Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed,[a] also called the Creed of Constantinople,[1] is the defining statement of belief of Nicene Christianity[2][3] and in those Christian denominations that adhere to it.

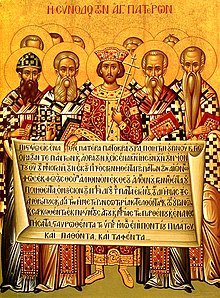

The original Nicene Creed was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. According to the traditional view, forwarded by the Council of Chalcedon of 451, the Creed was amended in 381 by the First Council of Constantinople as "consonant to the holy and great Synod of Nice."[4] However, many scholars comment on these ancient Councils saying "there is a failure of evidence" for this position since no one between the years of 381–451 thought of it in this light.[5] Further, a creed "almost identical in form" was used as early as 374 by St. Epiphanius of Salamis.[6] Nonetheless, the amended form is presently referred to as the Nicene Creed or the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed. J.N.D. Kelly, who stands among historians as an authority on creedal statements, disagrees with the aforementioned assessment. He argues that since Constantinople I was not considered ecumenical until Chalcedon in 451, the absence of documentation during this period does not logically necessitate rejecting it as an expansion of the original Nicene Creed of 325.[6]

The Nicene Creed is part of the profession of faith required of those undertaking important functions within the Orthodox, Catholic and Lutheran Churches.[7][8][9] Nicene Christianity regards Jesus as divine and "begotten of the Father".[10] Various conflicting theological views existed before the fourth century and these spurred the ecumenical councils which eventually developed the Nicene Creed, and various non-Nicene beliefs have emerged and re-emerged since the fourth century, all of which are considered heresies[11] by adherents of Nicene Christianity.

In Western Christianity, the Nicene Creed is in use alongside the less widespread Apostles' Creed[12][13][14] and Athanasian Creed.[15][8] However, part of it can be found as an "Authorized Affirmation of Faith" in the main volume of the Common Worship liturgy of the Church of England published in 2000.[16][17] In musical settings, particularly when sung in Latin, this creed is usually referred to by its first word, Credo. On Sundays and solemnities, one of these two creeds is recited in the Roman Rite Mass after the homily. In the Byzantine Rite, the Nicene Creed is sung or recited at the Divine Liturgy, immediately preceding the Anaphora (eucharistic prayer) is also recited daily at compline.[18][19]

History

[edit]

The purpose of a creed is to provide a doctrinal statement of correct belief among Christians amid controversy.[20] The creeds of Christianity have been drawn up at times of conflict about doctrine: acceptance or rejection of a creed served to distinguish believers and heretics, particularly the adherents of Arianism.[20] For that reason, a creed was called in Greek a σύμβολον, symbolon, which originally meant half of a broken object which, when fitted to the other half, verified the bearer's identity.[21] The Greek word passed through Latin symbolum into English "symbol", which only later took on the meaning of an outward sign of something.[22]

The Nicene Creed was adopted to resolve the Arian controversy, whose leader, Arius, a clergyman of Alexandria, "objected to Alexander's (the bishop of the time) apparent carelessness in blurring the distinction of nature between the Father and the Son by his emphasis on eternal generation".[23] Emperor Constantine called the Council at Nicaea to resolve the dispute in the church which resulted from the widespread adoption of Arius' teachings, which threatened to destabilize the entire empire. Following the formulation of the Nicene Creed, Arius' teachings were henceforth marked as heresy.[24]

The Nicene Creed of 325 explicitly affirms the Father as the "one God" and as the "Almighty," and Jesus Christ as "the Son of God", as "begotten of [...] the essence of the Father," and therefore as "consubstantial with the Father," meaning, "of the same substance"[25][26] as the Father; "very God of very God." The Creed of 325 does mention the Holy Spirit but not as "God" or as "consubstantial with the Father." The 381 revision of the creed at Constantinople (i.e., the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed), which is often simply referred to as the "Nicene Creed," speaks of the Holy Spirit as worshipped and glorified with the Father and the Son.[27]

The Athanasian Creed, formulated about a century later, which was not the product of any known church council and not used in Eastern Christianity, describes in much greater detail the relationship between Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The earlier Apostles' Creed, apparently formulated before the Arian controversy arose in the fourth century, does not describe the Son or the Holy Spirit as "God" or as "consubstantial with the Father."[27]

Thomas Aquinas stated that the phrase for us men, and for our salvation was to refute the error of Origen, "who alleged that by the power of Christ's Passion even the devils were to be set free." He also stated that the phrases stating Jesus was made incarnate by the Holy Spirit was to refute the Manicheans "so that we may believe that He assumed true flesh and not a phantastic body," and He came down from Heaven was to refute the error of Photinus, "who asserted that Christ was no more than a man." Furthermore, the phrase and He was made man was to "exclude the error of Nestorius, according to whose contention the Son of God ... would be said to dwell in man [rather] than to be man."[28]

