Foreskin restoration

Foreskin restoration or reconstruction refers to the process of recreating the foreskin of the penis, which has been removed by circumcision or injury. Foreskin restoration is primarily accomplished by stretching the residual skin of the penis, but surgical methods also exist. Restoration creates a facsimile of the foreskin, but specialized tissues removed during circumcision cannot be reclaimed. Some forms of restoration involve only partial regeneration in instances of a high-cut wherein the circumcisee feels that the circumciser removed too much skin and that there is not enough skin for erections to be comfortable.[1]

History

[edit]In the Greco-Roman world, uncircumcised genitals, including the foreskin, were considered a sign of beauty, civility, and masculinity.[2] In Classical Greek and Roman societies (8th century BC to 6th century AD), exposure of the glans was considered disgusting and improper, and did not conform to the Hellenistic ideal of gymnastic nudity.[2] Men with short foreskins would wear the kynodesme to prevent exposure.[3] As a consequence of this social stigma, an early form of foreskin restoration known as epispasm was practiced among some Jews in Ancient Rome (8th century BC to 5th century AD).[4]

Foreskin restoration is of ancient origin and dates back to the Alexandrian Empire (333 BC). Males participated in the gymnasium nude and because the Greeks did not practice circumcision anyone who was circumcised was socially shunned. Hellenized Jews stopped circumcising their sons to avoid persecution and so they could participate in the gymnasium. Some Jews at this time attempted to restore their foreskins. This caused conflict within Second Temple Judaism, some Jews viewed circumcision as an essential part of the Jewish identity (1 Maccabees 1:15).[5] Following the death of Alexander, Judea and the Levant was part of the Seleucid Empire under Antiochus Epiphanes (175-164 BC). Antiochus outlawed the Jewish practice of circumcision, both 1st and 2nd Maccabees records Jewish mothers being put to death for circumcising their sons (1:60-61 and 6:10 respectively).[6] Some Jews during Antiochus' persecution sought to undo their circumcision.[7] Within the 1st century A.D., there was still some forms of foreskin restoration being sought after (1 Corinthians 7:18). During the third Jewish-Roman Wars (AD 132–135), the Romans had renamed Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolian and may have banned circumcision; however, Roman sources from the period only mention castration and say nothing about banning circumcision. During the Bar Kokhba revolt, there is Rabbinic evidence that records, Jews who had removed their circumcision (meaning that foreskin restoration was still being practiced) they were recircumcised, voluntarily or by force.[8] Again, during World War II, some European Jews sought foreskin restoration to avoid Nazi persecution.[9]

Non-surgical techniques

[edit]Tissue expansion

[edit]Non-surgical foreskin restoration, accomplished through tissue expansion, is the more commonly used method.[10]

Tissue expansion has long been known to stimulate mitosis, and research shows that regenerated human tissues have the attributes of the original tissue.[11]

Methods and devices

[edit]During restoration via tissue expansion, the remaining penile skin is pulled forward over the glans, and tension is maintained either manually or through the aid of a foreskin restoration device.[12]

-

Dual tension restorer applied to a circumcised penis for non-surgical foreskin restoration

-

T-tape with a leg strap

-

Silicone device with a one-way valve that allows air to be pumped to inflate and expand the foreskin.

-

Application of a typical restoration device, the TugAhoy, called a 'Chinese puzzle' by its inventor

Surgical techniques

[edit]Foreskin reconstruction

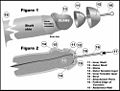

[edit]Surgical methods of foreskin restoration, known as foreskin reconstruction, usually involve a method of grafting skin onto the distal portion of the penile shaft. The grafted skin is typically taken from the scrotum, which contains the same smooth muscle (known as dartos fascia) as does the skin of the penis. One method involves a four-stage procedure in which the penile shaft is buried in the scrotum for a period of time.[13]

Results

[edit]Physical aspects

[edit]

Restoration creates a facsimile of the prepuce, but specialized tissues removed during circumcision cannot be reclaimed.[medical citation needed] Surgical procedures exist to reduce the size of the opening once restoration is complete (as depicted in the image above),[14] or it can be alleviated through a longer commitment to the skin expansion regime to allow more skin to collect at the tip.[15]

The natural foreskin is composed of smooth dartos muscle tissue (called the peripenic muscle[16]), large blood vessels, extensive innervation, outer skin, and inner mucosa.[17]

The process of foreskin restoration seeks to regenerate some of the tissue removed by circumcision, as well as provide coverage of the glans. According to research, the foreskin comprises over half of the skin and mucosa of the human penis.[18]

In a survey restorers reported restoration; increased their sexual pleasure for 69% and improved their relationship for 25% [19]

Organizations

[edit]Various groups have been founded since the late 20th century, especially in North America where circumcision has been routinely performed on infants. In 1989, the National Organization of Restoring Men (NORM) was founded as a non-profit support group for men undertaking foreskin restoration. In 1991, the group UNCircumcising Information and Resource Centers (UNCIRC) was formed,[20] which was incorporated into NORM in 1994.[21] NORM chapters have been founded throughout the United States, as well as in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, and Germany. In France, there are two associations about this. The "Association contre la Mutilation des Enfants" AME (association against child mutilation), and more recently "Droit au Corps" (right to the body).[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Lerman SE, Liao JC (December 2001). "Neonatal circumcision". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 48 (6): 1539–57. doi:10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70390-4. PMID 11732129.

