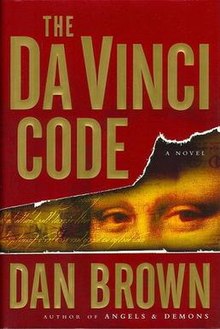

The Da Vinci Code

The first U.S. edition | |

| Author | Dan Brown |

|---|---|

| Series | Robert Langdon #2 |

| Genre | Mystery, detective fiction, conspiracy fiction, thriller |

| Publisher | Doubleday (US) |

Publication date | March 18, 2003[1] |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 689 (U.S. hardback) 489 (U.S. paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-385-50420-9 (US) |

| OCLC | 50920659 |

| 813/.54 21 | |

| LC Class | PS3552.R685434 D3 2003 |

| Preceded by | Angels & Demons |

| Followed by | The Lost Symbol |

The Da Vinci Code is a 2003 mystery thriller novel by Dan Brown. It is Brown's second novel to include the character Robert Langdon: the first was his 2000 novel Angels & Demons. The Da Vinci Code follows symbologist Langdon and cryptologist Sophie Neveu after a murder in the Louvre Museum in Paris entangles them in a dispute between the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei over the possibility of Jesus and Mary Magdalene having had a child together.

The novel explores an alternative religious history, whose central plot point is that the Merovingian kings of France were descended from the bloodline of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene, ideas derived from Clive Prince's The Templar Revelation (1997) and books by Margaret Starbird. The book also refers to The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (1982), although Brown stated that it was not used as research material.[2]

The Da Vinci Code provoked a popular interest in speculation concerning the Holy Grail legend and Mary Magdalene's role in the history of Christianity. The book has been extensively denounced by many Christian denominations as an attack on the Catholic Church, and also consistently criticized by scholars for its historical and scientific inaccuracies. The novel became a massive worldwide bestseller,[3] selling 80 million copies as of 2009[update],[4] and has been translated into 44 languages. In November 2004, Random House published a Special Illustrated Edition with 160 illustrations. In 2006, a film adaptation was released by Columbia Pictures.

Plot

[edit]Louvre curator and Priory of Sion grand master Jacques Saunière is fatally shot one night at the museum by an albino Catholic monk named Silas, who is working on behalf of someone he knows only as the Teacher, who wishes to discover the location of the "keystone", an item crucial in the search for the Holy Grail. After Saunière's body is discovered in the pose of the Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci, the police summon Harvard professor Robert Langdon, who is in town on business. Police captain Bezu Fache tells him that he was summoned to help the police decode the cryptic message Saunière left during the final minutes of his life. The message includes a Fibonacci sequence out of order and an anagram: "O, draconian devil! Oh, lame saint!" Langdon explains to Fache that the pentacle Saunière drew on his chest in his own blood represents an allusion to the goddess and not devil worship, as Fache believes.

Sophie Neveu, a police cryptographer, secretly explains to Langdon that she is Saunière's estranged granddaughter and that Fache thinks Langdon is the murderer because the last line in her grandfather's message, which was meant for Neveu, said "P.S. Find Robert Langdon", which Fache had erased prior to Langdon's arrival. However, "P.S." does not refer to "postscript", but rather to Sophie — the nickname given to her by her grandfather was "Princess Sophie". She understands that her grandfather intended Langdon to decipher the code, which leads to Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, which in turn leads to his painting Madonna of the Rocks. They find a pendant that holds the address of the Paris branch of the Depository Bank of Zurich.

Neveu and Langdon escape from the police and visit the bank. In the safe deposit box, which is unlocked with the Fibonacci sequence, they find a box containing the keystone: a cryptex, a cylindrical, hand-held vault with five concentric, rotating dials labeled with letters. When they are lined up correctly, they unlock the device, but if the cryptex is forced open, an enclosed vial of vinegar breaks and dissolves the message inside the cryptex, which was written on papyrus. The box containing the cryptex contains clues to its password.

