Apollo 10

Apollo 10's Lunar Module, Snoopy, approaches the Command and Service Module Charlie Brown for redocking | |

| Mission type | Crewed lunar orbital CSM/LM flight (F) |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID |

|

| SATCAT no. |

|

| Mission duration | 8 days, 3 minutes, 23 seconds |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft |

|

| Manufacturer |

|

| Launch mass | 42,775 kg[2] |

| Landing mass | 4,945 kilograms (10,901 lb) |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 3 |

| Members | |

| Callsign |

|

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | May 18, 1969, 16:49:00 UTC[3] |

| Rocket | Saturn V SA-505 |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39B |

| End of mission | |

| Recovered by | USS Princeton |

| Landing date | May 26, 1969, 16:52:23 UTC |

| Landing site | 15°2′S 164°39′W / 15.033°S 164.650°W |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Selenocentric |

| Periselene altitude | 109.6 kilometers (59.2 nmi) |

| Aposelene altitude | 113.0 kilometers (61.0 nmi) |

| Inclination | 1.2 degrees |

| Period | 2 hours |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Command and service module |

| Orbital insertion | May 21, 1969, 20:44:54 UTC |

| Orbital departure | May 24, 1969, 10:25:38 UTC |

| Orbits | 31 |

| Lunar orbiter | |

| Spacecraft component | Lunar Module |

| Orbits | 4 (while solo) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Periselene altitude | 14.4 kilometers (7.8 nmi) |

| Docking with LM | |

| Docking date | May 18, 1969, 20:06:36 UTC |

| Undocking date | May 22, 1969, 19:00:57 UTC |

| Docking with LM Ascent Stage | |

| Docking date | May 23, 1969, 03:11:02 UTC |

| Undocking date | May 23, 1969, 05:13:36 UTC |

Left to right: Cernan, Stafford, Young | |

Apollo 10 (May 18–26, 1969) was the fourth human spaceflight in the United States' Apollo program and the second to orbit the Moon. NASA, the mission's operator, described it as a "dress rehearsal" for the first Moon landing (Apollo 11, two months later[4]). It was designated an "F" mission, intended to test all spacecraft components and procedures short of actual descent and landing.

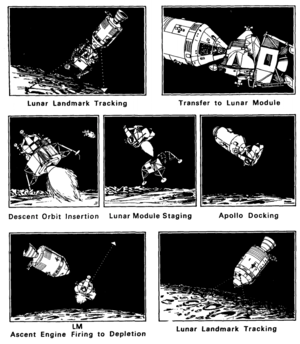

After the spacecraft reached lunar orbit, astronaut John Young remained in the Command and Service Module (CSM) while astronauts Thomas Stafford and Gene Cernan flew the Apollo Lunar Module (LM) to within 14.4 kilometers (7.8 nmi) of the lunar surface, the point at which powered descent for landing would begin on a landing mission. After four orbits they rejoined Young in the CSM and, after the CSM completed its 31st orbit of the Moon, they returned safely to Earth.

While NASA had considered attempting the first crewed lunar landing on Apollo 10, mission planners ultimately decided that it would be prudent to have a practice flight to hone the procedures and techniques. The crew encountered some problems during the flight: pogo oscillations during the launch phase and a brief, uncontrolled tumble of the LM ascent stage in lunar orbit during its solo flight. However, the mission accomplished its major objectives. Stafford and Cernan observed and photographed Apollo 11's planned landing site in the Sea of Tranquility. Apollo 10 spent 61 hours and 37 minutes orbiting the Moon, for about eight hours of which Stafford and Cernan flew the LM apart from Young in the CSM, and about eight days total in space. Additionally, Apollo 10 set the record for the highest speed attained by a crewed vehicle: 39,897 km/h (11.08 km/s or 24,791 mph) on May 26, 1969, during the return from the Moon.

The mission's call signs were the names of the Peanuts characters Charlie Brown for the CSM and Snoopy for the LM, who became Apollo 10's semi-official mascots.[5] Peanuts creator Charles Schulz also drew mission-related artwork for NASA.[6]

Framework

[edit]Background

[edit]By 1967, NASA had devised a list of mission types, designated by letters, that needed to be flown before a landing attempt, which would be the "G" mission. The early uncrewed flights were considered "A" or "B" missions, while Apollo 7, the crewed-flight test of the Command and Service Module (CSM), was the "C" mission. The first crewed orbital test of the Lunar Module (LM) was accomplished on Apollo 9, the "D" mission. Apollo 8, flown to the Moon's orbit without an LM, was considered a "C-prime" mission, but its success gave NASA the confidence to skip the "E" mission, which would have tested the full Apollo spacecraft in medium or high Earth orbit. Apollo 10, the dress rehearsal for the lunar landing, was to be the "F" mission.[7][8]

NASA considered skipping the "F" mission as well and attempting the first lunar landing on Apollo 10. Some with the agency advocated this, feeling it senseless to bring astronauts so close to the lunar surface, only to turn away. Although the lunar module intended for Apollo 10 was too heavy to perform the lunar mission, the one intended for Apollo 11 could be substituted by delaying Apollo 10 a month from its May 1969 planned launch.[9] NASA official George Mueller favored a landing attempt on Apollo 10; he was known for his aggressive approach to moving the Apollo program forward.[10] However, Director of Flight Operations Christopher C. Kraft and others opposed this, feeling that new procedures would have to be developed for a rendezvous in lunar orbit and that NASA had incomplete information regarding the Moon's mass concentrations, which might throw off the spacecraft's trajectory. Lieutenant General Sam Phillips, the Apollo Program Manager, listened to the arguments on both sides and decided that having a dress rehearsal was crucial.[9]