Original Nicene Creed of 325

[edit]The original Nicene Creed was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea, which opened on 19 June 325. The text ends with anathemas against Arian propositions, preceded by the words: "We believe in the Holy Spirit" which terminates the statements of belief.[29][30][31][32][33]

F. J. A. Hort and Adolf von Harnack argued that the Nicene Creed was the local creed of Caesarea (an important center of Early Christianity)[34] recited in the council by Eusebius of Caesarea. Their case relied largely on a very specific interpretation of Eusebius' own account of the council's proceedings.[35] More recent scholarship has not been convinced by their arguments.[36] The large number of secondary divergences from the text of the creed quoted by Eusebius make it unlikely that it was used as a starting point by those who drafted the conciliar creed.[37] Their initial text was probably a local creed from a Syro-Palestinian source into which they inserted phrases to define the Nicene theology.[38] The Eusebian Creed may thus have been either a second or one of many nominations for the Nicene Creed.[39]

The 1911 Catholic Encyclopedia says that, soon after the Council of Nicaea, the church composed new formulae of faith, most of them variations of the Nicene Symbol, to meet new phases of Arianism, of which there were at least four before the Council of Sardica (341), at which a new form was presented and inserted in its acts, although the council did not accept it.[40]

Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed

[edit]What is known as the "Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed" or the "Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed",[b] received this name because it was adopted at the Second Ecumenical Council held in Constantinople in 381 as a modification of the original Nicene Creed of 325. In that light, it also came to be very commonly known simply as the "Nicene Creed". It is the only authoritative ecumenical statement of the Christian faith accepted by the Catholic Church (with the addition of the Filioque), the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Church of the East, and much of Protestantism including the Anglican communion.[41][42] (The Apostles' and Athanasian creeds are not as widely accepted.)[11]

It differs in a number of respects, both by addition and omission, from the creed adopted at the First Council of Nicaea. The most notable difference is the additional section:

And [we believe] in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver-of-Life, who proceedeth from the Father, who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified, who spake by the prophets. And [we believe] in one, holy, catholic and Apostolic Church. We acknowledge one Baptism for the remission of sins, [and] we look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen.[43]

Since the end of the 19th century,[44] scholars have questioned the traditional explanation of the origin of this creed, which has been passed down in the name of the council, whose official acts have been lost over time. A local council of Constantinople in 382 and the Third Ecumenical Council (Council of Ephesus of 431) made no mention of it,[45] with the latter affirming the 325 creed of Nicaea as a valid statement of the faith and using it to denounce Nestorianism. Though some scholarship claims that hints of the later creed's existence are discernible in some writings,[46] no extant document gives its text or makes explicit mention of it earlier than the Fourth Ecumenical Council at Chalcedon in 451.[44][45][47] Many of the bishops of the 451 council themselves had never heard of it and initially greeted it skeptically, but it was then produced from the episcopal archives of Constantinople, and the council accepted it "not as supplying any omission but as an authentic interpretation of the faith of Nicaea".[45] In spite of the questions raised, it is considered most likely that this creed was in fact introduced at the 381 Second Ecumenical Council.[11]

On the basis of evidence both internal and external to the text, it has been argued that this creed originated not as an editing of the original Creed proposed at Nicaea in 325, but as an independent creed (probably an older baptismal creed) modified to make it more like the Nicene Creed.[48] Some scholars have argued that the creed may have been presented at Chalcedon as "a precedent for drawing up new creeds and definitions to supplement the Creed of Nicaea, as a way of getting round the ban on new creeds in Canon 7 of Ephesus".[47] It is generally agreed that the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed is not simply an expansion of the Creed of Nicaea, and was probably based on another traditional creed independent of the one from Nicaea.[11][44]

The Third Ecumenical Council (Ephesus) reaffirmed the original 325 version[c] of the Nicene Creed and declared that "it is unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν) faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicaea" (i.e., the 325 creed). The word ἑτέραν is more accurately translated as used by the council to mean "different", "contradictory", rather than "another".[50] This statement has been interpreted as a prohibition against changing this creed or composing others, but not all accept this interpretation.[50] This question is connected with the controversy whether a creed proclaimed by an ecumenical council is definitive in excluding not only excisions from its text but also additions to it.[citation needed]

In one respect, the Eastern Orthodox Church's received text of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed differs from the earliest text,[51] which is included in the acts of the Council of Chalcedon of 451: The Eastern Orthodox Church uses the singular forms of verbs such as "I believe", in place of the plural form ("we believe") used by the council. Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches use exactly the same form of the creed, since the Catholic Church teaches that it is wrong to add "and the Son" to the Greek verb "ἐκπορευόμενον", though correct to add it to the Latin "qui procedit", which does not have precisely the same meaning.[52] The form generally used in Western churches does add "and the Son" and also the phrase "God from God", which is found in the original 325 Creed.[53]

