Div (mythology)

| |

| Grouping | Mythical creature |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Persian mythology Armenian mythology Albanian mythology Turkish mythology |

| Country | Iran, Armenia, Albania, Turkey |

Div or dev (Classical Persian: دیو dēw; Iranian Persian: دیو dīv) (with the broader meaning of demons or fiends) are monstrous creatures within Middle Eastern lore, and probably Persian origin.[1] Most of their depictions derive from Persian mythology, integrated to Islam and spread to surrounding cultures including Armenia, Turkic countries[2] and Albania.[3] Despite their Persian origins, they have been adapted according to the beliefs of Islamic concepts of otherworldly entities.[4](pp 37) Although they are not explicitly mentioned within canonical Islamic scriptures, their existence was well accepted by most Muslims just like that of other supernatural creatures.[5](p 34) They exist along with jinn, parī (fairies)[6] and shaitan (devils) within South and Central Asian demon-beliefs.[7]

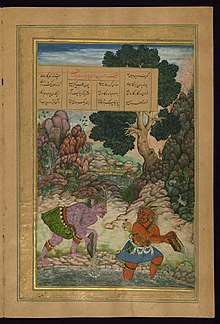

They are described as having a body like that of a human, only of gigantic size, with two horns upon their heads and teeth like the tusks of a boar. Powerful, cruel and cold-hearted, they have a particular relish for the taste of human flesh.[8][full citation needed] Some use only primitive weapons, such as stones: others, more sophisticated, are equipped like warriors, wearing armour and using weapons of metal. Despite their uncouth appearance – and in addition to their great physical strength – many are also masters of sorcery, capable of overcoming their enemies by magic and afflicting them with nightmares.[9]

Their origin is disputed, although it may lie in the Vedic deities (devas) who were later demonized in the Persian religion (see daeva). In Ferdowsi's tenth-century Shahnameh, they are already the evil entities endowed with roughly human shape and supernatural powers familiar from later folklore, in which the divs are described as ugly demons with supernatural strength and power, who, nonetheless, may sometimes be subdued and forced to do the bidding of a sorcerer.

Terminology and relation to other spirits

[edit]The divs are often confused with jinn.[9] Some academics proposed div is simply the Persian term for jinn. However, this poses a problem, because the two terms are not synonymous. While the divs are considered evil, the jinn have free will and are morally ambivalent or even benevolent.[5](p 519) Others argue that the term jinn refers to all kinds of spiritual entities, including both benevolent and evil creatures. In early Persian translations of the Quran, when the term jinn was used to refer to evil spirits, they have been interpreted as divs sometimes.[10]

In other works, such as People of the Air, the div are explicitly distinguished from jinn.[11](p 148) In some cases, the term div is juxtaposed to the terms ifrit, shaitan (devil), and taghut (idol), all some sort of demons in Islamic belief, indicating a relationship between those beings but distinct from the (regular) jinn.[12] In Abu Ali Bal'ami's account, the div are used interchangeable with marid, a type of devil which assaults the heavens in an attempt to steal news from the angels.[4](pp 41–42) The term marid is likewise confused with ifrit, in some works, like the standard MacNaghten edition of One Thousand and One Nights.[13]

History

[edit]

The divs seem to have originally been Persian, pre-Zoroastrian, divine or semi-divine beings who were subsequently demonized. By the time of the Islamic conquest, they had faded into Persian folklore and folktales, and hence disseminated throughout the Islamic world. They were modified during that dissemination to include foreign (specifically Hindu) deities, and elements already present in local folklore.

Origins

[edit]

Divs probably originate from the Avestan daevas, deities who share the same origin with Indian Deva (gods). It is unknown when and why the former deities turned into rejected gods or even demons.

Zoroastrianism

[edit]

In the Gathas, the oldest Zorastrian text, they are not yet the evil creatures they will become, although, according to some scholarly interpretations, the texts do indicate that they should be rejected.[14][a]

First known opposition

[edit]Evident from Xph inscriptions, Xerxes I (reigned 486–465 BCE) ordered the destruction of a sanctuary dedicated to Daivas and proclaimed that the Daeva shall not be worshipped.[15] Therefore, first opposition of Daeva must be during or before the reign of Xerxes.