Crew and key Mission Control personnel

[edit]| Position | Astronaut | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander (CDR) | Thomas P. Stafford Third spaceflight | |

| Command Module Pilot (CMP) | John W. Young Third spaceflight | |

| Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) | Eugene A. Cernan Second spaceflight | |

On November 13, 1968, NASA announced the crew members of Apollo 10.[7] Thomas P. Stafford, the commander, was 38 years old at the time of the mission. A 1952 graduate of the Naval Academy, he was commissioned in the Air Force. Selected for the second group of astronauts in 1962, he flew as pilot of Gemini 6A (1965) and command pilot of Gemini 9A (1966).[11] John Young, the command module pilot, was 38 years old and a commander in the Navy at the time of Apollo 10. A 1952 graduate of Georgia Tech who entered the Navy after graduation and became a test pilot in 1959, he was selected as a Group 2 astronaut alongside Stafford. He flew in Gemini 3 with Gus Grissom in 1965, becoming the first American not of the Mercury Seven to fly in space. Young thereafter commanded Gemini 10 (1966), flying with Michael Collins.[12][13] Eugene Cernan, the lunar module pilot, was a 35-year-old commander in the Navy at the time of Apollo 10. A 1952 graduate of Purdue University, he entered the Navy after graduation. Selected for the third group of astronauts in 1963, Cernan flew with Stafford on Gemini 9A before his assignment to Apollo 10.[14] With five prior flights among them, the Apollo 10 crew was the most experienced to reach space until the Space Shuttle era,[15] and the first American space mission whose crew were all spaceflight veterans.[16]

The backup crew for Apollo 10 was L. Gordon Cooper Jr as commander, Donn F. Eisele as command module pilot, and Edgar D. Mitchell as lunar module pilot. By the normal crew rotation in place during Apollo, Cooper, Eisele, and Mitchell would have flown on Apollo 13,[a] but Cooper and Eisele never flew again. Deke Slayton, Director of Flight Crew Operations, felt that Cooper did not train as hard as he could have. Eisele was blackballed because of incidents during Apollo 7, which he had flown as CMP and which had seen conflict between the crew and ground controllers; he had also been involved in a messy divorce. Slayton only assigned the two as backups because he had few veteran astronauts available.[18] Cooper and Eisele were replaced by Alan Shepard and Stuart Roosa respectively. Feeling they needed additional training time, George Mueller rejected the Apollo 13 crew. The crew was switched to Apollo 14, which saw Shepard and Mitchell walk on the Moon.[18]

For projects Mercury and Gemini, a prime and a backup crew had been designated, but for Apollo, a third group of astronauts, known as the support crew, was also designated. Slayton created the support crews early in the Apollo program on the advice of McDivitt, who would lead Apollo 9. McDivitt believed that, with preparation going on in facilities across the U.S., meetings that needed a member of the flight crew would be missed. Support crew members were to assist as directed by the mission commander.[19] Usually low in seniority, they assembled the mission's rules, flight plan, and checklists, and kept them updated.[20][21] For Apollo 10, they were Joe Engle, James Irwin, and Charles Duke.[22]

Flight directors were Gerry Griffin, Glynn Lunney, Milt Windler, and Pete Frank.[23] Flight directors during Apollo had a one-sentence job description: "The flight director may take any actions necessary for crew safety and mission success."[24] CAPCOMs were Duke, Engle, Jack Lousma, and Bruce McCandless II.[22]

Call signs and mission insignia

[edit]

The command module was given the call sign "Charlie Brown" and the lunar module the call sign "Snoopy". These were taken from the characters in the comic strip, Peanuts, Charlie Brown and Snoopy.[22] These names were chosen by the astronauts with the approval of Charles Schulz, the strip's creator,[25] who was uncertain it was a good idea, since Charlie Brown was always a failure.[26] The choice of names was deemed undignified by some at NASA, as were the choices for Apollo 9's CM and LM ("Gumdrop" and "Spider"). Public relations chief Julian Scheer urged a change for the lunar landing mission.[27] But for Apollo 10, according to Cernan, "The P.R.-types lost this one big-time, for everybody on the planet knew the klutzy kid and his adventuresome beagle, and the names were embraced in a public relations bonanza."[28] Apollo 11's call signs were "Columbia" for the command module and "Eagle" for the lunar module.[29]

Snoopy, Charlie Brown's dog, was chosen for the call sign of the lunar module since it was to "snoop" around the landing site, with Charlie Brown given to the command module as Snoopy's companion.[30] Snoopy had been associated for some time with the space program, with workers who performed in an outstanding manner awarded silver "Snoopy pins", and Snoopy posters were seen at NASA facilities, with the cartoon dog having traded in his World War I aviator's headgear for a space helmet.[25] Stafford stated that, given the pins, "the choice of Snoopy [as call sign] was a way of acknowledging the contributions of the hundreds of thousands of people who got us there".[31] The use of the dog was also appropriate since, in the comic strip, Snoopy had journeyed to the Moon the year before, thus defeating, according to Schulz, "the Americans, the Russians, and that stupid cat next door".[25]

The shield-shaped mission insignia shows a large, three-dimensional Roman numeral X sitting on the Moon's surface, in Stafford's words, "to show that we had left our mark". Although it did not land on the Moon, the prominence of the number represents the contributions the mission made to the Apollo program. A CSM circles the Moon as an LM ascent stage flies up from its low pass over the lunar surface with its engine firing. The Earth is visible in the background. On the mission patch, a wide, light blue border carries the word APOLLO at the top and the crew names around the bottom. The patch is trimmed in gold. The insignia was designed by Allen Stevens of Rockwell International.[32]

