Xi Jinping

Xi Jinping | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

习近平 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Xi in 2024 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assumed office 15 November 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assumed office 14 March 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Military Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Assumed office

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First-ranked Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 22 October 2007 – 15 November 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General Secretary | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zeng Qinghong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Liu Yunshan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice President of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 15 March 2008 – 14 March 2013 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Hu Jintao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zeng Qinghong | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Li Yuanchao | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 15 June 1953 Beijing, China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | CCP (since 1974) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Xi Mingze | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Qi Qiaoqiao (sister) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence | Zhongnanhai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Tsinghua University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Full list | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

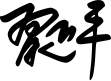

| Signature |  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www.gov.cn (in Chinese) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thesis | Research on China's Rural Marketization (2001) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doctoral advisor | Liu Meixun (刘美珣) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 习近平 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 習近平 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Central institution membership

Leading Groups and Commissions

Other offices held

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Xi Jinping[a] (born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and thus the paramount leader of China, since 2012. Xi has been serving as the seventh president of China since 2013. As a member of the fifth generation of Chinese leadership, Xi is the first CCP general secretary born after the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC).

The son of Chinese communist veteran Xi Zhongxun, Xi was exiled to rural Yanchuan County as a teenager following his father's purge during the Cultural Revolution. He lived in a yaodong in the village of Liangjiahe, Shaanxi province, where he joined the CCP after several failed attempts and worked as the local party secretary. After studying chemical engineering at Tsinghua University as a worker-peasant-soldier student, Xi rose through the ranks politically in China's coastal provinces. Xi was governor of Fujian from 1999 to 2002, before becoming governor and party secretary of neighboring Zhejiang from 2002 to 2007. Following the dismissal of the party secretary of Shanghai, Chen Liangyu, Xi was transferred to replace him for a brief period in 2007. He subsequently joined the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) of the CCP the same year and was the first-ranking secretary of the Central Secretariat in October 2007. In 2008, he was designated as Hu Jintao's presumed successor as paramount leader. Towards this end, Xi was appointed vice president of the PRC and vice chairman of the CMC. He officially received the title of leadership core from the CCP in 2016.

While overseeing China's domestic policy, Xi has introduced far-ranging measures to enforce party discipline and strengthen internal unity. His anti-corruption campaign led to the downfall of prominent incumbent and retired CCP officials, including former PSC member Zhou Yongkang. For the sake of promoting "common prosperity", Xi has enacted a series of policies designed to increase equality, overseen targeted poverty alleviation programs, and directed a broad crackdown in 2021 against the tech and tutoring sectors. Furthermore, he has expanded support for state-owned enterprises (SOEs), advanced military-civil fusion, and attempted to reform China's property sector. Following the onset of COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China, he initially presided over a zero-COVID policy from January 2020 to December 2022 before ultimately shifting towards a mitigation strategy.

Xi has pursued a more aggressive foreign policy, particularly with regard to China's relations with the U.S., the nine-dash line in the South China Sea, and the Sino-Indian border dispute. Additionally, for the sake of advancing Chinese economic interests abroad, Xi has sought to expand China's influence in Africa and Eurasia by championing the Belt and Road Initiative. Despite meeting with Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou in 2015, Xi presided over a deterioration in relations between Beijing and Taipei under Ma's successor, Tsai Ing-wen. In 2020, Xi oversaw the passage of a national security law in Hong Kong which clamped down on political opposition in the city, especially pro-democracy activists.

Since coming to power, Xi's tenure has witnessed a significant increase in censorship and mass surveillance, a deterioration in human rights, including the internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, the rise of a cult of personality around his leadership, and the removal of term limits for the presidency in 2018. Xi's political ideas and principles, known as Xi Jinping Thought, have been incorporated into the party and national constitutions. As the central figure of the fifth generation of leadership of the PRC, Xi has centralized institutional power by taking on multiple positions, including new CCP committees on national security, economic and social reforms, military restructuring and modernization, and the internet. In October 2022, Xi secured a third term as CCP General Secretary, and was re-elected state president for a third term in March 2023.

Early life and education

Xi Jinping was born on 15 June 1953 in Beijing,[2] the third child of Xi Zhongxun and his second wife Qi Xin. After the founding of the PRC in 1949, Xi's father held a series of posts, including the chief of the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party, vice-premier, and vice chairperson of the National People's Congress.[3] Xi had two older sisters, Qiaoqiao, born in 1949 and An'an (安安; Ān'ān), born in 1952.[4] Xi's father was from Fuping County, Shaanxi.[5]

Xi went to the Beijing Bayi School,[6][7] and then the Beijing No. 25 School,[8] in the 1960s. He became friends with Liu He, who attended Beijing No. 101 School in the same district, and who later became China's vice premier and a close advisor to Xi after he became China's paramount leader.[9][10] In 1963, when he was aged 10, his father was purged from the CCP and sent to work in a factory in Luoyang, Henan.[11] In May 1966, the Cultural Revolution cut short Xi's secondary education when all secondary classes were halted for students to criticise and fight their teachers. Student militants ransacked the Xi family home and one of Xi's sisters, Xi Heping, "was persecuted to death."[12][13]

Later, his mother was forced to publicly denounce his father, as he was paraded before a crowd as an enemy of the revolution. His father was later imprisoned in 1968 when Xi was aged 15. In 1968, Xi submitted an application to the Bayi School's Reform Committee and insisted on leaving Beijing for the countryside.[14] On January 13, 1969, they left Beijing and arrived in Liangjiahe Village, Yan'an, Shaanxi, alongside the Mao Zedong's Down to the Countryside Movement.[15] The rural areas of Yan'an were very backward,[16] which created a big gap for Xi as a teenager. He once recalled that he had to overcome "five hurdles" (flea, food, life, labor and thought hurdle),[17] and the experience led him to feel affinity with the rural poor.[16] After a few months, unable to stand rural life, he ran away to Beijing. He was arrested during a crackdown on deserters from the countryside and sent to a work camp to dig ditches, but he later returned to the village, under the persuasion of his aunt Qi Yun and uncle Wei Zhenwu.[18] He worked as the party secretary of Liangjiahe, where he lived in a cave house.[19]

He then spent a total of seven years in Yanchuan.[20][21] In 1973, Yanchuan County assigned Xi Jinping to Zhaojiahe Village in Jiajianping Commune to lead social education efforts.[22] Due to his effective work and strong rapport with the villagers, the community expressed a desire to keep him there. However, after Liangjiahe Village advocated for his return, Xi went back in July that same year. Liang Yuming (梁玉明) and Liang Youhua (梁有华), the village branch secretaries, supported his application to the Chinese Communist Party.[23] Yet, due to his father, Xi Zhongxun, still facing political persecution, the application was initially blocked by higher authorities.[7] Despite submitting ten applications, it wasn't until the new commune secretary, Bai Guangxing (白光兴), recognized Xi's capabilities that his application was forwarded to the CCP Yanchuan County Committee and approved in early 1974.[24] Around that time, as Liangjiahe village underwent leadership changes, Xi was recommended to become the Party branch chairman of the Liangjiahe Brigade.[25][26]

After taking office, Xi noted that Mianyang, Sichuan was using biogas technology and, given the fuel shortages in his village, he traveled to Mianyang to learn about biogas digesters.[27] Upon returning, he successfully implemented the technology in Liangjiahe, marking a breakthrough in Shaanxi that soon spread throughout the region.[28] Additionally, he led efforts to drill wells for water supply, establish iron industry cooperatives, reclaim land, plant flue-cured tobacco, and set up sales outlets to address the village's production and economic challenges.[29][30] In 1975, when Yanchuan County was allocated a spot at Tsinghua University, the CCP Yanchuan County Committee recommended Xi for admission.[31] From 1975 to 1979, Xi studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua University as a worker-peasant-soldier student in Beijing.[32][33]