- ^ a b

Circumcised barbarians, along with any others who revealed the glans penis, were the butt of ribald humor. For Greek art portrays the foreskin, often drawn in meticulous detail, as an emblem of male beauty; and children with congenitally short foreskins were sometimes subjected to a treatment, known as epispasm, that was aimed at elongation.

— Jacob Neusner, Approaches to Ancient Judaism, New Series: Religious and Theological Studies (1993), p. 149, Scholars Press. - ^ Hodges FM (2001). "The ideal prepuce in ancient Greece and Rome: male genital aesthetics and their relation to lipodermos, circumcision, foreskin restoration, and the kynodesme". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (3). Johns Hopkins University Press: 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485. S2CID 29580193.

- ^ Rubin JP (July 1980). "Celsus' decircumcision operation: medical and historical implications". Urology. 16 (1): 121–4. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4. PMID 6994325.

- ^ Barry, John D., David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Mangum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder, eds. The Lexham Bible Dictionary. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

- ^ Aymer, Margaret. “Acts of the Apostles.” In Women’s Bible Commentary, edited by Carol A. Newsom, Jacqueline E. Lapsley, and Sharon H. Ringe, Revised and Updated. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012.

- ^ Kaiser, Walter C., Jr., Peter H. Davids, F. F. Bruce, and Manfred T. Brauch. Hard Sayings of the Bible. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1996.

- ^ Ramos, Alex. “Bar Kokhba.” In The Lexham Bible Dictionary, edited by John D. Barry, David Bomar, Derek R. Brown, Rachel Klippenstein, Douglas Mangum, Carrie Sinclair Wolcott, Lazarus Wentz, Elliot Ritzema, and Wendy Widder. Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016.

- ^ Tushmet L (1965). "Uncircumcision". Medical Times. 93 (6): 588–93. Archived from the original on 2013-10-23.[unreliable medical source?]

- ^ Collier R (December 2011). "Whole again: the practice of foreskin restoration". CMAJ. 183 (18): 2092–3. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-4009. PMC 3255154. PMID 22083672.

- ^ Cordes S, Calhoun KH, Quinn FB (1997-10-15). "Tissue Expanders". University of Texas Medical Branch Department of Otolaryngology Grand Rounds. Archived from the original on 2004-10-11.

- ^ Goodwin, Willard E. (1990-11-01). "Uncircumcision: A Technique for Plastic Reconstruction of a Prepuce after Circumcision". Journal of Urology. 144 (5): 1203–1205. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39693-3. PMID 2231896.

- ^ Greer Jr DM, Mohl PC, Sheley KA (2010). "A technique for foreskin reconstruction and some preliminary results". The Journal of Sex Research. 18 (4): 324–30. doi:10.1080/00224498209551158. JSTOR 3812166.

- ^ Griffith RW (1992). "Finishing Touches to the Foreskin". In Bigelow J (ed.). The Joy of Uncircumcising! (1998 ed.). Hourglass Book Pub. pp. 188–192. ISBN 0-9630482-1-X.

- ^ Brandes, S.B.; McAninch, J.W. (2002-05-27). "Surgical methods of restoring the prepuce: a critical review". BJU International. 83 (S1): 109–113. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1109.x. ISSN 1464-4096. PMID 10349422. S2CID 37867161.

- ^ Jefferson G (1916). "The peripenic muscle: some observations on the anatomy of phimosis". Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics. 23: 177–81.

- ^ Cold CJ, Taylor JR (January 1999). "The prepuce". BJU International. 83 (Suppl 1): 34–44. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1034.x. PMID 10349413. S2CID 30559310.

- ^ Taylor JR, Lockwood AP, Taylor AJ (February 1996). "The prepuce: specialized mucosa of the penis and its loss to circumcision". British Journal of Urology. 77 (2): 291–5. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.1996.85023.x. PMID 8800902.

- ^ Hammond T, Sardi LM, Jellison WA, McAllister R, Snyder B, Fahmy MAB (May 2023). "Foreskin restorers: insights into motivations, successes, challenges, and experiences with medical and mental health professionals – An abridged summary of key findings". International Journal of Impotence Research. 35 (3): 309–322. doi:10.1038/s41443-023-00686-5. PMID 36997741.

- ^ Bigelow J (Summer 1994). "Uncircumcising: undoing the effects of an ancient practice in a modern world". Mothering: 36–60.

- ^ Griffiths RW. "NORM - History". Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Qui sommes-nous?". Droit au Corps. 14 May 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Griffin GM (1992). Decircumcision: Foreskin Restoration, Methods and Circumcision Practices. Los Angeles: Added Dimensions Publishing. ISBN 1-879967-05-7.

- Bigelow J (1992). The Joy of Uncircumcising!: Exploring Circumcision: History, Myths, Psychology, Restoration, Sexual Pleasure, and Human Rights. Aptos, California: Hourglass Book Publishing. ISBN 0-9630482-1-X. (foreword by James L. Snyder)

- Payne RM, Fryer L (March 2001). "My responses to a few Frequently Asked Questions about Non-Surgical Foreskin Restoration" (PDF).

- Brandes SB, McAninch JW (January 1999). "Surgical methods of restoring the prepuce: a critical review". BJU International. 83 (Suppl. 1): 109–13. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1109.x. PMID 10349422. S2CID 37867161.[dead link]

- Schultheiss D, Truss MC, Stief CG, Jonas U (June 1998). "Uncircumcision: a historical review of preputial restoration". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 101 (7): 1990–8. doi:10.1097/00006534-199806000-00037. PMID 9623850.