Computer

- Early vacuum tube computer (ENIAC)

- Mainframe computer (IBM System 360)

- Smartphone (LYF Water 2)

- Desktop computer (IBM ThinkCentre S50 with monitor)

- Video game console (Nintendo GameCube)

- Supercomputer (IBM Summit)

A computer is a machine that can be programmed to automatically carry out sequences of arithmetic or logical operations (computation). Modern digital electronic computers can perform generic sets of operations known as programs. These programs enable computers to perform a wide range of tasks. The term computer system may refer to a nominally complete computer that includes the hardware, operating system, software, and peripheral equipment needed and used for full operation; or to a group of computers that are linked and function together, such as a computer network or computer cluster.

A broad range of industrial and consumer products use computers as control systems, including simple special-purpose devices like microwave ovens and remote controls, and factory devices like industrial robots. Computers are at the core of general-purpose devices such as personal computers and mobile devices such as smartphones. Computers power the Internet, which links billions of computers and users.

Early computers were meant to be used only for calculations. Simple manual instruments like the abacus have aided people in doing calculations since ancient times. Early in the Industrial Revolution, some mechanical devices were built to automate long, tedious tasks, such as guiding patterns for looms. More sophisticated electrical machines did specialized analog calculations in the early 20th century. The first digital electronic calculating machines were developed during World War II, both electromechanical and using thermionic valves. The first semiconductor transistors in the late 1940s were followed by the silicon-based MOSFET (MOS transistor) and monolithic integrated circuit chip technologies in the late 1950s, leading to the microprocessor and the microcomputer revolution in the 1970s. The speed, power, and versatility of computers have been increasing dramatically ever since then, with transistor counts increasing at a rapid pace (Moore's law noted that counts doubled every two years), leading to the Digital Revolution during the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

Conventionally, a modern computer consists of at least one processing element, typically a central processing unit (CPU) in the form of a microprocessor, together with some type of computer memory, typically semiconductor memory chips. The processing element carries out arithmetic and logical operations, and a sequencing and control unit can change the order of operations in response to stored information. Peripheral devices include input devices (keyboards, mice, joysticks, etc.), output devices (monitors, printers, etc.), and input/output devices that perform both functions (e.g. touchscreens). Peripheral devices allow information to be retrieved from an external source, and they enable the results of operations to be saved and retrieved.

Etymology

It was not until the mid-20th century that the word acquired its modern definition; according to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first known use of the word computer was in a different sense, in a 1613 book called The Yong Mans Gleanings by the English writer Richard Brathwait: "I haue [sic] read the truest computer of Times, and the best Arithmetician that euer [sic] breathed, and he reduceth thy dayes into a short number." This usage of the term referred to a human computer, a person who carried out calculations or computations. The word continued to have the same meaning until the middle of the 20th century. During the latter part of this period, women were often hired as computers because they could be paid less than their male counterparts.[1] By 1943, most human computers were women.[2]

The Online Etymology Dictionary gives the first attested use of computer in the 1640s, meaning 'one who calculates'; this is an "agent noun from compute (v.)". The Online Etymology Dictionary states that the use of the term to mean "'calculating machine' (of any type) is from 1897." The Online Etymology Dictionary indicates that the "modern use" of the term, to mean 'programmable digital electronic computer' dates from "1945 under this name; [in a] theoretical [sense] from 1937, as Turing machine".[3] The name has remained, although modern computers are capable of many higher-level functions.

History

Pre-20th century

Devices have been used to aid computation for thousands of years, mostly using one-to-one correspondence with fingers. The earliest counting device was most likely a form of tally stick. Later record keeping aids throughout the Fertile Crescent included calculi (clay spheres, cones, etc.) which represented counts of items, likely livestock or grains, sealed in hollow unbaked clay containers.[a][4] The use of counting rods is one example.

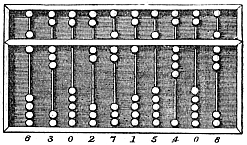

The abacus was initially used for arithmetic tasks. The Roman abacus was developed from devices used in Babylonia as early as 2400 BCE. Since then, many other forms of reckoning boards or tables have been invented. In a medieval European counting house, a checkered cloth would be placed on a table, and markers moved around on it according to certain rules, as an aid to calculating sums of money.[5]

The Antikythera mechanism is believed to be the earliest known mechanical analog computer, according to Derek J. de Solla Price.[6] It was designed to calculate astronomical positions. It was discovered in 1901 in the Antikythera wreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, between Kythera and Crete, and has been dated to approximately c. 100 BCE. Devices of comparable complexity to the Antikythera mechanism would not reappear until the fourteenth century.[7]

Many mechanical aids to calculation and measurement were constructed for astronomical and navigation use. The planisphere was a star chart invented by Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī in the early 11th century.[8] The astrolabe was invented in the Hellenistic world in either the 1st or 2nd centuries BCE and is often attributed to Hipparchus. A combination of the planisphere and dioptra, the astrolabe was effectively an analog computer capable of working out several different kinds of problems in spherical astronomy. An astrolabe incorporating a mechanical calendar computer[9][10] and gear-wheels was invented by Abi Bakr of Isfahan, Persia in 1235.[11] Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī invented the first mechanical geared lunisolar calendar astrolabe,[12] an early fixed-wired knowledge processing machine[13] with a gear train and gear-wheels,[14] c. 1000 AD.

The sector, a calculating instrument used for solving problems in proportion, trigonometry, multiplication and division, and for various functions, such as squares and cube roots, was developed in the late 16th century and found application in gunnery, surveying and navigation.

The planimeter was a manual instrument to calculate the area of a closed figure by tracing over it with a mechanical linkage.

The slide rule was invented around 1620–1630, by the English clergyman William Oughtred, shortly after the publication of the concept of the logarithm. It is a hand-operated analog computer for doing multiplication and division. As slide rule development progressed, added scales provided reciprocals, squares and square roots, cubes and cube roots, as well as transcendental functions such as logarithms and exponentials, circular and hyperbolic trigonometry and other functions. Slide rules with special scales are still used for quick performance of routine calculations, such as the E6B circular slide rule used for time and distance calculations on light aircraft.

In the 1770s, Pierre Jaquet-Droz, a Swiss watchmaker, built a mechanical doll (automaton) that could write holding a quill pen. By switching the number and order of its internal wheels different letters, and hence different messages, could be produced. In effect, it could be mechanically "programmed" to read instructions. Along with two other complex machines, the doll is at the Musée d'Art et d'Histoire of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, and still operates.[15]

In 1831–1835, mathematician and engineer Giovanni Plana devised a Perpetual Calendar machine, which through a system of pulleys and cylinders could predict the perpetual calendar for every year from 0 CE (that is, 1 BCE) to 4000 CE, keeping track of leap years and varying day length. The tide-predicting machine invented by the Scottish scientist Sir William Thomson in 1872 was of great utility to navigation in shallow waters. It used a system of pulleys and wires to automatically calculate predicted tide levels for a set period at a particular location.

The differential analyser, a mechanical analog computer designed to solve differential equations by integration, used wheel-and-disc mechanisms to perform the integration. In 1876, Sir William Thomson had already discussed the possible construction of such calculators, but he had been stymied by the limited output torque of the ball-and-disk integrators.[16] In a differential analyzer, the output of one integrator drove the input of the next integrator, or a graphing output. The torque amplifier was the advance that allowed these machines to work. Starting in the 1920s, Vannevar Bush and others developed mechanical differential analyzers.

In the 1890s, the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo began to develop a series of advanced analog machines that could solve real and complex roots of polynomials,[17][18][19][20] which were published in 1901 by the Paris Academy of Sciences.[21]

First computer

Charles Babbage, an English mechanical engineer and polymath, originated the concept of a programmable computer. Considered the "father of the computer",[22] he conceptualized and invented the first mechanical computer in the early 19th century.