Filioque controversy

[edit]In the late 6th century, some Latin-speaking churches added the word Filioque ("and the Son") to the description of the procession of the Holy Spirit, in what many Eastern Orthodox Christians have at a later stage argued is a violation of Canon VII[54] of the Third Ecumenical Council, since the words were not included in the text by either the Council of Nicaea or that of Constantinople.[55] This was incorporated into the liturgical practice of Rome in 1014.[52] Filioque eventually became one of the main causes for the East-West Schism in 1054, and the failures of the repeated union attempts.

Views on the importance of this creed

[edit]The view that the Nicene Creed can serve as a touchstone of true Christian faith is reflected in the name "symbol of faith", which was given to it in Greek and Latin, when in those languages the word "symbol" meant a "token for identification (by comparison with a counterpart)".[56]

In the Roman Rite mass, the Latin text of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, with "Deum de Deo" (God from God) and "Filioque" (and from the Son), phrases absent in the original text, was previously the only form used for the "profession of faith". The Roman Missal now refers to it jointly with the Apostles' Creed as "the Symbol or Profession of Faith or Creed", describing the second as "the baptismal Symbol of the Roman Church, known as the Apostles' Creed".[57]

Some evangelical and other Christians consider the Nicene Creed helpful and to a certain extent authoritative, but not infallibly so in view of their belief that only Scripture is truly authoritative.[58][59] Non-Trinitarian groups, such as the Church of the New Jerusalem, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Jehovah's Witnesses, explicitly reject some of the statements in the Nicene Creed.[60][61][62][63]

Ancient liturgical versions

[edit]There are several designations for the two forms of the Nicene Creed, some with overlapping meanings:

- Nicene Creed or the Creed of Nicaea is used to refer to the original version adopted at the First Council of Nicaea (325), to the revised version adopted by the First Council of Constantinople (381), to the liturgical text used by the Eastern Orthodox Church (with "I believe" instead of "We believe"),[64] to the Latin version that includes the phrase "Deum de Deo" and "Filioque",[65] and to the Armenian version, which does not include "and from the Son", but does include "God from God" and many other phrases.[66]

- Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed can stand for the revised version of Constantinople (381) or the later Latin version[67] or various other versions.[68]

- Icon/Symbol of the Faith is the usual designation for the revised version of Constantinople 381 in the Orthodox churches, where this is the only creed used in the liturgy.[citation needed]

- Profession of Faith of the 318 Fathers refers specifically to the version of Nicaea 325 (traditionally, 318 bishops took part at the First Council of Nicaea).[citation needed]

- Profession of Faith of the 150 Fathers refers specifically to the version of Constantinople 381 (traditionally, 150 bishops took part at the First Council of Constantinople).[citation needed]

This section is not meant to collect the texts of all liturgical versions of the Nicene Creed, and provides only three, the Greek, the Latin, and the Armenian, of special interest. Others are mentioned separately, but without the texts. All ancient liturgical versions, even the Greek, differ at least to some small extent from the text adopted by the First Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople. The Creed was originally written in Greek, owing among other things to the location of the two councils.[citation needed]

Although the councils' texts have "Πιστεύομεν [...] ὁμολογοῦμεν [...] προσδοκοῦμεν" ("we believe [...] confess [...] await"), the creed that the Churches of Byzantine tradition use in their liturgy has "Πιστεύω [...] ὁμολογῶ [...] προσδοκῶ" ("I believe [...] confess [...] await"), accentuating the personal nature of recitation of the creed. The Latin text, as well as using the singular, has two additions: "Deum de Deo" (God from God) and "Filioque" (and from the Son). The Armenian text has many more additions, and is included as showing how that ancient church has chosen to recite the creed with these numerous elaborations of its contents.[66]

An English translation of the Armenian text is added; English translations of the Greek and Latin liturgical texts are given at English versions of the Nicene Creed in current use.

Greek liturgical text

[edit]Πιστεύω εἰς ἕνα Θεόν, Πατέρα, Παντοκράτορα, ποιητὴν οὐρανοῦ καὶ γῆς, ὁρατῶν τε πάντων καὶ ἀοράτων.

Καὶ εἰς ἕνα Κύριον Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν, τὸν Υἱὸν τοῦ Θεοῦ τὸν μονογενῆ, τὸν ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς γεννηθέντα πρὸ πάντων τῶν αἰώνων·

φῶς ἐκ φωτός, Θεὸν ἀληθινὸν ἐκ Θεοῦ ἀληθινοῦ, γεννηθέντα οὐ ποιηθέντα, ὁμοούσιον τῷ Πατρί, δι' οὗ τὰ πάντα ἐγένετο.

