Socialism in Libya

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Socialism in Libya has been created by the ideologies and policies of Muammar Gaddafi, who ruled the country from 1969 until 2011. His political philosophy was largely written in "The Green Book", which presents a third universal theory alternative to capitalism and communism.[1]

Historial context

[edit]Pre-Gaddafi era

[edit]

Before Gaddafi's rise to power, Libya was a monarchy under King Idris I. He led the country to independence from colonial rule. He faced several problems during his reign in power, such as poverty, bad infrastructure and high unemployment and illiteracy rates.[2] Libya was divided into three regions—Tripolitania, Fezzan, and Cyrenaica—with a weak central government. The economy was underdeveloped, except for the oil sector and there were significant regional disparities in wealth and access to services. Although he did expand the oil sector in Libya, his reign was plagued by political instability and mismanagement.[3] Oil revenues were spent on family and tribal alliances that supported the monarchy, rather than on building the economy and improving life in Libya. In 1969, during his trip to Turkey for medical reasons, a coup d'état was launched in Benghazi, with the leadership of Muammar Gaddafi.[4]

1969 Libyan Revolution

[edit]Muammar Gaddafi, leading 70 troops from the Free Unionist Officers Movement—mostly enlisted men from the Signal Corps—gained control of Benghazi. Within two hours, they had seized the entire government, effectively abolishing the Libyan monarchy. This event, known as the Al Fateh Revolution, marked a significant turning point for Libya. Influenced by Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser's pan-Arabism, Gaddafi overthrew the government.[5]

The coup was relatively bloodless and quickly gained support among various factions within Libya, including the military and the general public, who were discontent with Idris's rule. Gaddafi's early promises of social reform, wealth redistribution, political change and strong support for the Palestinian cause[6] appealed to a wide audience, setting the stage for the radical transformations that would follow under his rule[7]

Establishment of the Jamahiriya

[edit]Gaddafi's vision for Libya culminated in the establishment of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya in 1977, a "state of the masses" that was meant to reflect his theoretical proposals in The Green Book.[8] This new state structure aimed to replace traditional institutions with direct forms of democracy as articulated through people's congresses and committees. Gaddafi criticized the parliamentary structure, by calling it dictatorial and came up with a new government system. The new system sought to engage every citizen in the decision-making process, thereby dismantling the old bureaucratic structures and the influence of traditional elites

The Green Book

[edit]

The Green Book by Muammar Gaddafi serves as the theoretical cornerstone of his distinctive brand of socialism in Libya. It outlines a detailed philosophy against traditional capitalism and communism, proposing instead a system that Gaddafi called the "Third Universal Theory." This theory was meant to be practical and directly applied through three distinct aspects: politics, economy, and society.[9]

Political aspects

[edit]The Green Book criticizes traditional forms of democracy and dictatorship. It argues that representative democracy, as practiced in much of the world, is a disguise for dictatorship because it centralizes power in the hands of a few instead of the many. Instead, Gaddafi proposed a system of direct democracy that he called 'People's Congresses and Committees'. According to Gaddafi, in this system, there is no need for a parliamentary system, as every adult Libyan citizen is participating in the decision making process every and thus preventing the corruption and alienation associated with parliamentary systems.[10] The ideal was for local communities to form committees that would meet in larger congresses to make decisions that affect their areas and the country as a whole.

Economic aspects

[edit]Economically, The Green Book proposes a radical restructuring of ownership and production. Gaddafi argued against private ownership that leads to wealth being controlled by a few individuals or corporations. Instead, he advocated for the means of production—such as land, natural resources, and large industries—to be held in common by all people. This part of the idea sought to guarantee that the riches derived from these resources would benefit every citizen equally and to stop economic exploitation. Practical steps taken included redistributing land to the population and nationalizing major industries, particularly oil, which is Libya's most valuable resource.