Langdon and Neveu take the keystone to the home of Langdon's friend, Sir Leigh Teabing, an expert on the Holy Grail, the legend of which is heavily connected to the Priory. There, Teabing explains that the Grail is not a cup but connected to Mary Magdalene, and that she was Jesus Christ's wife and is the person to his right in The Last Supper. The trio then flee the country on Teabing's private plane, on which they conclude that the proper combination of letters spells out Neveu's given name, Sofia. Opening the cryptex, they discover a smaller cryptex inside it, along with another riddle that ultimately leads the group to the tomb of Isaac Newton in Westminster Abbey.

During the flight to Britain, Neveu reveals the source of her estrangement from her grandfather ten years earlier: arriving home unexpectedly from university, Neveu secretly witnessed a spring fertility rite conducted in the secret basement of her grandfather's country estate. From her hiding place, she was shocked to see her grandfather with a woman at the center of a ritual attended by men and women who were wearing masks and chanting praise to the goddess. She fled the house and broke off all contact with Saunière. Langdon explains that what she witnessed was an ancient ceremony known as hieros gamos or "sacred marriage".

By the time they arrive at Westminster Abbey, Teabing is revealed to be the Teacher for whom Silas is working. Teabing wishes to use the Holy Grail, which he believes is a series of documents establishing that Jesus Christ married Mary Magdalene and fathered children, in order to ruin the Vatican. He compels Langdon at gunpoint to solve the second cryptex's password, which Langdon realizes is "apple". Langdon secretly opens the cryptex and removes its contents before tossing the empty cryptex in the air. Teabing is arrested by Fache, who by now realizes that Langdon is innocent. Bishop Aringarosa, head of religious sect Opus Dei and Silas' mentor, realizing that Silas has been used to murder innocent people, rushes to help the police find him. When the police find Silas hiding in an Opus Dei Center, Silas assumes that they are there to kill him and he rushes out, accidentally shooting Bishop Aringarosa. Bishop Aringarosa survives but is informed that Silas was found dead later from a gunshot wound.

The final message inside the second keystone leads Neveu and Langdon to Rosslyn Chapel, whose docent turns out to be Neveu's long-lost brother, whom Neveu had been told died as a child in the car accident that killed her parents. The guardian of Rosslyn Chapel, Marie Chauvel Saint Clair, is Neveu's long-lost grandmother and Saunière's wife who was the woman who participated with him in the "sacred marriage". It is revealed that Neveu and her brother are descendants of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene. The Priory of Sion hid her identity to protect her from possible threats to her life. The real meaning of the last message is that the Grail is buried beneath the small pyramid directly below La Pyramide Inversée, the inverted glass pyramid of the Louvre. It also lies beneath the "Rose Line", an allusion to "Rosslyn". Langdon figures out this final piece to the puzzle; he follows the Rose Line (prime meridian) to La Pyramide Inversée, where he kneels to pray before the hidden sarcophagus of Mary Magdalene, as the Templar knights did before.

Characters

[edit]

|

|

Reaction

[edit]Sales

[edit]The Da Vinci Code was a major success in 2003, outsold only by J. K. Rowling's Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix.[5] As of 2016, it had sold 80 million copies worldwide.[6]

Historical inaccuracies

[edit]

The Da Vinci Code generated criticism when it was first published for the fictitious description of the core aspects of Christianity and descriptions of European art, history, and architecture. The book has received negative reviews mostly from Catholic and other Christian communities. Many critics took issue with the level of research Brown did when writing the story. The New York Times writer Laura Miller characterized the novel as "based on a notorious hoax", "rank nonsense", and "bogus", saying the book is heavily based on the fabrications of Pierre Plantard, who is asserted to have created the Priory of Sion in 1956.[7]

Critics accuse Brown of distorting and fabricating history. Theological author Marcia Ford considered that novels should be judged not on their literary merit, but on their conclusions:

Regardless of whether you agree with Brown's conclusions, it's clear that his history is largely fanciful, which means he and his publisher have violated a long-held if unspoken agreement with the reader: Fiction that purports to present historical facts should be researched as carefully as a nonfiction book would be.[8]