Training and preparation

[edit]

Apollo 10, the "F" mission or dress rehearsal for the lunar landing, had as its primary objectives to demonstrate crew, space vehicle and mission support facilities performance during a crewed mission to lunar orbit, and to evaluate the performance of the lunar module there. In addition, it was to attempt photography of Apollo Landing Site 2 (ALS-2) in the Sea of Tranquillity, the contemplated landing site for Apollo 11.[33] According to Stafford,

Our flight was to take the first lunar module to the moon. We would take the lunar module, go down to within about ten miles above the moon, nine miles above the mountains, radar map, photo map, pick out the first landing site, do the first rendezvous around the moon, pick out some future landing sites, and come home.[34]

Apollo 10 was to adhere as closely as possible to the plans for Apollo 11, including its trajectory to and from lunar orbit, the timeline of mission events, and even the angle of the Sun at ALS-2. However, no landing was to be attempted.[35] ALS-1, given that number because it was the furthest to the east of the candidate sites,[b] and also located in the Sea of Tranquility, had been extensively photographed by Apollo 8 astronauts; at the suggestion of scientist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt, the launch of Apollo 10 had been postponed a day so ALS-2 could be photographed under proper conditions. ALS-2 was chosen as the lunar landing site since it was relatively smooth, of scientific interest, and ALS-1 was deemed too far to the east.[36] Thus, when Apollo 10's launch date was announced on January 10, 1969, it was shifted from its placeholder date of May 1 to May 17, rather than to May 16. On March 17, 1969, the launch was slipped one day to May 18, to allow for a better view of ALS-3, to the west of ALS-2.[7] Another deviation from the plans for Apollo 11 was that Apollo 10 was to spend an additional day in lunar orbit once the CSM and LM rendezvoused; this was to allow time for additional testing of the LM's systems, as well as for photography of possible future Apollo landing sites.[37]

The Apollo 10 astronauts undertook five hours of formal training for each hour of the mission's eight-day duration. This was in addition to the normal mission preparations such as technical briefings, pilot meetings and study. They took part in the testing of the CSM at the Downey, California, facility of its manufacturer, North American Rockwell, and of the LM at Grumman in Bethpage, New York. They visited Cambridge, Massachusetts, for briefings on the Apollo Guidance Computer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Instrumentation Laboratory. They each spent more than 300 hours in simulators of the CM or LM at the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston and at Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. To train for the high-acceleration conditions they would experience in returning to Earth's atmosphere, they endured MSC's centrifuge.[38]

Lunar landing capability

[edit]| Component | Apollo 10 LM-4 | Apollo 11 LM-5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lb | kg | lb | kg | |

| Descent stage dry[39] | 4,703 | 2,133 | 4,483 | 2,033 |

| Descent stage propellant[40] | 18,219 | 8,264 | 18,184 | 8,248 |

| Descent stage subtotal | 22,922 | 10,397 | 22,667 | 10,282 |

| Ascent stage dry[39] | 4,781 | 2,169 | 4,804 | 2,179 |

| Ascent stage propellant[41] | 2,631 | 1,193 | 5,238 | 2,376 |

| Ascent stage subtotal | 7,412 | 3,362 | 10,042 | 4,555 |

| Equipment | 401 | 182 | 569 | 258 |

| Total[39] | 30,735 | 13,941 | 33,278 | 15,095 |

While Apollo 10 was meant to follow the procedures of a lunar landing mission to the point of powered descent, Apollo 10's LM was not capable of landing and returning to lunar orbit. The ascent stage was loaded with the amount of fuel and oxidizer it would have had remaining if it had lifted off from the surface and reached the altitude at which the Apollo 10 ascent stage fired; this was only about half the total amount required for lift off and rendezvous with the CSM. The mission-loaded LM weighed 13,941 kilograms (30,735 lb), compared to 15,095 kilograms (33,278 lb) for the Apollo 11 LM which made the first landing.[39] Additionally, the software necessary to guide the LM to a landing was not available at the time of Apollo 10.[10]

Craig Nelson wrote in his book Rocket Men that NASA took special precaution to ensure Stafford and Cernan would not attempt to make the first landing. Nelson quoted Cernan as saying "A lot of people thought about the kind of people we were: 'Don't give those guys an opportunity to land, 'cause they might!' So the ascent module, the part we lifted off the lunar surface with, was short-fueled. The fuel tanks weren't full. So had we literally tried to land on the Moon, we couldn't have gotten off."[42] Mueller, NASA's Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, stated,

There had been some speculation about whether or not the crew might have landed, having gotten so close. They might have wanted to, but it was impossible for that lunar module to land. It was an early design that was too heavy for a lunar landing, or, to be more precise, too heavy to be able to complete the ascent back to the command module. It was a test module, for the dress rehearsal only, and that was the way it was used.[43]

Equipment

[edit]The descent stage of the LM was delivered to KSC on October 11, 1968, and the ascent stage arrived five days later. They were mated on November 2. The Service Module (SM) and Command Module (CM) arrived on November 24 and were mated two days later. Portions of the Saturn V launch vehicle arrived during November and December 1968, and the complete launch vehicle was erected in the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) on December 30. After being tested in an altitude chamber, the CSM was placed atop the launch vehicle on February 6, 1969.[44] The completed space vehicle was rolled out to Launch Complex 39B on March 11, 1969—the fact that it had been assembled in the VAB's High Bay 2 (the first time it had been used) required the crawler to exit the rear of the VAB before looping around the building and joining the main crawlerway, proceeding to the launch pad.[45] This rollout, using Mobile Launch Platform-3 (MLP-3),[7] happened eight days after the launch of Apollo 9, while that mission was still in orbit.[45]

