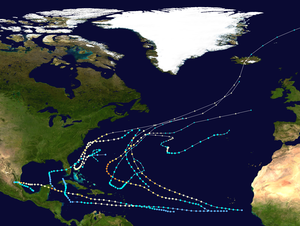

1951 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1951 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | January 4, 1951 |

| Last system dissipated | December 11, 1951 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Easy |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 937 mbar (hPa; 27.67 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 17 |

| Total storms | 12 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 276+ overall |

| Total damage | $80 million (1951 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 1951 Atlantic hurricane season was the first hurricane season in which tropical cyclones were officially named by the United States Weather Bureau.[1] The season officially started on June 15, when the United States Weather Bureau began its daily monitoring for tropical cyclone activity;[2] the season officially ended on November 15.[3] It was the first year since 1937 in which no hurricanes made landfall on the United States;[4] as Hurricane How was the only tropical storm to hit the nation, the season had the least tropical cyclone damage in the United States since the 1939 season.[5] As in the 1950 season, names from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet were used to name storms this season.[6]

The first hurricane of the season, Able, formed prior to the official start of the season; before reanalysis in 2015, it was once listed as the earliest major hurricane on record in the Atlantic basin. It formed on May 16 and executed a counterclockwise loop over the Bahamas; later it brushed the North Carolina coastline. Hurricane Charlie was a powerful Category 4 hurricane that struck Jamaica as a major hurricane, killing hundreds and becoming the worst disaster in over 50 years. The hurricane later struck Mexico twice as a major hurricane, producing deadly flooding outside of Tampico, Tamaulipas. The strongest hurricane, Easy, spent its duration over the open Atlantic Ocean, briefly threatening Bermuda, and was formerly listed as one of a relatively few Category 5 hurricanes on record over the Atlantic Ocean. It briefly neared Category 5 status and interacted with Hurricane Fox, marking the first known instance of a hurricane affecting another's path.

Timeline

[edit]

Systems

[edit]Tropical Storm One

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | January 4 – January 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

As the calendar entered the new year, cyclogenesis occurred with an extratropical frontal wave over the western North Atlantic Ocean due to a closed low forming in a mid-level trough, which eventually produced a low-pressure center at the surface by January 2. Ships recorded moderate gales up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h) in connection with the new surface low, which formed several hundred miles east-southeast of Bermuda.[7] While initially lacking tropical attributes, the cyclone headed southeast for two days before curving southwestward.[8] As it did so, the temperature of the system warmed in its lower levels, causing the cyclone to evolve into a more barotropic system. Late on January 4, the system shrank in size and began developing an inner core; reanalysis determined that the system became a tropical storm at this time, though it would have likely been considered subtropical beginning in the early 1970s.[7]

Hurricane Able

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 16 – May 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

The origins of the first hurricane of the season were from a trough that exited the East Coast of the United States on May 12. A low-pressure area developed on May 14, and two days later it developed into a tropical cyclone about 300 miles (480 km) south of Bermuda. It formed beneath an upper-level low, and initially was not fully tropical. The depression followed the low, initially toward the northwest and later the southwest. Moving over the Gulf Stream, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Able on May 16.[9] The storm turned to the south, and Hurricane Hunters reported that Able strengthened to hurricane status on May 17 off the coast of Florida.[5]

The outer rainbands of Able produced light rainfall and high seas along the Florida coastline.[10] It later moved through the northern Bahamas early on May 18, where it produced hurricane-force winds of 85 mph (137 km/h).[8] The hurricane later turned to the north, gradually strengthening through May 21. Shortly thereafter, Able passed about 70 miles (110 km) east of Cape Hatteras before turning east and reaching its peak of 90 mph (140 km/h) early on May 22.[5][8] Along the coast, the hurricane produced high tides but little damage.[11] Able maintained hurricane intensity for two more days before weakening to a tropical storm early on May 24.[8] Able rapidly dissipated that same day, though originally it was assessed as having evolved into an extratropical cyclone on May 23.[5]

Until 2015, Able was listed as having peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and was analyzed to have been the earliest major hurricane on record. Such a storm would be a Category 3 or greater on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, a system developed and introduced in the 1970s.[12] Able was also the strongest hurricane outside of the current hurricane season (June 1 through November 30).[13] However, reanalysis by scientists in 2015 determined that Able was in fact far weaker than originally listed in HURDAT, the official database containing information on storm tracks and intensities in the Atlantic and Eastern North Pacific regions. It also lost its distinction as the strongest preseason cyclone on record, the record being held by a Category 2 hurricane in March 1908.[8] The hurricane was one of four North Atlantic hurricanes on record to exist during the month of May, the others occurring in 1889, 1908, and 1970.[8]

Tropical Storm Baker

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 2 – August 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

On August 2, an easterly wave spawned a tropical depression about 680 miles (1,090 km) northeast of Barbuda in the Lesser Antilles. It moved northwestward, quickly strengthening into Tropical Storm Baker. Early on August 3, the storm attained peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h), and the next day passed about 275 mi (443 km) east of Bermuda.[5] At its peak intensity, the gale-force winds extended 100 miles (160 km) to the north of the center.[14] After attaining its peak, Baker quickly weakened on August 4 and turned to the northeast.[8] Early the next day, it regained some of its former strength before losing its identity. Baker never affected land.[5]

Hurricane Charlie

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 12 – August 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); ≤958 mbar (hPa) |

The third tropical cyclone of the season developed on August 12 from a tropical wave, 930 miles (1,500 km) east-southeast of Barbados. After a few days without further development, the system intensified into Tropical Storm Charlie on August 14, and subsequently crossed through the Lesser Antilles a day later with winds of 70 mph (113 km/h).[8] Shortly after entering the Caribbean Sea, the storm intensified to hurricane status early on August 16. Passing south of Puerto Rico and Hispaniola, Charlie then underwent rapid deepening beginning late that day, its winds increasing 35 mph (56 km/h) in 24 hours.[8] As it neared the island of Jamaica early on August 18, Charlie became a major hurricane and shortly afterward struck just south of Kingston with winds of 125 mph (201 km/h)—equivalent to a strong Category 3 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale, making Charlie, along with Hurricane Gilbert in 1988, the strongest ever to hit the island.[5][8] On the island, the hurricane dropped heavy rainfall up to 17 in (430 mm). The combination of strong winds and the rains left around $50 million (1951 USD, $380 million 2005 USD) in crop and property damage. Across the country there were 152 deaths, 2,000 injuries, and 25,000 people left homeless; as a result, it was considered the worst disaster in the country in the 20th century until Hurricane Gilbert produced even costlier damage, though with fewer reported fatalities.[5][15][16]

After making landfall, Charlie weakened in its passage over the mountainous center of Jamaica, and by the time it left the island, its winds had diminished to 85 mph (137 km/h).[8] Charlie later passed south of the Cayman Islands, with Grand Cayman reporting peak wind gusts of 92 mph (148 km/h).[5] As it did so, the storm began to undergo yet another period of rapid intensification beginning on August 19. It regained major hurricane status late that day, and early on August 20 Charlie peaked at 130 mph (210 km/h), equivalent to low-end Category 4 status.[8] Maintaining its strength, the hurricane then made landfall on the southern tip of Cozumel and hit the Mexican mainland near Akumal on the Yucatán Peninsula. The strong winds destroyed 70% of the crops along its path, although no deaths were reported in the Yucatán Peninsula.[5] Several homes were wrecked in the region.[17] As it moved inland, Charlie weakened rapidly over land, reaching the Bay of Campeche as a minimal hurricane early on August 21.[8] Once over water, it failed to re-intensify for a full day, but began doing so early on August 22. As it did so, it rapidly re-intensified for a third and final time, reaching peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) before striking near the city of Miramar, just north of Tampico.[8] It dissipated on August 23. The hurricane dropped heavy rainfall in the region, flooding rivers and causing dams to burst. The hurricane killed 257 people in Mexico. Across Charlie's entire path, damage was estimated at over $75 million (1951 USD).[18][5] The outer fringes of the storm increased surf along the Texas coast.[19]

Hurricane Dog

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 27 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); ≤992 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave spawned a tropical depression on August 27 southwest of Cape Verde.[5][8] It moved westward, eventually intensifying into a tropical storm early on August 31.[8] The next day, the storm was first observed by Hurricane Hunters, several hundred miles east of Barbados, and it was named "Dog".[5] By that time, its winds were around 60 mph (97 km/h), and the storm continued intensifying as it approached the Lesser Antilles.[8] On September 2, Dog attained hurricane status,[5] reaching its peak of 90 mph (140 km/h) as it passed between the islands of Saint Lucia and Martinique.[8] The storm, then quite small in diameter, produced strong wind gusts of up to 115 mph (185 km/h) at the airport in Fort-de-France on Martinique.[5] However, this peak was short-lived, for upon entering the eastern Caribbean Sea Dog began a slow but steady weakening trend. On September 4, Dog weakened to tropical storm status to the south of Hispaniola, and the next day dissipated in the western Caribbean.[8]

In northern Saint Lucia, the combination of flooding and high winds destroyed 70% of the banana crop. Two sailing vessels were destroyed, and another one damaged. Across the island, Hurricane Dog killed two people from drownings.[5] Damage was heavier on Martinique, located on the north side of the storm. The hurricane's winds destroyed 1,000 homes and the roofs of several others. Downed trees blocked roads and disrupted power lines. The winds also destroyed 90% of the banana crop and 30% of the sugar cane. Throughout Martinique, Dog left $3 million in damage (1951 USD, $35.2 million 2025 USD) and killed five people from drownings.[5] It was considered the "most violent storm" in Martinique in 20 years.[20] Initially the hurricane was expected to strike Jamaica, prompting hurricane warnings for the country, as well as along the southern coast of Hispaniola.[20] Jamaica was struck by Hurricane Charlie a few weeks prior, and the threat from Dog prompted coastal evacuations and the closure of an airport.[21] Ultimately, Dog dissipated and produced only light rainfall on the island.[22]

Hurricane Easy

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); ≤937 mbar (hPa) |

Hurricane Easy, the strongest tropical cyclone of the season, was a powerful and long-lived Cape Verde-type hurricane that originated as a tropical depression on September 1 between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde.[8] Moving generally west-northwestward, the depression deepened into a tropical storm late that day, and further to hurricane status by September 3. On September 5, the cyclone reached its first peak of 110 mph (177 km/h), but failed to continue strengthening. Its winds fluctuated through the early morning on September 6, but then resumed strengthening, reaching major hurricane status by that evening.[8] During this period, Hurricane Hunters flew into the hurricane to monitor its progress, recording a minimum pressure of 957 millibars (28.26 inHg) on September 6 to the north of the Lesser Antilles.[5] The next day, an aircraft was unable to penetrate the center, estimating winds of 160 mph (257 km/h) south of the eye. On this basis, Easy was once classified as a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale;[23] A reanalysis in 2015 lowered the peak winds to 150 mph (240 km/h) on September 8. This was based on the Hurricane Hunters reporting a pressure of 937 mb (27.67 inHg) on the previous day, and a ship reporting winds of 140 mph (230 km/h).[23] By the time Easy attained peak intensity, it had turned to the north and northeast while beginning a steady weakening trend.[5][8] It interacted with the small Hurricane Fox to the east; this was the first observed instance of a hurricane affecting another's path.[5][24] Easy then turned to the northeast, passing a short distance southeast of Bermuda on September 9 with winds of 110 mph (177 km/h).[8] Easy evolved into an extratropical cyclone late on September 11, while still maintaining hurricane-force winds. The remnants lost their hurricane-force winds on September 12, only to briefly regain them two days later. On September 14, Easy lost its identity over the northern Atlantic Ocean after it was absorbed by another extratropical storm to the north.[23]

The Weather Bureau advised Bermuda to take precautionary measures in advance of the storm;[25] tourists and residents "worked feverishly" to complete preparations, and the United States Air Force issued "a formal warning at noon."[26] Numerous hotels and homes were shuttered. Heavy traffic snarled evacuations, and 100 tourists were stranded on the island without "roundtrip reservations." Air Force aircraft returned to the United States, and personnel secured various facilities at the island's base.[26] On Bermuda, the hurricane produced winds of only 50 mph (80 km/h), which downed a few banana trees.[24] In addition to affecting Bermuda, the strong winds of the hurricane damaged a few ships along its path.[5]

Hurricane Fox

[edit]| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 2 – September 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); ≤978 mbar (hPa) |

Around the same time as Easy was forming, a new tropical depression developed in the far eastern Atlantic Ocean. Moving generally westward, it passed south of the Cape Verde islands, quickly strengthening into Tropical Storm Fox early on September 3; by that time, its motion turned to the west-northwest.[8] On September 5, Fox attained hurricane status, around the same time as it was first observed by ships. Two days later, Hurricane Hunters reported peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h), making it a major hurricane, albeit one of very small extent.[5] Around that time, Fox interacted with Hurricane Easy to its northwest. After maintaining peak winds for 12 hours, Fox began a steady weakening trend, accelerating to the north and northeast ahead of Easy and passing to the east of Bermuda. On September 10, Fox, while still of hurricane force, became extratropical between the Azores and Greenland in the far north Atlantic. It turned towards the north and dissipated on September 11 off the southwest coast of Iceland. Although a few ships were affected by the hurricane's winds, there were no reports of any damage.[5][8]

Tropical Storm George

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 19 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Storm George developed in the Bay of Campeche on September 19. Moving west-northwestward, it quickly attained peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) late on the next day, as reported by the Hurricane Hunters.[5][8] George later made landfall on September 21 in Mexico about 55 mi (89 km) south of Tampico as a moderate tropical storm.[5][8] Before it moved ashore, the storm spread rainfall along the coast and increased waves, causing one drowning death.[27] George quickly dissipated upon making landfall, and there were no reports of damage.[5]

Hurricane How

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 29 – October 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 972 mbar (hPa) |

An easterly wave spawned a tropical depression in the western Caribbean Sea on September 29. It moved north-northwestward for a few days before turning eastward in the central Gulf of Mexico.[8] Based on Hurricane Hunter reports, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm How late on September 30, and it continued to strengthen as it approached Southwest Florida. On October 2, How attained its first peak of 65 mph (105 km/h) just before making landfall near Boca Grande, and within the day it crossed southern Florida.[8] At the time, the storm was not well organized, and its strongest winds were confined to squalls in the Florida Keys and the southeast coast.[5] Wind damage was minor, although heavy rainfall was reported,[5] peaking at 15.7 inches (40 cm) near where it moved ashore.[28] The precipitation caused significant street flooding, while about 7,000 acres (28 km2) of tomato and bean fields were deluged.[29][30]

The storm emerged into the Atlantic Ocean between Fort Pierce and Vero Beach, quickly intensifying to hurricane strength by October 3. Turning northeastward, How reached its second and strongest peak of 100 mph (161 km/h) on October 4 as it passed near the Outer Banks of North Carolina.[5][8] Along the coast, the hurricane produced high tides and minor damage.[31] Subsequently, the hurricane briefly weakened, only to recover its peak of 100 mph (160 km/h) on October 5.[8] It passed southeast of Cape Cod before turning more to the east-northeast,[5] causing road closures due to high tides.[31] Offshore, the hurricane sank a ship, killing 17 people.[32] While still of hurricane force, How became an extratropical storm on October 6, and a few days later it curved to the northeast. The extratropical cyclone later struck Iceland with hurricane-force winds on October 9.[8] A couple of days later, the remnants of How dissipated in the far northern Atlantic.[5] Overall, Hurricane How caused about $2 million (1951 USD, $23.5 million 2025 USD) in damage.[5]

Tropical Storm Item

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 12 – October 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed southwest of Jamaica on October 12. A small system, it moved northwestward and intensified into Tropical Storm Item on October 13. It turned toward the north, and the next day attained peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) after moving through the Cayman Islands. Based on observations from the Hurricane Hunters, Item was upgraded to hurricane status in real time, although a reanalysis in 2015 lowered the peak winds to 65 mph (105 km/h).[5][8] Item lost tropical storm status on October 16 as it drifted to the northwest. Continuing a slow weakening trend, it passed just east of the Isla de la Juventud before striking western Cuba as a tropical depression on October 17. Later that day it dissipated in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico.[5][8]

The threat of the hurricane prompted precautions to be made in parts of Cuba. Additionally, storm warnings were posted in the Florida Keys, southern mainland Florida, as well as the Bahamas.[33] However, no damage was reported.[5]

Hurricane Jig

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 15 – October 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

One of the last tropical cyclones of the season formed on October 15 just northeast of the Bahamas. Although listed as a tropical storm, it would have likely been classified as a subtropical cyclone beginning in the 1970s, but was unable to be classified as such given the lack of satellite imagery to prove its status. Given the name "Jig", it moved northeastward, quickly attaining hurricane status with winds of 75 mph (121 km/h), which it maintained for a full day.[8] On October 16, Jig began a slow weakening trend, weakening below hurricane force and turning sharply northeastward. During this time, the storm made its closest approach to the southeastern United States while passing well southeast of Cape Hatteras.[5][8] While offshore, the storm increased surf along the North Carolina and Virginia coastlines, prompting storm warnings.[34] Early October 18, Jig became extratropical with winds of 70 mph (113 km/h) and began a counterclockwise loop over the western Atlantic. The next day it turned to the southeast before dissipating about 230 mi (370 km) south of Bermuda on October 20.[5][8]

Hurricane Twelve

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | December 2 – December 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); ≤995 mbar (hPa) |

In early December, a cold front passed north of Bermuda. A disturbance along the front began rotating on December 2, developing into a small but powerful extratropical storm on the next day. By late on December 3, the storm attained hurricane-force winds, and it increasingly became the dominant system within the broad frontal region. A ridge to the east turned this storm to the southwest. The winds diminished below hurricane-intensity on December 5, and concurrently the inner structure became more tropical as the frontal features dissipated. During this time, ships in the region reported strong winds, mostly to the north. Increasing water temperatures fueled atmospheric instability, likely causing an increase in convection, and the system was potentially a subtropical cyclone on December 6, while located about 1,015 mi (1,633 km) east-northeast of Bermuda. A nearby ship recorded a minimum pressure of 987 mbar (29.1 inHg) around that time. After the storm turned to the southeast, a ship in the region reported winds of 75 mph (121 km/h) near the center and a pressure of 995 mbar (29.4 inHg), while a weather station indicated that the system had a warm core. The data suggested that the system became a fully tropical hurricane by 12:00 UTC on December 7, and that it likely had evolved into a tropical storm six hours earlier. By 18:00 UTC that night, the hurricane attained peak winds of 80 mph (130 km/h).[23]

On December 8, the hurricane turned to the east and weakened into a tropical storm, steered by an approaching trough. Over the next day, the storm accelerated to the east-northeast toward the Azores. Late on December 10, the storm moved through the Azores as a tropical storm, although it was reverting to an extratropical storm at the time. By 06:00 UTC on December 11, the system was extratropical again after it rejoined with a nearby cold front. It likely merged with another nontropical storm to its east on December 12, although it is possible the former hurricane remained a distinct system. A building ridge near Spain forced the extratropical system to the southeast, eventually dissipating after coming ashore in Morocco on December 15.[23]

