Neltuma juliflora

| Neltuma juliflora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Young tree | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Subfamily: | Caesalpinioideae |

| Clade: | Mimosoid clade |

| Genus: | Neltuma |

| Species: | N. juliflora

|

| Binomial name | |

| Neltuma juliflora (Sw.) Raf.

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Many, see text | |

Neltuma juliflora (Spanish: bayahonda blanca, Cuji in Venezuela, Trupillo in Colombia, Aippia in the Wayuunaiki language and long-thorn kiawe[1] in Hawaii), formerly Prosopis juliflora, is a shrub or small tree in the family Fabaceae, a kind of mesquite.[2] It is native to Mexico, South America and the Caribbean. It has become established as an invasive weed in Africa, Asia, Australia and elsewhere.[3] It is a contributing factor to continuing transmission of malaria, especially during dry periods when sugar sources from native plants are largely unavailable to mosquitoes.[4]

Description

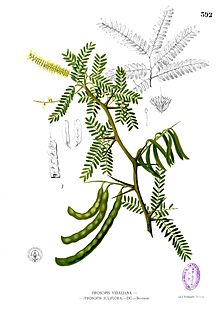

[edit]Growing to a height of up to 12 metres (39 feet), N. juliflora has a trunk diameter of up to 1.2 m (4 ft).[5] Its leaves are deciduous, geminate-pinnate, light green, with 12 to 20 leaflets. Flowers appear shortly after leaf development. The flowers are in 5–10 centimetres (2–4 inches) long green-yellow cylindrical spikes, which occur in clusters of 2 to 5 at the ends of branches. Pods are 20 to 30 cm (8 to 12 in) long and contain between 10 and 30 seeds per pod. A mature plant can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds. Seeds remain viable for up to 10 years. The tree reproduces solely by way of seeds, not vegetatively. Seeds are spread by cattle and other animals, which consume the seed pods and spread the seeds in their droppings.[6]

Its roots are able to grow to a great depth in search of water similar to Prosopis species. The tree is said to have been introduced to Sri Lanka in the 19th century, where it is now known as vanni-andara, or katu andara in Sinhala. It is claimed that N. juliflora existed and was recognised even as a holy tree in ancient India, but this is most likely a confusion with P. cineraria. The tree is believed to have existed in the Vanni and Mannar regions for a long time.[citation needed] This species has thorns in pairs at the nodes. The species has variable thorniness, with nearly thornless individuals appearing occasionally.

In the western extent of its range in Ecuador and Peru, N. juliflora readily hybridises with Prosopis pallida and can be difficult to distinguish from this similar species or their interspecific hybrid strains.[7]

Nomenclature

[edit]

Vernacular names

[edit]Neltuma juliflora has a wide range of vernacular names, although no widely used English one except for mesquite, which is also used for several species of Prosopis. It is called bayahonda blanca in Spanish, bayarone Français in French, and bayawonn in Creole. Other similar names are also used, including bayahonde, bayahonda and bayarone, but these may also refer to any Neotropical member of the genus Prosopis. In Tamil this bush tree is called சீமைக் கருவேலம் (seemai karuvelam). The tree is known by a range of other names in various parts of the world, including algarrobe, cambrón, cashaw, épinard, mesquite, mostrenco, or mathenge.[8] Many of the less-specific names are because over large parts of its range, it is the most familiar and common species of mesquite, and thus to locals simply "the" bayahonde, algarrobe, etc. "Velvet mesquite" is sometimes given as an English name, but properly refers to a different species, Prosopis velutina.[5]

In the late 1800s in the states of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas it was known by the common names of mesquit and algaroba. In Texas and New Mexico it was also known as honey locust, a name it shared even at the time with the much more widely known Gleditsia triacanthos in Texas. In Texas it was additionally called honey pod and ironwood.[9]

Synonyms

[edit]This plant has been described under a number of now-invalid scientific names:[3]

- Acacia cumanensis Willd.

- Acacia juliflora (Sw.) Willd.

- Acacia salinarum (Vahl) DC.

- Algarobia juliflora (Sw.) Heynh.

- Algarobia juliflora as defined by G. Bentham refers only to the typical variety, Prosopis juliflora var. juliflora (Sw.) DC

- Desmanthus salinarum (Vahl) Steud.

- Mimosa juliflora Sw.

- Mimosa piliflora Sw.

- Mimosa salinarum Vahl

- Neltuma bakeri Britton & Rose

- Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC.

- Neltuma occidenatlis Britton & Rose

- Neltuma occidentalis Britton & Rose

- Neltuma pallescens Britton & Rose

- Prosopis bracteolata DC.

- Prosopis cumanensis (Willd.) Kunth

- Prosopis domingensis DC.

- Prosopis dulcis Kunth var. domingensis (DC.)Benth.

- C.S. Kunth's Prosopis dulcis is Smooth Mesquite (P. laevigata), while P. dulcis as described by W.J. Hooker is Caldén (P. caldenia).