Τὸν δι' ἡμᾶς τοὺς ἀνθρώπους καὶ διὰ τὴν ἡμετέραν σωτηρίαν κατελθόντα ἐκ τῶν οὐρανῶν καὶ σαρκωθέντα

ἐκ Πνεύματος Ἁγίου καὶ Μαρίας τῆς Παρθένου καὶ ἐνανθρωπήσαντα.

Σταυρωθέντα τε ὑπὲρ ἡμῶν ἐπὶ Ποντίου Πιλάτου, καὶ παθόντα καὶ ταφέντα.

Καὶ ἀναστάντα τῇ τρίτῃ ἡμέρᾳ κατὰ τὰς Γραφάς.

Καὶ ἀνελθόντα εἰς τοὺς οὐρανοὺς καὶ καθεζόμενον ἐκ δεξιῶν τοῦ Πατρός.

Καὶ πάλιν ἐρχόμενον μετὰ δόξης κρῖναι ζῶντας καὶ νεκρούς, οὗ τῆς βασιλείας οὐκ ἔσται τέλος.

Καὶ εἰς τὸ Πνεῦμα τὸ Ἅγιον, τὸ κύριον, τὸ ζῳοποιόν,

τὸ ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς ἐκπορευόμενον,

τὸ σὺν Πατρὶ καὶ Υἱῷ συμπροσκυνούμενον καὶ συνδοξαζόμενον,

τὸ λαλῆσαν διὰ τῶν προφητῶν.

Εἰς μίαν, Ἁγίαν, Καθολικὴν καὶ Ἀποστολικὴν Ἐκκλησίαν.

Ὁμολογῶ ἓν βάπτισμα εἰς ἄφεσιν ἁμαρτιῶν.

Προσδοκῶ ἀνάστασιν νεκρῶν.

Καὶ ζωὴν τοῦ μέλλοντος αἰῶνος.

Ἀμήν.[69][70]

Latin liturgical version

[edit]Credo in unum Deum,

Patrem omnipoténtem,

factórem cæli et terræ,

visibílium ómnium et invisibílium.

Et in unum Dóminum, Jesum Christum,

Fílium Dei unigénitum,

et ex Patre natum ante ómnia sǽcula.

Deum de Deo, lumen de lúmine, Deum verum de Deo vero,

génitum, non factum, consubstantiálem Patri:

per quem ómnia facta sunt.

Qui propter nos hómines et propter nostram salútem

descéndit de coelis.

Et incarnátus est de Spíritu Sancto

ex María vírgine, et homo factus est.

Crucifíxus étiam pro nobis sub Póntio Piláto;

passus et sepúltus est,

et resurréxit tértia die, secúndum Scriptúras,

et ascéndit in coelum, sedet ad déxteram Patris.

Et íterum ventúrus est cum glória,

judicáre vivos et mórtuos,

cujus regni non erit finis.

Et in Spíritum Sanctum, Dóminum et vivificántem:

qui ex Patre Filióque procédit.

Qui cum Patre et Fílio simul adorátur et conglorificátur:

qui locútus est per prophétas.

Et unam, sanctam, cathólicam et apostólicam Ecclésiam.

Confíteor unum baptísma in remissiónem peccatórum.

Et exspécto resurrectiónem mortuórum,

et vitam ventúri sǽculi. Amen.[71]

The Latin text adds "Deum de Deo" and "Filioque" to the Greek. On the latter see The Filioque Controversy above. Inevitably also, the overtones of the terms used, such as a παντοκράτορα, pantokratora and omnipotentem, differ (pantokratora meaning ruler of all; omnipotentem meaning omnipotent, almighty). The implications of the difference in overtones of "ἐκπορευόμενον" and "qui [...] procedit" was the object of the study The Greek and the Latin Traditions regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit published by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity in 1996.[72]

Again, the terms ὁμοούσιον and consubstantialem, translated as "of one being" or "consubstantial", have different overtones, being based respectively on Greek οὐσία (stable being, immutable reality, substance, essence, true nature),[73] and Latin substantia (that of which a thing consists, the being, essence, contents, material, substance).[74]

"Credo", which in classical Latin is used with the accusative case of the thing held to be true (and with the dative of the person to whom credence is given),[75] is here used three times with the preposition "in", a literal translation of the Greek εἰς (in unum Deum [...], in unum Dominum [...], in Spiritum Sanctum [...]), and once in the classical preposition-less construction (unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam).[citation needed]

Armenian liturgical text

[edit]

Հաւատամք ի մի Աստուած, ի Հայրն ամենակալ, յարարիչն երկնի եւ երկրի, երեւելեաց եւ աներեւութից։

