Johann Gottfried Herder

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2024) |

Johann Gottfried Herder | |

|---|---|

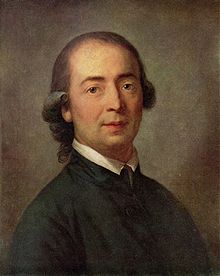

Herder, 1785 | |

| Born | 25 August 1744 Mohrungen, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 18 December 1803 (aged 59) Weimar, Saxe-Weimar, Holy Roman Empire |

| Alma mater | University of Königsberg |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Academic advisors | Immanuel Kant |

Johann Gottfried von Herder (/ˈhɜːrdər/ HUR-dər; German: [ˈjoːhan ˈɡɔtfʁiːt ˈhɛʁdɐ];[15][16][17] 25 August 1744 – 18 December 1803) was a Prussian philosopher, theologian, pastor, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, Sturm und Drang, and Weimar Classicism. He was a Romantic philosopher and poet who argued that true German culture was to be discovered among the common people (das Volk). He also stated that it was through folk songs, folk poetry, and folk dances that the true spirit of the nation (der Volksgeist) was popularized. He is credited with establishing or advancing a number of important disciplines: hermeneutics, linguistics, anthropology, and "a secular philosophy of history."[18]

Biography

[edit]Born in Mohrungen (now Morąg, Poland) in the Kingdom of Prussia, his parents were teacher Gottfried Herder (1706–1763) and his wife Anna Elizabeth Herder, nee Peltz (1717–1772) grew up in a poor household, educating himself from his father's Bible and songbook. In 1762, as a youth of 17, he enrolled at the University of Königsberg, about 60 miles (100 km) north of Mohrungen, where he became a student of Immanuel Kant. At the same time, Herder became an intellectual protégé of Johann Georg Hamann, a Königsberg philosopher who disputed the claims of pure secular reason.

Hamann's influence led Herder to confess to his wife later in life that "I have too little reason and too much idiosyncrasy",[19] yet Herder can justly claim to have founded a new school of German political thought. Although himself an unsociable person, Herder influenced his contemporaries greatly. One friend wrote to him in 1785, hailing his works as "inspired by God." A varied field of theorists were later to find inspiration in Herder's tantalizingly incomplete ideas.

In 1764, now a Lutheran pastor, Herder went to Riga to teach. It was during this period that he produced his first major works, which were literary criticism. In 1769 Herder traveled by ship to the French port of Nantes and continued on to Paris. This resulted in both an account of his travels as well as a shift of his own self-conception as an author. By 1770 Herder went to Strasbourg, where he met the young Goethe. This event proved to be a key juncture in the history of German literature, as Goethe was inspired by Herder's literary criticism to develop his own style. This can be seen as the beginning of the Sturm und Drang movement. In 1771 Herder took a position as head pastor and court preacher at Bückeburg under William, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe.

By the mid-1770s, Goethe was a well-known author, and used his influence at the court of Weimar to secure Herder a position as General Superintendent. Herder moved there in 1776, where his outlook shifted again towards classicism.

On 2 May 1773 Herder married Maria Karoline Flachsland (1750–1809) in Darmstadt. His son Gottfried (1774–1806) was born in Bückeburg. His second son August (1776–1838) was also born in Bückeburg. His third son Wilhelm Ludwig Ernst was born 1778. His fourth son Karl Emil Adelbert (1779–1857) was born in Weimar. In 1781 his daughter Luise (1781–1860) was born, also in Weimar. His fifth son Emil Ernst Gottfried (1783–1855). In 1790 his sixth son Rinaldo Gottfried was born.

Towards the end of his career, Herder endorsed the French Revolution, which earned him the enmity of many of his colleagues. At the same time, he and Goethe experienced a personal split. His unpopular attacks on Kantian philosophy were another reason for his isolation in later years.[20]

In 1802 Herder was ennobled by the Elector-Prince of Bavaria, which added the prefix "von" to his last name. He died in Weimar in 1803 at age 59.