- Prosopis vidaliana Fern.-Vill.[10]

Prosopis chilensis was sometimes considered to belong here too, but is now usually considered a separate species.[5] Several other authors misapplied P. chilensis to P. glandulosa (honey mesquite).[3]

Etymology

[edit]Names in and around Indian Subcontinent, where the species is widely used for firewood and to make barriers, often compare it to similar trees and note its introduced status; thus in Hindi it is called angaraji babul, Kabuli kikar, vilayati babul, vilayati khejra or vilayati kikar. The angaraji and vilayati names mean they were introduced by Europeans, while Kabuli kikar (or keekar) means "Kabul acacia"; babul specifically refers to Acacia nilotica and khejra (or khejri) to Proposis. cineraria, both of which are native to South Asia.In Maharashtra it is known as "Katkali (काटकळी)". In Gujarati it is called gando baval (ગાંડો બાવળ- literally translating to "the mad tree")[11] and in Marwari, baavlia. In Kannada it is known as Ballaari Jaali ( ಬಳ್ಳಾರಿ ಜಾಲಿ) meaning "Jaali", local name, abundant in and around Bellary district. In Tamil Nadu, in Tamil language it is known as seemai karuvel (சீமைக்கருவேலை), which can be analysed as சீமை ("foreign (or non-native)") + கருவேலை (Vachellia nilotica). Another Tamil name is velikathan (வேலிகாத்தான்), from veli (வேலி) "fence" and kathan (காத்தான்) "protector", for its use to make spiny barriers. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, in the Telugu language it is known as mulla tumma (ముల్ల తుమ్మ),sarkar tumma,"chilla chettu","Japan Tumma Chettu", "Seema Jaali", or "Kampa Chettu". In Malayalam, it is known as "Mullan". A vernacular. The Somali name is 'Garan-waa' which means 'the unknown'. In the Wayuu language, spoken on the La Guajira Peninsula in northern Colombia and Venezuela, it is called trupillo or turpío.[12] In Kenya it is called Mathenge.

As an invasive species

[edit]N. juliflora has become an invasive weed in several countries where it was introduced. It is considered a noxious invader in Ethiopia, Hawaii,[1] Sri Lanka, Jamaica, Kenya, the Middle East, India, Nigeria, Sudan, Somalia, Senegal, South Africa, Namibia and Botswana. It is also a major weed in the southwestern United States. It is hard and expensive to remove as the plant can regenerate from the roots.[13]

In Australia, mesquite has colonized more than 800,000 hectares (2,000,000 acres) of arable land, having severe economic and environmental impacts. With its thorns and many low branches it forms impenetrable thickets which prevent cattle from accessing watering holes, etc. It also takes over pastoral grasslands and uses scarce water. Livestock which consume excessive amounts of seed pods are poisoned due to neurotoxic alkaloids. It causes land erosion due to the loss of the grasslands that are habitats for native plants and animals. It also provides shelter for feral animals such as pigs and cats.[13]

In the Afar Region in Ethiopia, where the mesquite was introduced in the late 1970s and early 1980s, its aggressive growth leads to a monoculture, denying native plants water and sunlight, and not providing food for native animals and cattle. The regional government with the non-governmental organisation FARM-Africa are looking for ways to commercialize the tree's wood, but pastoralists who call it the "Devil Tree" insist that N. juliflora be eradicated.[14]

In Sri Lanka this mesquite was planted in the 1950s near Hambantota as a shade and erosion control tree. It then invaded the grasslands in and around Hambantota and the Bundala National Park, causing similar problems as in Australia and Ethiopia.[6] N. juliflora native to Central and South America is also known as katu andara. It was introduced in 1880 and has become a serious problem as an invasive species.[15]

In the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, N. juliflora has emerged as an invasive species. The plant was first introduced by the British in 1877 as part of an effort to plant it along the arid tracts of Southern India. During the 1960s the state government of Tamil Nadu under Chief Minister K. Kamaraj,[16] encouraged the planting of Neltuma juliflora to overcome the shortage of firewood faced by the state at the time, it was also grown as a fence to protect agricultural fields from animals.[17] In 2017, the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court ordered the state government to eradicate the species from the state. In 2022, unsatisfied with the state government, the Madras High Court directed the government to immediately frame a policy to eradicate the plant.[18] The state on 13 July 2022 unveiled a policy to eliminate the invasive species.[19]

In Europe, N. juliflora is included since 2019 in the list of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern (the Union list).[20] This implies that this species cannot be imported, cultivated, transported, commercialized, planted, or intentionally released into the environment in the whole of the European Union.[21]

Potential toxicity

[edit]The seed pods contain neurotoxic alkaloids which are toxic when eaten excessively by livestock.[13]

Uses

[edit]The sweet pods are edible and nutritious, and have been a traditional source of food for indigenous peoples in Peru, Chile and California.[22] Pods were once chewed during long journeys to stave off thirst.[22] They can be eaten raw, boiled, dried and ground into flour to make bread,[22] stored underground, or fermented to make a mildly alcoholic beverage.[23]

The species' uses also include forage, wood and environmental management. The plant possesses an unusual amount of the flavanol (-)-mesquitol in its heartwood.[24]

In the Macará Canton of Ecuador, N. juliflora can be found in dry forests where it is one of the species most frequently harvested for multiple forest products.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Long-thorn Kiawe". Hawaii Invasive Species Council. 2013-02-21. Retrieved 2020-11-08.

