History of trams

| Part of a series on |

| Rail transport |

|---|

|

|

|

| Infrastructure |

|

|

| Service and rolling stock |

|

| Urban rail transit |

|

|

| Miscellanea |

|

|

The history of trams, streetcars, or trolleys began in the early nineteenth century. It can be divided up into several discrete periods defined by the principal means of motive power used.[2] Eventually the so-called US "street railways" were deemed advantageous auxiliaries of the new elevated and/or tunneled metropolitan steam railways.[3][4]

Horse-drawn

[edit]

The world's first passenger tram was the Swansea and Mumbles Railway, in Wales, UK. The Mumbles Railway Act was passed by the British Parliament in 1804, and this first horse-drawn passenger tramway started operating in 1807.[5] It was worked by steam from 1877, and then, from 1929, by very large (106-seater) electric tramcars, until closure in 1961.

The first streetcar in America, developed by John Stephenson, began service in the year 1832.[6] This was the New York and Harlem Railroad's Fourth Avenue Line which ran along the Bowery and Fourth Avenue in New York City. These trams were an animal railway, usually using horses and sometimes mules to haul the cars, usually two as a team. Rarely, other animals were tried, including humans in emergency circumstances. It was followed in 1835 by New Orleans, Louisiana, which is the oldest continuously operating street railway system in the world, according to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.[7]

The first tram in Continental Europe opened in France in 1839 between Montbrison and Montrond, on the streets inside the towns, and on the roadside outside town. It had permission for steam traction but was entirely run with horse traction. In 1848, it was closed down after repeated economic failure. The tram developed in numerous cities of Europe (some of the most extensive systems were found in Berlin, Budapest, Birmingham, Leningrad, Lisbon, London, Manchester, Paris).

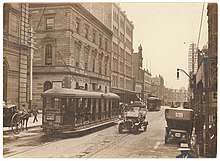

The first tram in South America opened on 10 June 1858 in Santiago, Chile. The first trams in Australia opened in 1860 in Sydney. Africa's first tram service started in Alexandria on 8 January 1863. The first trams in Asia opened in 1869 in Batavia (now Jakarta), Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia).

Problems with horsecars included the fact that any given animal could only work so many hours on a given day, had to be housed, groomed, fed and cared for day in and day out, and produced prodigious amounts of manure, which the streetcar company was charged with storing and then disposing of. Since a typical horse pulled a streetcar for about a dozen miles a day and worked for four or five hours, many systems needed ten or more horses in stable for each horse car.

Beginning in the late 19th century, horse cars were largely replaced by electric-powered trams. Several inventors and companies were involved in the transition. Werner von Siemens pioneered electric traction in the early 1880s in Berlin. In the US, Frank J. Sprague's groundbreaking work collecting power from overhead wires using trolleys kickstarted the transition. His spring-loaded trolley pole used a wheel to travel along the wire. In late 1887 and early 1888, using his trolley system, Sprague installed the first successful large electric street railway system in Richmond, Virginia. Within a year, the economy of electric power had replaced more costly horse cars in many cities. By 1889, 110 electric railways incorporating Sprague's equipment had been begun or planned on several continents.[8]

Horses continued to be used for light shunting well into the 20th century. New York City had a regular horse car service on the Bleecker Street Line until its closure in 1917.[9] Pittsburgh, had its Sarah Street line drawn by horses until 1923. The last regular mule-drawn cars in the US ran in Sulphur Rock, Arkansas, until 1926 and were commemorated by a U.S. postage stamp issued in 1983.[10] The last mule tram service in Mexico City ended in 1932, and a mule tram in Celaya, Mexico, survived until 1954.[11] The last horse-drawn tram to be withdrawn from public service in the UK took passengers from Fintona railway station to Fintona Junction one mile away on the main Omagh to Enniskillen railway in Northern Ireland. The tram made its last journey on 30 September 1957 when the Omagh to Enniskillen line closed. The van now lies at the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum.

Horse-drawn trams still operate on the 1876-built Douglas Bay Horse Tramway on the Isle of Man, and on the 1894-built Victor Harbor Horse Drawn Tram, in Adelaide, South Australia. New horse-drawn systems have been established at the Hokkaidō Museum in Japan and in Disneyland.

Steam

[edit]High-pressure steam engine

[edit]The advantages of high-pressure engines were:

- They could be made much smaller than previously for a given power output. There was thus the potential for steam engines to be developed that were small and powerful enough to propel themselves and other objects. As a result, steam power for transportation now became a practicality in the form of ships and land vehicles, which revolutionized cargo businesses, travel, military strategy, and essentially every aspect of society.