Եւ ի մի Տէր Յիսուս Քրիստոս, յՈրդին Աստուծոյ, ծնեալն յԱստուծոյ Հօրէ, միածին՝ այսինքն յէութենէ Հօր։

Աստուած յԱստուծոյ, լոյս ի լուսոյ, Աստուած ճշմարիտ յԱստուծոյ ճշմարտէ, ծնունդ եւ ոչ արարած։ Նոյն ինքն ի բնութենէ Հօր, որով ամենայն ինչ եղեւ յերկինս եւ ի վերայ երկրի, երեւելիք եւ աներեւոյթք։

Որ յաղագս մեր մարդկան եւ վասն մերոյ փրկութեան իջեալ ի յերկնից՝ մարմնացաւ, մարդացաւ, ծնաւ կատարելապէս ի Մարիամայ սրբոյ կուսէն Հոգւովն Սրբով։

Որով էառ զմարմին, զհոգի եւ զմիտ, եւ զամենայն որ ինչ է ի մարդ, ճշմարտապէս եւ ոչ կարծեօք։

Չարչարեալ, խաչեալ, թաղեալ, յերրորդ աւուր յարուցեալ, ելեալ ի յերկինս նովին մարմնովն, նստաւ ընդ աջմէ Հօր։

Գալոց է նովին մարմնովն եւ փառօք Հօր ի դատել զկենդանիս եւ զմեռեալս, որոյ թագաւորութեանն ոչ գոյ վախճան։

Հաւատամք եւ ի սուրբ Հոգին, յանեղն եւ ի կատարեալն․ Որ խօսեցաւ յօրէնս եւ ի մարգարէս եւ յաւետարանս․ Որ էջն ի Յորդանան, քարոզեաց զառաքեալսն, եւ բնակեցաւ ի սուրբսն։

Հաւատամք եւ ի մի միայն, ընդհանրական եւ առաքելական, Սուրբ Եկեղեցի․ ի մի մկրտութիւն, յապաշխարհութիւն, ի քաւութիւն եւ ի թողութիւն մեղաց․ ի յարութիւնն մեռելոց․ ի դատաստանն յաւիտենից հոգւոց եւ մարմնոց․ յարքայութիւնն երկնից, եւ ի կեանսն յաւիտենականս։

English translation of the Armenian version

[edit]We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, the maker of heaven and earth, of things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the begotten of God the Father, the Only-begotten, that is of the substance of the Father.

God of God, Light of Light, true God of true God, begotten and not made; of the very same nature of the Father, by Whom all things came into being, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible.

Who for us humanity and for our salvation came down from heaven, was incarnate, became human, was born perfectly of the holy virgin Mary by the Holy Spirit.

By whom He took body, soul, and mind, and everything that is in man, truly and not in semblance.

He suffered, was crucified, was buried, rose again on the third day, ascended into heaven with the same body, [and] sat at the right hand of the Father.

He is to come with the same body and with the glory of the Father, to judge the living and the dead; of His kingdom there is no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the uncreate and the perfect; Who spoke through the Law, the prophets, and the Gospels; Who came down upon the Jordan, preached through the apostles, and lived in the saints.

We believe also in only One, Universal, Apostolic, and [Holy] Church; in one baptism with repentance for the remission and forgiveness of sins; and in the resurrection of the dead, in the everlasting judgement of souls and bodies, in the Kingdom of Heaven and in the everlasting life.[76]

Other ancient liturgical versions

[edit]The version in the Church Slavonic language, used by several Eastern Orthodox churches is practically identical with the Greek liturgical version.[citation needed]

This version is used also by some Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches. Although the Union of Brest excluded addition of the Filioque, this was sometimes added by Ruthenian Catholics,[77] whose older liturgical books also show the phrase in brackets, and by Ukrainian Catholics. Writing in 1971, the Ruthenian scholar Casimir Kucharek noted, "In Eastern Catholic Churches, the Filioque may be omitted except when scandal would ensue. Most of the Eastern Catholic Rites use it."[78] However, in the decades that followed 1971 it has come to be used more rarely.[79][80][81]

The versions used by Oriental Orthodoxy and the Church of the East[82] may differ from the Greek liturgical version in having "We believe", as in the original text, instead of "I believe".[83]

Indulgence

[edit]In the Roman Catholic Church, to obtain the plenary indulgence once a day, it is necessary to visit a church or oratory to which the indulgence is attached and the recitation of the Sunday prayers, Creed and Hail Mary.[84]

Recitation of the Apostles' Creed or the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed is required to obtain a partial indulgence.[85]

English translations

[edit]The version found in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer is still commonly used by some English speakers, but more modern translations are now more common. The International Consultation on English Texts published an English translation of the Nicene Creed, first in 1970 and then in successive revisions in 1971 and 1975. These texts were adopted by several churches.