After working on his difference engine he announced his invention in 1822, in a paper to the Royal Astronomical Society, titled "Note on the application of machinery to the computation of astronomical and mathematical tables".[23] He also designed to aid in navigational calculations, in 1833 he realized that a much more general design, an analytical engine, was possible. The input of programs and data was to be provided to the machine via punched cards, a method being used at the time to direct mechanical looms such as the Jacquard loom. For output, the machine would have a printer, a curve plotter and a bell. The machine would also be able to punch numbers onto cards to be read in later. The engine would incorporate an arithmetic logic unit, control flow in the form of conditional branching and loops, and integrated memory, making it the first design for a general-purpose computer that could be described in modern terms as Turing-complete.[24][25]

The machine was about a century ahead of its time. All the parts for his machine had to be made by hand – this was a major problem for a device with thousands of parts. Eventually, the project was dissolved with the decision of the British Government to cease funding. Babbage's failure to complete the analytical engine can be chiefly attributed to political and financial difficulties as well as his desire to develop an increasingly sophisticated computer and to move ahead faster than anyone else could follow. Nevertheless, his son, Henry Babbage, completed a simplified version of the analytical engine's computing unit (the mill) in 1888. He gave a successful demonstration of its use in computing tables in 1906.

Electromechanical calculating machine

In his work Essays on Automatics published in 1914, Leonardo Torres Quevedo wrote a brief history of Babbage's efforts at constructing a mechanical Difference Engine and Analytical Engine. The paper contains a design of a machine capable to calculate formulas like , for a sequence of sets of values. The whole machine was to be controlled by a read-only program, which was complete with provisions for conditional branching. He also introduced the idea of floating-point arithmetic.[26][27][28] In 1920, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the invention of the arithmometer, Torres presented in Paris the Electromechanical Arithmometer, which allowed a user to input arithmetic problems through a keyboard, and computed and printed the results,[29][30][31][32] demonstrating the feasibility of an electromechanical analytical engine.[33]

Analog computers

During the first half of the 20th century, many scientific computing needs were met by increasingly sophisticated analog computers, which used a direct mechanical or electrical model of the problem as a basis for computation. However, these were not programmable and generally lacked the versatility and accuracy of modern digital computers.[34] The first modern analog computer was a tide-predicting machine, invented by Sir William Thomson (later to become Lord Kelvin) in 1872. The differential analyser, a mechanical analog computer designed to solve differential equations by integration using wheel-and-disc mechanisms, was conceptualized in 1876 by James Thomson, the elder brother of the more famous Sir William Thomson.[16]

The art of mechanical analog computing reached its zenith with the differential analyzer, built by H. L. Hazen and Vannevar Bush at MIT starting in 1927. This built on the mechanical integrators of James Thomson and the torque amplifiers invented by H. W. Nieman. A dozen of these devices were built before their obsolescence became obvious. By the 1950s, the success of digital electronic computers had spelled the end for most analog computing machines, but analog computers remained in use during the 1950s in some specialized applications such as education (slide rule) and aircraft (control systems).

Digital computers

Electromechanical

Claude Shannon's 1937 master's thesis laid the foundations of digital computing, with his insight of applying Boolean algebra to the analysis and synthesis of switching circuits being the basic concept which underlies all electronic digital computers.[35][36]

By 1938, the United States Navy had developed an electromechanical analog computer small enough to use aboard a submarine. This was the Torpedo Data Computer, which used trigonometry to solve the problem of firing a torpedo at a moving target. During World War II similar devices were developed in other countries as well.

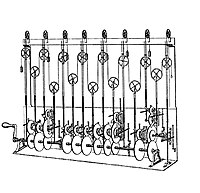

Early digital computers were electromechanical; electric switches drove mechanical relays to perform the calculation. These devices had a low operating speed and were eventually superseded by much faster all-electric computers, originally using vacuum tubes. The Z2, created by German engineer Konrad Zuse in 1939 in Berlin, was one of the earliest examples of an electromechanical relay computer.[37]

In 1941, Zuse followed his earlier machine up with the Z3, the world's first working electromechanical programmable, fully automatic digital computer.[40][41] The Z3 was built with 2000 relays, implementing a 22 bit word length that operated at a clock frequency of about 5–10 Hz.[42] Program code was supplied on punched film while data could be stored in 64 words of memory or supplied from the keyboard. It was quite similar to modern machines in some respects, pioneering numerous advances such as floating-point numbers. Rather than the harder-to-implement decimal system (used in Charles Babbage's earlier design), using a binary system meant that Zuse's machines were easier to build and potentially more reliable, given the technologies available at that time.[43] The Z3 was not itself a universal computer but could be extended to be Turing complete.[44][45]

Zuse's next computer, the Z4, became the world's first commercial computer; after initial delay due to the Second World War, it was completed in 1950 and delivered to the ETH Zurich.[46] The computer was manufactured by Zuse's own company, Zuse KG, which was founded in 1941 as the first company with the sole purpose of developing computers in Berlin.[46] The Z4 served as the inspiration for the construction of the ERMETH, the first Swiss computer and one of the first in Europe.[47]

Vacuum tubes and digital electronic circuits

Purely electronic circuit elements soon replaced their mechanical and electromechanical equivalents, at the same time that digital calculation replaced analog. The engineer Tommy Flowers, working at the Post Office Research Station in London in the 1930s, began to explore the possible use of electronics for the telephone exchange. Experimental equipment that he built in 1934 went into operation five years later, converting a portion of the telephone exchange network into an electronic data processing system, using thousands of vacuum tubes.[34] In the US, John Vincent Atanasoff and Clifford E. Berry of Iowa State University developed and tested the Atanasoff–Berry Computer (ABC) in 1942,[48] the first "automatic electronic digital computer".[49] This design was also all-electronic and used about 300 vacuum tubes, with capacitors fixed in a mechanically rotating drum for memory.[50]

During World War II, the British code-breakers at Bletchley Park achieved a number of successes at breaking encrypted German military communications. The German encryption machine, Enigma, was first attacked with the help of the electro-mechanical bombes which were often run by women.[51][52] To crack the more sophisticated German Lorenz SZ 40/42 machine, used for high-level Army communications, Max Newman and his colleagues commissioned Flowers to build the Colossus.[50] He spent eleven months from early February 1943 designing and building the first Colossus.[53] After a functional test in December 1943, Colossus was shipped to Bletchley Park, where it was delivered on 18 January 1944[54] and attacked its first message on 5 February.[50]

Colossus was the world's first electronic digital programmable computer.[34] It used a large number of valves (vacuum tubes). It had paper-tape input and was capable of being configured to perform a variety of boolean logical operations on its data, but it was not Turing-complete. Nine Mk II Colossi were built (The Mk I was converted to a Mk II making ten machines in total). Colossus Mark I contained 1,500 thermionic valves (tubes), but Mark II with 2,400 valves, was both five times faster and simpler to operate than Mark I, greatly speeding the decoding process.[55][56]

The ENIAC[57] (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was the first electronic programmable computer built in the U.S. Although the ENIAC was similar to the Colossus, it was much faster, more flexible, and it was Turing-complete. Like the Colossus, a "program" on the ENIAC was defined by the states of its patch cables and switches, a far cry from the stored program electronic machines that came later. Once a program was written, it had to be mechanically set into the machine with manual resetting of plugs and switches. The programmers of the ENIAC were six women, often known collectively as the "ENIAC girls".[58][59]

