Jazz Hot

| |

| |

| Editor-in-chief | Yves Sportis |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Quarterly |

| Format | Print Digital Mobile device |

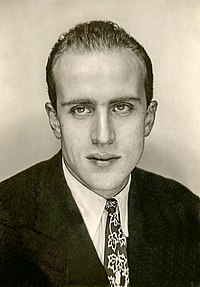

| Publisher | Jazz Hot Publications Charles Delaunay (1947–1980) |

| Founder | Hugues Panassié Charles Delaunay |

| Founded | March 1, 1935 – 1st series October 1, 1945 – 2nd series |

| First issue | March 1, 1935 |

| Company | Jazz Hot Publications |

| Country | France |

| Based in | Marseille |

| Language | French |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 0021-5643 |

Jazz Hot is a French quarterly jazz magazine published in Marseille. It was founded in March 1935 in Paris.

Early years

[edit]

Jazz Hot is acclaimed for having innovated scholarly jazz criticism before and after World War II — jazz criticism that was also distinguished with literary merit, and in some articles before 1968, with leftist political views. Several of its early contributors are credited for helping to intellectualize jazz journalism and to draw attention to it from fine arts establishments and institutions.[1][i] Jazz Hot has played an integral role integrating jazz into a French national identity.[2]

From inception of the First and Second Series, until November 2007, Jazz Hot was published monthly but irregularly, typically combining months in the summers and sometimes the winters. Beginning with Issue No. 649, Fall 2009, Jazz Hot, has been published quarterly, regularly. The pre-World War II series — March 1935, Issue No. 1 to July–August 1939, Issue No. 32 — is referred to as the "First Series" or the "Original Series" or the "Pre-War Series." The First Series was bilingual, in French and selectively in English. The postwar series, beginning with Issue No. 1 in October 1945, was referred to as the "Second Series" or the "New Series" or the "Post-World War II Series." The Second Series was and still is in French only.[3]

World's oldest jazz publication

[edit]Although the American jazz magazine DownBeat was founded four months before Jazz Hot, it was not exclusively a jazz magazine at the time. Therefore, Jazz Hot is the oldest jazz magazine in the world, but the distinction has two caveats. Oldest does not mean longest running; publication of Jazz Hot was interrupted during World War II, giving way to jazz magazines that have been published without interruption. The issue sequence of the pre-war series, from March 1935 to July–August 1939, numbers 1 through 32, is independent from the issue sequence of the post-war series, which begins October 1945 with issue 1, which clouds the connection between the two series.

Jazz Hot was published in March 1935 in Paris on one page in the back of a program for a Coleman Hawkins concert at the Salle Pleyel on February 21, 1935. At its inception, Jazz Hot was the official magazine of the Hot Club of France, an organization founded in January 1934 by Panassié as president and Pierre Nourry as secretary general.[2][4][ii] In August 1938, the club was dissolved and reestablished with Panassié as president and Charles Delaunay as secretary general.[5] The club was primarily interested in Dixieland recordings, revival of Dixieland — which had lost popularity due to the swing craze of the 1930s — record listening sessions, and camaraderie among like-mined enthusiasts. Panassié and Delaunay were the founders of the Jazz Hot.

Before World War II, Jazz Hot was instrumental in the club's efforts to curate, restore, and import live and recorded Dixieland. The magazine endured under the auspices of the Hot Club of France for 45 issues — the entire 32 issues before World War II and first 13 consecutive issues after World War II — until February 1947, when it became privately owned and headed by Delaunay.[6][7][8]

Jazz Hot suspended publication — the last being July–August 1939, Issue No. 32 — for 6 years, 1 month. Panassié spent the war years at his chateau in the unoccupied zone of Southern France and Delaunay, using the Hot Club as cover, gathered intelligence that was transmitted to England. He also traveled around France, organizing concerts, and giving lectures on music — all sanctioned by the Propaganda-Staffel. Unable to publish Jazz Hot, Delaunay issued clandestine, one-page publications. Following the Decree of July 17, 1941, Delaunay began issuing a clandestine, one-page duplex sheet, Circulaire du Hot Club de France from September 1941 to June 1945 that was inserted in the programs of Hot Club concerts.[9] The Hot Club of France resumed publishing Bulletin du Hot Club de France in December 1945 as Issue No. 1.