Early political career

Central Military Commission

After graduating in April 1979, Xi was assigned to the General Office of the State Council and the General Office of the CPC Central Military Commission, where he served as one of three secretaries to Geng Biao,[34] a member of the CPC Central Committee's Political Bureau and Minister of Defense.[35][7]

Hebei

On March 25, 1982, Xi was appointed deputy party secretary of Zhengding County in Hebei.[36][37] Together with Lü Yulan (吕玉兰), the other deputy party secretary of Zhengding, Xi wrote a letter to the center government addressing the excessive requisitions that burdened local farmers.[38] Their efforts successfully convinced the center government to reduce the annual requisition amount by 14 million kilograms.[22] In 1983, Zhengding adjusted its agricultural structure, leading to a significant increase in farmers' incomes from 148 yuan to over 400 yuan in 1984,[39] thoroughly solving the county's economic issues.[40]

As the secretary of the CCP Zhengding County Committee in July 1983,[41][38] Xi initiated several development projects, including the development of "Nine Articles of Zhengding talents",[41] the construction of Changshan Park,[42] the restoration of the Longxing Temple, the formation of a tourism company, and the establishment of the Rongguo Mansion and Zhengding Table Tennis Base.[43] He also persuaded the China Teleplay Production Center to set the filming base of Dream of the Red Mansions in Zhengding and secured 3.5 million yuan to build Rongguo Mansion,[44] which significantly boosted the county's tourism industry, generating 17.61 million yuan in revenue that year.[45] Additionally, Xi invited prominent figures such as Hua Luogeng, Yu Guangyuan, Pan Chengxiao to visit Zhengding,[46] which eventually led to the development of the county's "semi-urban" strategy,[43] leveraging its proximity to Shijiazhuang for diverse business growth.[47][48]

In September 1984, during a briefing session chaired by He Zai, the secretary-general of the Central Organization Department, Xi Jinping's strategic vision and comprehensive understanding of Zhengding County's development were highlighted.[49] He Zai, along with Wei Jianxing, deputy head of the CCP Central Organization Department, communicated these findings to Hu Yaobang, describing Xi as a leader with a strategic outlook and a strong alliance ideology between workers and peasants.[50][51] In 1985, Xi participated in a study tour on corn processing and traveled to Iowa, US,[52] to study agricultural production and corn processing technology.[53][49] During his visit to the U.S., the CCP Central Organization Department decided to transfer him to Xiamen as a member of the Standing Committee of the CCP Xiamen Municipal Committee and as vice mayor.[50]

Fujian

Arriving in Xiamen as vice-mayor in June 1985, Xi drafted the development of the first strategic plan for the city, the Xiamen Economic and Social Development Strategy for 1985–2000.[54] From August, Along with helping to prepare Xiamen Airlines,[55] the Xiamen Economic Information Center,[56] and the Xiamen Special Administrative Region Road Project, etc, he oversaw the resolution for Yundang Lake's comprehensive treatments.[57] He married Peng Liyuan then in Xiamen.[58][59]

He started serving as the head of a region after being appointed just as the secretary of Ningde in September 1988.[60] and Ningde's economy was far worse at that time than that of Fuzhou and Xiamen.[61] Xi organized his work log and experience during his Ningde period into his book Getting out of Poverty,[62] and handled the local poverty eradicating efforts and local CCP building projects.[63] The CCP Fujian Provincial Committee decided in May 1990 to assign Xi to Fuzhou City as the Municipal Committee Secretary.[64]

In 1997, he was named an alternate member of the 15th CCP Central Committee. In 1999, he was promoted to the office of Vice Governor of Fujian, and became governor a year later. Xi proposed the concept of the Golden Triangle at Min River (Chinese: 闽江口金三角经济圈) and oversaw the construction of the Fuzhou 3820 Project Master Plan,[65] which outlines Fuzhou City's growth strategy for 3, 8, and 20 years.[66] He concentrated on the development of Changle International Airport, the Min River Water Transfer Project, the Fuzhou Telecommunication Hub, and Fuzhou Port, among others. He concentrated on attracting Taiwanese and foreign investment,[67] establishing Southwest TPV Electronics and Southeast Automobile in Fuzhou, and fostering Fuyao Glass, Newland Digital Technology and other manufacturing firms.[64] Furthermore, he rehabilitated local cultural landmarks, including as the Sanfang Qixiang in Fuzhou, advanced urban renewal initiatives, and effectively addressed the issue of poverty alleviation on Pingtan Island. In 1995, Xi Jinping was elevated to deputy secretary of the Fujian Provincial Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and served as Governor of Fujian from 1999 to 2002, during which he presented the notion of "Megalopolises" and advocated for the inter-island growth strategy of Fuzhou and Xiamen, which motivated local officials to swiftly overcome the repercussions of the Yuanhua smuggling case (Chinese: 远华走私案) and adopt a new development strategy.[68] Xi also oversaw the development of "Digital Fujian", including the province's complaint hotline into the "12345 Citizen Service Platform," so enhancing organizational efficiency. [65]

Zhejiang

In 2002, Xi left Fujian and took up leading political positions in neighbouring Zhejiang. He eventually took over as provincial Party Committee secretary after several months as acting governor, occupying a top provincial office for the first time in his career. In 2002, he was elected a full member of the 16th Central Committee, marking his ascension to the national stage. While in Zhejiang, Xi presided over reported growth rates averaging 14% per year.[69] During this period, Zhejiang increasingly transitioned away from heavy industry.[70]: 121 His career in Zhejiang was marked by a tough and straightforward stance against corrupt officials. This earned him a name in the national media and drew the attention of China's top leaders.[71] Between 2004 and 2007, Li Qiang acted as Xi's chief of staff through his position as secretary-general of the Zhejiang Party Committee, where they developed close mutual ties.[72]

Shanghai

Following the dismissal of Shanghai Party secretary Chen Liangyu in September 2006 due to a social security fund scandal, Xi was transferred to Shanghai in March 2007, where he was the party secretary there for seven months.[73][74] In Shanghai, Xi avoided controversy and was known for strictly observing party discipline. For example, Shanghai administrators attempted to earn favour with him by arranging a special train to shuttle him between Shanghai and Hangzhou for him to complete handing off his work to his successor as Zhejiang party secretary Zhao Hongzhu. However, Xi reportedly refused to take the train, citing a loosely enforced party regulation that stipulated that special trains can only be reserved for "national leaders."[75] While in Shanghai, he worked on preserving unity of the local party organisation. He pledged there would be no 'purges' during his administration, despite the fact many local officials were thought to have been implicated in the Chen Liangyu corruption scandal.[76] On most issues, Xi largely echoed the line of the central leadership.[77]

Politburo Standing Committee

Xi was appointed to the nine-man PSC at the 17th Party Congress in October 2007. He was ranked above Li Keqiang, an indication that he was going to succeed Hu Jintao as China's next leader. In addition, Xi also held the first secretary of the CCP's Central Secretariat. This assessment was further supported at the 11th National People's Congress in March 2008, when Xi was elected as vice president of the PRC.[78] Following his elevation, Xi held a broad range of portfolios. He was put in charge of the comprehensive preparations for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, as well as being the central government's leading figure in Hong Kong and Macau affairs. In addition, he also became the new president of the Central Party School of the CCP, its cadre-training and ideological education wing. In the wake of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, Xi visited disaster areas in Shaanxi and Gansu. He made his first foreign trip as vice president to North Korea, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Yemen from 17 to 25 June 2008.[79] After the Olympics, Xi was assigned the post of committee chair for the preparations of the 60th Anniversary Celebrations of the founding of the PRC. He was also reportedly at the helm of a top-level CCP committee dubbed the 6521 Project, which was charged with ensuring social stability during a series of politically sensitive anniversaries in 2009.[80]