However, the original relation between Daeva and Persian religion remains up to debate. There might have been a pantheon with several types of deities, but while the Indians demonized the Asura and deified the Deva, the Persians demonized the Deva, but deified Asura in the form of Ahura Mazda.[16]

Middle persian era

[edit]In Middle Persian texts, they are already regarded as equivalent to demons. They are created by Ahriman (the devil) along with sorcerers and everything else that is evil. They roam the earth at night and bring people to ruin. During the advent of Islam in Persia, the term was used for both demonized humans and evil supernatural creatures. In the translations of Tabari's Tafsir, the term div was used to designate evil jinn, devils and Satan.[17]

Although the term dew (Middle Persian for div) is not attested in the Babylonian Talmud, they are mentioned in Jewish Babylonian Aramaic bowls next to shedim (demi-gods), ruḥot (spirits), mazzikin ("harmers"), and "satans".[18][19] The exact differences between these entities are, however, not always clear.[20] Asmodeus is designated as the king of both shedim and devs.[21]

Dissemination into the wider Islamic world

[edit]From this Persian origin, belief in div entered Muslim belief. Abu Ali Bal'ami's work on the history of the world, is the oldest known writing including explicitly Islamic cosmology and the div. He attributes his account on the creation of the world to Wahb ibn Munabbih.[4](p40)

Some divs appear to be considered the incarnation of (false) Indian deities, who, unlike jinn, refused to obey the Prophet Solomon.[22]

Evident from the epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE, that, by his day the div had become associated with the people of the Mazandaran of legend (which is not to be identified with the Iranian province of Mazandaran).[9]

While some div appear as supernatural sorcerers, many div appear to be clearly demonized humans, including black people, attributed with supernatural strength, but no supernatural bodily features. Some people continued to worship div in their rituals during the early Islamic period, known as "Daevayasna", although probably out of fear.[23][full citation needed] People of Mazdaran might have been associated with such worship and therefore equated with these entities. Despite many div that appear human in nature, there are also clearly supernatural div, like the white div, who is said to be as huge as a mountain.

Muslim texts

[edit]

Div (demons or fiends) are the former masters of the world, dispossessed yet not extinguished, they are banished far away from the human realm. They occupy a liminal place both spatial and ontological, between the physical and the metaphysical world.[4](p 41) The souls of wicked people could also turn into a demon (div) after death, as evident from Al-Razi[24] an idea recalling the concept of original daeva.[25] His idea comes from the assumption that after death, the desire of the soul remains and that a soul thus turns back to the world in an ugly and demonic shape. His view has frequently been criticized by other Muslim authors.[26]

Throughout many legends they appear as villains, sorcerers, monsters, ogres, or even helpers of the protagonist. It is usually necessary to overcome the div to get his aid. After defeating the div, one must attach a horseshoe, a needle or an iron ring on his body to enslave them.

On the other hand, a div can not be killed by physical combat, even if their body parts are cut off. Instead, one is required to find the object storing the soul of the div: After that object is destroyed, the div is said to disappear in smoke or thin air. The notion of a demon tied to a physical object, later inspired the European genie.[27]

Sometimes they are referred to as maradah.

In the Shahnameh

[edit]The div in the Shahnameh might include both demonic supernatural beings as well as evil humans.[28]

