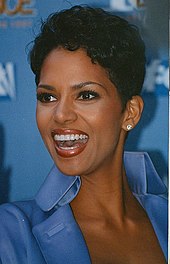

Halle Berry

Halle Berry | |

|---|---|

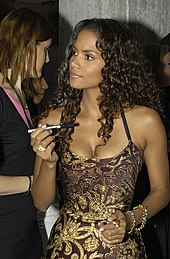

Berry in 2017 | |

| Born | Maria Halle Berry August 14, 1966 Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Education | Cuyahoga Community College |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1989–present |

| Spouses | |

| Partner | Gabriel Aubry (2005–2010) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | Full list |

Halle Maria Berry (/ˈhæli/ HAL-ee; born Maria Halle Berry; August 14, 1966) is an American actress. She began her career as a model and entered several beauty contests, finishing as the first runner-up in the Miss USA pageant and coming in sixth in the Miss World 1986. Her breakthrough film role was in the romantic comedy Boomerang (1992), alongside Eddie Murphy, which led to roles in The Flintstones (1994) and Bulworth (1998) as well as the television film Introducing Dorothy Dandridge (1999), for which she won a Primetime Emmy Award and a Golden Globe Award.

Berry established herself as one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood during the 2000s. For her performance of a struggling widow in the romantic drama Monster's Ball (2001), Berry became the only African-American woman to win the Academy Award for Best Actress, and the first woman of color. Berry took on high-profile roles such as Storm in four installments of the X-Men film series (2000–2014), the henchwoman of a robber in the thriller Swordfish (2001), Bond girl Jinx in Die Another Day (2002), and the title role in the much-derided Catwoman (2004).

A varying critical and commercial reception followed in subsequent years, with Perfect Stranger (2007), Cloud Atlas (2012) and The Call (2013) being among her notable film releases in that period. Berry launched a production company, 606 Films, in 2014 and has been involved in the production of a number of projects in which she performed, such as the CBS science fiction series Extant (2014–2015). She appeared in the action films Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017) and John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum (2019) and made her directorial debut with the Netflix drama Bruised (2020).

Berry has been a Revlon spokesmodel since 1996. She was formerly married to baseball player David Justice, singer-songwriter Eric Benét, and actor Olivier Martinez. She has two children, one with Martinez and another with model Gabriel Aubry.

Early life

Berry was born Maria Halle Berry in Cleveland, Ohio,[1] on August 14, 1966,[2] to Judith Ann (née Hawkins), an English immigrant from Liverpool,[3] and Jerome Jesse Berry, an African-American man.[1] Her name was legally changed to Halle Maria Berry at the age of five.[4] Her parents selected her middle name from Halle's Department Store, which was then a local landmark in Cleveland.[1] Berry's mother worked as a psychiatric nurse, and her father worked in the same hospital as an attendant in the psychiatric ward; he later became a bus driver.[1] They divorced when Berry was four years old, and she and her older sister Heidi Berry-Henderson[5] were raised exclusively by their mother.[1] She has been estranged from her father since childhood,[1][6] noting in 1992 that she did not even know if he was still alive.[5] Her father was abusive to her mother, and Berry has recalled witnessing her mother being beaten daily, kicked down stairs, and hit in the head with a wine bottle.[7] Berry said she was bullied as a kid, so she learned how to fight and protect herself.[8]

Berry grew up in Oakwood, Ohio,[9] and graduated from Bedford High School, where she was a cheerleader, honor student, editor of the school newspaper, and prom queen.[10] She worked in the children's department at Higbee's Department store. She then studied at Cuyahoga Community College. In the 1980s, she entered several beauty contests, winning Miss Teen All American 1985 and Miss Ohio USA in 1986.[11] She was the 1986 Miss USA first runner-up to Christy Fichtner of Texas.[11] In the Miss USA 1986 pageant interview competition, she said she hoped to become an entertainer or to have something to do with the media. Her interview was awarded the highest score by the judges.[12] She was the first African-American Miss World entrant in 1986, where she finished sixth and Trinidad and Tobago's Giselle Laronde was crowned Miss World.[13]

Career

Early work and breakthrough (1989–1999)

