New York City Criminal Court

| |

| Court overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 1, 1962 |

| Jurisdiction | New York City |

| Court executive |

|

| Parent department | New York State Unified Court System |

| Key documents |

|

| Website | nycourts.gov/…/criminal |

The Criminal Court of the City of New York is a court of the State Unified Court System in New York City that handles misdemeanors (generally, crimes punishable by fine or imprisonment of up to one year) and lesser offenses, and also conducts arraignments (initial court appearances following arrest) and preliminary hearings in felony cases (generally, more serious offenses punishable by imprisonment of more than one year).[1][2]

It is a single citywide court.[3] The Deputy Chief Administrative Judge for the New York City Courts is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations of the NYC trial-level courts, and works with the Administrative Judge of the Criminal Court in order to allocate and assign judicial and nonjudicial personnel resources.[4] One hundred seven judges may be appointed by the Mayor to ten-year terms, but most of those appointed have been transferred to other courts by the Office of Court Administration.

Criminal procedure

[edit]Most people who are arrested and prosecuted in New York City will appear before a Criminal Court judge for arraignment. The New York Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) is the primary criminal procedure law.

Felonies are heard by the Supreme Court. Some violations and other issues are adjudicated by other city and state administrative courts, e.g., Krimstock hearings are conducted by the city Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, parking violations are adjudicated by the city DOF Parking Violations Bureau, and non-parking traffic violations are adjudicated by the state DMV Traffic Violations Bureau.

Arrest to arraignment

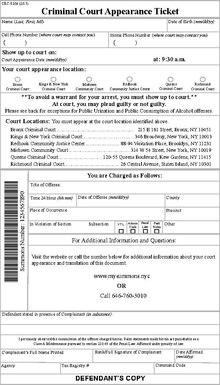

[edit]New York police officers may arrest someone they have reason to believe has committed a felony, misdemeanor, or violation,[5] or pursuant to an arrest warrant. Those arrested are booked at "central booking" and interviewed by a representative of the Criminal Justice Agency for the purposes of recommending bail or remand at arraignment.[5] In New York state, the time from arrest to arraignment must be within 24 hours.[6][7] Police may also release a person with an appearance ticket directing a defendant to appear for arraignment in the future: with a desk appearance ticket (DAT) after arrest, or a universal summons without arrest.[8][9]

At arraignment, the accused is informed of the charges against them and submits a plea (and may accept a plea bargain).[5] The accused have a right to a lawyer.[5] Arraignments are held every day from 9:00 am to 1:00 am.[5][14] At arraignment the prosecutor may also provides defense counsel with certain "notices", such as notices about police lineups and statements made by the defendant to police.[15]

After notices are served, the prosecutor may ask, for certain offenses, the court to keep the accused in jail (remanded) or released on bail.[5][16][17] Otherwise, the accused is released on their own recognizance (ROR'd) with the least restrictive conditions necessary to reasonably assure the person will come back to court.[17] If the accused is released, the accused must appear in court every time their case is calendared (scheduled for a court hearing), and if they fail to appear the judge may forfeit their bail and issue a bench warrant for their arrest, although judges may excuse defendants from having to show up at every court appearance.[5][18]

The decision to set bail and the amount of bail to set are discretionary, and the central issue regarding bail is insuring the defendant's future appearances in court; factors to be taken into consideration are defined in Criminal Procedure Law § 510.30.[19] In practice, bail amounts are typically linked to charge severity rather than risk of failure to appear in court, judges overwhelmingly rely only on cash bail and commercial bail bonds instead of other forms of bail, and courts rarely inquire into the defendant's financial resources to understand what amount of bail might be securable by them.[20][21]

Felony indictment

[edit]For those accused of a felony, their case is sent to a court part where felony cases await the action of the grand jury.[5] If the grand jury finds that there is enough evidence that the accused has committed a crime, it may file an indictment.[5] If the accused waives their right to a grand jury, the prosecutor will file a Superior Court Information (SCI).[5] If the grand jury votes an indictment, the case will be transferred from Criminal Court to the Supreme Court for another arraignment.[5] This arraignment is similar to the arraignment in Criminal Court, and if the accused does not submit a guilty plea, the case will be adjourned to a calendar part.[5]

