Human voice

The human voice consists of sound made by a human being using the vocal tract, including talking, singing, laughing, crying, screaming, shouting, humming or yelling. The human voice frequency is specifically a part of human sound production in which the vocal folds (vocal cords) are the primary sound source. (Other sound production mechanisms produced from the same general area of the body involve the production of unvoiced consonants, clicks, whistling and whispering.)

Generally speaking, the mechanism for generating the human voice can be subdivided into three parts; the lungs, the vocal folds within the larynx (voice box), and the articulators. The lungs, the "pump" must produce adequate airflow and air pressure to vibrate vocal folds. The vocal folds (vocal cords) then vibrate to use airflow from the lungs to create audible pulses that form the laryngeal sound source.[1] The muscles of the larynx adjust the length and tension of the vocal folds to 'fine-tune' pitch and tone. The articulators (the parts of the vocal tract above the larynx consisting of tongue, palate, cheek, lips, etc.) articulate and filter the sound emanating from the larynx and to some degree can interact with the laryngeal airflow to strengthen or weaken it as a sound source.

The vocal folds, in combination with the articulators, are capable of producing highly intricate arrays of sound.[2][3][4] The tone of voice may be modulated to suggest emotions such as anger, surprise, fear, happiness or sadness. The human voice is used to express emotion,[5] and can also reveal the age and sex of the speaker.[6][7][8] Singers use the human voice as an instrument for creating music.[9]

Voice types and the folds (cords) themselves

Adult men and women typically have different sizes of vocal fold; reflecting the male–female differences in larynx size. Adult male voices are usually lower-pitched and have larger folds. The male vocal folds (which would be measured vertically in the opposite diagram), are between 17 mm and 25 mm in length.[10] The female vocal folds are between 12.5 mm and 17.5 mm in length.

The folds are within the larynx. They are attached at the back (side nearest the spinal cord) to the arytenoids cartilages, and at the front (side under the chin) to the thyroid cartilage. They have no outer edge as they blend into the side of the breathing tube (the illustration is out of date and does not show this well) while their inner edges or "margins" are free to vibrate (the hole). They have a three layer construction of an epithelium, vocal ligament, then muscle (vocalis muscle), which can shorten and bulge the folds. They are flat triangular bands and are pearly white in color. Above both sides of the vocal cord is the vestibular fold or false vocal cord, which has a small sac between its two folds.

The difference in vocal fold size between men and women means that they have differently pitched voices. There is also genetic variation amongst the same sex, with men's and women's singing voices being categorized into types. For example, among men, there are bass, bass-baritone, baritone, baritenor, tenor and countertenor (ranging from E2 to C♯7 and higher), and among women, contralto, alto, mezzo-soprano and soprano (ranging from F3 to C6 and higher). There are additional categories for operatic voices, see voice type. This is not the only source of difference between male and female voice. Men, generally speaking, have a larger vocal tract, which essentially gives the resultant voice a lower-sounding timbre. This is mostly independent of the vocal folds themselves.

Voice modulation in spoken language

Human spoken language makes use of the ability of almost all people in a given society to dynamically modulate certain parameters of the laryngeal voice source in a consistent manner. The most important communicative, or phonetic, parameters are the voice pitch (determined by the vibratory frequency of the vocal folds) and the degree of separation of the vocal folds, referred to as vocal fold adduction (coming together) or abduction (separating).[11]

The ability to vary the ab/adduction of the vocal folds quickly has a strong genetic component, since vocal fold adduction has a life-preserving function in keeping food from passing into the lungs, in addition to the covering action of the epiglottis. Consequently, the muscles that control this action are among the fastest in the body.[11] Children can learn to use this action consistently during speech at an early age, as they learn to speak the difference between utterances such as "apa" (having an abductory–adductory gesture for the p) as "aba" (having no abductory–adductory gesture).[11] They can learn to do this well before the age of two by listening only to the voices of adults around them who have voices much different from their own, and even though the laryngeal movements causing these phonetic differentiations are deep in the throat and not visible to them.

