Qinghai

Qinghai

青海 | |

|---|---|

| Province of Qinghai | |

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 青海省 (Qīnghǎi Shěng) |

| • Abbreviation | QH / 青 (pinyin: Qīng) |

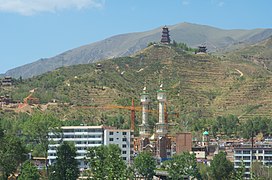

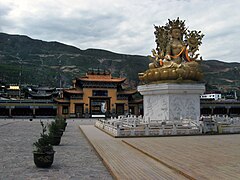

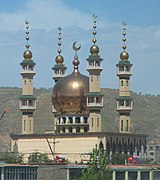

Clockwise from the top:

| |

Map showing the location of Qinghai Province | |

| Coordinates: 35°N 96°E / 35°N 96°E | |

| Country | China |

| Named for | Derived from the name of Qinghai Lake ("blue/green lake"). |

| Capital (and largest city) | Xining |

| Divisions - Prefecture-level - County-level - Township- level | 8 prefectures 44 counties 404 towns and subdistricts |

| Government | |

| • Body | Qinghai Provincial People's Congress |

| • Party Secretary | Wu Xiaojun |

| • Congress Chairman | Chen Gang (titular) |

| • Governor | Luo Dongchuan (acting) |

| • Provincial CPPCC Chairman | Gönbo Zhaxi |

| • National People's Congress Representation | 24 deputies |

| Area | |

• Total | 720,000 km2 (280,000 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 4th |

| Highest elevation | 6,860 m (22,510 ft) |

| Population (2020)[2] | |

• Total | 5,923,957 |

| • Rank | 31st |

| • Density | 8.2/km2 (21/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 30th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition | Han – 54% Tibetan – 21% Hui – 16% Tu – 4% Mongol – 1.8% Salar – 1.8% |

| • Languages and dialects | Zhongyuan Mandarin Chinese, Amdo Tibetan, Monguor, Oirat Mongolian, Salar and Western Yugur |

| GDP (2023)[3] | |

| • Total | CN¥ 379,906 million (30th)

US$ 53,913 million |

| • Per capita | CN¥ 63,903 (24th)

US$ 9,069 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-QH |

| HDI (2022) | 0.719[4] (30th) – high |

| Website | www |

| Qinghai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Qinghai" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 青海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Tsinghai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Qinghai (Lake)" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | མཚོ་སྔོན། | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | Хөхнуур | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mongolian script | ᠬᠥᠬᠡ ᠨᠠᠭᠤᠷ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchu script | ᡥᡠᡥᡠ ᠨᠣᠣᡵ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romanization | Huhu Noor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oirat name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oirat | Kokonur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Qinghai[a] is an inland province in Northwestern China. It is the largest province of China (excluding autonomous regions) by area and has the third smallest population. Its capital and largest city is Xining.

Qinghai borders Gansu on the northeast, Xinjiang on the northwest, Sichuan on the southeast and the Tibet Autonomous Region on the southwest. Qinghai province was established in 1928 during the period of the Republic of China, and until 1949 was ruled by Chinese Muslim warlords known as the Ma clique. The Chinese name "Qinghai" is after Qinghai Lake, the largest lake in China. The lake is known as Tso ngon in Tibetan, and as Kokonor Lake in English, derived from the Mongol Oirat name for Qinghai Lake. Both Tso ngon and Kokonor are names found in historic documents to describe the region.[7]

Located mostly on the Tibetan Plateau, the province is inhabited by a number of peoples including the Han (concentrated in the provincial capital of Xining, nearby Haidong, and Haixi), Tibetans, Hui, Mongols, Monguors, and Salars. According to the 2021 census reports, Tibetans constitute a fifth of the population of Qinghai and the Hui compose roughly a sixth of the population. There are over 37 recognized ethnic groups among Qinghai's population of 5.6 million, with national minorities making up a total of 49.5% of the population.