The launch vehicle for Apollo 10 was a Saturn V, designated AS-505,[46] the fifth flight-ready Saturn V to be launched and the third to take astronauts to orbit.[47] The Saturn V differed from that used on Apollo 9 in having a lower dry weight (without propellant) in its first two stages, with a significant reduction to the interstage joining them. Although the S-IVB third stage was slightly heavier, all three stages could carry a greater weight of propellant, and the S-II second stage generated more thrust than that of Apollo 9.[48]

The Apollo spacecraft for the Apollo 10 mission was composed of Command Module 106 (CM-106), Service Module 106 (SM-106, together with the CM known as CSM-106), Lunar Module 4 (LM-4), a spacecraft-lunar module adapter (SLA), numbered as SLA-13A, and a launch escape system.[49][50] The SLA was a mating structure joining the Instrument Unit on the S-IVB stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle and the CSM, and acted as a housing for the LM, while the Launch Escape System (LES) contained rockets to propel the CM to safety if there was an aborted launch.[49] At about 76.99 metric tons, Apollo 10 would be the heaviest spacecraft to reach orbit to that point.[7]

Mission highlights

[edit]

Launch and outbound trip

[edit]Apollo 10 launched from KSC on May 18, 1969, at 12:49:00 EDT (16:49:00 UT), at the start of a 4.5-hour launch window. The launch window was timed to secure optimal lighting conditions at Apollo Landing Site 2 at the time of the LM's closest approach to the site days later. The launch followed a countdown that had begun at 21:00:00 EDT on May 16 (01:00:00 UT on May 17). Because preparations for Apollo 11 had already begun at Pad 39A, Apollo 10 launched from Pad 39B, becoming the only Apollo flight to launch from that pad[51] and the only one to be controlled from its Firing Room 3.[10][52]

Problems that arose during the countdown were dealt with during the built-in holds, and did not delay the mission.[22] On the day before launch, Cernan had been stopped for speeding while returning from a final visit with his wife and child. Lacking identification and under orders to tell no one who he was, Cernan later attested in his autobiography that he had feared being arrested. Launch pad leader Gunther Wendt, who had pulled over nearby after recognizing Cernan, explained the situation to the police officer, who then released Cernan despite the officer's skepticism that Cernan was an astronaut.[53]

The crew experienced a somewhat rough ride on the way to orbit due to pogo oscillations.[54] About 12 minutes after liftoff, the spacecraft entered a low Earth orbit with a high point of 185.79 kilometers (100.32 nautical miles) and a low point of 184.66 kilometers (99.71 nautical miles).[55] All appeared to be normal during the systems review period in Earth orbit, and the crew restarted the S-IVB third stage to achieve trans-lunar injection (TLI) and send them towards the Moon. The vehicle shook again while executing the TLI burn, causing Cernan to be concerned that they might have to abort. However, the TLI burn was completed without incident.[56] Young then performed the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver, separating the CSM from the S-IVB stage, turning around, and docking its nose to the top of the lunar module (LM), before separating from the S-IVB. Apollo 10 was the first mission to carry a color television camera inside the spacecraft, and mission controllers in Houston watched as Young performed the maneuver. Soon thereafter, the large television audience was treated to color views of the Earth.[57] One problem that was encountered was that the mylar cover of the CM's hatch had pulled loose, spilling quantities of fiberglass insulation into the tunnel, and then into both the CM and LM.[58] The S-IVB was fired by ground command and sent into solar orbit with a period of 344.88 days.[59]

The crew settled in for the voyage to the Moon. They had a light workload, and spent much of their time studying the flight plan or sleeping. They made five more television broadcasts back to Earth, and were informed that more than a billion people had watched some part of their activities.[60] In June 1969, the crew would accept a special Emmy Award on behalf of the first four Apollo crews for their television broadcasts from space.[61] One slight course correction was necessary;[60] this occurred at 26:32:56.8 into the mission and lasted 7.1 seconds. This aligned Apollo 10 with the trajectory Apollo 11 was expected to take.[59] One issue the crew encountered was bad-tasting food, as Stafford apparently used a double dose of chlorine in their drinking water, which had to be placed in their dehydrated food to reconstitute it.[7]

Lunar orbit

[edit]

Arrival and initial operations

[edit]At 75:55:54 into the mission, 176.1 kilometers (95.1 nautical miles) above the far side of the Moon, the CSM's service propulsion system (SPS) engine was fired for 356.1 seconds to slow the spacecraft into a lunar orbit of 314.8 by 111.5 kilometers (170.0 by 60.2 nautical miles). This was followed, after two orbits of the Moon, with a 13.9-second firing of the SPS to circularize the orbit to 113.0 by 109.6 kilometers (61.0 by 59.2 nautical miles) at 80:25:08.1.[59] Within the first couple of hours after the initial lunar orbit insertion burn and following the circularization burn, the crew turned to tracking planned landmarks on the surface below to record observations and take photographs. In addition to ALS-1, ALS-2, and ALS-3, the crew of Apollo 10 observed and photographed features on the near and far sides of the Moon, including the craters Coriolis, King, and Papaleksi.[62] Shortly after the circularization burn, the crew partook in a scheduled half-hour color-television broadcast with descriptions and video transmissions of views of the lunar surface below.[63]

