Pan-Germanism

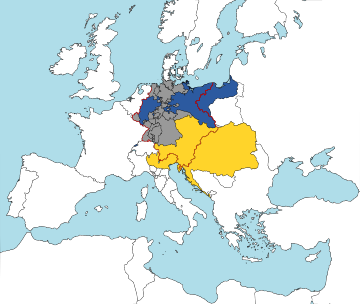

Pan-Germanism (German: Pangermanismus or Alldeutsche Bewegung), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also non-German Germanic-speaking peoples – in a single nation-state known as Greater Germany.

Pan-Germanism was highly influential in German politics in the 19th century during the unification of Germany when the German Empire was proclaimed as a nation-state in 1871 but without Habsburg Austria, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein (Kleindeutsche Lösung/Lesser Germany) and the first half of the 20th century in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the German Empire. From the late 19th century, many Pan-Germanist thinkers, since 1891 organized in the Pan-German League, had adopted openly ethnocentric and racist ideologies, and ultimately gave rise to the foreign policy Heim ins Reich pursued by Nazi Germany under Austrian-born Adolf Hitler from 1938, one of the primary factors leading to the outbreak of World War II.[1][2][3][4] The concept of a Greater Germany was attempted to be put into practice as the Greater Germanic Reich (German: Großgermanisches Reich), fully styled the Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation (German: Großgermanisches Reich der Deutschen Nation). As a result of the Second World War, there was a clear backlash against Pan-Germanism and other related ideologies. Today, pan-Germanism is mainly limited to a few nationalist groups, mainly on the political far right in Germany and Austria.

Etymology

[edit]The word pan is a Greek word element meaning "all, every, whole, all-inclusive". The word "German" in this context derives from Latin "Germani" originally used by Julius Caesar referring to tribes or a single tribe in northeastern Gaul. In the Late Middle Ages, it acquired a loose meaning referring to the speakers of Germanic languages some of whom spoke dialects ancestral to modern German. In English, "Pan-German" was first attested in 1892.

In German various concepts can be included under the heading of Pan-Germanism, though often with slight or significant differences in meaning. For example adjectives such as "alldeutsch" or "gesamtdeutsch", which can be translated as "pan-german", typically refer to the Alldeutsche Bewegung, a political movement which sought to unite all German speaking people in one country,[5] whereas "Pangermanismus" can refer to both the pursuit of uniting all the German-speaking people and movements which sought to unify all speakers of Germanic languages.[6]

Origins (before 1860)

[edit]

The origins of Pan-Germanism began with the birth of Romantic nationalism during the Napoleonic Wars, with Friedrich Ludwig Jahn and Ernst Moritz Arndt being early proponents. Germans, for the most part, had been a loose and disunited people since the Reformation, when the Holy Roman Empire was shattered into a patchwork of states following the end of the Thirty Years' War with the Peace of Westphalia.

Advocates of the Großdeutschland (Greater Germany) solution sought to unite all the German-speaking people in Europe, under the leadership of the German Austrians from the Austrian Empire. Pan-Germanism was widespread among the revolutionaries of 1848, notably among Richard Wagner and the Brothers Grimm.[3] Writers such as Friedrich List and Paul Anton Lagarde argued for German hegemony in Central and Eastern Europe, where German domination in some areas had begun as early as the 9th century AD with the Ostsiedlung, Germanic expansion into Slavic and Baltic lands. For the Pan-Germanists, this movement was seen as a Drang nach Osten, in which Germans would be naturally inclined to seek Lebensraum by moving eastwards to reunite with the German minorities there.

The Deutschlandlied ("Song of Germany"), written in 1841 by Hoffmann von Fallersleben, in its first stanza defines Deutschland as reaching "From the Meuse to the Memel / From the Adige to the Belt", i.e. as including East Prussia and South Tyrol.

