Discrete mathematics

| Part of a series on | ||

| Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

|

| ||

Discrete mathematics is the study of mathematical structures that can be considered "discrete" (in a way analogous to discrete variables, having a bijection with the set of natural numbers) rather than "continuous" (analogously to continuous functions). Objects studied in discrete mathematics include integers, graphs, and statements in logic.[1][2][3] By contrast, discrete mathematics excludes topics in "continuous mathematics" such as real numbers, calculus or Euclidean geometry. Discrete objects can often be enumerated by integers; more formally, discrete mathematics has been characterized as the branch of mathematics dealing with countable sets[4] (finite sets or sets with the same cardinality as the natural numbers). However, there is no exact definition of the term "discrete mathematics".[5]

The set of objects studied in discrete mathematics can be finite or infinite. The term finite mathematics is sometimes applied to parts of the field of discrete mathematics that deals with finite sets, particularly those areas relevant to business.

Research in discrete mathematics increased in the latter half of the twentieth century partly due to the development of digital computers which operate in "discrete" steps and store data in "discrete" bits. Concepts and notations from discrete mathematics are useful in studying and describing objects and problems in branches of computer science, such as computer algorithms, programming languages, cryptography, automated theorem proving, and software development. Conversely, computer implementations are significant in applying ideas from discrete mathematics to real-world problems.

Although the main objects of study in discrete mathematics are discrete objects, analytic methods from "continuous" mathematics are often employed as well.

In university curricula, discrete mathematics appeared in the 1980s, initially as a computer science support course; its contents were somewhat haphazard at the time. The curriculum has thereafter developed in conjunction with efforts by ACM and MAA into a course that is basically intended to develop mathematical maturity in first-year students; therefore, it is nowadays a prerequisite for mathematics majors in some universities as well.[6][7] Some high-school-level discrete mathematics textbooks have appeared as well.[8] At this level, discrete mathematics is sometimes seen as a preparatory course, like precalculus in this respect.[9]

The Fulkerson Prize is awarded for outstanding papers in discrete mathematics.

Topics

[edit]Theoretical computer science

[edit]

Theoretical computer science includes areas of discrete mathematics relevant to computing. It draws heavily on graph theory and mathematical logic. Included within theoretical computer science is the study of algorithms and data structures. Computability studies what can be computed in principle, and has close ties to logic, while complexity studies the time, space, and other resources taken by computations. Automata theory and formal language theory are closely related to computability. Petri nets and process algebras are used to model computer systems, and methods from discrete mathematics are used in analyzing VLSI electronic circuits. Computational geometry applies algorithms to geometrical problems and representations of geometrical objects, while computer image analysis applies them to representations of images. Theoretical computer science also includes the study of various continuous computational topics.

Information theory

[edit]

Information theory involves the quantification of information. Closely related is coding theory which is used to design efficient and reliable data transmission and storage methods. Information theory also includes continuous topics such as: analog signals, analog coding, analog encryption.

Logic

[edit]Logic is the study of the principles of valid reasoning and inference, as well as of consistency, soundness, and completeness. For example, in most systems of logic (but not in intuitionistic logic) Peirce's law (((P→Q)→P)→P) is a theorem. For classical logic, it can be easily verified with a truth table. The study of mathematical proof is particularly important in logic, and has accumulated to automated theorem proving and formal verification of software.

Logical formulas are discrete structures, as are proofs, which form finite trees[10] or, more generally, directed acyclic graph structures[11][12] (with each inference step combining one or more premise branches to give a single conclusion). The truth values of logical formulas usually form a finite set, generally restricted to two values: true and false, but logic can also be continuous-valued, e.g., fuzzy logic. Concepts such as infinite proof trees or infinite derivation trees have also been studied,[13] e.g. infinitary logic.

Set theory

[edit]Set theory is the branch of mathematics that studies sets, which are collections of objects, such as {blue, white, red} or the (infinite) set of all prime numbers. Partially ordered sets and sets with other relations have applications in several areas.