Felony defendants must be released on CPL § 180.80 day if they haven't been indicted, which is to say that unless a grand jury has indicted the defendant and a hearing has commenced within 120 hours/5 days (with an additional 24 hours allowed for weekends and holidays, i.e., 144 hours/6 days), or proof that the indictment was voted within 120 hours, and unless the delay was due to a request of the defendant, and absent a compelling reason for the prosecution's delay, the defendant must be released on their own recognizance (ROR'd).[5][22][23]

Pre-trial

[edit]

A bail review in Supreme Court may be requested by misdemeanor defendants who cannot make bail at the CPL § 170.70 day appearance (the five- to six-day deadline for conversion of a complaint to an information), normally to be scheduled three business days after the appearance.[24][25][26] The government must be ready for trial within 6 months for a felony, 90 days for a class A misdemeanor, 60 days for a class B misdemeanor, and within 30 days for a violation, subject to excluded periods (ready rule).[27][28] A defendant must be released on bail or ROR'd if they are in jail after a specified time of pretrial detention (bail review): within 90 days for a felony, within 30 days for an at-least-3-months misdemeanor, within 15 days for a maximum-3-months misdemeanor, and within 5 days for a violation, subject to excluded periods.[27][28]

Plea bargain negotiations take place in the AP Parts prior to the case being in a trial-ready posture, and depending upon caseloads, the judges in the AP Parts may conduct pre-trial and felony motion hearings.[29] The most common pre-trial evidence suppression hearings are Mapp (warrantless searches and probable cause), Dunaway (confessions), Huntley (Miranda rights), Wade (identification evidence like lineups), and Johnson (Terry stops) hearings.[30] Trial Parts also conduct pre-trial motion hearings, including Sandoval (witness impeachment) and Molineux (admissibility of prior uncharged crimes) hearings.[31] Once pretrial hearings are completed, the case is considered ready for trial and will usually be transferred to a courtroom that specializes in handling trials.

Trial

[edit]In New York State, only those individuals charged with a serious crime, defined as one where the defendant faces more than six months in jail, are entitled to a jury trial; those defendants facing six months' incarceration or less are entitled to a bench trial before a judge.[31] Defendants in summons court may waive their right to a trial before a judge and have the trial held by a judicial hearing officer.[32][33][34]

Appeal

[edit]Appeals are to the Appellate Terms of the New York Supreme Court, established separately in the First Department (Manhattan and the Bronx) and Second Department (Brooklyn, Queens, and Staten Island) of the Appellate Division.[35]

Structure

[edit]There are several specialized parts of the Criminal Court which handle specific subject areas.

Summons court

[edit]

The Summons All Purpose Part (SAP) hears cases brought to court by universal summonses issued by law enforcement personnel.[36] Summons court handles low-level offenses.[37][38][39][40][41] Defendants may waive their right to a trial before a judge and have the trial held by a judicial hearing officer.[32][33][34]

The District Attorney does not staff the SAP Part.[42][36] The NYPD's Legal Bureau has a memorandum of understanding with the Manhattan District Attorney allowing the NYPD to selectively prosecute summons court cases.[43] The summons court is sometimes called the "People's Court" because Criminal Court judges routinely authorize summonses and informations based upon the sworn allegations of private citizens who seek redress for criminal acts against them, and the entire proceeding is generally one of private or court-conducted trial.[36]

Problem-solving courts

[edit]The state court system has a number of problem-solving courts.[44] The Midtown Community Court is a community court which arraigns defendants who are arrested in the Times Square, Hell's Kitchen, and Chelsea neighborhoods and charged with any non-felony offense.[45][46] The Red Hook Community Justice Center is a multi-jurisdictional community court in Red Hook, Brooklyn, for example hearing family, civil and criminal "quality of life" cases, as well as youth court, and uses mediation, restitution, community service orders and drug treatment.[46][47]