- Because of their smaller size, they were much less expensive.

- They did not require the significant quantities of condenser cooling water needed by atmospheric engines.

- They could be designed to run at higher speeds, making them more suitable for powering machinery.

The disadvantages were:

- In the low-pressure range they were less efficient than condensing engines, especially if steam was not used expansively.

- They were more susceptible to boiler explosions.The main difference between how high-pressure and low-pressure steam engines work is the source of the force that moves the piston. In a high-pressure engine, most of the pressure difference is provided by the high-pressure steam from the boiler.

A number of municipal and company-owned street tramways were built or extended with the application of cognate technology related to high pressure steam innovations.

Cognate technology

[edit]

- Traction engines in steam vehicles

- Reduced mass steam motors and launch-type boilers in:

- Towed pump engines for firefighting

- Marine engines for a larger ship's carried-boats, canal boats, small watercraft work-boats.

- Lighter railmotors in general

- Railcars (UK) or Motorcars (US)

- Minimum-gauge railway

- Light railway – properly distinct from a tramway which operates under differing rules and may share a road.

Tram engine

[edit]The tram engine was a product of technical innovations with a convergence of increased demand for public transportation systems.

Tram engines usually had modifications to make them suitable for street running in residential areas.[12] The wheels, and other moving parts of the machinery, were usually enclosed for safety reasons and to make the engines quieter. Measures were often taken to prevent the engines from emitting visible smoke or steam. Usually, the engines used coke rather than coal as fuel to avoid emitting smoke; condensers or superheating were used to avoid emitting visible steam. A major drawback of this style of the tram was the limited space for the engine so that these trams had to replenish fuel and water more frequently compared to other locomotives.

Tram engines began to be used after popular promotion by George Francis Train of the United States, so called, "Street Railway" car companies using successful citywide horse-drawn railway transportation systems[13] and passage of Tramways Act 1870 (33 & 34 Vict. c. 78).

The first mechanical trams were powered by steam. Generally, there were two types of steam tram.[14]

- Detached Engine

- Combined Engine and Car

The first and most common had a small steam locomotive (called a tram engine in the UK or Steam dummy in the US) at the head of a line of one or more carriages, similar to a small train. Systems with such steam trams included Christchurch, New Zealand; Adelaide, South Australia; Sydney, Australia and other city systems in New South Wales; Munich, Germany (from August 1883 on),[15] British India (Pakistan) (from 1885), The Hague, Netherlands, 1878,[16] and the Dublin & Blessington Steam Tramway (from 1888) in Ireland. Steam tramways also were used on the suburban tramway lines around Milan and Padua; the last Gamba de Legn ("Peg-Leg") tramway ran on the Milan-Magenta-Castano Primo route in late 1958.[citation needed]

The other style of steam tram had the steam engine in the body of the tram, referred to as a steam tramway car.[17] The most notable system to adopt such trams was in Paris. French-designed steam trams also operated in Rockhampton, in the Australian state of Queensland between 1909 and 1939. Stockholm, Sweden, had a steam tram line at the island of Södermalm between 1887 and 1901.

Cable-hauled

[edit]

Another motive system for trams was the cable car, which was pulled along a fixed track by a moving steel cable. The power to move the cable was normally provided at a "powerhouse" site some distance away from the actual vehicle.

The London and Blackwall Railway, which opened for passengers in East London, England, in 1840 used such a system.[18]

The first practical cable car line was tested in San Francisco, in 1873. Part of its success is attributed to the development of an effective and reliable cable grip mechanism, to grab and release the moving cable without damage. The second city to operate cable trams was Dunedin in New Zealand, from 1881 to 1957.

The most extensive cable system in the US was built in Chicago between 1882 and 1906.[19][when?] New York City developed at least seven cable car lines.[when?] Los Angeles also had several cable car lines, including the Second Street Cable Railroad, which operated from 1885 to 1889, and the Temple Street Cable Railway, which operated from 1886 to 1898.

From 1885 to 1940, the city of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia operated one of the largest cable systems in the world, at its peak running 592 trams on 75 kilometres (47 mi) of track, though during its heyday, Sydney's network was larger,[20] with about 1,600 cars in service at any one time at its peak during the 1930s (cf. about 500 trams in Melbourne today). There were also two isolated cable lines in Sydney, the North Sydney line from 1886 to 1900,[21] and the King Street line from 1892 to 1905. Sydney's tram network ceased to serve the city population by the 1960s, with all tracks being removed, in lieu of a bus service. Melbourne's tram network, however, continues to run to this day.

