Friday prayer

In Islam, Friday prayer, or Congregational prayer[1] (Arabic: صَلَاة ٱلْجُمُعَة, romanized: Ṣalāh al-Jumuʿa) is a community prayer service held once a week on Fridays.[2] All Muslim men are expected to participate at a mosque with certain exceptions due to distance and situation.[3] Women and children can also participate but do not fall under the same obligation that men do.[4] The service consists of several parts including ritual washing, chants, recitation of scripture and prayer, and sermons.[4]

Youm Jumu'ah ("day of congregation"), or simply Jumu'ah means Friday in Arabic. In many Muslim countries, the weekend is inclusive of Fridays, and in others, Fridays are half-days for schools and some workplaces. It is one of the most exalted Islamic rituals and one of its confirmed obligatory acts.

Service

[edit]The service consists of several parts including ritual washing, chants, recitation of scripture and prayer, and sermons.[5]

Ritual washing

[edit]

When entering the mosque, all worshippers practise wudu.[6][7]

Adhan and Iqama (call to prayer)

[edit]A Muezzin will recite a specific chant called an Adhan to call the congregation to the mosque, then to line up to begin the service.[5] The imam will then get up and recite The Sermon for Necessities. The first call summons Muslims to enter the mosque and then a second call, known as the iqama, summons those already in the mosque to line up for prayer.[5]

Khutbah sermon

[edit]

The imam will then get up and give a sermon called a Khutbah and recite prayer and verses from the Quran in Arabic.[5] The sermon is given in the local language and Arabic or completely in Arabic depending on the context.[8]

The imam performs the following:

- Stands and welcomes the congregation with a formal greeting in Arabic, then sits while the Adhan is recited.[9]

- Stands up and recites The Sermon for Necessities.[10]

- Recites verses from the Quran to invoke a sense of taqwa[8]

- Recites a supplication called a dua.

- Starts the khutbah and then at a certain point stops and asks Allah for forgiveness.[11]

- Sits down to leave space for the congregation to seek forgiveness from Allah.[12][13]

- Stands, praises Allah and Muhammed and then finishes the last part of the sermon.

- Recites additional dua and Salawat.

- Invites the congregation to line up for Jumu'ah prayer.[14]

According to the majority of Shiite and Sunni doctrine, the sermon must contain praise and glorification of Allah, invoke blessings on Muhammad and his progeny, and have a short quotation from the Quran in Arabic called a surah. It must also give the participants a sense of taqwa, admonition and exhortation.[8]

Jumu'ah prayer

[edit]

Juum'ah prayer consists of two rak'ats or prayer segments.[16] Shia and Sunni sects of Islam prescribe slight differences in this pattern but the following is a general outline of the steps of the prayer cycle.[17]

- A raka'ah begins when the worshipper begins by saying the Takbir or Glorification of God and pronounces the words "Allah is Greater", (Allah-Hu-Akbar).[5]

- In the second part of the raka'ah, the worshipper makes another Takbir and bows to a 90-degree angle, placing their hands on their knees with their feet kept shoulder-width apart, with their eyes focused in between their feet or around the area and bowing in humble submission as if awaiting God's command. During this position the words, "Glory be to Allah the most Magnificent" are uttered silently as a form of ritual praise.[18]

- The third movement of the raka'ah is to return from bowing to the standing position before, while saying the Takbir, then descending into full prostration on the ground.[19] In prostration, the worshipper's forehead and nose is flatly placed on the floor with the palm of their hands placed shoulder-width apart to the right and left of their ears.[19] During this position the words, "Glory be to Allah the Almighty" are repeated with contemplation as a form of ritual praise.

- The fourth movement is for the worshipper to return from prostration into a sitting position with their legs folded flatly under their body.[19]

According to Shi'ite doctrine, two qunut (raising one's hands for supplication during salat) is especially recommended during salatul Jum'ah. The first Qunut is offered in the 1st rak'at before ruku' and the second is offered in the 2nd rak'at after rising from ruku'.[20] According to Shiite doctrine, it is advisable (Sunnat) to recite Surah al-Jum'ah in the first rak'at and Surah al-Munafiqun in the second rak'at, after Surah al-Hamd.[20]

Religious significance

[edit]

Of the day Friday

[edit]Although Friday is not a sabbath in Islam it is recognized as a superior and holy day.[21] According to the Islamic scholar Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya there are 32 reasons that Friday is special.[21][22] Some of the reasons include a belief that Friday was the day when Adam was created, entered into, and expelled from Jannah.[23] It is also the day of the week when the Day of Judgment will occur and the world will end.[23] There is also a belief that Allah is more likely to forgive and bless on Fridays.[23] It is also believed to be the day that Islam was revealed to be perfected.[21]

Obligation

[edit]There is consensus among Muslims regarding the Friday prayer (salat al-jum'ah) being wajib – required – in accordance with the Quranic verse, as well as the many traditions narrated both by Shi'i and Sunni sources. According to the majority of Sunni schools and some Shiite jurists, Friday prayer is a religious obligation,[24] but their differences were based on whether its obligation is conditional to the presence of the ruler or his deputy in it or if it is wajib unconditionally. The Hanafis and the Twelver Imamis believe that the presence of the ruler or his deputy is necessary; the Friday prayer is not obligatory if neither of them is present. The Imamis require the ruler to be just ('adil); otherwise his presence is equal to his absence. To the Hanafis, his presence is sufficient even if he is not just. The Shafi'is, Malikis and Hanbalis attach no significance to the presence of the ruler.[25]

Moreover, it has been stated that Jum'ah is not obligatory for old men, children, women, slaves, travellers, the sick, blind and disabled, as well as those who are outside the limit of two farsakhs.[26][page needed]

In Islamic texts

[edit]Quran

[edit]It is mentioned in the Quran:

O you who have faith! When the call is made for prayer on Friday, hurry toward the remembrance of God, and leave all business. That is better for you, should you know. And when the prayer is finished, disperse through the land and seek God's grace, and remember God greatly so that you may be successful.

Hadith

[edit]Narrated Abu Huraira: Muhammad said, "On every Friday the angels take their stand at every gate of the mosques to write the names of the people chronologically (i.e. according to the time of their arrival for the Friday prayer) and when the Imam sits (on the pulpit) they fold up their scrolls and get ready to listen to the sermon."

Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj an-Naysaburi relates that Muhammad used to read Surah 87 (Al-Ala) and Surah 88, (Al-Ghashiya), in Eid Prayers and also in Friday prayers. If one of the festivals fell on a Friday, Muhammad would have made sure to read these two Surahs in the prayers.

Muhammad is quoted as saying "The best day the sun rises over is Friday; on it Allah created Adam. On it, he was made to enter paradise, on it he was expelled from it, and the Last Hour will take place on no other day than Friday." [Ahmad and at-Tirmithi].

Aws ibn Aws, narrated that Muhammad said: "Whoever performs Ghusl on Friday and causes (his wife) to do ghusl, then goes early to the mosque and attends from the beginning of the Khutbah and draws near to the Imam and listens to him attentively, Allah will give him the full reward of fasting all the days of a year and observing night-vigil on each of its nights for every step that he took towards the mosque." [Ibn Khuzaymah, Ahmad].

There are many hadiths reported on the significance of Jum'ah. The Muhammad has been reported saying:

- "The Jum'ah is the pilgrimage of the poor".[29]

- "Whoever misses three Jum'ah, being indifferent to them, Allah seals his heart".[30]

- "Any Muslim who dies during the day or night of Friday will be protected by Allah from the trial of the grave." [At-Tirmithi and Ahmad].

- Also, hadith related by Al-Bukhari, quoted the Prophet saying that: "In the day of Friday, there exists an hour that if a worshipper asks from Allah, anything he wishes in this hour, Allah will grant it and does not reject it, as long as he or she did not wish for bad".[31]

- "Friday has 12 hours, one of which is hour where dua are granted for Muslim believers. This hour is thought to be in the afternoon, after asr prayer".[32]

In Sunni Islam

[edit]

The Jum'ah prayer is half the Zuhr (dhuhr) prayer, for convenience, preceded by a khutbah (a sermon as a technical replacement of the two reduced rakaʿāt of the ordinary Zuhr (dhuhr) prayer), and followed by a congregational prayer, led by the imām. In most cases the khaṭīb also serves as the imam. Attendance is strictly incumbent upon all adult males who are legal residents of the locality.[33]

The muezzin (muʾadhdhin) makes the call to prayer, called the adhan, usually 15–20 minutes prior to the start of Jum'ah. When the khaṭīb takes his place on the minbar, a second adhan is made. The khaṭīb is supposed to deliver two sermons, stopping and sitting briefly between them. In practice, the first sermon is longer and contains most of the content. The second sermon is very brief and concludes with a dua, after which the muezzin calls the iqāmah. This signals the start of the main two rak'at prayer of Jum'ah.[citation needed]

In Shia Islam

[edit]

In Shia Islam, Salat al-Jum'ah is Wajib Takhyiri (at the time of Occultation),[34][35] which means that there is an option to offer Jum'ah prayers, if its necessary, conditions are fulfilled, or to offer Zuhr prayers. Hence, if Salat al-Jum'ah is offered then it is not necessary to offer Zuhr prayer. It is also recommended by Shiite Scholars to attend Jum'ah as it will become Wajib after the appearance of Imam al-Mahdi and Jesus Christ (Isa).[36]

Shiite (Imamite) attach high significance to the presence of a just ruler or his representative or Faqih and in the absence of a just ruler or his representative and a just faqih, there exists an option between performing either the Friday or the zuhr prayer, although preference lies with the performance of Friday prayer.[25][clarification needed]

History of the practice

[edit]According to the history of Islam and the report from Abdullah bn 'Abbas narrated from the Prophet saying that: the permission to perform the Friday prayer was given by Allah before hijrah, but the people were unable to congregate and perform it. The Prophet wrote a note to Mus'ab ibn Umayr, who represented the Prophet in Madinah to pray two raka'at in congregation on Friday (that is, Jumu'ah). Then, after the migration of the Prophet to Medina, the Jumu'ah was held by him.[37]

For Shiites, historically, their clergy discouraged Shiites from attending Friday prayers.[38][39] According to them, communal Friday prayers with a sermon were wrong and had lapsed (along with several other religious practices) until the return of their 12th Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi.[39] However, among others, Shiite modernist Muhammad ibn Muhammad Mahdi al-Khalisi (1890–1963) demanded that Shiites should more carefully observe Friday prayers in a step to bridge the gap with Sunnis.[40] Later, the practice of communal Friday prayers was developed, and became standard there-afterwards, by Ruhollah Khomeini in Iran and later by Mohammad Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr in Iraq. They justified the practice under the newly promoted Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists doctrine. When al-Sadr installed Friday prayer imams in Shia-majority areas—a practice not traditional in Iraqi Shiism and considered "revolutionary, if not heretical"[39]—it put him at odds with the Shia religious establishment in Najaf.[41] Under both Khomeini and al-Sadr, political sermons would be heard.[39]

Attendance rates

[edit]

The world's largest Muslim population can be found in Indonesia, where over 240 million Muslims live making up nearly 90% of Indonesia's total population. In the country, according to the World Values Survey conducted in the country in 2018,[42] 62.0% of Indonesians attend religious services at least once a week (including 54.0% of the population under the age of 30 and 66.1% of men). Most of these presumably would fall under the category of attending jumuah prayers. These numbers are stable from the same survey conducted in 2006,[42] where 64.5% of Indonesians attended religious services at least once a week (including 56.0% of the population under 30 and 64.3% of men).[citation needed]

The number of regular attendees is somewhat lower in the next largest Muslim-majority country, Pakistan, which has over 210 million Muslims making up over 95% of the population. The 2018 World Values Survey[42] conducted there found that 46.1% of Pakistanis attended religious services at least once a week (including 47.0% of Pakistanis under the age of 30 and 52.7% of men). However, this was a large increase from the same survey conducted in 2012,[42] where it was reported that only 28.9% of Pakistanis attended religious services at least once a week (including 21.5% of Pakistanis under the age of 30 and 31.4% of men). This is a testament to increasing religiosity in Pakistan, especially among the youth, who have gone from attending jumuah at rates far below that of the total population to attending at rates higher than the total population.[citation needed]

A different pattern is seen in the Muslim-majority country of Bangladesh (which has over 150 million Muslims making up over 90% of the population). There the 2002 World Values Survey[42] found that 56.1% of Bangladeshis attended religious services at least once a week (including 50.6% of Bangladeshis below the age of 30 and 61.7% of men), whereas sixteen years later in 2018,[42] the survey found that the number had dropped to 44.4% (including 41.3% of those under 30 and 48.8% of men).

