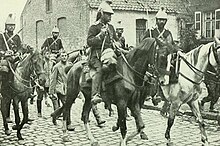

French cavalry during World War I

French cavalry during World War I played a relatively minor role in events. As mounted combatants proved highly vulnerable to the firepower of infantry and artillery, the various units of this arm essentially carried out auxiliary missions during the "Great War" (from 1914 to 1919), even if the beginning of the conflict corresponded to its peak in terms of mounted manpower.

Mainly deployed on the Western Front, the French cavalry took part in operations in the summer of 1914, mainly carrying out reconnaissance and patrol missions. Cavalrymen soon began to fight systematically dismounted,[1] firing their rifles. From autumn 1914 onwards, trench warfare led to a sharp decline in the role of cavalry: some regiments abandoned their horses, forming "dismounted cavalry divisions" and taking part in combat as infantrymen. The resumption of the maneuver warfare in 1918 restored the cavalry's usefulness as mounted infantry.

Several other cavalry regiments were sent to the other theaters of operations of the First World War, where they were sometimes much more useful on horseback than on foot: in the Maghreb, the Balkans, and the Middle East.

Finally, this period also saw the beginning of mechanization, with the French cavalry receiving a number of self-propelled machine guns for the first time.

Pre-war situation

[edit]The French army included several types of cavalry units, whose names, weapons, and uniforms were inherited. The cuirassiers and dragoons form the heavy cavalry, while the chasseurs à cheval and hussards belong to the light cavalry. Added to these are the chasseurs d'Afrique and spahis, the light cavalry of the African army. The differences between heavy and light cavalry concern the horses (Anglo-Normans on the one hand, and Anglo-Arabs or barbs on the other), the size of the riders (large in the heavy cavalry, small in the light cavalry),[note 1] and the service expected (the heavy cavalry is expected to face the opposing cavalry in pitched battles, while the light cavalry is responsible for small-scale warfare).

Between 1872 and 1913, a succession of laws altered the length of military service and the method of recruitment, which had an impact on the training of cavalrymen: in 1872, the length of service was set at five years and the drawing of lots was maintained;[2] in 1889, the length was reduced to three years;[3] Finally, the law of March 21, 1905, reduced the length of service to two years, while the drawing of lots was abolished.[4] This last law posed a problem for cavalry management, who felt they needed more time to train their riders. In 1913, the three-year law increased the length of military service by one year, which satisfied them.[5] Cavalry recruitment has traditionally been a little unusual: the proportion of cadres, i.e. officers and non-commissioned officers, is much higher than in the infantry;[note 2][6][7] a larger proportion of the workforce is made up of career soldiers;[note 3] and many descendants of the former nobility are to be found in the cavalry.[note 4][8]

Armament and uniforms

[edit]

All cavalrymen are armed with sabers, straight-bladed in the heavy cavalry and curved-bladed in the light cavalry.[note 5][9] The use of the spear in French cavalry had been abolished in 1871, but since 1890 this weapon has been distributed once again to all dragoon regiments, in response to the replacement of German uhlans' spears in 1889. Light cavalry also received the spear from 1913 onwards: a dozen hussar and chasseur regiments obtained it before going on the campaign.[10]

In heavy cavalry, the rider's head is protected by a metal helmet with a crest, while the nape of the neck is protected by a floating mane. Cuirassiers have the particularity of wearing a cuirass,[note 6][11] weighing eight kilograms, which provides effective protection from edged weapons, but not from shrapnel or bullets. From 1900 onwards, all heavy cavalry had to wear the dark blue cloth tunic (the cuirassiers' collar and facing tabs are madder, while those of the dragoons are white), madder pants (piped in dark blue), and the bluish iron-gray coat.[12]

For the light cavalry, the breeches were made of madder cloth, and the tunic of sky-blue cloth (the dolman with brandenburg was gradually replaced from 1900 onwards), intended to blend into the landscape background, as previous wars had demonstrated the benefits of a little camouflage. Experiments were carried out to find an even less conspicuous field outfit: the "reseda" color (a dark green) was tried out in 1911 by the 12th chasseurs garrisoned at Saint-Mihiel. The difference between regimental types was limited to the collar and facing tabs, madder for the chasseurs, and sky-blue for the hussars. To replace the shako, a dozen helmets were tested between 1879 and 1913 in several hussar and chasseur regiments: initially of the "policeman" type, or with crest, in leather (sufficient to protect against saber blows), then in metal (steel and copper or aluminum). The helmet adopted in 1913 resembled that of the dragoons, with a steel bombshell adorned with a brass band (with a decoration on the front representing a hunting horn for the chasseurs or a five-pointed star for the hussars), the crest bearing a mane, and a canvas field helmet cover: only a few regiments were partially equipped in 1914, with deliveries scheduled until 1919.[13]

Organization

[edit]

The cavalry is structured in hierarchical units, with each level having a theoretical strength. Around 30 cavalrymen form a platoon commanded by a lieutenant or second lieutenant; four platoons make up a squadron of 120 to 135 horses under the command of a captain; four squadrons are grouped in peacetime into a regiment of around 500 sabers,[note 7] commanded by a colonel or lieutenant-colonel (two squadrons, or a "half-regiment", may be entrusted to a squadron leader).

In October 1870, the Imperial Guard was disbanded and its six cavalry regiments were renamed.[note 8] The lancer regiments all disappeared in 1871.[note 9][14] After the French defeat of 1871 and the dissolution of the marching regiments, the French cavalry numbered 56 regiments in mainland France and seven in North Africa, including 12 cuirassiers, 20 dragoons, 10 hussars, 14 chasseurs, four chasseurs d'Afrique and three spahis. Added to these is the Republican Guard cavalry regiment, part of the Gendarmerie. The strength of all French troops was increased to bring them up to the level of their German neighbors, in a kind of arms race that continued until 1914. In 1873, 14 new cavalry regiments were created.[15] The 1875 loi des cadres et effectifs thus provided for 70 regiments in metropolitan France (12 cuirassiers, 26 dragoons, 12 hussars and 20 chasseurs) and seven regiments in North Africa (four chasseurs d'Afrique and three spahis).[16][17] Some of these regiments were grouped to form five cavalry divisions, each with three brigades (cuirassiers, dragoons, or light cavalry); the remainder were assigned to each army corps, each with one cavalry brigade (one light cavalry regiment and one dragoon regiment).[17]

Further increases followed, notably in 1887, to boost the number of active officers and non-commissioned officers. In 1913, due to the increase in the number of large infantry units (in response to the German army's rising strength), four new cavalry regiments were created,[18][17] bringing the total to 89: 12 cuirassiers, 32 dragoons, 21 chasseurs, 14 hussars, 6 chasseurs d'Afrique and 4 spahis.[note 10] In metropolitan France and peacetime, all cavalry regiments were now envisioned; the network of barracks (known as a "quartier" in the cavalry) covered the entire country, with a greater concentration in the East (along the border with Germany) and around Paris (for the maintenance of order). There are also remount depots, responsible for purchasing, breeding, and preparing horses, located mainly in the West.

Doctrine of Employment

[edit]

Following the experience of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870,[19] characterized by the failures of large cavalry charges during the battles of Frœschwiller and Rezonville, the cavalry maneuver regulations of 1876 and 1882 leaned towards a defensive use of cavalry (avoiding frontal charges, with priority given to reconnaissance and patrols). Later, a more offensive approach—seeking confrontation with enemy cavalry—became favored. Several roles were assigned to the cavalry:

The cavalry informs the command, covers the deployment of other arms, and protects them against combat surprises. It constantly seeks opportunities to intervene effectively in action and cooperates with infantry attacks. It exploits success through relentless pursuit; in retreat, it sacrifices itself entirely if necessary, to give other troops time to withdraw from combat. The mounted attack with cold steel, which alone yields rapid and decisive results, is the cavalry's primary mode of action. Dismounted combat is employed when the situation or terrain temporarily prevents cavalry from achieving its assigned goal through mounted combat.

— Service of the Armies in the Field, decree of December 2, 1913, Article 99[20]

All cavalry units were trained to fight on foot as well, recognizing the vulnerability of cavalry to gunfire—a mounted soldier presented an easy target, standing 2.5 meters tall. In such cases, horses were left behind under guard, while the soldiers formed skirmish lines (referred to as "foragers" in cavalry terms), taking cover wherever possible and firing with their carbines. Each cavalry brigade also included a machine gun section (often attached to one of the regiments, equipped with two Saint-Étienne model guns).[note 11] Cavalry divisions had additional resources, such as cyclists (who also fought on foot) and artillerymen, providing some measure of firepower.

The Regulations on Cavalry Maneuvers, by affirming that dismounted combat will be required more frequently in the future than in the past to maximize the weapon's offensive potential, has placed significant emphasis on marksmanship training.