Social aspects

[edit]On the social front, Gaddafi's book challenges the traditional family structure and the societal norms that dictate individual roles. It calls for a social revolution that emphasizes self-reliance, education, and the breakdown of the patriarchal family model. Gaddafi envisioned a society where men and women are equal, and where children are raised to understand and practice these values from a young age. His social policies also included the importance of universal education and healthcare as fundamental rights, ensuring that every citizen receives these benefits and participates in the development of the country.[11]

Implementation of socialism

[edit]Following the establishment of his regime, Muammar Gaddafi began implementing a series of radical reforms intended to transform Libyan society according to the socialist and populist ideologies laid out in The Green Book. His government took several decisive steps

Economic policies

[edit]Nationalization of the oil sector

[edit]Shortly after taking power, Gaddafi took control of the oil industry from foreign companies and nationalized it. This move allowed the Libyan government to gain significant revenue, which was purportedly redistributed to improve public services such as healthcare, education, and housing.

Agricultural reforms

[edit]Gaddafi launched land reform policies aimed at breaking up large privately-owned estates and redistributing the land to the landless and poor. This was part of a broader initiative to promote self-sufficiency in food production and to weaken the power of the traditional elite who owned much of the country's arable land.

Economic diversification

[edit]Efforts were made to diversify the economy away from heavy reliance on oil by developing other sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and tourism. These initiatives were met with little success, as the oil sector continued to dominate the economy.[12]

Social policies

[edit]Housing and infrastructure development

[edit]One of Gaddafi's most notable policies was the declaration that housing is a basic human right. His government embarked on extensive construction of new housing units and infrastructure projects to improve living conditions and modernize the country's infrastructure.

Education

[edit]Education was made free at all levels, from primary school to higher education. This policy was aimed at ensuring that every Libyan had access to education regardless of their background. There was a particular emphasis on female education, which Gaddafi promoted as part of his broader agenda to empower women and promote gender equality in Libyan society. Gaddafi's regime also expanded technical and vocational education programs. These were designed to align with Libya's economic diversification efforts and reduce foreign labor dependency.[13]

Healthcare

[edit]Healthcare services were provided free of charge to all citizens. This included everything from routine check-ups to complex surgeries and was part of a broader vision to improve the general welfare of the population. The government invested heavily in healthcare infrastructure, building hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare facilities across the country. This expansion was intended to make healthcare accessible to everyone, including those in rural and underserved areas. Public health campaigns were regularly conducted to educate the population on various health issues, including vaccinations, maternal health, and chronic diseases. These efforts were successful as the number of hospitals in the country increased and infant mortality rates drastically decreased.[14]

General People's Committees

[edit]The General People's Committees were a central element of Muammar Gaddafi's governance structure in Libya, designed to implement his vision of direct democracy. These committees, established at local levels across the country, managed daily administrative tasks and local policy implementation, aiming to empower communities and reduce bureaucratic inefficiencies. They also played a crucial role in social mobilization, encouraging citizen participation in state-led projects. Politically, the committees facilitated direct participation through local congresses where decisions were made by consensus or majority vote, embodying Gaddafi's rejection of representative democracy. This system aimed to decentralize power, giving every citizen a direct voice in governance, aligned with the principles outlined in Gaddafi's Third Universal Theory, which advocated for a 'state of the masses' (Jamahiriya) where authority was exercised by the people without political parties. This government structure, however, did not lead to the intended results, instead leading to a dictatorship with Gaddafi and his advisers making all of the decisions.[15]

Failures

[edit]Muammar Gaddafi's rule over Libya, while marked by ambitious reforms, was also characterized by significant failures that had lasting impacts on the country. These failures spanned political, economic, social, and international relations spheres.