In discrete mathematics, countable sets (including finite sets) are the main focus. The beginning of set theory as a branch of mathematics is usually marked by Georg Cantor's work distinguishing between different kinds of infinite set, motivated by the study of trigonometric series, and further development of the theory of infinite sets is outside the scope of discrete mathematics. Indeed, contemporary work in descriptive set theory makes extensive use of traditional continuous mathematics.

Combinatorics

[edit]Combinatorics studies the ways in which discrete structures can be combined or arranged. Enumerative combinatorics concentrates on counting the number of certain combinatorial objects - e.g. the twelvefold way provides a unified framework for counting permutations, combinations and partitions. Analytic combinatorics concerns the enumeration (i.e., determining the number) of combinatorial structures using tools from complex analysis and probability theory. In contrast with enumerative combinatorics which uses explicit combinatorial formulae and generating functions to describe the results, analytic combinatorics aims at obtaining asymptotic formulae. Topological combinatorics concerns the use of techniques from topology and algebraic topology/combinatorial topology in combinatorics. Design theory is a study of combinatorial designs, which are collections of subsets with certain intersection properties. Partition theory studies various enumeration and asymptotic problems related to integer partitions, and is closely related to q-series, special functions and orthogonal polynomials. Originally a part of number theory and analysis, partition theory is now considered a part of combinatorics or an independent field. Order theory is the study of partially ordered sets, both finite and infinite.

Graph theory

[edit]

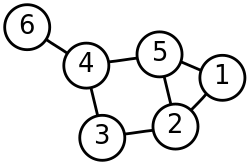

Graph theory, the study of graphs and networks, is often considered part of combinatorics, but has grown large enough and distinct enough, with its own kind of problems, to be regarded as a subject in its own right.[14] Graphs are one of the prime objects of study in discrete mathematics. They are among the most ubiquitous models of both natural and human-made structures. They can model many types of relations and process dynamics in physical, biological and social systems. In computer science, they can represent networks of communication, data organization, computational devices, the flow of computation, etc. In mathematics, they are useful in geometry and certain parts of topology, e.g. knot theory. Algebraic graph theory has close links with group theory and topological graph theory has close links to topology. There are also continuous graphs; however, for the most part, research in graph theory falls within the domain of discrete mathematics.

Number theory

[edit]

Number theory is concerned with the properties of numbers in general, particularly integers. It has applications to cryptography and cryptanalysis, particularly with regard to modular arithmetic, diophantine equations, linear and quadratic congruences, prime numbers and primality testing. Other discrete aspects of number theory include geometry of numbers. In analytic number theory, techniques from continuous mathematics are also used. Topics that go beyond discrete objects include transcendental numbers, diophantine approximation, p-adic analysis and function fields.

Algebraic structures

[edit]Algebraic structures occur as both discrete examples and continuous examples. Discrete algebras include: Boolean algebra used in logic gates and programming; relational algebra used in databases; discrete and finite versions of groups, rings and fields are important in algebraic coding theory; discrete semigroups and monoids appear in the theory of formal languages.

Discrete analogues of continuous mathematics

[edit]There are many concepts and theories in continuous mathematics which have discrete versions, such as discrete calculus, discrete Fourier transforms, discrete geometry, discrete logarithms, discrete differential geometry, discrete exterior calculus, discrete Morse theory, discrete optimization, discrete probability theory, discrete probability distribution, difference equations, discrete dynamical systems, and discrete vector measures.

Calculus of finite differences, discrete analysis, and discrete calculus

[edit]In discrete calculus and the calculus of finite differences, a function defined on an interval of the integers is usually called a sequence. A sequence could be a finite sequence from a data source or an infinite sequence from a discrete dynamical system. Such a discrete function could be defined explicitly by a list (if its domain is finite), or by a formula for its general term, or it could be given implicitly by a recurrence relation or difference equation. Difference equations are similar to differential equations, but replace differentiation by taking the difference between adjacent terms; they can be used to approximate differential equations or (more often) studied in their own right. Many questions and methods concerning differential equations have counterparts for difference equations. For instance, where there are integral transforms in harmonic analysis for studying continuous functions or analogue signals, there are discrete transforms for discrete functions or digital signals. As well as discrete metric spaces, there are more general discrete topological spaces, finite metric spaces, finite topological spaces.