Reflecting upon the First Schleswig War in 1848, Karl Marx noted in 1853 that "by quarrelling amongst themselves, instead of confederating, Germans and Scandinavians, both of them belonging to the same great race, only prepare the way for their hereditary enemy, the Slav."[7]

The German Question

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Germany |

|---|

|

There is, in political geography, no Germany proper to speak of. There are Kingdoms and Grand Duchies, and Duchies and Principalities, inhabited by Germans, and each separately ruled by an independent sovereign with all the machinery of State. Yet there is a natural undercurrent tending to a national feeling and toward a union of the Germans into one great nation, ruled by one common head as a national unit.

— The New York Times, 1 July 1866[8]

By the 1860s Prussia and Austria had become the two most powerful states dominated by German-speaking elites. Both sought to expand their influence and territory. The Austrian Empire—like the Holy Roman Empire—was a multi-ethnic state, but the German-speaking people there did not have an absolute numerical majority; its re-shaping into the Austro-Hungarian Empire was one result of the growing nationalism of other ethnicities—especially the Hungarians. Under Prussian leadership, Otto von Bismarck would ride on the coat-tails of nationalism to unite all of the northern German lands. After Bismarck excluded Austria and the German Austrians from Germany in the German war of 1866 and (following a few other events over the next few years), the unification of Germany, established the Prussian-dominated German Empire in 1871 with the proclamation of Wilhelm I as head of a union of German-speaking states, while disregarding millions of its non-German subjects who desired self-determination from German rule. After World War I the Pan-Germanist philosophy changed drastically during Adolf Hitler's rise to power. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking populations of Europe in a single nation-state known as Großdeutschland (Greater Germany), where "German-speaking" was sometimes taken as synonymous with Germanic-speaking, to the inclusion of the Frisian- and Dutch-speaking populations of the Low Countries, and Scandinavia.[9]

Although Bismarck had excluded Austria and the German Austrians from his creation of the Kleindeutschland state in 1871, integrating the German Austrians nevertheless remained a strong desire for many people of both Austria and Germany.[10] The most radical Austrian pan-German Georg Schönerer (1842–1921) and Karl Hermann Wolf (1862–1941) articulated Pan-Germanist sentiments in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[1] There was also a rejection of Roman Catholicism with the Away from Rome! movement (ca 1900 onwards) calling for German-speakers to identify with Lutheran or Old Catholic churches.[4] The Pan-German Movement gained an institutional format in 1891, when Ernst Hasse, a professor at the University of Leipzig and a member of the Reichstag, organized the Pan-German League, an ultra-nationalist[11] political-interest organization which promoted imperialism, antisemitism, and support for ethnic German minorities in other countries.[12] The organization achieved great support among the educated middle and upper class; it promoted German nationalist consciousness, especially among ethnic Germans outside Germany. In his three-volume work, "Deutsche Politik" (1905–07), Hasse called for German imperialist expansion in Europe. The Munich professor Karl Haushofer, Ewald Banse, and Hans Grimm (author of the novel Volk ohne Raum) preached similar expansionist policies.

During the German entry into World War I, Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg authorized the Septemberprogramm proposing that the German Empire use the First World War to seek territorial annexations similar to the ones demanded by pan-German nationalists. The West German historian Fritz Fischer argued in his 1962 thesis Germany's Aims in the First World War that this and other documents indicated that Germany was responsible for World War I and intended to fulfill pan-German aims, although other historians have since disputed this conclusion. After Naval Minister Alfred von Tirpitz resigned from the Cabinet under pressure from Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg over Tirpitz's push to introduce unrestricted submarine warfare,[13] Tirpitz united pan-German nationalists under the German Fatherland Party in the Reichstag.[14]

