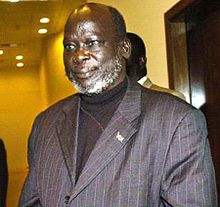

John Garang

Dr. John Garang | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Southern Sudan (Autonomous Region) | |

| In office July 9, 2005 – July 30, 2005 | |

| Vice President | Salva Kiir Mayardit |

| Preceded by | Position Created |

| Succeeded by | Salva Kiir Mayardit |

| First Vice President of Sudan | |

| In office January 9, 2005 – July 30, 2005 | |

| President | Omar al-Bashir |

| Preceded by | Ali Osman Taha |

| Succeeded by | Salva Kiir Mayardit |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Garang de Mabior June 23, 1945 Wangulei, Twic East, Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (present-day South Sudan) |

| Died | July 30, 2005 (aged 60) New Cush, Republic of Sudan (present-day South Sudan) |

| Nationality | South Sudanese |

| Political party | Sudan People's Liberation Movement |

| Spouse | Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior |

| Children | Mabior Garang De-Mabior Akuol de Mabior |

| Alma mater | Grinnell College (B.A.) Iowa State University (PhD) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1969–1972) (1972–1983) (1983–2005) |

| Years of service | 1969–2005 |

| Battles/wars | First Sudanese Civil War Second Sudanese Civil War |

Dr. John Garang De Mabior (June 23, 1945 – July 30, 2005)[1] was a Sudanese politician and revolutionary leader. From 1983 to 2005, he led the Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M, Now known as South Sudan People's Defense Forces) as a commander in chief during the Second Sudanese Civil War. He served as First Vice President of Sudan for three weeks, from the comprehensive peace agreement of 2005 until his death in a helicopter crash on July 30, 2005.[2] A developmental economist by profession,[3] Garang was one of the major influences on the movement that led to the foundation of South Sudan’s independence from the rule of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir.

Early life and education

[edit]Garang was a member of the Dinka ethnic group.[4] He was born into a poor family in Wangulei village Twic East County in the Upper Nile region of Sudan. An orphan by the age of ten, he had his fees for school paid by a relative, going to schools in Wau and then Rumbek. In 1962 he joined the First Sudanese Civil War, but because he was so young, the leaders encouraged him and others of his age to pursue education. Because of the ongoing fighting, Garang was forced to complete his secondary education in Tanzania. After winning a scholarship, he went on to earn a Bachelor of Arts in Economics in 1969 from Grinnell College in Iowa, United States.[5][6]

He was offered another scholarship to pursue graduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley, but chose to return to Tanzania and study East African agricultural economics as a Thomas J. Watson Fellow at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM). At UDSM, he was a member of the University Students' African Revolutionary Front. However, Garang soon returned to Sudan and joined the rebels.[7] There is much erroneous reporting that Garang met and befriended Yoweri Museveni, future president of Uganda, at this time; while both Garang and Museveni were students at UDSM in the 1960s, they did not attend at the same time.[8] In 1970, Garang was in one of the batches of Gordon Muortat Mayen's soldiers, the then leader of the Anyanya liberation movement, sent to Israel for military training.

The civil war ended with the Addis Ababa Agreement of 1972 and Garang, like many rebels, was absorbed into the Sudanese military. For eleven years, he was a career soldier and rose from the rank of captain to colonel after taking the Infantry Officers Advanced Course at Fort Benning, Georgia, United States. During this period he took four years academic leave and received a Master's degree in agricultural economics from Iowa State University (ISU).[9] In 1981, he earned a PhD in Economics from Iowa State University (ISU).[6][10][11] By 1983, Garang was serving as a senior instructor in the military academy in Wadi Sayedna 21 km from the centre of Omdurman where he instructed the cadets for more than four years. Later he was nominated to serve in the military research department at Army HQ in Khartoum.