In 1989, Berry moved to New York City to pursue her acting ambitions.[14] During her early time there, she ran out of money and briefly lived in a homeless shelter and a YMCA.[15][16][17] Her situation improved by the end of that year, and she was cast in the role of model Emily Franklin in the short-lived ABC television series Living Dolls, which was shot in New York and was a spin-off of the hit series Who's the Boss?.[15] During the taping of Living Dolls, she lapsed into a coma and was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes.[18][19][20] After the cancellation of Living Dolls, she moved to Los Angeles.[15]

Berry's film debut was in a small role for Spike Lee's Jungle Fever (1991), in which she played Vivian, a drug addict.[1] That same year, Berry had her first co-starring role in Strictly Business. In 1992, Berry portrayed a career woman who falls for the lead character played by Eddie Murphy in the romantic comedy Boomerang. The following year, she caught the public's attention as a headstrong biracial slave in the TV adaptation of Queen: The Story of an American Family, based on the book by Alex Haley. Berry was also in the live-action Flintstones film as Sharon Stone, a sultry secretary who attempts to seduce Fred Flintstone.[21]

Berry tackled a more serious role, playing a former drug addict struggling to regain custody of her son in Losing Isaiah (1995), starring opposite Jessica Lange. She portrayed Sandra Beecher in Race the Sun (1996), which was based on a true story, shot in Australia, and co-starred alongside Kurt Russell in Executive Decision. Beginning in 1996, she was a Revlon spokeswoman for seven years and renewed her contract in 2004.[22][23]

She starred alongside Natalie Deselle Reid in the 1997 comedy film B*A*P*S. In 1998, Berry received praise for her role in Bulworth as an intelligent woman raised by activists who gives a politician (Warren Beatty) a new lease on life. The same year, she played the singer Zola Taylor, one of the three wives of pop singer Frankie Lymon, in the biopic Why Do Fools Fall in Love.

In the 1999 HBO biopic Introducing Dorothy Dandridge,[24] she portrayed Dorothy Dandridge, the first African American woman to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress. It was to Berry a heartfelt project that she introduced, co-produced and fought intensely for it to come through.[1] Berry won awards including a Primetime Emmy Award and Golden Globe Award.[11][25]

Worldwide recognition (2000–2004)

Berry portrayed the mutant superhero Storm in the film adaptation of the comic book series X-Men (2000) and its sequels, X2 (2003), X-Men: The Last Stand (2006) and X-Men: Days of Future Past (2014). In 2001, Berry appeared in the film Swordfish, which featured her first topless scene.[26] At first, she was opposed to a sunbathing scene in the film in which she would appear topless, but Berry eventually agreed. Some people attributed her change of heart to a substantial increase in the amount Warner Bros. offered her;[27] she was reportedly paid an additional $500,000 for the short scene.[28] Berry denied these stories, telling one interviewer that they amused her and "made for great publicity for the movie."[26][29] After turning down numerous roles that required nudity, she said she decided to make Swordfish because her then-husband, Eric Benét, supported her and encouraged her to take risks.[30]

Berry appeared as Leticia Musgrove, the troubled wife of an executed murderer (Sean Combs), in the 2001 feature film Monster's Ball. Her performance was awarded the National Board of Review and the Screen Actors Guild Award for Best Actress. She became the only African-American woman to win the Academy Award for Best Actress.[31] The NAACP issued the statement: "Congratulations to Halle Berry and Denzel Washington for giving us hope and making us proud. If this is a sign that Hollywood is finally ready to give opportunity and judge performance based on skill and not on skin color then it is a good thing."[32] This role generated controversy. Her graphic nude love scene with a racist character played by co-star Billy Bob Thornton was the subject of much media chatter and discussion among African Americans. Many in the African-American community were critical of Berry for taking the part.[30] Berry responded: "I don't really see a reason to ever go that far again. That was a unique movie. That scene was special and pivotal and needed to be there, and it would be a really special script that would require something like that again."[30]