The poem begins with the kings of the Pishdadian dynasty. They defeat and subjugate the demonic divs. Tahmuras commanded the divs and became known as dīvband (binder of demons). Jamshid, the fourth king of the world, ruled over both angels and divs, and served as a high priest of Ahura Mazda (Hormozd). Like his father, he slayed many divs, however, spared some under the condition they teach him new valuable arts, such as writing in different languages.[29] After a just reign over hundreds of years, Jamshid grew haughty and claimed, because of his wealth and power, divinity for himself. Whereupon God withdraws his blessings from him, and his people get unsatisfied with their king. With the ceasing influence of God, the devil gains power and aids Zahhak to usurp the throne.[29] Jamshid dies sawn in two by two demons. Tricked by Ahriman (or Iblis), Zahhak grew two snakes on his shoulders and becomes the demonic serpent-king.[30] The King Kay Kāvus fails to conquer the legendary Mazandaran, the land of divs and gets captured.[31] To save his king, Rustam takes a journey and fights through seven trials. Divs are among the common enemies Rustam faces, the last one the Div-e Sepid, the demonic king of Mazandaran.

Rustam's battle against the demonic may also have a symbolic meaning: Rustam represents wisdom and rationality, fights the demon, embodiment of passion and instinct.[32]: 115 Rustam's victory over the White Div is also a triumph over men's lower drives, and killing the demon is a way to purge the human soul from such evil inclinations. The killing of the White Div is an inevitable act to restore the human king's eyesight.[32]: 115 Eliminating the divs is an act of self-preservation to safeguard the good in oneself's, and the part acceptable in a regulated society.[32]: 115

Origin legends

[edit]Abu Ali Bal'ami reports from Wahb ibn Munabbih that legend it is that god first created the demons (div), then 70,000 years later the fairies (peri), 5000 years later the angels (fereshtegan), and then the jinn. Subsequently, Satan (Iblis) was sent as the arbiter on earth, whereupon he became proud of himself. Thus,Adam was created and given dominion over the earth as the jinn's successor. A similar account is provided by Tabari, who however, omits the existence of fairies and demons, only referring to the jinn as predecessor to mankind, a narration attributed to ibn Abbas.[4](p40)

According to the Süleymanname, the divs were created between the faeries and the jinn, made from the fires of the stars, wind, and smoke; some of them have wings and can fly while others can move quickly.[33]

Edward Smedley (1788–1836) retells Bal'ami's account as an Arabian-Persian legend (not attributed to Bal'ami but to Arabian and Persian authors in general) in greater detail. Accordingly, the jinn were ruled by Jann ibn Jann for 2000 years, before Iblis was sent. After the creation of Adam, Iblis and his angels were sent to hell, along with demons who sided with them. The rest of the demons linger around the surface as a constant threat and test for the faithful. Arab and Persian writers locate their home in Ahriman-abad, the abode of Ahriman the personification of evil and darkness.

The div were manifest (ashkar) and evident (zaher) until the great flood. Afterwards, they became hidden.[4](p 43)

Sufi Literature

[edit]

The term div was still widely used in the adab literature for personifications of vices.[34] They represent the evil urges of the stage to the al-nafs al-ammarah in Sufism.[35] As the sensual soul, they oppose the divine spirit, a motif often reflected in the figure of a div and the prophet Solomon.[36] Attar of Nishapur writes: "If you bind the div, you will set out for the royal pavilion with Solomon" and "You have no command over your self's kingdom [body and mind], for in your case the div is in the place of Solomon".[37]

In Rumi's Masnavi, demons serve as a symbol of pure evil. the existence of demons provide an answer to the question about the existence of evil. He tells a story about an artist who draws both "beautiful houris and ugly demons". Images of demons do not diminish the artists talents, on the opposite, his ability to draw evil in the most grotesque way possible, proves his capabilities. Likewise, when God creates evil, it does not violate but proves his omnipotence. (Masnavī II, 2539–2544; Masnavī II, 2523–2528)[38]

The Kulliyati Chahar Kitab reads as follows to explain the effect of demons on the human soul:[39]

"The desire to give up nafs is weak, the worship of God will weaken nafs.... Anyone who gives up hedonism, he will overcome the oppressive nafs.... If one behaved according to his carnal desire, how could one make jihad [struggle] with nafs. ... The killing of nafs may not be possible except by means of the use of the dagger of silence, the sword of hunger, or the spear of solitude and humility.... If you want to kill the div [demon] of nafs, you must stay away from the haram [forbidden].... If you are a slave of your sexual desire, even if you think you are free, you are a prisoner."