The Roman Catholic Church in the United States adopted the 1971 version in 1973. The Catholic Church in other English-speaking countries adopted the 1975 version in 1975. They continued to use them until 2011, when it replaced them with the version in the Roman Missal third edition. The 1975 version was included in the 1979 Episcopal Church (United States) Book of Common Prayer, but with one variation: in the line "For us men and for our salvation", it omitted the word "men".

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ /ˈnaɪsiːn/; Koinē Greek: Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας, romanized: Sýmvolon tis Nikéas

- ^ Both names are common. Instances of the former are in the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church and in the Roman Missal, while the latter is used consistently by the Faith and Order Commission. "Constantinopolitan Creed" can also be found, but very rarely.

- ^ It was the original 325 creed, not the one that is attributed to the Second Ecumenical Council in 381, that was recited at the Council of Ephesus.[49]

References

[edit]- ^ Cone, Steven D.; Rea, Robert F. (2019). A Global Church History: The Great Tradition through Cultures, Continents and Centuries. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. lxxx. ISBN 978-0-567-67305-3.

- ^ World Encyclopaedia of Interfaith Studies: World religions. Jnanada Prakashan. 2009. ISBN 978-81-7139-280-3.

In the most common sense, "mainstream" refers to Nicene Christianity, or rather the traditions which continue to claim adherence to the Nicene Creed.

- ^ Seitz, Christopher R. (2001). Nicene Christianity: The Future for a New Ecumenism. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1-84227-154-4. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ^ "Council of Chalcedon". New Advent. Session II.

- ^ Bright, William (1882). Notes on the Canons of the First Four General Councils. Oxford : Clarendon Press. pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b Davis, Leo Donald (1988). The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology. Theology and Life Series 21. Wilmington, DE: Michael Glazier. pp. 121–124. ISBN 0-8146-5616-1.

- ^ "Profession of Faith". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b "The Three Ecumenical or Universal Creeds" (PDF). Concordia University Ann Arbor. p. 1. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ "Code of Canon Law - IntraText". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Meister, Chad; Copan, Paul (2010). Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-18000-4.

- ^ a b c d "Nicene Creed". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ^

Jenner, Henry (1908). "Liturgical Use of Creeds". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Jenner, Henry (1908). "Liturgical Use of Creeds". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "The Nicene Creed - Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese". Antiochian.org. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ "The Orthodox Faith – Volume I – Doctrine and Scripture – The Symbol of Faith – Nicene Creed". oca.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Weinandy, Thomas G.; Keating, Daniel A. (1 November 2017). Athanasius and His Legacy: Trinitarian-Incarnational Soteriology and Its Reception. Fortress Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-5064-0629-9.

In the Lutheran Book of Concord (1580), the Quicunque is given equal honor with the Apostles' and Nicene Creeds; the Belgic Confession of the Reformed church (1566) accords it authoritative status; and the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles declare it as one of the creeds that ought to be received and believed.

- ^ Morin 1911

- ^ Kantorowicz 1957, p. 17

- ^ [1] Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Archbishop Averky Liturgics – The Small Compline", Retrieved 14 April 2013

- ^ [2] Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Archbishop Averky Liturgics – The Symbol of Faith", Retrieved 14 April 2013

- ^ a b Lamberts, Jozef (2020). With One Spirit: The Roman Missal and Active Participation (in Arabic). Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8146-6556-5.

- ^ Liddell and Scott: σύμβολον Archived 11 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine; cf. split tally

- ^ Symbol: early 15c., "creed, summary, religious belief," from Late Latin symbolum "creed, token, mark," from Greek symbol "token, watchword, sign by which one infers; ticket, a permit, licence" (the word was applied c. 250 by Cyprian of Carthage to the Apostles' Creed, on the notion of the "mark" that distinguishes Christians from pagans), literally "that which is thrown or cast together," from assimilated form of syn- "together" (see syn-) + bole "a throwing, a casting, the stroke of a missile, bolt, beam," from bol-, nominative stem of ballein "to throw" (from PIE root *gwele- "to throw, reach"). The sense evolution in Greek is from "throwing things together" to "contrasting" to "comparing" to "token used in comparisons to determine if something is genuine." Hence, the "outward sign" of something. The meaning "something which stands for something else" was first recorded in 1590 (in "Faerie Queene"). As a written character, 1610s. (Harper, Douglas (2023). "Symbol". Etymology Online. Archived from the original on 26 February 2023. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Heresiology: The Invention of Heresy and Schism

at the Internet Archive

at the Internet Archive

- ^ Wickham, Chris (2009). The Inheritance of Rome: A History of Europe from 400 to 1000 (1st ed.). New York: Viking. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-670-02098-0.