In Dresden, Germany, in 1901 an elevated suspended cable car following the Eugen Langen one-railed floating tram system started operating. Cable cars operated on Highgate Hill in North London,[when?] and Kennington to Brixton Hill in South London (1891–1905).[22] They also worked around "Upper Douglas" in the Isle of Man from 1897 to 1929 (cable car 72/73 is the sole survivor of the fleet).

Cable cars suffered from high infrastructure costs, since an expensive system of cables, pulleys, stationary engines and lengthy underground vault structures beneath the rails had to be provided. They also required physical strength and skill to operate, and alert operators to avoid obstructions and other cable cars. The cable had to be disconnected ("dropped") at designated locations to allow the cars to coast by inertia, for example when crossing another cable line. The cable would then have to be "picked up" to resume progress, the whole operation requiring precise timing to avoid damage to the cable and the grip mechanism. Breaks and frays in the cable, which occurred frequently, required the complete cessation of services over a cable route while the cable was repaired. Due to overall wear, the entire length of cable (typically several kilometres) would have to be replaced on a regular schedule. After the development of reliable electrically powered trams, the costly high-maintenance cable car systems were rapidly replaced in most locations.

Cable cars remained especially effective in hilly cities since their non-driven wheels would not lose traction as they climbed or descended a steep hill. The moving cable would physically pull the car up the hill at a steady pace, unlike a low-powered steam or horse-drawn car. Cable cars do have wheel brakes and track brakes, but the cable also restrains the car so that it goes downhill at a constant speed (9 mph in San Francisco). Performance in steep terrain partially explains the survival of cable cars in San Francisco.

The San Francisco cable cars, though significantly reduced in number, continue to perform a regular transportation function, in addition to being a well-known tourist attraction. A single cable line also survives in Wellington, New Zealand (rebuilt in 1979 as a funicular but still called the Wellington Cable Car). Another system, actually two separate cable lines with a shared power station in the middle, operates from the Welsh town of Llandudno up to the top of the Great Orme hill in North Wales, UK.

Gas

[edit]In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a number of systems in various parts of the world employed trams powered by gas, naphtha gas or coal gas in particular. Gas trams are known to have operated between Alphington and Clifton Hill in the northern suburbs of Melbourne, Australia (1886–1888); in Berlin and Dresden, Germany; between Jelenia Góra, Cieplice, and Sobieszów in Poland (from 1897); and in the UK at Lytham St Annes, Neath (1896–1920), and Trafford Park, Manchester (1897–1908).

On 29 December 1886 the Melbourne newspaper The Argus reprinted a report from the San Francisco Bulletin that Mr Noble had demonstrated a new 'motor car' for tramways 'with success'. The tramcar 'exactly similar in size, shape, and capacity to a cable grip car' had the 'motive power' of gas 'with which the reservoir is to be charged once a day at power stations by means of a rubber hose'. The car also carried an electricity generator for 'lighting up the tram and also for driving the engine on steep grades and effecting a start'.[23]

Comparatively little has been published about gas trams. However, research on the subject was carried out for an article in the October 2011 edition of "The Times", the historical journal of the Australian Association of Timetable Collectors, now the Australian Timetable Association.[24][25][26][27]

A tram system powered by compressed natural gas was due to open in Malaysia in 2012,[28] but the news about the project appears to have dried up.

Electric

[edit]

The world's first experimental electric tramway was built by Russian born inventor Fyodor Pirotsky near St Petersburg, Russian Empire, in 1875. The first commercially successful electric tram line operated in Lichterfelde near Berlin, Germany, in 1881. It was built by Werner von Siemens (see Berlin Straßenbahn). It initially drew current from the rails, with the overhead wire being installed in 1883.[29]

In Britain, Leeds introduced Europe's first overhead electric service (Roundhay Electric Tramway) on 29 October 1891, though strictly speaking, it did not officially open to passengers until the following month.[30] The Volk's Electric Railway was opened in 1883 in Brighton. This two kilometer line, re-gauged to 2 feet 9 inches (840 mm) in 1884, remains in service to this day, and is the oldest operating electric tramway in the world. Also in 1883, Mödling and Hinterbrühl Tram was opened near Vienna in Austria. It was the first tram in the world in regular service that was run with electricity served by an overhead line with pantograph current collectors. The Blackpool Tramway, was opened in Blackpool, England on 29 September 1885 using conduit collection along Blackpool Promenade. This system is still in operation in a modernised form.