— Regulations on Cavalry Shooting Instruction, 1913[21]

Traditional cavalry missions included reconnaissance, ambushes, and the protection of marching columns and camps. In 1881, General de Galliffet wrote: "In modern warfare especially, cavalry combat is an incidental event, whereas reconnaissance and security are constant necessities. Although a cavalry division must always form a striking force capable of attacking the enemy, it will very rarely find opportunities for direct engagements."[22]

|

Mobilization Planning

[edit]

According to Plan XVII of 1914, each of the army's major units was to receive a contingent of cavalry. The 21 army corps were each assigned six squadrons, usually from the same light cavalry regiment. Of these, the first four squadrons remained grouped, while the 5th and 6th were attached to the two infantry divisions within the corps,[23] with one platoon assigned to every infantry regiment to serve as scouts. Additionally, the 25 new "reserve divisions" created during mobilization were to each receive a squadron, mainly composed of reservists. Finally, the 12 new "territorial infantry divisions"[24] were allocated part of the 37 "territorial cavalry squadrons," which were also tasked with guarding communication routes and fortresses. These squadrons were provided by the military regions at a rate of two per region (except for the 19th and 21st regions, and only one squadron for the 6th and 20th regions). The first squadron consisted of light cavalry, the second of dragoons, both numbered consecutively after the other squadrons in each regiment, leading to regiments containing up to a 10th or 12th squadron.

The regiments not assigned to these units (mostly dragoons and cuirassiers) were grouped into ten cavalry divisions (CDs), each with three brigades (except for the 10th Division, which had only two).[23] All these cavalry divisions included a mounted artillery group composed of three batteries, each equipped with four 75 mm guns (the artillerymen rode on horseback and did not travel on caissons and limbers as was typical for other field artillery units).[note 12][25]

Thus, according to the Service of the Armies in the Field regulations of 1913, two types of cavalry units were planned for wartime: "army cavalry" (58 regiments grouped within cavalry divisions) and "corps cavalry" (21 regiments dispersed across the various army corps). According to the intelligence plan of Plan XVII,[26] the army's commander-in-chief could rely on information from army cavalry reconnaissance missions, aerial exploration (the military aeronautics division in 1914 included 26 squadrons and about a dozen dirigibles),[27] and agents from special services (the Second Bureau and the Service de Renseignements).

Western Front

[edit]

The Year 1914

[edit]The early stages of the war on the Western Front were marked by a war of movement from August to November 1914, during which the cavalry was theoretically able to fulfill its role. At the operational level, it provided intelligence to the command and acted as a flank guard, while at the tactical level, it remained more mobile than the infantry.[citation needed]

Mobilization Coverage

[edit]-

A charge of German hussars during the Kaisermanöver ("Imperial Maneuvers") of 1912: The German Emperor appreciated the massive cavalry charges, which impressed the military attachés. The German army had eleven cavalry divisions, but they were spread over two fronts.

-

Drawing by Georges Scott on the front page of L'Illustration of August 29, 1914: "On the road to Berlin." The Russian army lines up 36 cavalry divisions, including 10 facing East Prussia and 18 facing Galicia.

During the war of 1870, cavalry played an important role, particularly on the German side [...]. In Germany, a true doctrine emerged: the next war would see the triumph of German cavalry [...]. Faced with this specific threat, France actively prepared its cavalry to repel, through offensive maneuvers, the assaults of the innumerable squadrons the enemy dreamed of unleashing upon its territory.

— Liliane and Fred Funcken, L'uniforme et les armes des soldats de la Guerre 1914-1918[28]

As a result, the first role assigned to the French cavalry by successive mobilization plans was to deploy along the Franco-German border as soon as the first days of mobilization began. Most of its regiments were pre-positioned nearby to ensure the smooth execution of French troop mobilization and concentration operations (a sudden attack was feared). This was referred to by the general staff as "coverage."

The deployment of active units from the five army corps along the border (the 2nd, 6th, 20th, 21st, and 7th corps) began on the morning of July 31, 1914, as part of a "full mobilization exercise," though positioned ten kilometers behind the border (by government order).[29] The recall of reservists from these corps was ordered on the evening of August 1, and the first troop trains transporting units from their barracks to their deployment zones were reserved for the "coverage divisions." Consequently, half of the French cavalry was deployed just before the mobilization was officially declared to form a protective screen, with each squadron accompanied by an infantry battalion:[30]

- The 8th Cavalry Division (in the 7th Corps sector) was deployed in the High Vosges region (from Belfort to Gérardmer).

- The 6th Cavalry Division (21st Corps) covered the Haute-Meurthe area (from Fraize to Avricourt).

- The 2nd Cavalry Division (20th Corps) was deployed in the Basse-Meurthe area (from Avricourt to Dieulouard).

- The 7th Cavalry Division (6th Corps) covered Southern Woëvre (from Pont-à-Mousson to Conflans).

- The 4th Cavalry Division (2nd Corps) was deployed in Northern Woëvre (from Conflans to Givet).

Rapid Deployment

[edit]

At the same time, the 1st Division, composed of regiments stationed in Paris, Versailles, and Vincennes, boards trains on August 1 (the two Parisian cuirassier regiments were scheduled to leave on July 31 but were held back by government order for an additional day due to fears of protests). They disembark on August 2 at stations around Mézières.[31] This division is joined by an army corps staff led by General Sordet, as well as the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Divisions. Together, they form the "Cavalry Corps" on August 2, which deploys as a cover in the Ardennes department, protecting the left flank of the French forces and standing ready to conduct reconnaissance in Belgium if necessary.[32] In Paris, the Republican Guard remains in the city to maintain order and perform military police duties (tracking draft dodgers and deserters). Its cavalry regiment replaces the Parisian cuirassiers (who have gone to the front) in carrying out mounted presidential escorts.[33]

The last two cavalry divisions arrive from further afield: the 10th CD (stationed in Limoges, Libourne, Montauban, and Castres) and the 9th CD (stationed in Tours, Angers, Luçon, Nantes, and Rennes).[34] They complete their ranks starting on the first day of mobilization and board trains (one convoy per squadron, four for an entire regiment) to disembark in eastern France by August 5, the fourth day of mobilization. Upon arriving, the cavalrymen immediately advance to cover subsequent deployments,[35] which continue for two weeks until August 18. As for the cavalry units assigned to larger infantry formations, they arrive alongside them, the last being squadrons integrated into divisions from the Army of Africa (the 37th ID from Philippeville, the 38th from Algiers, the 45th from Oran, and the Moroccan Division).

Battle of the Frontiers

[edit]The initial engagements are skirmishes between patrols, tasked with probing enemy dispositions and gathering intelligence by interrogating civilians and capturing prisoners to identify opposing units. The first units involved are those garrisoned near the border. For example, in Belfort, the 11th and 18th Dragoon Regiments (part of one brigade of the 8th CD) are sent to monitor the border on July 31, 1914, at 5:00 AM, with alert cantonments in Morvillars and Grandvillars. On August 1, the 11th Dragoons canton in Joncherey with a battalion of the 44th Infantry Regiment under their command. On August 2, at 10:00 AM, "a German patrol from the 5th Chasseurs, composed of one officer and eight cavalrymen, arrives at Joncherey. It is fired upon by an infantry section holding the Tuileries on the road to Faverois; the officer is killed (Lt. Mayer). At 10:15 AM, the 3rd squadron mounts up and is sent on reconnaissance" (11th Dragoons' war diary).[36]

Operations began on August 7, 1914, when French troops entered Upper Alsace. As expected, the cavalry leads the way, with the 1st Squadron of the 11th Dragoons spearheading the 8th CD column, crossing the Franco-German border at Seppois-le-Bas at 6:00 AM. At 11:15 AM, a patrol from the same regiment comes under fire in Altkirch, followed by German artillery striking the entire brigade as it assembles on a plateau. After the infantry enters Mulhouse, the Dragoon brigade is tasked with monitoring the Sundgau and the road to Basel,[note 13] with cantonment on August 8 at Tagsdorf, with the 11th regiment moving to Jettingen on August 9 and the 18th Dragoon Regiment extending reconnaissance as far as Uffheim. It is advised in this area, increasingly close to the Rhine, to avoid nighttime exposure to searchlights from Istein.[36] A general retreat to the safety of the Belfort fortress is ordered on August 10 following the French defeat near Mulhouse.

On the Lorraine plateau, the cavalry is similarly limited to reconnaissance and maintaining a thin patrol line, leaving the infantry to hold resistance lines. For example, Lunéville serves as the primary garrison for the 2nd Cavalry Division, which has four regiments stationed there: the 8th and 31st Dragoons and the 17th and 18th Chasseurs. The first skirmish between cavalry patrols occurs on August 4, with the division's baptism of fire on August 6 during an artillery duel following a supply requisition in Vic (then German).[note 14][37] These regiments are not engaged in battles around Cirey on August 10, La Garde on August 11th,[note 15][38] Badonviller on August 12, or the major confrontations at Morhange and Dieuze (Battle of Morhange) on August 20, which are fought by infantry.