Works and ideas

[edit]Herder was influenced by his academic advisor Immanuel Kant, as well as seventeenth-century philosophers Spinoza and Leibniz.[21] In turn, he influenced Hegel, Nietzsche, Goethe, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, John Stuart Mill, Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel, Wilhelm von Humboldt,[22][23] Franz Boas,[24] and Walter Rauschenbusch[25] among others.

In 1772, Herder published Treatise on the Origin of Language and went further in this promotion of language than his earlier anti-French injunction to "spew out the ugly slime of the Seine. Speak German, O You German". Herder now had established the foundations of comparative philology within the new currents of political outlook.

Herder wrote an important essay on Shakespeare and Auszug aus einem Briefwechsel über Ossian und die Lieder alter Völker (Extract from a correspondence about Ossian and the Songs of Ancient Peoples) published in 1773 in a manifesto along with contributions by Goethe and Justus Möser. Herder wrote that "A poet is the creator of the nation around him, he gives them a world to see and has their souls in his hand to lead them to that world." To him such poetry had its greatest purity and power in nations before they became civilised, as shown in the Old Testament, the Edda, and Homer, and he tried to find such virtues in ancient German folk songs and Norse poetry and mythology. Herder – most pronouncedly after Georg Forster's 1791 translation of the Sanskrit play Shakuntala – was influenced by the religious imagery of Hinduism and Indian literature, which he saw in a positive light, writing several essays on the topic and the preface to the 1803 edition of Shakuntala.[26][27]

After becoming General Superintendent in 1776, Herder's philosophy shifted again towards classicism, and he produced works such as his unfinished Outline of a Philosophical History of Humanity, which largely originated the school of historical thought. Herder's philosophy was of a deeply subjective turn, stressing influence by physical and historical circumstance upon human development, stressing that "one must go into the age, into the region, into the whole history, and feel one's way into everything". The historian should be the "regenerated contemporary" of the past, and history a science as "instrument of the most genuine patriotic spirit".

Germans did not have a nation-state until the nineteenth century. Those who spoke Germanic languages lived in politically unconnected lands and groups. Herder was among the first German intellectuals to craft a foundation for German cultural unification and German national consciousness based mostly on German language and literature. While rationality was the prime value of Enlightenment philosophers, Herder's appeal to sentiment places him within German Romantiscm.[28] He gave Germans new pride in their origins, modifying that dominance of regard allotted to Greek art (Greek revival) extolled among others by Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing.[citation needed] He remarked that he would have wished to be born in the Middle Ages and mused whether "the times of the Swabian emperors" did not "deserve to be set forth in their true light in accordance with the German mode of thought?". Herder equated the German with the Gothic and favored Dürer and everything Gothic.[citation needed] As with the sphere of art, he also proclaimed a national message within the sphere of language. He topped the line of German authors emanating from Martin Opitz, who had written his Aristarchus, sive de contemptu linguae Teutonicae in latin in 1617, urging Germans to glory in their hitherto despised language. Herder's extensive collections of folk-poetry began a great craze in Germany for that neglected topic.

Herder was one of the first to argue that language contributes to shaping the frameworks and the patterns with which each linguistic community thinks and feels. For Herder, language is "the organ of thought." This has often been misinterpreted, however. Neither Herder nor the great philosopher of language, Wilhelm von Humboldt, argue that language (written or oral) determines thought. Rather, language was the appropriation of the outer world within the human mind by means of distinguishing marks (merkmale). In positing his arguments, Herder reformulated an example from works by Moses Mendelssohn and Thomas Abbt. In his conjectural narrative of human origins, Herder argued that, although linguistic morphemes and logographs did not determine thought, the first humans perceived sheep and their bleating, or subjects and corresponding Merkmale, as one and the same. That is, for these conjectured ancestors, the sheep were the bleating, and vice-versa. Hence, prelinguistic thought did not figure largely in Herderian conjectural narratives. Herder even moved beyond his narrative of human origins to contend that if active reflection (besonnenheit) and language persisted in human consciousness, then human impulses to signify were immanent in the pasts, presents, and futures of humanity. Avi Lifschitz subsequently reframed Herder's "the organ of thought" quotation: "Herder's equation of word and idea, of language and cognition, prompted a further attack on any attribution of the first words to the imitation of natural sounds, to the physiology of the vocal organs, or to social convention… [Herder argued] for the linguistic character of our cognition but also for the cognitive nature of human language. One could not think without language, as various Enlightenment thinkers argued, but at the same time one could not properly speak without perceiving the world in a uniquely human way… man would not be himself without language and active reflection, while language deserved its name only as a cognitive aspect of the entire human being." In response to criticism of these contentions, Herder resisted descriptions of his findings as "conjectural" pasts, casting his arguments for a dearth of cognition in humans and "the problem of the origin of language as a synchronic issue rather than a diachronic one."[29]