Austria

[edit]After the Revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas, in which the liberal nationalistic revolutionaries advocated the Greater German solution, the Austrian defeat in the Austro-Prussian War (1866) with the effect that Austria was now excluded from Germany, and increasing ethnic conflicts in the multinational Habsburg monarchy, a German national movement evolved in Austria.[15] Led by the radical German nationalist and Austrian antisemite Georg Ritter von Schönerer, organisations such as the Pan-German Society demanded the annexation of all German-speaking territories under the rule of the Habsburg monarchy to the German Empire, and fervently rejected Austrian nationalism and a pan-Austrian identity. Schönerer's völkisch and racist German nationalism was an inspiration to Adolf Hitler's Nazi ideology.[16]

In 1933, Austrian Nazis and the national-liberal Greater German People's Party formed an action group, fighting together against the Austrofascist Federal State of Austria which imposed a distinct Austrian national identity and in accordance said that Austrians were "better Germans." Kurt Schuschnigg adopted a policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany and called Austria the "better German state", but he still struggled to keep Austria independent.[17] With "Anschluss" of Austria in 1938, the historic aim of Austria's German nationalists was achieved.[18]

After the end of Nazi Germany and the events of World War II in 1945, the ideas of pan-Germanism and an Anschluss fell out of favour due to their association with Nazism and allowed Austrians to develop their own national identity. Nevertheless, such notions were revived with the German national camp in the Federation of Independents and the early Freedom Party of Austria.[19]

Scandinavia

[edit]The idea of including the North Germanic-speaking Scandinavians into a Pan-German state, sometimes referred to as Pan-Germanicism,[20] was promoted alongside mainstream pan-German ideas.[21] Jacob Grimm adopted Munch's anti-Danish Pan-Germanism and argued that the entire peninsula of Jutland had been populated by Germans before the arrival of the Danes and that thus it could justifiably be reclaimed by Germany, whereas the rest of Denmark should be incorporated into Sweden. This line of thinking was countered by Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, an archaeologist who had excavated parts of Danevirke, who argued that there was no way of knowing the language of the earliest inhabitants of Danish territory. He also pointed out that Germany had more solid historical claims to large parts of France and England, and that Slavs—by the same reasoning—could annex parts of Eastern Germany. Regardless of the strength of Worsaae's arguments, pan-Germanism spurred on the German nationalists of Schleswig and Holstein and led to the First Schleswig War in 1848. In turn, this likely contributed to the fact that Pan-Germanism never caught on in Denmark as much as it did in Norway.[22] Pan-Germanic tendencies were particularly widespread among the Norwegian independence movement. Prominent supporters included Peter Andreas Munch, Christopher Bruun, Knut Hamsun, Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson.[3][23][24] Bjørnson, who wrote the lyrics for the Norwegian national anthem, proclaimed in 1901:

I'm a Pan-Germanist, I'm a Teuton, and the greatest dream of my life is for the South Germanic peoples and the North Germanic peoples and their brothers in diaspora to unite in a fellow confederation.[3]

In the 20th century the German Nazi Party sought to create a Greater Germanic Reich that would include most of the Germanic peoples of Europe within it under the leadership of Germany, including peoples such as the Danes, the Dutch, the Swedes, the Norwegians, and the Flemish within it.[25]

Anti-German Scandinavism surged in Denmark in the 1930s and 1940s in response to the pan-Germanic ambitions of Nazi Germany.[26]

1918 to 1945

[edit]World War I became the first attempt to carry out the Pan-German ideology in practice, and the Pan-German movement argued forcefully for expansionist imperialism.[28]

Following the defeat in World War I, the influence of German-speaking elites over Central and Eastern Europe was greatly limited. At the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was substantially reduced in size. Alsace-Lorraine was also influenced by the Francization after it returned to France. Austria-Hungary was split up. A rump Austria, which to a certain extent corresponded to the German-speaking areas of Austria-Hungary (a complete split into language groups was impossible due to multi-lingual areas and language-exclaves) adopted the name "German Austria" (German: Deutschösterreich) in hope for union with Germany. Union with Germany and the name "German Austria" was forbidden by the Treaty of St. Germain and the name had to be changed back to Austria.