Dispute over the definition of jazz

[edit]Panassié, editor-in-chief since the founding of Jazz Hot before the war, was adamant his entire life that "authentic jazz" was strictly Dixieland of the 1920s and Chicago-style jazz — or hot jazz similar to the style of Louis Armstrong and others. Panassié further insisted that "real jazz" was the music of African Americans and that non-African Americans could only aspire to be imitators or exploiters of African Americans.[10][11]

In music, primitive man generally has greater talent than civilized man. An excess of culture atrophies inspiration.

For music is, above all, the cry of the heart, the natural, spontaneous song expressing what man feels within himself.

When Panassié heard a bebop recording of "Salt Peanuts" in 1945, he refused to accept it as jazz and frequently admonished its artists and proponents. He harbored the same objections to cool and other progressive jazz. His refusal to accept new genres of jazz as "real jazz" lasted his entire life.

Panassié argued that real jazz was innately inspired. He praised so-called black rhythm over white harmony and innate black jazz talent over white jazz mastery. As one musician put it, "If a black man knows some [stuff], that's talent. If a white guy knows the same [stuff], he's smart.[15] For Panassié, Gillespie's and Parker's foray into bebop, despite the fact that they were African Americans, represented a betrayal to African American jazz musicians and a departure from jazz itself because bebop required learned musicianship, which, according to Panassié, contaminated jazz because it was white music.

Panassié also argued that jazz was an art that should not be contaminated by commercialism. He was one of the most hostile critics of swing, which emerged in the 1930s.[16][17]

From June 22, 1940, to November 11, 1944, Germany occupied Northern France, Panassié spent that time safely at his family's château in Gironde[18] in the unoccupied zone of Southern France, isolated from developments in jazz. Bebop began to develop in Harlem late 1939. The outrage by Panassié began when Delaunay, in 1945, sent him a 1944 Musicraft bebop recording of Dizzy Gillespie's "Salt Peanuts", a 1943 composition by Gillespie and Kenny Clarke.[19][9][20]

Panassié's views ceased to reflect the views of Jazz Hot when he left the magazine in 1946. But because he was a co-founder of Jazz Hot and because he set a standard for covering jazz as editor-in-chief of Jazz Hot, he is closely identified with Jazz Hot, even today.[when?].

Delaunay, who spent World War II years in Paris, had been following developments in progressive jazz, namely bebop and cool jazz. Delaunay also saw economic potential given that jazz in post-war France was big. Delaunay had been speaking of tolerance for modern jazz and "old white traditionalist" such as Eddie Condon and Jack Teagarden.

Jazz is more than just Dixieland or just re-bop...It's both of them and more.

Panassié, who through November 1946, had been editor-in-chief of Jazz Hot and President of the Hot Club of France, was furious over Delaunay's views in support for new jazz and threw him out as Secretary General of the Hot Club. Panassié declared a schism in the Association of Hot Clubs movement. A few regional clubs sided with Panassié but the Hot Club in Paris sided with Delaunay.

In November 1946, Delaunay, André Hodeir, and Frank Ténot formally declared Jazz Hot's independence from Hot Club. In December 1946 (Issue No. 11), the cover featured a full-page photo of Dizzy Gillespie and the erstwhile words on the cover, "Revue du Hot Club de France," disappeared. Henceforth, Delaunay was the publisher, Hodeir, editor-in-chief, Ténot, editorial secretary, and Jacques Souplet (fr), director. Jazz Hot's registered office was 14, rue Chaptal (fr), Paris 9e[a] Delaunay remained as the financial backer for 34 years — until 1980.