Criminal Court operates domestic violence or "DV" courts within every county.[48] Domestic violence courts are forums that focus on crimes related to domestic violence and abuse and improving the administration of justice surrounding these types of crimes.[48] The Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens operates DV Complexes, which include an All-Purpose Part and Trial Parts dedicated to adjudicating these types of crimes, while in Richmond all DV cases are heard in the regular AP Part.[48]

Other

[edit]Defendants arraigned on felony or misdemeanor complaints are initially arraigned in the arraignment part of the Criminal Court.[49] The all-purpose or "AP" parts are the motion parts of the Criminal Court.[29] Plea bargain negotiations take place in these courtrooms prior to the case being in a trial-ready posture, and depending upon caseloads the judges in the AP Parts may conduct pre-trial hearings, felony hearings, and bench trials.[29]

Criminal Court has preliminary jurisdiction over felony cases filed in New York City, and retains jurisdiction of the felony cases until a grand jury hears the case and indicts the defendant.[50] Defendants charged with felonies are arraigned in the Criminal Court arraignment parts and cases are then usually sent to a felony waiver part to await grand jury action.[50] Felony waiver parts are staffed by Criminal Court judges designated as Acting Supreme Court Justices.[50] Felony waiver parts also hear motions, bail applications, and extradition matters.[50]

Trial Parts in the Criminal Court handle most of the trials, although some trials are conducted in the AP parts.[31]

Administration

[edit]The court is supervised by an Administrator, or Administrative Judge if a judge.[51] The Deputy Chief Administrator for the New York City Courts, or Deputy Chief Administrative Judge if a judge, is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day operations of the trial-level courts located in New York City, and works with the Administrator of the Criminal Court in order to allocate and assign judicial and nonjudicial personnel resources to meet the needs and goals of those courts.[4] The Criminal Court Administrator is assisted by Supervising Judges who are responsible in the on-site management of the trial courts, including court caseloads, personnel, and budget administration, and each manage a particular type of court within a county or judicial district.[51] The chief clerk assists the administrators in carrying out their responsibilities for supervising the day-to-day operations of the trial courts.[52] The Criminal Court Act made the City responsible for costs for personnel etc.[53] The court is not included in the New York State Courts Electronic Filing System (NYSCEF).

| Part of a series on |

| New York State Unified Court System |

|---|

|

|

|

Specialized |

In the State Legislature, the Senate Judiciary and Assembly Judiciary standing committees conduct legislative oversight, budget advocacy, and otherwise report bills on the judicial branch, both state and local courts.[54][55] The City Bar Criminal Courts Committee studies the workings of the criminal courts, while the Criminal Justice Operations Committee analyzes the criminal justice system more broadly.

Personnel

[edit]Judges

[edit]New York City Criminal Court judges are appointed by the Mayor of New York City to 10-year terms from a list of candidates submitted by the Mayor's Advisory Committee on the Judiciary.[1][56][57]

The Mayor's Advisory Committee is composed of up to nineteen members, all of whom are volunteers and are appointed with the Mayor's approval: the Mayor selects nine members; the Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals nominates four members; the Presiding Justices of the Appellate Divisions of the Supreme Court for the First and Second Judicial Departments each nominate two members; and deans of the law schools within New York City, on an annual rotating basis, each nominate one member.[56] In addition, the Committee on the Judiciary of the New York City Bar Association, in conjunction with the county bar association in the relevant county, investigates and evaluates the qualifications of all candidates for judicial office in New York City.[56]

Once a judge is appointed by the Mayor to the Criminal Court, they can be transferred from one court to another by the Office of Court Administration, and after two years' service in the lower courts, they may be designated by the Chief Administrator of the Courts as an Acting Supreme Court Justice with the same jurisdiction as a Supreme Court Justice upon consultation and agreement with the presiding justice of the appropriate Appellate Division.[58] The mayor may appoint 107 Criminal Court judges, but only about 73 to 74 currently work in Criminal Court: 46 of these are mayorally appointed Criminal Court judges, and the remaining 27 are Civil Court judges (some elected and some mayorally appointed) assigned to Criminal Court; the other approximately 60 mayorally appointed Criminal Court judges have been designated Acting Supreme Court judges to sit in Supreme Court hearing felony cases.[59][60]