Xi's position as the apparent successor to become the paramount leader was threatened with the rapid rise of Bo Xilai, the party secretary of Chongqing at the time. Bo was expected to join the PSC at the 18th Party Congress, with most expecting that he would try to eventually maneuver himself into replacing Xi.[81] Bo's policies in Chongqing inspired imitations throughout China and received praise from Xi himself during Xi's visit to Chongqing in 2010. Records of praises from Xi were later erased after he became paramount leader. Bo's downfall would come with the Wang Lijun incident, which opened the door for Xi to come to power without challengers.[82]

Xi is considered one of the most successful members of the Princelings, a quasi-clique of politicians who are descendants of early Chinese Communist revolutionaries. Former prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, when asked about Xi, said he felt he was "a thoughtful man who has gone through many trials and tribulations."[83] Lee also commented: "I would put him in the Nelson Mandela class of persons. A person with enormous emotional stability who does not allow his personal misfortunes or sufferings affect his judgment. In other words, he is impressive."[84] Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson described Xi as "the kind of guy who knows how to get things over the goal line."[85] Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd said that Xi "has sufficient reformist, party and military background to be very much his own man."[86]

Trips as Vice President

In February 2009, in his capacity as vice-president, Xi embarked on a tour of Latin America, visiting Mexico, Jamaica,[87] Colombia, Venezuela,[88] Brazil,[89] and Malta, after which he returned to China.[90] On 11 February 2009, while visiting Mexico, Xi spoke in front of a group of overseas Chinese and explained China's contributions during the international financial crisis, saying that it was "the greatest contribution towards the whole of human race, made by China, to prevent its 1.3 billion people from hunger."[b] He went on to remark: "There are some bored foreigners, with full stomachs, who have nothing better to do than point fingers at us. First, China doesn't export revolution; second, China doesn't export hunger and poverty; third, China doesn't come and cause you headaches. What more is there to be said?"[c][91] The story was reported on some local television stations. The news led to a flood of discussions on Chinese Internet forums and it was reported that the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs was caught off-guard by Xi's remarks, as the actual video was shot by some accompanying Hong Kong reporters and broadcast on Hong Kong TV, which then turned up on various Internet video websites.[92]

In the European Union, Xi visited Belgium, Germany, Bulgaria, Hungary and Romania from 7 to 21 October 2009.[93] He visited Japan, South Korea, Cambodia, and Myanmar on his Asian trip from 14 to 22 December 2009.[94] He later visited the United States, Ireland and Turkey in February 2012. This visit included meeting with then U.S. president Barack Obama at the White House and vice president Joe Biden (with Biden as the official host);[95] and stops in California and Iowa. In Iowa, he met with the family that previously hosted him during his 1985 tour as a Hebei provincial official.[96]

Accession to top posts

A few months before his ascendancy to the party leadership, Xi disappeared from official media coverage and cancelled meetings with foreign officials for several weeks beginning on 1 September 2012, causing rumors.[7] He then reappeared on 15 September.[97] On 15 November 2012, Xi was elected to the posts of general secretary of the CCP and chairman of the CMC by the 18th Central Committee of the CCP. This made him, informally, the paramount leader and the first to be born after the founding of the PRC. The following day Xi led the new line-up of the PSC onto the stage in their first public appearance.[98] The PSC was reduced from nine to seven, with only Xi and Li Keqiang retaining their seats; the other five members were new.[99][100][101] In a marked departure from the common practice of Chinese leaders, Xi's first speech as general secretary was plainly worded and did not include any political slogans or mention his predecessors.[102] Xi mentioned the aspirations of the average person, remarking, "Our people ... expect better education, more stable jobs, better income, more reliable social security, medical care of a higher standard, more comfortable living conditions, and a more beautiful environment." Xi also vowed to tackle corruption at the highest levels, alluding that it would threaten the CCP's survival; he was reticent about far-reaching economic reforms.[103]

In December 2012, Xi visited Guangdong in his first trip outside Beijing since taking the Party leadership. The overarching theme of the trip was to call for further economic reform and a strengthened military. Xi visited the statue of Deng Xiaoping and his trip was described as following in the footsteps of Deng's own southern trip in 1992, which provided the impetus for further economic reforms in China after conservative party leaders stalled many of Deng's reforms in the aftermath of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. On his trip, Xi consistently alluded to his signature slogan, the "Chinese Dream." "This dream can be said to be the dream of a strong nation. And for the military, it is a dream of a strong military," Xi told sailors.[104] Xi's trip was significant in that he departed from the established convention of Chinese leaders' travel routines in multiple ways. Rather than dining out, Xi and his entourage ate regular hotel buffet. He travelled in a large van with his colleagues rather than a fleet of limousines, and did not restrict traffic on the parts of the highway he travelled.[105]

Xi was elected president on 14 March 2013, in a confirmation vote by the 12th National People's Congress in Beijing. He received 2,952 for, one vote against, and three abstentions.[98] He replaced Hu Jintao, who retired after serving two terms.[106] On 17 March, Xi and his new ministers arranged a meeting with the chief executive of Hong Kong, CY Leung, confirming his support for Leung.[107] Within hours of his election, Xi discussed cyber security and North Korea with U.S. President Barack Obama over the phone. Obama announced the visits of treasury and state secretaries Jack Lew and John F. Kerry to China the following week.[108]

Leadership

Anti-corruption campaign

"To speak the truth" means to focus on the nature of things, to speak frankly, and follow the truth. This is an important embodiment of a leading official's characteristics of truth seeking, embodying justice, devotion to public interests, and uprightness. Moreover, he highlighted that the premise of telling the truth is to listen to the truth.

Xi vowed to crack down on corruption immediately after he ascended to power. In his inaugural speech as general secretary, Xi mentioned that fighting corruption was one of the toughest challenges for the party.[110] A few months into his term, Xi outlined the Eight-point Regulation, listing rules intended to curb corruption and waste during official party business; it aimed at stricter discipline on the conduct of officials. Xi vowed to root out "tigers and flies," that is, high-ranking officials and ordinary party functionaries.[111]

Xi initiated cases against former CMC vice-chairmen Xu Caihou and Guo Boxiong, former PSC member and security chief Zhou Yongkang and former Hu Jintao chief aide Ling Jihua.[112] Along with new disciplinary chief Wang Qishan, Xi's administration spearheaded the formation of "centrally-dispatched inspection teams". These were cross-jurisdictional squads whose task was to gain understanding of the operations of provincial and local party organizations, and enforce party discipline mandated by Beijing. Work teams had the effect of identifying and initiating investigations of high-ranking officials. Over one hundred provincial-ministerial level officials were implicated during a nationwide anti-corruption campaign. These included former and current regional officials, leading figures of state-owned enterprises and central government organs, and generals. Within the first two years of the campaign alone, over 200,000 officials received warnings, fines, and demotions.[113]

The campaign has led to the downfall of prominent incumbent and retired CCP officials, including members of the PSC.[114] Xi's anti-corruption campaign is seen by critics, such as The Economist, as a political tool to remove potential opponents and consolidate power.[115][116] Xi's establishment of a new anti-corruption agency, the National Supervision Commission, ranked higher than the supreme court, has been described by Amnesty International as a "systemic threat to human rights" that "places tens of millions of people at the mercy of a secretive and virtually unaccountable system that is above the law."[117][118]