Jazz scholar Andy Fry wrote that the dispute was less about traditional jazz versus modern than it was about closed and open notions of jazz tradition, and it involved a "healthy slice of professional jealousy."[23] Jazz Scholar Matthew F. Jordan wrote that the split had begun not over whether jazz was a threat to true French culture, but over authority over the definition of jazz and commercial control of what had become a popular and marketable form of mass culture.[24]

Nonetheless, privatizing Jazz Hot and establishing a new openness to evolving jazz redefined the publication as a comprehensive jazz magazine — expanding its coverage in multiple countries and cities, rather than maintaining the erstwhile fan club publication of a revivalist niche style of jazz, for which a prime locus — a hotbed for a latent genre — was France.

In December 1946, Panassié resigned as editor-in-chief of Jazz Hot, claiming that "our correspondent in the United States, Franck Bauer (fr), was used to compare Bunk Johnson to Louis Armstrong!"[25] Jazz Hot — beginning with December 1946 issue, Vol. 12, No. 11 — removed Panassié's name as director from the masthead.

Bebop and cool

[edit]Beginning December 1946 (Issue No. 11), Jazz Hot began to add coverage of evolving jazz, which at the time consisted of so-called progressive jazz — bebop from New York, cool from Los Angeles, gypsy from France. Notable contributors included Lucien Malson (fr) (born 1926) and André Hodeir (1921–2011). Other influential magazines, notably Down Beat of Chicago, had been publishing articles that extoled bebop as serious music since 1940. Down Beat had risen through the 1940s on the tide of big band swing, which declined in the late 1940s. Bebop, however, continued to develop and spread globally into a jazz mainstay but has never been big in a commercial sense.[26][27][28]

Roscoe Seldon Suddarth, once an American diplomat, wrote a masters thesis, "French Stewardship of Jazz: The Case of France Musique and France Culture." In it, he stated that the French never developed a strong taste for white swing bands such as Glenn Miller, Tommy Dorsey, and Benny Goodman. He and other historians attribute this to the fact that the French were cut off from American music during the war. And also, the French developed a preference — strongly expressed by Panassié, Delaunay, and Vian — for African American musicians. Brubeck, popular in America, never caught on in France. His use of formal music training in jazz offended Hodier and Delaunay. According to Suddarth, Vian was so offended by it that he refused to distribute Brubeck's recordings, and for similar reasons he refused to distribute Stan Kenton's.[29]

Jazz,[30] a magazine published by the Hot Club of Belgium, ran from March to November 1945, Issues 1 through 13. After a one-month hiatus, it resumed in January 1946 under the name Hot Club Magazine: revue illustrée de la musique de jazz[31] and ran to August 1948, Issues 1 through 29. Carlos de Radzitzky (fr) (1915–1985) was editor-in-chief of Hot Club Magazine. Beginning November 1948, the publication was absorbed and appeared as a two-page insert in Jazz Hot from November 1948 to October 1956.[32] The Hot Club of Belgium was founded April 1, 1939, by Willy De Cort, Albert Bettonville (1916–2000), Carlos de Radzitzky, and others. The club disbanded in the mid-1960s.[33]

In October 1947, Boris Vian, a Sartre protégé, contributed an article to Combat, a leftist daily underground newspaper established in 1943, mocking Panassié[24][34][35] In 1947, Delaunay co-edited some essays called "Jazz 47" that were published in a special edition of the French publication, America. The article appeared under the auspices of the Hot Club of Paris but apparently without getting approval from the club. It included essays by Sartre, Robert Goffin, and Panassié, but Panassié was not invited to be an editor.[36]

Jazz Hot greeted the arrival of free jazz scene in New York and the European free jazz movement with much fanfare, devoting considerable space to the movement beginning in 1965 and throughout the peak of free jazz from about 1968 to 1972. Critics included Yves Buin (fr) (born 1938), Michel Le Bris (fr) (born 1944), Guy Kopelowicz, Bruno Vincent, and Philippe Constantin (fr) (1944–1996).[37]

Beginning with Issue No. 647, November 2008, Jazz Hot went online.

Related publications

[edit]Panassié started La Revue Du Jazz (fr): "Organe Officiel Du Hot Club De France," in January 1949 (Issue Issue No. 1) (OCLC 173877110, 4979636, 19880297). He was editor-in-chief. Bulletin Du Hot Club De France was started January 1948 (ISSN 0755-7272, ISSN 1144-987X). As of January 2025, the publication has endured 77 years as the official magazine of the Hot Club of France.

