 34,933 | 0.11% |

| 1870 | 38,558,371 | 64,199 | 0.17% |

| 1880 | 50,189,209 | 105,465 | 0.21% |

| 1890 | 62,979,766 | 107,488 | 0.17% |

| 1900 | 76,212,168 | 118,746 | 0.16% |

| 1910 | 92,228,496 | 94,414 | 0.10% |

| 1920 | 106,021,537 | 85,202 | 0.08% |

| 1930 | 123,202,624 | 102,159 | 0.08% |

| 1940 | 132,164,569 | 106,334 | 0.08% |

| 1950 | 151,325,798 | 150,005 | 0.10% |

| 1960 | 179,323,175 | 237,292 | 0.13% |

| 1970 | 203,302,031 | 436,062 | 0.21% |

| 1980 | 226,542,199 | 812,178 | 0.36% |

| 1990 | 248,709,873 | 1,645,472 | 0.66% |

| 2000 | 281,421,906 | 2,432,585 | 0.86% |

| 2010 | 308,745,538 | 3,794,673 | 1.23% |

| 2020 | 331,449,281 | 5,400,000 | 1.63% |

See also

[edit]- Anti-Chinese sentiment in the United States

- History of Asian American immigration

- Chinese emigration

- Overseas Chinese

- Immigration to the United States

- Illegal immigration to the United States

- Racism in the United States

- History of the United States

- Chinese Canadian

- History of Chinese immigration to Canada

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Seager II, Robert (February 1959). "Some Denominational Reactions to Chinese Immigration to California, 1856-1892". Pacific Historical Review. 28 (1). University of California Press: Pacific Historical Review Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 49-66: 49–66. doi:10.2307/3636239. JSTOR 3636239.

- ^ Chin, Gabriel J., (1998) UCLA Law Review vol. 46, at 1 "Segregation's Last Stronghold: Race Discrimination and the Constitutional Law of Immigration"

- ^ a b Chin, Gabriel and Hrishi Karthikeyan, (2002) Asian Law Journal vol. 9 "Preserving Racial Identity: Population Patterns and the Application of Anti-Miscegenation Statutes to Asian Americans, 1910–1950"

- ^ a b "The United States". Chinese blacks in the Americas. Color Q World. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ Bernfeld, Beatrice (May–June 2000), Asian Pacific Americans-enriching the evolving American culture, archived from the original on 2006-05-07, retrieved 2007-09-01

- ^ a b Gabriel J. Chin, "The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law: A New Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965," 75 North Carolina Law Review 273(1996)

- ^ a b "Chinese communities shifting to Mandarin", AP, 2003-12-29, archived from the original on 2004-06-04, retrieved 2013-09-18

- ^ "The Rise of Asian Americans". Pew Social and Demographic Trends: reports. Pew Research Center. June 19, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Canton – harbor crowded with sampans. Jackson, William Henry, 1843–1942. World's Transportation Commission photograph collection (Library of Congress).

- ^ Brownstone, p.25

- ^ Brownstone, pp.2, 25

- ^ Lau, Chungmun. Ancestors in the Americas. 2001. Kanopy, https://www.kanopy.com/en/bmcccuny/video/594028/594030.

- ^ Government of China; Imperial Mission, et al. The Cuba Commission Report. Investigation into working conditions of Chinese Laborers in Cuba and laborer testimonies. 1874.

- ^ Ding, Loni, director. “Coolies, Sailors, Settlers: Voyage to the New World.” Ancestors in the Americas, season 1, episode 1, CET Films, 2001. Kanopy, https://www.kanopy.com/en/bmcccuny/video/594028/594030.

- ^ Wei Chi Poon. "The Life Experiences of Chinese Women in the U.S." Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- ^ "The First Chinese Women in the United States". The National Women's History Museum. Archived from the original on September 5, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.