About an hour after the second burn, the LM crew of Stafford and Cernan entered the LM to check out its systems.[59] They were met with a blizzard of fiberglass particles from the earlier problem, which they cleaned up with a vacuum cleaner as best they could. Stafford had to help Cernan remove smaller bits from his hair and eyebrows.[64] Stafford later commented that Cernan looked like he just came out of a chicken coop, and that the particles made them itch and got into the air conditioning system, and they were scraping it off the filter screens for the rest of the mission.[10] This was merely an annoyance, but the particles may have gotten into the docking ring joining the two craft and caused it to misalign slightly. Mission Control determined that this was still within safe limits.[65]

The flight of Snoopy

[edit]

After Stafford and Cernan checked out Snoopy, they returned to Charlie Brown for a rest. Then they re-entered Snoopy and undocked it from the CSM at 98:29:20.[63] Young, who remained in the CSM, became the first person to fly solo in lunar orbit.[66] After undocking, Stafford and Cernan deployed the LM's landing gear and inspected the LM's systems. The CSM performed an 8.3-second burn with its RCS thrusters to separate itself from the LM by about 30 feet, after which Young visually inspected the LM from the CSM. The CSM performed another separation burn, this time separating the two spacecraft by about 3.7 kilometers (2 nautical miles).[63] The LM crew then performed the descent orbit insertion maneuver by firing their descent engine for 27.4 seconds at 99:46:01.6, and tested their craft's landing radar as they approached the 15,000-meter (50,000-foot) altitude where the subsequent Apollo 11 mission would begin powered descent to land on the Moon.[67] Previously, the LM's landing radar had only been tested under terrestrial conditions.[68] While the LM executed these maneuvers, Young monitored the location and status of the LM from the CSM, standing by to rescue the LM crew if necessary.[69] Cernan and Stafford surveyed ALS-2, coming within 15.6 kilometers (8.4 nautical miles) of the surface at a point 15 degrees to its east, then performed a phasing burn at 100:58:25.93, thrusting for just under 40 seconds to allow a second pass at ALS-2, when the craft came within 14.4 kilometers (7.8 nautical miles) of the Moon, its closest approach.[67] Reporting on his observations of the site from the LM's low passes, Stafford indicated that ALS-2 seemed smoother than he had expected[69] and described its appearance as similar to the desert surrounding Blythe, California;[70] but he observed that Apollo 11 could face rougher terrain downrange if it approached off-target.[69] Based upon Apollo 10's observations from relatively low altitude, NASA mission planners became comfortable enough with ALS-2 to confirm it as the target site for Apollo 11.[71]

The next action was to prepare to separate the LM ascent stage from the descent stage, to jettison the descent stage, and fire the Ascent Propulsion System to return the ascent stage towards the CSM. As Stafford and Cernan prepared to do so, the LM began to gyrate out of control.[72] Alarmed, Cernan exclaimed, "Son of a bitch!" into a hot mic being broadcast live, which, combined with other language used by the crew during the mission, generated some complaints back on Earth.[73] Stafford discarded the descent stage about five seconds after the tumbling began[63] and fought to regain control manually, suspecting that there might have been an "open thruster", or a thruster stuck firing.[74] He did so in time to orient the spacecraft to rejoin Charlie Brown.[72] The problem was traced to a switch controlling the mode of the abort guidance system; it was to be moved as part of the procedure, but both of the crew members switched it, thus returning it to the original position. Had they fired Snoopy in the wrong direction, they might have missed the rendezvous with Charlie Brown or crashed into the Moon.[75] Once Stafford had regained control of the LM ascent stage, which took about eight seconds,[72] the pair fired the ascent engine at the lowest point of the LM's orbit, mimicking the orbital insertion maneuver after launch from the lunar surface in a later landing mission. Snoopy coasted on that trajectory for about an hour before firing the engine once more to further fine-tune its approach to Charlie Brown.[63]

Snoopy rendezvoused with and re-docked with Charlie Brown at 106:22:02, just under eight hours after undocking.[63] The docking was telecast live in color from the CSM.[76][77] Once Cernan and Stafford had re-entered Charlie Brown, Snoopy was sealed off and separated from Charlie Brown. The rest of the LM's ascent-stage engine fuel was burned to send it on a trajectory past the Moon and into a heliocentric orbit.[78][79]

It was the only Apollo LM to meet this fate. The Apollo 11 ascent stage would be left in lunar orbit to crash randomly, while ascent stages of later Apollo mission (12, 14, 15 and 17) were steered into the Moon to obtain readings from seismometers placed nearby on the surface, with two exceptions: Apollo 13's ascent stage, which the crew used as a "life boat" to get safely back to Earth before releasing it to burn up in Earth's atmosphere, and Apollo 16's, which NASA lost control of after jettison.[79]

Return to Earth

[edit]

After ejecting the LM ascent stage, the crew slept and performed photography and observation of the lunar surface from orbit. Though the crew located 18 landmarks on the surface and took photographs of various surface features, crew fatigue necessitated the cancellation of two scheduled television broadcasts. Thereafter, the main Service Propulsion System engine of the CSM re-ignited for about 2.5 minutes to set Apollo 10 on a trajectory towards Earth, achieving such a trajectory at 137:39:13.7. As it departed lunar orbit, Apollo 10 had orbited the Moon 31 times over the span of about 61 hours and 37 minutes.[63]