It combined the high speed of electronics with the ability to be programmed for many complex problems. It could add or subtract 5000 times a second, a thousand times faster than any other machine. It also had modules to multiply, divide, and square root. High speed memory was limited to 20 words (about 80 bytes). Built under the direction of John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert at the University of Pennsylvania, ENIAC's development and construction lasted from 1943 to full operation at the end of 1945. The machine was huge, weighing 30 tons, using 200 kilowatts of electric power and contained over 18,000 vacuum tubes, 1,500 relays, and hundreds of thousands of resistors, capacitors, and inductors.[60]

Modern computers

Concept of modern computer

The principle of the modern computer was proposed by Alan Turing in his seminal 1936 paper,[61] On Computable Numbers. Turing proposed a simple device that he called "Universal Computing machine" and that is now known as a universal Turing machine. He proved that such a machine is capable of computing anything that is computable by executing instructions (program) stored on tape, allowing the machine to be programmable. The fundamental concept of Turing's design is the stored program, where all the instructions for computing are stored in memory. Von Neumann acknowledged that the central concept of the modern computer was due to this paper.[62] Turing machines are to this day a central object of study in theory of computation. Except for the limitations imposed by their finite memory stores, modern computers are said to be Turing-complete, which is to say, they have algorithm execution capability equivalent to a universal Turing machine.

Stored programs

Early computing machines had fixed programs. Changing its function required the re-wiring and re-structuring of the machine.[50] With the proposal of the stored-program computer this changed. A stored-program computer includes by design an instruction set and can store in memory a set of instructions (a program) that details the computation. The theoretical basis for the stored-program computer was laid out by Alan Turing in his 1936 paper. In 1945, Turing joined the National Physical Laboratory and began work on developing an electronic stored-program digital computer. His 1945 report "Proposed Electronic Calculator" was the first specification for such a device. John von Neumann at the University of Pennsylvania also circulated his First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC in 1945.[34]

The Manchester Baby was the world's first stored-program computer. It was built at the University of Manchester in England by Frederic C. Williams, Tom Kilburn and Geoff Tootill, and ran its first program on 21 June 1948.[63] It was designed as a testbed for the Williams tube, the first random-access digital storage device.[64] Although the computer was described as "small and primitive" by a 1998 retrospective, it was the first working machine to contain all of the elements essential to a modern electronic computer.[65] As soon as the Baby had demonstrated the feasibility of its design, a project began at the university to develop it into a practically useful computer, the Manchester Mark 1.

The Mark 1 in turn quickly became the prototype for the Ferranti Mark 1, the world's first commercially available general-purpose computer.[66] Built by Ferranti, it was delivered to the University of Manchester in February 1951. At least seven of these later machines were delivered between 1953 and 1957, one of them to Shell labs in Amsterdam.[67] In October 1947 the directors of British catering company J. Lyons & Company decided to take an active role in promoting the commercial development of computers. Lyons's LEO I computer, modelled closely on the Cambridge EDSAC of 1949, became operational in April 1951[68] and ran the world's first routine office computer job.

Transistors

The concept of a field-effect transistor was proposed by Julius Edgar Lilienfeld in 1925. John Bardeen and Walter Brattain, while working under William Shockley at Bell Labs, built the first working transistor, the point-contact transistor, in 1947, which was followed by Shockley's bipolar junction transistor in 1948.[69][70] From 1955 onwards, transistors replaced vacuum tubes in computer designs, giving rise to the "second generation" of computers. Compared to vacuum tubes, transistors have many advantages: they are smaller, and require less power than vacuum tubes, so give off less heat. Junction transistors were much more reliable than vacuum tubes and had longer, indefinite, service life. Transistorized computers could contain tens of thousands of binary logic circuits in a relatively compact space. However, early junction transistors were relatively bulky devices that were difficult to manufacture on a mass-production basis, which limited them to a number of specialized applications.[71]

At the University of Manchester, a team under the leadership of Tom Kilburn designed and built a machine using the newly developed transistors instead of valves.[72] Their first transistorized computer and the first in the world, was operational by 1953, and a second version was completed there in April 1955. However, the machine did make use of valves to generate its 125 kHz clock waveforms and in the circuitry to read and write on its magnetic drum memory, so it was not the first completely transistorized computer. That distinction goes to the Harwell CADET of 1955,[73] built by the electronics division of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell.[73][74]

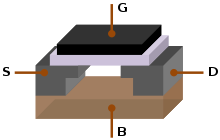

The metal–oxide–silicon field-effect transistor (MOSFET), also known as the MOS transistor, was invented at Bell Labs between 1955 and 1960[75][76][77][78][79][80] and was the first truly compact transistor that could be miniaturized and mass-produced for a wide range of uses.[71] With its high scalability,[81] and much lower power consumption and higher density than bipolar junction transistors,[82] the MOSFET made it possible to build high-density integrated circuits.[83][84] In addition to data processing, it also enabled the practical use of MOS transistors as memory cell storage elements, leading to the development of MOS semiconductor memory, which replaced earlier magnetic-core memory in computers. The MOSFET led to the microcomputer revolution,[85] and became the driving force behind the computer revolution.[86][87] The MOSFET is the most widely used transistor in computers,[88][89] and is the fundamental building block of digital electronics.[90]

Integrated circuits

The next great advance in computing power came with the advent of the integrated circuit (IC). The idea of the integrated circuit was first conceived by a radar scientist working for the Royal Radar Establishment of the Ministry of Defence, Geoffrey W.A. Dummer. Dummer presented the first public description of an integrated circuit at the Symposium on Progress in Quality Electronic Components in Washington, D.C., on 7 May 1952.[91]

The first working ICs were invented by Jack Kilby at Texas Instruments and Robert Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor.[92] Kilby recorded his initial ideas concerning the integrated circuit in July 1958, successfully demonstrating the first working integrated example on 12 September 1958.[93] In his patent application of 6 February 1959, Kilby described his new device as "a body of semiconductor material ... wherein all the components of the electronic circuit are completely integrated".[94][95] However, Kilby's invention was a hybrid integrated circuit (hybrid IC), rather than a monolithic integrated circuit (IC) chip.[96] Kilby's IC had external wire connections, which made it difficult to mass-produce.[97]

Noyce also came up with his own idea of an integrated circuit half a year later than Kilby.[98] Noyce's invention was the first true monolithic IC chip.[99][97] His chip solved many practical problems that Kilby's had not. Produced at Fairchild Semiconductor, it was made of silicon, whereas Kilby's chip was made of germanium. Noyce's monolithic IC was fabricated using the planar process, developed by his colleague Jean Hoerni in early 1959. In turn, the planar process was based on Carl Frosch and Lincoln Derick work on semiconductor surface passivation by silicon dioxide.[100][101][102][103][104][105]

Modern monolithic ICs are predominantly MOS (metal–oxide–semiconductor) integrated circuits, built from MOSFETs (MOS transistors).[106] The earliest experimental MOS IC to be fabricated was a 16-transistor chip built by Fred Heiman and Steven Hofstein at RCA in 1962.[107] General Microelectronics later introduced the first commercial MOS IC in 1964,[108] developed by Robert Norman.[107] Following the development of the self-aligned gate (silicon-gate) MOS transistor by Robert Kerwin, Donald Klein and John Sarace at Bell Labs in 1967, the first silicon-gate MOS IC with self-aligned gates was developed by Federico Faggin at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1968.[109] The MOSFET has since become the most critical device component in modern ICs.[106]

The development of the MOS integrated circuit led to the invention of the microprocessor,[110][111] and heralded an explosion in the commercial and personal use of computers. While the subject of exactly which device was the first microprocessor is contentious, partly due to lack of agreement on the exact definition of the term "microprocessor", it is largely undisputed that the first single-chip microprocessor was the Intel 4004,[112] designed and realized by Federico Faggin with his silicon-gate MOS IC technology,[110] along with Ted Hoff, Masatoshi Shima and Stanley Mazor at Intel.[b][114] In the early 1970s, MOS IC technology enabled the integration of more than 10,000 transistors on a single chip.[84]

System on a Chip (SoCs) are complete computers on a microchip (or chip) the size of a coin.[115] They may or may not have integrated RAM and flash memory. If not integrated, the RAM is usually placed directly above (known as Package on package) or below (on the opposite side of the circuit board) the SoC, and the flash memory is usually placed right next to the SoC. This is done to improve data transfer speeds, as the data signals do not have to travel long distances. Since ENIAC in 1945, computers have advanced enormously, with modern SoCs (such as the Snapdragon 865) being the size of a coin while also being hundreds of thousands of times more powerful than ENIAC, integrating billions of transistors, and consuming only a few watts of power.