- ^ "Definition of HOMOOUSIAN". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "homousian", The Free Dictionary, archived from the original on 6 September 2021, retrieved 7 September 2021

- ^ a b Denzinger, Henry (1957). The Sources of Catholic Dogma (30th ed.). B. Herder Book Co. p. 3.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas (1993). Light of Faith: The Compendium of Theology. Sophia Institute Press. pp. 273–274.

- ^ Hefele, Karl Joseph von (1894). A History of the Christian Councils: From the Original Documents, to the Close of the Council of Nicaea, A.D. 325. T. & T. Clark. p. 275. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ Leith, John H. (1982). Creeds of the Churches: A Reader in Christian Doctrine, from the Bible to the Present. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 28–31. ISBN 978-0-8042-0526-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gwynn, David M. (2014). Christianity in the Later Roman Empire: A Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-4411-3735-7. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 7 June 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "First Council of Nicaea – 325 AD". 20 May 0325. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Bindley, T. Herbert. The Oecumenical Documents of the Faith Methuen & Co 4th edn. 1950 revised by Green, F.W. pp. 15, 26–27

- ^ "Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical notes. Volume II. The History of Creeds". Ccel.org. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Kelly J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds Longmans (1963) pp. 217–218

- ^ Williams, Rowan. Arius SCM (2nd Edn 2001) pp. 69–70

- ^ Kelly, J.N.D. (1963). Early Christian Creeds. Longmans. pp. 218ff.

- ^ Kelly J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds Longmans (1963) pp. 22–30

- ^ Denzinger, Henry (1957). The Sources of Catholic Dogma (30th ed.). B. Herder Book Co. p. 9.

- ^

Wilhelm, Joseph (1911). "The Nicene Creed". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Wilhelm, Joseph (1911). "The Nicene Creed". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Religion Facts, four of the five Protestant denominations studied agree with the Nicene Creed and the fifth may as well, they just don't do creeds in general". Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ "Christianity Today reports on a study that shows most evangelicals believe the basic Nicene formulation". 28 October 2014. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ^ Schaff's Seven Ecumenical Councils: Second Ecumenical: The Holy Creed Which the 150 Holy Fathers Set Forth... Archived 5 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds Longmans (19602) pp. 305, 307, 322–331 respectively

- ^ a b c Davis, Leo Donald S.J., The First Seven Ecumenical Councils, The Liturgical Press, Collegeville, Minnesota, 1990, ISBN 0-8146-5616-1, pp. 120–122, 185

- ^ Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Creeds London, 1973

- ^ a b Richard Price, Michael Gaddis (editors), The Acts of the Council of Chalcedon (Liverpool University Press 2005 Archived 8 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-0-85323-039-7), p. 3

- ^ "Philip Schaff, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. III: article Constantinopolitan Creed". Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ^ "The Third Ecumenical Council. The Council of Ephesus, p. 202". Archived from the original on 16 August 2000. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ a b "NPNF2-14. The Seven Ecumenical Councils". Ccel.org. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ^ "Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical notes. Volume II. The History of Creeds". Ccel.org. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 8 December 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ^ a b "Greek and Latin Traditions on Holy Spirit". Ewtn.com. Archived from the original on 28 December 2018.

- ^ "Creeds of Christendom, with a History and Critical notes. Volume II. The History of Creeds". Ccel.org. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ^ "Canon VII". Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ^ For a different view, see e.g. Excursus on the Words πίστιν ἑτέραν Archived 21 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ See etymology given in "Symbol". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Fifth ed.). 2019. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Ordo Missae, 18–19" (PDF). Usccb.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Kehn, N. R. (2009). "Sola Scriptura". Restoring the Restoration Movement: A look under the Hood at the Doctrines that Divide. LaVergne, TN: Xulon Press. ISBN 978-1-60791-358-0. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Credo Meditations on Thenicene Creed. Chalice Press. pp. xiv–xv. ISBN 978-0-8272-0592-5. Archived from the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ Timothy Larsen, Daniel J. Treier, The Cambridge Companion to Evangelical Theology Archived 8 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine (Cambridge University Press 2007 ISBN 978-0-521-84698-1, p. 4

- ^ Oaks, Dallin H. (May 1995). Apostasy And Restoration Archived 22 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Ensign. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- ^ Stephen Hunt, Alternative Religions (Ashgate 2003 Archived 8 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-0-7546-3410-2), p. 48

- ^ Charles Simpson, Inside the Churches of Christ (Arthurhouse 2009 Archived 8 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 978-1-4389-0140-4), p. 133

- ^ "Orthodox Prayer: The Nicene Creed". Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ This version is called the Nicene Creed in Catholic Prayers Archived 27 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Creeds of the Catholic Church Archived 4 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Brisbane Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, etc.

- ^ a b What the Armenian Church calls the Nicene Creed is given in the Armenian Church Library Archived 24 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, St Leon Armenian Church Archived 16 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Armenian Diaconate Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, etc.]