The time scale calculus is a unification of the theory of difference equations with that of differential equations, which has applications to fields requiring simultaneous modelling of discrete and continuous data. Another way of modeling such a situation is the notion of hybrid dynamical systems.

Discrete geometry

[edit]Discrete geometry and combinatorial geometry are about combinatorial properties of discrete collections of geometrical objects. A long-standing topic in discrete geometry is tiling of the plane.

In algebraic geometry, the concept of a curve can be extended to discrete geometries by taking the spectra of polynomial rings over finite fields to be models of the affine spaces over that field, and letting subvarieties or spectra of other rings provide the curves that lie in that space. Although the space in which the curves appear has a finite number of points, the curves are not so much sets of points as analogues of curves in continuous settings. For example, every point of the form for a field can be studied either as , a point, or as the spectrum of the local ring at (x-c), a point together with a neighborhood around it. Algebraic varieties also have a well-defined notion of tangent space called the Zariski tangent space, making many features of calculus applicable even in finite settings.

Discrete modelling

[edit]In applied mathematics, discrete modelling is the discrete analogue of continuous modelling. In discrete modelling, discrete formulae are fit to data. A common method in this form of modelling is to use recurrence relation. Discretization concerns the process of transferring continuous models and equations into discrete counterparts, often for the purposes of making calculations easier by using approximations. Numerical analysis provides an important example.

Challenges

[edit]

The history of discrete mathematics has involved a number of challenging problems which have focused attention within areas of the field. In graph theory, much research was motivated by attempts to prove the four color theorem, first stated in 1852, but not proved until 1976 (by Kenneth Appel and Wolfgang Haken, using substantial computer assistance).[15]

In logic, the second problem on David Hilbert's list of open problems presented in 1900 was to prove that the axioms of arithmetic are consistent. Gödel's second incompleteness theorem, proved in 1931, showed that this was not possible – at least not within arithmetic itself. Hilbert's tenth problem was to determine whether a given polynomial Diophantine equation with integer coefficients has an integer solution. In 1970, Yuri Matiyasevich proved that this could not be done.

The need to break German codes in World War II led to advances in cryptography and theoretical computer science, with the first programmable digital electronic computer being developed at England's Bletchley Park with the guidance of Alan Turing and his seminal work, On Computable Numbers.[16] The Cold War meant that cryptography remained important, with fundamental advances such as public-key cryptography being developed in the following decades. The telecommunications industry has also motivated advances in discrete mathematics, particularly in graph theory and information theory. Formal verification of statements in logic has been necessary for software development of safety-critical systems, and advances in automated theorem proving have been driven by this need.

Computational geometry has been an important part of the computer graphics incorporated into modern video games and computer-aided design tools.

Several fields of discrete mathematics, particularly theoretical computer science, graph theory, and combinatorics, are important in addressing the challenging bioinformatics problems associated with understanding the tree of life.[17]

Currently, one of the most famous open problems in theoretical computer science is the P = NP problem, which involves the relationship between the complexity classes P and NP. The Clay Mathematics Institute has offered a $1 million USD prize for the first correct proof, along with prizes for six other mathematical problems.[18]

See also

[edit]- Outline of discrete mathematics

- Cyberchase, a show that teaches discrete mathematics to children

References

[edit]- ^ Richard Johnsonbaugh, Discrete Mathematics, Prentice Hall, 2008.

- ^ Franklin, James (2017). "Discrete and continuous: a fundamental dichotomy in mathematics" (PDF). Journal of Humanistic Mathematics. 7 (2): 355–378. doi:10.5642/jhummath.201702.18. S2CID 6945363. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Discrete Structures: What is Discrete Math?". cse.buffalo.edu. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ Biggs, Norman L. (2002), Discrete mathematics, Oxford Science Publications (2nd ed.), The Clarendon Press Oxford University Press, p. 89, ISBN 9780198507178, MR 1078626,

Discrete Mathematics is the branch of Mathematics in which we deal with questions involving finite or countably infinite sets.