During the offensive, half of the cavalry divisions are grouped into two provisional cavalry corps (without organic units). On the Lorraine plateau, the 2nd, 6th, and 10th CD form the Conneau Corps starting August 14, 1914,[39] tasked with connecting the 1st and 2nd Armies separated by the lake region. For the offensive in the Belgian Ardennes, the 4th and 9th CD were combined into General Pierre Abonneau's corps as of August 18, 1914, attached to the 4th Army. However, the French defeat leads to the corps' dissolution by August 25.[40]

Everywhere, the cavalry fails to provide adequate intelligence on enemy positions. In Lorraine, they lose contact with the Germans just before their counterattack at the Battles of Morhange and Sarrebourg on the morning of August 20. The same happens in the Belgian Ardennes, where French columns are decimated during the Battle of the Ardennes on August 22 by two unidentified German armies. As a result, several commanding officers are dismissed for their perceived responsibility: Generals Lescot (2nd CD) on August 13, Aubier (8th CD) on August 16th for "absolute inertia,"[41] Gillain (7th CD) on August 25, and Levillain (6th CD) on August 27.

The Sordet Corps in Belgium

[edit]When the Belgian government authorized the French to enter Belgium on the evening of August 4, 1914,[42] orders were given to conduct reconnaissance missions on August 5,[43] followed by advancing the entire corps north of Neufchâteau to scout towards Martelange and Bastogne.[44] By August 7, the cavalry units reached the Lesse River,[45] and on August 8, Sordet reported that the area "was free of Germans" up to Liège.[46] On August 9, the Belgians requested French cavalry north of the Meuse to protect Brussels, as at least one German cavalry division was marching from Tongeren toward Sint-Truiden.[47]

However, on August 11, the cavalry corps reported the arrival of significant German forces from the east:[48] the German 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Armies, a force of 743,000 men, including five cavalry divisions, had begun their advance. To avoid combat, the cavalry corps retreated, crossing to the left bank of the Meuse on August 15 and coming under the command of the French 5th Army. It held its position north of the Sambre River, occasionally pushing as far as Gembloux. On August 20, the commander-in-chief, through the 5th Army commander, sent Sordet a letter criticizing his handling of operations and proposing his replacement.[49]

Following the French defeat at Charleroi and the British defeat at Mons, the cavalry corps joined the Great Retreat from August 22 to September 6, passing through Maubeuge, Péronne, Montdidier, Beauvais, Mantes, and Versailles, unable to slow the German pursuit. For example, they failed to hold the bridges over the Somme near Péronne on August 28. These long marches and counter-marches, resembling a carousel, exhausted the horses under the sweltering heat:

We are beginning to feel the effects of the lack of sleep and the heat [...] The horses, too, have been saddled for twenty-four hours straight with heavy loads. They are no longer spirited! The poor beasts heads low and legs spread, remain where they are left, in a complete stupor!

The Battle of the Marne

[edit]

During the Great Retreat, the Sordet Cavalry Corps (1st, 3rd, and 5th Cavalry Divisions), the French 5th Army, and the British Army crossed northern France, pursued by German forces. The cavalry corps was no longer combat-ready: soldiers whose mounts had died from exhaustion traveled on foot,[51] while a "provisional cavalry division" was created on August 29 (under General Cornulier-Lucinière, dissolved on September 8)[52] using the remaining operational units. This division was assigned to the newly formed 6th Army.[note 16][53]

By the early days of September 1914, the Sordet Corps had taken refuge southwest of Paris, while the Conneau Corps (4th, 8th, and 10th Cavalry Divisions) maintained the connection between the British forces and the French 5th Army. Meanwhile, the 9th Cavalry Division linked the French 9th and 4th Armies. Their mission was to ensure the continuity of the front between the different armies.

However, on August 31, Captain Charles Lepic (of the 5th Chasseurs, 5th Cavalry Division) reported from Gournay-sur-Aronde (north of Compiègne) that a German column had abandoned the road to Paris and was heading southeast.[note 17] This intelligence was confirmed in the following days by other patrols (Captain Fagalde recovered a German staff map) and by aerial reconnaissance from the Paris fortified zone.

The Battle of the Marne consisted of several engagements, during which cavalry was primarily tasked with covering operations, though it sometimes played a more active role. For example, the three divisions of Bridoux's Corps, particularly the 5th Cavalry Division, participated in the Battle of the Ourcq. The Conneau Corps took part in the Battle of the Two Morins, while the L'Espée Corps (formed on September 10 with the 6th and 9th Cavalry Divisions, attached to the 9th Army, and dissolved on September 13)[40] fought in the Battle of the Marshes of Saint-Gond near Mailly-le-Camp.

Pursuit and Race to the Sea

[edit]

After the battles on the Marne, cavalry units were logically sent ahead for the pursuit, but their progress was extremely slow as the horses were utterly exhausted, barely managing to round up a few stragglers. The cavalry "arrived exhausted at the Battle of the Marne, and there, [...] when this [...] victory could have [...] become an irreparable rout for the Germans, there were no horses fit to march."[54] As early as September 8, what remained of the 5th Cavalry Division[note 18][55] was sent on a raid through Crépy-en-Valois behind German lines, into the forests of Compiègne and Villers-Cotterêts.[56] During this raid, a squadron of the 16th Dragoons (commanded by Lieutenant de Gironde) succeeded in attacking an automobile convoy transporting aircraft on the evening of September 11 near the Mortefontaine Plateau. Initially, two platoons dismounted to skirmish, followed by a mounted platoon charge, which was cut down by machine-gun fire.[57][note 19][58]

On September 9, an attack on the Rozières Plateau gave the 1st Cavalry Division and the 13th Dragoon Brigade of the 3rd Cavalry Division, under General Bridoux, the opportunity to charge and repel several enemy infantry battalions.[59] On September 10, two cavalrymen from the 3rd Hussars (3rd Cavalry Division) captured the flag of a Saxon regiment after attacking a group of about fifteen isolated Germans in Mont-l'Évêque.[note 20][60]

The pursuit was halted on September 14 as the French cavalry was incapable of effectively engaging German infantry, though additional raids were carried out. For instance, on September 14–15, the 10th Cavalry Division infiltrated between the German 1st and 2nd Armies, crossed the Aisne at Pontavert, and reached the Sissonne camp before retreating.[61]

During the Race to the Sea, cavalry units were used as mounted infantry, tasked with temporarily holding positions until infantry battalions arrived. Nine of the ten cavalry divisions were deployed on the left flank, with only the 2nd Cavalry Division remaining in Woëvre. On September 15, a new "provisional cavalry division" was created under General Beaudemoulin with remaining available forces, such as the Gillet Brigade and reserve squadron groups. It was engaged near Péronne on September 25 but dissolved on October 9.[52] However, cavalry units were small in number, lacked machine guns, had no tools to dig defensive positions, and carried too little ammunition. In one instance, dismounted cavalry charged enemy infantry with lances (lacking bayonets). On October 20, 1914, near Stadenberg, close to Ypres, two squadrons of the 16th and 22nd Dragoons carried out such a charge.[62]

On September 30, two cavalry corps were organized on the left flank and engaged near Arras: the 1st Corps (1st, 3rd, and 10th Cavalry Divisions) under General Louis Conneau and the 2nd Corps (4th, 5th, and 6th Cavalry Divisions) under General Antoine de Mitry. On October 5, 1914, a "cavalry corps grouping" was established in the Lens region with these two corps, under General Conneau and attached to the 10th Army, in an attempt to outflank the German right wing. Engaged immediately in the Battle of Artois (at Aix-Noulette and Notre-Dame-de-Lorette), this grouping was disbanded by October 7 after its failure. It was re-established on October 12 in Flanders (after being moved by rail) on the banks of the Lys but was permanently dissolved on October 16.[63]

Once the front stabilized, reconnaissance missions were exclusively assigned to aviation, while the capture of prisoners (to gather intelligence) was left to shock troops during raids. Tens of thousands of horses perished, mainly from exhaustion due to the pace of operations, lack of care, and insufficient forage.[64]

Trench Warfare (1915-1918)

[edit]

Awaiting a Breakthrough

[edit]A third cavalry corps was established for this purpose on September 2, 1915 (comprising the 6th, 8th, and 9th Cavalry Divisions) under General de Buyer's command, only to be dissolved on December 28, 1916.[65]

For example, in autumn 1915, seven cavalry divisions awaited the success of the Second Battle of Champagne: the 3rd Cavalry Corps (6th, 8th, and 9th Cavalry Divisions) was assigned to the 2nd Army; the 2nd Cavalry Division and the 2nd Cavalry Corps (4th, 5th, and 7th Cavalry Divisions) supported the 4th Army; while the 1st and 3rd Cavalry Divisions, along with the Spahi Brigade, were placed within the 10th Army for the Third Battle of Artois.[66]

Orders dictated that they remain "ready, as soon as the breach appears sufficiently wide, to promptly send one or several divisions through it, which must then sweep east and west to strike the rear of the enemy's second line."[67] On September 28, breaches were reported in German lines: the 8th Cavalry Division advanced south of Perthes-lès-Hurlus, and the 5th Cavalry Division moved north of Souain.[68] However, the resilience of the German front prevented any exploitation.