Xi has overseen significant reforms of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), CCP's highest internal control institution.[119] He and CCDI Secretary Wang Qishan further institutionalized CCDI's independence from the day-to-day operations of the CCP, improving its ability to function as a bona fide control body.[119] According to The Wall Street Journal, anti-corruption punishment to officials at or above the vice ministerial level need approval from Xi.[120] The Wall Street Journal said that when he wants to neutralize a political rival, he asks inspectors to prepare pages of evidence. It also said he authorizes investigations on close associates of a high-ranking politician, to replace them with his proteges and puts rivals in less important positions to separate them from their political bases. Reportedly, these tactics have even been used against Wang Qishan, Xi's close friend.[121]

According to sinologist Wang Gungwu, Xi inherited a party that was faced with pervasive corruption.[122][123] Xi believed corruption at the higher levels of the CCP put the party and country at risk of collapse.[122] Wang adds that Xi has a belief that only the CCP is capable of governing China, and that its collapse would be disastrous for the Chinese people. Xi and the new generational leaders reacted by launching the anti-corruption campaign to eliminate corruption at the higher levels of the government.[122]

Censorship

Since Xi became general secretary, censorship has stepped up.[124][125] Chairing the 2018 China Cyberspace Governance Conference, Xi committed to "fiercely crack down on criminal offenses including hacking, telecom fraud, and violation of citizens' privacy."[126] During a visit to Chinese state media, Xi stated that "party and government-owned media must hold the family name of the party" and that the state media "must embody the party's will, safeguard the party's authority."[127]

His administration has overseen more Internet restrictions imposed, and is described as being "stricter across the board" on speech than previous administrations.[128] Xi has taken a strong stand to control internet usage inside China, including Google and Facebook,[129] advocating Internet censorship under the concept of internet sovereignty.[130][131] The censorship of Wikipedia has been stringent; in April 2019, all versions of Wikipedia were blocked.[132] Likewise, the situation for users of Weibo has been described as a change from fearing one's account would be deleted, to fear of arrest.[133]

A law enacted in 2013 authorized a three-year prison term for bloggers who shared more than 500 times any content considered "defamatory."[134] The State Internet Information Department summoned influential bloggers to a seminar to instruct them to avoid writing about politics, the CCP, or making statements contradicting official narratives. Many bloggers stopped writing about controversial topics, and Weibo went into decline, with much of its readership shifting to WeChat users speaking to limited social circles.[134] In 2017, telecommunications carriers were instructed to block individuals' use of Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) by February 2018.[135]

Consolidation of power

Political observers have called Xi the most powerful Chinese leader since Mao Zedong, especially since the ending of presidential two-term limits in 2018.[136][137][138][139] Xi has departed from the collective leadership practices of post-Mao predecessors. He has centralised his power and created working groups with himself at the head to subvert government bureaucracy, making himself become the unmistakable central figure of the administration.[140] In the opinion of at least one political scientist, Xi "has surrounded himself with cadres he met while stationed on the coast, Fujian and Shanghai and in Zhejiang."[141]

Observers have said that Xi has seriously diluted the influence of the once-dominant "Tuanpai," also called the Youth League Faction, which were CCP officials who rose through the Communist Youth League (CYLC).[142] He criticized the cadres of the CYLC, saying that [these cadres] can't talk about science, literature and art, work or life [with young people]. All they can do is just repeat the same old bureaucratic, stereotypical talk."[143]

In 2018, the National People's Congress (NPC) passed constitutional amendments including removal of term limits for the president and vice president, the creation of a National Supervisory Commission, as well as enhancing the central role of the CCP.[144][145] Xi was reappointed as president, now without term limits,[146][147] while Li Keqiang was reappointed premier.[148] According to the Financial Times, Xi expressed his views of constitutional amendment at meetings with Chinese officials and foreign dignitaries. Xi explained the decision in terms of needing to align two more powerful posts—general secretary of the CCP and chairman of the CMC—which have no term limits. However, Xi did not say whether he intended to be party general secretary, CMC chairman and state president, for three or more terms.[149]

In its sixth plenary session in November 2021, CCP adopted a historical resolution, a kind of document that evaluated the party's history. This was the third of its kind after ones adopted by Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping.[150][151] In comparison with the other historical resolutions, Xi's one did not herald a major change in how the CCP evaluated its history.[152] To accompany the historical resolution, the CCP promoted the terms Two Establishes and Two Safeguards, calling the CCP to unite around and protect Xi's core status within the party.[153]

The 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, held between 16 and 22 October 2022, has overseen amendments in the CCP constitution and the re-election of Xi as general secretary of the CCP and chairman of the CMC for a third term, with the overall result of the Congress being further strengthening of Xi's power.[154] Xi's re-election made him the first party leader since Mao Zedong to be chosen for a third term, though Deng Xiaoping ruled the country informally for a longer period.[155] The new Politburo Standing Committee elected just after the CCP Congress was filled almost completely with people close to Xi, with four out of the seven members of the previous PSC stepping down.[156] Xi was further re-elected as the PRC president and chairman of the PRC Central Military Commission on 10 March 2023 during the opening of the 14th National People's Congress, while Xi ally Li Qiang succeeded Li Keqiang as the Premier.[157]

Cult of personality

Xi has had a cult of personality constructed around himself since entering office[158][159] with books, cartoons, pop songs and dance routines honouring his rule.[160] Following Xi's ascension to the leadership core of the CCP, he had been referred to as Xi Dada (习大大, Uncle or Papa Xi),[160][161] though this stopped in April 2016.[162] The village of Liangjiahe, where Xi was sent to work, is decorated with propaganda and murals extolling the formative years of his life.[163] The CCP's Politburo named Xi Jinping lingxiu (领袖), a reverent term for "leader" and a title previously only given to Mao Zedong and his immediate successor Hua Guofeng.[164][165][166] He is also sometimes called the "pilot at the helm" (领航掌舵).[167] On 25 December 2019, the Politburo officially named Xi as "People's Leader" (人民领袖; rénmín lǐngxiù), a title only Mao had held previously.[168]

Economy and technology

Xi was initially seen as a market reformist,[169] and a central committee under him announced "market forces" would begin to play a "decisive" role in allocating resources.[170] This meant that the state would gradually reduce its involvement in the distribution of capital, and restructure state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to allow further competition, potentially by attracting foreign and private sector players in industries previously highly regulated. This policy aimed to address the bloated state sector that had unduly profited from re-structuring by purchasing assets at below-market prices, assets no longer being used productively. Xi launched the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone in 2013, which was seen as part of the economic reforms.[171] However, by 2017, Xi's promise of economic reforms was said to have stalled by experts.[172][169] In 2015, the Chinese stock market bubble popped, which led Xi to use state forces to fix it.[173] From 2012 to 2022, the share of the market value of private sector firms in China's top listed companies increased from 10% to over 40%.[174] He has overseen the relaxation of restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) and increased cross-border holdings of stocks and bonds.[174]

Xi has increased state control over the economy, voicing support for SOEs,[175][169] while also supporting the private sector.[176] CCP control of SOEs has increased, while limited steps towards market liberalization, such as increasing mixed ownership of SOEs were undertaken.[177] Under Xi, "government guidance funds," public-private investment funds set up by or for government bodies, have raised more than $900 billion for early funding to companies that work in sectors the government deems as strategic.[178] His administration made it easier for banks to issue mortgages, increased foreign participation in the bond market, and increased the national currency renminbi's global role, helping it to join IMF's basket of special drawing right.[179] In 2018, he promised to continue reforms but warned nobody "can dictate to the Chinese people."[180]

Xi has made eradicating extreme poverty through targeted poverty alleviation a key goal.[181] In 2021, Xi declared a "complete victory" over extreme poverty, saying nearly 100 million have been lifted out of poverty under his tenure, though experts said China's poverty threshold was lower than that of the World Bank.[182] In 2020, premier Li Keqiang, citing the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) said that China still had 600 million people living with less than 1000 yuan ($140) a month, although The Economist said the methodology NBS used was flawed.[183] When Xi took office in 2012, 51% of people in China were living on less than $6.9 per day, in 2020 this had fallen 25%.[184]