Judicial hearing officers

[edit]Judicial hearing officers (JHOs) adjudicate most summons court (SAP Part) cases, assist in compliance parts in domestic violence cases, and in the New York Supreme Court monitor substance abuse program defendants, conduct pre-trial suppression hearings and make recommended findings of fact and law to sitting judges.[32][61][62][63] JHOs are appointed by the Chief Administrator.[64][65]

Attorneys

[edit]By law, the city must provide criminal representation by any combination of a public defender, legal aid society, and/or panel of qualified lawyers (pursuant to County Law Article 18-B).[66] The Legal Aid Society is contracted as the city's primary provider of criminal legal aid, along with New York County Defender Services in Manhattan, Brooklyn Defender Services in Brooklyn, The Bronx Defenders in the Bronx, Queens Defenders in Queens, and the Neighborhood Defender Service in northern Manhattan.[67] For a comparison of relative activity in 2009, legal aid societies handled 290,251 cases of which 568 went to trial, whereas 18-B lawyers represented 42,212 defendants of which 623 went to trial.[68]

The District Attorney does not staff the summons court (SAP Part), and the summons court proceedings are generally one of a private or court-conducted trial.[36] District attorneys are legally permitted to delegate the prosecution of petty crimes or offenses, and the NYPD's Legal Bureau has a memorandum of understanding with the district attorneys, at least in Manhattan, allowing the NYPD to selectively prosecute summons court cases.[69][70][71][43]

Analysis and criticism

[edit]The Court of Appeals ruled in 1991 that most people arrested must be released if they are not arraigned within 24 hours.[6][7] In 2013, for the first time since 2001, the average time it took to arraign defendants fell below 24 hours in all five boroughs.[72]

But there have been accusations of systematic trial delays,[73][74] especially with regards to the New York City stop-and-frisk program.[75] Out of more than 11,000 misdemeanor cases pending in 2012 in the Bronx, there were 300 misdemeanor trials.[75] The Bronx criminal courts were responsible for more than half of the cases in New York City's criminal courts that were over two years old, and for two-thirds of the defendants waiting for their trials in jail for more than five years.[76] In 2016, councilman Rory Lancman, noting that only about half of the about 107 appointed Criminal Court judges currently serve because the Chief Administrative Judge and Office of Court Administration have transferred them to Supreme Court to hear felony cases, said major reasons for the backlogs were a shortage of judges, court officers and courtrooms; a haphazard discovery process that frustrates timely plea deal negotiations; and a speedy trial statute unique to New York that allows the parties to game the system.[77][60] The New York Times editorial board has criticized the Criminal Court judges for rarely excusing defendants from having to show up at every court appearance, as allowed by law, instead requiring them "to return to court every several weeks and spend all day waiting for their cases to be called, only to be told that the proceedings are being put off for another month ... [meaning] these defendants miss work, lose wages and in some cases their jobs."[18]

New York City's use of remand (pre-trial detention) has also been criticized.[78] Almost without exception, New York judges only set two kinds of bail at arraignment, straight cash or commercial bail bond, while other options exist such as partially secured bonds, which only require a tenth of the full amount as a down payment to the court (and presumably refunded when redeemed), and unsecured bonds, which don't require any up front payment.[79][80][81] The New York City Criminal Justice Agency has stated that only 44 percent of defendants offered bail are released before their case concludes.[78] A report by Human Rights Watch found that among defendants arrested in New York City in 2008 on nonfelony charges who had bail set at $1,000 or less, 87 percent were jailed because they were unable to post the bail amount at their arraignment, and that 39 percent of the city's jail population consisted of pre-trial detainees who were in jail because they had not posted bail.[78][82][83] A report by the Vera Institute of Justice concluded that, in Manhattan, black and Latino defendants were more likely to be held in jail before trial and more likely to be offered plea bargains that include a prison sentence than whites and Asians charged with the same crimes.[84]

It is said that excessive pre-trial detention and the accompanying systematic trial delays are used to pressure defendants to accept plea bargains.[80][85][86][87][88]