Mobile computers

The first mobile computers were heavy and ran from mains power. The 50 lb (23 kg) IBM 5100 was an early example. Later portables such as the Osborne 1 and Compaq Portable were considerably lighter but still needed to be plugged in. The first laptops, such as the Grid Compass, removed this requirement by incorporating batteries – and with the continued miniaturization of computing resources and advancements in portable battery life, portable computers grew in popularity in the 2000s.[116] The same developments allowed manufacturers to integrate computing resources into cellular mobile phones by the early 2000s.

These smartphones and tablets run on a variety of operating systems and recently became the dominant computing device on the market.[117] These are powered by System on a Chip (SoCs), which are complete computers on a microchip the size of a coin.[115]

Types

Computers can be classified in a number of different ways, including:

By architecture

- Analog computer

- Digital computer

- Hybrid computer

- Harvard architecture

- Von Neumann architecture

- Complex instruction set computer

- Reduced instruction set computer

By size, form-factor and purpose

- Supercomputer

- Mainframe computer

- Minicomputer (term no longer used),[118] Midrange computer

- Server

- Personal computer

- Workstation

- Microcomputer (term no longer used)[119]

- Home computer (term fallen into disuse)[120]

- Desktop computer

- Tower desktop

- Slimline desktop

- Multimedia computer (non-linear editing system computers, video editing PCs and the like, this term is no longer used)[121]

- Gaming computer

- All-in-one PC

- Nettop (Small form factor PCs, Mini PCs)

- Home theater PC

- Keyboard computer

- Portable computer

- Thin client

- Internet appliance

- Laptop computer

- Mobile computer

- Wearable computer

- Single-board computer

- Plug computer

- Stick PC

- Programmable logic controller

- Computer-on-module

- System on module

- System in a package

- System-on-chip (Also known as an Application Processor or AP if it lacks circuitry such as radio circuitry)

- Microcontroller

Hardware

The term hardware covers all of those parts of a computer that are tangible physical objects. Circuits, computer chips, graphic cards, sound cards, memory (RAM), motherboard, displays, power supplies, cables, keyboards, printers and "mice" input devices are all hardware.

History of computing hardware

Other hardware topics

| Peripheral device (input/output) | Input | Mouse, keyboard, joystick, image scanner, webcam, graphics tablet, microphone |

| Output | Monitor, printer, loudspeaker | |

| Both | Floppy disk drive, hard disk drive, optical disc drive, teleprinter | |

| Computer buses | Short range | RS-232, SCSI, PCI, USB |

| Long range (computer networking) | Ethernet, ATM, FDDI |

A general-purpose computer has four main components: the arithmetic logic unit (ALU), the control unit, the memory, and the input and output devices (collectively termed I/O). These parts are interconnected by buses, often made of groups of wires. Inside each of these parts are thousands to trillions of small electrical circuits which can be turned off or on by means of an electronic switch. Each circuit represents a bit (binary digit) of information so that when the circuit is on it represents a "1", and when off it represents a "0" (in positive logic representation). The circuits are arranged in logic gates so that one or more of the circuits may control the state of one or more of the other circuits.

Input devices

When unprocessed data is sent to the computer with the help of input devices, the data is processed and sent to output devices. The input devices may be hand-operated or automated. The act of processing is mainly regulated by the CPU. Some examples of input devices are:

- Computer keyboard

- Digital camera

- Graphics tablet

- Image scanner

- Joystick

- Microphone

- Mouse

- Overlay keyboard

- Real-time clock

- Trackball

- Touchscreen

- Light pen

Output devices

The means through which computer gives output are known as output devices. Some examples of output devices are:

Control unit

The control unit (often called a control system or central controller) manages the computer's various components; it reads and interprets (decodes) the program instructions, transforming them into control signals that activate other parts of the computer.[d] Control systems in advanced computers may change the order of execution of some instructions to improve performance.

A key component common to all CPUs is the program counter, a special memory cell (a register) that keeps track of which location in memory the next instruction is to be read from.[e]

The control system's function is as follows— this is a simplified description, and some of these steps may be performed concurrently or in a different order depending on the type of CPU:

- Read the code for the next instruction from the cell indicated by the program counter.

- Decode the numerical code for the instruction into a set of commands or signals for each of the other systems.

- Increment the program counter so it points to the next instruction.

- Read whatever data the instruction requires from cells in memory (or perhaps from an input device). The location of this required data is typically stored within the instruction code.

- Provide the necessary data to an ALU or register.

- If the instruction requires an ALU or specialized hardware to complete, instruct the hardware to perform the requested operation.

- Write the result from the ALU back to a memory location or to a register or perhaps an output device.

- Jump back to step (1).

Since the program counter is (conceptually) just another set of memory cells, it can be changed by calculations done in the ALU. Adding 100 to the program counter would cause the next instruction to be read from a place 100 locations further down the program. Instructions that modify the program counter are often known as "jumps" and allow for loops (instructions that are repeated by the computer) and often conditional instruction execution (both examples of control flow).

The sequence of operations that the control unit goes through to process an instruction is in itself like a short computer program, and indeed, in some more complex CPU designs, there is another yet smaller computer called a microsequencer, which runs a microcode program that causes all of these events to happen.

Central processing unit (CPU)

The control unit, ALU, and registers are collectively known as a central processing unit (CPU). Early CPUs were composed of many separate components. Since the 1970s, CPUs have typically been constructed on a single MOS integrated circuit chip called a microprocessor.

Arithmetic logic unit (ALU)

The ALU is capable of performing two classes of operations: arithmetic and logic.[122] The set of arithmetic operations that a particular ALU supports may be limited to addition and subtraction, or might include multiplication, division, trigonometry functions such as sine, cosine, etc., and square roots. Some can operate only on whole numbers (integers) while others use floating point to represent real numbers, albeit with limited precision. However, any computer that is capable of performing just the simplest operations can be programmed to break down the more complex operations into simple steps that it can perform. Therefore, any computer can be programmed to perform any arithmetic operation—although it will take more time to do so if its ALU does not directly support the operation. An ALU may also compare numbers and return Boolean truth values (true or false) depending on whether one is equal to, greater than or less than the other ("is 64 greater than 65?"). Logic operations involve Boolean logic: AND, OR, XOR, and NOT. These can be useful for creating complicated conditional statements and processing Boolean logic.

Superscalar computers may contain multiple ALUs, allowing them to process several instructions simultaneously.[123] Graphics processors and computers with SIMD and MIMD features often contain ALUs that can perform arithmetic on vectors and matrices.