Folklore

[edit]Armenian

[edit]In Armenian mythology and many various Armenian folk tales, the dev (in Armenian: դև) appears both in a kind and specially in a malicious role,[40] and has a semi-divine origin. Dev is a very large being with an immense head on his shoulders, and with eyes as large as earthen bowls.[41][page needed] Some of them may have only one eye. Usually, there are black and white devs. However, both of them can either be malicious or kind.

The White Dev is present in Hovhannes Tumanyan's tale "Yedemakan Tzaghike" (Arm.: Եդեմական Ծաղիկը), translated as "The Flower of Paradise". In the tale, the Dev is the flower's guardian.

Jushkaparik, Vushkaparik, or Ass-Pairika is another chimerical being whose name indicates a half-demoniac and half-animal being, or a Pairika—a female Dev with amorous propensities—that appeared in the form of an ass and lived in ruins.[41][page needed]

In one medieval Armenian lexicon, the dev are explained as rebellious angels.[42]

Persian

[edit]

According to Persian folklore, the divs are inverted creatures, who do the opposite of what has been told to them. They are active at night, but get sleepy at day. Darkness is said to increase their power.[9] Usually, the approach of a div is presaged by a change in temperature or foul smell in the air.[9] They are capable of transformation and performing magic. They are said to capture maidens, trying to force them to marry the div.[9] Some have the form of a snake or a dragon with multiple heads, whose heads grow again, after slain, comparable to the Hydra.[43] In his treatise about the supernatural Ahl-i Hava (people of the air), Ghulam Husayn Sa'idi discusses several folkloric beliefs about different types of supernatural creatures and demons. He describes the Div as tall creatures living far away either on islands or in the desert. With their magical powers, they could turn people into statues by touching them.[11][44]

The divs are in constant battle with benevolent peris (fairies).[45][46] While the divs are usually perceived as male, the peris are often, but not necessarily, depicted as female.[47] According to a story, a man saved a white snake from a black one. The snake later revealed that she was a peri, and the black snake a div, who attacked her. The divs in turn, frequently try to capture the peris and imprison them in cages.

Turkic

[edit]Div in Turkish language refers to a (primordial) giant.[48] According to Deniz Karakurt, they usually feature as elements of fairy-tales as enemies of a hero,[49] but others also identified them in folktales.[50] In such tales, they are associated with Erlik (Lord of the underworld), but unlike Erlik, they can be killed.[51] In some later depictions, they aren't necessarily evil and a hero might turn them into benign and supportive creatures.

In Kazakh fairy-tales, they often capture women, live in caves, and eat human flesh. Many ancient people probably believed such tales to be true, and that places beneath the earth's surface, where no human has gone before, were inhabited by gods and divs.[52] In Tatar folklore, the divs are described as beings living in the depths of the waters under the earth. They may bewitch people or invite them as guests for dinner. They could smell the spirit of humans, whenever they enter their lairs. If one speaks bismillah, all the offered dishes turn into horse droppings and the demon himself disappears.[52]

In Kisekbasch Destani ("Story of the cut head"), a Turkish Sufi legend from the 13th or 14th Century, Ali encounters a beheaded men, whose head is still reciting the Quran. His wife has been captured and his child has been devoured by a div. Ali descends to the underworld to kill the div. Here, he finds out, the div further captured 500 Sunnites and the div threats Ali, to destroy the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and destroy the legacy of Islam. After a battle, Ali manages to kill the div, release the inmates, saves the devoured child and brings the severed head, with aid of Muhammad back to life.[53]

In modern times, the role of the divs are sometimes inverted. Galimyan Gilmanov (2000) drawing from Tatar folklore, reinvents the story of a girl encountering a div in the forest. Here, the div who owns the meadow in the forest is supportive and grants the girl a wish after she offers him her comb.[54]

Occult depictions

[edit]Div appear within Islamic treatises on the occult. Their depictions often invoke the idea of Indian deities or are directly identified with them.[55] To enslave a div, one must pierce their skin with a needle or bind them on iron rings. Another method relies on burning their hair in fire, to summon them.[9] As Solomon enslaved the devils, same is said to be true about the div.