China's economy has grown under Xi, doubling from $8.5 trillion in 2012 to $17.8 trillion in 2021,[185] while China's nominal GDP per capita surpassed the world average in 2021,[186] though growth has slowed from 8% in 2012 to 6% in 2019.[187] Xi has stressed the importance of "high-quality growth" rather than "inflated growth."[188] He has stated China has abandoned a growth-at-all-costs strategy which Xi refers to as "GDP heroism."[189]: 22 Instead, Xi said other social issues such as environmental protection are important.[189]: 22

Xi has circulated a policy called "dual circulation," meaning reorienting the economy towards domestic consumption while remaining open to foreign trade and investment.[190] Xi has prioritised boosting productivity.[191] Xi has attempted to reform the property sector to combat the steep increase in prices and cut the economy's dependence on it.[192] In the 19th CCP National Congress, Xi declared "Houses are built to be inhabited, not for speculation."[193] In 2020, Xi's government formulated the "three red lines" policy that aimed to deleverage the heavily indebted property sector.[194] Xi has supported a property tax, for which he has faced resistance from members of the CCP.[195] His administration pursued a debt-deleveraging campaign, seeking to slow and cut the unsustainable amount of debt China has accrued during its growth.[196]

Xi's administration has promoted "Made in China 2025" plan that aims to make China self-reliant in key technologies, although publicly China de-emphasised this plan due to the outbreak of a China–United States trade war. Since the outbreak of the trade war in 2018, Xi has revived calls for "self-reliance," especially on technology.[197] Domestic spending on R&D has significantly increased, surpassing the European Union (EU) and reaching a record $564 billion in 2020.[198] The Chinese government has supported technology companies like Huawei through grants, tax breaks, credit facilities and other assistance, enabling their rise but leading to US countermeasures.[199] In 2023, Xi put forward new productive forces, this refers to a new form of productive forces derived from continuous sci-tech breakthroughs and innovation that drive strategic emerging and future industries in a more intelligent information era.[200] Xi has been involved in the development of Xiong'an, a new area announced in 2017, planned to become a major metropolis near Beijing; the relocation aspect is estimated to last until 2035 while it is planned to developed into a "modern socialist city" by 2050.[201]

Common prosperity is an essential requirement of socialism and a key feature of Chinese-style modernization. The common prosperity we are pursuing is for all, affluence both in material and spiritual life, but not for a small portion nor for uniform egalitarianism.

In 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that Xi ordered a halt to Ant Group's initial public offering (IPO), in reaction to its founder Jack Ma criticizing government regulation in finance.[203] Xi's administration has overseen a decrease in offshore IPOs by Chinese companies, with most Chinese IPOs taking place either in Shanghai or Shenzhen as of 2022[update], and has increasingly directed funding to IPOs of companies that works in sectors it deems as strategic, including electric vehicles, biotechnology, renewable energy, artificial intelligence, semiconductors and other high-technology manufacturing.[178]

Since 2021, Xi has promoted the term "common prosperity," which he defined as an "essential requirement of socialism," described as affluence for all and said entailed reasonable adjustments to excess incomes.[202][204] Common prosperity has been used as the justification for large-scale crackdowns and regulations towards the perceived "excesses" of several sectors, most prominently tech and tutoring industries.[205] Actions taken include fining large tech companies[206] and passing laws such as the Data Security Law. China introduced severe restrictions on private tutoring companies, effectively destroying the whole industry.[207] Xi opened a new stock exchange in Beijing targeted for small and medium enterprises (SMEs).[208] There have been other cultural regulations including restrictions on minors playing video games and crackdowns on celebrity culture.[209][210]

Reforms

In November 2013, at the conclusion of the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee, the Communist Party delivered a far-reaching reform agenda that alluded to changes in both economic and social policy. Xi signaled at the plenum that he was consolidating control of the massive internal security organization that was formerly the domain of Zhou Yongkang.[170] A new National Security Commission was formed with Xi at its helm, which commentators have said would help Xi consolidate over national security affairs.[211][212]

The Central Leading Group for Comprehensively Deepening Reforms—another ad hoc policy coordination body led by Xi upgraded to a commission in 2018—was also formed to oversee the implementation of the reform agenda.[213][214] Termed "comprehensive deepening reforms" (全面深化改革; quánmiàn shēnhuà gǎigé), they were said to be the most significant since Deng Xiaoping's 1992 Southern Tour. The plenum also announced economic reforms and resolved to abolish the laogai system of "re-education through labour," which was largely seen as a blot on China's human rights record. The system has faced significant criticism for years from domestic critics and foreign observers.[170] In January 2016, a two-child policy replaced the one-child policy,[215] which was in turn was replaced with a three-child policy in May 2021.[216] In July 2021, all family size limits as well as penalties for exceeding them were removed.[217]

Political reforms

Xi's administration taken a number of changes to the structure of the CCP and state bodies, especially in a large overhaul in 2018. Beginning in 2013, the CCP under Xi has created a series of Central Leading Groups: supra-ministerial steering committees, designed to bypass existing institutions when making decisions, and ostensibly make policy-making a more efficient process. Xi was also believed to have diluted the authority of premier Li Keqiang, taking authority over the economy which has generally been considered to be the domain of the premier.[218][219]

February 2014 oversaw the creation of the Central Leading Group for Cybersecurity and Informatization with Xi as its leader. The State Internet Information Office (SIIO), previously under the State Council Information Office (SCI), was transferred to the central leading group and renamed in English into the Cyberspace Administration of China.[220] As part of managing the financial system, the Financial Stability and Development Committee, a State Council body, was established in 2017. Chaired by vice premier Liu He during its existence, the committee was disestablished by the newly established Central Financial Commission during the 2023 Party and state reforms.[221] Xi has increased the role of the Central Financial and Economic Affairs Commission at the expense of the State Council.[222]

2018 has seen larger reforms to the bureaucracy. In that year, several central leading groups including reform, cyberspace affairs, finance and economics. and foreign affairs were upgraded to commissions.[223] The powers of the Central Propaganda Department was strengthened, which now oversaw the newly established China Media Group (CMG).[223] Two State Council departments. one dealing with overseas Chinese, and other one dealing with religious affairs, were merged into the United Front Work Department while another commission dealing with ethnic affairs was brought under formal UFWD leadership.[223] In 2020, all elections at all levels of the people's congress system and NPC were mandated to adhere to the leadership of the CCP.[224]

2023 has seen further reforms to the CCP and state bureaucracy, most notably the strengthening of Party control over the financial and technology domains.[225] This included the creation of two CCP bodies for overseeing finance; the Central Financial Commission (CFC), as well as the revival of the Central Financial Work Commission (CFWC) that was previously dissolved in 2002.[225] Additionally, a new CCP Central Science and Technology Commission would be established to broadly oversee the technology sector, while a newly created Social Work Department was tasked with CCP interactions with several sectors, including civic groups, chambers of commerce and industry groups, as well as handling public petition and grievance work.[225] Regulatory bodies saw large overhauls.[226] Several regulatory responsibilities were also transferred from the People's Bank of China (PBoC) to another regulatory body, while the PBoC reopened offices around the country that were closed in a previous reorganization.[227] In 2024, the CCP's role was strengthened further with the State Council regulations amended to add a clause about following CCP ideology and policies.[228]

Legal reforms

Efforts should be made to enable the people to see that justice is served in every judicial case.