Memory

A computer's memory can be viewed as a list of cells into which numbers can be placed or read. Each cell has a numbered "address" and can store a single number. The computer can be instructed to "put the number 123 into the cell numbered 1357" or to "add the number that is in cell 1357 to the number that is in cell 2468 and put the answer into cell 1595." The information stored in memory may represent practically anything. Letters, numbers, even computer instructions can be placed into memory with equal ease. Since the CPU does not differentiate between different types of information, it is the software's responsibility to give significance to what the memory sees as nothing but a series of numbers.

In almost all modern computers, each memory cell is set up to store binary numbers in groups of eight bits (called a byte). Each byte is able to represent 256 different numbers (28 = 256); either from 0 to 255 or −128 to +127. To store larger numbers, several consecutive bytes may be used (typically, two, four or eight). When negative numbers are required, they are usually stored in two's complement notation. Other arrangements are possible, but are usually not seen outside of specialized applications or historical contexts. A computer can store any kind of information in memory if it can be represented numerically. Modern computers have billions or even trillions of bytes of memory.

The CPU contains a special set of memory cells called registers that can be read and written to much more rapidly than the main memory area. There are typically between two and one hundred registers depending on the type of CPU. Registers are used for the most frequently needed data items to avoid having to access main memory every time data is needed. As data is constantly being worked on, reducing the need to access main memory (which is often slow compared to the ALU and control units) greatly increases the computer's speed.

Computer main memory comes in two principal varieties:

- random-access memory or RAM

- read-only memory or ROM

RAM can be read and written to anytime the CPU commands it, but ROM is preloaded with data and software that never changes, therefore the CPU can only read from it. ROM is typically used to store the computer's initial start-up instructions. In general, the contents of RAM are erased when the power to the computer is turned off, but ROM retains its data indefinitely. In a PC, the ROM contains a specialized program called the BIOS that orchestrates loading the computer's operating system from the hard disk drive into RAM whenever the computer is turned on or reset. In embedded computers, which frequently do not have disk drives, all of the required software may be stored in ROM. Software stored in ROM is often called firmware, because it is notionally more like hardware than software. Flash memory blurs the distinction between ROM and RAM, as it retains its data when turned off but is also rewritable. It is typically much slower than conventional ROM and RAM however, so its use is restricted to applications where high speed is unnecessary.[f]

In more sophisticated computers there may be one or more RAM cache memories, which are slower than registers but faster than main memory. Generally computers with this sort of cache are designed to move frequently needed data into the cache automatically, often without the need for any intervention on the programmer's part.

Input/output (I/O)

I/O is the means by which a computer exchanges information with the outside world.[125] Devices that provide input or output to the computer are called peripherals.[126] On a typical personal computer, peripherals include input devices like the keyboard and mouse, and output devices such as the display and printer. Hard disk drives, floppy disk drives and optical disc drives serve as both input and output devices. Computer networking is another form of I/O. I/O devices are often complex computers in their own right, with their own CPU and memory. A graphics processing unit might contain fifty or more tiny computers that perform the calculations necessary to display 3D graphics.[citation needed] Modern desktop computers contain many smaller computers that assist the main CPU in performing I/O. A 2016-era flat screen display contains its own computer circuitry.

Multitasking

While a computer may be viewed as running one gigantic program stored in its main memory, in some systems it is necessary to give the appearance of running several programs simultaneously. This is achieved by multitasking i.e. having the computer switch rapidly between running each program in turn.[127] One means by which this is done is with a special signal called an interrupt, which can periodically cause the computer to stop executing instructions where it was and do something else instead. By remembering where it was executing prior to the interrupt, the computer can return to that task later. If several programs are running "at the same time". then the interrupt generator might be causing several hundred interrupts per second, causing a program switch each time. Since modern computers typically execute instructions several orders of magnitude faster than human perception, it may appear that many programs are running at the same time even though only one is ever executing in any given instant. This method of multitasking is sometimes termed "time-sharing" since each program is allocated a "slice" of time in turn.[128]

Before the era of inexpensive computers, the principal use for multitasking was to allow many people to share the same computer. Seemingly, multitasking would cause a computer that is switching between several programs to run more slowly, in direct proportion to the number of programs it is running, but most programs spend much of their time waiting for slow input/output devices to complete their tasks. If a program is waiting for the user to click on the mouse or press a key on the keyboard, then it will not take a "time slice" until the event it is waiting for has occurred. This frees up time for other programs to execute so that many programs may be run simultaneously without unacceptable speed loss.

Multiprocessing

Some computers are designed to distribute their work across several CPUs in a multiprocessing configuration, a technique once employed in only large and powerful machines such as supercomputers, mainframe computers and servers. Multiprocessor and multi-core (multiple CPUs on a single integrated circuit) personal and laptop computers are now widely available, and are being increasingly used in lower-end markets as a result.

Supercomputers in particular often have highly unique architectures that differ significantly from the basic stored-program architecture and from general-purpose computers.[g] They often feature thousands of CPUs, customized high-speed interconnects, and specialized computing hardware. Such designs tend to be useful for only specialized tasks due to the large scale of program organization required to use most of the available resources at once. Supercomputers usually see usage in large-scale simulation, graphics rendering, and cryptography applications, as well as with other so-called "embarrassingly parallel" tasks.

Software

Software refers to parts of the computer which do not have a material form, such as programs, data, protocols, etc. Software is that part of a computer system that consists of encoded information or computer instructions, in contrast to the physical hardware from which the system is built. Computer software includes computer programs, libraries and related non-executable data, such as online documentation or digital media. It is often divided into system software and application software. Computer hardware and software require each other and neither can be realistically used on its own. When software is stored in hardware that cannot easily be modified, such as with BIOS ROM in an IBM PC compatible computer, it is sometimes called "firmware".

Languages

There are thousands of different programming languages—some intended for general purpose, others useful for only highly specialized applications.

| Lists of programming languages | Timeline of programming languages, List of programming languages by category, Generational list of programming languages, List of programming languages, Non-English-based programming languages |

| Commonly used assembly languages | ARM, MIPS, x86 |

| Commonly used high-level programming languages | Ada, BASIC, C, C++, C#, COBOL, Fortran, PL/I, REXX, Java, Lisp, Pascal, Object Pascal |

| Commonly used scripting languages | Bourne script, JavaScript, Python, Ruby, PHP, Perl |

Programs

The defining feature of modern computers which distinguishes them from all other machines is that they can be programmed. That is to say that some type of instructions (the program) can be given to the computer, and it will process them. Modern computers based on the von Neumann architecture often have machine code in the form of an imperative programming language. In practical terms, a computer program may be just a few instructions or extend to many millions of instructions, as do the programs for word processors and web browsers for example. A typical modern computer can execute billions of instructions per second (gigaflops) and rarely makes a mistake over many years of operation. Large computer programs consisting of several million instructions may take teams of programmers years to write, and due to the complexity of the task almost certainly contain errors.

Stored program architecture

This section applies to most common RAM machine–based computers.

In most cases, computer instructions are simple: add one number to another, move some data from one location to another, send a message to some external device, etc. These instructions are read from the computer's memory and are generally carried out (executed) in the order they were given. However, there are usually specialized instructions to tell the computer to jump ahead or backwards to some other place in the program and to carry on executing from there. These are called "jump" instructions (or branches). Furthermore, jump instructions may be made to happen conditionally so that different sequences of instructions may be used depending on the result of some previous calculation or some external event. Many computers directly support subroutines by providing a type of jump that "remembers" the location it jumped from and another instruction to return to the instruction following that jump instruction.

Program execution might be likened to reading a book. While a person will normally read each word and line in sequence, they may at times jump back to an earlier place in the text or skip sections that are not of interest. Similarly, a computer may sometimes go back and repeat the instructions in some section of the program over and over again until some internal condition is met. This is called the flow of control within the program and it is what allows the computer to perform tasks repeatedly without human intervention.

Comparatively, a person using a pocket calculator can perform a basic arithmetic operation such as adding two numbers with just a few button presses. But to add together all of the numbers from 1 to 1,000 would take thousands of button presses and a lot of time, with a near certainty of making a mistake. On the other hand, a computer may be programmed to do this with just a few simple instructions. The following example is written in the MIPS assembly language:

begin:

addi $8, $0, 0 # initialize sum to 0

addi $9, $0, 1 # set first number to add = 1

loop:

slti $10, $9, 1000 # check if the number is less than 1000

beq $10, $0, finish # if odd number is greater than n then exit

add $8, $8, $9 # update sum

addi $9, $9, 1 # get next number

j loop # repeat the summing process

finish:

add $2, $8, $0 # put sum in output register

Once told to run this program, the computer will perform the repetitive addition task without further human intervention. It will almost never make a mistake and a modern PC can complete the task in a fraction of a second.

Machine code

In most computers, individual instructions are stored as machine code with each instruction being given a unique number (its operation code or opcode for short). The command to add two numbers together would have one opcode; the command to multiply them would have a different opcode, and so on. The simplest computers are able to perform any of a handful of different instructions; the more complex computers have several hundred to choose from, each with a unique numerical code. Since the computer's memory is able to store numbers, it can also store the instruction codes. This leads to the important fact that entire programs (which are just lists of these instructions) can be represented as lists of numbers and can themselves be manipulated inside the computer in the same way as numeric data. The fundamental concept of storing programs in the computer's memory alongside the data they operate on is the crux of the von Neumann, or stored program, architecture.[130][131] In some cases, a computer might store some or all of its program in memory that is kept separate from the data it operates on. This is called the Harvard architecture after the Harvard Mark I computer. Modern von Neumann computers display some traits of the Harvard architecture in their designs, such as in CPU caches.

While it is possible to write computer programs as long lists of numbers (machine language) and while this technique was used with many early computers,[h] it is extremely tedious and potentially error-prone to do so in practice, especially for complicated programs. Instead, each basic instruction can be given a short name that is indicative of its function and easy to remember – a mnemonic such as ADD, SUB, MULT or JUMP. These mnemonics are collectively known as a computer's assembly language. Converting programs written in assembly language into something the computer can actually understand (machine language) is usually done by a computer program called an assembler.

Programming language

Programming languages provide various ways of specifying programs for computers to run. Unlike natural languages, programming languages are designed to permit no ambiguity and to be concise. They are purely written languages and are often difficult to read aloud. They are generally either translated into machine code by a compiler or an assembler before being run, or translated directly at run time by an interpreter. Sometimes programs are executed by a hybrid method of the two techniques.

Low-level languages

Machine languages and the assembly languages that represent them (collectively termed low-level programming languages) are generally unique to the particular architecture of a computer's central processing unit (CPU). For instance, an ARM architecture CPU (such as may be found in a smartphone or a hand-held videogame) cannot understand the machine language of an x86 CPU that might be in a PC.[i] Historically a significant number of other CPU architectures were created and saw extensive use, notably including the MOS Technology 6502 and 6510 in addition to the Zilog Z80.

High-level languages

Although considerably easier than in machine language, writing long programs in assembly language is often difficult and is also error prone. Therefore, most practical programs are written in more abstract high-level programming languages that are able to express the needs of the programmer more conveniently (and thereby help reduce programmer error). High level languages are usually "compiled" into machine language (or sometimes into assembly language and then into machine language) using another computer program called a compiler.[j] High level languages are less related to the workings of the target computer than assembly language, and more related to the language and structure of the problem(s) to be solved by the final program. It is therefore often possible to use different compilers to translate the same high level language program into the machine language of many different types of computer. This is part of the means by which software like video games may be made available for different computer architectures such as personal computers and various video game consoles.

Program design

Program design of small programs is relatively simple and involves the analysis of the problem, collection of inputs, using the programming constructs within languages, devising or using established procedures and algorithms, providing data for output devices and solutions to the problem as applicable.[132] As problems become larger and more complex, features such as subprograms, modules, formal documentation, and new paradigms such as object-oriented programming are encountered.[133] Large programs involving thousands of line of code and more require formal software methodologies.[134] The task of developing large software systems presents a significant intellectual challenge.[135] Producing software with an acceptably high reliability within a predictable schedule and budget has historically been difficult;[136] the academic and professional discipline of software engineering concentrates specifically on this challenge.[137]

Bugs

Errors in computer programs are called "bugs". They may be benign and not affect the usefulness of the program, or have only subtle effects. However, in some cases they may cause the program or the entire system to "hang", becoming unresponsive to input such as mouse clicks or keystrokes, to completely fail, or to crash.[138] Otherwise benign bugs may sometimes be harnessed for malicious intent by an unscrupulous user writing an exploit, code designed to take advantage of a bug and disrupt a computer's proper execution. Bugs are usually not the fault of the computer. Since computers merely execute the instructions they are given, bugs are nearly always the result of programmer error or an oversight made in the program's design.[k] Admiral Grace Hopper, an American computer scientist and developer of the first compiler, is credited for having first used the term "bugs" in computing after a dead moth was found shorting a relay in the Harvard Mark II computer in September 1947.[139]

Networking and the Internet

Computers have been used to coordinate information between multiple physical locations since the 1950s. The U.S. military's SAGE system was the first large-scale example of such a system, which led to a number of special-purpose commercial systems such as Sabre.[140]

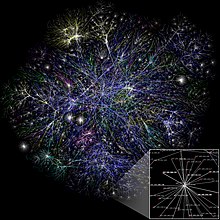

In the 1970s, computer engineers at research institutions throughout the United States began to link their computers together using telecommunications technology. The effort was funded by ARPA (now DARPA), and the computer network that resulted was called the ARPANET.[141] The technologies that made the Arpanet possible spread and evolved. In time, the network spread beyond academic and military institutions and became known as the Internet.

The emergence of networking involved a redefinition of the nature and boundaries of computers. Computer operating systems and applications were modified to include the ability to define and access the resources of other computers on the network, such as peripheral devices, stored information, and the like, as extensions of the resources of an individual computer. Initially these facilities were available primarily to people working in high-tech environments, but in the 1990s, computer networking become almost ubiquitous, due to the spread of applications like e-mail and the World Wide Web, combined with the development of cheap, fast networking technologies like Ethernet and ADSL.

The number of computers that are networked is growing phenomenally. A very large proportion of personal computers regularly connect to the Internet to communicate and receive information. "Wireless" networking, often utilizing mobile phone networks, has meant networking is becoming increasingly ubiquitous even in mobile computing environments.

Unconventional computers

A computer does not need to be electronic, nor even have a processor, nor RAM, nor even a hard disk. While popular usage of the word "computer" is synonymous with a personal electronic computer,[l] a typical modern definition of a computer is: "A device that computes, especially a programmable [usually] electronic machine that performs high-speed mathematical or logical operations or that assembles, stores, correlates, or otherwise processes information."[142] According to this definition, any device that processes information qualifies as a computer.

Future

There is active research to make unconventional computers out of many promising new types of technology, such as optical computers, DNA computers, neural computers, and quantum computers. Most computers are universal, and are able to calculate any computable function, and are limited only by their memory capacity and operating speed. However different designs of computers can give very different performance for particular problems; for example quantum computers can potentially break some modern encryption algorithms (by quantum factoring) very quickly.

Computer architecture paradigms

There are many types of computer architectures:

- Quantum computer vs. Chemical computer

- Scalar processor vs. Vector processor

- Non-Uniform Memory Access (NUMA) computers

- Register machine vs. Stack machine

- Harvard architecture vs. von Neumann architecture

- Cellular architecture

Of all these abstract machines, a quantum computer holds the most promise for revolutionizing computing.[143] Logic gates are a common abstraction which can apply to most of the above digital or analog paradigms. The ability to store and execute lists of instructions called programs makes computers extremely versatile, distinguishing them from calculators. The Church–Turing thesis is a mathematical statement of this versatility: any computer with a minimum capability (being Turing-complete) is, in principle, capable of performing the same tasks that any other computer can perform. Therefore, any type of computer (netbook, supercomputer, cellular automaton, etc.) is able to perform the same computational tasks, given enough time and storage capacity.

Artificial intelligence

A computer will solve problems in exactly the way it is programmed to, without regard to efficiency, alternative solutions, possible shortcuts, or possible errors in the code. Computer programs that learn and adapt are part of the emerging field of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Artificial intelligence based products generally fall into two major categories: rule-based systems and pattern recognition systems. Rule-based systems attempt to represent the rules used by human experts and tend to be expensive to develop. Pattern-based systems use data about a problem to generate conclusions. Examples of pattern-based systems include voice recognition, font recognition, translation and the emerging field of on-line marketing.

Professions and organizations

As the use of computers has spread throughout society, there are an increasing number of careers involving computers.

| Hardware-related | Electrical engineering, Electronic engineering, Computer engineering, Telecommunications engineering, Optical engineering, Nanoengineering |

| Software-related | Computer science, Computer engineering, Desktop publishing, Human–computer interaction, Information technology, Information systems, Computational science, Software engineering, Video game industry, Web design |

The need for computers to work well together and to be able to exchange information has spawned the need for many standards organizations, clubs and societies of both a formal and informal nature.

| Standards groups | ANSI, IEC, IEEE, IETF, ISO, W3C |

| Professional societies | ACM, AIS, IET, IFIP, BCS |

| Free/open source software groups | Free Software Foundation, Mozilla Foundation, Apache Software Foundation |

See also

- Computability theory

- Computer security

- Glossary of computer hardware terms

- History of computer science

- List of computer term etymologies

- List of computer system manufacturers

- List of fictional computers

- List of films about computers

- List of pioneers in computer science

- Outline of computers

- Pulse computation

- TOP500 (list of most powerful computers)

- Unconventional computing

Notes

- ^ According to Schmandt-Besserat 1981, these clay containers contained tokens, the total of which were the count of objects being transferred. The containers thus served as something of a bill of lading or an accounts book. In order to avoid breaking open the containers, first, clay impressions of the tokens were placed on the outside of the containers, for the count; the shapes of the impressions were abstracted into stylized marks; finally, the abstract marks were systematically used as numerals; these numerals were finally formalized as numbers.

Eventually the marks on the outside of the containers were all that were needed to convey the count, and the clay containers evolved into clay tablets with marks for the count. Schmandt-Besserat 1999 estimates it took 4000 years. - ^ The Intel 4004 (1971) die was 12 mm2, composed of 2300 transistors; by comparison, the Pentium Pro was 306 mm2, composed of 5.5 million transistors.[113]

- ^ Most major 64-bit instruction set architectures are extensions of earlier designs. All of the architectures listed in this table, except for Alpha, existed in 32-bit forms before their 64-bit incarnations were introduced.

- ^ The control unit's role in interpreting instructions has varied somewhat in the past. Although the control unit is solely responsible for instruction interpretation in most modern computers, this is not always the case. Some computers have instructions that are partially interpreted by the control unit with further interpretation performed by another device. For example, EDVAC, one of the earliest stored-program computers, used a central control unit that interpreted only four instructions. All of the arithmetic-related instructions were passed on to its arithmetic unit and further decoded there.

- ^ Instructions often occupy more than one memory address, therefore the program counter usually increases by the number of memory locations required to store one instruction.

- ^ Flash memory also may only be rewritten a limited number of times before wearing out, making it less useful for heavy random access usage.[124]

- ^ However, it is also very common to construct supercomputers out of many pieces of cheap commodity hardware; usually individual computers connected by networks. These so-called computer clusters can often provide supercomputer performance at a much lower cost than customized designs. While custom architectures are still used for most of the most powerful supercomputers, there has been a proliferation of cluster computers in recent years.[129]

- ^ Even some later computers were commonly programmed directly in machine code. Some minicomputers like the DEC PDP-8 could be programmed directly from a panel of switches. However, this method was usually used only as part of the booting process. Most modern computers boot entirely automatically by reading a boot program from some non-volatile memory.

- ^ However, there is sometimes some form of machine language compatibility between different computers. An x86-64 compatible microprocessor like the AMD Athlon 64 is able to run most of the same programs that an Intel Core 2 microprocessor can, as well as programs designed for earlier microprocessors like the Intel Pentiums and Intel 80486. This contrasts with very early commercial computers, which were often one-of-a-kind and totally incompatible with other computers.

- ^ High level languages are also often interpreted rather than compiled. Interpreted languages are translated into machine code on the fly, while running, by another program called an interpreter.

- ^ It is not universally true that bugs are solely due to programmer oversight. Computer hardware may fail or may itself have a fundamental problem that produces unexpected results in certain situations. For instance, the Pentium FDIV bug caused some Intel microprocessors in the early 1990s to produce inaccurate results for certain floating point division operations. This was caused by a flaw in the microprocessor design and resulted in a partial recall of the affected devices.

- ^ According to the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (6th ed, 2007), the word computer dates back to the mid 17th century, when it referred to "A person who makes calculations; specifically a person employed for this in an observatory etc."

References

- ^ Evans 2018, p. 23.

- ^ Smith 2013, p. 6.

- ^ "computer (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Robson, Eleanor (2008). Mathematics in Ancient Iraq. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-691-09182-2.: calculi were in use in Iraq for primitive accounting systems as early as 3200–3000 BCE, with commodity-specific counting representation systems. Balanced accounting was in use by 3000–2350 BCE, and a sexagesimal number system was in use 2350–2000 BCE.

- ^ Flegg, Graham. (1989). Numbers through the ages. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Education. ISBN 0-333-49130-0. OCLC 24660570.

- ^ The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project Archived 28 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- ^ Marchant, Jo (1 November 2006). "In search of lost time". Nature. 444 (7119): 534–538. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..534M. doi:10.1038/444534a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 17136067. S2CID 4305761.

- ^ G. Wiet, V. Elisseeff, P. Wolff, J. Naudu (1975). History of Mankind, Vol 3: The Great medieval Civilisations, p. 649. George Allen & Unwin Limited, UNESCO.

- ^ Fuat Sezgin. "Catalogue of the Exhibition of the Institute for the History of Arabic-Islamic Science (at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University", Frankfurt, Germany), Frankfurt Book Fair 2004, pp. 35 & 38.

- ^ Charette, François (2006). "Archaeology: High tech from Ancient Greece". Nature. 444 (7119): 551–552. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..551C. doi:10.1038/444551a. PMID 17136077. S2CID 33513516.

- ^ Bedini, Silvio A.; Maddison, Francis R. (1966). "Mechanical Universe: The Astrarium of Giovanni de' Dondi". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 56 (5): 1–69. doi:10.2307/1006002. JSTOR 1006002.

- ^ Price, Derek de S. (1984). "A History of Calculating Machines". IEEE Micro. 4 (1): 22–52. doi:10.1109/MM.1984.291305.

- ^ Őren, Tuncer (2001). "Advances in Computer and Information Sciences: From Abacus to Holonic Agents" (PDF). Turk J Elec Engin. 9 (1): 63–70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ^ Donald Routledge Hill (1985). "Al-Biruni's mechanical calendar", Annals of Science 42, pp. 139–163.