Political ideology

[edit]Garang coined the philosophy of "Sudanism"[12] which would be the guiding philosophy to a secular and multiethnic New Sudan.[13] He believed, for the people of Sudan to live in cohesion, they must not separate themselves into the many existing ethnic factions present within the nation but, rather, to collectively renounce the belief that Black African-ness, Islam, or Christianity were to be the ultimate defining characteristics of Sudan. Rather, he willed that citizens should embrace all cultures of Sudan, including the creation of further pagan involvement into Sudanese life, a policy embraced by many of Sudan's elite, and to unify under the one commonality they all share, being Sudanese and coming from a background of Judaism, Christianity and Paganism.

Rebel leader

[edit]

In 1983, Garang went to Bor and southern government soldiers in Battalion 105 who were resisting being rotated to posts in the north. However, he was not among the officers in the Southern command arranging for the defection of Battalion 105 to the anti government rebels, but he was supporting the revolution. When the 105 Battalion attacked Sudanese army in Bor on 16 May 1983 under the command of Major Kerubino Kuanyin Bol, who was the leader of the budding movement which launched an impromptu attack, Garang rode by an alternative route to join them in the rebel stronghold in Ethiopia. Major Kerubino Kuanyin Bol and William Nyuon Bany Machar led Battalion 105 and 107 in Bor and Ayot, respectively. As a Major, Kerubino coalesced with William to organize a revolt and opened routes to Ethiopian plains. By the end of July, Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA) had brought over 3000 soldiers into the newly created Sudan People's Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M), which was opposed to military rule and Islamic dominance of the country, and encouraged other army garrisons to mutiny against the Islamic law imposed on the country by the government.[14] William Nyuon Bany and Kerubino Kwanyin Bol were both founding members of SPLA.[15] Bany was appointed the 3rd high-ranking Commander after Bol.[16]

This action marked the commonly agreed upon beginning of the Second Sudanese Civil War, which resulted in one and a half million deaths over twenty years of conflict. Although Garang was Christian and most of southern Sudan is non-Muslim (mostly animist), he did not initially focus on the religious aspects of the war.

Garang was a strong advocate for national unity: minorities together formed a majority and, therefore should rule. Together, Garang believed, they could replace President Omar al-Bashir with a government made up of representatives from “all tribes and religions in Sudan." His first real effort for the cause, under his command, occurred in July 1985 with the SPLA’s incursion into Kordofan.[17]

The SPLA gained the backing of Libya, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Garang and his army controlled a large part of the southern regions of the country, named "New Sudan". He claimed his troops' courage came from "the conviction that we are fighting a just cause. That is something North Sudan and its people don't have." Critics suggested financial motivations to his rebellion, noting that much of Sudan's oil wealth lies in the south of the country.[17]

In early 1991, Mengistu Haile Mariam's regime (in Ethiopia) was overthrown by the Khartoum-backed Ethiopian rebels (Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front). Upon the rebels’ seizure of the government, they closed all SPLA training camps in Ethiopia and cut off the SPLA's arms supply, forcing the SPLA to return hundreds of thousands of Sudanese back to South Sudan. This disrupted military operations and leadership within the SPLA. However, this caused the West to reconsider relations with the SPLA – justifying their providing the SPLA with "non-lethal help."[18]

Shortly after, there were leadership misunderstandings between Garang and senior SPLA commanders, Riek Machar and Lam Akol in August 1991. The splinter group led by Machar and Akol was named the SPLA-Nasir.[19] This resulted in Dinka Massacre [20] which raged civilians and exposed the deep ethnic divides within the SPLA. The Southern Sudanese communities became more divided than ever before in their history. These organic divides among the Southern Sudanese communities were exacerbated by the deliberate "divide and rule" policies instituted by the regimes in Khartoum, in order to maintain their power over the Southern Sudanese peoples.[citation needed] SPLA-Nasir accused Garang of ruling by force, in a "dictatorial reign of terror"; but ethnic rivalry seemed to have a part, with the Nasir faction mainly composed of Nuer, and Garang's supporters mainly Dinka people. Months of fighting between the two factions left thousands dead in early 1992.[21] The SPLA-Nasir also raised the idea of an independent south (whereas Garang wanted unity).[19]