It was in the Weimar Republic that the Austrian-born Adolf Hitler, under the influence of the stab-in-the-back myth, first took up German nationalist ideas in his Mein Kampf.[28] Hitler met Heinrich Class in 1918, and Class provided Hitler with support for the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. Hitler and his supporters shared most of the basic pan-German visions with the Pan-German League, but differences in political style led the two groups to open rivalry. The German Workers Party of Bohemia cut its ties to the pan-German movement, which was seen as being too dominated by the upper classes, and joined forces with the German Workers' Party led by Anton Drexler, which later became the Nazi Party (National Socialist German Workers' Party, NSDAP) that was to be headed by Adolf Hitler from 1921.[29]

Nazi propaganda also used the political slogan Ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer ("One people, one Reich, one leader"), to enforce pan-German sentiment in Austria for an "Anschluss".

The chosen name for the projected empire was a deliberate reference to the Holy Roman Empire (of the German Nation) that existed in the Middle Ages, known as the First Reich in Nazi historiography.[30] Different aspects of the legacy of this medieval empire in German history were both celebrated and derided by the Nazi government. Hitler admired the Frankish Emperor Charlemagne for his "cultural creativity", his powers of organization, and his renunciation of the rights of the individual.[30] He criticized the Holy Roman Emperors however for not pursuing an Ostpolitik (Eastern Policy) resembling his own, while being politically focused exclusively on the south.[30] After the Anschluss, Hitler ordered the old imperial regalia (the Imperial Crown, Imperial Sword, the Holy Lance and other items) residing in Vienna to be transferred to Nuremberg, where they were kept between 1424 and 1796.[31] Nuremberg, in addition to being the former unofficial capital of the Holy Roman Empire, was also the place of the Nuremberg rallies. The transfer of the regalia was thus done to both legitimize Hitler's Germany as the successor of the "Old Reich", but also weaken Vienna, the former imperial residence.[32]

After the 1939 German occupation of Bohemia, Hitler declared that the Holy Roman Empire had been "resurrected", although he secretly maintained his own empire to be better than the old "Roman" one.[33] Unlike the "uncomfortably internationalist Catholic empire of Barbarossa", the Germanic Reich of the German Nation would be racist and nationalist.[33] Rather than a return to the values of the Middle Ages, its establishment was to be "a push forward to a new golden age, in which the best aspects of the past would be combined with modern racist and nationalist thinking".[33]

The historical borders of the Holy Roman Empire were also used as grounds for territorial revisionism by the NSDAP, laying claim to modern territories and states that were once part of it. Even before the war, Hitler had dreamed of reversing the Peace of Westphalia, which had given the territories of the Empire almost complete sovereignty.[34] On November 17, 1939, Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary that the "total liquidation" of this historic treaty was the "great goal" of the Nazi regime,[34] and that since it had been signed in Münster, it would also be officially repealed in the same city.[35]

| Part of a series on |

| Nazism |

|---|

|

The Heim ins Reich ("Back Home to the Reich") initiative was a policy pursued by the Nazis which attempted to convince the ethnic Germans living outside of Nazi Germany (such as in Austria and Sudetenland) that they should strive to bring these regions "home" into a Greater Germany. This notion also led the way for an even more expansive state to be envisioned, the Greater Germanic Reich, which Nazi Germany tried to establish.[36] This pan-Germanic empire was expected to assimilate practically all of Germanic Europe into an enormously expanded Greater Germanic Reich. Territorially speaking, this encompassed the already-enlarged Reich itself (consisting of pre-1938 Germany plus the areas annexed into the Großdeutsche Reich), the Netherlands, Belgium, areas in north-eastern France considered to be historically and ethnically Germanic, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Iceland, at least the German-speaking parts of Switzerland, and Liechtenstein.[37] The most notable exception was the predominantly Anglo-Saxon United Kingdom, which was not projected as having to be reduced to a German province but to instead become an allied seafaring partner of the Germans.[38]