The party under Xi announced a raft of legal reforms at the Fourth Plenum held in the fall 2014, and he called for "Chinese socialistic rule of law" immediately afterwards. The party aimed to reform the legal system, which had been perceived as ineffective at delivering justice and affected by corruption, local government interference and lack of constitutional oversight. The plenum, while emphasizing the absolute leadership of the party, also called for a greater role of the constitution in the affairs of state and a strengthening of the role of the National People's Congress Standing Committee in interpreting the constitution.[230] It also called for more transparency in legal proceedings, more involvement of ordinary citizens in the legislative process, and an overall "professionalization" of the legal workforce. The party also planned to institute cross-jurisdictional circuit legal tribunals as well as giving provinces consolidated administrative oversight over lower level legal resources, which is intended to reduce local government involvement in legal proceedings.[231]

Military reforms

Since taking power in 2012, Xi has undertaken an overhaul of the People's Liberation Army, including both political reform and its modernization.[232] Military-civil fusion has advanced under Xi.[233][234] Xi has been active in his participation in military affairs, taking a direct hands-on approach to military reform. In addition to being the Chairman of the CMC and leader of the Central Leading Group for Military Reform founded in 2014 to oversee comprehensive military reforms, Xi has delivered numerous high-profile pronouncements vowing to clean up malfeasance and complacency in the military. Xi has repeatedly warned that the depoliticization of the PLA from the CCP would lead to a collapse similar to that of the Soviet Union.[235] Xi held the New Gutian Conference in 2014, gathering China's top military officers, re-emphasizing the principle of "the party has absolute control over the army" first established by Mao at the 1929 Gutian Conference.[236]

In the USSR, where the military was depoliticized, separated from the party and nationalized, the party was disarmed. When the Soviet Union came to crisis point, a big party was gone just like that. Proportionally, the Soviet Communist Party had more members than we do, but nobody was man enough to stand up and resist.

Xi announced a reduction of 300,000 troops from the PLA in 2015, bringing its size to 2 million troops. Xi described this as a gesture of peace, while analysts such as Rory Medcalf have said that the cut was done to reduce costs as well as part of PLA's modernization.[238] In 2016, he reduced the number of theater commands of the PLA from seven to five.[239] He has also abolished the four autonomous general departments of the PLA, replacing them with 15 agencies directly reporting to the CMC.[232] Two new branches of the PLA were created under his reforms, the Strategic Support Force[240] and the Joint Logistics Support Force.[241] In 2018, the PAP was placed under the sole control of the CMC; the PAP was previously under the joint command of the CMC and the State Council through the Ministry of Public Security.[242]: 15

On 21 April 2016, Xi was named commander-in-chief of the country's new Joint Operations Command Center of the PLA by Xinhua News Agency and the broadcaster China Central Television.[243][244] Some analysts interpreted this move as an attempt to display strength and strong leadership and as being more "political than military."[245] According to Ni Lexiong, a military affairs expert, Xi "not only controls the military but also does it in an absolute manner, and that in wartime, he is ready to command personally."[246] According to a University of California, San Diego expert on Chinese military, Xi "has been able to take political control of the military to an extent that exceeds what Mao and Deng have done."[247]

Under Xi, China's official military budget has more than doubled,[198] reaching a record $224 billion in 2023.[248] Though predating Xi, his administration has taken a more assertive stance towards maritime affairs, and has boosted CCP control over the maritime security forces.[249] The PLA Navy has grown rapidly under Xi, with China adding more warships, submarines, support ships and major amphibious vessels than the entire number of ships under the United Kingdom navy between 2014 and 2018.[250] In 2017, China established the navy's first overseas base in Djibouti.[251] Xi has also undertaken an expansion of China's nuclear arsenal, with him calling China to "establish a strong system of strategic deterrence." The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has estimated China's total amount of nuclear arsenals to be 410 in 2023, with the US Department of Defense estimating that China's arsenal could reach 1,000 by 2030.[252]

Foreign policy

Xi has taken a harder line on security issues as well as foreign affairs, projecting a more nationalistic and assertive China on the world stage.[253] His political program calls for a China more united and confident of its own value system and political structure.[254] Foreign analysts and observers have frequently said that Xi's main foreign policy objective is to restore China's position on the global stage as a great power.[255][237][256] Xi advocates "baseline thinking" in China's foreign policy: setting explicit red lines that other countries must not cross.[257] In the Chinese perspective, these tough stances on baseline issues reduce strategic uncertainty, preventing other nations from misjudging China's positions or underestimating China's resolve in asserting what it perceives to be in its national interest.[257] Xi stated during the 20th CCP National Congress that he wanted to ensure China "leads the world in terms of composite national strength and international influence" by 2049.[258]

Xi has promoted "major-country diplomacy" (大国外交), stating that China is already a "big power" and breaking away from previous Chinese leaders who had a more precautious diplomacy.[259] He has adopted a hawkish foreign policy posture called "wolf warrior diplomacy,"[260] while his foreign policy thoughts are collectively known as "Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy."[261] In March 2021, he said that "the East is rising and the West is declining" (东升西降), saying that the power of the Western world was in decline and their COVID-19 response was an example of this, and that China was entering a period of opportunity because of this.[262] Xi has frequently alluded to "community with a shared future for mankind," which Chinese diplomats have said doesn't imply an intention to change the international order,[263] but which foreign observers say China wants a new order that puts it more at the centre.[264] Under Xi, China has, along with Russia, also focused on increasing relations with the Global South in order to blunt the effect of international sanctions.[265]

Xi has put an emphasis on increasing China's "international discourse power" (国际话语权) to create a more favorable global opinion of China in the world.[266] In this pursuit, Xi has emphasised the need to "tell China's story well" (讲好中国故事), meaning expanding China's external propaganda (外宣) and communications.[267] Xi has expanded the focus and scope of the united front, which aims to consolidate support for CCP in non-CCP elements both inside and outside China, and has accordingly expanded the United Front Work Department.[268] Xi has unveiled the Global Development Initiative (GDI),[269] the Global Security Initiative (GSI),[270] and the Global Civilisation Initiative (GCI), in 2021, 2022 and 2023, respectively, aiming to increase China's influence in the international order.[271]

During the Xi administration, China seeks to shape international norms and rules in emerging policy areas where China has an advantage as an early participant.[272]: 188 Xi describes such areas as "new frontiers," and they include policy areas such as space, deep sea, polar regions, the Internet, nuclear safety, anticorruption, and climate change.[272]: 188

National security

Xi has devoted a large amount of work towards national security, calling for a "holistic national security architecture" that encompasses "all aspects of the work of the party and the country."[273] He introduced the holistic security concept in 2014, which he defined as taking "the security of the people as compass, political security as its roots, economic security as its pillar, military security, cultural security, and cultural security as its protections, and that relies on the promotion of international security."[274]: 3 During a private talk with U.S. president Obama and vice president Biden, he said that China had been a target of "colour revolutions," foreshadowing his focus on national security.[275] Since its creation by Xi, the National Security Commission has established local security committees, focusing on dissent.[275] In the name of national security, Xi's government has passed numerous laws including a counterespionage law in 2014,[276] national security[277] and a counterterrorism law in 2015,[278] a cybersecurity law[279] and a law restricting foreign NGOs in 2016,[280] a national intelligence law in 2017,[281] and a data security law in 2021.[282] Under Xi, China's mass surveillance network has dramatically grown, with comprehensive profiles being built for each citizen.[283]

Hong Kong

During his leadership, Xi has supported and pursued a greater political and economic integration of Hong Kong to mainland China, including through projects such as the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge.[284] He has pushed for the Greater Bay Area project, which aims to integrate Hong Kong, Macau, and nine other cities in Guangdong.[285][284] Xi's integration efforts have led to decreased freedoms and the weakening of Hong Kong's distinct identity from mainland China.[285][286] Many of the views held by the central government and eventually implemented in Hong Kong were outlined in a white paper published by the State Council in 2014 named The Practice of the 'One Country, Two Systems' Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, which outlined that the China's central government has "comprehensive jurisdiction" over Hong Kong.[287] Under Xi, the Chinese government also declared the Sino-British Joint Declaration to be legally void.[287]