Berry asked for a higher fee for Revlon advertisements after winning the Oscar. Ron Perelman, the cosmetics firm's chief, congratulated her, saying how happy he was that she modeled for his company. She replied, "Of course, you'll have to pay me more." Perelman stalked off in a rage.[33] In accepting her award, she gave an acceptance speech honoring previous black actresses who had never had the opportunity. She said, "This moment is so much bigger than me. This is for every nameless, faceless woman of color who now has a chance tonight because this door has been opened."[34]

As Bond girl Giacinta 'Jinx' Johnson in the 2002 blockbuster Die Another Day, Berry recreated a scene from Dr. No, emerging from the surf to be greeted by James Bond as Ursula Andress had 40 years earlier.[35] Lindy Hemming, costume designer on Die Another Day, had insisted that Berry wear a bikini and knife as a homage.[36] Berry has said of the scene: "It's splashy," "exciting," "sexy," "provocative" and "it will keep me still out there after winning an Oscar."[30][37] According to an ITV news poll, Jinx was voted the fourth toughest girl on screen of all time.[38] Berry was hurt during filming when debris from a smoke grenade flew into her eye. It was removed in a 30-minute operation.[39] After Berry won the Academy Award, rewrites were commissioned to give her more screentime for X2.[40]

She starred in the psychological thriller Gothika opposite Robert Downey, Jr. in November 2003, during which she broke her arm in a scene with Downey, who twisted her arm too hard. Production was halted for eight weeks.[41] It was a moderate hit at the United States box office, taking in $60 million; it earned another $80 million abroad.[42] Berry appeared in the nu metal band Limp Bizkit's music video for "Behind Blue Eyes" for the motion picture soundtrack for the film. The same year, she was named No. 1 in FHM's 100 Sexiest Women in the World poll.[43]

Berry starred as the title role in the film Catwoman,[42] for which she received US$12.5 million.[44] It is widely regarded by critics as one of the worst films ever made.[45] She was awarded the Worst Actress Razzie Award for her performance; she appeared at the ceremony to accept the award in person (while holding her Oscar from Monster's Ball)[46] with a sense of humor, considering it an experience of the "rock bottom" in order to be "at the top."[47] Holding the Academy Award in one hand and the Razzie in the other she said, "I never in my life thought that I would be up here, winning a Razzie! It's not like I ever aspired to be here, but thank you. When I was a kid, my mother told me that if you could not be a good loser, then there's no way you could be a good winner."[48]

Established actress and career fluctuations (2005–2013)

Her next film appearance was in the Oprah Winfrey-produced ABC television film Their Eyes Were Watching God (2005), an adaptation of Zora Neale Hurston's novel, with Berry portraying a free-spirited woman whose unconventional sexual mores upset her 1920s contemporaries in a small community. She received her second Primetime Emmy Award nomination for her role. Also in 2005, she served as an executive producer in Lackawanna Blues, and landed her voice for the character of Cappy, one of the many mechanical beings in the animated feature Robots.[49]

In the thriller Perfect Stranger (2007), Berry starred with Bruce Willis, playing a reporter who goes undercover to uncover the killer of her childhood friend. The film grossed a modest US$73 million worldwide, and received lukewarm reviews from critics, who felt that despite the presence of Berry and Willis, it is "too convoluted to work, and features a twist ending that's irritating and superfluous."[50] Her next 2007 film release was the drama Things We Lost in the Fire, co-starring Benicio del Toro, where she took on the role of a recent widow befriending the troubled friend of her late husband. The film was the first time in which she worked with a female director, Danish Susanne Bier, giving her a new feeling of "thinking the same way," which she appreciated.[51] While the film made US$8.6 million in its global theatrical run,[52] it garnered positive reviews from writers; The Austin Chronicle found the film to be "an impeccably constructed and perfectly paced drama of domestic and internal volatility" and felt that "Berry is brilliant here, as good as she's ever been."[53]

In April 2007, Berry was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in front of the Kodak Theatre at 6801 Hollywood Boulevard for her contributions to the film industry,[54] and by the end of the decade, she established herself as one of the highest-paid actresses in Hollywood, earning an estimated $10 million per film.[55]