Selected contributors

[edit]French language

[edit]- Boris Vian (1920–1959), a protégé of Jean-Paul Sartre, and a novelist, poet, playwright, songwriter, jazz trumpeter, screenwriter, and actor, made his first contribution to Revue du Hot Club de France March 1946, Issue No. 5. A 1994 New York Times article stated that, "like many old-time French fans, Vian thought a white person could not play jazz, except for French white persons."[38] Outside of Jazz Hot, Vian published works under twenty-seven pseudonyms, and translated a great deal of American fiction, including works by Richard Wright, Raymond Chandler, and Ray Bradbury.[39]

- Marcel Zanini (born 1923)

- Frank Ténot (1925–2004), one of the critics who, in 1946 with Vian, began to question Panassié's nostalgic definition of jazz[24]

- Lucien Malson (born 1926)

- Carlos de Radzitzky (1915–1985), a Belgian music critic

- Pierre Nourry, one of the original contributors in 1936. In 1934, Panassié and Nourry, both co-founders of the Hot Club of France became President and Secretary General, respectively, of the club; Nourry, an impresario, is credited for inviting, in 1934, Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli to form the Quintette du Hot Club de France with Reinhardt's brother Joseph Reinhardt and Roger Chaput on guitar, and Louis Vola on bass,[9] when all of them were virtually unknown.[ii]

- Jacques Bureau (SOE) (1912–2008) was one of the original contributors in 1936 and was also a co-founder of the Hot Club of France.

- Franck Bergerot, journalist with Jazz Hot, 1979 to 1980 and 1984 to 1989

- Arnaud Merlin (born 1963) was a journalist at Jazz Hot beginning in the mid to late 1980s

- Albert Bettonville (1916–2000), co-founder of the Hot Club of Belgium, was, with Radzitzky, the most important Belgian jazz critic[40]

- Lucien Malson (born 1926) wrote for Jazz Hot from 1946 to 1956

- Jacques Demêtre (né Dimitri Wyschnegradsky; born 1924 Paris), Frenchified his name to Dimitri Vicheney but wrote under the pseudonym Jacques Demêtre (his father was composer Ivan Wyschnegradsky). He is one of the earliest musicologists in the world to analyze Chicago blues artists. Some historians credit him as the discoverer of post-war Chicago blues. His articles on Chicago blues spanned from the 1960s to the 1970s. He left Jazz Hot in the 1970s and later contributed to Soul Bag[8]

- Jean-Christophe Averty (born 1928), who works primarily in radio and TV, wrote some articles for Jazz Hot, notable two about Sidney Bechet in May 1960 and May 1969

- Laurent Goddet was a prolific contributor, notable articles include one 1976, "Free Blues: Don Pullen;"[b] His father was Jacques Goddet, sports journalist and director of Tour de France from 1936 to 1986

- Jacques D. LaCava, PhD, researched Chicago blues and wrote and produced the 1986 French documentary film, Sweet Home Chicago

English language

[edit]- Stanley Dance (1910–1999), who had been profoundly influenced by Panassié, wrote an article on Teddy Wilson in the first issue of Jazz Hot in March 1935; in 1946, he married Helen Oakley, Jazz Hot's correspondent in the U.S.; from 1948 until his death in 1999, he wrote for the Jazz Journal; in the 1950s he coined the term mainstream to describe those in between revivalist and modern, or alternatively between Dixieland and bebop

- John Hammond (1910-1987)

- George Frazier (1911–1974)

- Walter Schaap (né Walter Eliott Schaap; 1917–2005) became a committed follower of jazz while an undergraduate at Columbia University; in 1937, he studied at Sorbonne; while there, he collaborated with Panassié and Delaunay; his son, Phil Schaap (1951–2021), was a jazz host on WKCR in New York City.[41] Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet, the first classical music professional to take jazz seriously, wrote a seminal article in 1919, "Sur un Orchestre de Négre," in the October 1, 1919, issue of La Revue Romande. Nineteen years later, Jazz Hot published it in French and English; Schaap translated it to English.[c]