And in this sense, when Humboldt argues that all thinking is thinking in language, he is perpetuating the Herderian tradition. Herder additionally advanced select notions of myriad "authentic" conceptions of Völk and the unity of the individual and natural law, which became fodder for his self-proclaimed twentieth-century disciples. Herderian ideas continue to influence thinkers, linguists and anthropologists, and they have often been considered central to the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and Franz Boas' coalescence of comparative linguistics and historical particularism with a neo-Kantian/Herderian four-field approach to the study of all cultures, as well as, more recently, anthropological studies by Dell Hymes. Herder's focus upon language and cultural traditions as the ties that create a "nation"[30] extended to include folklore, dance, music and art, and inspired Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in their collection of German folk tales. Arguably, the greatest inheritor of Herder's linguistic philosophy was Wilhelm von Humboldt. Humboldt's great contribution lay in developing Herder's idea that language is "the organ of thought" into his own belief that languages were specific worldviews (Weltansichten), as Jürgen Trabant argues in the Wilhelm von Humboldt lectures on the Rouen Ethnolinguistics Project website.

Herder attached exceptional importance to the concept of nationality and of patriotism – "he that has lost his patriotic spirit has lost himself and the whole worlds about himself", whilst teaching that "in a certain sense every human perfection is national". Herder carried folk theory to an extreme by maintaining that "there is only one class in the state, the Volk, (not the rabble), and the king belongs to this class as well as the peasant". Explanation that the Volk was not the rabble was a novel conception in this era, and with Herder can be seen the emergence of "the people" as the basis for the emergence of a classless but hierarchical national body.

The nation, however, was individual and separate, distinguished, to Herder, by climate, education, foreign intercourse, tradition and heredity. Providence he praised for having "wonderfully separated nationalities not only by woods and mountains, seas and deserts, rivers and climates, but more particularly by languages, inclinations and characters". Herder praised the tribal outlook writing that "the savage who loves himself, his wife and child with quiet joy and glows with limited activity of his tribe as for his own life is in my opinion a more real being than that cultivated shadow who is enraptured with the shadow of the whole species", isolated since "each nationality contains its centre of happiness within itself, as a bullet the centre of gravity". With no need for comparison since "every nation bears in itself the standard of its perfection, totally independent of all comparison with that of others" for "do not nationalities differ in everything, in poetry, in appearance, in tastes, in usages, customs and languages? Must not religion which partakes of these also differ among the nationalities?"

Following a trip to Ukraine, Herder wrote a prediction in his diary (Journal meiner Reise im Jahre 1769) that Slavic nations would one day be the real power in Europe, as the western Europeans would reject Christianity and rot away, while the eastern European nations would retain their religion and their idealism, and would this way become the power in Europe. More specifically, he praised Ukraine's "beautiful skies, blithe temperament, musical talent, bountiful soil, etc.… someday will awaken there a cultured nation whose influence will spread… throughout the world." One of his related predictions was that the Hungarian nation would disappear and become assimilated by surrounding Slavic peoples; this prophecy caused considerable uproar in Hungary and is widely cited to this day.[31]

Germany and the Enlightenment

[edit]This question was further developed by Herder's lament that Martin Luther did not establish a national church, and his doubt whether Germany did not buy Christianity at too high a price, that of true nationality. Herder's patriotism bordered at times upon national pantheism, demanding of territorial unity as "He is deserving of glory and gratitude who seeks to promote the unity of the territories of Germany through writings, manufacture, and institutions" and sounding an even deeper call:

But now! Again I cry, my German brethren! But now! The remains of all genuine folk-thought is rolling into the abyss of oblivion with a last and accelerated impetus. For the last century we have been ashamed of everything that concerns the fatherland.