The earliest tram system in Canada was by John Joseph Wright, brother of the famous mining entrepreneur Whitaker Wright, in Toronto in 1883. In the US, multiple functioning experimental electric trams were exhibited at the 1884 World Cotton Centennial World's Fair in New Orleans, Louisiana, but they were not deemed good enough to replace the Lamm fireless engines then propelling the St Charles Streetcar in that city. The first commercial installation of an electric streetcar in the United States was built in 1884 in Cleveland, Ohio and operated for a period of one year by the East Cleveland Street Railway Company.[31] Trams were operated in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888, on the Richmond Union Passenger Railway built by Frank J. Sprague. Sprague later developed multiple unit control, first demonstrated in Chicago in 1897, allowing multiple cars to be coupled together and operated by a single motorman. This gave birth to the modern subway train.

Earlier electric installations often proved difficult or unreliable. The Lichterfelde line, for example, provided power through a live rail and a return rail, like a model train, limiting the voltage that could be used, and providing electric shocks to people and animals crossing the tracks.[32] The system for collecting electricity from the overhead wires was soon improved, however, through Frank J. Sprague's trolley pole and Werner von Siemens' bow collector. With new, reliable technology available, electric tram systems were rapidly adopted across the world.

Sidney Howe Short designed and produced the first electric motor that operated a streetcar without gears. The motor had its armature direct-connected to the streetcar's axle for the driving force.[33][34][35][36][37] Short pioneered "use of a conduit system of concealed feed" thereby eliminating the necessity of overhead wire, trolley poles and a trolley for street cars and railways.[38][33][34] While at the University of Denver he conducted important experiments which established that multiple unit powered cars were a better way to operate trains and trolleys.[33][34]

Sarajevo built a citywide system of electric trams in 1885.[39] Budapest established its tramway system in 1887, and its ring line has grown to be the busiest tram line in Europe, with a tram running every 60 seconds at rush hour. Bucharest and Belgrade[40] ran a regular service from 1894.[41][42] Ljubljana introduced its tram system in 1901 – it closed in 1958.[43]

The first electric tramway in Australia was a Sprague system demonstrated at the 1888 Melbourne Centennial Exhibition in Melbourne; afterwards, this was installed as a commercial venture operating between the outer Melbourne suburbs of Box Hill and Doncaster from 1889 to 1896.[44] As well, electric systems were built in Adelaide, Ballarat, Bendigo, Brisbane, Fremantle, Geelong, Hobart, Kalgoorlie, Launceston, Leonora, Newcastle, Perth and Sydney. By the 1970s, the only tramway system remaining in Australia was the Melbourne tram system other than a few single lines remaining elsewhere: the Glenelg tram line, connecting Adelaide to the beachside suburb of Glenelg, and tourist trams in the Victorian Goldfields cities of Ballarat and Bendigo. In recent years the Melbourne system, generally recognised as one of the largest in the world, has been considerably modernised and expanded. The Adelaide line has also been extended to the Entertainment Centre, and there are plans to expand further.

In Japan, the Kyoto Electric railroad was the first tram system, starting operation in 1895.[45] By 1932, the network had grown to 82 railway companies in 65 cities, with a total network length of 1,479 km (919 mi).[46] By the 1960s the tram had generally died out in Japan.

Two rare but significant alternatives were conduit current collection, which was widely used in London, Washington, D.C. and New York City, and the surface contact collection method, used in Wolverhampton (the Lorain system), Torquay and Hastings in the UK (the Dolter stud system), and currently in Bordeaux, France (the ground-level power supply system).

The convenience and economy of electricity resulted in its rapid adoption once the technical problems of production and transmission of electricity were solved. Electric trams largely replaced animal power and other forms of motive power including cable and steam, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

There is one particular hazard associated with trams powered from a trolley off an overhead line. Since the tram relies on contact with the rails for the current return path, a problem arises if the tram is derailed or (more usually) if it halts on a section of track that has been particularly heavily sanded by a previous tram, and the tram loses electrical contact with the rails. In this event, the underframe of the tram, by virtue of a circuit path through ancillary loads (such as saloon lighting), is live at the full supply voltage, typically 600 volts. In British terminology, such a tram was said to be 'grounded'—not to be confused with the US English use of the term, which means the exact opposite. Any person stepping off the tram completed the earth return circuit and could receive a nasty electric shock. In such an event the driver was required to jump off the tram (avoiding simultaneous contact with the tram and the ground) and pull down the trolley before allowing passengers off the tram. Unless derailed, the tram could usually be recovered by running water down the running rails from a point higher than the tram. The water providing a conducting bridge between the tram and the rails.