- Leonard Feather (1914–1994)

- Preston Jackson (1902–1983) wrote a regular column for Jazz Hot in the 1930s

- Ira Gitler (1928–2019)

Editors in chief

[edit]- Hugues Panassié: 1935–1939 & 1945–1946

- Panassié sought to define "true jazz" for France as being strictly Dixieland. To that end, he ridiculed some of the leading jazz musicians of his time. Panassié also ardently expressed the view that jazz played by whites was artificial jazz, though he lauded a few whites for their ability to replicate "true jazz." When he wrote of white jazz musicians, he often pointed out that they were white. As a result, he was sometimes criticized for stoking a reverse discrimination. Panassié resigned under pressure as editor-in-chief, but he had a following and continued to lead the anti-bebop wing of the French establishment.[42][43][d][44][45]

- André Hodeir: 1947–1951

- Hodeir was an early French proponent of bebop. DownBeat called Hodeir's first compilation of jazz writings, written in the early 1950s, Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence, "the best analytical book on jazz ever written."[46]

- fr:Jacques Souplet (fr):195?–1954

- Souplet left the magazine in 1954 to work for Barclay Records. He founded Jazz Magazine to make sure Barclay's new releases would be reviewed — Jazz Hot had been ignoring many of them.[38]

- Philippe Koechlin (fr): 1965–1968

- Koechlin started as a columnist for Hot Jazz in 1958. As editor, Koechlin published of 30,000 copies of a special issue of Jazz Hot in the summer of 1966, titled "Rock & Folk," which featured a photo of Bob Dylan on the cover and contained articles about the Rolling Stones, Antoine, Chuck Berry, Nino Ferrer, and Eddy Mitchell.[47] In the 1960s, it became difficult for Jazz Hot to keep up with the developments in New York.[e]

- Michel Le Bris (fr): 1968-1969

- Le Bris had been a protégé of Delaunay. His authority had been sharply curtailed late 1968 by Delaunay, who became alarmed that the magazine had become too political. Le Bris was, at the time, a member of Gauche prolétarienne and was sympathetic to protests. Le Bris was fired in December 1969, but went on to become editor of Gauche prolétarienne's publication, La Cause du Peuple (fr).[47]

- Yves Sportis: 1982??–19??

- Sportis moved the head office from Paris to Marseille.

- Jean-Claude Cintas: 1988–1990

Extant copies and archival access

[edit]Worldcat

Fédération internationale des hot clubs.; Hot Club de France.

Jazz Hot/Editions de L'Instant

Jazz-Diffusion

Unnamed publisher

L'Annuaire du jazz; supplément de la revue Jazz-hot

Library of Congress

National Library of France

Earlier jazz magazines

[edit]- La Revue du Jazz (fr) was first published in Paris July 1929, Issue No. 1, by an Armenian eccentric dancer and impresario, Grégor (né Krikor Kelekian; 1898–1971), who, beginning 1928, also led a jazz orchestra with Stéphane Grappelli at the piano.[48] It was the first French magazine to focus exclusively on jazz, but also served to promote his Grégor's big band. The magazine lasted for less than a year, ending March 1930, Issue No. 9. Panassié contributed two articles to this series.

- Review Négre (fr) was founded in 1925 in Paris, partly to promote the success in France of performances by Josephine Baker. The magazine is often cited as the first French jazz magazine, though its focus was not exclusively on jazz.

- Jazz-Tango was founded in Paris October 1930, Issue No. 1, and ran monthly until 1938. The magazine was published monthly and targeted professional musicians in dance bands that played jazz and Argentine tango. The magazine published the official news for the Hot Club of France until Panassié and Delaunay founded Jazz Hot in 1936. For a few publications, beginning around 1933, Jazz-Tango was renamed Jazz-Tango Dancing. In 1936, Jazz-Tango merged with L'orchestre L'orchestre, Jazz-Tango beginning with the May–June 1936 issue, No. 67. The editor of Jazz-Tango asked Panassié to become a columnist. The publication was a monthly and targeted professional musicians in dance bands. When approximately three-thousand Parisian musicians were out of work, a riff developed over Panassié declarations that true was had to be performed by black musicians. Stéphane (Marcel) Mougin (1909–1945), a pianist with the Gregor Orchestra and musicians' union organizer, contributed articles that ran counter to Panassié, in support of French musicians. Mougin was editor of La Revue du Jazz and Jazz-Tango. Notable contributors included Jacques Canetti, who had a job writing for Melody Maker. Léon Fiot, a musician, was one of the editors of Jazz-Tango.

- Der Jazzwereld, a Dutch publication, was founded by Ben Bakema (artist name Red. R. Dubroy), who published the first issue in August 1931.

- Down Beat was founded in Chicago in June 1934.

- Síncopa y Ritmo, an Argentine publication, was founded in Buenos Aires in August 1934.

- Gramophone which, as a general music magazine, included some jazz writing by critic Edgar Jackson

- Melody Maker was founded in 1926, which, at the time, mostly targeted dance band musicians

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ According to Scott DeVeaux, the "jazz as high art" movement did not reach its zenith until the 1950s, when a scholarly and journalistic effort was made to classify bebop as a legitimate art form, placing bebop at the peak of a stylistic evolution. ("Caught Between Jazz and Pop: The Contested Origins, Criticism, Performance Practice, and Reception of Smooth Jazz," doctorate dissertation, by Aaron J. West, PhD, University of North Texas, 2008; OCLC 464575154)

Citations from Jazz Hot

- ^ Cover: "Jack Diéval" (fr), Jazz Hot, Vol. 17, Second Series, November 1947

- ^ "Free Blues: Don Pullen" (translated by Mike Bond), Jazz Hot, Issue N° 331, October 1976

- ^ "Sur un Orchestre Négre," by Ernest Ansermet, translated by Schaap, Jazz Hot, Vol. 4, Issue N° 28, November–December 1938, pps. 4–8

- ^ "Préjugés" (translated by Jean-Jacques Finsterwald), Jazz Hot, Issue N° 45, June 1950, pg. 11

- ^ "Courrier" (Letters to the Editor), by Alain Lejeune, Jazz Hot, Issue N° 207, March 1965, pps. 15–16

Secondary sources

- ^ Blowin' Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics, by John Remo Gennari, PhD (born 1960), University of Chicago Press (2006), pg. 58; OCLC 701053921

- ^ a b Making Jazz French: Music and Modern Life in Interwar Paris (2nd printing), Duke University Press, by Jeffrey H. Jackson (2004), pg. 160; OCLC 265091395

- ^ "Jazz Periodicals: Greenwood Press, 1930–1970," Center for Research Libraries Reference Folder

- ^ "Hot Club de France," Oxford Music Online; OCLC 219650052, 644475451

- ^ Charles Delaunay et le Jazz en France dans les années 30-40 (Charles Delaunay and the Jazz in France in the Years 30–40; in French, adopted from Legrand's 2005 doctoral dissertation; OCLC 723055178, 552534701), by Anne Legrand, PhD, Éditions du Layeur (2009), pg. 239; OCLC 629704167

- ^ "French Critics and American Jazz," by David Strauss, Notes, Autumn 1965; pps. 583–587

- ^ " Le Hot — The Assimilation of American Jazz in France, 1917–1940," by William H. Kenney III (born 1940), Mid-America American Studies Association, Vol. 25, No. 1, Spring 1984, pps. 5–24

- ^ a b "Four Decades of French Blues Research in Chicago: From the Fifties Into the Nineties," by André J.M. Prévos, Black Music Research Journal, Vol. 12, No. 1, Spring 1992, pps. 97–112

- ^ a b c Django: The Life and Music of a Gypsy Legend, by Michael Dregni, Oxford University Press (2004); OCLC 62872303