In his Ideas upon Philosophy and the History of Mankind he wrote: "Compare England with Germany: the English are Germans, and even in the latest times the Germans have led the way for the English in the greatest things."

Herder, who hated absolutism and Prussian nationalism, but who was imbued with the spirit of the whole German Volk, yet as a historical theorist turned away from the ideas of the eighteenth century. Seeking to reconcile his thought with this earlier age, Herder sought to harmonize his conception of sentiment with reasoning, whereby all knowledge is implicit in the soul; the most elementary stage is the sensuous and intuitive perception which by development can become self-conscious and rational. To Herder, this development is the harmonizing of primitive and derivative truth, of experience and intelligence, feeling and reasoning.

Herder is the first in a long line of Germans preoccupied with this harmony. This search is itself the key to the understanding of many German theories of the time; however Herder understood and feared the extremes to which his folk-theory could tend, and so issued specific warnings. He argued that Jews in Germany should enjoy the full rights and obligations of Germans, and that the non-Jews of the world owed a debt to Jews for centuries of abuse, and that this debt could be discharged only by actively assisting those Jews who wished to do so to regain political sovereignty in their ancient homeland of Israel.[32] Herder refused to adhere to a rigid racial theory, writing that "notwithstanding the varieties of the human form, there is but one and the same species of man throughout the whole earth".

He also announced that "national glory is a deceiving seducer. When it reaches a certain height, it clasps the head with an iron band. The enclosed sees nothing in the mist but his own picture; he is susceptible to no foreign impressions."

The passage of time was to demonstrate that while many Germans were to find influence in Herder's convictions and influence, fewer were to note his qualifying stipulations.

Herder had emphasised that his conception of the nation encouraged democracy and the free self-expression of a people's identity. He proclaimed support for the French Revolution, a position which did not endear him to royalty. He also differed with Kant's philosophy for not placing reasoning within the context of language. Herder did not think that reason itself could be criticized, as it did not exist except as the process of reasoning. This process was dependent on language.[33] He also turned away from the Sturm und Drang movement to go back to the poems of Shakespeare and Homer.

To promote his concept of the Volk, he published letters and collected folk songs. These latter were published in 1773 as Voices of the Peoples in Their Songs (Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern). The poets Achim von Arnim and Clemens von Brentano later used Stimmen der Völker as samples for The Boy's Magic Horn (Des Knaben Wunderhorn).

Herder also fostered the ideal of a person's individuality. Although he had from an early period championed the individuality of cultures – for example, in his This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774), he also championed the individuality of persons within a culture; for example, in his On Thomas Abbt's Writings (1768) and On the Cognition and Sensation of the Human Soul (1778).

In On Thomas Abbt's Writings, Herder stated that "a human soul is an individual in the realm of minds: it senses in accordance with an individual formation, and thinks in accordance with the strength of its mental organs. ... My long allegory has succeeded if it achieves the representation of the mind of a human being as an individual phenomenon, as a rarity which deserves to occupy our eyes."[34]

Evolution

[edit]Herder has been described as a proto-evolutionary thinker by some science historians, although this has been disputed by others.[35][36][37] Concerning the history of life on earth, Herder proposed naturalistic and metaphysical (religious) ideas that are difficult to distinguish and interpret.[36] He was known for proposing a great chain of being.[37]

In his book From the Greeks to Darwin, Henry Fairfield Osborn wrote that "in a general way he upholds the doctrine of the transformation of the lower and higher forms of life, of a continuous transformation from lower to higher types, and of the law of Perfectibility."[38] However, biographer Wulf Köpke disagreed, noting that "biological evolution from animals to the human species was outside of his thinking, which was still influenced by the idea of divine creation."[39]