In the independent drama Frankie and Alice (2010), Berry played the leading role of a young multiracial American woman with dissociative identity disorder struggling against her alter personality to retain her true self. The film received a limited theatrical release, to a mixed critical response. The Hollywood Reporter nevertheless described the film as "a well-wrought psychological drama that delves into the dark side of one woman's psyche" and found Berry to be "spellbinding" in it.[56] She earned the African-American Film Critics Association Award for Best Actress and a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama.[57][58] She next made part of a large ensemble cast in Garry Marshall's romantic comedy New Year's Eve (2011), with Michelle Pfeiffer, Jessica Biel, Robert De Niro, Josh Duhamel, Zac Efron, Sarah Jessica Parker, and Sofía Vergara, among many others. In the film, she took on the supporting role of a nurse befriending a man in the final stages (De Niro). While the film was panned by critics, it made US$142 million worldwide.[59]

In 2012, Berry starred as an expert diver tutor alongside then-husband Olivier Martinez in the little-seen thriller Dark Tide,[60] and led an ensemble cast opposite Tom Hanks and Jim Broadbent in The Wachowskis's epic science fiction film Cloud Atlas (2012), with each of the actors playing six different characters across a period of five centuries.[61] Budgeted at US$128.8 million, Cloud Atlas made US$130.4 million worldwide,[62] and garnered polarized reactions from both critics and audiences.[63]

Berry appeared in a segment of the independent anthology comedy Movie 43 (2013), which the Chicago Sun-Times called "the Citizen Kane of awful."[64][65] Berry found greater success with her next performance, as a 9-1-1 operator receiving a call from a girl kidnapped by a serial killer, in the crime thriller The Call (2013). Berry was drawn to "the idea of being a part of a movie that was so empowering for women. We don't often get to play roles like this, where ordinary people become heroic and do something extraordinary."[66] Manohla Dargis of The New York Times found the film to be "an effectively creepy thriller,"[67] while reviewer Dwight Brown felt that "the script gives Berry a blue-collar character she can make accessible, vulnerable and gutsy[...]."[68] The Call was a sleeper hit, grossing US$68.6 million around the globe.[69]

Continued film and television work (2014–present)

In 2014, Berry signed on to star and serve as a co-executive producer in CBS drama series Extant,[70] where she took on the role of Molly Woods, an astronaut who struggles to reconnect with her husband and android son after spending 13 months in space. The show ran for two seasons until 2015, receiving largely positive reviews from critics.[71][72][73] USA Today remarked: "She [Halle Berry] brings a dignity and gravity to Molly, a projected intelligence that allows you to buy her as an astronaut and to see what has happened to her as frightening rather than ridiculous. Berry's all in, and you float along."[74] Also in 2014, Berry launched a new production company, 606 Films, with producing partner Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas. It is named after the Anti-Paparazzi Bill, SB 606, that the actress pushed for and which was signed into law by California Governor Jerry Brown in the fall of 2013. The new company emerged as part of a deal for Berry to work in Extant.[75]

In the stand-up comedy concert film Kevin Hart: What Now? (2016), Berry appeared as herself, opposite Kevin Hart, attending a poker game event that goes horribly wrong.[76] She provided uncredited vocals to the song "Calling All My Lovelies" by Bruno Mars from his third studio album, 24K Magic (2016).[77] Kidnap, an abduction thriller Berry filmed in 2014, was released in 2017.[78] In the film, she starred as a diner waitress tailing a vehicle when her son is kidnapped by its occupants. Kidnap grossed US$34 million and garnered mixed reviews from writers, who felt that it "strays into poorly scripted exploitation too often to take advantage of its pulpy premise — or the still-impressive talents of [Berry]."[79] She next played an agent employed by a secret American spy organisation in the action comedy sequel Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017), as part of an ensemble cast, consisting of Colin Firth, Taron Egerton, Mark Strong, Julianne Moore, and Elton John. While critical response towards the film was mixed, it made US$414 million worldwide.[80]