Storm names

[edit]The Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet was used to name cyclones that attained at least tropical storm status in the North Atlantic in 1951.[35]

|

|

|

See also

[edit]- 1951 Pacific hurricane season

- 1951 Pacific typhoon season

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 1950–51 1951–52

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1950–51 1951–52

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1950–51 1951–52

References

[edit]- ^ Neal Dorst (October 23, 2012). "They Called the Wind Mahina: The History of Naming Cyclones". Hurricane Research Division, Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. Slides 62–72.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-06-15). "Hurricane Warning System to Begin Tonight". The News and Courier. Retrieved 2011-01-09.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-11-15). "Hurricane Season Ends, Said Mildest". The Victoria Advocate. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; et al. (January 2022). Continental United States Hurricanes (Detailed Description). Re-Analysis Project (Report). Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Grady Norton (1952). "Hurricanes of 1951" (PDF). Weather Bureau Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-25. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Chris Landsea (2007). "Subject: B1) How are tropical cyclones named?". Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (May 2015). "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT) Meta Data". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2015-05-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 4, 2025.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Landsea, Chris (April 2022). "The revised Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT2) - Chris Landsea – April 2022" (PDF). Hurricane Research Division – NOAA/AOML. Miami: Hurricane Research Division – via Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory.

- ^ Paul Moore and Walter Davis (1951). "A Preseason Hurricane of Subtropical Origin" (PDF). Weather Bureau Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-14. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ United Press (1951-05-18). "Hurricane Hits Florida Coast". Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-05-21). "Drought Spreads Into Southland". Ellensburg Daily Record. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Jack Williams (May 17, 2005). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Neil Dorst (2009). "Subject: G1) When is hurricane season?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 5 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-02.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-08-04). "Tropical Storm Rages off Bermuda". Toledo Blade. United Press International. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Joseph B. Treaster (1988-09-15). "Jamaica Counts the Hurricane Toll: 25 Dead and 4 Out of 5 Homes Roofless". New York Times. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- ^ Pan American Health Organization Emergency Preparedness and Disaster Relief Coordination Program. (1999-02-20) "The Hurricane and its Effects: Hurricane Gilbert - Jamaica" Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine. Centro Regional de Información sobre Desastres América Latina y El Caribe. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-08-20). "Hurricane "Charlie" Heads Towards Mexico". Valley Morning Star.

- ^ "Hurricane Toll Rises to 413". Racine Journal Times. United Press. September 1, 1951. p. 2.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-08-23). "Rain Cuts Heat Wave". The Galveston Daily News.

- ^ a b Staff Writer (1951-09-03). "Hurricane Threatens Jamaica; Another Born". The News and Courier. Associated Press. Retrieved 10 January 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-09-04). "Hurricane Loses Velocity, Veers; Jamaica Spared". Sarasota Herald. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ^ Bella Kelly (1951-09-05). "Third Hurricane Found; Second One Rejuvenated". Miami Daily News. p. 1A. Retrieved 2021-02-19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Chris Landsea; et al. (May 2015). Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (1951) (Report). Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ^ a b Staff Writer (1951-09-10). "Two Hurricanes Duel at Sea". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ International News Service (1951). "Bermuda Set For Hurricane". The Galveston Daily News.

- ^ a b United Press (1951). "Big Blow Nears Bermuda". Waterloo Sunday Courier.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-09-21). "Storm Hits Mexican Coast; Sweeps Inland". St. Joseph G. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Roth, David M. (May 12, 2022). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in Florida". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Storm Causes Widespread Damage in South Florida". Associated Press. 1951. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ David M. Roth (2013-01-07). "The Climatology for Quantitative Rainfall (CLIQR) for tropical cyclones graphical user interface extended best track database". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ^ a b "Hurricane Not Expected to Hit Main Hard". Lewiston Evening Journal. Associated Press. 1951-10-05. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ United States Coast Guard (1952). "Marine Board of Investigation; foundering MV Southern Isles in position 32º30'N 73º00'W, 5 October 1951, with loss of life" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-09. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-10-15). "Small But Dangerous Hurricane Nears Cuba". Tri City Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved 2011-01-08.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Staff Writer (1951-10-16). "Eastern Coast Hit by Storm". Greensburg Daily Tribune. United Press International. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ^ Gary Padgett (2007). "History of the Naming of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, Part 1 - The Fabulous Fifties". Retrieved 2011-01-13.