The area of Qinghai came under the control of the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty around 1724, after their defeat of Khoshut Mongols who previously controlled most of the area. After the Xinhai Revolution and the ensuing fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, Qinghai came under Chinese Muslim warlord Ma Qi's control until the Northern Expedition by the Republic of China consolidated central control in 1928. In the same year, the province of Qinghai was established by the Nationalist Government, with Xining as its capital.[8][9][10]

History

[edit]During the Bronze Age, Qinghai was home to a diverse group of nomadic tribes closely related to other Central Asians who traditionally made a living in agriculture and husbandry, the Kayue culture. The eastern part of the area of Qinghai was under the control of the Han dynasty about 2,000 years ago. It was a battleground during the Tang and subsequent Central Plain dynasties when they fought against successive Tibetan tribes.[11]

In the middle of 3rd century CE, nomadic people related to the Mongolic Xianbei migrated to pasture lands around the Qinghai Lake (Koko Nur) and established the Tuyuhun Kingdom.

In the 7th century, the Tuyuhun Kingdom was attacked by both the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty as both sought control over the Silk Road trade routes. Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo was victorious, and settled the area around Tso ngon (Lake Go, or Kokonor Lake).[12] Military conflicts had severely weakened the Tuyuhun kingdom and it was incorporated into the Tibetan Empire. The Tibetan Empire continued expanding beyond Tso ngon during Trisong Detsen's and Ralpacan's reigns, and the empire controlled vast areas north and east of Tso ngon until 848,[13] which included Xi'an.

During the fragmentation of the Tibetan Empire, a series of local polities emerged under the political jostling of Western Xia to the north and Song dynasty to the east -- from the military-rule of Guiyi Circuit, to a Tibetan tribal confederacy, and eventually the Tibetan theocratic kingdom of Tsongkha. The Song dynasty eventually defeated the Kokonor kingdom Tsongkha in the 1070s.[14] During the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty's administrative rule of Tibet, the region comprised the headwaters of the Ma chu (Machu River, Yellow River) and the Yalong (Yangtze) rivers and was known as Amdo, but apportioned to different administrative divisions than Tibet proper.[15]

Most of Qinghai was, for a short time in the aftermath of the Yuan dynasty's overthrow, under the control of early Ming dynasty, but later gradually lost to the Khoshut Khanate founded by the Oirats. The Xunhua Salar Autonomous County is where most Salar people live in Qinghai. The Salars migrated to Qinghai from Samarkand in 1370.[16] The chief of the four upper clans around this time was Han Pao-yuan and Ming granted him office of centurion, it was at this time the people of his four clans took Han as their surname.[17] The other chief Han Shan-pa of the four lower Salar clans got the same office from Ming, and his clans were the ones who took Ma as their surname.[18]

From 1640 to 1724, a big part of the area that is now Qinghai was under Khoshut Mongol control, but in 1724 it was conquered by the armies of the Qing dynasty.[19] Xining, the capital of modern Qinghai province, began to function as the administrative center, although the city itself was then part of Gansu province within the "Tibetan frontier district".[20][21] In 1724, 13-Article for the Effective Governing of Qinghai (Chinese:青海善后事宜十三条) was proposed by Nian Gengyao and adopted by the Central Government to gain full control of Qinghai.

Under the Qing dynasty, the governor was a viceroy of the Emperor, but local ethnic groups enjoyed significant autonomy. Many chiefs retained their traditional authority, participating in local administrations.[22] The Dungan Revolt (1862–1877) devastated the Hui Muslim population of Shaanxi, shifting the Hui center of population to Gansu and Qinghai.[23]: 405 Another Dungan Revolt broke out in Qinghai in 1895 when various Muslim ethnic groups in Qinghai and Gansu rebelled against the Qing. Following the overthrow of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the region came under Chinese Muslim warlord Ma Qi control until the Northern Expedition by the Republic of China consolidated central control in 1928.