On September 14, 1992, Bany, who was at the time Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the SPLA and Deputy Chairman of the SPLM, announced his defection from the SPLA, and escaped Garang territory. The following day, Commander Salva Kiir Mayardit was promoted from Chief of Staff to Bany's old positions of Deputy Commander-in-Chief and Deputy Chairman. Bany joined forces with Machar and Akol,[22] and later joined forces with Bol to form SPLA-United, Sudanese People's Liberation Army-United.[19]

Garang had refused to participate in the 1985 interim government or the 1986 elections, remaining a rebel leader. However, the SPLA and government signed a peace agreement on January 9, 2005, in Nairobi, in Kenya. On July 9, 2005, he was sworn in as the First-Vice-President – the second most powerful person in the country – following a ceremony in which he and President Omar al-Bashir signed a power-sharing constitution. Simultaneously, he became the premier in southern Sudan. This administration had limited autonomy for six years, at the end of which there would be a scheduled referendum regarding secession. No Christian or southerner had ever held such a high government post. Commenting after this ceremony, Garang stated, "I congratulate the Sudanese people, this is not my peace or the peace of al-Bashir, it is the peace of the Sudanese people."

In the Hillcrest Hotel in Nairobi on New Year's Day 2003, there was a meeting between the SPLA and the Fur people. Garang asked two associates of Abdul Wahid al Nur (who later formed the Sudan Liberation Movement) to declare that the Fur people were with the SPLA – they refused.[18]

Over 15 months, starting in September 2003, Ali Osman and Garang met in private in Naivasha. Their secret meetings and negotiations lasted up until the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) was initialed on New Year's Eve 2004.[18]

The CPA appeared to embody the vision of the "New Sudan" that Garang wanted. Within the CPA, power was split between the National Congress Party and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement for six years, until 2010, with Garang as the first vice-president.[18]

As a leader, John Garang's democratic credentials were often questioned. For example, according to Gill Lusk, "John Garang did not tolerate dissent and anyone who disagreed with him was either imprisoned or killed".[5] Under his leadership, the SPLA was accused of human rights abuses.[5]

The ideological profile of SPLA was as shadowy as Garang himself. He varied from Marxism to drawing support from Christian fundamentalists in the US.[5]

The United States State Department argued that Garang's presence in the government would have helped solve the Darfur conflict in western Sudan, but others consider these claims "excessively optimistic".[23] U.S. President George W. Bush, who supported South Sudanese independence, especially considered Garang to be a promising leader and called him a "partner in peace."[24] Bush highlighted Garang's Christian faith, and even connected him to support at evangelical churches in his hometown of Midland, Texas.[25]

Garang effectively used radio to advance his cause.[26]

Death

[edit]In late July 2005, Garang died after the Ugandan presidential Mi-172 helicopter he was flying in crashed. He had been returning from a meeting in Rwakitura with long-time ally President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda. He did not tell the Sudanese government that he was going to this meeting and therefore, did not take the presidential plane. In fact, Garang had said he was going to spend the weekend in New Cush, a small village near the Kenyan borders founded by Garang himself. To this day, neither the identity of any other participants at the meeting nor its purpose is known.

After the helicopter had been missing for more than 24 hours, the Ugandan president notified the Sudanese government, which in turn contacted the SPLM for information. The SPLM responded that the helicopter Garang was taking had landed safely at an old SPLA training camp. The Sudanese state television duly reported this. A few hours later, Abdel Basset Sabdarat, Sudan's Information Minister, then appeared on TV to refute the earlier report that Garang's helicopter landed safely. It was Yasir Arman, the SPLA/M spokesperson, who had told the government that Garang's plane had landed safely and his intention, in doing so, was to buy time for internal succession arrangements within the SPLA, before Garang's death was to be declared. Garang's helicopter crashed on Friday and he remained 'missing' throughout Saturday. During this time, the government believed he was still resolving his affairs in Southern Sudan. Finally, a statement released by the office of the Sudanese President, Omar el-Bashir, confirmed that the Ugandan presidential helicopter had crashed into "a mountain range in southern Sudan because of poor visibility and this resulted in the death of Dr. John Garang DeMabior, six of his colleagues and seven Ugandan crew members."[27] According to the Sudan Tribune John Garang's legacy was a major cornerstone in South Sudan's fight for independence. Without Garang, many marginalized people of Africa, including that of Sudan would still be largely forgotten about in the modern world.

His body was flown to New Cush, a southern Sudanese settlement near the scene of the crash, where former rebel fighters and civilian supporters gathered to pay their respects to Garang. Garang's funeral took place on August 3 in Juba.[28] His widow, Rebecca Nyandeng De Mabior, promised to continue his work stating: In our culture we say "if you kill the lion, you see what the lioness will do".[29]

Rumors

[edit]Both the Sudanese government and the head of the SPLA blamed the weather for the accident. There are, however, doubts as to whether this was the true cause, especially among the rank and file of the SPLA. Yoweri Museveni, the Ugandan President, stated that the possibility of "external factors" having played a role could not be eliminated.[citation needed]

The SPLM/SPLA Rumbek crisis, which took place in Rumbek from November 29 to December 1, 2004; one month before the signing of the CPA is also believed to have been a factor relevant to John Garang's death.[citation needed]

While the Sudanese people followed the Naivasha peace talks closely, with high hopes of freedom and democratic transformation, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) was rife with rumors and accusations of conspiracy relating to the removal of SPLM deputy Chairman, Salva Kiir Mayardit, and his replacement with the young Nhial Deng Nhial. Nhial Deng Nhial was the son of the famous leader of the southern Sudanese, William Deng Nhial, who had been assassinated by the Sudanese army in 1968. William Deng Nhial had led the Sudan African National Union (SANU) in exile, but had returned to Sudan to take part in the 1968 elections, shortly before he was killed. It has been reported that Salva Kiir disagreed with the amnesty afforded to Riek Machar and Lam Akol after their coup attempt against Garang in 2003; he also disliked Garang's decision to give Machar a leadership position as his deputy. It is rumored that in response to these actions by Garang, Kiir threatened to lead an armed revolt against South Sudan's leadership.[30]

See also

[edit]- Assassination of Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira

- First Sudanese Civil War

- List of unsolved deaths

- Second Sudanese Civil War

- Sudan People's Liberation Army

References

[edit]- ^ "Sudan VP Garang killed in crash". August 1, 2005. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Sudanese new government leaders take office". People's Daily Online. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ Wheeler, Jake (July 31, 2021). "Ten years after independence, South Sudan must return to Garang's vision". Revista de Prensa (in Spanish). Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ^ Moorcraft, Paul (April 30, 2015). Omar Al-Bashir and Africa's Longest War. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473828230.

- ^ a b c d Phombeah, Gray (August 3, 2005). "Obituary: John Garang". BBC News. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ a b "Leaders call death of former rebel leader a great loss to Sudan". The New York Times. August 2, 2005. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "Garang: Rebel leader to vice-president". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- ^ Prunier, Gérard (2009). Africa's World War: Congo, the Rwandan Genocide, and the Making of a Continental Catastrophe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537420-9., p. 80.

- ^ "Negotiating Peace in Sudan - John Garang de Mabior". Iowa State Lectures Program. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2023.

- ^ "A Voice for South Sudan". Iowa State University Alumni Association. Iowa State University (ISU). Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ Miller, Tim (July 31, 2007). "Sudanese students commemorate Garand death in US Iowa". Sudan Tribune News. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ A Speech by John Garang - FULL (YouTube)

- ^ "What is the government in view of Dr. John Garang". YouTube. Sudanese Online. March 27, 2012. Archived from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, D. The Root Causes of Sudan's Civil Wars, Indiana University Press, 2003, pp. 61–2.