Bibliography

[edit]- Song to Cyrus, the Grandson of Astyages (1762)

- Essay on Being (1763–64)[40]

- On Diligence in Several Learned Languages (1764)

- Treatise on the Ode (1764)[41]

- How Philosophy can become more Universal and Useful for the Benefit of the People (1765)[42]

- Fragments on Recent German Literature (1767–68)[43]

- On Thomas Abbt's Writings (1768)

- Critical Forests, or Reflections on the Science and Art of the Beautiful (1769–)

- Gott – einige Gespräche über Spinoza's System nebst Shaftesbury's Naturhymnus (Gotha: Karl Wilhelm Ettinger, 1787)

- Journal of my Voyage in the Year 1769 (first published 1846)

- Treatise on the Origin of Language (1772)[44]

- Selection from correspondence on Ossian and the songs of ancient peoples (1773) See also: James Macpherson (1736–1796).

- Of German Character and Art (with Goethe, manifesto of the Sturm und Drang) (1773)

- This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774)[42]

- Oldest Document of the Human Race (1774–76)

- "Essay on Ulrich von Hutten" ["Nachricht von Ulrich von Hutten"] (1776)[45]

- On the Resemblance of Medieval English and German Poetry (1777)

- Sculpture: Some Observations on Shape and Form from Pygmalion's Creative Dream (1778)

- On the Cognition and Sensation of the Human Soul (1778)

- On the Effect of Poetic Art on the Ethics of Peoples in Ancient and Modern Times (1778)

- Folk Songs (1778–79; second ed. of 1807 titled The Voices of Peoples in Songs)

- On the Influence of the Government on the Sciences and the Sciences on the Government (Dissertation on the Reciprocal Influence of Government and the Sciences) (1780)

- Letters Concerning the Study of Theology (1780–81)

- On the Influence of the Beautiful in the Higher Sciences (1781)

- On the Spirit of Hebrew Poetry. An Instruction for Lovers of the Same and the Oldest History of the Human Spirit (1782–83)

- God. Some Conversations (1787)

- Oriental Dialogues 1787

- Ideas on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind (1784–91)

- Scattered Leaves (1785–97)

- Letters for the Advancement of Humanity (1791–97 or 1793–97? (various drafts))

- Thoughts on Some Brahmins (1792)[26]

- Zerstreute Blätter (1792)[26]

- Christian Writings (5 vols.) (1794–98)

- Terpsichore (1795–96) A translation and commentary of the Latin poet Jakob Balde.

- On the Son of God and Saviour of the World, according to the Gospel of John (1797)

- Persepolisian Letters (1798). Fragments on Persian architecture, history and religion.

- Luther's Catechism, with a catechetical instruction for the use of schools (1798)

- Understanding and Experience. A Metacritique of the Critique of Pure Reason. Part I. (Part II, Reason and Language.) (1799)

- Calligone (1800)

- Adrastea: Events and Characters of the 18th Century (6 vols.) (1801–03)[46][47]

- The Cid (1805; a free translation of the Spanish epic Cantar de Mio Cid)

Works in English

[edit]- Herder's Essay on Being. A Translation and Critical Approaches. Edited and translated by John K. Noyes. Rochester: Camden House 2018. Herder's early essay on metaphysics, translated with a series of critical commentaries.

- Song Loves the Masses: Herder on Music and Nationalism. Edited and translated by Philip Vilas Bohlman (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017). Collected writings on music, from Volkslieder to sacred song.

- Selected Writings on Aesthetics. Edited and translated by Gregory Moore. Princeton U.P. 2006. pp. x + 455. ISBN 978-0691115955. Edition makes many of Herder's writings on aesthetics available in English for the first time.

- Another Philosophy of History and Selected Political Writings, eds. Ioannis D. Evrigenis and Daniel Pellerin (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2004). A translation of Auch eine Philosophie and other works.

- Philosophical Writings, ed. Michael N. Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002). The most important philosophical works of the early Herder available in English, including an unabridged version of the Treatise on the Origin of Language and This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Mankind.