In June 2014 it was reported that Brooklyn's change to a more wealthy, more Caucasian population has had a negative effect for defendants in the criminal cases of Brooklyn, which is largely composed of minorities, and reductions in awards in civil cases. It was called the Williamsburg effect because of that neighborhood's gentrification. Brooklyn defense lawyer Julie Clark said that these new jurors are "much more trusting of police." Another lawyer, Arthur Aidala said:

Now, the grand juries have more law-and-order types in there. ... People who can afford to live in Brooklyn now don't have the experience of police officers throwing them against cars and searching them. A person who just moves here from Wisconsin or Wyoming, they can't relate to [that]. It doesn't sound credible to them.[89]

Brooklyn district attorney Kenneth P. Thompson had argued that most people don't understand how summons court operates, resulting in missed court dates and automatic bench warrants; that the omission of race and ethnicity information on the summons form should be remedied, to provide statistics of summons recipients; that poor access to public defenders by indigent persons in summons courts raises serious due process concerns; and that the city needs to overhaul its summons system, to handle quality-of-life infractions better and in a timely manner.[41]

History

[edit]The New York City Court of Special Sessions was created in 1744, from a court created in 1732.[90][91] (The New York County Court of General Sessions tried felonies as a county court, whereas Bronx, Kings, Queens, and Richmond counties had a regular County Court.[92][93]) In 1848 the city Police Courts or Magistrates' Courts were created, elected within six districts.[94] In 1910 both city courts were reconstituted after the city's consolidation.[95] The Court of Special Sessions tried misdemeanors like other cities' police courts, and the Magistrates' Courts tried petty criminal cases.[92]

The Criminal Court was established effective 1 September 1962 by the New York City Criminal Court Act of the 173rd New York State Legislature and Governor Nelson Rockefeller, replacing the City Magistrates' Courts and the Court of Special Sessions.[96] (The work and personnel of the New York County Court of General Sessions, and the County Court in Bronx, Kings, Queens, and Richmond counties, were transferred to the Supreme Court.)

In 1969–1970, extrajudicial administrative courts were created to offload a large volume of cases from the Criminal Court: the state DMV Traffic Violations Bureau (TVB), which adjudicates non-parking traffic violations, and the city DOF Parking Violations Bureau, which adjudicates parking violations.[97][98] Though the state had created Narcotics Parts (N Parts) in the city's Supreme Court in 1971,[99] in 1993 the Criminal Court implemented its first problem-solving court in the Midtown Community Court.[100]

Manhattan courthouse

[edit]The Criminal Courthouse building is a 17-story Art Deco-style building at 100 Centre Street in lower Manhattan designed by Wiley Corbett and Charles B. Meyers, and constructed from 1938-41. It was built on the site of the 1894 Criminal Courthouse and the original Tombs prison.[101]

In popular culture

[edit]The 1980's sitcom Night Court was inspired by the evening court sessions held in the Criminal Courthouse building in Manhattan from 5:00 pm to 1:00 am; however, the exterior of the New York County Courthouse is shown in the show's opening sequence.

Tourists sometimes view the evening sessions from the public galleries.[102][103]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b The New York State Courts: An Introductory Guide (PDF). New York State Office of Court Administration. 2000. p. 4. OCLC 68710274. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ^ The New York State Courts: An Introductory Guide (PDF). New York State Office of Court Administration. 2010. p. 2. OCLC 668081412. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-08-17.

- ^ New York City Criminal Court Act § 20

- ^ a b "Administration of The Unified Court System". New York State Office of Court Administration. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m NYCBA and NYCLA 1993.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Ronald (27 April 1990). "Judge Orders Arraignments In 24 Hours". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Sack, Kevin (27 March 1991). "Ruling Forces New York to Release Or Arraign Suspects in 24 Hours". The New York Times.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Criminal Procedure Law § 150.10 et seq.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin (November 26, 2002). "Same Walk, Nicer Shoes; Parading of Executives in Custody Fuels New Debate". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2011.