Richard Abanes wrote:

The most flagrant aspect ... is not that Dan Brown disagrees with Christianity but that he utterly warps it in order to disagree with it ... to the point of completely rewriting a vast number of historical events. And making the matter worse has been Brown's willingness to pass off his distortions as 'facts' with which innumerable scholars and historians agree.[8]

Much of the controversy generated by The Da Vinci Code was due to the fact that the book was marketed as being historically accurate; the novel opens with a "fact" page that states that "The Priory of Sion—a French secret society founded in 1099—is a real organization", whereas the Priory of Sion is a hoax created in 1956 by Pierre Plantard, which Plantard admitted under oath in 1994, well before the publication of The Da Vinci Code.[9] The fact page itself is part of the novel as a fictional piece, but is not presented as such. The page also states that "all descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents ... and secret rituals in this novel are accurate", a claim disputed by numerous academic scholars and experts in numerous areas.[10]

Brown addressed the idea of some of the more controversial aspects being fact on his website, stating that the page at the beginning of the novel mentions only "documents, rituals, organization, artwork and architecture" but not any of the ancient theories discussed by fictional characters, stating that "Interpreting those ideas is left to the reader". Brown also says, "It is my belief that some of the theories discussed by these characters may have merit" and "the secret behind The Da Vinci Code was too well documented and significant for me to dismiss."[11]

In 2003, while promoting the novel, Brown was asked in interviews what parts of the history in his novel actually happened. He replied "Absolutely all of it."[12] In a 2003 interview with CNN's Martin Savidge he was again asked how much of the historical background was true. He replied, "99% is true... the background is all true".[13] Asked by Elizabeth Vargas in an ABC News special if the book would have been different if he had written it as non-fiction he replied, "I don't think it would have."[14]

In 2005, UK TV personality Tony Robinson edited and narrated a detailed rebuttal of the main arguments of Brown and those of Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln, who authored the book Holy Blood, Holy Grail, in the program The Real Da Vinci Code, shown on British TV Channel 4. The program featured lengthy interviews with many of the main protagonists cited by Brown as "absolute fact" in The Da Vinci Code. Arnaud de Sède, son of Gérard de Sède, stated categorically that his father and Plantard had made up the existence of the Prieuré de Sion, the cornerstone of the Jesus bloodline theory: "frankly, it was piffle",[15] noting that the concept of a descendant of Jesus was also an element of the 1999 Kevin Smith film Dogma.

The earliest appearance of this theory is due to the 13th-century Cistercian monk and chronicler Peter of Vaux de Cernay who reported that Cathars believed that the 'evil' and 'earthly' Jesus Christ had a relationship with Mary Magdalene, described as his concubine (and that the 'good Christ' was incorporeal and existed spiritually in the body of Paul).[16] The program The Real Da Vinci Code also cast doubt on the Rosslyn Chapel association with the Grail and on other related stories, such as the alleged landing of Mary Magdalene in France.

According to The Da Vinci Code, the Roman Emperor Constantine I suppressed Gnosticism because it portrayed Jesus as purely human.[17] The novel portrays Constantine as wanting Christianity to act as a unifying religion for the Roman Empire, thinking that Christianity would appeal to pagans only if it featured a demigod similar to pagan heroes. According to the Gnostic Gospels, Jesus was merely a human prophet, not a demigod. Therefore, to change Jesus' image, Constantine destroyed the Gnostic Gospels and promoted the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which portray Jesus as divine or semi-divine; however, most scholars agree that all Gnostic writings depict Christ as purely divine, his human body being a mere illusion (docetism).[18] Gnostic sects saw Christ this way because they regarded matter as evil, and therefore believed that a divine spirit would never have taken on a material body.[19]