- ^ "Neltuma juliflora (Sw.) Raf". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ a b c "Prosopis juliflora - ILDIS LegumeWeb". www.ildis.org. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ Muller, Gunter C.; Junnila, Amy; Traore, Mohamad M.; Traore, Sekou F.; Doumbia, Seydou; Sissoko, Fatoumata; Dembele, Seydou M.; Schlein, Yosef; Arheart, Kristopher L. (2017-07-05). "The invasive shrub Prosopis juliflora enhances the malaria parasite transmission capacity of Anopheles mosquitoes: a habitat manipulation experiment". Malaria Journal. 16 (1): 237. doi:10.1186/s12936-017-1878-9. PMC 5497341. PMID 28676093.

- ^ a b c "Prosopis juliflora". www.hort.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ a b Lalith Gunasekera, Invasive Plants: A guide to the identification of the most invasive plants of Sri Lanka, Colombo 2009, pp. 101-102.

- ^ Pasiecznik, Harris, and Smith (2004). Identifying Tropical Prosopis Species (PDF). Coventry, UK: Henry Doubleday Research Association.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Factsheet: Prosopis juliflora (prosopis or mesquite)".

- ^ Sudworth, George Bishop (1897). Nomenclature of the Arborescent Flora of the United States. Washington, D.C.: Department of Agriculture, Forestry Division. pp. 251–253. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ "Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC". The Plant List - A working list of all plant species. 2013.

- ^ "An army of mad trees". www.downtoearth.org.in. 15 April 1999. Retrieved 2021-02-04.

- ^ Villalobos et al. (2007)

- ^ a b c "Mesquite (Prosopis species)"Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Canberra Archived 2017-03-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Caroline Irby, "Devil of a problem: the tree that's eating Africa" Archived 2008-08-20 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 14 January 2009)

- ^ Gunasekera, Lalith (6 December 2011). "Will Katu-andara Destroy the Biodiversity of Bundala Wet Land?". The Sri Lanka Guardian. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ^ "Seemai karuvelam, a saviour-turned-villain whose tentacles spread far and wide". The Hindu. 2017-02-27. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2023-08-21.

- ^ Kolappan, B. (2017-02-28). "Seemai karuvelam, a saviour-turned-villain whose tentacles spread far and wide". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ James, Sebin (2022-02-02). "Full Bench Of Madras High Court Directs State To Immediately Frame Action Plan For Removal Of Invasive 'Seemai Karuvelam' Trees". www.livelaw.in. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ "State Unveils Policy To Rid Tamil Nadu Of 'seemai Karuvelam' | Chennai News - Times of India". The Times of India. TNN. Jul 15, 2022. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ "List of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern - Environment - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- ^ "REGULATION (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European parliament and of the council of 22 October 2014 on the prevention and management of the introduction and spread of invasive alien species".

- ^ a b c Pieroni, Andrea (2005). Prance, Ghillean; Nesbitt, Mark (eds.). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 0415927463.

- ^ Peattie, Donald Culross (1953). A Natural History of Western Trees. New York: Bonanza Books. pp. 559, 562.

- ^ Unusual amount of (-)-mesquitol from the heartwood of Prosopis juliflora. Sirmah Peter, Dumarcay Stephane, Masson Eric and Gerardin Philippe, Natural Product Research, Volume 23, Number 2, January 2009 , pp. 183-189

- ^ Mendoza, Zhofre Aguirre (8 September 2014). "Productos forestales no maderables de los bosques secos de Macara, Loja, Ecuador". Retrieved 2018-11-10.

Further reading

[edit]- Duke, James A. (1983): Prosopis juliflora DC.. In: Handbook of Energy Crops. Purdue University Center for New Crops & Plant Products. Version of 1998-JAN-08. Retrieved 2008-MAR-19.

- International Legume Database & Information Service (ILDIS) (2005): Prosopis juliflora. Version 10.01, November 2005. Retrieved 2007-DEC-20.

- Villalobos, Soraya; Vargas, Orlando & Melo, Sandra (2007): Uso, manejo y conservacion de "yosú", Stenocereus griseus (Cactaceae) en la Alta Guajira colombiana [Usage, Management and Conservation of yosú, Stenocereus griseus (Cactaceae), in the Upper Guajira, Colombia]. [Spanish with English abstract] Acta Biológica Colombiana 12(1): 99-112. PDF fulltext

External links

[edit] Media related to Prosopis juliflora at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Prosopis juliflora at Wikimedia Commons- Prosopis juliflora in West African plants – A Photo Guide.

- Long-thorn Kiawe | Hawaii Invasive Species Council

- Prosopis juliflora (mesquite) - CABI Invasive Species Compendium

- Long-thorn Kiawe | Kauai Invasive Species Committee (KISC)

- Prosopis juliflora (Fabaceae) | Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk

- Prosopis juliflora | Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk | Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk

- Prosopis juliflora | GISD