- ^ Tierney, John (October 30, 1994). "THE BIG CITY; Walking the Walk". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Harden, Blaine (February 27, 1999). "Parading of Suspects Is Evolving Tradition; Halted After a Judge's Ruling, 'Perp Walks' Are Likely to Be Revived—in Some Form". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (May 19, 2011). "An American Rite: Suspects on Parade (Bring a Raincoat)". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ Saulny, Susan (20 April 2003). "No Objections as Manhattan Late Night Court Recesses for Good". The New York Times.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, pp. 17–18.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, p. 19.

- ^ a b Merkl, Taryn (16 April 2020). "New York's Latest Bail Law Changes Explained". Brennan Center for Justice. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ^ a b The Editorial Board (11 May 2016). "A Nightmare Court, Worthy of Dickens". The New York Times.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, p. 20,32.

- ^ Schreibersdorf, Lisa (17 June 2015), BDS Testifies at NYC Council Oversight Hearing on New York's Bail System and the Need for Reform (PDF), Brooklyn Defender Services, p. 3

- ^ Max, Samantha (8 January 2025). "Law Meant to Make Bail More Affordable in New York Isn't Working, Report Finds". Gothamist. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Criminal Procedure Law § 180.80

- ^ Barry, Justin A. (10 December 2015), Memorandum Re Bail Review (PDF), retrieved 2022-08-28 – via Kings County Criminal Bar Association

- ^ McKinley Jr., James C. (October 1, 2015). "State's Chief Judge, Citing 'Injustice,' Lays Out Plans to Alter Bail System". The New York Times.

- ^ Keshner, Andrew (December 14, 2015). "Misdemeanor Bail Reviews Beginning in New York City". New York Law Journal.

- ^ a b NYCLA 2011, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Criminal Procedure Law § 30.30

- ^ a b c Annual Report 2013, p. 37.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, pp. 67–71.

- ^ a b c Annual Report 2013, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Ryley, Sarah; Bult, Laura; Gregorian, Dareh (4 August 2014). "Daily News analysis finds racial disparities in summonses for minor violations in 'broken windows' policing". New York Daily News.

- ^ a b Youth Represent. "Proposed Pro Bono Opportunity Between MoFo and Youth Represent" (PDF). Equal Justice Works. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ a b Wallace, Jonathan (May 2015), "Poor People's Courts", The Ethical Spectical

- ^ The Committee on Courts of Appellate Jurisdiction of the New York State Bar Association. New York's Appellate Terms: A Manual for Practitioners. New York State Bar Association. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ^ a b c d People v. Vial, 132 Misc.2d 5 (1986)

- ^ Annual Report 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Staples, Brent (16 June 2012). "Inside the Warped World of Summons Court". The New York Times.

- ^ Goldstein, Joseph (9 November 2014). "Marijuana May Mean Ticket, Not Arrest, in New York City". The New York Times.

- ^ Baker, Al (10 November 2014). "Concerns in Criminal Justice System as New York City Eases Marijuana Policy". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Thompson, Kenneth P. (21 November 2014). "Will Pot Pack New York's Courts?". The New York Times.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, p. 4.

- ^ a b Pinto, Nick (November 3, 2016). "Protesters Sue to Stop NYPD from Acting as Prosecutors". The Village Voice.

- ^ "Problem Solving Courts Overview". New York State Office of Court Administration. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "New York City Criminal Court - Special Projects". New York State Office of Court Administration. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

The Midtown Community Court, part of the Criminal Court of the City of New York, arraigns defendants who are arrested in Times Square, Clinton and Chelsea areas of the city and charged with any non-felony offense.

- ^ a b Annual Report 2013, p. 53.

- ^ Pakes, Francis; Winstone, Jane (2013). "Community justice: the smell of fresh bread". Community Justice: Issues for probation and criminal justice. Willan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84392-128-8.

- ^ a b c Annual Report 2013, p. 47.

- ^ Annual Report 2013, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c d Annual Report 2013, p. 42.

- ^ a b "Court Administration". New York State Office of Court Administration. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Court Administration - Local Administrators". New York State Office of Court Administration. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ NYS Executive Department (24 April 1962), "Form B-201 Budget Report on Bills", New York State bill jackets - L-1962-CH-0697, New York State Library

- ^ NYS Senate Standing Committee on Judiciary (21 February 2024). 2023 Judiciary Committee Annual Report (Report). New York State Senate.

- ^ NYS Assembly Standing Committee on Judicary (15 December 2022). 2022 Annual Report of the New York State Standing Committee on Judiciary (Report). New York State Assembly.

- ^ a b c New York City Bar Association Special Committee to Encourage Judicial Service (2012). How To Become a Judge (PDF). New York City Bar Association. pp. 3–6.

- ^ New York City Criminal Court Act § 22(2)

- ^ New York City Bar Association Council on Judicial Administration (March 2014). Judicial Selection Methods in the State of New York: A Guide to Understanding and Getting Involved in the Selection Process (PDF). New York City Bar Association. pp. 9–10, 12, 13.

- ^ Trangle, Sarina (March 1, 2016). "Council presses de Blasio administration to reduce delays in criminal court". City & State.

- ^ a b Lancman, Rory (February 24, 2016). "We Need Speedy Trial Reform in City's Criminal Courts". New York Law Journal. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Alt URL

- ^ Judiciary Law article 22. Criminal Procedure Law § 350.20, 255.20. Vehicle and Traffic Law § 1690.

- ^ NYCLA 2011, pp. 3, 6.

- ^ "Caseload and Trial Capacity Issues in the Criminal Court of the City of New York" (PDF), The Record of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, vol. 54, no. 6, p. 771, 1999

- ^ 22 NYCRR part 122

- ^ NYCLA 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Yakin, Heather (14 October 2014). "Upstate trial could change course for defense of poor". Times Herald-Record.

- ^ Wright, Eisha N. (27 March 2015). Report on the Fiscal 2016 Preliminary Budget: Courts and Legal Aid Society / Indigent Defense Services (PDF). New York City Council Finance Division.

- ^ Feuer, Alan (20 May 2011). "The Defense Can't Afford to Rest". The New York Times.

- ^ People v Jeffreys, 53 Misc 3d 1205 (2016)

- ^ Jacobs, Shayna (19 September 2016). "Judge: NYPD can act as prosecutor in Black Lives Matter cases". New York Daily News.

- ^ Dolmetsch, Chris (14 December 2011). "Occupy Wall Street Judge Refuses to Throw Out Summonses". Bloomberg News.

- ^ McKinley Jr., James C. (19 March 2014). "New York Courts Cut Time Between Arrest and Arraignment". The New York Times.

- ^ Glaberson, William (15 April 2013). "Courts in Slow Motion, Aided by the Defense". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ Glaberson, William (16 April 2013). "For 3 Years After Killing, Evidence Fades as a Suspect Sits in Jail". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ a b Glaberson, William (1 May 2013). "Even for Minor Crimes in Bronx, No Guarantee of Getting a Trial". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ Glaberson, William (14 April 2013). "Waiting Years for Day in Court". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ Weiser, Benjamin; McKinley Jr., James (May 10, 2016). "Chronic Bronx Court Delays Deny Defendants Due Process, Suit Says". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Buettner, Russ (5 February 2013). "Top Judge Says Bail in New York Isn't Safe or Fair". The New York Times.

- ^ Criminal Procedure Law § 520.10

- ^ a b Pinto, Nick (25 April 2012). "Bail is Busted: How Jail Really Works". The Village Voice.

- ^ The Editorial Board (10 July 2015). "Trapped by New York's Bail System". The New York Times.

- ^ "New York City: Bail Penalizes the Poor: Thousands Accused of Minor Crimes Spend Time in Pretrial Detention". Human Rights Watch. 3 December 2010.

- ^ Fellner, Jamie (2010). The Price of Freedom: Bail and Pretrial Detention of Low Income Nonfelony Defendants in New York City. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-56432-718-5.

- ^ McKinley Jr., James C. (8 July 2014). "Study Finds Racial Disparity in Criminal Prosecutions". The New York Times.

- ^ Gonnerman, Jennifer (6 October 2014). "Before the Law". The New Yorker.