- ^ "Louis Armstrong — A Rhapsody on Repetition and Time," by Jeffrey W. Robbins, from the book, The Counter-Narratives of Radical Theology and Popular Music: Songs of Fear and Trembling, Mike Grimshaw (ed.), Palgrave Macmillan (2014), pg. 95; OCLC 870285614

- ^ Bourbon Street Black; the New Orleans Black Jazzman, by Jack V. Buerkle & Danny Barker, Oxford University Press (1973); OCLC 694101

- ^ Le Jazz Hot (the book), by Hugues Panassié, Éditions Correa (fr) (1934); OCLC 906165198

- ^ "Jazz," Race and Racism in the United States ("Jazz" is in Vol. 2 of 4), Charles Andrew Gallagher (born 1962) & Cameron D. Lippard (eds.), Greenwood Press (2014), pg. 628; OCLC 842880937

- ^ The Real Jazz (1st ed.), by Hugues Panassié, Smith & Durrell, Inc. (1942); OCLC 892252

- ^ "Doubleness and Jazz Improvisation: Irony, Parody, and Ethnomusicology," by Ingrid Monson, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 20, No. 2, Winter, 1994, pps. 283–313; OCLC 729035395, 208728269, ISSN 0093-1896

- ^ "'Moldy Figs' and Modernists: Jazz at War (1942–1946)," by Bernard Gendron, Jazz Among the Discourses, Krin Gabbard (ed.), Duke University Press (1995), pg. 52 of pps. 31–56 (see end note 11); OCLC 31604682

- ^ "Canassié, Delaunay et Cie" (Chapter 1), American Musicians, by Whitney Balliett, Oxford University Press (1986)

- ^ "Decazeville. Gironde a Attiré Près de 150 Personnes," La Dépêche du Midi, October 4, 2013

- ^ Discography (possible reference, not confirmed): Musicraft 518 (Catalog No.), Side A: "Salt Peanuts," Matrix (on label): G565, Recorded May 11, 1945, New York City, Cross Reference Guild 1003:Dizzy Gillespie and His All-Star Quintet: Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Al Haig, Curly Russell, Sidney Catlett

- ^ Swing Under the Nazis: Jazz as a Metaphor for Freedom, by Mike Zwerin, First Cooper Square Press (2000), pg. 135; OCLC 44313406

- ^ "Delaunay On First Visit to America," by Bill Gottlieb, Down Beat Vol. 13, No. 18, August 26, 1946, pg. 4

- ^ More Important Than The Music: A History of Jazz Discography, by Bruce D. Epperson (born 1957), University of Chicago Press (2013), pg. 57; OCLC 842307572

- ^ "Remembrance of Jazz Past: Sidney Bechet in France," by Andy Fry, PhD, The Oxford Handbook of the New Cultural History of Music, Jane F. Fulcher (ed.), Oxford University Press (2011), pg. 314 of pps. 307–331; OCLC 632228317, 5104771002, 808062796

- ^ a b c Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity, by Matthew F. Jordan, University of Illinois Press (2010), pg. 238; OCLC 460058062

- ^ Delaunay's Dilemma: De La Peinture Au Jazz, by Charles Delaunay, Mâcon: Editions W (1985), pg. 161; OCLC 17411790, 842166067

- ^ "On the Corner: The Sellout of Miles Davis," by Stanley Crouch (1986), from the book, Reading jazz: A Gathering of Autobiography, Reportage, and Criticism From 1919 to Now, Robert Gottlieb (ed.), Pantheon Books (1995); OCLC 34515658

- ^ "Comparing the Shaming of Jazz and Rhythm and Blues in Music Criticism," by Matthew T. Brennan, PhD, University of Stirling (2007)

- ^ "About Down Beat, A History As Rich As Jazz Itself," Down Beat (2007), pg. 7 (retrieved May 19, 2015)

- ^ French Stewardship of Jazz: The Case of France Musique and France Culture (master thesis), by Roscoe Seldon Suddarth (1935–2013), University of Maryland (2008); OCLC 551767714