Alongside Daniel Craig, Berry starred as a working-class mother during the 1992 Los Angeles riots in Deniz Gamze Ergüven's drama Kings (2017). The film found a limited theatrical release following its initial screening at the Toronto International Film Festival,[81] and as part of an overall lukewarm reception,[82] Variety noted: "It should be said that Berry has given some of the best and worst performances of the past quarter-century, but this is perhaps the only one that swings to both extremes in the same movie."[83] Berry competed against James Corden in the first rap battle on the first episode of TBS's Drop the Mic, originally aired on October 24, 2017.[84]

She played Sofia, an assassin, in the film John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum, which was released on May 17, 2019, by Lionsgate.[85] She is, as of February 2019, executive producer of the BET television series Boomerang, based on the film in which she starred. The series premiered February 12, 2019.[86]

Berry made her directorial debut with the feature Bruised in which she plays a disgraced MMA fighter named Jackie Justice, who reconnects with her estranged son. The film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2020[87] and was released on Netflix in November 2021.[88] Berry received a positive review from Deadline for her performance.[89]

In January 2023, Berry signed with Range Media Partners as a producer and director.[90]

Media image

Berry was ranked No. 1 on People's "50 Most Beautiful People in the World" list in 2003 after making the top ten seven times and appeared No. 1 on FHM's "100 Sexiest Women in the World" the same year.[91][92] She was named Esquire magazine's "Sexiest Woman Alive" in October 2008, about which she stated: "I don't know exactly what it means, but being 42 and having just had a baby, I think I'll take it."[93][94] Men's Health ranked her at No. 35 on their "100 Hottest Women of All-Time" list.[95] In 2009, she was voted #23 on Empire's 100 Sexiest Film Stars.[96] The same year, rapper Hurricane Chris released a song titled "Halle Berry (She's Fine)" extolling Berry's beauty and sex appeal.[97] At the age of 42 (in 2008), she was named the "Sexiest Black Woman" by Access Hollywood's "TV One Access" survey.[98][99][100][101] Born to an African-American father and a white mother, Berry has stated that her biracial background was "painful and confusing" when she was a young woman, and she made the decision early on to identify as a black woman because she knew that was how she would be perceived.[14]

Personal life

Berry dated Chicago dentist John Ronan from March 1989 to October 1991.[102] In November 1993, Ronan sued Berry for $80,000 in what he claimed were unpaid loans to help launch her career.[103] Berry contended that the money was a gift, and a judge dismissed the case because Ronan did not list Berry as a debtor when he filed for bankruptcy in 1992.[10]

According to Berry, a beating from a former abusive boyfriend during the filming of The Last Boy Scout in 1991 punctured her eardrum and caused her to lose 80% of her hearing in her left ear.[10] She has never named the abuser, but she said that he was someone "well known in Hollywood". In 2004, her former boyfriend Christopher Williams accused Wesley Snipes of being responsible for the incident, saying, "I'm so tired of people thinking I'm the guy [who did it]. Wesley Snipes busted her eardrum, not me."[104]

Berry first saw baseball player David Justice on TV playing in an MTV celebrity baseball game in February 1992. When a reporter from Justice's hometown of Cincinnati told her that Justice was a fan, Berry gave her phone number to the reporter to give to Justice.[10] Berry married Justice shortly after midnight on January 1, 1993.[105] Following their separation in February 1996, Berry stated publicly that she was so depressed that she had considered taking her own life.[106][107] Berry and Justice were divorced on June 20, 1997.[108]

In May 2000, Berry pleaded no contest to a charge of leaving the scene of a car accident; she was sentenced to three years' probation, fined $13,500, and ordered to perform 200 hours of community service.[109]

Berry married her second husband, singer-songwriter Eric Benét, on January 24, 2001, following a two-year courtship.[30][110] Benét underwent treatment for sex addiction in 2002.[111] By early October 2003, they had separated,[110] and their divorce was finalized on January 3, 2005.[112][113]