- ^ E.g.,"Roman Missal | Apostles' Creed". Wentworthville: Our Lady of Mount Carmel. 2011. Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 30 September 2016.

Instead of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, especially during Lent and Easter Time, the baptismal Symbol of the Roman Church, known as the Apostles' Creed, may be used

- ^ Philip Schaff, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. III: article Constantinopolitan Creed Archived 24 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine lists eight creed-forms calling themselves Niceno-Constantinopolitan or Nicene.

- ^ Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America: Liturgical Texts. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Archived 9 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Η ΘΕΙΑ ΛΕΙΤΟΥΡΓΙΑ Archived 4 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Church of Greece.

- ^ Missale Romanum. Vatican City: Administratio Patrimonii Sedis Apostolicae. 2002.

- ^ Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity (20 September 1995). "The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit". L'Osservatore Romano English Edition., p. 9

- ^ "οὐσί-α". Archived from the original on 18 August 2007. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, A Latin Dictionary: substantia Archived 2 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charlton T. Lewis, A Latin Dictionary: credo Archived 24 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Text in Armenian, with transliteration and English translation" (PDF). Armenianlibrary.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^

Shipman, Andrew (1912). "Ruthenian Rite". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Shipman, Andrew (1912). "Ruthenian Rite". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Kucharek, Casimir (1971). The Byzantine-Slav Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom: Its Origin and Evolution. Combermere, Ontario, Canada: Alleluia Press. p. 547. ISBN 0-911726-06-3.

- ^ Babie, Paul. "The Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church in Australia and the Filioque: A Return to Eastern Christian Tradition". Compass. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ "Pastoral Letter of the Ukrainian Catholic Hierarchy in Canada, 1 September 2005". Archeparchy.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ "Mark M. Morozowich, "Pope John Paul II and Ukrainian Catholic Liturgical Life: Renewal of Eastern Identity"". Stsophia.us. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ Creed of Nicaea Archived 20 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Assyrian Church of the East)

- ^ *Nicene Creed Archived 24 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Armenian Apostolic Church)

- The Coptic Orthodox Church: Our Creed Archived 19 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Coptic Orthodox Church)

- Nicene Creed Archived 26 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church)

- The Nicene Creed Archived 23 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church)

- The Nicene Creed Archived 7 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine (Syriac Orthodox Church)

- ^ Enchiridion Indulgentiarum, Concessiones, No. 19A, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 4th ed., 2004. ISBN 88-209-2785-3.

- ^ Enchiridion Indulgentiarum, Concessiones, No. 28 §3, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 4th ed., 2004. ISBN 88-209-2785-3.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ayres, Lewis (2006). Nicaea and Its Legacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-875505-8.

- A. E. Burn, The Council of Nicaea (1925)

- G. Forell, Understanding the Nicene Creed (1965)

- Kelly, John N. D. (2006) [1972]. Early Christian Creeds (3rd ed.). London-New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-9216-6.

- Ritter, Adolf Martin (1965). Das Konzil von Konstantinopel und sein Symbol: Studien zur Geschichte und Theologie des II. Ökumenischen Konzils [The Council of Constantinople and its Symbol: Studies in the History and Theology of the Second Ecumenical Council] (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-666-55118-5.

- Kinzig, Wolfram (2021). Das Glaubensbekenntnis von Konstantinopel (381): Herkunft, Geltung und Rezeption. Neue Texte und Studien zu den antiken und frühmittelalterlichen Glaubensbekenntnissen II [The Creed of Constantinople (381): Origin, Validity and Reception. New Texts and Studies on the Ancient and Early Medieval Creeds II]. Arbeiten zur Kirchengeschichte 147 (in German). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-071461-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Extensive discussion of the texts of the First Council of Nicea Archived 27 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Philip Schaff, Creeds of Christendom Volume I: Nicene Creed

- "Essays on the Nicene Creed from the Wisconsin Lutheran Seminary Library". Archived from the original on 9 May 2015.

- "The Nicene Creed", run time 42 minutes, BBC In Our Time audio history series, moderator and historians, Episode 12-27-2007 Archived 1 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit] The full text of Nicene Creed at Wikisource

The full text of Nicene Creed at Wikisource Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Symbolum Nicænum Costantinopolitanum

Latin Wikisource has original text related to this article: Symbolum Nicænum Costantinopolitanum Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Nicene Creed in Greek

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Nicene Creed in Greek- Athanasius, De Decretis or Defence of the Nicene Definition Archived 13 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Line-by-Line Roman Catholic Explanation of the Nicene Creed". Archived from the original on 18 February 2006.

- "Nicene Creed in languages of the world".

- "Modern English translations of the documents produced at Nicaea". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)  This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Nicene and Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Nicene and Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.