Political

[edit]Human rights

[edit]

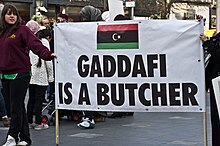

Gaddafi's government was notorious for its human rights abuses. The regime suppressed any form of dissent through severe censorship, arbitrary detentions, and often brutal repression. Political parties were banned, and the legal system was heavily manipulated to serve the regime's interests, undermining the rule of law and leading to widespread human rights violations.[16]

Instability of government institutions

[edit]Gaddafi promoted a system he called "direct democracy", but in practice, this resulted in a highly centralized form of governance with power concentrated in his hands. The lack of institutions capable of sustaining governance without his personal leadership left Libya with constant instability and conflict.

Economic

[edit]While Libya was rich in oil, the wealth was poorly managed and often squandered on grandiose projects that did not yield substantial economic returns, such as the Great Man-Made River. Critics of this irrigation system, claim that the technology used for it is not sustainable.[17] Corruption was rampant, with much of the country's wealth being diverted into the hands of Gaddafi and his close associates. This mismanagement resulted in inadequate development of vital infrastructure outside the oil sector and significant economic inequalities. The failure to develop other sectors of the economy meant that Libya did not build the foundations necessary for long-term economic stability.

Social

[edit]Although Gaddafi made education and healthcare accessible, the quality of these services often remained poor. Educational systems focused more on ideological indoctrination than on critical thinking or practical skills, and healthcare facilities suffered from mismanagement and lack of resources, particularly in rural areas. Libya had a shortage of teachers and nurses, so new schools and hospitals were understaffed.[18]

International relations

[edit]International isolation

[edit]For much of his rule, Gaddafi's foreign policy decisions isolated Libya from much of the international community. His support for various extremist groups and involvement in international terrorism led to sanctions and diplomatic isolation. Although there was some hope for diplomatic relations in the 2000s, his earlier actions had long-lasting effects on Libya's international relations.

Pan-Arab and pan-African ambitions

[edit]Gaddafi styled himself as a leader with Pan-Arab and later Pan-African ambitions, but his efforts to lead regional unification were largely unsuccessful. His erratic behavior and the authoritarian nature of his rule made other countries wary of his leadership, ultimately limiting his influence in the region.[19]

Impact and legacy

[edit]Impact on Libyan society

[edit]Gaddafi's rule saw significant social engineering, including efforts to uplift women's rights under a conservative regime and promote literacy and education. However, the quality of education remained lacking, with a focus on ideological indoctrination over critical thinking skills. On the cultural front, Gaddafi sought to reshape Libyan identity around his Third Universal Theory, impacting generations' views on governance and society.[20]

Economic mismanagement

[edit]Libya under Gaddafi exploited its vast oil reserves to fund the state and its welfare programs. However, the economy remained heavily dependent on oil, with little successful diversification. After his fall, the lack of a diversified economic foundation meant that Libya struggled with economic instability exacerbated by political chaos. Wealth distribution also remained a major issue during Gaddafi's reign. Although the oil sector brought in a vast amount of capital, it did not all layers of society. Much of this wealth was shared between Gaddafi and his inner circle.

Political legacy

[edit]Government institutions

[edit]One of Gaddafi's most critical legacies was the absence of robust political institutions. His revolutionary system of direct democracy, the Jamahiriya, effectively dismantled pre-existing structures but failed to provide a stable or sustainable alternative. This has left Libya grappling with a power vacuum, struggling to build a cohesive state framework post-Gaddafi.

Instability

[edit]The political void after Gaddafi's fall in 2011 led to ongoing instability and conflict, with various factions vying for power. The lack of strong institutions and a history of centralized authority under Gaddafi have made the transition to a stable governance structure particularly challenging.[21]

International legacy

[edit]Muammar Gaddafi's international legacy is complex, marked by his shifting alliances, support for revolutionary movements, and his ideological campaigns across different regions. His reign and eventual downfall elicited a range of reactions from various parts of the world, reflecting the controversial nature of his foreign policy and his impact on global politics.