In the 2000s, two companies introduced catenary-free designs. The Alstom Citadis line uses a third rail, and Bombardier's Primove LRV is charged by contactless induction plates embedded in the trackway.[47]

Battery

[edit]As early as 1834, Thomas Davenport, a Vermont blacksmith, had invented a battery-powered electric motor which he later patented. The following year he used it to operate a small model electric car on a short section of track four feet in diameter.[48][49]

Attempts to use batteries as a source of electricity were made from the 1880s and 1890s, with unsuccessful trials conducted in among other places Bendigo and Adelaide in Australia, and for about 14 years as The Hague accutram of HTM in the Netherlands. The first trams in Bendigo, Australia, in 1892, were battery-powered but within as little as three months they were replaced with horse-drawn trams. In New York City some minor lines also used storage batteries. Then, comparatively recently, during the 1950s, a longer battery-operated tramway line ran from Milan to Bergamo. In China there is a Nanjing battery Tram line and has been running since 2014.[50]

Other power sources

[edit]

In some places, other forms of power were used to power the tram.

Hastings and some other tramways, for example Stockholms Spårvägar in Sweden and some lines in Karachi, used petrol trams. Paris operated trams that were powered by compressed air using the Mekarski system.

Galveston Island Trolley in Texas operated diesel trams due to the city's hurricane-prone location, which would result in frequent damage to an electrical supply system. Although Portland, Victoria promotes its tourist tram[51] as being a cable car it actually operates using a hidden diesel motor. The tram, which runs on a circular route around the town of Portland, uses dummies and salons formerly used on the extensive Melbourne cable tramway system and now beautifully restored.

In March 2015, China South Rail Corporation (CSR) demonstrated the world's first hydrogen fuel cell vehicle tramcar at an assembly facility in Qingdao. The chief engineer of the CSR subsidiary CRRC Qingdao Sifang, Liang Jianying, said that the company is studying how to reduce the running costs of the tram.[52][53]

Hybrid systems

[edit]

The Trieste–Opicina tramway in Trieste operates a hybrid funicular tramway system. Conventional electric trams are operated in street running and on reserved track for most of their route. However, on one steep segment of track, they are assisted by cable tractors, which push the trams uphill and act as brakes for the downhill run. For safety, the cable tractors are always deployed on the downhill side of the tram vehicle.

Similar systems were used elsewhere in the past, notably on the Queen Anne Counterbalance in Seattle and the Darling Street wharf line in Sydney.

Rail profile

[edit]At first the rails protruded above street level, causing accidents and problems for pedestrians. They were supplanted in 1852 by grooved rails or girder rails, invented by Alphonse Loubat.[54] Loubat, inspired by Stephenson, built the first tramline in Paris, France. The 2 km (1.2 mi) line was inaugurated on 21 November 1853, in connection with the 1855 World Fair, running on a trial basis from Place de la Concorde to Pont de Sèvres and later to the village of Boulogne.[55]

The Toronto streetcar system is one of the few in North America still operating in the classic style on street trackage shared with car traffic, where streetcars stop on demand at frequent stops like buses rather than having fixed stations. Known as Red Rockets because of their colour, they have been operating since the mid-19th century – horsecar service started in 1856 and electric service in 1892.[56]

Decline

[edit]

The advent of personal motor vehicles and the improvements in motorized buses caused the rapid disappearance of the tram from most western and Asian countries by the end of the 1950s (for example the first major UK city to completely abandon its trams was Manchester by January 1949). Continuing technical and reliability improvements in buses made them a serious competitor to trams because they did not require the construction of costly infrastructure.[57] However, the demise of the streetcar came when lines were torn out of the major cities by "bus manufacturing or oil marketing companies for the specific purpose of replacing rail service with buses."[58]

In many cases, postwar buses were cited as providing a smoother ride and a faster journey than the older, pre-war trams. For example, the tram network survived in Budapest but for a considerable period of time bus fares were higher to recognize the superior quality of the buses. However, many riders protested against the replacement of streetcars arguing that buses weren't as smooth or efficient and polluted the air. In the United States, there have been allegations that the Great American streetcar scandal was responsible for the replacement of trains with buses, but critics of this theory point to evidence that larger economic forces were driving conversion before General Motors' actions and outside of its reach. Certainly, the oldest system of all, the Swansea and Mumbles Railway of 1807, was purchased by The South Wales Transport Company (which operated a large motorbus fleet in the area) and despite vociferous local opposition, closed down in 1960.