During their journey back to Earth, the crew performed some observational activities which included star-Earth horizon sightings for navigation. The crew also performed a scheduled test to gauge the reflectivity of the CSM's high-gain antenna and broadcast six television transmissions of varying durations to show views inside the spacecraft and of the Earth and Moon from the crew's vantage point.[63] Cernan reported later that he and his crewmates became the first to "successfully shave in space" during the return trip, using a safety razor and thick shaving gel, as such items had been deemed a safety hazard and prohibited on earlier flights.[80] The crew fired the engine of the CSM for the only mid-course-correction burn required during the return trip at 188:49:58, a few hours before separation of the CM from the SM. The burn lasted about 6.7 seconds.[63]

As the spacecraft rapidly approached Earth on the final day of the mission, the Apollo 10 crew traveled faster than any humans before or since, relative to Earth: 39,897 km/h (11.08 km/s or 24,791 mph).[81][82] This is because the return trajectory was designed to take only 42 hours rather than the normal 56.[83] The Apollo 10 crew also traveled farther than any humans before or since from their (Houston) homes: 408,950 kilometers (220,820 nmi) (though the Apollo 13 crew was 200 km farther away from Earth as a whole).[84]

At 191:33:26, the CM (which contained the crew) separated from the SM in preparation for reentry, which occurred about 15 minutes later at 191:48:54.5.[63] Splashdown of the CM occurred about 15 minutes after reentry in the Pacific Ocean about 740 kilometres (400 nmi) east of American Samoa on May 26, 1969, at 16:52:23 UTC and mission elapsed time 192:03:23.[63] The astronauts were recovered by USS Princeton. They spent about four hours aboard, during which they took a congratulatory phone call from President Richard Nixon.[85] As they had not made contact with the lunar surface, Apollo 10's crew were not required to quarantine like the first landing crews would be.[86] They were flown to Pago Pago International Airport in Tafuna for a greeting reception, before boarding a C-141 cargo plane to Ellington Air Force Base near Houston.[85]

Aftermath

[edit]Orbital operations and the solo maneuvering of the LM in partial descent to the lunar surface paved the way for the successful Apollo 11 lunar landing by demonstrating the capabilities of the mission hardware and systems. The crew demonstrated that the checkout procedures of the LM and initial descent and rendezvous could be accomplished within the allotted time, that the communication systems of the LM were sufficient, that the rendezvous and landing radars of the LM were operational in lunar orbit, and that the two spacecraft could be adequately monitored by personnel on Earth. Additionally, the precision of lunar orbital navigation improved with Apollo 10 and, combined with data from Apollo 8, NASA expected that it had achieved a level of precision sufficient to execute the first crewed lunar landing.[63] After about two weeks of Apollo 10 data analysis, a NASA flight readiness team cleared Apollo 11 to proceed with its scheduled July 1969 flight.[87] On July 16, 1969, the next Saturn V to launch carried the astronauts of Apollo 11: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins. On July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin landed on the Moon, and four days later the three astronauts returned to Earth, fulfilling John F. Kennedy's challenge to Americans to land astronauts on the Moon and return them safely to Earth by the end of the 1960s.[88][89]

In July 1969, Stafford replaced Alan Shepard as Chief Astronaut, and then became deputy director of Flight Crew Operations under Deke Slayton.[7] In his memoirs, Stafford wrote that he could have put his name back in the flight rotation, but wanted managerial experience.[90] In 1972, Stafford was promoted to brigadier general and assigned to command the American portion of the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project, which flew in July 1975. He commanded the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base in California, and retired in November 1979 as a lieutenant general. Young commanded the Apollo 16 lunar landing mission flown in April 1972. From 1974 to 1987, Young served as Chief Astronaut, commanding the STS-1 (1981) and STS-9 (1983) Space Shuttle missions in April 1981 and November 1983, respectively, and retired from NASA's Astronaut Corps in 2004. Gene Cernan commanded the final Apollo lunar mission, Apollo 17, flown in December 1972. Cernan retired from NASA and the Navy as a captain in 1976.[7][66][91]

Hardware disposition

[edit]

The Smithsonian has been accountable for the command module Charlie Brown since 1970. The spacecraft was on display in several countries until it was placed on loan to the London Science Museum in 1978.[92] Charlie Brown's SM was jettisoned just before re-entry and burned up in the Earth's atmosphere, its remnants scattering in the Pacific Ocean.[63]

After translunar injection, the Saturn V's S-IVB third stage was accelerated past Earth escape velocity to become space debris; as of 2020[update], it remains in a heliocentric orbit.[93]

The ascent stage of the Lunar Module Snoopy was jettisoned into a heliocentric orbit. Snoopy's ascent stage orbit was not tracked after 1969, and its whereabouts were unknown. In 2011, a group of amateur astronomers in the UK started a project to search for it. In June 2019, the Royal Astronomical Society announced a possible rediscovery of Snoopy, determining that small Earth-crossing asteroid 2018 AV2 is likely to be the spacecraft with "98%" certainty.[94] It is the only once-crewed spacecraft known to still be in outer space without a crew.[95][96]

Snoopy's descent stage was jettisoned in lunar orbit; its current location is unknown, though it may have eventually crashed into the Moon as a result of orbital decay.[97] Phil Stooke, a planetary scientist who studied the lunar crash sites of the LM's ascent stages, wrote that the descent stage "crashed at an unknown location",[98] and another source stated that the descent stage "eventually impact(ed) within a few degrees of the equator on the near side".[99] Richard Orloff and David M. Harland, in their sourcebook on Apollo, stated that "the descent stage was left in the low orbit, but perturbations by 'mascons' would have caused this to decay, sending the stage to crash onto the lunar surface".[100]

Images

[edit]-

The S-IC first stage in the VAB

-

Apollo 10 during rollout

-

The crew poses with their launch vehicle; left to right, Cernan, Young, Stafford.