- Sculpture: Some Observations on Shape and Form from Pygmalion's Creative Dream, ed. Jason Gaiger (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). Herder's Plastik.

- Selected Early Works, eds. Ernest A. Menze and Karl Menges (University Park: The Pennsylvania State Univ. Press, 1992). Partial translation of the important text Über die neuere deutsche Litteratur.

- On World History, eds. Hans Adler and Ernest A. Menze (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1997). Short excerpts on history from various texts.

- J. G. Herder on Social & Political Culture (Cambridge Studies in the History and Theory of Politics), ed. F. M. Barnard (Cambridge University Press, 2010 (originally published in 1969)) ISBN 978-0-521-13381-4 Selected texts: 1. Journal of my voyage in the year 1769; 2. Essay on the origin of language; 3. Yet another philosophy of history; 4. Dissertation on the reciprocal influence of government and the sciences; 5. Ideas for a philosophy of the history of mankind.

- Herder: Philosophical Writings, ed. Desmond M. Clarke and Michael N. Forster (Cambridge University Press, 2007), ISBN 978-0-521-79088-8. Contents: Part I. General Philosophical Program: 1. How philosophy can become more universal and useful for the benefit of the people (1765); Part II. Philosophy of Language: 2. Fragments on recent German literature (1767–68); 3. Treatise on the origin of language (1772); Part III. Philosophy of Mind: 4. On Thomas Abbt's writings (1768); 5. On cognition and sensation, the two main forces of the human soul; 6. On the cognition and sensation, the two main forces of the human soul (1775); Part IV. Philosophy of History: 7. On the change of taste (1766); 8. Older critical forestlet (1767/8); 9. This too a philosophy of history for the formation of humanity (1774); Part V. Political Philosophy: 10. Letters concerning the progress of humanity (1792); 11. Letters for the advancement of humanity (1793–97).

- Herder on Nationality, Humanity, and History, F. M. Barnard. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003.) ISBN 978-0-7735-2519-1.

- Herder's Social and Political Thought: From Enlightenment to Nationalism, F. M. Barnard, Oxford, Publisher: Clarendon Press, 1967.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Isaiah Berlin, Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder, London and Princeton, 2000.

- ^ Kerrigan, William Thomas (1997), "Young America": Romantic Nationalism in Literature and Politics, 1843–1861, University of Michigan, 1997, p. 150.

- ^ Royal J. Schmidt, "Cultural Nationalism in Herder," Journal of the History of Ideas 17(3) (June 1956), pp. 407–417.

- ^ Gregory Claeys (ed.), Encyclopedia of Modern Political Thought, Routledge, 2004, "Herder, Johann Gottfried": "Herder is an anticolonialist cosmopolitan precisely because he is a nationalist".

- ^ Forster 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Frederick C. Beiser, The German Historicist Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 98.

- ^ Christopher John Murray (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Romantic Era, 1760–1850, Routledge, 2013, p. 491: "Herder expressed a view fundamental to Romantic hermeneutics..."; Forster 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Forster 2010, p. 42.

- ^ This thesis is prominent in This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774) and Ideas on the Philosophy of the History of Mankind (1784–91).

- ^ Forster 2010, p. 36.

- ^ Forster 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Barnard, F. M. (2005). In Herder on nationality, humanity and history (pp. 38–39). essay, McGill-Queen's University Press.

- ^ Forster 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Forster 2010, pp. 16 and 50 n. 6: "This thesis is already prominent in On Diligence in Several Learned Languages (1764)".

- ^ "Duden | Johann | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition". Duden (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2018.

Johann

- ^ "Duden | Gottfried | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition". Duden (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2018.

Gọttfried

- ^ "Duden | Herder | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition". Duden (in German). Retrieved 20 October 2018.

Hẹrder

- ^ Jacob, Margaret C. The Secular Enlightenment. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2019, 192

- ^ Columbia studies in the social sciences, Issue 341, 1966, p. 74.

- ^ Copleston, Frederick Charles. The Enlightenment: Voltaire to Kant. 2003. p. 146.