- ^ "The Writer Automaton, Switzerland". chonday.com. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ a b Ray Girvan, "The revealed grace of the mechanism: computing after Babbage", Archived 3 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Scientific Computing World, May/June 2003.

- ^ Torres, Leonardo (10 October 1895). "Memória sobre las Máquinas Algébricas" (PDF). Revista de Obras Públicas (in Spanish) (28): 217–222.

- ^ Leonardo Torres. Memoria sobre las máquinas algébricas: con un informe de la Real academia de ciencias exactas, fisicas y naturales, Misericordia, 1895.

- ^ Thomas, Federico (1 August 2008). "A short account on Leonardo Torres' endless spindle". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 43 (8). IFToMM: 1055–1063. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2007.07.003. hdl:10261/30460. ISSN 0094-114X.

- ^ Gomez-Jauregui, Valentin; Gutierrez-Garcia, Andres; González-Redondo, Francisco A.; Iglesias, Miguel; Manchado, Cristina; Otero, Cesar (1 June 2022). "Torres Quevedo's mechanical calculator for second-degree equations with complex coefficients". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 172 (8). IFToMM: 104830. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2022.104830. hdl:10902/24391. S2CID 247503677.

- ^ Torres Quevedo, Leonardo (1901). "Machines á calculer". Mémoires Présentés par Divers Savants à l'Académie des Scienes de l'Institut de France (in French). XXXII. Impr. nationale (París).

- ^ Halacy, Daniel Stephen (1970). Charles Babbage, Father of the Computer. Crowell-Collier Press. ISBN 978-0-02-741370-0.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (1998). "Charles Babbage". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- ^ "Babbage". Online stuff. Science Museum. 19 January 2007. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Graham-Cumming, John (23 December 2010). "Let's build Babbage's ultimate mechanical computer". opinion. New Scientist. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ L. Torres Quevedo. Ensayos sobre Automática – Su definicion. Extension teórica de sus aplicaciones, Revista de la Academia de Ciencias Exacta, Revista 12, pp. 391–418, 1914.

- ^ Torres Quevedo, Leonardo. Automática: Complemento de la Teoría de las Máquinas, (pdf), pp. 575–583, Revista de Obras Públicas, 19 November 1914.

- ^ Ronald T. Kneusel. Numbers and Computers, Springer, pp. 84–85, 2017. ISBN 978-3-319-50508-4

- ^ Randell 1982, p. 6, 11–13.

- ^ B. Randell. Electromechanical Calculating Machine, The Origins of Digital Computers, pp.109–120, 1982.

- ^ Bromley 1990.

- ^ Cristopher Moore, Stephan Mertens. The Nature of Computation, Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, p. 291, 2011. ISBN 978-0-199-23321-2.

- ^ Randell, Brian. Digital Computers, History of Origins, (pdf), p. 545, Digital Computers: Origins, Encyclopedia of Computer Science, January 2003.

- ^ a b c d The Modern History of Computing. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2017. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ O’Regan, Gerard, ed. (2008). A Brief History of Computing. London: Springer London. p. 28. doi:10.1007/978-1-84800-084-1. ISBN 978-1-84800-083-4.

- ^ Tse, David (22 December 2020). "How Claude Shannon Invented the Future". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved 5 November 2024.

- ^ Zuse, Horst. "Part 4: Konrad Zuse's Z1 and Z3 Computers". The Life and Work of Konrad Zuse. EPE Online. Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ Bellis, Mary (15 May 2019) [First published 2006 at inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aa050298.htm]. "Biography of Konrad Zuse, Inventor and Programmer of Early Computers". thoughtco.com. Dotdash Meredith. Archived from the original on 13 December 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

Konrad Zuse earned the semiofficial title of 'inventor of the modern computer'[who?].

- ^ "Who is the Father of the Computer?". ComputerHope.

- ^ Zuse, Konrad (2010) [1984]. The Computer – My Life Translated by McKenna, Patricia and Ross, J. Andrew from: Der Computer, mein Lebenswerk (1984). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-08151-4.

- ^ Salz Trautman, Peggy (20 April 1994). "A Computer Pioneer Rediscovered, 50 Years On". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Zuse, Konrad (1993). Der Computer. Mein Lebenswerk (in German) (3rd ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-540-56292-4.

- ^ "Crash! The Story of IT: Zuse". Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ Rojas, R. (1998). "How to make Zuse's Z3 a universal computer". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 20 (3): 51–54. doi:10.1109/85.707574. S2CID 14606587.

- ^ Rojas, Raúl. "How to Make Zuse's Z3 a Universal Computer" (PDF). fu-berlin.de. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ a b O'Regan, Gerard (2010). A Brief History of Computing. Springer Nature. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-030-66599-9.

- ^ Bruderer, Herbert (2021). Milestones in Analog and Digital Computing (3rd ed.). Springer. pp. 1009, 1087. ISBN 978-3-03040973-9.

- ^ "notice". Des Moines Register. 15 January 1941.

- ^ Arthur W. Burks (1989). The First Electronic Computer. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08104-7. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d Copeland, Jack (2006). Colossus: The Secrets of Bletchley Park's Codebreaking Computers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 101–115. ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4.

- ^ Miller, Joe (10 November 2014). "The woman who cracked Enigma cyphers". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Bearne, Suzanne (24 July 2018). "Meet the female codebreakers of Bletchley Park". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ "Bletchley's code-cracking Colossus". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Colossus – The Rebuild Story". The National Museum of Computing. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Randell, Brian; Fensom, Harry; Milne, Frank A. (15 March 1995). "Obituary: Allen Coombs". The Independent. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ Fensom, Jim (8 November 2010). "Harry Fensom obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 September 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ John Presper Eckert Jr. and John W. Mauchly, Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, United States Patent Office, US Patent 3,120,606, filed 26 June 1947, issued 4 February 1964, and invalidated 19 October 1973 after court ruling on Honeywell v. Sperry Rand.

- ^ Evans 2018, p. 39.

- ^ Light 1999, p. 459.

- ^ "Generations of Computer". techiwarehouse.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Turing, A. M. (1937). "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society. 2. 42 (1): 230–265. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230. S2CID 73712.

- ^ Copeland, Jack (2004). The Essential Turing. p. 22:

von Neumann ... firmly emphasized to me, and to others I am sure, that the fundamental conception is owing to Turing—insofar as not anticipated by Babbage, Lovelace and others.

Letter by Stanley Frankel to Brian Randell, 1972. - ^ Enticknap, Nicholas (Summer 1998). "Computing's Golden Jubilee". Resurrection (20). ISSN 0958-7403. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ "Early computers at Manchester University". Resurrection. 1 (4). Summer 1992. ISSN 0958-7403. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ "Early Electronic Computers (1946–51)". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ^ Napper, R. B. E. "Introduction to the Mark 1". The University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2008.

- ^ "Our Computer Heritage Pilot Study: Deliveries of Ferranti Mark I and Mark I Star computers". Computer Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2010.

- ^ Lavington, Simon. "A brief history of British computers: the first 25 years (1948–1973)". British Computer Society. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Lee, Thomas H. (2003). The Design of CMOS Radio-Frequency Integrated Circuits (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-64377-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Puers, Robert; Baldi, Livio; Voorde, Marcel Van de; Nooten, Sebastiaan E. van (2017). Nanoelectronics: Materials, Devices, Applications, 2 Volumes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 14. ISBN 978-3-527-34053-8. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ a b Moskowitz, Sanford L. (2016). Advanced Materials Innovation: Managing Global Technology in the 21st century. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 165–167. ISBN 978-0-470-50892-3. Retrieved 28 August 2019.