- ^ OCLC 1789466, 183295612

- ^ OCLC 5358361, 780289758, ISSN 2033-8694

- ^ "Les Annes-Lumiere (1940–1960)" (chapter 3), by Jean-Pol Schroeder, Dictionnaire du Jazz: à Bruxelles et en Wallonie, Pierre Mardaga (fr) (1991), pg. 36 (article: pps 27–44); OCLC 30357595

- ^ "Hot Club de Belgique," by Robert Pernet (de) (1940–2001), Grove Music Online (retrieved June 17, 2015); OCLC 5104954637

- ^ "Book Review: Le Jazz: Jazz and French Cultural Identity," by Bruce Boyd Raeburn, PhD: The Communication Review, Vol. 15, N°1, 2012, pps. 72–75; ISSN 1071-4421

- ^ "Le jazz en France," by Boris Vian, Combat, October 23, 1947

- ^ "Jazz 47," Robert Goffin & Charles Delaunay (eds.), America (periodical, special edition), Paris: Éditions Seghers (fr), N° 5, March 1947; OCLC 491593078, 858132265, ISSN 2018-5693

Essays:

c) Other and artwork by Jean Dubuffet and Félix Labisse

1. "Nick's Bar," by Jean-Paul Sartre

2. Jean Cocteau

3. Frank Ténot

4. "Origins of Jazz and Jazz and Surrealism, by Robert Goffin

5. "Jazz Greats," by Hugues Panassié

6. "Méfie de l’orchestre" ("Beware of the Orchestra"), by Boris Vian

Design, artwork, and photos:

a) Lithographic plate by Fernand Léger

b) Photos by Jean-Louis Bédoin

- ^ Music and the Elusive Revolution: Cultural Politics and Political Culture in France, 1968–1981 by Eric Drott, University of California Press (2011), pps. 118–119; OCLC 748593760

- ^ a b "An Empire Built on Jazz," by Mike Zwerin, New York Times, November 23, 1994

- ^ "Prince of Saint-Germain: How Boris Vian Brought Cool to Paris," by Daniel Halpern (born 1945), New Yorker, December 25, 2006, pps. 134–138, and January 1, 2007, pg. 134; OCLC 203857235, 230879652, ISSN 0028-792X

- ^ "Visiting Firemen 18: Louis Mitchell", by Robert Pernet and Howard Rye, Storyville, 2000–2001, pg. 243 (article: pps. 221–248); ISSN 0039-2030

- ^ Best Music Writing 2009, by Daphne Carr & Greil Marcus, Da Capo Press (2009), pg. 52; OCLC 316825636

- ^ Chasin' the Bird: The Life and Legacy of Charlie Parker, by Brian Priestley, Oxford University Press (2006); OCLC 61479676

- ^ "Beyond Le Boeuf: Interdisciplinary Rereadings of Jazz in France" (reviews), by Andy Fry, Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 128, No. 1, 2003, pps. 137–153; OCLC 4641333338, 5548341388; ISSN 0269-0403

Review of:Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story between the Great Wars, Music of the African Diaspora, by William A. Shack, University of California Press (2001); OCLC 45023134Le tumulte noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900–1930, by Jody Blake, Pennsylvania State University Press (1999); OCLC 37373655New Orleans sur Seine: Histoire dujazz en France, by Ludovic Tournès, Librairie Artheme Fayard (1999); OCLC 41506608 - ^ Down Beat, March 9, 1951, pg. 10

- ^ The Rise of a Jazz Art World, by Paul Douglas Lopes, Cambridge University Press (2002)

- ^ The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz, Leonard Feather & Ira Gitler (eds.), Oxford University Press (1999), pg 92; OCLC 38746731

- ^ a b "East Meets West at Jazz Hot: Maoism, Race, and Revolution in French Jazz Criticism," by Tad Shull (né Thomas Barclay Shull, Jr.; born 1955), Jazz Perspectives, Vol. 8, No. 1, April 2014, pps. 25–44; OCLC 5686458242, 5688435200, 5712619757, ISSN 1749-4060

- ^ Stephane Grappelli: A Life In Jazz, by Paul Balmer, Bobcat Books (2010), pg. 59; OCLC 227278674