Governments thus put investment principally into bus networks. Indeed, infrastructure for roads and highways meant for the automobile were perceived as a mark of progress. The priority given to roads is illustrated in the proposal of French president Georges Pompidou who declared in 1971 that "the city must adapt to the car". Tram networks were no longer maintained or modernized, a state of affairs that served to discredit them in the eyes of the public. Old lines, considered archaic, were then gradually replaced by buses.

Tram networks disappeared almost completely from France, the UK, and altogether from Ireland, Denmark, Spain, as well as being completely removed from cities such as Sydney, which had one of the largest networks in the world with route length 291 km (181 mi) and Brisbane. The vast majority of tram networks also disappeared in North America, but American cities Boston, Philadelphia, Newark, San Francisco, New Orleans, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Canadian city Toronto, and Mexico City still retained trams. This situation occurred in Italy and Netherlands, too. There are preserved system in Milan, Rome, Naples, Turin, Ritten and between Trieste and Opicina, and in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague. On the other hand, tram systems were generally retained or modernized in most communist countries, as well as Switzerland, West Germany, Austria, Belgium, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Japan etc. though cuts and closures of entire systems also happened there as the example of Hamburg shows. In France, only the networks in Lille, Saint-Étienne and Marseille, survive from this period, but they all suffered significant reduction from their original size. In Great Britain, only the Blackpool Tramway kept running, with an extensive system which includes some street running in Blackpool, and a long stretch of segregated track to nearby Fleetwood.

Resurgences

[edit]

The priority given to personal vehicles and notably to the automobile led to a loss in quality of life, particularly in large cities where smog, traffic congestion, sound pollution and parking became problematic. Acknowledging this, some authorities saw fit to redefine their transport policies. Rapid transit required a heavy investment and presented problems in terms of subterranean spaces that required constant security. For rapid transit, the investment was mainly in underground construction, which made it impossible in some cities (with underground water reserves, archaeological remains, etc.). Metro construction thus was not a universal panacea.

The advantages of the tram thus became once again visible. At the end of the 1970s, some governments studied, and then built new tram lines. In Germany the Stadtbahnwagen B was a modern tram (or tram-train) hybrid built to run on heavy rail tracks in a premetro type of system. The renaissance of light rail in North America began in 1978 when the Canadian city of Edmonton adopted the German Siemens-Duewag U2 system, followed three years later by Calgary and San Diego.

1980s and 1990s

[edit]Britain began replacing its run-down local railways with light rail in the 1980s, starting with the Tyne & Wear Metro in Tyneside followed by the Docklands Light Railway in London. The trend to light rail in the United Kingdom was firmly established with the success of the Manchester Metrolink system and Sheffield Supertram in 1992, followed by Midland Metro in Birmingham in 1999, and Tramlink in London in 2000.

In France, Nantes and Grenoble led the way in terms of the modern tram, and new systems were inaugurated in 1985 and 1988. In 1994 Strasbourg opened a system with novel British-built trams, specified by the city, with the goal of breaking with the archaic conceptual image that was held by the public.

A great example of this shift in ideology is the city of Munich, which began replacing its tram network with a metro a few years before the 1972 Summer Olympics. When the metro network was finished in the 1990s the city began to tear out the tram network (which had become rather old and decrepit), but now faced opposition from many citizens who enjoyed the enhanced mobility of the mixed network—the metro lines deviate from the tramlines to a significant degree. New rolling stock was purchased and the system was modernized, and a new line was proposed in 2003.

In Berlin, in 1990, ADtranz low floor tram, the world's first completely low floor tram was introduced.[citation needed] West Berlin had shut down its trams in the 1960s but the East reversed a previous decision to shut down the tramway network and new lines have been laid into the western part of Berlin after reunification.

21st century

[edit]The 2004 Summer Olympics resulted in the return of trams to Athens: the Athens Tram was integrated with the expanded Athens Metro system, as well as the buses, trolleybuses and suburban trains.

In Melbourne, Australia, the already extensive tramway system continues to be extended. In 2004 the Mont Albert line was extended several kilometres to Box Hill, whilst in 2005 the Burwood East line was extended several kilometres to Vermont South. In Sydney, trams returned in the form of light rail with the opening of the Inner West Light Rail line in 1997, which has seen extensions and now covers 7.2 mi (11.6 km).