In July–August 1912, General Ma Fuxiang was "Acting Chief Executive Officer of Kokonur" (de facto Governor of the region that later became Qinghai).[24] In 1928, Qinghai province was created. The Muslim warlord and General Ma Qi became military governor of Qinghai, followed by his brother Ma Lin and then Ma Qi's son Ma Bufang. In 1932 Tibet invaded Qinghai, attempting to capture southern parts of Qinghai province, following contention in Yushu, Qinghai, over a monastery in 1932. The army of Ma Bufang defeated the Tibetan armies. Governor of Qinghai Ma Bufang was described as a socialist by American journalist John Roderick and friendly compared to the other Ma Clique warlords.[25] Ma Bufang was reported to be good humoured and jovial in contrast to the brutal reign of Ma Hongkui.[26] Most of eastern China was ravaged by the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War, by contrast, Qinghai was relatively untouched.

Ma Bufang increased the prominence of the Hui and Salar people in Qinghai's politics by heavily recruiting to his army from the counties in which those ethnic groups predominated.[27] General Ma started a state run and controlled industrialization project, directly creating educational, medical, agricultural, and sanitation projects, run or assisted by the state. The state provided money for food and uniforms in all schools, state run or private. Roads and a theater were constructed. The state controlled all the press, no freedom was allowed for independent journalists.[28]

As the 1949 Chinese revolution approached Qinghai, Ma Bufang abandoned his post and flew to Hong Kong, traveling abroad but never returning to China. On January 1, 1950, the Qinghai Province People's Government was declared, owing its allegiance to the new People's Republic of China. Aside from some minor adjustments to suit the geography, the PRC maintained the province's territorial integrity.[29] Resistance to Communist rule continued in the form of the Huis' Kuomintang Islamic insurgency (1950–58), spreading past traditionally Hui areas to the ethnic-Tibetan south.[23]: 408 Although the Hui composed 15.6% of Qinghai's population in 1949, making the province the second-largest concentration of Hui after Ningxia, the state denied the Hui ethnic autonomous townships and counties that their numbers warranted under Chinese law until the 1980s.[23]: 411

-

The Khoshut Khanate (1642–1717) based in the Tibetan Plateau

-

Chiang Kai-shek, leader of Nationalist China (right), meets with the Muslim generals Ma Bufang (second from left), and Ma Buqing (first from left) in Xining, Qinghai, in August 1942

Geography

[edit]Qinghai is located on the northeastern part of the Tibetan Plateau. By area, it is the largest province in the People's Republic of China (excluding the autonomous regions).

The Yellow River originates in the southern part of the province, while the Yangtze and Mekong have their sources in the southwestern part. Qinghai is separated by the Riyue Mountain into pastoral and agricultural zones in the west and east.[30]

The Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve is located in Qinghai and contains the headwaters of the Yellow River, Yangtze River, and Mekong River. The reserve was established to protect the headwaters of these three rivers and consists of 18 subareas, each containing three zones which are managed with differing degrees of strictness.

Qinghai Lake is the largest salt water lake in China, and the second largest in the world. Other large lakes are Lake Hala in the Qilian mountains, lakes Gyaring and Ngoring in the headwater region of the Yellow River, Lake Donggi Cona, and many saline and salt lakes in the western part of the province.

The Qaidam basin lies in the northwest part of the province at an altitude between 3000 and 5000 meters above sea level. About a third of this resource rich basin is desert.

-

Nyenpo Yurtse, Jigzhi County, Qinghai

-

Riyue Mountain in Qinghai

Climate

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (December 2022) |

The average elevation of Qinghai is approximately 3000 m.[31] Mountain ranges include the Tanggula Mountains and Kunlun Mountains, with the highest point being Bukadaban Feng at 6860 m.[32] Due to the high altitude, Qinghai has quite cold winters (harsh in the highest elevations), mild summers, and a large diurnal temperature variation.[citation needed] Its mean annual temperature is approximately −5 to 8 °C (23 to 46 °F), with January temperatures ranging from −18 to −7 °C (0 to 19 °F) and July temperatures ranging from 15 to 21 °C (59 to 70 °F).[citation needed] It is also prone to heavy winds as well as sandstorms from February to April. Significant rainfall occurs mainly in summer, while precipitation is very low in winter and spring, and is generally low enough to keep much of the province semi-arid or arid.[citation needed]

Politics

[edit]The Politics of Qinghai Province in the People's Republic of China are structured in a one party-government system like all other governing institutions in mainland China.

The Governor of Qinghai (青海省省长) is the highest-ranking official in the People's Government of Qinghai. However, in the province's dual party-government governing system, the Governor has less power than the Qinghai Chinese Communist Party Committee Secretary (青海省委书记), colloquially termed the "Qinghai Party Chief".

Administrative divisions

[edit]Because the Han form Qinghai's ethnic majority[30] and because none of its many ethnic minorities have clear dominance over the rest, the province is not administered as an autonomous region. Instead, the province has many ethnic autonomous areas at the district and county levels.[27] Qinghai is administratively divided into eight prefecture-level divisions: two prefecture-level cities and six autonomous prefectures:

| Administrative divisions of Qinghai | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code[33] | Division | Area in km2[34] | Population 2010[35] | Seat | Divisions[36] | |||

| Districts | Counties | Aut. counties | CL cities | |||||

| 630000 | Qinghai Province | 720,000.00 | 5,626,723 | Xining city | 7 | 25 | 7 | 5 |

| 630100 | Xining city | 7,424.11 | 2,208,708 | Chengzhong District | 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| 630200 | Haidong city | 13,043.99 | 1,396,845 | Ledu District | 2 | 4 | ||

| 632200 | Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 33,349.99 | 273,304 | Haiyan County | 3 | 1 | ||

| 632300 | Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 17,908.89 | 256,716 | Tongren city | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 632500 | Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 43,377.11 | 441,691 | Gonghe County | 5 | |||

| 632600 | Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 76,442.38 | 181,682 | Maqên County | 6 | |||

| 632700 | Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 197,953.70 | 378,439 | Yushu city | 5 | 1 | ||

| 632800 | Haixi Mongol and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 300,854.48 | 489,338 | Delingha city | 3 | 3 | ||

| Administrative divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | ||

| Qinghai Province | 青海省 | Qīnghǎi Shěng | ||

| Xining city | 西宁市 | Xīníng Shì | ||

| Haidong city | 海东市 | Hǎidōng Shì | ||

| Haibei Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 海北藏族自治州 | Hǎiběi Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

| Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 黄南藏族自治州 | Huángnán Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

| Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 海南藏族自治州 | Hǎinán Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

| Golog Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 果洛藏族自治州 | Guǒluò Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

| Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 玉树藏族自治州 | Yùshù Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

| Haixi Mongol and Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 海西蒙古族藏族自治州 | Hǎixī Měnggǔzú Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

The eight prefecture-level divisions of Qinghai are subdivided into 44 county-level divisions (6 districts, 4 county-level cities, 27 counties and 7 autonomous counties).

Urban areas

[edit]| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Cities | 2020 Urban area[37] | 2010 Urban area[38] | 2020 City proper |

| 1 | Xining | 1,677,177 | 1,153,417 | 2,467,965 |

| 2 | Haidong | 204,784 | [b] | 1,358,471 |

| 3 | Golmud | 197,153 | 156,779 | part of Haixi Prefecture |

| 4 | Yushu | 85,497 | [c] | part of Yushu Prefecture |

| 5 | Delingha | 65,424 | 54,844 | part of Haixi Prefecture |

| (6) | Tongren | 49,962[d] | part of Huangnan Prefecture | |

| 7 | Mangnai | 18,856 | [e] | part of Haixi Prefecture |

- ^ /tʃɪŋˈhaɪ/ ching-HY;[5] Chinese: 青海, IPA: [tɕʰíŋ.xàɪ] ⓘ; alternately romanized as Tsinghai or Chinghai)[6]

- ^ Haidong Prefecture is currently known as Haidong PLC after 2010 census; Ledu County & Ping'an County is currently known as Ledu & Ping'an (core districts of Haidong) after 2010 census.

- ^ Yushu County is currently known as Yushu CLC after 2010 census.

- ^ Tongren County is currently known as Tongren CLC after 2020 census.

- ^ Mangnai Administrative Zone & Lenghu Administrative Zone County is currently known as Mangnai CLC after 2010 census.