In August 2014, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC) made a decision allowing universal suffrage for the 2017 election of the chief executive of Hong Kong, but also requiring the candidates to "love the country, and love Hong Kong," as well as other measures that ensured the Chinese leadership would be the ultimate decision-maker on the selection, leading to protests,[288] and the eventual rejection of the reform bill in the Legislative Council due to a walk-out by the pro-Beijing camp to delay to vote.[289] In the 2017 chief executive election, Carrie Lam was victorious, reportedly with the endorsement of the CCP Politburo.[290]

Xi has supported the Hong Kong Government and Carrie Lam against the protesters in the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests, which broke out after a proposed bill that would allow extraditions to China.[291] He has defended the Hong Kong police's use of force, saying that "We sternly support the Hong Kong police to take forceful actions in enforcing the law, and the Hong Kong judiciary to punish in accordance with the law those who have committed violent crimes."[292] While visiting Macau on 20 December 2019 as part of the 20th anniversary of its return to China, Xi warned of foreign forces interfering in Hong Kong and Macau,[293] while also hinting that Macau could be a model for Hong Kong to follow.[294]

In 2020, the NPCSC passed a national security law in Hong Kong that dramatically expanded government clampdown over the opposition in the city; amongst the measures were the dramatic restriction on political opposition and the creation of a central government office outside Hong Kong jurisdiction to oversee the enforcement of the law.[287] This was seen as the culmination of a long-term project under Xi to further closely integrate Hong Kong with the mainland.[287] Xi visited Hong Kong as president in 2017 and 2022, in the 20th and 25th anniversary of the handover of Hong Kong respectively.[295] In his 2022 visit, he swore in John Lee as chief executive, a former police officer that was backed by the Chinese government to expand control over the city.[296][297]

Taiwan

In November 2015, Xi met with Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou, which marked the first time the political leaders of both sides of the Taiwan Strait have met since the end of the Chinese Civil War in mainland China in 1950.[298] Xi said that China and Taiwan are "one family" that cannot be pulled apart.[299] However, the relations started deteriorating after Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) won the presidential elections in 2016.[300]

In the 19th Party Congress held in 2017, Xi reaffirmed six of the nine principles that had been affirmed continuously since the 16th Party Congress in 2002, with the notable exception of "Placing hopes on the Taiwan people as a force to help bring about unification".[301] According to the Brookings Institution, Xi used stronger language on potential Taiwan independence than his predecessors towards previous DPP governments in Taiwan. Xi said that "we will never allow any person, any organisation, or any political party to split any part of the Chinese territory from China at any time at any form."[301]

In January 2019, Xi Jinping called on Taiwan to reject its formal independence from China, saying: "We make no promise to renounce the use of force and reserve the option of taking all necessary means." Those options, he said, could be used against "external interference". Xi also said that they "are willing to create broad space for peaceful reunification, but will leave no room for any form of separatist activities."[302][303] President Tsai responded to the speech by saying Taiwan would not accept a one country, two systems arrangement with the mainland, while stressing the need for all cross-strait negotiations to be on a government-to-government basis.[304]

Human rights

According to the Human Rights Watch, Xi has "started a broad and sustained offensive on human rights" since he became leader in 2012.[305] The HRW also said that repression in China is "at its worst level since the Tiananmen Square massacre."[306] Since taking power, Xi has cracked down on grassroots activism, with hundreds being detained.[307] He presided over the 709 crackdown on 9 July 2015, which saw more than 200 lawyers, legal assistants and human rights activists being detained.[308] His term has seen the arrest and imprisonment of activists such as Xu Zhiyong, as well as numerous others who identified with the New Citizens' Movement. Prominent legal activist Pu Zhiqiang of the Weiquan movement was also arrested and detained.[309]

In 2017, the local government of the Jiangxi province told Christians to replace their pictures of Jesus with Xi Jinping as part of a general campaign on unofficial churches in the country.[310][311][312] According to local social media, officials "transformed them from believing in religion to believing in the party."[310] According to activists, "Xi is waging the most severe systematic suppression of Christianity in the country since religious freedom was written into the Chinese constitution in 1982," and according to pastors and a group that monitors religion in China, has involved "destroying crosses, burning bibles, shutting churches and ordering followers to sign papers renouncing their faith."[313]

Under Xi, the CCP has embraced assimilationist policies towards ethnic minorities, scaling back affirmative action in the country by 2019,[314] and scrapping a wording in October 2021 that guaranteed the rights of minority children to be educated in their native language, replacing it with one that emphasized teaching the national language.[315] In 2020, Chen Xiaojiang was appointed as head of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission, the first Han Chinese head of the body since 1954.[316] On 24 June 2022, Pan Yue, another Han Chinese, became the head of the commission, with him reportedly holding assimilationist policies toward ethnic minorities.[317] Xi outlined his official views relations between the majority Han Chinese and ethnic minorities by saying "[n]either Han chauvinism nor local ethnic chauvinism is conducive to the development of a community for the Chinese nation."[318]

Xinjiang

Following several terrorist attacks in Xinjiang in 2013 and 2014, the CCP leaders held a secret meeting to find a solution to the attacks,[319] leading to Xi to launch the Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism in 2014, which involved mass detention, and surveillance of ethnic Uyghurs there.[320][321] The campaign included the detainment of 1.8 million people in internment camps, mostly Uyghurs but also including other ethnic and religious minorities, by 2020,[319] and a birth suppression campaign that led to a large drop in the Uyghur birth rate by 2019.[322] Human rights groups and former inmates have described the camps as "concentration camps," where Uyghurs and other minorities have been forcibly assimilated into China's majority ethnic Han society.[323] This program has been called a genocide by western observers, while a report by the UN Human Rights Office said they may amount to crimes against humanity.[324][325]

Internal Chinese government documents leaked to the press in November 2019 showed that Xi personally ordered a security crackdown in Xinjiang, saying that the party must show "absolutely no mercy" and that officials use all the "weapons of the people's democratic dictatorship" to suppress those "infected with the virus of extremism."[321][326] The papers also showed that Xi repeatedly discussed about Islamic extremism in his speeches, likening it to a "virus" or a "drug" that could be only addressed by "a period of painful, interventionary treatment."[321] However, he also warned against the discrimination against Uyghurs and rejected proposals to eradicate Islam in China, calling that kind of viewpoint "biased, even wrong."[321] Xi's exact role in the building of internment camps has not been publicly reported, though he's widely believed to be behind them and his words have been the source for major justifications in the crackdown in Xinjiang.[327][328]

During a four-day visit to Xinjiang in July 2022, Xi urged local officials to always listen to the people's voices[329] and to do more in preservation of ethnic minority culture.[330] He also inspected the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps and praised its "great progress" in reform and development.[331] During another visit to Xinjiang in August 2023, Xi said in a speech that the region was "no longer a remote area" and should open up more for tourism to attract domestic and foreign visitors.[332][333]

COVID-19 pandemic

On 20 January 2020, Xi commented for the first time on the emerging COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, and ordered "efforts to curb the spread" of the virus.[334] He gave premier Li Keqiang some responsibility over the COVID-19 response, in what has been suggested by The Wall Street Journal was an attempt to potentially insulate himself from criticism if the response failed.[335] The government initially responded to the pandemic with a lockdown and censorship, with the initial response causing widespread backlash within China.[336] He met with Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the director-general of the World Health Organization (WHO), on 28 January.[337] Der Spiegel reported that in January 2020 Xi pressured Tedros Adhanom to hold off on issuing a global warning about the outbreak of COVID-19 and hold back information on human-to-human transmission of the virus, allegations denied by the WHO.[338] On 5 February, Xi met with Cambodian prime minister Hun Sen in Beijing, the first foreign leader allowed into China since the outbreak.[337] After the COVID-19 outbreak got under control in Wuhan, Xi visited the city on 10 March.[339]

