Gubbio

Gubbio | |

|---|---|

| Città di Gubbio | |

Panorama of Gubbio | |

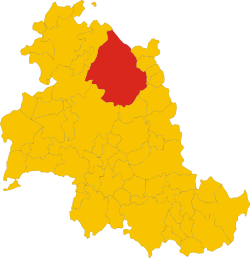

Gubbio within the Province of Perugia | |

| Coordinates: 43°21′13″N 12°34′25″E / 43.35361°N 12.57361°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Umbria |

| Province | Perugia (PG) |

| Frazioni | see list |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Filippo Mario Stirati (SEL) |

| Area | |

• Total | 525 km2 (203 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 522 m (1,713 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2010)[2] | |

• Total | 32,998 |

| • Density | 63/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Eugubini |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 06024, 06020 |

| Dialing code | 075 |

| Patron saint | St. Ubaldus |

| Saint day | 16 May |

| Website | Official website |

Gubbio (Italian pronunciation: [ˈɡubbjo]) is an Italian town and comune in the far northeastern part of the Italian province of Perugia (Umbria). It is located on the lowest slope of Mt. Ingino, a small mountain of the Apennines.

History

[edit]The city's origins are very ancient. The hills above the town were already occupied in the Bronze Age.[3] As Ikuvium, it was an important town of the Umbri in pre-Roman times, made famous for the discovery there in 1444 of the Iguvine Tablets,[4] a set of bronze tablets that together constitute the largest surviving text in the Umbrian language. After the Roman conquest in the 2nd century BC – it kept its name as Iguvium – the city remained important, as attested by its Roman theatre, the second-largest surviving in the world.

Gubbio became very powerful at the beginning of the Middle Ages. The town sent 1000 knights to fight in the First Crusade under the lead of Girolamo of the prominent Gabrielli family, who, according to an undocumented local tradition, were the first to reach the Church of the Holy Sepulchre when Jerusalem was seized (1099).

The following centuries in Gubbio were turbulent, featuring wars against the neighbouring towns of Umbria. One of these wars saw the miraculous intervention of its bishop, Ubald, who secured Gubbio an overwhelming victory (1151) and a period of prosperity. In the struggles of Guelphs and Ghibellines, the Gabrielli, such as the condottiero Cante dei Gabrielli (c. 1260–1335), fought for the Guelph faction, supporting the papacy. As Podestà of Florence, Cante exiled Dante Alighieri, ensuring his own lasting notoriety.

In 1350 Giovanni Gabrielli, count of Borgovalle seized power as the lord of Gubbio. His rule was short, and he was forced to hand over the town to Cardinal Gil Álvarez Carrillo de Albornoz, representing the Papal states (1354).

A few years later, Gabriello Gabrielli, the bishop of Gubbio, also proclaimed himself lord of Gubbio (Signor d'Agobbio). Betrayed by a group of noblemen which included many of his relatives, the bishop was forced to leave the town and seek refuge at his home castle at Cantiano.

With the decline of the political prestige of the Gabrielli, Gubbio was thereafter incorporated into the territories of the House of Montefeltro. The lord of Urbino, Federico da Montefeltro rebuilt the ancient Palazzo Ducale in Gubbio, incorporating in it a studiolo veneered with intarsia like his studiolo at Urbino.[5] The maiolica industry at Gubbio reached its apogee in the first half of the 16th century, with metallic lustre glazes imitating gold and copper.

Gubbio became part of the Papal States in 1631, when the della Rovere family, to whom the Duchy of Urbino had been granted, was extinguished. In 1860 Gubbio was incorporated into the Kingdom of Italy along with the rest of the Papal States.

The name of the Pamphili family, a great papal family, originated in Gubbio then went to Rome under the pontificate of Pope Innocent VIII (1484–1492), and is immortalized by Diego Velázquez and his portrait of Pope Innocent X.

Geography

[edit]

Overview

[edit]The town is located in northern Umbria, near the border with Marche. The municipality borders Cagli (PU), Cantiano (PU), Costacciaro, Fossato di Vico, Gualdo Tadino, Perugia, Pietralunga, Scheggia e Pascelupo, Sigillo, Umbertide and Valfabbrica.[6]

Frazioni

[edit]The frazioni (territorial subdivisions) of the comune of Gubbio are the villages of: Belvedere, Bevelle, Biscina, Branca, Burano, Camporeggiano, Carbonesca, Casamorcia-Raggio, Cipolleto, Colonnata, Colpalombo, Ferratelle, Loreto, Magrano, Mocaiana, Monteleto, Monteluiano, Nogna, Padule, Petroia, Ponte d'Assi, Raggio, San Benedetto Vecchio, San Marco, San Martino in Colle, Santa Cristina, Scritto, Semonte, Spada, Torre Calzolari and Villa Magna.

Monuments and sites of interest

[edit]

The historical centre of Gubbio has a decidedly medieval aspect: the town is austere in appearance because of the dark grey stone, narrow streets, and Gothic architecture. Many houses in central Gubbio date to the 14th and 15th centuries, and were originally the dwellings of wealthy merchants. They often have a second door fronting on the street, usually just a few centimetres from the main entrance. This secondary entrance is narrower, and 30 centimetres (1 ft) or so above the actual street level. This type of door is called a porta dei morti (door of the dead) because it was proposed that they were used to remove the bodies of any who might have died inside the house. This is almost certainly false, but there is no agreement as to the purpose of the secondary doors. A more likely theory is that the door was used by the owners to protect themselves when opening to unknown persons, leaving them in a dominating position.

Religious architecture or sites

[edit]- Duomo: This cathedral was built in the late 12th century. The most striking feature is the rose-window in the façade with, at its sides, the symbols of the Evangelists: the eagle for John the Evangelist, the lion for Mark the Evangelist, the angel for Matthew the Apostle and the ox for Luke the Evangelist. The interior has a latine cross plan with a single nave. The most precious art piece is the wooden Christ over the altar, of the Umbrian school.

- San Francesco: This church from the second half of the 13th century is the sole religious edifice in the city having a nave with two aisles. The vaults are supported by octagonal pilasters. The frescoes on the left side date from the 15th century.

- Santa Maria Nuova: This is a typical Cistercian church of the 13th century. In the interior is a 14th-century fresco portraying the so-called Madonna del Belvedere (1413), by Ottaviano Nelli. It also has a work by Guido Palmeruccio. Also from the Cistercians is the Convent of St. Augustine, with some frescoes by Nelli.

- Basilica of Sant'Ubaldo, with a nave and four aisles is a sanctuary outside the city. Noteworthy are the marble altar and the great windows with episodes of the life of Ubald, patron of Gubbio. The finely sculpted portals and the fragmentary frescoes give a hint of the magnificent 15th-century decoration once boasted by the basilica.

- San Giovanni Battista, Gubbio: 13th-century church with one nave only with four transversal arches supporting the pitched roof, a model for later Gubbio churches.

- San Domenico, once known as San Martino

- Sant'Agostino

- Santa Croce della Foce

Secular architecture or sites

[edit]- Roman Theatre: This ancient open air theater built in the 1st century BC using square blocks of local limestone. Traces of mosaic decoration have been found. Originally, the diameter of the cavea was 70 metres and could house up to 6,000 spectators.

- Roman Mausoleum: This Mausoleum is sometimes said to be of Gaius Pomponius Graecinus, but on no satisfactory grounds.

- Palazzo dei Consoli: Dating to the first half of the 14th century, this massive palace, is now a museum housing the Iguvine Tablets.

- Palazzo and Torre Gabrielli

- Palazzo Ducale: The Palace built from 1470 by Luciano Laurana or Francesco di Giorgio Martini for Federico da Montefeltro. Famous is the inner court, reminiscent of the Palazzo Ducale, Urbino.

- Museo Cante Gabrielli: This museum is housed in the Palazzo del Capitano del Popolo, which once belonged to the Gabrielli family.

- Vivian Gabriel Oriental Collection: This is a museum of Tibetan, Nepalese, Chinese and Indian art. The collection was donated to the municipality by Edmund Vivian Gabriel (1875–1950), British colonial officer and adventurer, a collateral descendant of the Gabrielli who were lords of Gubbio in the Middle Ages.

Culture

[edit]

Gubbio is home to the Corsa dei Ceri, a run held every year always on Saint Ubaldo Day, the 15th day of May, in which three teams, devoted to Ubald, Saint George and Saint Anthony the Great run through throngs of cheering supporters clad in the distinctive colours of yellow, blue and black, with white trousers and red belts and neckbands, up much of the mountain from the main square in front of the Palazzo dei Consoli to the basilica of St. Ubaldo, each team carrying a statue of their saint mounted on a wooden octagonal prism, similar to an hour-glass shape 4 metres (13 ft) tall and weighing about 280 kg (617 lb).

The race has strong devotional, civic, and historical overtones and is one of the best-known folklore manifestations in Italy; the Ceri was chosen as the heraldic emblem on the coat of arms of Umbria as a modern administrative region.

A celebration like the Corsa dei Ceri is held also in Jessup, Pennsylvania. In this small town the people carry out the same festivities as the residents of Gubbio do by "racing" the three statues through the streets during the Memorial Day weekend. This remains an important and sacred event in both towns.

Gubbio was also one of the centres of production of the Italian pottery (maiolica), during the Renaissance. The most important Italian potter of that period, Giorgio Andreoli, was active in Gubbio during the early 16th century.

The town's most famous story is that of "The Wolf of Gubbio"; a man-eating wolf that was tamed by St. Francis of Assisi and who then became a docile resident of the city. The legend is related to the 14th-century Little Flowers of St. Francis.

The Gubbio Layer

[edit]Gubbio is also known among geologists and palaeontologists as the discovery place of what was at first called the "Gubbio layer", a sedimentary layer enriched in iridium that was exposed by a roadcut outside of town. This thin, dark band of sediment marks the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary, also known as the K–T boundary or K–Pg boundary, between the Cretaceous and Paleogene geological periods about 66 million years ago, and was formed by infalling debris from the gigantic meteor impact probably responsible for the mass extinction of the dinosaurs. Its iridium, a heavy metal rare on Earth's surface, is plentiful in extraterrestrial material such as comets and asteroids. It also contains small globules of glassy material called tektites, formed in the initial impact. Discovered at Gubbio, the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary is also visible at many places all over the world. The characteristics of this boundary layer support the theory that a devastating meteorite impact, with accompanying ecological and climatic disturbance, was directly responsible for the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event.

Gubbio in fiction

[edit]In Hermann Hesse's novel Steppenwolf (1927) the isolated and tormented protagonist – a namesake of the wolf – consoles himself at one point by recalling a scene that the author might have beheld during his travels: "(...) that slender cypress on the hill over Gubbio that, though split and riven by a fall of stone, yet held fast to life and put forth with its last resources a new sparse tuft at the top".[7]

The town is a backdrop in Antal Szerb's novel Journey by Moonlight (1937) as well as Danièle Sallenave's Les Portes de Gubbio (1980).

The TV series Don Matteo, where the title character ministers to his parish while solving crimes, was shot on location in Gubbio between 2000 and 2011.

The 2024 novel What We Buried by Robert Rotenberg takes place in Canada and Gubbio. In particular, the novel involves the 40 "Martyrs of Gubbio", civilians seized from their homes by German soldiers late in WW2 and shot, in reprisal for the shooting of a German officer by partisans.

Other

[edit]Anna Moroni, a popular cook on the Italian daytime TV series "La Prova del Cuoco" discusses Gubbio in many of her TV segments. She often cooks dishes from the region on TV, and she featured Gubbio in her first book.

Sport

[edit]A.S. Gubbio 1910 football club play in Serie C at the Pietro Barbetti Stadium.

Transportation

[edit]The city is served by Fossato di Vico–Gubbio railway station located in Fossato di Vico; until 1945 it also operated the Central Apennine railway (Ferrovia Appenino Centrale abbreviation FAC) with a narrow gauge which departed from Arezzo and reached as far as Fossato di Vico and in Gubbio had his own railway station located in via Beniamino Ubaldi 2, now completely demolished.

International relations

[edit]Twin towns – Sister cities

[edit]Gubbio is twinned with:

|

Notable people

[edit]- Giosuè Fioriti (born 1989), Italian footballer

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Italian National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ^ Population data from Istat

- ^ Malone, C. A. T.; Stoddart, S. K. F. (1994). Territory, Time and State. The archaeological development of the Gubbio basin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Poultney, J. W. Bronze Tables of Iguvium 1959

- ^ The Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio is reassembled in its entirety at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Federico's father, Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, and his daughter Agnese di Montefeltro were born in Gubbio.

- ^ 42390 Gubbio on OpenStreetMap

- ^ Herman Hesse, Steppenwolf, chapter 1. ("For Madmen Only")

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Official site of the Festa dei Ceri

- Gubbio at Associazione Eugubini nel Mondo website

- Thayer's Gazetteer

- Rugby Gubbio - Official Web Site

- Paradoxplace Gubbio Photo Pages

- Sbandieratori di Gubbio (flag-wavers, flag-throwers)

- Harris, W., R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies (13 July 2020). "Places: 413174 (Iguvium)". Pleiades. Retrieved 7 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - The Gubbio Studiolo and its conservation, volumes 1 & 2, from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gubbio (see index)

- Period Rooms in the Metropolitan Museum of Art , from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Gubbio (see index)