Africa

[edit]Gaddafi was a prominent advocate for African unity, envisioning a united continent that could stand on equal footing with the West. He was instrumental in the founding of the African Union (AU) in 2002 and supported African liberation movements financially and militarily. His vision for a "United States of Africa" aimed to elevate the continent's global standing. However, reactions to his downfall were mixed. While some African leaders viewed him as a champion of anti-imperialism and pan-Africanism, others saw his fall as a relief, considering him a divisive figure whose economic influence had been a double-edged sword for many countries that relied on his support.[22]

Arab world

[edit]In the Arab world, Gaddafi initially sought to position himself as a leader of pan-Arabism, proposing political unions with Egypt, Tunisia, and Syria, although these efforts never materialized.[23] His rhetoric often called for Arab unity against perceived Western imperialism and Zionism. Despite his ambitious regional goals, Gaddafi's relationships with other Arab leaders were fraught with tension, and his unpredictable political maneuvers often isolated him. During the Arab Spring, many Arab states quickly accepted his fall, with some even supporting NATO intervention, viewing his removal as an opportunity to re-establish stability and recalibrate alliances.

Western world

[edit]Gaddafi's relationship with Western countries was highly contentious, especially during the decades when he supported international terrorism, including the infamous Lockerbie bombing in 1988.[24] This led to severe UN sanctions. In the 2000s, Gaddafi sought to rehabilitate his image by abandoning weapons of mass destruction programs and denouncing terrorism, which led to normalized relations with many Western nations. The West's reaction to his downfall was generally favorable, with countries like the United States, United Kingdom, and France playing active roles in the NATO-led military intervention that helped topple his regime. They viewed his removal as the end of a notorious dictatorship and a step forward for the promotion of democracy and stability in North Africa.

References

[edit]- ^ "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Vandewalle, Dirk J. (2006). A history of modern Libya. Internet Archive. Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85048-3.

- ^ John, Ronald Bruce St (2012-04-01). Libya: From Colony to Revolution (2nd Edition, Revised ed.). Oxford: Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1-85168-919-4.

- ^ "1969: Bloodless coup in Libya". 1969-09-01. Retrieved 2024-04-24.

- ^ Abushagur, Soumiea (2011). The Art of Uprising: The Libyan Revolution in Graffiti. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-105-15535-2.

- ^ Bearman, Jonathan (1986). Qadhafi's Libya. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-0-86232-434-6.

- ^ Vandewalle, Dirk (2018-09-05). Libya since Independence. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-3236-2.

- ^ "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-04-26.

- ^ "The Green Book". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 2024-04-26.

- ^ "The Muammar Gaddafi story". BBC News. 2011-03-26. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Libya : a country study | WorldCat.org". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Harris, Lillian C. (1986-10-27). Libya: Qadhafi's revolution and the modern state. Profiles, Nations of the contemporary Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0075-7.

- ^ Vandewalle, Dirk J. (2006). A history of modern Libya. Internet Archive. Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85048-3.

- ^ Bearman, Jonathan (1986). Qadhafi's Libya. London; Atlantic Highlands, N.J: Zed Books. ISBN 978-0-86232-433-9.

- ^ Vandewalle, Dirk J. (2006). A history of modern Libya. Internet Archive. Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85048-3.

- ^ "Factbox: Gaddafi rule marked by abuses, rights groups say". Reuters. 2011-02-22. Retrieved 2024-10-12.

- ^ "Great Man-Made River (GMR) | History, Construction, Map, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Alnaas, Mohammed (2022-06-04). "Libya: the Teacher Leader and 'Free' Education - Culturico". culturico.com. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Alnaas, Mohammed (2022-06-04). "Libya: the Teacher Leader and 'Free' Education - Culturico". culturico.com. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Time running out for cornered Gaddafi". ABC News. 2011-02-23. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "About this Collection | Country Studies | Digital Collections | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ Ap (1990-03-25). "Egyptian and Syrian Leaders Meet With Qaddafi in Libya". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "U.S./UK Negotiations with Libya regarding Nonproliferation". The American Journal of International Law. 98 (1): 195–197. 2004. doi:10.2307/3139281. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 3139281.