Population

[edit]Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912[39] | 368,000 | — |

| 1928[40] | 619,000 | +68.2% |

| 1936–37[41] | 1,196,000 | +93.2% |

| 1947[42] | 1,308,000 | +9.4% |

| 1954[43] | 1,676,534 | +28.2% |

| 1964[44] | 2,145,604 | +28.0% |

| 1982[45] | 3,895,706 | +81.6% |

| 1990[46] | 4,456,946 | +14.4% |

| 2000[47] | 4,822,963 | +8.2% |

| 2010[48] | 5,626,722 | +16.7% |

| 2020 | 5,923,957 | +5.3% |

Ethnicity

[edit]There are over 37 recognized ethnic groups among Qinghai's population of 5.6 million, with Han population standing at 50.5% of the total population and national minorities making up 49.5% of the population.[49] In 2010, Tibetan population stood at 20.7%, Hui 16%, Tu (Monguor) 4%, with also some groups of Mongol, and Salar, all of those groups being the most populous in the province. Han Chinese predominate in the cities of Xining, Haidong, Delingha and Golmud, and elsewhere in the northeast. The Hui are concentrated in Xining, Haidong, Minhe County, Hualong County, and Datong County. The Tu people predominate in Huzhu County and the Salars in Xunhua County; Tibetans and Mongols are sparsely distributed across the rural western part of the province.[27] Of the Muslim ethnic groups in China, Qinghai has communities of Hui, Salar, Dongxiang, and Bao'an.[16] The Hui dominate the wholesale business in Qinghai.[50]

Religion

[edit]Religion in Qinghai (2000s)

The predominant religions in Qinghai are Chinese folk religions (including Taoist traditions and Confucianism) and Chinese Buddhism among the Han Chinese. The large Tibetan population practices Tibetan schools of Buddhism or traditional Tibetan Bön religion, while the Hui Chinese practice Islam. Christianity is the religion of 0.76% of the province's population according to the Chinese General Social Survey of 2004.[52] According to a survey of 2010, 17.51% of the population of Qinghai follow Islam.[51]

From September 1848, the city was the seat of a short-lived Latin Catholic Apostolic Vicariate (pre-diocesan missionary jurisdiction) of Kokonur (alias Khouhkou-noor, Kokonoor), but it was suppressed in 1861. No incumbent(s) recorded.[53]

|

Culture

[edit]Qinghai has been influenced by interactions "between Mongol and Tibetan culture, north to south, and Han Chinese and Inner Asia Muslim culture, east to west".[27] The languages of Qinghai have for centuries formed a Sprachbund, with Zhongyuan Mandarin, Amdo Tibetan, Salar, Yugur, and Monguor borrowing from and influencing one another.[54] In mainstream Chinese culture, Qinghai is most associated with the Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven.[citation needed] According to this legend, King Mu of Zhou (r. 976–922 BCE) pursued hostile Quanrong nomads to eastern Qinghai, where the goddess Xi Wangmu threw the king a banquet in the Kunlun Mountains.[55]

The main religions in Qinghai are Tibetan Buddhism, Islam and Chinese Folk Religions. The Dongguan Mosque has been continuously operating since 1380.[23]: 402 Measures of education in Qinghai are low, particularly among the ethnic minorities.[27] The yak, which is native to Qinghai, is widely used in the province for transportation and its meat.[30] The Mongols of Qinghai celebrate the Naadam festival on the Qaidam Basin every year.[56]

Economy

[edit]

Qinghai's economy is amongst the smallest in China. Its nominal GDP in 2022 was just RMB 361 billion (US$50 billion) and contributes to about 0.30% of the entire country's economy. Per capita GDP was RMB 60,724 (US$9,028) (nominal), the 24th in China.[57]

Its heavy industry includes iron and steel production, located near its capital city of Xining. Oil and natural gas from the Qaidam Basin have also been an important contributor to the economy.[58] Salt works operate at many of the province's numerous salt lakes.