- ^ Jacob, Margaret C. ‘’The Secular Enlightenment’’. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2019, 193

- ^ Forster 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Jürgen Georg Backhaus (ed.), The University According to Humboldt: History, Policy, and Future Possibilities, Springer, 2015, p. 58.

- ^ Michael Forster (2007). "Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Johann Gottfried von Herder". Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ McNab, John (1972). Towards a Theology of Social Concern: A Comparative Study of the Elements for Social Concern in the Writings of Frederick D. Maurice and Walter Rauschenbusch (PhD thesis). Montreal: McGill University. p. 201. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ^ a b c Willson, A. Leslie. "Rogerius' "Open Deure": A Herder Source." Monatshefte 48, no. 1 (1956): 17–24. Accessed 3 October 2020. JSTOR 30166121.

- ^ Willson, A. Leslie. "Herder and India: The Genesis of a Mythical Image." PMLA 70, no. 5 (1955): 1049–058. Accessed 3 October 2020. doi:10.2307/459885.

- ^ Peleg, Yaron. Orientalism and the Hebrew Imagination. United States: Cornell University Press. p. 6.

- ^ Lifschitz, Avi (2012). Language & Enlightenment: The Berlin Debates of the Eighteenth Century. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 185–86. ISBN 978-0-19966166-4.

- ^ Votruba, Martin. "Herder on Language" (PDF). Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ^ "Hungarian history". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Barnard, F. M., "The Hebrews and Herder's Political Creed," Modern Language Review," vol. 54, no. 4, October 1959, pp. 533–546.

- ^ Copleston, Frederick Charles. The Enlightenment: Voltaire to Kant, 2003, p. 145.

- ^ Herder: Philosophical Writings, ed. M. N. Forster. Cambridge: 2002, p. 167

- ^ Headstrom, Birger R. (1929). Herder and the Theory of Evolution Archived 20 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Open Court 10 (2): 596–601.

- ^ a b Nisbet, H. B. (1970). Herder and the Philosophy and History of Science. Modern Humanities Research Association. pp. 210–212. ISBN 978-0900547065

- ^ a b Zimmerli, W. Ch. Evolution or Development? Questions Concerning the Systematic and Historical Position of Herder. In Kurt Mueller-Vollmer. (1990). Herder Today: Contributions from the International Herder Conference: 5–8 November 1987 Stanford, California. pp. 1–16. ISBN 0-89925-495-0

- ^ Osborn, Henry Fairfield. (1908). From the Greeks to Darwin: An Outline of the Development of the Evolution Idea. New York: Macmillan. p. 103

- ^ Köpke, Wulf (1987). Johann Gottfried Herder. Twayne Publishers, p. 58. ISBN 978-0-80576634-9

- ^ Mueller-Vollmer, Kurt (1990). Herder Today: Contributions from the International Herder Conference, Nov. 5–8, 1987, Stanford, California. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110117394 – via Google Books.

- ^ Menze, Ernest A.; Menges, Karl (2010). Johann Gottfried Herder: Selected Early Works, 1764–1767: Addresses, Essays, and Drafts; Fragments on Recent German Literature. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0271044972 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Forster, Michael N.; Herder, Johann Gottfried (2002). Forster, Michael N (ed.). Herder: Philosophical Writings. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139164634. ISBN 9780521790888.

- ^ Herder, Johann Gottfried (1985). Über die neuere deutsche Literatur: Fragmente. Aufbau-Verlag. ISBN 9783351001308 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Treatise on the Origin of Language by Johann Gottfried Herder 1772". www.marxists.org.

- ^ "Universitätsbibliothek Bielefeld – digitale Medien". www.ub.uni-bielefeld.de.

- ^ "Adrastea". -: Adrastea, -: – -.

- ^ Clark, Robert Thomas (1955). Herder: His Life and Thought. University of California Press. p. 426 – via Internet Archive.

herder adrastea.

References

[edit]- Michael N. Forster, After Herder: Philosophy of Language in the German Tradition, Oxford University Press, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Adler, Hans. "Johann Gottfried Herder's Concept of Humanity," Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 23 (1994): 55–74

- Adler, Hans and Wolf Koepke eds., A Companion to the Works of Johann Gottfried Herder. Rochester: Camden House 2009.