Literary criticism

[edit]The book received both positive and negative reviews from critics, and it has been the subject of negative appraisals concerning its portrayal of history. Its writing and historical accuracy were reviewed negatively by The New Yorker,[20] Salon.com,[21] and Maclean's.[22] On the May/June 2003 issue of Bookmarks, a magazine that aggregates critic reviews of books, the book received a ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() (4.0 out of 5) based on critic reviews with the critical summary stating, "Overall, this breezy, entertaining thriller will take you on an ingeniously conceived ride through history."[23][24][25]

(4.0 out of 5) based on critic reviews with the critical summary stating, "Overall, this breezy, entertaining thriller will take you on an ingeniously conceived ride through history."[23][24][25]

Positive

[edit]Janet Maslin of The New York Times said that one word "concisely conveys the kind of extreme enthusiasm with which this riddle-filled, code-breaking, exhilaratingly brainy thriller can be recommended. That word is wow. The author is Dan Brown (a name you will want to remember). In this gleefully erudite suspense novel, Mr. Brown takes the format he has been developing through three earlier novels and fine-tunes it to blockbuster perfection."[26] David Lazarus of The San Francisco Chronicle said, "This story has so many twists—all satisfying, most unexpected—that it would be a sin to reveal too much of the plot in advance. Let's just say that if this novel doesn't get your pulse racing, you need to check your meds."[27] The book appeared at number 43 on a 2010 list of 101 best books ever written, which was derived from a survey of more than 15,000 Australian readers.[28]

Disparaging

[edit]Stephen King likened Brown's work to "Jokes for the John", calling such literature the "intellectual equivalent of Kraft Macaroni and Cheese".[29] Roger Ebert described it as a "potboiler written with little grace and style", although he added it did "supply an intriguing plot".[30] In his review of the film National Treasure, whose plot also involves ancient conspiracies and treasure hunts, he wrote: "I should read a potboiler like The Da Vinci Code every once in a while, just to remind myself that life is too short to read books like The Da Vinci Code."[31] While interviewing Umberto Eco in a 2008 issue of The Paris Review, Lila Azam Zanganeh characterized The Da Vinci Code as "a bizarre little offshoot" of Eco's novel, Foucault's Pendulum. In response, Eco remarked, "Dan Brown is a character from Foucault's Pendulum! I invented him. He shares my characters' fascinations—the world conspiracy of Rosicrucians, Masons, and Jesuits. The role of the Knights Templar. The hermetic secret. The principle that everything is connected. I suspect Dan Brown might not even exist."[32]

Negative

[edit]Salman Rushdie said during a lecture, "Do not start me on The Da Vinci Code. A novel so bad that it gives bad novels a bad name."[33] Stephen Fry has referred to Brown's writings as "complete loose stool-water" and "arse gravy of the worst kind".[34] In a live chat on June 14, 2006, he clarified, "I just loathe all those book[s] about the Holy Grail and Masons and Catholic conspiracies and all that botty-dribble. I mean, there's so much more that's interesting and exciting in art and in history. It plays to the worst and laziest in humanity, the desire to think the worst of the past and the desire to feel superior to it in some fatuous way."[35] A. O. Scott, reviewing the movie based on the book for The New York Times, called the book "Dan Brown's best-selling primer on how not to write an English sentence".[36] The New Yorker reviewer Anthony Lane refers to it as "unmitigated junk" and decries "the crumbling coarseness of the style".[20] Linguist Geoffrey Pullum and others posted several entries critical of Brown's writing, at Language Log, calling Brown one of the "worst prose stylists in the history of literature" and saying Brown's "writing is not just bad; it is staggeringly, clumsily, thoughtlessly, almost ingeniously bad".[37]

Lawsuits

[edit]Author Lewis Perdue alleged that Brown plagiarized two of his novels, The Da Vinci Legacy, originally published in 1983, and Daughter of God, originally published in 2000. He sought to block distribution of the book and film. However, Judge George Daniels of the US District Court in New York ruled against Perdue in 2005, saying that "A reasonable average lay observer would not conclude that The Da Vinci Code is substantially similar to Daughter of God" and that "Any slightly similar elements are on the level of generalized or otherwise unprotectable ideas."[38] Perdue appealed; the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the original decision, saying Mr. Perdue's arguments were "without merit".[39]

In early 2006, Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh filed suit against Brown's publisher, Random House. They alleged that significant portions of The Da Vinci Code were plagiarized from The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, violating their copyright.[40] Brown confirmed during the court case that he named the principal Grail expert of his story Leigh Teabing, an anagram of "Baigent Leigh", after the two plaintiffs. In reply to the suggestion that Henry Lincoln was also referred to in the book, since he has medical problems resulting in a severe limp, like the character of Leigh Teabing, Brown stated he was unaware of Lincoln's illness and the correspondence was a coincidence.[41] Since Baigent and Leigh had presented their conclusions as historical research, not as fiction, Mr Justice Peter Smith, who presided over the trial, deemed that a novelist must be free to use these ideas in a fictional context, and ruled against Baigent and Leigh. Smith also hid his own secret code in his written judgment, in the form of seemingly random italicized letters in the 71-page document, which apparently spell out a message. Smith indicated he would confirm the code if someone broke it.[42] After losing before the High Court on July 12, 2006, Baigent and Leigh appealed to the Court of Appeal, unsuccessfully.[41][42]

In April 2006 Mikhail Anikin, a Russian scientist and art historian working as a senior researcher at the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, stated the intention to bring a lawsuit against Brown, maintaining that he was the one who coined the phrase used as the book's title and one of the ideas regarding the Mona Lisa used in its plot. Anikin interprets the Mona Lisa to be a Christian allegory consisting of two images, one of Jesus Christ that comprises the image's right half, and one of the Virgin Mary that forms its left half. According to Anikin, he expressed this idea to a group of experts from the Museum of Houston during a 1988 René Magritte exhibit at the Hermitage, and when one of the Americans requested permission to pass it along to a friend Anikin granted the request on condition that he be credited in any book using his interpretation. Anikin eventually compiled his research into Leonardo da Vinci or Theology on Canvas, a book published in 2000, but The Da Vinci Code, published three years later, makes no mention of Anikin and instead asserts that the idea in question is a "well-known opinion of a number of scientists".[43][44]

Brown has been sued twice in U.S. Federal courts by the author Jack Dunn who claims Brown copied a huge part of his book The Vatican Boys to write The Da Vinci Code and Angels & Demons. Neither lawsuit was allowed to go to a jury trial. In 2017, in London, another claim was begun against Brown by Jack Dunn who claimed that justice was not served in the U.S. lawsuits.[45] Possibly the largest reaction occurred in Kolkata, India, where a group of around 25 protesters "stormed" Crossword bookstore, pulled copies of the book from the racks, and threw them to the ground. On the same day, a group of 50–60 protesters successfully made the Oxford Bookstore on Park Street decide to stop selling the book "until the controversy sparked by the film's release was resolved".[46] Thus in 2006, seven Indian states (Nagaland, Punjab, Goa, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh) banned the release or exhibition of the Hollywood movie The Da Vinci Code (as well as the book).[47] Later, two states, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, lifted the ban under high court order.[48][49]

Release details

[edit]The book has been translated into over 44 languages, primarily hardcover.[50] Major English-language (hardcover) editions include:

- The Da Vinci Code (1st ed.), US: Doubleday, April 2003, ISBN 0-385-50420-9.

- The Da Vinci Code (spec illustr ed.), Doubleday, November 2, 2004, ISBN 0-385-51375-5 (as of January 2006, has sold 576,000 copies).

- The Da Vinci Code, UK: Corgi Adult, April 2004, ISBN 0-552-14951-9.

- The Da Vinci Code (illustr ed.), UK: Bantam, October 2, 2004, ISBN 0-593-05425-3.

- The Da Vinci Code (trade paperback), US/CA: Anchor, March 2006.

- The da Vinci code (paperback), Anchor, March 28, 2006, 5 million copies.

- The da Vinci code (paperback) (special illustrated ed.), Broadway, March 28, 2006, released 200,000 copies.