The eastern Reichskommissariats in the vast stretches of Ukraine and Russia were also intended for future integration, with plans for them stretching to the Volga or even beyond the Urals. They were deemed of vital interest for the survival of the German nation, as it was a core tenet of Nazi ideology that it needed "living space" (Lebensraum), creating a "pull towards the East" (Drang nach Osten) where that could be found and colonized, in a model that the Nazis explicitly derived from the American Manifest Destiny in the Far West and its clearing of native inhabitants.

As the foreign volunteers of the Waffen-SS were increasingly of non-Germanic origin, especially after the Battle of Stalingrad, among the organization's leadership (e.g. Felix Steiner) the proposition for a Greater Germanic Empire gave way to a concept of a European union of self-governing states, unified by German hegemony and the common enemy of Bolshevism.[citation needed] The Waffen-SS was to be the eventual nucleus of a common European army where each state would be represented by a national contingent.[citation needed] Himmler himself, however, gave no concession to these views, and held on to his Pan-Germanic vision in a speech given in April 1943 to the officers of the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich and the 3rd SS Division Totenkopf:

We do not expect you to renounce your nation. [...] We do not expect you to become German out of opportunism. We do expect you to subordinate your national ideal to a greater racial and historical ideal, to the Germanic Reich.[39]

History since 1945

[edit]The defeat of Germany in World War II brought about the decline of Pan-Germanism, much as World War I had led to the demise of Pan-Slavism.[citation needed] Parts of Germany itself were devastated, and the country was divided, firstly into Soviet, French, American, and British zones and then into West Germany and East Germany. Austria was separated from Germany and the German identity in Austria was also weakened. The end of World War II in Europe brought even larger territorial losses for Germany than the First World War, with vast portions of eastern Germany directly annexed by the Soviet Union and Poland. The scale of the Germans' defeat was unprecedented; Pan-Germanism became taboo because it had been tied to racist concepts of the "master race" and Nordicism by the Nazi party. However, the reunification of Germany in 1990 revived the old debates.[40]

See also

[edit]|

18th century and before |

19th century

|

20th century

|

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ a b "Pan-Germanism (German political movement) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ Origins and Political Character of Nazi Ideology Hajo Holborn Political Science Quarterly Vol. 79, No. 4 (Dec. 1964), p.550

- ^ a b c d "Slik ble vi germanersvermere – magasinet". Dagbladet.no. 7 May 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ a b Mees, Bernard (2008). The Science of the Swastika. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-18-0.

- ^ Kruse, Wolfgang (27 September 2012). "Nation und Nationalismus". Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- ^ Toni Cetta; Georg Kreis: "Pangermanismus", in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version of 23.09.2010. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/017464/2010-09-23/, last seen 21.04.2023.

- ^ Marx, Karl (1994). The Eastern Question. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 90. ISBN 0-7146-1500-5.

- ^ "The Situation of Germany" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 July 1866. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Nationalism and Globalisation: Conflicting Or Complementary. D. Halikiopoulou. p51.

- ^ "Das politische System in Österreich (The Political System in Austria)" (PDF) (in German). Vienna: Austrian Federal Press Service. 2000. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ Eric J. Hobsbawm (1987). The age of empire, 1875–1914. Pantheon Books. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-394-56319-0. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ Drummond, Elizabeth A. (2005). "Pan-German League". In Levy, Richard S. (ed.). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. Contemporary world issues. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 528–529. ISBN 9781851094394. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ Epkenhans, Michael (15 March 2016). Daniel, Ute; Gatrell, Peter; Janz, Oliver; Jones, Heather; Keene, Jennifer; Kramer, Alan; Nasson, Bill (eds.). "Tirpitz, Alfred von". 1914-1918-Online International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.15463/ie1418.10860. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ Robson, Stuart (2007). The First World War. Internet Archive (1 ed.). Harrow, England: Pearson Longman. pp. 28–69. ISBN 978-1-4058-2471-2.