- Azurmendi, J. 2008. Volksgeist. Herri gogoa, Donostia, Elkar, ISBN 978-84-9783-404-9.

- Barnard, Frederick Mechner (1965). Herder's Social and Political Thought. Oxford, Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827151-4.

- Berman, Antoine. L'épreuve de l'étranger. Culture et traduction dans l'Allemagne romantique: Herder, Goethe, Schlegel, Novalis, Humboldt, Schleiermacher, Hölderlin., Paris, Gallimard, Essais, 1984. ISBN 978-2-07-070076-9

- Berlin, Isaiah, Vico and Herder. Two Studies in the History of Ideas, London, 1976.

- Berlin, Isaiah Three Critics of the Enlightenment: Vico, Hamann, Herder, London and Princeton, 2000, ISBN 0-691-05726-5

- Herder today. Contributions from the International Herder Conference, 5–8 November 1987, Stanford, California. Edited by Mueller-Vollmer Kurt. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter 1990, including

- Baum, Manfred, "Herder's Essay on Being," pp. 126–137.

- Simon Josef, "Herder and the Problematization of Metaphysics," pp. 108–125.

- DeSouza, Nigel and Anik Waldow eds., Herder. Philosophy and Anthropology. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2017.

- Iggers, Georg, The German Conception of History: The National Tradition of Historical Thought from Herder to the Present (2nd ed.; Wesleyan University Press, 1983).

- Noyes, John K., Herder. Aesthetics against Imperialism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press 2015.

- Noyes, John K. ed., Herder's Essay on Being. A Translation and Critical Approaches. Rochester: Camden House 2018.

- Sikka, Sonia, Herder on Humanity and Cultural Difference. Enlightened Relativism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2011.

- Taylor, Charles, The importance of Herder. In Isaiah Berlin: A celebration edited by Margalit Edna and Margalit Avishai. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1991. pp. 40–63; reprinted in: C. Taylor, Philosophical Arguments, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1995, pp. 79–99.

- Zammito, John H. Kant, Herder, the Birth of Anthropology. Chicago: Chicago University Press 2002.

- Zammito, John H., Karl Menges and Ernest A. Menze. "Johann Gottfried Herder Revisited: The Revolution in Scholarship in the Last Quarter Century," Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 71, Number 4, October 2010, pp. 661–684, in Project MUSE

External links

[edit]- Works by or about Johann Gottfried Herder at the Internet Archive

- Works by Johann Gottfried Herder at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Johann Gottfried von Herder". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Herder bibliography and more

- "Essay on the Origin of Language Archived 18 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine," 1772. Online in English translation.

- International Herder Society

- Selected works from Project Gutenberg (in German)

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Herder, Johann Gottfried von". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Herder". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Herder, Johann Gottfried von". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Herder, Johann Gottfried von". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Herder, Johann Gottfried von". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- The Jürgen Trabant Wilhelm von Humboldt Lectures

- Johann Gottfried Herder

- 1744 births

- 1803 deaths

- People from Morąg

- People from East Prussia

- Bavarian nobility

- German Lutheran theologians

- 18th-century German philosophers

- 18th-century German Protestant theologians

- 18th-century German writers

- 18th-century German male writers

- 18th-century German Lutheran clergy

- 19th-century German philosophers

- 19th-century German Protestant theologians

- 19th-century German writers

- 19th-century German male writers

- 19th-century German Lutheran clergy

- Age of Enlightenment

- German idealists

- Enlightenment philosophers

- German ethicists

- German-language poets

- German male non-fiction writers

- German nationalists

- German translation scholars

- Lutheran philosophers

- German philosophers of art

- German philosophers of culture

- German philosophers of education

- German philosophers of history

- German philosophers of language

- Philosophers of literature

- German philosophers of mind

- German philosophers of science

- German political philosophers

- Proto-evolutionary biologists

- Sturm und Drang

- German Freemasons

- Theoretical historians

- University of Königsberg alumni

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences