Luxembourg in World War II

The involvement of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg in World War II began with its invasion by German forces on 10 May 1940 and lasted beyond its liberation by Allied forces in late 1944 and early 1945.

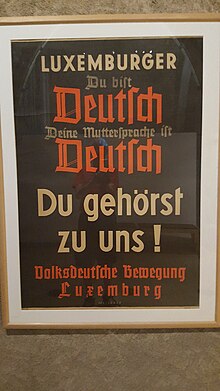

Luxembourg was placed under occupation and was annexed into Germany in 1942. During the occupation, the German authorities orchestrated a programme of "Germanisation" of the country, suppressing non-German languages and customs and conscripting Luxembourgers into the Wehrmacht, which led to extensive resistance, culminating in a general strike in August 1942 against conscription. The Germanisation was facilitated by a collaborationist political group, the Volksdeutsche Bewegung, founded shortly after the occupation. Shortly before the surrender, the government had fled the country along with Grand Duchess Charlotte, eventually arriving in London, where a Government-in-exile was formed. Luxembourgish soldiers also fought in Allied units until liberation.

Background

[edit]The Luxembourg government had pursued a policy of neutrality since the Luxembourg Crisis of 1867 had highlighted the country's vulnerability.[1] During the First World War, the 400 men of the Corps des Gendarmes et Volontaires had remained in barracks throughout the German occupation.[2] In March 1939, in a speech to the Reichstag, Adolf Hitler promised that Luxembourg sovereignty would not be breached.[3]

The strength of the military was gradually increased as international tension rose during Appeasement and after Britain and France's declaration of war against Germany in September 1939. By 1940, the Luxembourg army numbered some 13 officers, 255 armed gendarmes and 425 soldiers.[4]

The popular English-language radio station Radio Luxembourg was taken off-air in September 1939, amid fears that it might antagonize the Germans.[5] Apart from that, normal life continued in Luxembourg during the Phoney War; no blackout was enforced and regular trains to France and Germany continued.[6]

In Spring 1940,[7] work began on a series of roadblocks across Luxembourg's eastern border with Germany. The fortifications, known as the Schuster Line, were largely made of steel and concrete.[8]

German invasion

[edit]

On 9 May 1940, after increased troop movements around the German border, the barricades of the Schuster Line were closed.

The German invasion of Luxembourg, part of Fall Gelb ("Case Yellow"), began at 04:35 on the same day as the attacks on Belgium and the Netherlands. An attack by German Brandenburgers in civilian clothes against the Schuster Line and radio stations was however repulsed.[9] The invading forces encountered little resistance from the Luxembourg military who were confined in their barracks. By noon, the capital city had fallen.

The invasion was accompanied by an exodus of tens of thousands of civilians to France and the surrounding countries to escape the invasion.[citation needed]

At 08:00, several French divisions crossed the frontier from the Maginot Line and skirmished with the German forces before retreating. The invasion cost 7 Luxembourg soldiers wounded, with 1 British pilot and 5 French Spahis killed in action.[10]

German occupation

[edit]Life under occupation

[edit]

The departure of the government left the state functions of Luxembourg in disorder.[11] An administrative council under Albert Wehrer was formed in Luxembourg to attempt to reach an agreement with the occupiers whereby Luxembourg could continue to preserve some independence while remaining a Nazi protectorate, and called for the return of the Grand Duchess.[11] All possibility of compromise was eventually lost when Luxembourg was effectively incorporated into the German Gau Koblenz-Trier (renamed Gau Moselland in 1942) and all its own government functions were abolished from July 1940, unlike occupied Belgium and the Netherlands which preserved their state functions under German control.[11] From August 1942, Luxembourg was officially made part of Germany.[12]

From August 1940, speaking French was forbidden by proclamation of Gustav Simon in order to encourage the integration of the territory into Germany, proclaimed by posters carrying the slogan "Your language is German and only German"[note 1][13] This led to a popular revival of the traditional Luxembourgish language, which had not been prohibited, as a form of passive resistance.[14]