-

Crew boarding the command module before launch

-

Apollo 10 view of Earthrise

-

CSM Charlie Brown

-

Apollo Lunar Module Snoopy about to dock with the command module

-

Necho crater on the far side of the Moon

-

High-albedo swirls within unnamed crater east of Firsov

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The role of the backup crew was to train and be prepared to fly in the event something happened to the prime crew.[17] Backup crews, according to the rotation, were assigned as the prime crew three missions after their assignment of backups.

- ^ The five candidate sites for the first lunar landing, ALS-1 through ALS-5, were numbered from the easternmost to the westernmost. See Press Kit, p. 37

References

[edit]- ^ "Apollo 10 summary". NASA. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ "Apollo 10". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive (NSSDCA). Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ Apollo 10, NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive (NSSDCA), retrieved November 29, 2022

- ^ Press Kit, p. 1.

- ^ "Replicas of Snoopy and Charlie Brown decorate top of console in MCC". NASA. May 28, 1969. NASA Photo ID: S69-34314. Archived from the original on June 19, 2001. Retrieved June 25, 2013. Photo description available here Archived October 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ McKinnon, Mika (April 30, 2014). "Snoopy the Astrobeagle, NASA's Mascot for Safety". Gizmodo. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h LaPage, Andrew (May 29, 2019). "Apollo 10: The Adventure of Charlie Brown and Snoopy". Drew ex Machina (Blog). Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 234–235.

- ^ a b Chaikin, pp. 151–152.

- ^ a b c d Lindsay, Hamish. "Apollo 10". Colin Hackellar. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Thomas P. Stafford, Lieutenant General, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) NASA astronaut (former)" (PDF). Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. March 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Orloff & Harland, p. 471.

- ^ Press Kit, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Press Kit, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Stafford & Cassutt, p. 545.

- ^ Orloff & Harland, p. 279.

- ^ "50 years ago, NASA names Apollo 11 crew". NASA. January 30, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Slayton & Cassutt, p. 236.

- ^ Slayton & Cassutt, p. 184.

- ^ Hersch, Matthew (July 19, 2009). "The fourth crewmember". Air & Space/Smithsonian. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ Brooks, p. 261.

- ^ a b c d Orloff & Harland, p. 256.

- ^ Orloff & Harland, p. 236.

- ^ Williams, Mike (September 13, 2012). "A legendary tale, well-told". Rice University Office of Public Affairs. Archived from the original on August 17, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c Roberts, Steven V. (May 26, 1969). "You're a brave man, Charlie Brown". The New York Times. p. 20.

- ^ French & Burgess, p. 1348.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Cernan, p. 1156.

- ^ Orloff & Harland, p. 280.

- ^ Alaina (May 16, 2019). "Snoopy, Charlie Brown and Apollo 10". Kennedy Space Center. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Stafford & Cassutt, p. 547.

- ^ Hengeveld, Ed (May 20, 2008). "The man behind the Moon mission patches". collectSPACE. Retrieved July 18, 2009. "A version of this article was published concurrently in the British Interplanetary Society's Spaceflight magazine." (June 2008; pp. 220–225).

- ^ Orloff & Harland, pp. 256, 285.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 1337–1338.

- ^ Press Kit, p. 2.

- ^ Wilhelms, pp. 189–192.

- ^ Press Kit, pp. 6, 8.

- ^ Press Kit, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Orloff 2004, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Orloff 2004, p. 295.

- ^ Orloff 2004, p. 296.

- ^ Nelson 2009, p. 14

- ^ "Apollo 10". NASA Science. April 9, 2019. Archived from the original on August 4, 2022. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ Orloff & Harland, p. 257.

- ^ a b "50 years ago: Apollo 10 rolls out to launch pad". NASA. March 11, 2019. Retrieved June 19, 2022.

- ^ "Apollo 10: Background". Apollo 10 Lunar Flight Journal. NASA. February 10, 2017. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Mission Report, p. 14-1.

- ^ Press Kit, p. 55.

- ^ a b Press Kit, p. 38.

- ^ "Apollo/Skylab ASTP and Shuttle Orbiter Major End Items" (PDF). NASA. March 1978. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ "Day 1, part 1: Countdown, launch and climb to orbit". Apollo 10 Lunar Flight Journal. NASA. February 6, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ Neufeld, Michael (May 22, 2020). "Launch Complex 39: From Saturn to Shuttle to SpaceX and SLS". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Cernan, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Cernan, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Orloff 2004, p. 286.

- ^ Cernan, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Brooks, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Mission Report, pp. 9–4, 9–8.

- ^ a b c d Orloff & Harland, p. 260.

- ^ a b Brooks, pp. 304–306.

- ^ Gent, George (June 9, 1969). "N.B.C.'s 'Teacher, Teacher' Voted Best TV Drama". The New York Times. p. 94.

- ^ "Apollo 10 Day 4, part 13: Acclimatising in lunar orbit". Apollo 10 Lunar Flight Journal. NASA. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Orloff 2004, pp. 72–79.

- ^ Chaikin, p. 156.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 1374–1376.

- ^ a b Neal, Valerie (January 19, 2018). "John W. Young, an Astronaut's Astronaut (1930-2018)". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Orloff & Harland, pp. 259–260.

- ^ Press Kit, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Chaikin, p. 158.

- ^ Wilhelms, p. 191.

- ^ Wilhelms, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Chaikin, p. 159.

- ^ Simmons, Roger (May 28, 2019). "Foul-mouthed Apollo astronauts got space program in trouble 50 years ago". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Cernan, p. 218.