Thus, there are currently thousands of cavalrymen behind our front: men caring for the horses, men transporting the vast amount of fodder required for said horses. These men play a role in the war almost equivalent to the one they would play if they were in Timbuktu.

— H.G. Wells, after visiting the front.[69]

|

Charging Between the Trenches

[edit]In this attack, the headquarters staff and the three leading squadrons, particularly the 5th, suffered the most severe losses in men and horses. The rear squadrons (2nd, 4th, and 7th) fared better. Wounded chasseurs were treated and evacuated with great difficulty. Many wounded horses roamed or lay in the trenches, where they were put down.[70]

The severely reduced dismounted detachment continued ensuring passage through German trenches for the infantry until the following morning. From September 26 to 29, the cavalry regiment remained at the front, clearing German shelters captured by the infantry, awaiting a favorable moment for another charge. On September 29, the Army Corps abandoned the idea of using mounted cavalry and withdrew the remnants of the regiment from the front.[70]

Other Occupations

[edit]Unable to fight on horseback, cavalry units were primarily tasked with traffic control and policing within the army zones, supporting the gendarmerie provosts due to the lack of more specialized roles. To address this inactivity, cavalry regiments were regularly sent into the front-line trenches to perform infantry duties, leaving their horses far to the rear. For example, dismounted cavalrymen of the 10th CD held the sector between Leimbach and Burnhaupt-le-Haut for most of 1915, alongside some territorial infantry.[71] During the Champagne offensive in the autumn of 1915, the foot groups and artillery of the 2nd Cavalry Corps were engaged in support of the 6th Army Corps, suffering an estimated total of 1,399 casualties (201 killed, 714 wounded, and 484 missing).[72]

In 1917, during the period of mutinies and strikes, cavalry units were relatively spared from the unrest due to their structure and recruitment methods. However, the cavalrymen of the 25th Dragoons were among the first to sing The Internationale on May 28, 1917, at their quarters in Vendeuil (south of Saint-Quentin).[73] To maintain order, the dragoon brigades of the 1st Cavalry Corps were sent at the end of May to deal with the mutinied units[74] and were later rotated through major industrial centers, participating in police operations, with detachments stationed at train stations and depots to monitor the return of soldiers on leave.[75]

Additionally, cavalry units provided labor detachments to enhance the front's defenses (digging trenches, constructing fascines, etc.), assist with farming work (as noted in a service memo from a brigade of the 10th CD that "authorized unit commanders to lend men and horses to local inhabitants to assist with their work"),[76] conduct earthworks in fortified regions (e.g., the 11th Hussars at Fort La Chaume in Verdun), and, in one instance, prepare an airfield (the 22nd Chasseurs in 1915).[76]

Creation of Mounted Units

[edit]At the end of August 1914, the military governor of Paris scraped together resources to form units: a temporary cavalry brigade consisting of two regiments was assembled from reservists present in depots in the Paris region, commanded by a few officers from the Saumur application school. On August 25, the "Mixed Cavalry Regiment" was formed, composed of reserve squadrons from the 15th Dragoons and 8th Hussars; it became the "Mixed Marching Cavalry Regiment," which was finally dissolved on December 31, 1916.[77] On August 26, 1914, the 33rd Dragoon Regiment was created from the 7th squadrons of the 6th, 23rd, 27th, and 32nd Dragoon Regiments (whose depots were in Vincennes and Versailles); it was dissolved on January 20, 1916.

On October 9, 1914, another temporary cavalry brigade was formed on the banks of the Meurthe from divisional squadrons (6th and 10th Hussars). The "Reserve B Hussar Regiment" lasted long enough to be renamed the 17th Marching Hussar Regiment on August 19, 1915, but it too was dissolved on January 7, 1916.[78]

In December 1914, the Matuzinski Brigade was organized to complete the 10th CD and renamed the 23rd Light Brigade in April 1915. The "Marching Regiment of the 12th Hussars" was created on December 12, composed of the reserve squadron group from the 12th Hussars (5th and 6th, from the 71st DI) and the 11th squadron (previously assigned to the Belfort area). The 3rd Chasseur Regiment depot provided a dismounted squadron on June 29, 1915. The regiment was renamed the 16th Marching Hussar Regiment on July 30, 1916, and was dissolved on January 7, 1916.[79] The "Marching Regiment of Mounted Chasseurs" was created on December 14, 1914, using the 6th Squadron of the 11th Chasseurs, the 5th of the 14th Chasseurs, and the 11th of the 16th Chasseurs.[80] It became the 22nd Mounted Chasseur Regiment in 1915 and was dissolved on January 4, 1916.

Dismounting

[edit]Starting in October 1914, each cavalry division was required to form a "light group," equivalent in size to an infantry regiment with three battalions. This group consisted of one dismounted squadron from each of the division's six regiments. By June 1916, most of these ten light groups were incorporated into the foot cuirassier regiments.[81]

On June 1, 1916, the "1st Light Regiment" was created, a three-battalion infantry regiment (65 officers and 2,474 men) with three machine gun companies (three officers and 123 men). It was formed from the "light groups" of the 2nd and 10th Cavalry Divisions, a reserve squadron from the 29th Dragoons, and some elements taken from mounted regiments. All officers came from the cavalry; each battalion comprised two squadrons. The commander was a cavalry colonel who had previously led the 373rd Infantry Regiment. Assigned to the 2nd Cavalry Division, the regiment took its position on the front line near Seppois-le-Haut during the night of June 1–2. The regiment, the only one of its kind, was disbanded on August 15, 1917, to be replaced by a foot cuirassier regiment.[82][83][84]

In May 1916, six cuirassier regiments were dismounted (their horses reassigned to artillery): the 4th, 5th, 8th, 9th, 11th, and 12th became "foot cuirassier regiments." Initially assigned to individual cavalry divisions, these regiments were later grouped into two "foot cavalry divisions" between December 1917 and January 1918. These regiments were deployed in offensives, such as the 4th, 9th, and 11th Cuirassiers' involvement in the capture of the Laffaux Mill in April 1917 during the Battle of the Chemin des Dames.

On November 11, 1915, 48 squadrons were removed from infantry divisions and dissolved. By December 31, 1915, 29 dragoon squadrons were disbanded and replaced by light groups (on foot).[85] On June 1, 1916, the 9th and 10th Cavalry Divisions were disbanded, followed by the 8th Division on August 5, 1916, and the 7th Division in July 1917. Many officers and cavalrymen were transferred to infantry, artillery, and aviation. As their role diminished, the cavalry's total strength decreased slightly during the conflict, from 3.7% of the army in 1914 (102,000 men) to 3.2% (91,000) in 1918.[86] Meanwhile, the technical branches (artillery, engineering, logistics, medical, aviation, and assault artillery) expanded. During the war, 4,800 cavalry officers switched to other branches, notably aviation and tanks. By 1915, half of the non-commissioned officers in cavalry regiments had transferred to the infantry to become section leaders.[87]

Uniforms and Equipment

[edit]At the beginning of the campaign, cuirassiers wore breastplate covers, while all cavalrymen had fabric helmet covers to prevent sunlight reflections on metal parts, which were visible from afar. On October 16, 1915, the production of blue canvas breeches was ordered to cover or replace the madder red [88] breeches of the light cavalry.[89] Similarly, from March 27, 1915, horses with light-colored coats were to be dyed using paraphenylenediamine or potassium permanganate.[note 21] The adoption of Horizon blue uniforms began in December 1914 and was completed by the end of 1915. From that point on, all cavalrymen wore the same uniform as the infantry, except for minor details.[90] Adrian helmets were distributed starting in June 1915 when shakos and crested helmets were in short supply, and their use became mandatory from October 16, 1915, for all cavalry units on the front, including the Chasseurs d'Afrique. Gas masks were also distributed, including for horses.