Outside of the provincial capital, Xining, most of Qinghai remains underdeveloped. Qinghai ranks second lowest in China in terms of highway length, and will require a significant expansion of its infrastructure to capitalize on the economic potential of its rich natural resources.[58]

Economic and technological development zone

[edit]Xining Economic & Technological Development Zone (XETDZ) was approved as state-level development zone in July 2000. It has a planned area of 4.4 km2. XETDZ lies in the east of Xining, 5 km from the city centre. Xining is located in the east of the province at the upper reaches of the Huangshui River, one of the Yellow River's branches. The city is surrounded by mountains with an average elevation of 2261 m, the highest at 4393 m. XETDZ is the first of its kind at the national level on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. It is established to fulfill the nation's strategy of developing the west.

XETDZ enjoys a convenient transportation system, connected by the Xining-Lanzhou expressway and running through by two main roads, the broadest in the city. It is 4 km from the railway station, 15 km from Xi'ning Airport—a grade 4D airport with 14 airlines to cities such as Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, Chengdu and Xi'an. Xining is Qinghai province's passage to the outside world, a transportation hub with more than ten highways, over 100 roads and two railways, Lanzhou-Qinghai and Qinghai-Tibet Railways in and out of the city.

It focuses on the development of following industries: chemicals based on salt lake resources, nonferrous metals, and petroleum and natural gas processing; special medicine, foods and bio-chemicals using local plateau animals and plants; new products involving ecological and environmental protection, high technology, new materials as well as information technology; and services such as logistics, banking, real estate, tourism, hotel, catering, agency and international trade.[59]

Tourism

[edit]

Many tourist attractions center on Xining, the provincial seat of Qinghai.

During the hot summer months, many tourists from the hot southern and eastern parts of China travel to Xining, as the climate of Xining in July and August is quite mild and comfortable, making the city an ideal summer retreat.

Qinghai Lake (青海湖; qīnghǎi hú) is another tourist attraction, albeit further from Xining than Kumbum Monastery (Ta'er Si). The lake is the largest saltwater lake in China, and is also located on the "Roof of the World", the Tibetan Plateau. The lake itself lies at 3,600 m elevation. The surrounding area is made up of rolling grasslands and populated by ethnic Tibetans. Most pre-arranged tours stop at Bird Island (鸟岛; niǎo dǎo). An international bicycle race takes place annually from Xining to Qinghai Lake.

Transportation

[edit]

The Lanqing Railway, running between Lanzhou, Gansu and Xining, the province's capital, was completed in 1959 and is the major transportation route in and out of the province. A continuation of the line, the Qinghai-Tibet Railway via Golmud and western Qinghai, has become one of the most ambitious projects in PRC history. It was completed in October 2005 and now links Tibet with the rest of China through Qinghai.

Construction on the Golmud–Dunhuang Railway, in the province's northwestern part, started in 2012.

Six National Highways run through the province.

Xining Caojiabao International Airport provides service to Beijing, Lanzhou, Golmud and Delingha. Smaller regional airports, Delingha Airport, Golog Maqin Airport, Huatugou Airport, Qilian Airport and Yushu Batang Airport, serve the province's smaller communities; plans exist for the construction of three more by 2020.[60]

Telecommunications

[edit]Since the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology began its "Access to Telephones Project", Qinghai has invested 640 million yuan to provide telephone access to 3,860 out of its 4,133 administrative villages. At the end of 2006, 299 towns had received Internet access. However, 6.6 percent of villages in the region still have no access to the telephone. These villages are mainly scattered in Qingnan Area, with 90 percent of them located in Yushu and Guoluo. The average altitude of these areas exceeds 3600 meters, and the poor natural conditions hamper the establishment of telecommunications facilities in the region.

Satellite phones have been provided to 186 remote villages in Qinghai Province as of September 14, 2007.[citation needed] The areas benefited were Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture and Guoluo Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. Qinghai has recently been provided with satellite telephone access. In June 2007, China Satcom carried out an in-depth survey in Yushu and Guoluo, and made a special satellite phones for these areas. Two phones were provided to each village for free, and calls were charged at the rate of 0.2 RMB (about a quarter of a US cent at that time) per minute for both local and national calls, with the extra charges assumed by China Satcom. No monthly rent was charged on the satellite phone. International calls were also available.