- ^ French & Burgess, pp. 1385–1391.

- ^ Gohd, Chelsea (May 18, 2019). "Snoopy to the Moon! Apollo 10 Commander Looks Back on Historic Flight 50 Years Ago". Space.com. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "John Young: Not just the commander of Apollo 16". Universe Magazine. April 15, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Ryba, Jeanne, ed. (July 8, 2009). "Apollo 10". NASA. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ a b "Current locations of the Apollo Command Module Capsules (and Lunar Module crash sites)". Apollo: Where are they now?. NASA. Retrieved December 27, 2014.

- ^ Cernan, p. 220.

- ^ Wall, Mike (April 23, 2019). "The Most Extreme Human Spaceflight Records". Space.com. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Granath, Bob (February 24, 2015). "Apollo 10 Anniversary Catapults Next Step". NASA. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- ^ Stafford & Cassutt, p. 458.

- ^ Holtkamp, Gerhard (June 6, 2009). "Far Away From Home". SpaceTimeDreamer (Blog). SciLogs. Archived from the original on October 31, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "50 Years Ago: Apollo 10 Clears the Way for the first Moon Landing". NASA. May 23, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Cernan, p. 222.

- ^ Dorminey, Bruce (May 19, 2019). "Apollo 10 Gave NASA The Chutzpah To Meet JFK's Lunar Challenge". Forbes. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Overview". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Stamm, Amy (July 17, 2019). "'We Choose to Go to the Moon' and Other Apollo Speeches". National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- ^ Stafford & Cassutt, p. 469.

- ^ French & Burgess, p. 1397.

- ^ "Command Module, Apollo 10". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Saturn S-IVB-505N – Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Retrieved September 23, 2013.

- ^ David Dickinson (June 14, 2019). "Astronomers Might Have Found Apollo 10's "Snoopy" Module". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ Thompson, Mark (September 19, 2011). "The Search for Apollo 10's 'Snoopy'". Discovery News. Discovery Communications. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert Z. (September 20, 2011). "The Search for 'Snoopy': Astronomers & Students Hunt for NASA's Lost Apollo 10 Module". Space.com. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ "Apollo 10 – NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1969-043A". NASA. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Stooke, Phil (February 20, 2017). "Finding spacecraft impacts on the Moon". The Planetary Society. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ Launius & Johnston, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Orloff & Harland, p. 261.

Bibliography

[edit]- Apollo 10 Mission Report (PDF). Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA. 1969. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Apollo 10 Press Kit (PDF). NASA. May 7, 1969. Release No. 69-68. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Brooks, Courtney G.; Grimwood, James M.; Swenson, Loyd S. Jr. (1979). Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft (PDF). NASA History Series. Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA. ISBN 978-0-486-46756-6. LCCN 79001042. OCLC 4664449. NASA SP-4205. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Cernan, Gene; Davis, Don (2009) [1999]. The Last Man on the Moon: Astronaut Eugene Cernan and America's Race in Space (10th anniversary edition ebook ed.). St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-26351-5. OCLC 321015054.

- Chaikin, Andrew (1995) [1994]. A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts. Foreword by Tom Hanks. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-024146-4. OCLC 611666234.

- French, Francis; Burgess, Colin (2007). In the Shadow of the Moon: a Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965-1969 (eBook ed.). University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1128-5. OCLC 539472915.

- Glenday, Craig, ed. (2010). Guinness World Records 2010. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-59337-2. OCLC 436030244.

- Launius, Roger D.; Johnston, Andrew K. (2009). Smithsonian Atlas of Space Exploration. Bunker Hill Publishing. ISBN 978-0-06-156526-7. OCLC 883606901.

- Nelson, Craig (2009). Rocket Men: The Epic Story of the First Men on the Moon. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-02103-1. OCLC 1336245311.

- Orloff, Richard W. (2004) [First published 2000]. "Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference". NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans (PDF). NASA History Series. NASA. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. OCLC 651892628. NASA SP-2000-4029. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- Orloff, Richard W.; Harland, David M. (2006). Apollo: The Definitive Sourcebook. Praxis Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-387-30043-6. OCLC 315797584.

- Slayton, Donald K. "Deke"; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke! U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. Forge. ISBN 978-0-312-85503-1. OCLC 1301427286.

- Stafford, Thomas; Cassutt, Michael (2002). We Have Capture. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-58834-070-2. OCLC 539191452.

- Wilhelms, Don E. (1993). To a Rocky Moon: A Geologist's History of Lunar Exploration. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1065-8. OCLC 488684300.

External links

[edit]- "Apollo 10" at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- NSSDC Master Catalog at NASA

- Apollo 10 Flight Journal

NASA reports

- The Apollo Spacecraft: A Chronology Archived December 9, 2017, at the Wayback Machine NASA, NASA SP-4009

- "Apollo Program Summary Report" (PDF), NASA, JSC-09423, April 1975

- "Table 2-38. Apollo 10 Characteristics" from NASA Historical Data Book: Volume III: Programs and Projects 1969–1978 by Linda Neuman Ezell, NASA History Series (1988)

Multimedia

- Apollo 10: "To Sort Out the Unknowns" Official NASA/JSC documentary film, JSC-519 (1969)

- Apollo 10 16mm onboard film part 1, part 2 raw footage taken from Apollo 10 at the Internet Archive

- Mission Transcripts: Apollo 10 at NASA's Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

- Images from Apollo 10 Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine at NASA's Kennedy Space Center

- Apollo launch and mission videos at ApolloTV.net