From August 1942, all male Luxembourgers of draft age were conscripted into the German armed forces.[15] Altogether, 12,000 Luxembourgers served in the German military, of whom nearly 3,000 died during the war.[14]

Collaboration

[edit]The most significant collaborationist group in the country was the Volksdeutsche Bewegung (VdB). Formed by Damian Kratzenberg shortly after the occupation, the VdB campaigned for the incorporation of Luxembourg into Germany with the slogan "Heim ins Reich" ("Home to the Reich"). The VdB had 84,000 members at its height, but coercion was widely exercised to encourage enlistment.[16] All manual workers were forced into the German Labour Front (DAF) from 1941 and certain age groups of both genders were conscripted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) to work on military projects.[16]

Membership of the Nazi youth movement, the "Luxemburger Volksjugend" (LVJ), which had been created with little success in 1936, was encouraged and it later merged into the Hitler Youth.[16]

Resistance

[edit]

Armed resistance to the German occupiers began in winter 1940–41 when a number of small groups were formed across the country.[17] Each had differing political objectives and some were directly affiliated to pre-war political parties, social groups (like the Scouts) or groups of students or workers.[17] Because of the small size of the pre-war Luxembourgish military, weapons were difficult to come by and so the resistance fighters were rarely armed until much later in the war.[17] Nevertheless, the resistance was heavily involved in printing anti-German leaflets and, from 1942, hiding "Réfractaires" (those avoiding German military service) in safe houses, and in some cases providing networks to escort them out of the country safely.[17] One Luxembourger, Victor Bodson (who was also a minister in the Government in Exile), was awarded the title Righteous Among the Nations by the State of Israel for helping about 100 Jews escape from Luxembourg during the occupation.[18]

Information gathered by the Luxembourgish resistance was extremely important. One Luxembourgish resistant, Léon-Henri Roth, informed the allies of the existence of the secret Peenemünde Army Research Center on the Baltic coast, allowing the allies to bomb it from the air.[19]

In Autumn 1944, many resistance organizations merged to form the "Unio'n vun de Fräiheetsorganisatiounen" or Unio'n.[17]

In November 1944, a group of 30 Luxembourgish resistance members commanded by Victor Abens was attacked by Waffen SS soldiers in the castle at Vianden. In the battle which followed, 23 Germans were killed by the resistance, who only lost one man killed during the operation although they were forced to withdraw to Allied lines.[20]

Passive resistance

[edit]Non-violent passive resistance was widespread in Luxembourg during the period. From August 1940, the "Spéngelskrich" (the "War of Pins") took place as Luxembourgers wore patriotic pin-badges (depicting the national colours or the Grand duchess), precipitating attacks from the VdB.[21]

In October 1941, the German occupiers took a survey of Luxembourgish civilians who were asked to state their nationality, their mother tongue and their racial group, but contrary to German expectations, 95% answered "Luxembourgish" to each question.[22] The refusal to declare themselves as German citizens led to mass arrests.[15]

Conscription was particularly unpopular. On 31 August 1942, shortly after the announcement that conscription would be extended to all men born between 1920 and 1927, a strike began in the northern town of Wiltz.[17] The strike spread rapidly, paralysing the factories and industries of Luxembourg.[23] The strike was quickly repressed and its leaders arrested. 20 were summarily tried before a special tribunal (in German, a "Standgericht") and executed by firing squad at nearby Hinzert concentration camp.[17] Nevertheless, protests against conscription continued and 3,500 Luxembourgers would desert the German army after being conscripted.[24]

Holocaust

[edit]

Before the war, Luxembourg had a population of about 3500 Jews, many of them newly arrived in the country to escape persecution in Germany.[12] The Nuremberg Laws, which had applied in Germany since 1935, were enforced in Luxembourg from September 1940 and Jews were encouraged to leave the country for Vichy France.[12] Emigration was forbidden in October 1941, but not before nearly 2500 had fled.[12] In practice they were little better off in Vichy France, and many of those who left were later deported and killed. From September 1941, all Jews in Luxembourg were forced to wear the yellow Star of David badge to identify them.[15]

From October 1941, Nazi authorities began to deport the around 800 remaining Jews from Luxembourg to Łódź Ghetto and the concentration camps at Theresienstadt and Auschwitz.[12] Around 700 were deported from the Transit Camp at Fuenfbrunnen in Ulflingen in the north of Luxembourg.[12]

Luxembourg was declared "Judenrein" ("cleansed of Jews") except for those in hiding[15] on 19 October 1941.[25] Only 36 of the Jewish population of Luxembourg to have been sent to concentration camps are known to have survived to the end of the war.[12]

Free Luxembourg Forces and the government-in-exile

[edit]

The Government in Exile first fled to Paris, then after the Fall of France, to Lisbon and then the United Kingdom.[11] While the Government established itself in Wilton Crescent in the Belgravia area of London, the Grand Duchess and her family moved to Francophone Montreal[26] in Canada.[11] The government in exile was vocal in stressing the Luxembourg cause in newspapers in allied countries and succeeded in obtaining Luxembourgish language broadcasts to the occupied country on BBC radio.[27] In 1944, the government in exile signed a treaty with the Belgian and Dutch governments, creating the Benelux Economic Union and also signed into the Bretton Woods system.[19]

Luxembourg's military involvement could play only a "symbolic role" for the allied cause,[19] and numerous Luxembourgers fought in allied armies. From March 1944, Luxembourg soldiers operated four 25 pounder guns, christened Elisabeth, Marie Adelaide, Marie Gabriele and Alix after the Grand duchess' daughters, as part of C Troop, 1st Belgian Field Artillery Battery of the 1st Belgian Infantry Brigade, commonly known as the "Brigade Piron" after its commander Jean-Baptiste Piron.[28] The Troop numbered some 80 men.[2] The battery landed in Normandy with the Brigade Piron on 6 August 1944[2] and served in the Battle of Normandy and was involved in the Liberation of Brussels in September 1944.

Prince Jean, son of the Grand Duchess and future Grand Duke, served in the Irish Guards from 1942. He took part in the Battle of Caen, the liberation of Brussels, the liberation of Luxembourg, and Operation Market Garden.[29][30]

Liberation

[edit]

Luxembourg was liberated by Allied forces in September 1944. Allied tanks entered the capital city on 10 September 1944, where the Germans retreated without fighting. The Allied advance triggered the resistance to rise up: at Vianden, members of the Luxembourgish resistance fought a much larger German force at the Battle of Vianden Castle. In mid December, the Germans launched the "Ardennes Offensive" in Luxembourg and the Belgian Ardennes. Though the city of Luxembourg remained in Allied hands throughout, much of the north of the country was lost to German forces and had to be liberated again.[citation needed]

Gustav Simon, the Nazi Gauleiter responsible for Moselland and Luxembourg, fled but was captured and imprisoned by the British Army. He committed suicide in an Allied prison. In Luxembourg too, collaborators were imprisoned and tried. Damian Kratzenberg, founder and leader of VdB, was one of those executed for his role.[citation needed]

Two German V-3 cannon with a range of 40 km (25 mi) were used to bombard the city of Luxembourg from December 1944 until February 1945.[31]

Battle of the Bulge

[edit]Most of Luxembourg was rapidly liberated in September 1944 when the front line stabilized behind the Our and Sauer Rivers along the Luxembourg-German frontier. Following the campaign in Brittany, the U.S. VIII Corps occupied the sector of the front line in Luxembourg. On 16 December 1944, elements of the U.S. 28th and 4th Infantry Divisions, as well as a combat command of the 9th Armored Division were defending the line of the Our and Sauer Rivers when the German offensive started.[citation needed]

The initial defensive efforts of the U.S. troops hinged upon holding towns near the international frontier. As a result, the towns of Clervaux, Marnach, Holzthum, Consthum, Weiler, and Wahlhausen[32] were used as strongholds by the Americans and attacked by the Germans, who wanted to achieve control of the road networks in northern Luxembourg in order for their forces to move westward. After the Americans in northern Luxembourg were forced to retreat by the German attacks, the area experienced a second passage of the front line during January–February 1945, this time moving generally eastward as the U.S. Third Army attacked into the southern flank of the German penetration (the "Bulge"). Vianden was the final community in Luxembourg to be liberated on 12 February 1945.[32]

Because of the determination of both sides to prevail on the battlefield, the combat in Luxembourg was bitter and correspondingly hard on the civilian population. Over 2,100 homes in Luxembourg were destroyed in the fighting and more than 1,400 others seriously damaged. It is also estimated that some 500 Luxembourgish non-combatants lost their lives during the Battle of the Bulge.[33] Besides the dead, over 45,000 Luxembourgers became refugees during the battle.[citation needed]

Aftermath

[edit]The experience of invasion and occupation during the war led to a shift in Luxembourg's stance on neutrality.[34] Luxembourg signed the Treaty of Brussels with other western European powers on 17 March 1948 as part of the initial European postwar security cooperation and in a move that foreshadowed Luxembourg's membership in NATO. Luxembourg also began greater military co-operation with Belgium after the war, training soldiers together and even sending a joint contingent to fight in the Korean War in 1950.[citation needed]

Following the war, Luxembourgish troops took part in the occupation of West Germany, contributing troops that were part of the force in the French Zone, beginning in late 1945. Luxembourgish forces functioned under overall French command within the zone and were responsible for the areas of Bitburg and Eifel and parts of Saarburg. They were withdrawn from Saarburg in 1948, and from Bitburg-Eifel in July 1955.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Invasion of Luxembourg

- Luxembourg Resistance

- Luxembourg government-in-exile

- Luxembourgish collaboration with Nazi Germany

- German occupation of Luxembourg in World War II

- The Holocaust in Luxembourg

- Luxembourg annexation plans after the Second World War

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Eure Sprache sei deutsch und nur deutsch"

References

[edit]- ^ Various (2011). Les Gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF). Luxembourg: Government of Luxembourg. p. 110. ISBN 978-2-87999-212-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ a b c Gaul, Roland. "The Luxembourg Army". MNHM. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Office of United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality (1946). "9: Launching of Wars of Aggression, section 10 Aggression against Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg". Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression (1). United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 2013-09-27.

- ^ Thomas, Nigel (1991). Foreign Volunteers of the Allied Forces, 1939–45. London: Osprey. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-85532-136-6.

- ^ Fletcher, 2012, p.12

- ^ Fletcher, 2012, p.13

- ^ Buckton, Henry (2017-05-15). Retreat: Dunkirk and the Evacuation of Western Europe. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-6483-5.

- ^ Thomas, Nigel (2014-02-20). Hitler's Blitzkrieg Enemies 1940: Denmark, Norway, Netherlands & Belgium. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-598-8.

- ^ "2) Fall Gelb l'invasion du Luxembourg le jeudi 9 mai 1940 à 04h35" (in French). 28 December 2009. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- ^ Raths, Aloyse (2008). Unheilvolle Jahre für Luxemburg – Années néfastes pour le Grand-Duché. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Various (2011). Les Gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF). Luxembourg: Government of Luxembourg. pp. 110–1. ISBN 978-2-87999-212-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Luxembourg". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Fletcher, 2012, p.102

- ^ a b "World War II". Allo Expat: Luxembourg. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d "The Destruction of the Jews of Luxembourg". Holocaust Education and Archive Research Team. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Luxemburg Collaborationist Forces in During WWII". Feldgrau. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Heim in Reich: La 2e guerre mondiale au Luxembourg – quelques points de repère". Centre National de l'Audiovisuel. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "Righteous Among the Nations Honored by Yad Vashem: Luxembourg" (PDF). Yad Vashem. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b c Yapou, Eliezer (1998). "Luxembourg: The Smallest Ally". Governments in Exile, 1939–1945. Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Raths, Aloyse (2008). Unheilvolle Jahre für Luxemburg – Années néfastes pour le Grand-Duché. pp. 401–3.

- ^ Fletcher, Willard Allen (2012). Fletcher, Jean Tucker (ed.). Defiant Diplomat: George Platt Waller, American consul in Nazi-occupied Luxembourg 1939–1941. Newark: University of Delaware Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-61149-398-6.

- ^ Thewes, Guy (2011). Les Gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF). Luxembourg: Government of Luxembourg. p. 114. ISBN 978-2-87999-212-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-11. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ^ "Commémoration à l'occasion du 60e anniversaire de la grève générale du 31 août 1942". Government.lu. 31 August 2002. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "Luxembourg Volunteers in the German Wehrmacht in WWII". Feldgrau. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ "Commémoration de la Shoah au Luxembourg". Government.lu. 3 July 2005. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Bernier Arcand, Philippe (2010). "L'exil québécois du gouvernement du Luxembourg" (PDF). Histoire Québec. 15 (3): 19–26 – via Erudit.

- ^ Various (2011). Les Gouvernements du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg depuis 1848 (PDF). Luxembourg: Government of Luxembourg. p. 112. ISBN 978-2-87999-212-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- ^ "The 1st Belgian Field Artillery Battery, 1941–1944". Be4046.eu. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ Schaverien, Anna; Barthelemy, Claire (24 April 2019). "Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg is Dead at 98". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 Nov 2021.

- ^ "S.A.R. le Grand Duke Jean". Retrieved 22 Nov 2021.

- ^ "V-3: The High Pressure Pump Gun". Battlefieldsww2.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b "La bataille des Ardennes". Secondeguerremondiale.public.lu. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ Schrijvers, Peter (2005). The Unknown Dead: Civilians in the Battle of the Bulge. University Press of Kentucky. p. 361. ISBN 0-8131-2352-6.

- ^ "Luxemburg nach dem Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs". Histoprim Online. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Primary sources

- Fletcher, Willard Allen (2012). Fletcher, Jean Tucker (ed.). Defiant Diplomat: George Platt Waller, American consul in Nazi-occupied Luxembourg 1939–1941. Newark: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 978-1-61149-398-6.

- Secondary literature

- Grosbusch, André (1 October 1984). "La question des réparations dans l'opinion luxembourgeoise 1945-1949". Hémecht (in French). 36 (4): 569ff.

- Hoffmann, Serge (2002). "Les relations germano-luxembourgeoises durant les années 30" (PDF). Ons Stad (in French) (71): 2–4.

- Milmeister, Jean (1 April 2007), "Augenzeugen berichten über die Ardennenschlacht in Vianden", Hémecht (in German), vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 175–185, retrieved 29 October 2023

- Raths, Aloyse (2008). Unheilvolle Jahre für Luxemburg – Années néfastes pour le Grand-Duché. Luxembourg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Schaack, Albert; Verhoeyen, Etienne (1 July 2012), "L'espionnage allemand au Luxembourg avant la Deuxième Guerre mondiale (1936 - 1940)" [German espionage in Luxembourg before the Second World War (1936-1940)], Hémecht (in French), vol. 64, no. 3, pp. 73–116, retrieved 28 October 2023

- Streicher, Félix (1 July 2019). "Une drôle de petite armée in der drôle de guerre: Die luxemburgische Force Armée zwischen September 1939 und Mai 1940". Hémecht (in German). 71 (3): 279ff.