- ^ Bauer, Kurt (2008), Nationalsozialismus: Ursprünge, Anfänge, Aufstieg und Fall (in German), Böhlau Verlag, p. 41, ISBN 9783825230760

- ^ Wladika, Michael (2005), Hitlers Vätergeneration: Die Ursprünge des Nationalsozialismus in der k.u.k. Monarchie (in German), Böhlau Verlag, p. 157, ISBN 9783205773375

- ^ Morgan, Philip (2003). Fascism in Europe, 1919–1945. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 0-415-16942-9.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998), A history of eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, p. 355, ISBN 9780415161121

- ^ Pelinka, Anton (2000), "Jörg Haiders "Freiheitliche" – ein nicht nur österreichisches Problem", Liberalismus in Geschichte und Gegenwart (in German), Königshausen & Neumann, p. 233, ISBN 9783826015540

- ^ Thomas Pedersen. Germany, France, and the integration of Europe: a realist interpretation. Pinter, 1998. P. 74

- ^ Ian Adams. Political Ideology Today. Manchester, England, UK: Manchester University Press, 1993. P. 95.

- ^ Rowly-Conwy, Peter (2013). "The concept of prehistory and the invention of the terms 'prehistoric' and 'prehistorian': The Scandinavian origin, 1833–1850" (PDF). European Journal of Archaeology. 9 (1): 103–130. doi:10.1177/1461957107077709. S2CID 163132775.

- ^ NRK (20 January 2005). "Drømmen om Norge". NRK.no. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ Larson, Philip E. (1999). Ibsen in Skien and Grimstad: His education, reading, and early works (PDF). Skien: The Ibsen House and Grimstad Town Museum. p. 143.

- ^ Germany: The Long Road West: Volume 2: 1933–1990. Digital version. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- ^ Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael. Language and Nationalism in Europe. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 2000. P. 111.

- ^ "Utopia: The 'Greater Germanic Reich of the German Nation'". München – Berlin: Institut für Zeitgeschichte. 1999. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ a b World fascism: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1 Cyprian Blamires ABC-CLIO, 2006. pp. 499–501

- ^ Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1, Richard S. Levy, 529–530, ABC-CLIO 2005

- ^ a b c Hattstein 2006, p. 321.

- ^ Hamann, Brigitte (1999). Hitler's Vienna: A Dictator's Apprenticeship. Trans. Thomas Thornton. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512537-5.

- ^ Haman 1999, p. 110

- ^ a b c Brockmann 2006, p. 179.

- ^ a b Sager & Winkler 2007, p. 74.

- ^ Goebbels, p. 51.

- ^ Elvert 1999, p. 325.

- ^ Rich 1974, pp. 401–402.

- ^ Strobl 2000, pp. 202–208.

- ^ Stein 1984, p. 148.

- ^ Zeilinger, Gerhard (16 June 2011). "Straches "neue" Heimat und der Boulevardsozialismus". Der Standard (in German). Retrieved 28 June 2011.

Further reading

- Chickering, Roger. We Men Who Feel Most German: Cultural Study of the Pan-German League, 1886–1914. Harper Collins Publishers Ltd. 1984.

- Kleineberg, A.; Marx Chr.; Knobloch E.; Lelgemann D. Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios'"Atlas der Oikumene". WBG 2010. ISBN 978-3-534-23757-9.

- Jackisch, Barry Andrew. 'Not a Large, but a Strong Right': The Pan-German League, Radical Nationalism, and Rightist Party Politics in Weimar Germany, 1918–1939. Bell and Howell Information and Learning Company: Ann Arbor. 2000.

- Wertheimer, Mildred. The Pan-German League, 1890–1914. Columbia University Press: New York. 1924.