Colleges and universities

[edit]- Qinghai University (青海大学)

- Qinghai Normal University (青海师范大学)

- Qinghai University for Nationalities (青海民族大学)

- Qinghai Medical College (青海医学院)

- Qinghai Radio & Television University (青海广播电视大学)

See also

[edit]- 2010 Yushu earthquake

- Amdo

- Geladandong

- Haplogroup D-M15 (Y-DNA)

- Haplogroup O3 (Y-DNA)

- Iris qinghainica (native plant of Qinghai)

- Major national historical and cultural sites in Qinghai

- Tectonic summary of Qinghai

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Qinghai Province". Qinghai Province Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ "Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 3)". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "National Data". China NBS. March 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024. see also "zh: 2023年青海省国民经济和社会发展统计公报". qinghai.gov.cn. February 29, 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024. The average exchange rate of 2023 was CNY 7.0467 to 1 USD dollar "Statistical communiqué of the People's Republic of China on the 2023 national economic and social development" (Press release). China NBS. February 29, 2024. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Indices (8.0)- China". Global Data Lab. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ "Qinghai". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021.

- ^ 中国地名录 (2nd ed.). Beijing: China Maps Press. 1995. p. 309. ISBN 7-5031-1718-4.

- ^ Gangchen Khishong, 2001. Tibet and Manchu: An Assessment of Tibet-Manchu Relations in Five Phases of Development. Dharmasala: Narthang Press, p.1-70.

- ^ "中華民國政府令". 國民政府公報. Vol. 93. Republic of China: 國民政府秘書處. Sep 1928. p. 5.

- ^ "中華民國十七年十月十九日 中華民國政府令". 國民政府公報. No. 2. Republic of China: 國民政府文官處印鑄局. 27 Oct 1928. p. 9.

- ^ "中華民國十八年一月二十九日 國民政府指令一八九號". 國民政府公報. No. 80. Republic of China: 國民政府文官處印鑄局. 31 Jan 1929. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Purdue – Tibetan history Archived 2007-08-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Laurent Deshayes, 1997. Histoire du Tibet. Paris: Fayard.

- ^ Gertraud Taenzer, 2012. The Dunhuang Region during Tibetan Rule (787-848). (Berlin): Harrassowitz Verlag.

- ^ Leung 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Smith, Warren W (2009). China's Tibet?: Autonomy or Assimilation. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 24, 252.

- ^ a b Betta, Chiara (2004). The Other Middle Kingdom: A Brief History of Muslims in China. Indianapolis University Press. p. 21.

- ^ William Ewart Gladstone, Baron Arthur Hamilton-Gordon Stanmore (1961). Gladstone-Gordon correspondence, 1851–1896: selections from the private correspondence of a British Prime Minister and a colonial Governor, Volume 51. American Philosophical Society. p. 27. ISBN 9780871695147. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ William Ewart Gladstone, Baron Arthur Hamilton-Gordon Stanmore (1961). Gladstone-Gordon correspondence, 1851–1896: selections from the private correspondence of a British Prime Minister and a colonial Governor, Volume 51. American Philosophical Society. p. 27. ISBN 9780871695147. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ The Times Atlas of World History. (Maplewood, New Jersey: Hammond, 1989) p. 175

- ^ Louis M. J. Schram (2006). The Monguors of the Kansu-Tibetan Frontier: Their Origin, History, and Social Organization. Kessinger Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 1-4286-5932-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Graham Hutchings (2003). Modern China: a guide to a century of change (illustrated, reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 351. ISBN 0-674-01240-2. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ M.C. Goldstein (1994). Barnett and Akiner (ed.). Change, Conflict and Continuity among a community of nomadic pastoralists—A Case Study from western Tibet, 1950–1990., Resistance and Reform in Tibet. London: Hurst & Co.

- ^ a b c d Cooke, Susette. "Surviving State and Society in Northwest China: The Hui Experience in Qinghai Province under the PRC." Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 28.3 (2008): 401–420.