After getting the outbreak in Wuhan under control, Xi has favoured what has officially been termed "dynamic zero-COVID policy"[340] that aims to control and suppress the virus as much as possible within the country's borders. This has involved local lockdowns and mass-testing.[341] While initially credited for China's suppression of the COVID-19 outbreak, the policy was later criticized by foreign and some domestic observers for being out of touch with the rest of the world and taking a heavy toll on the economy.[341] This approach has especially come under criticism during a 2022 lockdown on Shanghai, which forced millions to their homes and damaged the city's economy,[342] denting the image of Li Qiang, close Xi ally and Party secretary of the city.[343] Conversely, Xi has said that the policy was designed to protect people's life safety.[344] On 23 July 2022, the National Health Commission reported that Xi and other top leaders have taken the local COVID-19 vaccines.[345]

At the 20th CCP Congress, Xi confirmed the continuation of the zero-COVID policy,[346] stating he would "unswervingly" carry out "dynamic zero-COVID" and promising to "resolutely win the battle,"[347] though China started a limited easing of the policies in the following weeks.[348] In November 2022, protests broke out against China's COVID-19 policies, with a fire in a high-rise apartment building in Ürümqi being the trigger.[349] The protests were held in multiple major cities, with some of the protesters demanding the end of Xi's and the CCP's rule.[349] The protests were mostly suppressed by December,[349] though the government further eased COVID-19 restrictions in the time since.[350] On 7 December 2022, China announced large-scale changes to its COVID-19 policy, including allowing quarantine at home for mild infections, reducing of PCR testing, and decreasing the power of local officials to implement lockdowns.[351]

Environmental policy

Xi identifies environmental protection as one of China's five major priorities for national progress.[352]: 164

In September 2020, Xi announced that China will "strengthen its 2030 climate target (NDC), peak emissions before 2030 and aim to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060."[353] If accomplished, this would lower the expected rise in global temperature by 0.2–0.3 °C – "the biggest single reduction ever estimated by the Climate Action Tracker."[353] Xi mentioned the link between the COVID-19 pandemic and nature destruction as one of the reasons for the decision, saying that "Humankind can no longer afford to ignore the repeated warnings of nature."[354] On 27 September, Chinese scientists presented a detailed plan how to achieve the target.[355] In September 2021, Xi announced that China will not build "coal-fired power projects abroad, which was said to be potentially "pivotal" in reducing emissions. The Belt and Road Initiative did not include financing such projects already in the first half of 2021.[356]

Xi has popularized a metaphor of "two mountains" to emphasize the importance of environmental protection.[352]: 164 The concept is that a mountain made of gold or silver is valuable, but green mountains with clear waters are more valuable.[352]: 164 The slogan's meaning is that economic development priorities must also provide for economic protection.[352]: 164

Xi Jinping did not attend COP26 personally. However, a Chinese delegation led by climate change envoy Xie Zhenhua did attend.[357][358] During the conference, the United States and China agreed on a framework to reduce GHG emission by co-operating on different measures.[359]

Governance style

Known as a very secretive leader, little is known publicly about how Xi makes political decisions, or how he came to power.[360][361] Xi's speeches generally get released months or years after they are made.[360] Xi has also never given a press conference since becoming paramount leader, except in rare joint press conferences with foreign leaders.[360][362] The Wall Street Journal reported that Xi prefers micromanaging in governance, in contrast to previous leaders such as Hu Jintao who left details of major policies to lower-ranking officials.[120] Reportedly, ministerial officials try to get Xi's attention in various ways, with some creating slide shows and audio reports. The Wall Street Journal also reported that Xi created a performance-review system in 2018 to give evaluations on officials on various measures, including loyalty.[120] According to The Economist, Xi's orders have generally been vague, leaving lower level officials to interpret his words.[327] Chinese state media Xinhua News Agency said that Xi "personally reviews every draft of major policy documents" and "all reports submitted to him, no matter how late in the evening, were returned with instructions the following morning."[363] With regard to behavior of Communist Party members, Xi emphasizes the "Two Musts" (members must not be arrogant or rash and must keep their hard-working spirit) and the "Six Nos" (members must say no to formalism, bureaucracy, gift-giving, luxurious birthday celebrations, hedonism, and extravagance).[189]: 52 Xi called for officials to practice self-criticism which, according to observers, is in order to appear less corrupt and more popular among the people.[364][365][366] According to Japanese diplomat Hideo Tarumi, who served as the Japanese ambassador to China, Xi has engaged in heavy process of centralization in order to maintain the legitimacy of the rule of Chinese Communist Party.[367]

Political positions

A party and its authority rests on winning the hearts and minds of the people. What the public opposes and hates, we must address and resolve.

[M]aterial and cultural needs grown; demands for democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security, and a better environment are also increasing each day.

Chinese Dream

Xi and CCP ideologues coined the phrase "Chinese Dream" to describe his overarching plans for China as its leader. Xi first used the phrase during a high-profile visit to the National Museum of China on 29 November 2012, where he and his Standing Committee colleagues were attending a "national revival" exhibition. Since then, the phrase has become the signature political slogan of the Xi era.[369][370] The origin of the term "Chinese Dream" is unclear. While the phrase has been used before by journalists and scholars,[371] some publications have posited the term likely drew its inspiration from the concept of the American Dream.[372] The Economist noted the abstract and seemingly accessible nature of the concept with no specific overarching policy stipulations may be a deliberate departure from the jargon-heavy ideologies of his predecessors.[373] Xi has linked the "Chinese Dream" with the phrase "great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation."[374][d]

Culture

In recent years, top political leaders of the CCP such as Xi have overseen the rehabilitation of ancient Chinese philosophical figures like Han Fei into the mainstream of Chinese thought alongside Confucianism. At a meeting with other officials in 2013, he quoted Confucius, saying "he who rules by virtue is like the Pole Star, it maintains its place, and the multitude of stars pay homage." While visiting Shandong, the birthplace of Confucius, in November, he told scholars that the Western world was "suffering a crisis of confidence" and that the CCP has been "the loyal inheritor and promoter of China's outstanding traditional culture."[375]

According to several analysts, Xi's leadership has been characterised by a resurgence of the ancient political philosophy Legalism.[376][377][378] Han Fei gained new prominence with favourable citations; one sentence of Han Fei's that Xi quoted appeared thousands of times in official Chinese media at the local, provincial, and national levels.[378] Xi has additionally supported the Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming, telling local leaders to promote him.[379]

On 15 October 2014, Xi Jinping emulated the Yan'an Talks with his 'Speech at the Forum on Literature and Art.'[380]: 15 Consistent with Mao's view in the Yan'an Talks, Xi believes works of art should be judged by political criteria.[380]: 16 In 2021, Xi quoted the Yan'an Talks during the opening ceremony of the 11th National Congress of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles and the 10th National Congress of the Chinese Writers Association.[189]: 174 According to Xi, art should be judged by political criteria.[380]: 16 This view rejects the concept of art-for-art's-sake and contends that art should serve the goal of national rejuvenation.[380]: 16 Xi criticizes market-driven art which he deems sensationalist, particularly works which "exaggerate society's dark side" for profit.[380]: 16 He ordered the arts industry to "tell China's stories and spread Chinese voices to strengthen the country's international communication capacity."[381]