- Goldsman, Akiva (May 19, 2006), The Da Vinci Code Illustrated Screenplay: Behind the Scenes of the Major Motion Picture, Howard, Ron; Brown, Dan introd, Doubleday, Broadway, the day of the film's release. Including film stills, behind-the-scenes photos and the full script. 25,000 copies of the hardcover, and 200,000 of the paperback version.[51]

Film

[edit]Columbia Pictures adapted the novel to film, with a screenplay written by Akiva Goldsman, and Academy Award winner Ron Howard directing. The film was released on May 19, 2006, and stars Tom Hanks as Robert Langdon, Audrey Tautou as Sophie Neveu, and Sir Ian McKellen as Sir Leigh Teabing. During its opening weekend, moviegoers spent an estimated $77 million in America, and $224 million worldwide.[52]

The movie received mixed reviews. Roger Ebert in its review wrote that "Ron Howard is a better filmmaker than Dan Brown is a novelist; he follows Brown's formula (exotic location, startling revelation, desperate chase scene, repeat as needed) and elevates it into a superior entertainment, with Tom Hanks as a theo-intellectual Indiana Jones... it's involving, intriguing and constantly seems on the edge of startling revelations."[30]

The film received two sequels: Angels & Demons, released in 2009, and Inferno, released in 2016. Ron Howard returned to direct both sequels.

See also

[edit]- Bible conspiracy theory

- Constantinian shift – Political and theological changes

- Cultural references to Leonardo da Vinci

- Desposyni – Biblical figures described as brothers of Jesus

- False title – Grammatical construct in English

- List of best-selling books

- List of books banned in India

- Smithy code – Private amusement embedded in a court judgement in the DaVinci Code

- The Jesus Scroll – 1972 book by Donovan Joyce

- Mona Lisa replicas and reinterpretations

- The Rozabal Line – Novel by Ashwin Sanghi

- The Doomsday Conspiracy – 1991 novel by Sidney Sheldon

References

[edit]- ^ "How Good Is Dan Brown's The Lost Symbol?". Time. September 15, 2009.

- ^ Suthersanen, Uma (June 2006). "Copyright in the Courts: The Da Vinci Code". WIPO Magazine. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Wyat, Edward (November 4, 2005). "'Da Vinci Code' Losing Best-Seller Status" Archived October 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ "New novel from Dan Brown due this fall". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ Minzesheimer, Bob (December 11, 2003). "'Code' deciphers interest in religious history". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ Heller, Karen (December 29, 2016). "Meet the elite group of authors who sell 100 million books – or 350 million". Independent. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Miller, Laura (February 22, 2004). "THE LAST WORD; The Da Vinci Con". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Ford, Marcia. "Da Vinci Debunkers: Spawns of Dan Brown's Bestseller". FaithfulReader. Archived from the original on May 27, 2004. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "Affaire Pelat: Le Rapport du Juge", Le Point, no. 1112 (8–14 January 1994), p. 11.

- ^ "History vs The Da Vinci Code". Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Kelleher, Ken; Kelleher, Carolyn (April 24, 2006). "The Da Vinci Code" (FAQs). Dan Brown. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ "NBC Today Interview". NBC Today. June 3, 2003. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ "Interview With Dan Brown". CNN Sunday Morning. CNN. May 25, 2003.

- ^ "Fiction". History vs The Da Vinci Code. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ The Real Da Vinci Code. Channel 4.

- ^ Sibly, WA; Sibly, MD (1998), The History of the Albigensian Crusade: Peter of les Vaux-de-Cernay's "Historia Albigensis", Boydell, ISBN 0-85115-658-4,

Further, in their secret meetings they said that the Christ who was born in the earthly and visible Bethlehem and crucified at Jerusalem was 'evil', and that Mary Magdalene was his concubine – and that she was the woman taken in adultery who is referred to in the Scriptures; the 'good' Christ, they said, neither ate nor drank nor assumed the true flesh and was never in this world, except spiritually in the body of Paul. I have used the term 'the earthly and visible Bethlehem' because the heretics believed there is a different and invisible earth in which – according to some of them – the 'good' Christ was born and crucified.

- ^ O'Neill, Tim (2006), "55. Early Christianity and Political Power", History versus the Da Vinci Code, archived from the original on May 15, 2009, retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ^ Arendzen, John Peter (1913). "Docetae". Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton.

The idea of the unreality of Christ's human nature was held by the oldest Gnostic sects ... Docetism, as far as at present known, [was] always an accompaniment of Gnosticism or later of Manichaeism.

- ^ O'Neill, Tim (2006). "55. Nag Hammadi and the Dead Sea Scrolls". History versus the Da Vinci Code. Archived from the original on May 15, 2009. Retrieved February 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Lane, Anthony (May 29, 2006). "Heaven Can Wait" Archived October 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The New Yorker.

- ^ Miller, Laura (December 29, 2004). "The Da Vinci crock" Archived September 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Salon.com. Retrieved 2009-05-15.

- ^ Steyn, Mark (May 10, 2006) "The Da Vinci Code: bad writing for Biblical illiterates" Archived June 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Maclean's.

- ^ "The Da Vinci Code". Bookmarks Magazine. Archived from the original on September 23, 2005. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "Bookmarks Selections". Bookmarks Magazine. Archived from the original on July 8, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "The Da Vinci Code". Critics (in Greek). Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (March 17, 2003). "Spinning a Thriller From a Gallery at the Louvre" Archived April 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Lazarus, David (April 6, 2003). "'Da Vinci Code' a heart-racing thriller". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Yeoman, William (June 30, 2010), "Vampires trump wizards as readers pick their best", The West Australian, retrieved March 24, 2011List (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2011.

- ^ "Stephen King address, University of Maine". Archive. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (May 18, 2006), "Veni, Vidi, Da Vinci", RogerEbert.com

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 18, 2004), "Clueless caper just fool's gold", RogerEbert.com

- ^ Zanganeh, Lila Azam. "Umberto Eco, The Art of Fiction No. 197" Archived October 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. The Paris Review. Summer 2008, Number 185. Retrieved 2012-04-27.

- ^ "Famed author takes on Kansas". LJWorld. October 7, 2005. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ "3x12", QI (episode transcript)[permanent dead link].

- ^ "Interview with Douglas Adams Continuum". SE: Douglas Adams. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (May 18, 2006). "Movie Review: A 'Da Vinci Code' That Takes Longer to Watch Than Read". The New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ "The Dan Brown code", Language Log, University of Pennsylvania (also follow other links at the bottom of that page)

- ^ "Author Brown 'did not plagiarise'" Archived November 28, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, August 6, 2005

- ^ "Delays to latest Dan Brown novel" Archived April 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, April 21, 2006

- ^ "Judge creates own Da Vinci code". BBC News. April 27, 2006. Archived from the original on September 5, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "Authors who lost 'Da Vinci Code' copying case to mount legal appeal". Retrieved July 12, 2006.

- ^ a b "Judge rejects claims in 'Da Vinci' suit". Today.com. MSN. April 7, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2009.

- ^ Page, Jeremy. "Now Russian sues Brown over his Da Vinski Code", The Sunday Times, April 12, 2006

- ^ Grachev, Guerman (April 13, 2006), "Russian scientist to sue best-selling author Dan Brown over 'Da Vinci Code' plagiarism", Pravda, RU, archived from the original on October 7, 2012, retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ Teodorczuk, Tom (December 14, 2017). "Dan Brown faces possible new plagiarism lawsuit over 'The Da Vinci Code'". MarketWatch. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ "Novel earns vandal wrath - Code controversy deepens with warning from protesters". The Telegraph. India. May 18, 2006. Archived from the original on August 27, 2016.

- ^ "India extends Da Vinci Code ban" on the ground that it outraged the religious feeling of Christians. Roman Catholic Bishop Marampudi Joji, based in Andhra Pradesh's capital Hyderabad, welcomed the ban. BBC News, 3 June 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2006.

- ^ "HC quashes ban on Da Vinci Code | Hyderabad News - Times of India". The Times of India. TNN. June 22, 2006. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "HC allows Da Vinci Code screening in TN". www.rediff.com. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "World editions of The Da Vinci Code", Secrets (official site), Dan Brown, archived from the original on January 27, 2006.

- ^ "Harry Potter still magic for book sales", Arts, CBC, January 9, 2006, archived from the original on October 13, 2007.

- ^ "The Da Vinci Code (2006)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

Further reading

[edit]- Bock, Darrell L. Breaking the da Vinci code: Answers to the questions everyone's asking (Thomas Nelson, 2004).

- Ehrman, Bart D. Truth and fiction in The Da Vinci Code: a historian reveals what we really know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine (Oxford University Press, 2004).

- Easley, Michael J., and John Ankerberg. The Da Vinci Code Controversy: 10 Facts You Should Know (Moody Publishers, 2006).

- Gale, Cengage Learning. A Study Guide for Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code (Gale, Cengage Learning, 2015).

- Hawel, Zeineb Sami. "Did Dan Brown Break or Repair the Taboos in the Da Vinci Code? An Analytical Study of His Dialectical Style." International Journal of Linguistics and Literature (IJLL) 7.4: 5-24. online[dead link]

- Kennedy, Tammie M. "Mary Magdalene and the Politics of Public Memory: Interrogating" The Da Vinci Code"." Feminist Formations (2012): 120-139. online

- Mexal, Stephen J. "Realism, Narrative History, and the Production of the Bestseller: The Da Vinci Code and the Virtual Public Sphere." Journal of Popular Culture 44.5 (2011): 1085–1101. online[dead link]

- Newheiser, Anna-Kaisa, Miguel Farias, and Nicole Tausch. "The functional nature of conspiracy beliefs: Examining the underpinnings of belief in the Da Vinci Code conspiracy." Personality and Individual Differences 51.8 (2011): 1007–1011. online

- Olson, Carl E., and Sandra Miesel. The da Vinci hoax: Exposing the errors in The da Vinci code (Ignatius Press, 2004).

- Propp, William H. C. "Is The Da Vinci Code True?." Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 25.1 (2013): 34–48.

- Pullum, Geoffrey K. "The Dan Brown code." (2004)

- Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew. "The Dan Brown phenomenon: conspiracism in post-9/11 popular fiction." Radical History Review 2011.111 (2011): 194–201. online[dead link]

- Walsh, Richard G. "Passover Plots: From Modern Fictions to Mark and Back Again." Postscripts: The Journal of Sacred Texts, Cultural Histories, and Contemporary Contexts 3.2-3 (2007): 201–222. online

External links

[edit]- The Da Vinci Code (official website), Dan Brown, January 5, 2013

- The Da Vinci Code (official website), UK: Dan Brown, September 19, 2023

- Mysteries of Rennes-le-Château, archived from the original on April 14, 2015, retrieved January 13, 2014

- The Da Vinci Code and Textual Criticism: A Video Response to the Novel, Rochester Bible, archived from the original on December 12, 2010

- Walsh, David (May 2006), "The Da Vinci Code, novel and film, and 'countercultural' myth", WSWS (review)

- The Da Vinci Code

- 2003 American novels

- American detective novels

- Albinism in popular culture

- American mystery novels

- American thriller novels

- Bible conspiracy theories

- British Book Award–winning works

- Novels about cryptography

- Holy Grail in fiction

- Novels about museums

- Novels by Dan Brown

- Opus Dei

- Sequel novels

- Novels involved in plagiarism controversies

- Doubleday (publisher) books

- Anti-Catholic publications

- Mona Lisa

- American novels adapted into films

- Novels adapted into video games

- Censored books

- Denial of the crucifixion of Jesus

- Religious controversies in literature

- Cultural depictions of Mary Magdalene

- Novels set in one day

- Novels set in museums

- Book censorship in India

- Fiction about well-related accidents