- ^ Henry George Wandesforde Woodhead, Henry Thurburn Montague Bell (1969). The China year book, Part 2. North China Daily News & Herald. p. 841. Retrieved 2011-06-05.

- ^ John Roderick (1993). Covering China: the story of an American reporter from revolutionary days to the Deng era. Imprint Publications. p. 104. ISBN 1-879176-17-3. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Felix Smith (1995). China pilot: flying for Chiang and Chennault. Brassey's. p. 140. ISBN 1-57488-051-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman, David (2004). China's Campaign to "Open Up the West": National, Provincial, and Local Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–83.

- ^ Werner Draguhn; David S. G. Goodman (2002). China's communist revolutions: fifty years of the People's Republic of China. Psychology Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-7007-1630-0. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- ^ Blondeau, Anne-Marie; Buffetrille, Katia (2008). Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China's 100 Questions. University of California Press. pp. 203–205.

It is often assumed that this current policy [of not politically uniting all ethnically Tibetan areas] reflects the PRC leadership's intention to divide and rule Tibet, but this assumption is not wholly accurate.... The PRC cemented the [historical] status quo by keeping Amdo/Qinghai as a separate, multinational province... China does not reverse perceived territorial acquisitions. Hence, all territories that escaped the domination of Lhasa in recent history remained attached to the neighboring Chinese constituencies they tended to be under the influence of.

- ^ a b c Lahtinen, Anja (2009). "Maximising Opportunities for the Tibetans of Qinghai Province, China". In Cao, Huahua (ed.). Ethnic Minorities and Regional Development in Asia: Reality and Challenges. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 20–22.

- ^ "Qinghai Province Mountains".

- ^ Bukadaban Feng, Peakbagger.com

- ^ 中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码 (in Simplified Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs.

- ^ Shenzhen Statistical Bureau. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》 (in Simplified Chinese). China Statistics Print. Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- ^ Census Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China; Population and Employment Statistics Division of the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分乡、镇、街道资料 (1 ed.). Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.

- ^ Ministry of Civil Affairs (August 2014). 《中国民政统计年鉴2014》 (in Simplified Chinese). China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-7130-9.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2022). 中国2020年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-9772-9.

- ^ 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- ^ 1912年中国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 1928年中国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 1936–37年中国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 1947年全国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于第一次全国人口调查登记结果的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009.

- ^ 第二次全国人口普查结果的几项主要统计数字. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九八二年人口普查主要数字的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九九〇年人口普查主要数据的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on June 19, 2012.

- ^ 现将2000年第五次全国人口普查快速汇总的人口地区分布数据公布如下. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012.

- ^ "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013.

- ^ "How Much Does Beijing Control the Ethnic Makeup of Tibet?". ChinaFile. 2021-09-02. Retrieved 2023-05-08.

- ^ "Demand for an aphrodisiac has brought unprecedented wealth to rural Tibet—and trouble in its wake". The Economist. 19 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ a b Min Junqing. The Present Situation and Characteristics of Contemporary Islam in China. JISMOR, 8. 2010 Islam by province, page 29. Data from: Yang Zongde, Study on Current Muslim Population in China, Jinan Muslim, 2, 2010.

- ^ a b China General Social Survey (CGSS) 2009. Report by: Xiuhua Wang (2015, p. 15) Archived September 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Apostolic Vicariate of Kokonur, China". Archived from the original on 2018-03-22. Retrieved 2017-02-27.

- ^ Janhunen, Juha (2006). "From Manchuria to Amdo Qinghai: On the Ethnic Implications of the Tuyuhun Migration". Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 111–112.

- ^ Asiapac Editorial (2006). Chinese History: Ancient China to 1911. Asiapac Books. p. 28.

- ^ "Qaidam culture shines in Qinghai, NW China". Global Times. 2009-07-21. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-06-05.

- ^ "National Data". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Qinghai Province: Economic News and Statistics for Qinghai's Economy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-10-25.

- ^ RightSite.asia|Xining Economic & Technological Development Zone

- ^ "Qinghai to build 3 new airports before 2020". Archived from the original on 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

General sources

[edit]External links

[edit]- Official website (in Chinese)

- Memorials from Qinghai from the 19th century.