If an abductory movement or adductory movement is strong enough, the vibrations of the vocal folds will stop (or not start). If the gesture is abductory and is part of a speech sound, the sound will be called voiceless. However, voiceless speech sounds are sometimes better identified as containing an abductory gesture, even if the gesture was not strong enough to stop the vocal folds from vibrating. This anomalous feature of voiceless speech sounds is better understood if it is realized that it is the change in the spectral qualities of the voice as abduction proceeds that is the primary acoustic attribute that the listener attends to when identifying a voiceless speech sound, and not simply the presence or absence of voice (periodic energy).[12]

An adductory gesture is also identified by the change in voice spectral energy it produces. Thus, a speech sound having an adductory gesture may be referred to as a "glottal stop" even if the vocal fold vibrations do not entirely stop.[12]

Other aspects of the voice, such as variations in the regularity of vibration, are also used for communication, and are important for the trained voice user to master, but are more rarely used in the formal phonetic code of a spoken language.

Physiology and vocal timbre

The sound of each individual's voice is thought to be entirely unique[13] not only because of the actual shape and size of an individual's vocal cords but also due to the size and shape of the rest of that person's body, especially the vocal tract, and the manner in which the speech sounds are habitually formed and articulated. (It is this latter aspect of the sound of the voice that can be mimicked by skilled performers.) Humans have vocal folds that can loosen, tighten, or change their thickness, and over which breath can be transferred at varying pressures. The shape of chest and neck, the position of the tongue, and the tightness of otherwise unrelated muscles can be altered. Any one of these actions results in a change in pitch, volume, timbre, or tone of the sound produced. Sound also resonates within different parts of the body, and an individual's size and bone structure can affect somewhat the sound produced by an individual.

Singers can also learn to project sound in certain ways so that it resonates better within their vocal tract. This is known as vocal resonation. Another major influence on vocal sound and production is the function of the larynx, which people can manipulate in different ways to produce different sounds. These different kinds of laryngeal function are described as different kinds of vocal registers.[14] The primary method for singers to accomplish this is through the use of the singer's formant, which has been shown to be a resonance added to the normal resonances of the vocal tract above the frequency range of most instruments and so enables the singer's voice to carry better over musical accompaniment.[15][16]

Vocal registration

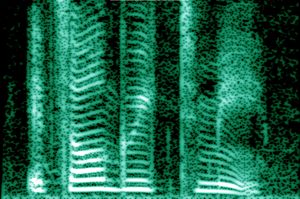

Vocal registration refers to the system of vocal registers within the human voice. A register in the human voice is a particular series of tones, produced in the same vibratory pattern of the vocal folds, and possessing the same quality. Registers originate in laryngeal functioning. They occur because the vocal folds are capable of producing several different vibratory patterns.[17] Each of these vibratory patterns appears within a particular Vocal range of pitches and produces certain characteristic sounds.[18] The occurrence of registers has also been attributed to effects of the acoustic interaction between the vocal fold oscillation and the vocal tract.[19] The term register can be somewhat confusing as it encompasses several aspects of the human voice. The term register can be used to refer to any of the following:[20]

- A particular part of the vocal range such as the upper, middle, or lower registers.

- A resonance area such as chest voice or head voice.

- A phonatory process.

- A certain vocal timbre.

- A region of the voice that is defined or delimited by vocal breaks.

- A subset of a language used for a particular purpose or in a particular social setting.

In linguistics, a register language is a language that combines tone and vowel phonation into a single phonological system.

Within speech pathology, the term vocal register has three constituent elements: a certain vibratory pattern of the vocal folds, a certain series of pitches, and a certain type of sound. Speech pathologists identify four vocal registers based on the physiology of laryngeal function: the vocal fry register, the modal register, the falsetto register, and the whistle register. This view is also adopted by many vocal pedagogists.[20]

Vocal resonation

Vocal resonation is the process by which the basic product of phonation is enhanced in timbre and/or intensity by the air-filled cavities through which it passes on its way to the outside air. Various terms related to the resonation process include amplification, enrichment, enlargement, improvement, intensification, and prolongation; although in strictly scientific usage acoustic authorities would question most of them. The main point to be drawn from these terms by a singer or speaker is that the result of resonation is, or should be, to make a better sound.[20] There are seven areas that may be listed as possible vocal resonators. In sequence from the lowest within the body to the highest, these areas are the chest, the tracheal tree, the larynx itself, the pharynx, the oral cavity, the nasal cavity, and the sinuses.[21]

Influences of the human voice

The twelve-tone musical scale, upon which a large portion of all music (western popular music in particular) is based, may have its roots in the sound of the human voice during the course of evolution, according to a study published by the New Scientist. Analysis of recorded speech samples found peaks in acoustic energy that mirrored the distances between notes in the twelve-tone scale.[22]

Voice disorders

There are many disorders that affect the human voice; these include speech impediments, and growths and lesions on the vocal folds. Talking improperly for long periods of time causes vocal loading, which is stress inflicted on the speech organs. When vocal injury is done, often an ENT specialist may be able to help, but the best treatment is the prevention of injuries through good vocal production.[23] Voice therapy is generally delivered by a speech-language pathologist.

Vocal cord nodules and polyps

Vocal nodules are caused over time by repeated abuse of the vocal cords which results in soft, swollen spots on each vocal cord.[24] These spots develop into harder, callous-like growths called nodules. The longer the abuse occurs the larger and stiffer the nodules will become. Most polyps are larger than nodules and may be called by other names, such as polypoid degeneration or Reinke's edema. Polyps are caused by a single occurrence and may require surgical removal. Irritation after the removal may then lead to nodules if additional irritation persists. Speech-language therapy teaches the patient how to eliminate the irritations permanently through habit changes and vocal hygiene. Hoarseness or breathiness that lasts for more than two weeks is a common symptom of an underlying voice disorder such as nodes or polyps and should be investigated medically.[25]

See also

- Accent (sociolinguistics)

- Acoustic phonetics

- Belt (music)

- Histology of the Vocal Folds

- Intelligibility (communication)

- List of voice actors

- Lombard effect

- Manner of articulation

- Paralanguage: nonverbal voice cues in communication

- Phonation

- Phonetics

- Puberphonia

- Speaker recognition

- Speaker verification

- Speech synthesis

- Vocal rest

- Vocal warm up

- Vocology

- Voice analysis

- Voice change in boys

- Voice disorders

- Voice frequency

- Voice organ

- Voicing (music), a representation of a chord

- Voice pedagogy

- Voice (phonetics): a property of speech sounds (especially consonants)

- Voice risk analysis

- Voice synthesis

- Voice therapy

- Voice vote

- World Voice Day

References

- ^ "About the voice". Lionsvoiceclinic.umn.edu. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ Stevens, K.N.(2000), Acoustic Phonetics, MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-69250-3, 978-0-262-69250-2

- ^ Titze, I.R. (1994). Principles of Voice Production, Prentice Hall (currently published by NCVS.org), ISBN 978-0-13-717893-3.

- ^ Titze, I. R. (2006). The Myoelatic Aerodynamic Theory of Phonation, Iowa City:National Center for Voice and Speech, 2006.

- ^ Johar, Swati (22 December 2015). Emotion, Affect and Personality in Speech: The Bias of Language and Paralanguage. SpringerBriefs in Speech Technology. Springer. pp. 10, 12. ISBN 978-3-319-28047-9.

- ^ Bachorowski, Jo-Anne (1999). "Vocal Expression and Perception of Emotions" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 8 (2): 53–57. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00013. S2CID 18785659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Smith, BL; Brown, BL; Strong, WJ; Rencher, AC (1975). "Effects of speech rate on personality perception". Language and Speech. 18 (2): 145–52. doi:10.1177/002383097501800203. PMID 1195957. S2CID 23498388.

- ^ Williams, CE; Stevens, KN (1972). "Emotions and speech: some acoustical correlates". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 52 (4): 1238–50. Bibcode:1972ASAJ...52.1238W. doi:10.1121/1.1913238. PMID 4638039.

- ^ Titze, IR; Mapes, S; Story, B (1994). "Acoustics of the tenor high voice". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 95 (2): 1133–42. Bibcode:1994ASAJ...95.1133T. doi:10.1121/1.408461. PMID 8132903.

- ^ Thurman, Leon & Welch, ed., Graham (2000), Body mind & voice: Foundations of voice education (revised ed.), Collegeville, Minnesota: The Voice Care Network et al., ISBN 0-87414-123-0

- ^ a b c "Breath-Stream Dynamics". Rothenberg.org. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Rothenberg, M. The glottal volume velocity waveform during loose and tight voiced glottal adjustments, Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, 22–28 August 1971 ed. by A. Rigault and R. Charbonneau, published in 1972 by Mouton, The Hague – Paris" (PDF). Rothenberg.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Is Every Human Voice and Fingerprint Really Unique?". The Conversation. 11 August 2016.

- ^ Vennard, William (1967). singing: The Mechanism and the Technic. Carl Fischer. ISBN 978-0-8258-0055-9.

- ^ Sundberg, Johan, The Acoustics of the Singing Voice, Scientific American Mar 77, p82

- ^ E. J. Hunter, J. G. Svec, and I. R. Titze. Comparison of the Produced and Perceived Voice Range Profiles in Untrained and Trained Classical Singers. J. Voice 2005.

- ^ Lucero, Jorge C. (1996). "Chest- and falsetto-like oscillations in a two-mass model of the vocal folds". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 100 (5): 3355–3359. Bibcode:1996ASAJ..100.3355L. doi:10.1121/1.416976. ISSN 0001-4966.

- ^ Large, John (February–March 1972). "Towards an Integrated Physiologic-Acoustic Theory of Vocal Registers". The NATS Bulletin. 28: 30–35.

- ^ Lucero, Jorge C.; Lourenço, Kélem G.; Hermant, Nicolas; Hirtum, Annemie Van; Pelorson, Xavier (2012). "Effect of source–tract acoustical coupling on the oscillation onset of the vocal folds" (PDF). The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 132 (1): 403–411. Bibcode:2012ASAJ..132..403L. doi:10.1121/1.4728170. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 22779487. S2CID 29954321.

- ^ a b c McKinney, James (1994). The Diagnosis and Correction of Vocal Faults. Genovex Music Group. ISBN 978-1-56593-940-0.

- ^ Greene, Margaret; Lesley Mathieson (2001). The Voice and its Disorders. John Wiley & Sons; 6th Edition. ISBN 978-1-86156-196-1.

- ^ Farley, Peter. "Musical roots may lie in human voice". New Scientist. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ "Fine Tuning Your Voice". stayhealthymn.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ "The Voice - Casting, Contestants, Auditions, Voting and Winners". The Voice 2020 Season 18. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Clark A. Rosen-Deborah Anderson-Thomas Murry (June 1998). "Evaluating Hoarseness: Keeping Your Patient's Voice Healthy". aafp.org. 57 (11): 2775. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

Further reading

- Howard, D.M., and Murphy, D.T.M. (2009). Voice Science, Acoustics, and Recording Voice science acoustics and recording, San Diego: Plural Press.

- Titze, I. R. (2008). The human instrument. Sci. Am. 298 (1):94–101. The Human Instrument

- Thurman, Leon & Welch, ed., Graham (2000), Bodymind & voice: Foundations of voice education (revised ed.), Collegeville, Minnesota: The VoiceCare Network et al., ISBN 0-87414-123-0

External links

- Free Voice analyzer and Biometrics displaying software from University College London (archived 24 September 2006)

- The Head Voice and Other Problems, 1917, by D. A. Clippinger, from Project Gutenberg

- The Voice Foundation's official website

- The Anatomy of Singing Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- David Harper, vocal coach: A passion for the voice that never wanes – Opera article (archived 11 September 2009)

- Irish Voice festival official website

- How the voice works – The Voice Works Like a Car (video on YouTube)

- Voice acoustics: an introduction from the University of New South Wales.

- Speak and Choke 1, by Karl S. Kruszelnicki, ABC Science, News in Science, 2002.