The supply of tools was expanded: in addition to billhooks, saws, and axes (necessary for bivouacs), units received entrenching tools and wire cutters (94 and 20 per squadron, respectively) as well as division-level supplies stored in three trucks (260 shovels, 130 picks, 30 axes, sandbags, barbed wire, etc.).[91]

The carbine was replaced by the Berthier Model 1892 carbine (featuring a bayonet mount) in October 1914. Surviving carbines were converted into carbines in 1915. These carbines were further modified starting in 1916 (and into the 1920s) to hold five-round magazines instead of three. Lances were abandoned, and breastplates were sent to depots in September 1915. Firepower was increased: starting in April 1915, each regiment was required to include a machine gun section. Ammunition allocations rose from 96 cartridges per cavalryman to 165 (75 in the cavalryman's pouches and 90 in the horse's cartridge collar).[91] Units underwent training in infantry tactics and grenade throwing.

From March 1, 1916, some light machine guns (Chauchat Model 1915 with 20-round magazines) were issued, with four per squadron.[92] Regiments received 36 grenade launchers with 1,000 VB rifle grenades, grenade pouches or belts (150 incendiary grenades per regiment),[91] and small 37mm cannons (Model 1916).

After prewar experimentation, the first motorized armored vehicles were deployed in combat. These were modified civilian vehicles based on the chassis of small trucks or large cars (from manufacturers such as Renault, Peugeot, Delaunay-Belleville, De Dion-Bouton, or White Motor Company). They were fitted with light armor and armed with a machine gun or a small semi-automatic cannon (37mm or 47mm)[93] from naval stockpiles.[94] While the initial crews were sailors, they were soon replaced by cavalrymen.[95] Groups of these armored cars and cannons (GAMAC) were incorporated into units, with one group per cavalry division. The 8th Cavalry Division received its group in October 1914, followed by the 9th in November and the 7th in December. The remaining divisions were equipped in 1915. By November 1915, the 7th Division had two groups, with other divisions following in May–June 1916. Among the 17 groups created, the 10th was notable for being deployed to Romania starting in August 1916.[81]

Evolution of Doctrine

[edit]The characteristic of the battlefield is the absolute emptiness it presents. Airplanes report that they cannot spot gatherings or large columns anywhere. Cavalry must not remain the only force that continues to present and move visible targets within the action zone. Therefore, it is necessary to particularly modify its methods of marching, stationing, and combat.

— Ernest Adrien de Sézille (captain), Practical Advice for Cavalry Commanders (War of 1914): Summary of New Methods Imposed by the Current War, Based on the Experience of Many Months of Campaigning, December 1915.[96]

From this point onward, mounted units near the front were required to remain in open formations, with riders spread out and staggered across the terrain. New documents formalized the theoretical use of cavalry, such as the Instruction on the Use of Cavalry in Battle dated December 8, 1916, and revised on May 26, 1918 (signed by General Pétain),[97] which governed the engagement of units. It was decided that, when dismounted riders were used as infantry on a stabilized front, the cavalry units applied the infantry regulations.[98] The document defined the new properties of cavalry:

1° Speed and mobility are the distinguishing qualities of cavalry; the missions assigned to it in battle derive from these properties, which other forces do not possess to the same degree.

2° Cavalry tactics must take into account the power of modern firepower; its current organization and armament allow it to exploit this. Cavalry must therefore be capable of fighting on foot, in coordination with its artillery. Nevertheless, mounted combat must be anticipated and prepared for—it is necessary against cavalry that accepts or seeks it, against infantry caught off guard in open terrain, disorganized, demoralized, exhausted, or out of ammunition, against wheeled artillery, or artillery positions taken from the flank or rear.

3° Cavalry is a fragile force; its reconstitution is long and difficult. It must not be sacrificed out of impatience to find a role, in conditions where its special qualities cannot be utilized.

— Instruction on the Use of Cavalry in Battle 1918, Volume 1, p. 9-10.[97]

Its role in combat, during an offensive, is "to ensure the development of success [...] and, as success expands, to enable further exploitation." On the defensive, "cavalry will be able to limit the effects of a sudden rupture in the defensive battlefield's organization." Finally, "in the event of an enemy retreat, it will scout and cover the army's advance."[99]

At the tactical level, cavalry was now to be used as mounted infantry, fighting primarily on foot and using its mobility to move to the flanks or rear of the enemy, combining firepower and movement.[100] At the divisional level, it was considered assigning light tank sections or companies to cavalry divisions.

This text was drafted during preparations for General Nivelle's offensive in April 1917.[101] The command hoped to deploy cavalry through a breach in the front, finally breaking into open terrain.

Resumption of Mobile Warfare (1918)

[edit]The Allied offensives that began in the summer of 1918 consisted of successive blows against the German frontlines, each stopping at the limit of artillery range, with no attempt to break through.[102] Progress was therefore slow, and cavalry was only engaged in dismounted combat:

Ah! Certainly, this is no longer a pursuit like those of the past, one of those high-speed chases that were essentially the work of cavalry accompanied by horse-drawn batteries: dragoons and hussars scattering columns of fugitives, cutting off roads, slashing at teams of horses. No more feats like those of Lasalle and his peers after Jena, the annihilation of Prussian armies down to their last remnants, and fortresses surrendering to a handful of cavalrymen. Now, the pursuit is carried out step by step. It is infantry chasing infantry. The withdrawing side shields itself with networks of machine guns and light cannons, entrenched in every slight rise in the ground. The advancing side moves forward only with caution, absorbed as it is in clearing terrain littered with traps.

— General Fonville, October 24, 1918.[103]

As of November 1, 1918, the Allies had six French cavalry divisions on the French front, supported by three British and one Belgian division (a small number compared to the 209 Allied infantry divisions on this front).[104] Cavalry forces consisted of 66,881 French, 18,894 British, 6,971 Belgian, and 6,028 American troops, with an additional 633 French cavalrymen on the Italian front.[105]

Each of the two corps was reinforced with one, then two squadrons, a company of balloonists, four artillery groups (three with 75 mm guns and one with 105 mm guns), three engineering companies, and one, then two, groups of armored cars and autocannons.[106] The autocannons were armored cars equipped with 37 mm cannons, with each group consisting of six armored cars or three autocannons.[107]

Other Fronts

[edit]Sub-Saharan Africa

[edit]In French West Africa (AOF), the general based in Dakar had very limited cavalry resources in 1914: the only squadron of Senegalese Spahis[note 22] (119 men, including 16 European officers) stationed in Saint-Louis had been deployed to Morocco since 1912.[108] Available forces included two mounted companies (each with about 100 riders and 130 horses) and 15 camel-mounted sections from the Senegalese Tirailleurs regiments (each section comprised 60 soldiers and 200 dromedaries).[note 23][109] Additional forces included mounted brigades from the indigenous guard—a paramilitary police force—such as the Timbuktu brigade on horseback or the Mauritania brigade, which used camels (where a mounted guard company of 80 to 100 Moors was created).[110] In French Equatorial Africa (AEF), only the indigenous Chad regiment had mounted components, with one squadron, two camel-mounted companies (200 men), and four camel-mounted sections (30 men each).[111]

The conquest of the German colonies of Togoland and Kamerun was conducted without cavalry support, as the tropical forest climate, poor road conditions, and limited food supply rendered it impractical:

"Animals were of no use to the column—not the packhorses nor the artillery mules. All transportation was carried out by porters" (report from the Kamerun expeditionary column, January 1, 1915).[112] Horses and mules were returned to Dakar by ship on January 9, 1915.[113] While the indigenous guard brigades from Dahomey and Ouagadougou sufficed for the invasion of Togo in August 1914, the Kamerun campaign lasted until 1916. The few mounted French troops in sub-Saharan Africa were used only for policing, with one exception: the mounted company of the 4th Senegalese Tirailleurs Regiment, tasked with maintaining a sanitary cordon around Dakar during a plague epidemic from May to autumn 1914.[114]

Saharan Territories

[edit]In Tunisia, the fort at Dehiba and surrounding posts were attacked by Tripolitans in September–October 1915, June 1916, October–November 1917, and August 1918. This prompted the continuous deployment of 15 battalions and eight squadrons (Chasseurs d'Afrique and Spahis) in southern Tunisia during this period.[115] In southern Algeria, the post at Djanet was attacked in March 1916 by groups coming from Ghadames (in Fezzan), forcing the French to evacuate both Djanet and Fort Polignac, which was abandoned on December 17, 1916. This led to revolts throughout the Hoggar and Tassili des Ajjers regions, with French goumiers and camel-mounted units (mainly Châamba recruits) regaining control only near the war's end. Fort Polignac and Djanet were reoccupied in late October 1918.[116]

In the Aïr region, Senussi leader Khoassen, coming from Ghat, besieged Agadez starting on December 7, 1916, massacring a camel-mounted section (54 men) on December 28, about 20 km to the east.[117] The French response included establishing the "Supreme Command of Saharan Territories" (spanning Algeria and AOF) on January 12, 1917, under General Laperrine,[118] and organizing military columns. While the siege of Agadez was lifted on March 3, 1917, guerrilla warfare persisted in the mountains until February 14–19, 1918, when Khoassen was defeated at Tamaclak (120 km north of Agadez).[119]

In Chad, groups from Kufra staged incursions. From May to July 1916, French columns restored order in the rebellious Ouadaï and Dar Sila regions (the British conducted similar operations in Darfur). However, French posts in Tibesti were evacuated in August 1916.[120]

Morocco

[edit]The other African theater of operations for French cavalry during World War I was Morocco. Since the establishment of the protectorate in 1912 (by the Treaty of Fes), numerous French units had been deployed there, but they occupied only the Moroccan plains (Chaouia, Gharb, and Saïs). The northernmost region was controlled by the Spanish, while the various populations of the Atlas Mountains remained completely autonomous. On August 1, 1914, the French occupation force numbered approximately 88,200 men, consisting of 64 battalions and 34 squadrons.[121] These included nine squadrons of chasseurs d'Afrique, 13 Algerian spahis, one Senegalese spahi, 11 Moroccan spahis ("Indigenous chasseurs"), and 14 mixed goums (company-sized units, partly mounted).[122] This powerful force was tasked with what the French referred to as "pacification."