Probably, the legends of the Quran about Solomon are conflated with the legends of the Persian hero Jamshid, who is said to have enslaved the divs.[56] In later Islamic thought, Solomon is said to have bound both devils and the divs to his will, inspiring Middle Eastern magicians trying to also capture such demons.

In some stories, divs are said to be able to bestow magical abilities upon others. Once, a man encountered a div, and the div offered him to learn the ability to speak with animals. However, if the man tells someone about this gift, he will die.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The scope of aēnah- "error" is not precisely understood, and in Yasna 32.3 it is unclear if the association of daeva- with unambiguously negative terms (for example with aka- "evil") formulates a relationship or is the revocation of one. The definitions of Yasna 32.3 occur with a syntactical construct that is otherwise unattested.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Friedl, E. (2020). Religion and Daily Life in the Mountains of Iran: Theology, saints, people. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 85.

- ^ Karakurt, Deniz (2011). Türk Söylence Sözlüğü [Turkish Mythological Dictionary] (PDF). p. 90. ISBN 9786055618032. (OTRS: CC BY-SA 3.0)

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2007). "Albanian Tales". In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Vol. 1: A–F. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 9780313049477. OCLC 1063874626.

- ^ a b c d e f Abedinifard, Mostafa; Azadibougar, Omid; Vafa, Amirhossein, eds. (2021). Persian Literature as World Literature. Literatures as World Literature. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-1501354205, ISBN 9781501354205

- ^ a b Nünlist, Tobias (2015). Dämonenglaube im Islam [Islamic Belief in Demons] (in German). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-110-33168-4.

- ^ Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, Healing Rituals and Spirits in the Muslim World. (2017). Vereinigtes Königreich: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. xxx

- ^ South Asian Folklore: An encyclopedia. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. 2020.

- ^ Reza Ebrahimil, Seyed; Bakhshayesh, Elnaz Valaei. Manifestation of Evil in Persian Mythology from the Perspective of the Zoroastrian Religion. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dīv". Encyclopædia Iranica. Dārā(b)–ebn al-Aṯir. Vol. VII, fasc. 4. 28 November 2011 [15 December 1995]. pp. 428–431. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Thomas Patrick (188). "Genii". Dictionary of Islam: Being a cyclopædia of the doctrines, rites, & ceremonies. London, UK: W.H. Allen. pp. 134–136.

- ^ a b Zarcone, Thierry; Hobart, Angela, eds. (15 March 2017). Shamanism and Islam: Sufism, healing rituals and spirits in the Muslim world. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781848856028.

- ^ Huart, Cl.; Massé, H. (2012) [1960-2007]. "Dīw". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_1879. Print edition: ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ MacNaghten, William Hay, ed. (1839). ʾAlf Laylah wa-Laylah [One Thousand and One Nights] (in Arabic). Vol. 1. Calcutta, IN: W. Thacker and Co. p. 20.

- ^ Herrenschmidt & Kellens 1993, p. 601.

- ^ Soudavar, Abolala (2015). The Original Iranian Creator God "Apam Napat" (or Apam Naphat?). Lulu.com. p. 14. ISBN 9781329489943.

- ^ "Daiva". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Hughes, Patrick; Hughes, Thomas Patrick (1995) [1885]. Dictionary of Islam: Being a Cyclopaedia of the Doctrines, Rites, Ceremonies, and Customs, Together with the Technical and Theological Terms of the Muhammadan Religion. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 134. ISBN 9788120606722. OCLC 35860600. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Demons and Illness from Antiquity to the Early-Modern Period. (2017). Niederlande: Brill.p. 115

- ^ Ronis, S. (2022). Demons in the Details: Demonic Discourse and Rabbinic Culture in Late Antique Babylonia. USA: University of California Press. p. 26

- ^ Experiencing the Beyond: Intercultural Approaches. (2017). Österreich: De Gruyter. p. 171

- ^ A Question of Identity: Social, Political, and Historical Aspects of Identity Dynamics in Jewish and Other Contexts. (2019). Österreich: De Gruyter.

- ^ Nasir, Mumtaz (1987). "'Baiṭhak': Exorcism in Peshawar (Pakistan)". Asian Folklore Studies. 46 (2): 159–178, esp. 169. doi:10.2307/1178582. JSTOR 1178582.

- ^ Yousefvand, Reza (2019). "Demonology & worship of dives in Iranian local legend". Iran Life Science Journal. Tehran, IR: Payam Noor University, Department of history.

- ^ Gertsman, Elina; Rosenwein, Barbara H. (2018). The Middle Ages in 50 Objects. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 9781107150386. OCLC 1030592502. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Ghan, Chris (May 2014). The Daevas in Zoroastrian Scripture (PDF) (M.A. / Religious Studies thesis). Columbia, MO: University of Missouri. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ^ Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, and Mehdi Aminrazavi, eds. An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Vol. 1: From Zoroaster to Omar Khayyam. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2007.

- ^ Sherman, Sharon R.; Koven, Mikel J., eds. (2007). Folklore/Cinema: Popular film as vernacular culture. University Press of Colorado / Utah State University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgnbm. ISBN 978-0-87421-675-2. JSTOR j.ctt4cgnbm.

- ^ Vol. VII, Fasc. 4, pp. 428-431

- ^ a b Shah, Portrayed in Shah Tahmasp'S. "Twin Spirits Angels and Devils Portrayed in Shah Tahmasp'S Shah Nameh Duncan Haldane." Paradise and Hell in Islam (2012): 39.

- ^ Iranian Studies: Volume 2: History of Persian Literature from the Beginning of the Islamic Period to the Present Day. (2016). Niederlande: Brill. p. 23

- ^ Volume XII, Harem I–Illuminationism, 2004.

- ^ a b c Melville, Charles, and Gabrielle van den Berg, eds. Shahnama Studies II: The Reception of Firdausi's Shahnama. Vol. 5. Brill, 2012.

- ^ ÇAKIN, Mehmet Burak. "SÜLEYMÂN-NÂME’DE MİTOLOJİK BİR UNSUR OLARAK DÎVLER." Turkish Studies-Language and Literature 14.3 (2019): 1137-1158.

- ^ Davaran, F. (2010). Continuity in Iranian Identity: Resilience of a cultural heritage. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. p. 207.

- ^ Çakin, Mehmet Burak (2019). "Süleymân-Nâme'de mİtolojİk bİr unsur olarak dîvler*" [Devs as a mythological element in the Solomon-Name epic]. Turkish Studies, Language and Literature. 14 (3). Skopje, [North] Macedonia / Ankara, Turkey: 1137–1158, esp. 1138. doi:10.29228/TurkishStudies.22895. ISSN 2667-5641. S2CID 213381726.

- ^ Vladimirovna, Moiseeva Anna (2020). "Prophet Sulaimān v klassische persische Poesie: Semantik und struktur des Bildes" [The prophet Solomon in classical Persian poetry: Semantics and structuring of images]. Orientalistik. Afrikanistik. (in German). No. 3. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Hamori, Andras (2015). On the Art of Medieval Arabic Literature. USA: Princeton University Press. p. 158.

- ^ Kușlu, Abdullah (2018). Die Korrelation zwischen dem Schöpfer und der Schöpfung in Masnavī von Rūmī [The Correlation between the Creator and the Creation in Masnavī by Rūmī] (in German).

- ^ Shalinsky, Audrey C. “Reason, Desire, and Sexuality: The Meaning of Gender in Northern Afghanistan.” Ethos, vol. 14, no. 4, 1986, pp. 323–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/640408. Accessed 9 Aug. 2023.

- ^ Tashjian, Virginia A., ed. (2007). The Flower of Paradise and Other Armenian Tales. Translated by Marshall, Bonnie C. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited. p. 27. ISBN 9781591583677. OCLC 231684930. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ a b Ananikian, Mardiros Harootioon (2010). Armenian Mythology: Stories of Armenian gods and goddesses, heroes and heroines, hells & heavens, folklore & fairy tales. Los Angeles, CA: Indo European Publishing. ISBN 9781604441727. OCLC 645483426.

- ^ Asatrian, G.S.; Arakelova, V. (2014). The Religion of the Peacock Angel: The Yezidis and their spirit world. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. p. 27.

- ^ Reza Yousefvand Demonology & worship of Dives in Iranian local legend Assistant Professor, Payam Noor University, Department of history, Tehran. Iran Life Science Journal 2019

- ^ Khosronejad, Pedram (2011). "The people of the air, healing, and spirit possession in [the] south of Iran". In Zarcone, T. (ed.). Shamanism and Healing Rituals in Contemporary Islam and Sufism. I.B. Tauris.

- ^ Diez, Ernst (1941). Glaube und welt des Islam [Belief and World of Islam] (in German). Stuttgart, DE: W. Spemann Verlag. p. 64. OCLC 1141736963. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Burton, Richard, ed. (2008) [1887]. Arabian Nights, in 16 Volumes. Vol. XIII: Supplemental Nights to the Book of a Thousand Nights and a Night. New York, NY: Cosimo Classics. p. 256. ISBN 9781605206035. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ^ Yarshater, Ehsan (series); Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Marzolp, Ulrich (eds.). A History of Persian Literature: Oral literature of Iranian languages – Kurdish, Pashto, Balochi, Ossetic, Persian, and Tajik. Vol. XVIII. New York, NY: Persian Heritage Foundation / Center for Iranian Studies, Columbia University. p. 225.

- ^ Turkish Mythology Dictionary - Multilingual: English – German – Turkish – Azerbaijani – Tatarian – Russian – Ukrainian – Arabic – Persian (Concepts and Meanings). (n.d.). (n.p.): Deniz Karakurt.

- ^ Karakurt, D. (2011). Türk söylence sözlüğü. Açıklamalı Ansiklopedik Mitoloji Sözlüğü, Ağustos.

- ^ Anikeeva, Tatiana A. "The Tale of the Epic Cycle of "Kitab-i Dedem Korkut" in Turkish Folklore of the 20th Century." Altaic and Chagatay Lectures: 43.

- ^ SHADKAM, Zubaida, and Selenay KOŞUMCU. "KİTÂB-I RÜSTEMNÂME-İ TÜRKÎ'DE DEV MOTİFLERİ ÜZERİNE BİR DEĞERLENDİRME." Milli Folklor 35.137 (2023).

- ^ a b Zhanar, Abdibek, et al. "The Problems of the Mythological Personages in the Ancient Turkic Literature." Asian Social Science 11.7 (2015): 341.

- ^ Doerfer, Gerhard; Hesche, Wolfram (1998). Türkische Folklore-Texte aus Chorasan [Turkish Folklore Texts from Chorosan] (in German). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 62. ISBN 978-3-447-04111-9.

- ^ Nureeva, G. I. ., Mingazova, L. I. ., Khabutdinova, M. ?ukhametsyanovna ., & Sayfulina, F. S. . (2022). The Personality of Children's Dramaturgy by Galimjan Gyilmanov. International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 9, 2353–2359. https://doi.org/10.6000/1929-4409.2020.09.284

- ^ Zadeh, Travis (2014). Commanding Demons and Jinn: The sorcerer in early Islamic thought. Wiesbaden, DE: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 142-149.

- ^ Orthmann, Eva; Kollatz, Anna (11 November 2019). The Ceremonial of Audience: Transcultural approaches. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 155. ISBN 978-3-847-00887-3.

Sources

[edit]- Herrenschmidt, Clarisse; Kellens, Jean (1993). "*Daiva". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 6. Costa Mesa: Mazda. pp. 599–602.