- ^ Buay, Gordon (January 24, 2011). "Who Is CDR. William Nyuon Bany Machar?". Gurtong Trust. Archived from the original on June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ Teresa (June 21, 2019). "Brief Biography and Facts About Major(Cdr). Late William Nyuon Bany Machar". City Scrollz. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ a b Cockett, R., 2010, Sudan: Darfur and the Failure of an African State, Yale UP.

- ^ a b c d Flint, J. and Alex de Waal, 2008 (2nd Edn), Darfur: A New History of a Long War, Zed Books.

- ^ a b c "Pro-Government Militias:Documentation for Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army - United (SPLM/A-United)". Pro-Government Militias Database (PGMD). Extract from Christian Science Monitor, 14 April 1993. April 14, 1993. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Captain J. Liddell's Journeys in the White Nile Region". The Geographical Journal. 24 (6): 651–655. 1904. Bibcode:1904GeogJ..24..651.. doi:10.2307/1776256. JSTOR 1776256.

- ^ Banks, A.S.; Day, A.J.; Muller, T.C. (2016). Political Handbook of the World 1998. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 875. ISBN 978-1-349-14951-3. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ "The National Courier: TODAY IN HISTORY: William Nyuon Bany, on 27th of Sept 1992, Defects from SPLA/M In Pageri". Facebook. September 27, 2014. Archived from the original on February 26, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Reeves, Eric (August 2, 2005). "Untimely Death". The New Republic.

- ^ "Number of Sudan peacekeepers might need to be doubled, Bush says". February 17, 2006. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ McDonnell, Nick. "The Activist Alex de Waal among the war criminals". Harpers. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ Vicario, Danielle Del (2022). "John Garang On Air: Radio Battles in Sudan's Second Civil War". The Journal of African History. 63 (3): 309–327. doi:10.1017/S0021853722000597. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 253406737.

- ^ Mohamed Osman (August 1, 2005). "Sudanese vice president, 13 others, killed in air crash". South Tribune. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ "Sudan bids rebel leader farewell". BBC News. August 6, 2005.

- ^ Wax, Emily (August 30, 2005). "Widow of Sudan's Garang Steps In to Continue His Mission". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- ^ Jesus Deng Chaui (March 9, 2014). "Who Killed Hero Dr John Garang?". South Sudan News Agency. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Aufstand in der Dreistadt by Thomas Schimidinger in Jungle World Nr.32: August 10, 2005; ISSN 1613-0766

Publications

[edit]- Garang, John, 1987 John Garang Speaks. M. Khalid, ed. London: Kegan Paul International.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to John Garang at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Garang at Wikimedia Commons

- John Garang on National Public Radio

- Official website of the Sudan People's Liberation Army

- A State Department archive of information from before January 2001

- Sudan ex-rebel joins government, BBC, July 9, 2005

- Obituary, BBC

- Deadly riots erupt in Sudan after Garang death, Reuters, August 1, 2005

- The return of a Sudanese survivor, opinion piece in The Daily Star, Lebanon, July 19, 2005 – some info on early life

- Uganda Joins Sudan in Investigating Garang's Death, William Eagle, Voice of America, August 9, 2005

- John Garang’s mysterious death | Al Jazeera World Documentary, 26 Jul 2023.

- 1945 births

- 2005 deaths

- De Mabior family

- Dinka people

- Grinnell College alumni

- Iowa State University alumni

- People from Jonglei State

- Second Sudanese Civil War

- South Sudanese Protestants

- SPLM/SPLA Political-Military High Command

- State leaders killed in aviation accidents or incidents

- Sudanese expatriates in Tanzania

- Sudanese expatriates in the United States

- Sudan People's Liberation Movement politicians

- University of Dar es Salaam alumni

- Unsolved deaths

- Vice presidents of Sudan

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in Sudan

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 2005

- Victims of helicopter accidents or incidents

- Watson Fellows

- Former Marxists