Starting July 27, 1914, the French Resident-General in Morocco, General Lyautey, received orders from War Minister Messimy to send some of his troops to Europe, particularly the best infantry units (Zouaves, Foreign Legion, colonial infantry, etc.), leaving behind Moroccan auxiliaries and Senegalese riflemen.[123] On August 6, the "Marching Infantry Division of Morocco" was formed in Rabat, including two squadrons of the 9th regiment of Chasseurs d'Afrique. After French defeats in the Battle of the Frontiers, more units were dispatched in late August and early September, such as the marching regiment of chasseurs d'Afrique for the new 45th Infantry Division and the marching regiment of Moroccan spahis (RMSM) to reinforce Conneau's Corps. Between 1914 and 1918, a total of 20 squadrons and 52 battalions were sent to Europe, reducing the occupation force to 75,000 men by September 15, 1914.[124]

By October 1, 1914, the occupation force increased to 80,000 men, comprising 50 battalions and 28 squadrons: six of chasseurs d'Afrique, 15 of Algerian spahis, one of Senegalese spahis, six of Moroccan spahis, and 14 mixed goums.[125] By the end of the war in Europe, on July 1, 1919, total forces reached 97,700 men, including 62 battalions (with some Zouave and colonial infantry battalions returning) and 32 squadrons: four chasseurs, 22 Algerian spahis, one Senegalese, and five Moroccan. Additionally, there were 25 groups and several armored cars.[126] Efforts focused primarily on local recruitment to form Moroccan spahi and goumier units.

Eastern Army

[edit]Dardanelles

[edit]With the Ottoman Empire entering the war in October 1914 on Germany's side, the Allies decided during the winter of 1914–1915 to form the "Mediterranean Expeditionary Force" to capture Constantinople. Troops were provided mainly by the British (ANZAC, Marines, Indians, etc.), while the French contributed an infantry division assembled from depot troops (a total of 17,000 men). A full cavalry regiment was assigned to the French division (later the 17th Colonial Infantry Division): a new marching regiment of chasseurs d'Afrique (designated the 8th Regiment on July 28, 1915)[127] with four squadrons,[note 24] 31 officers, 715 men, 680 horses, 181 mules, and 26 wagons as of February 1915, along with the escort of General d'Amade (one officer, 16 men, and 18 horses).[128] They embarked in March 1915 at Bizerte and Philippeville, stopped at Malta, and arrived at Moudros (on the island of Lemnos).[129]

Following the naval failure in the Dardanelles Strait on March 18, French troopships anchored at Moudros between March 18 and 27, then set sail from March 25 to Alexandria. The cavalry remained there (at the Zahiria camp and later Victoria College, east of the city)[130] due to a lack of landing equipment (the infantry used rafts).[131] French troops disembarked at Koum-Kale (as a diversion on April 25–26) and later at Cape Helles without their cavalry (though the machine-gun section attached to the 6th Colonial Mixed Regiment participated on foot until April 15).[130]

Salonika

[edit]In 1915, a Franco-British intervention in the Balkans was decided to support Serbia and encourage Greece and Romania to join the war on the Allies' side. The first French soldiers landed in Salonika on October 5, 1915 (with the authorization of the Greek government). On the same day, during the Calais conference, Joffre agreed to send a total of three French infantry divisions and two cavalry divisions to Serbia under the command of General Sarrail, designated as the "Army of the Orient."[132] While the three infantry divisions arrived between October and November (one was taken from the Gallipoli Peninsula, which was completely evacuated on January 9, 1916), an order issued on October 17, 1915, canceled the deployment of cavalry divisions:[note 25][133] the region's mountainous terrain rendered large cavalry units impractical. Nonetheless, the African Light Infantry Regiment, which had been waiting in Egypt, and a divisional squadron[note 26][134] (the 122nd being the only one of the three divisions to have one) arrived.[135]

The terrain between Uskub, [[Gevgelija Municipality |Guevgueli]], the Greek border, and the Bulgarian border does not allow for the use of cavalry, and mounted artillery cannot move along most communication routes, which are merely tracks where infantry march in single file. Under these conditions, please replace the announced cavalry division with an infantry division, including alpine troops [...]

— Telegram from General Sarrail, Commander of the Army of the Orient, October 16, 1915, in Salonika.[136]

However, after Bulgaria entered the war and Serbia was defeated in the autumn-winter of 1915, the Army of the Orient, which had advanced into the Macedonian mountains, was forced to retreat southward, taking refuge in Greek territory (as Greece maintained its neutrality). In early December 1915, the 4th African Light Infantry Regiment and a horse artillery group arrived and, together with the 8th African Light Infantry Regiment, formed a cavalry brigade. This brigade was deployed to Dojran (on the Macedonian-Greek border) starting December 11 to act as a rearguard for the retreating army[137] and later to Koukouch to cover the entrenched camp at Salonika.[138] Sarrail requested two additional infantry divisions, a cavalry regiment, and artillery, but Joffre only provided cavalry and artillery. The 1st African Light Infantry Regiment landed in Salonika from February 2 to 5, 1916, and was sent to the western bank of the Vardar River along the route leading to Monastir.[139]

In March 1916, skirmishes began along the border; by April–May, the Army of the Orient engaged with the enemy. The 8th Infantry Regiment was dispersed in support of major infantry units, the 4th was stationed on the right flank in the Boutkova Valley, and the 1st on the left in the Moglenitsa region.[140]

On August 20, General Sarrail withdrew the 1st Regiment, two horse artillery batteries (on August 27), and the 4th Regiment (on September 6) from the Struma[141] detachment commanded by Colonel Descoins at the front. These units regrouped at the Zeitenlik camp (3 km north of Salonika).[142] Starting in September 1916, the Army of the Orient's attempted offensive was stalled by Bulgarian forces in the mountains, and the Macedonian front became static, transitioning into a trench warfare scenario in the mountainous terrain.

Albania and Thessaly

[edit]On October 2, 1916, the 1st Regiment was sent to Koritza to wrest Northern Epirus from Greek control and establish the Republic of Koritza. By December 1916, rising tensions with the Greek royal government necessitated defensive measures against a potential rear attack. On December 8, the 1st Regiment was withdrawn from the left flank and stationed at Kojani starting December 12 to guard against Thessaly with an armored car section monitoring Kalabaka and Trikala.[143] Tensions escalated in early 1917 with the Greek schism and the formation of a pro-Allied rebel Greek government. In March 1917, the Moroccan Spahi Regiment (RMSM)[note 27][144] reinforced the area. On May 25, 1917, four regiments were consolidated under Colonel Bardi de Fourtou to form a cavalry group, integrated into a provisional division (the Venel Division) on June 3, and assigned to oversee Thessaly.[144] On June 12, five French squadrons charged the royalist Greek garrison at Larissa. This mission concluded in August after the harvest.

The cavalry was redeployed to Albania around Koritza. The RMSM, detached to a new provisional division (Jacquemot Division), crossed the Devolli River and captured Pogradec, advancing on horseback and fighting on foot at the vanguard from September 8 to 12, 1917, capturing around 100 prisoners and two cannons.[145] After police missions in Albanian villages to confiscate weapons, the RMSM returned to the provisional division. On October 19, 1917, it flanked enemy lines (Bulgarian and Austrian) west of Lake Ohrid by crossing the Shkumbin gorges, climbing the ravines on the left bank,[145] and fighting on foot until October 22. The Spahis were withdrawn from the front on November 11, 1917, and placed in reserve.[146]

In February 1918, the Army of the Orient's Cavalry Brigade[147] was formed under General Jouinot-Gambetta, including the RMSM (stationed at Verria and Sorovitch), the 1st African Light Infantry Regiment (near Ostrovo and later at the Samorino camp north of Niaousta in April), and the 4th African Light Infantry Regiment (south of Bohemitsa and along the Larissa line). During the end of the winter truce (when snow prevented mountain combat), squadrons monitored the withdrawal of Russian troops to prevent their demotivation from spreading to others.[148] As of June 1, 1918, the Army of the Orient had 3,791 cavalrymen, a small number compared to the 232,299 French soldiers in the army (with British, Albanian,[note 28][149] Greek, and Italian forces bringing the total to 654,000 men).[150] On July 6, 1918, the RMSM was again deployed in Albania in the mountainous Bofnia region.

Franco-Serbian Offensive

[edit]In August 1918, in preparation for the offensive, the Moroccan Spahis were withdrawn from the front and sent to Kotori (south of Flórina). The 4th African Chasseurs were regrouped at Sakoulévo, while the 1st Chasseurs were tasked with transporting 155 mm shells in canvas bags on horseback between the Dragomantsi depot and Serbian batteries (where Decauville railways or cable cars were not installed) from August 14 to September 10.[151] On September 15, the day the offensive began, the three cavalry regiments of the brigade were assembled in the Monastir plain.

On September 20, Bulgarian troops began retreating in the Monastir plain. On the 23rd, the cavalry brigade followed the infantry and reached Prilep, abandoned by the enemy. On the 24th, contrary to orders (which were to continue directly north), the brigade crossed the Babouna Pass and captured Stepantsi on the 25th. With the crossing of the Vardar at Veles blocked (due to clashes between Serbian and Bulgarian forces), the brigade entered the Goleshnitsa mountain range, traversing it in four days via goat trails through Drenovo, Paligrad, and Dratchevo[152] to arrive above Üsküb (the Turkish name for Skopje) on September 29, 1918. The Moroccan Spahis captured 330 prisoners, including 150 Germans, five 105 mm howitzers, two 210 mm howitzers, 100 supply wagons, a grain train, livestock, and more.[153]

Palestine and Syria

[edit]In March 1917, a few French units were sent to Egypt to join the British forces in the Palestine campaign. This deployment was requested by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which aimed to include these units in the conquest of Syria, an Ottoman territory expected to fall under French influence per the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement.[154] Three infantry battalions formed the "French Detachment of Palestine" (DFP), commanded by Lieutenant Colonel (later Colonel) Philpin de Piépape (formerly commander of the 10th Chasseurs). The modest cavalry component consisted of a platoon from the 1st Spahis of Biskra,[note 29][155] delayed in Bizerte due to mumps cases in April 1917. This unit embarked on June 1, disembarked at Port Said on June 10,[156] and joined the DFP at Khan Younous (Khan Younis, near Gaza) on June 15. The detachment's role was limited to securing communication routes in the Sinai. It advanced in November to Deir Sineid[157] and moved to Ramleh in December 1917 to protect the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway line.

As diplomats pushed for combat involvement, the detachment was reinforced with Armenian and Syrian volunteers (the "Legion of the Orient") and additional cavalry units.[158] On March 19, 1918, reinforcements, including the 5th and 6th squadrons of the 4th African Chasseurs and three platoons of the 1st Spahis, arrived at Port Said.[159] A final reinforcement group, the 5th squadron of the 4th Tunisian Spahis from Sfax, faced disaster when their British horse transport ship, the SS Hyperia, was sunk by a German submarine (UB-51)[160] on July 28, 1918, 84 nautical miles northwest of Port Said.[161] All horses and 19 riders perished.[162] This formed the "Mixed Cavalry Regiment of the French Detachment of Palestine-Syria" under Squadron Commander Lebon,[163] with three mounted squadrons, one dismounted squadron, and a machine-gun platoon.[164] On March 27, 1918, the combined infantry, cavalry, artillery, and engineering units were designated the "French Detachment of Palestine-Syria" (DFPS).[165]

In July, the French infantry regrouped at Mejdel and, by August 29–31, were on the front lines with the British 21st Corps, facing Turkish trenches at Rafat. Between August 19 and 24, the cavalry regiment joined the Australian 5th Light Horse Brigade in the Australian Mounted Division at Surafend.[166] By September 1, the regiment had 25 officers (23 European) and 692 men (517 European).[167]

On September 19, 1918, the British 21st Corps launched an offensive in the Sharon Plain. The French cavalry regiment quickly broke through, capturing Tulkarem, 1,800 prisoners, 17 guns (including Austrian batteries), and 18 machine guns.[163][168][169] On September 21, the regiment entered Nablus after a charge through its gardens and streets, seizing 900 prisoners, three guns, and nine machine guns,[163] with only seven wounded and losses of horses replaced by Turkish captures.[170] It reached Jenin on September 22,[171] Nazareth on the 25th, Tiberias on the 26th, and crossed the Jordan on the 27th,[163] encircling Ottoman forces in Galilee. On September 29, it fought near Sasa and blocked roads and railways west and north of Damascus, ambushing retreating Turkish columns.

The French entered Douma on October 1, 1918, while British and Arab forces entered Damascus.[172] On October 2, a mixed squadron joined the Allied ceremonial entry into Damascus.[163] The unit cleared remaining fugitives around the city until October 4.[173] Afterward, eight cavalrymen died in Damascus hospitals.[163]

On October 15, the Ottoman Empire requested an armistice, signed on October 31 at Mudros. Philpin de Piépape was appointed military governor of Beirut on October 8. The dismounted squadron embarked from Haifa on October 9 and landed in Beirut on the 11th to take on police duties.[174] The mixed cavalry regiment left Damascus on October 20 to rejoin the detachment in Beirut by October 24. By the end of October, cavalry units were deployed to Merdj Adjoun, Hasbaya, Rachaya, and Baalbek.[175] On November 12, a cavalry platoon and a battalion of riflemen landed in Alexandretta.[176] On November 16, another cavalry platoon was stationed in Tripoli.[177] By January 5, 1919, two squadrons, including the dismounted one, were in Beirut; other units were stationed in Latakia, Alexandretta, Tripoli, Sidon, and Djedeide. By February 1919, a platoon was garrisoned in Jerusalem. Renamed the "Mixed Cavalry Regiment of the Levant," then the "1st Cavalry Regiment of the Levant" on October 22, 1920,[163] its detachments participated in the Cilicia conflict as part of the Levant Army starting in July 1919.

After the Armistices

[edit]The four armistices (one for each defeated power: with Bulgaria on September 29, 1918, the Ottoman Empire on October 30, Austria-Hungary on November 3, and Germany on November 11) were only temporary ceasefires. The state of war persisted until the promulgation of the various peace treaties: Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919; Saint-Germain on September 10; Neuilly on November 27; Trianon on June 4, 1920; and Sèvres on August 10, 1920. It was the cavalry regiment of the Republican Guard that rendered honors to the delegations and maintained order during the Paris Conference.[33] The cavalry was involved in the final operations due to its mobility and the fact that it consisted primarily of career soldiers, while the rest of the army began demobilizing.

March to the Rhine

[edit]

The armistice of November 11, 1918, stipulated not only a ceasefire but also the evacuation by the German army within 15 days of the occupied territories (Belgium, France, and Luxembourg) and Alsace-Lorraine. Within another 15 days, German forces were required to withdraw from the Rhineland up to 10 km beyond the right bank of the Rhine, allowing the Allies to occupy these territories.[178] This armistice was initially valid for only 36 days (until December 17, 1918), but it was extended for a month on December 13, 1918, and again on January 16, 1919, eventually remaining indefinite as the peace treaty negotiations continued.

French troops crossed the front lines starting November 17, following the German retreat at a distance of only ten kilometers, stopping at six successive lines.[179] In Alsace-Lorraine, assigned to Fayolle's army group (the former reserve army group), the 5th Cavalry Division advanced with the 10th Army, while the 3rd Cavalry Division was integrated into the 33rd Army Corps. In Belgium's Ardennes, under the command of Maistre's army group (the former Central Army Group), the 2nd Cavalry Division was placed under the 6th Army, while the 2nd Cavalry Corps (reduced to the 4th and 6th Cavalry Divisions) remained independent. By November 30, all of Alsace-Lorraine had been reoccupied.

From December 5 to 13, 1918, Allied troops advanced to occupy the Rhineland. On the left bank of the Rhine, the French zone extended from Lauter to Bingen, the American zone to Bonn, the British zone to Düsseldorf, and the Belgian zone to the Dutch border. On the right bank, three bridgeheads, each with a 30 km radius, were established between December 13 and 17 around Mainz, Koblenz, and Cologne.[180] This occupation, funded by the German government, was carried out by sixteen army corps (including 40 infantry divisions), of which six were French (18 divisions) and three were cavalry divisions (two French). The 3rd Cavalry Division was stationed west of Mainz, and the 4th southwest of Koblenz (in the American zone), as "bridgehead reserves."[181]

Demobilization and Occupation

[edit]The demobilization of the French Army was carried out by successive age groups, starting in December 1918 (class of 1890) and continuing until September 1919 (class of 1917). The gradual reduction in troop numbers led to several reorganizations, with regiments in all branches being dissolved. As of August 1, 1921, the French cavalry in mainland France consisted of 53 regiments (six cuirassiers, 25 dragoons, seven hussars, and 15 chasseurs à cheval): 30 were grouped into five cavalry divisions, 22 were attached individually to army corps, and one (the 8th Hussars) was stationed at the Kehl bridgehead.[182]

The occupation of the Rhineland (primarily the left bank) was soon assigned, within the French zone, to the newly created "Army of the Rhine," recalling the revolutionary era and composed of the French 8th and 10th Armies. The occupation of the Ruhr, from 1923 to 1926, was carried out by French infantry divisions and some Belgian units, along with the 4th Cavalry Division, which had its headquarters in Düsseldorf.[183]

-

The French cavalry in Gelsenkirchen in March 1923.

-

Entrance to the city of Essen.

Continued Mechanization

[edit]The role played by motorized/armored cavalry in operations during the First World War was relatively minor, not only due to its very limited and inefficient resources but also because of the prolonged stalemate of trench warfare and the inevitable need to 'learn by doing' regarding mobile operations. However, with hindsight, we can trace the evolution of this experience into the future armored car regiments, mixed cavalry divisions, and light mechanized divisions of the 1930s.

— General Lescel, Birth of Our Armored Army.[184]

From October 1918 onward, the production of armored cars on White TBC truck chassis began: 230 units were deployed to replace outdated equipment. The number of mixed groups of armored cars and autocannons (GAMAC) was reduced from 17 to 11, renamed "Cavalry Armored Car Squadrons" (EAMC) on November 1, 1922, and assigned to the five cavalry divisions, with each receiving two or three squadrons.[93]

On December 14, 1927, a session of the Superior War Council was devoted to the organization of the cavalry. Marshal Foch stated, "There are no longer cavalry divisions but light divisions. Weapons need to be transported quickly. They are transported on horseback, by bicycle, or in trucks—we are evolving." General Maurin questioned whether "cavalry is still a rapid maneuver element today," noting that "paved roads now constitute a serious obstacle for horse movement [...]. We must fully embrace motorization. Vehicles are not affected by gas attacks." Mounted troops were defended by Generals Niessel and Weygand; ultimately, the council decided to retain horse-mounted units until motorization could be completed.[185]

This motorization (using trucks and motorcycles) and mechanization (with armored cars and tanks) of the cavalry during the interwar period faced resistance from the infantry, which had held a monopoly on tanks since 1920 (previously assigned to the "assault artillery"). Only armored cars were permitted for cavalry units. Thus, "combat armored cars" (AMC), essentially cavalry tanks, were ordered. The cost of mechanization, combined with the conservatism of horse-mounted advocates (such as General Weygand, who feared fuel shortages),[185] led to the continued existence of many horse-mounted squadrons, intended for medium-term mechanization. Light cavalry regiments were now expected, in the event of mobilization, to form reconnaissance groups for divisions (GRDI) and army corps (GRCA). The five cavalry divisions were to be transformed during mobilization into "light cavalry divisions," composed of one mechanized brigade and one mounted brigade, following the principle of a "manure and grease" mix. Cyclist hunter groups (formed by chasseurs à pied battalions) were replaced by mounted dragoon battalions (using trucks or buses), which served as infantry support for divisions. This gradual motorization prevented the cavalry from disappearing as a branch, even though horseback combat had become obsolete.[185]

In July 1935, the 4th Cavalry Division was fully mechanized and renamed the 1st Light Mechanized Division, under General Flavigny, a leading advocate of armored cavalry. A few months later, in October 1935, the 3rd Cavalry Division of the German Army was also mechanized, becoming the 1st Panzer Division (the first armored division). In France, the creation of the 1st Armored Division would not occur until January 1940.

Distinctions

[edit]The following regiments were awarded the fourragère after the conflict:[186]

- Fourragère in the colors of the ribbon of the Médaille Militaire (4–5 citations at the Army level):

- Régiment de Marche de Spahis Marocains (RMSM) (5 citations), the most decorated cavalry regiment in the French Army (24/12/1918).

- Fourragère in the colors of the ribbon of the Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 (2–3 citations at the Army level):

- 1st and 4th Régiments de Chasseurs d'Afrique

- 5th, 11th, 15th, 17th, and 18th Régiments de Chasseurs à Cheval

- 3rd, 4th, 8th, 9th, 12th, 14th, 15th, 16th, 20th, 22nd, 29th, and 31st Régiments de dragoons

- 4th, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 11th, and 12th Régiments de Cuirassiers

- 3rd Régiment de Hussards

See also

[edit]- Plan XVII

- French Army order of battle (1914)

- Battle of the Frontiers

- Horses in World War I

- Horses in warfare

- Battle of Halen

- German cavalry in World War I

- British cavalry during the First World War

Notes

[edit]- ^ The height of the riders was theoretically to be between 1.59 and 1.68 metres in the light cavalry for a weight limited to 65 kg, in the dragoons between 1.64 and 1.74 m for no more than 70 kg and the cuirassiers between 1.70 and 1.85 m with a maximum of 75 kg. For farriers, saddlers, armourers and tailors of the light regiments, the minimum height was lowered to 1.56 m.

- ^ For example, in Libourne in the 18th military region, the 15th Dragoons and part of the 57th RI were stationed: at the beginning of August 1914, the cavalry regiment had a total of 32 officers (4.5% of the total number of personnel) and 59 non-commissioned officers (8.3%) for 619 brigadiers and cavalrymen, compared to 60 officers (1.8%) and 179 non-commissioned officers (5.4%) for 3,039 corporals and soldiers in the infantry regiment.

- ^ In the event of enlistment, the volunteer has the choice of his assigned weapon, as well as a bonus of 125 F and a high pay of 0.4 F per day after two years of service.

- ^ The proportion among officers of those with a noble-sounding name would be 10% in the infantry and 20% in the cavalry.

- ^ The French cavalry used several models of sabres in 1914: the 1854 model (straight blade one metre long) transformed 1882 (shortened to 950 mm for the cuirassiers, or a mass of 1.34 kg without the scabbard, and to 925 mm for the dragoons, or 1.32 kg) for the heavy cavalry; the 1822 model (curved blade of 920 mm) transformed 1884 (shortened to 870 mm and to a single strap on the scabbard to be worn in the saddle) and the 1822 model transformed 1883 (straight blade shortened to 870 mm, or 1.080 kg) for the light cavalry. The 1882 and 1896 model sabres, considered not strong enough, were only used for training. The officers are theoretically equipped with the model 1896 and model 1822/1882 sabres respectively, but as they arm themselves at their own expense, they often obtain their supplies from private suppliers who only take inspiration from the regulatory models.

- ^ The Cavalry Committee and its president, General de Galliffet, had recommended in their 1881 report the abolition of the cuirass, an abolition applied until 1883 for half of the regiments (those with even numbers).

- ^ In addition to the four squadrons (sometimes more in the African army), there is the staff platoon (PEM), the non-ranking platoon (PHR) comprising the necessary specialists (farrier and his assistant farriers, saddler, wigmaker acting as hairdresser-barber, etc.), as well as a depot squadron.

- ^ The Guard Guides form the 9th Hussars, the Guard Horse Chasseurs the 13th Chasseurs, the Empress Dragoons the 13th Dragoons, the Guard Lancers the 9th Lancers, the Guard Carabiniers the 11th Cuirassiers and the Guard Cuirassiers the 12th Cuirassiers.

- ^ The remains of the 1st Lancer Regiment were transferred to the 14th Chasseurs, the 2nd was transformed into the 10th Hussars, the 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 8th and 9th Lancers became the 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Dragoons, while the 7th formed the 14th Chasseurs.

- ^ The spahi regiments have the particularity of being made up of five, six or nine squadrons, for a total of 25 spahi squadrons. A 5th spahi regiment was formed on August 1, 1914 by splitting the 2nd. Added to this were a squadron of Senegalese spahis and 12 squadrons of Moroccan auxiliaries (which later became the Moroccan spahis).

- ^ During the Russo-Japanese War, observed on the spot by officers of the other powers serving as military attachés, a Russian detachment armed with six Madsen machine guns (called "cavalry machine guns") had cut to pieces an entire Japanese infantry regiment during the Battle of Mukden. The episode is recounted in a report by General Samsonov, published in Le Temps on March 4, 1908 and then in the Revue d'artillerie in 1912 (volume 81).