Meanwhile, in the Arab country of Egypt, jumuah attendance has risen massively in recent years. The 2012 World Values Survey[42] found that 45.2% of Egyptians attended at least once a week (including 44.9% of Egyptians under the age of 30 and 60.1% of Egyptian men), but six years later the 2018 World Values Survey[42] found that the number of Egyptians attended at least once a week had risen to 57.0% (including 52.9% of those under 30 and 89.4% of men).

However, different patterns are found in the non-Arab Middle Eastern countries of Iran and Turkey. In these two countries, jumuah attendance is among the lowest in the world. The 2005 World Values Survey[42] in Iran found 33.8% of the population attending (including 27.3% of Iranians under 30 and 38.9% of Iranian men). By 2020, all these numbers had fallen, as only 26.1% of the population attended at least once a week (including 19.1% of Iranians under 30 and 29.3% of men). In Turkey, the 2012 World Values Survey[42] found 33.2% of the population attending (including 28.6% of Turks under 30 and 54.0% of men). Similarly, According to a 2012 survey by Pew Research Center, 19% of Turkish Muslims say that they attend Friday prayer once a week and 23% say they never visit their local mosque.[43] However, six years later in 2018, the World Values Survey reported that 33.8% of Turks attended (including 29.0% of those under 30 and 56.4% of men). This shows that even though both countries have relatively low religious attendance, religiosity is stronger in Turkey than in Iran, especially among the youth.

In several countries, such as in Central Asia and Balkans, self-reported Muslims practice the religion at low levels. According to a 2012 survey by Pew Research Center, about 1% of the Muslims in Azerbaijan, 5% in Albania, 9% in Uzbekistan, 10% in Kazakhstan, 19% in Russia and 22% in Kosovo said that they attend mosque once a week or more.[43] This was largely due to the religious restriction of Islam under communist rule, and attendance levels have been rising rapidly since the fall of the Soviet Union.

Mosque attendance rates in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have seen precipitous increases over the last decade. According to the World Values Survey, weekly attendance in Kazakhstan went from 9.0% in 2011 (including 8.7% among those under 30 and 9.6% among men) to 15.3% in 2018 (including 14.6% of those under 30 and 17.1% among men), while weekly attendance in Tajikistan climbed from 29.3% in 2011 (including 35.1% of those under 30 and 58.1% of men) to 33.2% in 2020 (including 35.1% of those under 30 and 58.1% of men). Generational replacement is in effect here as a more religious youthful contingent replaced a less religious contingent that grew up under the Soviet Union.

In the Middle East and North Africa, mosque attendance at least once a week ranges from 35% in Lebanon to 65% in Jordan.[43] Sub-Saharan African Muslim communities tend to have a high rates of mosque attendance, and ranges from 65% in Senegal to nearly 100% in Ghana.[43] In South Asia, home to the largest Muslim communities in the world,[44] mosque attendance at least once a week ranges from 53% in Bangladesh to 61% in Afghanistan.[43]

Surveys conducted in 1994 and in 1996 observed a decrease in religiosity among Muslims in Belgium based on lowering mosque participation, less frequent prayer, dropping importance attached to a religious education, etc.[45]: 242 This decrease in religiosity was more visible in younger Muslims.[45]: 243 A study published in 2006, found that 35% of the Muslim youth in Germany attend religious services regularly.[46] In 2009, 24% of Muslims in the Netherlands said they attended mosque once a week according to a survey.[47] According to a survey published in 2010, 20% of the French Muslims claimed to go regularly to the mosque for the Friday service.[48] Data from 2017 shows that American Muslim women and American Muslim men attend the mosque at similar rates (45% for men and 35% for women).[49]

Conditions

[edit]A valid Jum'ah is said to fulfill certain conditions:

- Friday prayer must be prayed in congregation.

- There are at least two persons present. This is based on the Hadith of Tariq Ibn Shihab who reported that Muhammad said, "Al-Jumuah is an obligation (wajib) upon every Muslim in the community." (An-Nasai). Scholars differ on how many people are required for performing Jumuah Prayer. The view believed to be the most correct is that Jumuah Prayer is valid if there are at least two people present. This is based on the hadith in which the Prophet is reported to have said, "Two or more constitute a congregation." (Ibn Majah). Imam Ash-Shawkani states, "The other prayers are considered to be made in congregation if there are two people present. The same applies to Friday prayer, unless there is a reason for it to be different. There is no evidence to show that [for the purpose of the congregation] its number should be larger than that for the other prayers."

- According to a Shiite law, only one Friday prayer may be prayed in a radius of 5.5 km. If two prayers are held within this distance, the latter is made null and void.

- There must be two sermons delivered by the imam before the prayer and attentively listened to by at least four (or six) persons.[20]

Format

[edit]Khutbah Jum'ah

[edit]- A talk or sermon delivered in mosques before the Friday prayer.[50] The sermon consists of two distinct parts, between which the Khatib (speaker) must sit down for a short time of rest.[51]

- There should not be an undue interval or irrelevant action intervening between the sermon and the prayer. "[52] It should preferably be in Arabic, especially the Qur'anic passage which has to be recited in the sermon. Otherwise, it should be given in the language understood by the majority of the faithful who are there. In this case, the preacher should first recite in Arabic Qurʾānic verses praising God and Muhammad. "[53]

- According to the majority of Shiite and Sunni doctrine, the contents must contain the following: "[54]

- The praise and glorification of Allah

- Invocation of blessings on Muhammad and his progeny

- Enjoining the participants piety, admonition and exhortations

- A short surah from the Quran

- In addition to the above issues, the following are advised to be addressed in the second sermon:

- Content that will be useful for all Muslims in this world and in the world thereafter

- Important events all over the world in favor of or in disfavor of Muslims

- Issues in the Muslim world

- Political and economical aspects of society and worldwide [55][56]

- Attendants must listen attentively to the sermon and avoid any action that might distract their attentions.[55]

- The Prophet Muhammad "has forbidden a person with his knees drawn up touching his abdomen while the imam is delivering the Friday sermon."[57]

Jumu'ah prayer

[edit]- Juum'ah prayer consists of two rak'ats prayers, as with morning prayer (fajr), offered immediately after Khutbah (the sermon). It is a replacement of Zuhr prayer.[36]

Qunut

[edit]- According to Shi'ite doctrine, two qunut (raising one's hands for supplication during salat) is especially recommended during salatul Jum'ah. The first Qunut is offered in the 1st rak'at before ruku' and the second is offered in the 2nd rak'at after rising from ruku'.[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Congregational Prayer". Learn Islam. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Fahd Salem Bahammam. The Muslim's Prayer. Modern Guide. ISBN 978-1909322950. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Al-Tusi, M. H. "A concise description of Islamic law and legal opinions." 2008

- ^ a b "Islam – Prayer, Salat, Rituals". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ a b c d e "Islam – Prayer, Salat". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Corpus Coranicum". corpuscoranicum.de.

- ^ "Sunan Ibn Majah 666 – The Book of Purification and its Sunnah – كتاب الطهارة وسننها Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com.

- ^ a b c "Sabiq As-Sayyid" "FIQH us – Sunnah". Indianapolis: American Trust Publishers, 1992.

- ^ "Giving salaams to people in the mosque during the khutbah – Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Khutbah al-Haajah – Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Is it prescribed for the khateeb to say "Aqoolu qawli haadha wa astaghfir-Allaah (I say these words of mine and I ask Allah for forgiveness)? – Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "What should be said when the imam sits down between the two khutbahs at Jumu'ah prayer? – Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ ʻAlī Nadvī, Abulḥasan (2006). The Musalman. the University of Michigan.

- ^ "Ruling on the imam saying to the congregation, "Pray Pray like a man bidding farewell" – Islam Question & Answer". islamqa.info. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

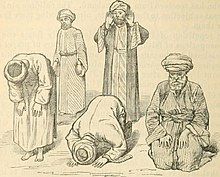

- ^ Image taken from page 168 of "Egypt : handbook for travellers: part first, lower Egypt, with the Fayum and the peninsula of Sinai" (1885)

- ^ "Sayyid Ali Al Husaini Seestani." Islamic Laws English Version of Taudhihul Masae' l. Createspace Independent, 2014 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Akhtar Rizvi, Sayyid Saeed (1989). Elements of Islamic Studies. Bilal Muslim Mission of Tanzania.

- ^ "Rakat – The nature of God – GCSE Religious Studies Revision – WJEC". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Rakat – The nature of God – GCSE Religious Studies Revision – WJEC". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Akhtar Rizvi, Sayyid Saeed (1989). Elements of Islamic Studies. Bilal Muslim Mission of Tanzania.

- ^ a b c "Why Is Friday So Special For Muslims?". About Islam. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah". sunnahonline.com. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "Blessings of Friday in Islam: Virtues, Prayer, and Acts". 19 March 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Hashemi, Kamran." Religious legal traditions, international human rights law and Muslim states. vol. 7. Brill, 2008

- ^ a b "Maghniyyah, M. J." The Five Schools of Islamic Law: Al-hanafi. Al-hanbali, Al-ja'fari, Al-maliki, Al-shafi'i. Anssariyan, 1995

- ^ Al-Tusi, M. H. "A concise description of Islamic law and legal opinions." 2008

- ^ Quran 62:9–10

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:13:51

- ^ "Shomali, Mohammad Ali and William Skudlarek, eds." Monks and Muslims: Monastic Spirituality in Dialogue with Islam. Liturgical Press, 2012.

- ^ Rayshahri, M. Muhammadi (2008). Scale of Wisdom: A Compendium of Shi'a Hadith: Bilingual Edition. ICAS Press.

- ^ "Sheikh Ramzy."The Complete Guide to Islamic Prayer (Salāh). 2012

- ^ "SW Al-Qahtani. "Fortress of the Muslim: Invocations from the Qur'an and Sunnah. Dakwah Corner Bookstore 2009

- ^ Margoliouth, G. (2003). "Sabbath (Muhammadan)". In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 893–894. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4.

- ^ Salah Jum'ah article.tebyan.net Retrieved 24 June 2018

- ^ Namaz (Prayer) Jum'a Archived 7 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine farsi.khamenei.ir Retrieved 24 June 2018

- ^ a b "Sayyid Ali Al Husaini Seestani." Islamic Laws English Version of Taudhihul Masae' l. Createspace Independent, 2014 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Rafat, Amari (2004). Islam: In Light of History. Religion Research Institute.

- ^ Gilles Kepel (2004). The War for Muslim Minds: Islam and the West (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0674015753.

- ^ a b c d Jonathan Steele (2008). Defeat: Why They Lost Iraq. I.B. Tauris. p. 96. ISBN 978-0857712004.

- ^ Brunner, Rainer; Ende, Werner, eds. (2001). The Twelver Shia in Modern Times: Religious Culture and Political History (illustrated ed.). Brill. p. 178. ISBN 978-9004118034.

- ^ Joel Rayburn (2014). Iraq after America: Strongmen, Sectarians, Resistance. Hoover Institution Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0817916947.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "World Values Survey". World Values Survey. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". Pew Research Center. 9 August 2012.

- ^ Pechilis, Karen; Raj, Selva J. (2013). South Asian Religions: Tradition and Today. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-44851-2.

- ^ a b Cesari, Jocelyne (2014). The Oxford Handbook of European Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199607976. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Frank Gesemann. "Die Integration junger Muslime in Deutschland. Interkultureller Dialog – Islam und Gesellschaft Nr. 5 (year of 2006). Friedrich Ebert Stiftung", on p. 9 – in German

- ^ CBS (29 July 2009). "Religie aan het begin van de 21ste eeuw". www.cbs.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ L'Islam en France et les réactions aux attentats du 11 septembre 2010, Résultats détaillés, Ifop, HV/LDV No. 1-33-1, 28 September 2010

- ^ "American Muslim Poll 2017 | ISPU". Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "Khutbah – Wiktionary". Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ ʻAlī Nadvī, Abulḥasan (2006). The Musalman. the University of Michigan.

- ^ "Muhammad Abdul-Rauf." Islam Creed and Worship. Islamic Center, 2008

- ^ "Chanfi Ahmed" West African ʿulamāʾ and Salafism in Mecca and Medina. Journal of Religion in Africa 47.2, 2018. Reference. 2018

- ^ "Sabiq As-Sayyid" "FIQH us-SUNNAH". Indianapolis: American Trust Publishers, 1992.

- ^ a b "Ayatullah Shahid Murtadha Mutahhari"Salatul Jum'ah in the Thoughts and Words of Ayatullah Shahid Murtadha Mutahhari . Al-Fath Al-Mubin Publications.

- ^ "Ilyas Ba-Yunus, Kassim Kone" Muslims in the United States. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006.

- ^ Davids, Abu Muneer (2006). The ultimate guide to Umrah (1st ed.). Darussalam. ISBN 978-9960969046.

External links

[edit]