- ^ "Accused of Stealing a Backpack, High School Student Jailed for Nearly Three Years Without Trial". Democracy Now!. 1 October 2014.

- ^ Brooklyn Defender Services (8 August 2015), Memorandum of Support: S5988 (Squadron) / A7841 (Aubry) 'Kalief's Law' (PDF),

It is an open secret that prosecutors use pre-trial detention to extract plea agreements involving admissions of guilt from defendants.

- ^ Feldman & Bloustein 2016, p. 84.

- ^ Saul, Josh (16 June 2014). "When Brooklyn juries gentrify, defendants lose". New York Post.

- ^ "An Act for the Speedy Punishing & Releasing Such persons from Imprisonment as Shall Commit any Criminal Offences in the City and County of New York under the Degree of Grand Larceny". The Colonial Laws of New York from the Year 1664 to the Revolution. Vol. 3. 1894. pp. 379–381. hdl:2027/umn.319510021585399. LCCN 28028259. Chapter 767 of Livingston & Smith and Van Schaack, enacted 1 September 1744.

- ^ New York City Board of Aldermen (1911). Proceedings of the Board of Aldermen of the City of New York from January 2 to March 28, 1911. Vol. 1. p. 793.

- ^ a b Boynton, Frank David (1918). Actual Government of New York: A Manual of the Local, Municipal, State and Federal Government for Use in Public and Private Schools of New York State. Ginn and Company. pp. 68–71.

- ^ "Suggestions for Relieving Congestion in the Criminal Courts of New York City". The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. Vol. 13: May 1922–February 1923. Northwestern University Press. 1922. pp. 127–135.

- ^ "An Act in relation to Justices and Police Courts in the city of New York". Laws of New York. Vol. 71st sess. 1848. pp. 249–252. hdl:2027/uc1.b4375252. ISSN 0892-287X. Chapter 153, enacted 30 March 1848, effective immediately.

- ^ "Inferior Criminal Courts Act of the City of New York". Laws of New York. Vol. 133rd sess.: II. 1910. pp. 1774–1821. hdl:2027/uc1.b4375313. ISSN 0892-287X. Chapter 659, enacted 25 June 1910, effective immediately.

- ^ Criminal Court Act.

- ^ NYS Executive Department (26 May 1969), New York State bill jackets - L-1969-CH-1074, New York State Library

- ^ Zimmerman, Joseph F. (2008). The Government and Politics of New York State (2nd ed.). SUNY Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-7914-7435-8.

- ^ Chapter 462 of the Laws of 1971, volume 2, pages 1341–1344, enacted 17 June 1971.

- ^ Kaye, Judith (2019). Judith S. Kaye in Her Own Words: Reflections on Life and the Law, with Selected Judicial Opinions and Articles. State University of New York Press. pp. 64–66, 451. ISBN 9781438474816. LCCN 2018033290.

- ^ "Manhattan Criminal Courthouse - Department of Citywide Administrative Services". www.nyc.gov. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ "night court is the weirdest tourist attraction in NYC, and the world". The Tab US. 2016-07-21. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ "Is Night Court a Real Thing?". NBC Insider Official Site. 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

General and cited references

[edit]- "The New York City Criminal Court Act". Laws of New York. Vol. 185th sess.: III. 1962. pp. 3266–3291. hdl:2027/uc1.b4378119. ISSN 0892-287X. Chapter 697, enacted 24 April 1962, effective 1 September 1962. Senate Bill, Introductory Number 3716, Printed Number 4674.

- Criminal Court of the City of New York: Annual Report 2013 (PDF). Office of the Chief Clerk of New York City Criminal Court. July 2014.

- Joint Committee of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York and the New York County Lawyers' Association (c. 1993). Criminal Justice System Handbook. New York State Unified Court System. OCLC 669176295.

- New York County Lawyers' Association (2011). New York City Criminal Courts Manual. New York County Lawyers' Association. ISBN 978-1-105-20162-2.

External links

[edit]- Legal Referral Service (a lawyer referral service) from the New York City Bar Association

- New York City Criminal Court official webpage on the New York State Unified Court System website

- Inmate Lookup Service of the NYCDOC