In Prague, in 2009, Škoda 15 T, the world's first completely low-floor tram with articulated bogies was introduced.

In Scotland, Edinburgh relaunched its tram network on 31 May 2014[59] after delayed development which began in 2008. Edinburgh previously had an extensive tram network which began closure in the 1950s.[60] The new network is significantly smaller, 8.7 mi (14.0 km), compared to the previous tram network, 47.3 mi (76.1 km)

Systems such as tram-trains are bringing rail-based transit to areas that never had it and would not otherwise have gotten it. The Karlsruhe model was one of the first in the modern era and provided one-seat rides where several connections would have been necessary before, increasing ridership by significant amounts upon opening of service compared to the prior bus or local train routes.

Modern development

[edit]While many networks closed down during the postwar decades, the rolling stock on remaining systems kept developing, with multi-car trains (or articulated trams) with double-end designs and automatic control systems, allowing a single driver to serve more passengers, and decreasing turnaround time. Passenger and driver comfort have improved with stuffed seats and cabin heating. Advertising on trams, including all-over striping, became common.

The resurgence in the late 20th and 21st century has seen development of new technologies such as driverless automatic train operation in trams in Potsdam,[61] low-floor trams and regenerative braking.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Cable Car Home Page – Cable Car Lines in New York and New Jersey". cable-car-guy.com. Retrieved 24 December 2024.

Third Avenue Railroad cars run between the elevated structures through the Bowery.

- ^ Haupt, Herman (1893). Street railway motors. H.C. Baird & Company.

The subjects here considered are horse railroads steam motors cable traction electric roads com pressed air motors ammonia motors hot water motors gas motors and carbonic acid motors

- ^ The Technologist: Especially Devoted to Engineering, Manufacturing and Building. Industrial publishing Company. 1870. p. 48.

[S]treet railways can not compete with Metropolitan steam railways Street railways will certainly be able to effect certain advantages can not be attained by Metropolitan railways but where such judiciously introduced the horse railways become at once auxiliaries This condition of the subject we believe is not fully comprehended their introduction into London For the absence of any means of street transit in London except by stages called there omnibuses or hacks cabs and other vehicular and limited means on the introduction of the splendid system of Metropolitan railways both tunnel and overhead Whereas in New York the apparent comprehensiveness of the street railway system demand for a through steam track is unceasing and universal Albany will this session be the battle ground upon which may prob ably rest the decision for an underground railroad under Broadway So great is the popular and monetary influence brought to bear the New York Arcade Railway that its speedy introduction may be looked for.

- ^ "Proposed 'arcade railway' below Broadway would aid 1860s gridlock | 6sqft".

- ^ "The Swansea and Mumbles Railway – the world's first railway service". Welshwales.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ The John Stephenson Car Co. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- ^ Bellis, Mary. "History of Streetcars and Cable Cars". Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ "Siemens History Site – Transportation". Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ "New York Loses its Last Horse Car" The New York Times 29 July 191, page 12

- ^ "Sulphur Rock Street Car; Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture". Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ Allen Morrison. "The Indomitable Tramways of Celaya". Retrieved 22 December 2008.

- ^ Clark, Daniel Kinnear (1878). Tramways: Their Construction and Working, Embracing a Comprehensive History of the System, with an Exhaustive Analysis of the Various Modes of Traction ... With Special Reference to the Tramways of the United Kingdom. p. 313.

Mr Leonard J Todd of Leith it appears was the first steam locomotist who in 1871 designed an engine for tramways specially adapted for passing through common roads and streets avoiding noise smoke and steam and possessing great facilities for starting and for stopping quickly.

- ^ United States Census Office: Report on Transportation Business in the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890: Street railways. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1892. p. 10.

- ^ Souttar, Robinson (1877). Street Tranways: With an Abstract of the Discussion Upon the Paper. W. Clowes. pp. 16–17.

1. Steam Engine and Car. … 2. Detached Engines. …

- ^ "1876–1964 (Überblick)". Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ Stoomtram in en om Den Haag en Gouda, R. F. de Bock, Wyt Publishers, 1972, ISBN 90 6007 642 7.

- ^ The Engineer. Morgan-Grampian (Publishers). 1873.

- ^ Robertson, Andrew (March 1848). "Blackwall Railway Machinery". The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. 11. New York: Wiley & Putnam.

- ^ Borzo, Greg (2012). Chicago Cable Cars. The History Press. pp. 15–21. ISBN 978-1-60949-327-1.

- ^ From ABC-TV's 'Can you help?'. Sydney, the largest city in Australia, once had the largest tram system in Australia, the second largest in the Commonwealth (after London), and one of the largest in the world. In the early 1960s the entire network was dismantled.

- ^ Trams in Sydney

- ^ "Vauxhall, Oval & Kennington – The Brixton Tramway". vauxhallandkennington.org.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ "WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1886". The Argus. Melbourne. 29 December 1886. p. 5. Retrieved 10 March 2013 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Isaacs, Albert (10 August 2012). "Australian Timetable Association" (PDF). austta.org.au. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ "mark the fitter: November 2008". Markthefitter.blogspot.com. 17 November 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ http://www.google.com.au/search?q=%22gas+tram%22+Northcote+history&rls=com.microsoft:en-au:IE-SearchBox&ie=UTF-8&oe=UTF-8&sourceid=ie7&rlz=1I7GGLL_en-GB&redir_esc=&ei=R1MvTpXqGamdmQW4ofga Archived 30 December 2012 at archive.today

- ^ "Cieplice lšskie Zdrój is one of the best known Silesian towns". Archived from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Malaysia: first compressed natural gas tram in the world will be ready next year". Natural Gas Journal. 22 February 2011. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "This is how some of the world's familiar..." Archived 1 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Popular Mechanics, May 1929, pg. 750. via Google Books.

- ^ "Leeds City Tramways Uniform". Tramway Systems of the British Isles. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ American Public Transportation Association. "Milestones in U.S. Public Transportation History". Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- ^ Wood, E. Thomas. "Nashville now and then: From here to there". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ a b c Kaempffert & Martin 1924, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b c Hammond 2011, p. 142.

- ^ "Professor Sidney Howe Short experiments with motors". Fort Worth Daily Gazette. Fort Worth, Texas. 11 November 1894 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Sidney Howe Short". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Grace's Guide Ltd. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- ^ "Street Railways his hobby". Topeka Daily Capital. Topeka, Kansas. 14 November 1894 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Malone 1928, p. 128.

- ^ "Sarajevo Official Web Site : Sarajevo through history". Sarajevo.ba. 29 June 1914. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "City of Belgrade – Important Years in City History". Beograd.org.rs. 5 October 2000. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Trams of Hungary and much more". Hampage.hu. Archived from the original on 2 March 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "RATB – Regia Autonoma de Transport București". Ratb.ro. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "Historical Highlights". Ljubljanski potniški promet [Ljubljana Passenger Transport]. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ Green, Robert (1989). The first electric road : a history of the Box Hill and Doncaster tramway. East Brighton, Victoria: John Mason Press. ISBN 0731667158.

- ^ Kyoto Tram from Kyoto City Web. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ The Rebirth of Trams from the JFS Newsletter, December 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ Wordpress.com Archived 29 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, "The transport politic"

- ^ Electrifying America by David E. Nye, p.86, from Google Books. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ Thomas Davenport from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Archived 16 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 February 2009.

- ^ UK, DVV Media. "Battery trams running in Nanjing". Railway Gazette International. Archived from the original on 14 January 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Portland Tram – Google Search". Google.com.au. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ^ "China Presents the World's First Hydrogen-Fueled Tram".

- ^ "China Develops World's First Hydrogen-Powered Tram". IFLScience. 24 March 2015.

- ^ Conférence sur Alphonse LOUBAT, inventeur du tramway Archived 22 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine. In French. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ John Prentice: Tramway Origins and Pioneers. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Toronto Transport Commission – History. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). lava.net. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Transit Ridership – Rail vs. Bus". APTA Streetcar and Heritage Trolley Site. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Edinburgh tram starting date revealed as 31 May". BBC. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Granton History: Edinburgh tram routes". Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Connolly, Kate (23 September 2018). "Germany launches world's first autonomous tram in Potsdam". The Guardian.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hammond, John Winthrop (2011) [1941]. Men and volts; the story of General Electric. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA; London, UK: General Electric Company; J. B. Lippincott & Co.; Literary Licensing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-258-03284-5 – via Internet archive.

He was to produce the first motor that operated without gears of any sort, having its armature direct-connected to the car axle.

{{cite book}}: External link in|via= - Kaempffert, Waldemar Bernhard, Editor; Martin, T. Comerford (1924). A Popular History of American Invention. Vol. 1. London, UK; New York, USA: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved 11 March 2017 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Malone, Dumas (1928). Sidney Howe Short. Vol. 17. London, UK; New York, USA: Charles Scribner's Sons.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)