- ^ Hopkins, Brian, ed. (2009). Resources for Teaching Discrete Mathematics: Classroom Projects, History Modules, and Articles. Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 978-0-88385-184-5.

- ^ Levasseur, Ken; Doerr, Al. Applied Discrete Structures. p. 8.

- ^ Geoffrey Howson, Albert, ed. (1988). Mathematics as a Service Subject. Cambridge University Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-521-35395-3.

- ^ Rosenstein, Joseph G. Discrete Mathematics in the Schools. American Mathematical Society. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-8218-8578-9.

- ^ "UCSMP". uchicago.edu.

- ^ Troelstra, A.S.; Schwichtenberg, H. (2000-07-27). Basic Proof Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-521-77911-1.

- ^ Buss, Samuel R. (1998). Handbook of Proof Theory. Elsevier. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-444-89840-1.

- ^ Baader, Franz; Brewka, Gerhard; Eiter, Thomas (2001-10-16). KI 2001: Advances in Artificial Intelligence: Joint German/Austrian Conference on AI, Vienna, Austria, September 19-21, 2001. Proceedings. Springer. p. 325. ISBN 978-3-540-42612-7.

- ^ Brotherston, J.; Bornat, R.; Calcagno, C. (January 2008). "Cyclic proofs of program termination in separation logic". ACM SIGPLAN Notices. 43 (1): 101–112. doi:10.1145/1328897.1328453.

- ^ Mohar, Bojan; Thomassen, Carsten (2001). Graphs on Surfaces. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6689-0. OCLC 45102952.

- ^ a b Wilson, Robin (2002). Four Colors Suffice. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-691-11533-7.

- ^ Hodges, Andrew (1992). Alan Turing: The Enigma. Random House.

- ^ Hodkinson, Trevor R.; Parnell, John A. N. (2007). Reconstruction the Tree of Life: Taxonomy And Systematics of Large And Species Rich Taxa. CRC Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8493-9579-6.

- ^ "Millennium Prize Problems". 2000-05-24. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

Further reading

[edit]- Biggs, Norman L. (2002). Discrete Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850717-8.

- Dwyer, John (2010). An Introduction to Discrete Mathematics for Business & Computing. Algana Pub. ISBN 978-1-907934-00-1.

- Epp, Susanna S. (2010-08-04). Discrete Mathematics With Applications. Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-495-39132-6.

- Graham, Ronald; Knuth, Donald E.; Patashnik, Oren (1994). Concrete Mathematics (2nd ed.). Addison–Wesley. ISBN 0-201-55802-5.

- Grimaldi, Ralph P. (2004). Discrete and Combinatorial Mathematics: An Applied Introduction. Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-72634-3.

- Knuth, Donald E. (2011). The Art of Computer Programming. Vol. 1–4a Boxed Set. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-75104-1.

- Matoušek, Jiří; Nešetřil, Jaroslav (1998). Discrete Mathematics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850208-1.

- Obrenic, Bojana (2003). Practice Problems in Discrete Mathematics. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-045803-2.

- Rosen, Kenneth H.; Michaels, John G. (2000). Hand Book of Discrete and Combinatorial Mathematics. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0149-0.

- Rosen, Kenneth H. (2007). Discrete Mathematics: And Its Applications. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-288008-3.

- Simpson, Andrew (2002). Discrete Mathematics by Example. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-709840-7.

External links

[edit]- Discrete mathematics Archived 2011-08-29 at the Wayback Machine at the utk.edu Mathematics Archives, providing links to syllabi, tutorials, programs, etc.

- Iowa Central: Electrical Technologies Program Discrete mathematics for Electrical engineering.

![{\displaystyle V(x-c)\subset \operatorname {Spec} K[x]=\mathbb {A} ^{1}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/147df15a1780a002602cd26438adbec315699e2b)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {Spec} K[x]/(x-c)\cong \operatorname {Spec} K}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/80cc3220b7c86e6d0862f1bcf3fbac3ffc0191a7)

![{\displaystyle \operatorname {Spec} K[x]_{(x-c)}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/76e6e66e203e1805ec5b90fa25d9f0c817f28dd7)