In November 2005, Berry began dating French-Canadian model Gabriel Aubry, whom she had met at a Versace photoshoot.[114] Berry gave birth to their daughter in March 2008.[115] On April 30, 2010, Berry and Aubry announced that their relationship had ended some months earlier.[116] In January 2011, Berry and Aubry became involved in a highly publicized custody battle,[117][118][119] centered primarily on Berry's desire to move with their daughter from Los Angeles, where Berry and Aubry resided, to France, the home of French actor Olivier Martinez, whom Berry had started dating in 2010, having met him while filming Dark Tide in South Africa.[120] Aubry objected to the move on the ground that it would interfere with their joint custody arrangement.[121] In November 2012, a judge denied Berry's request to move the couple's daughter to France.[122] Less than two weeks later, on November 22, 2012, Aubry and Martinez were both treated at a hospital for injuries after engaging in a physical altercation at Berry's residence. Martinez performed a citizen's arrest on Aubry and, because it was considered a domestic violence incident, was granted a temporary emergency protective order preventing Aubry from coming within 100 yards of Berry, Martinez, and the child with whom he shares custody with Berry, until November 29, 2012.[123] In turn, Aubry obtained a temporary restraining order against Martinez on November 26, 2012, asserting that the fight had begun when Martinez had threatened to kill Aubry if he did not allow the couple to move to France.[124] Leaked court documents included photos showing significant injuries to Aubry's face, which were widely displayed in the media.[125] On November 29, 2012, Berry's lawyer announced that Berry and Aubry had reached an amicable custody agreement in court.[126] In June 2014, a Superior Court ruling called for Berry to pay Aubry $16,000 a month in child support as well as a retroactive payment of $115,000 and $300,000 for Aubry's attorney fees.[127]

Berry and Martinez confirmed their engagement in March 2012,[128][129] and married in France on July 13, 2013.[130] In October 2013, Berry gave birth to their son.[131] In 2015, after two years of marriage, the couple announced they were divorcing.[132] The divorce was finalized in December 2016.[133] In August 2023, issues dealing with custody and child support were settled.[134]

Berry started dating American musician Van Hunt in 2020, which was revealed through her Instagram.[135][136]

Activism

Along with Pierce Brosnan, Cindy Crawford, Jane Seymour, Dick Van Dyke, Téa Leoni, and Daryl Hannah, Berry successfully fought in 2006 against the Cabrillo Port Liquefied Natural Gas facility that was proposed off the coast of Malibu.[137] Berry said, "I care about the air we breathe, I care about the marine life and the ecosystem of the ocean."[138] In May 2007, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the facility.[139] Hasty Pudding Theatricals gave her its 2006 Woman of The Year award.[140] Berry took part in a nearly 2,000-house cellphone-bank campaign for Barack Obama in February 2008.[141] In April 2013, she appeared in a video clip for Gucci's "Chime for Change" campaign that aims to raise funds and awareness of women's issues in terms of education, health, and justice.[142] In August 2013, Berry testified alongside Jennifer Garner before the California State Assembly's Judiciary Committee in support of a bill that would protect celebrities' children from harassment by photographers.[143] The bill passed in September.[144]

In May 2024, Berry advocated for more research and education on menopause by supporting a bill introduced by Senators Patty Murray and Lisa Murkowski. Berry said, "I'm in menopause, OK?... The shame has to be taken out of menopause. We have to talk about this very normal part of our life that happens. Our doctors can't even say the word to us, let alone walk us through the journey."[145]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Jungle Fever | Vivian | |

| Strictly Business | Natalie | ||

| The Last Boy Scout | Cory | ||

| 1992 | Boomerang | Angela Lewis | |

| 1993 | CB4 | Herself | |

| Father Hood | Kathleen Mercer | ||

| The Program | Autumn Haley | ||

| 1994 | The Flintstones | Sharon Stone | [21] |

| 1995 | Losing Isaiah | Khaila Richards | |

| 1996 | Executive Decision | Jean | |

| Girl 6 | Herself | ||

| Race the Sun | Miss Sandra Beecher | ||

| The Rich Man's Wife | Josie Potenza | ||

| 1997 | B*A*P*S | Denise "Nisi" | |

| 1998 | Bulworth | Nina | |

| Why Do Fools Fall in Love | Zola Taylor | ||

| Welcome to Hollywood | Herself | ||

| 2000 | X-Men | Ororo Munroe / Storm | |

| 2001 | Swordfish | Ginger Knowles | |

| Monster's Ball | Leticia Musgrove | ||

| 2002 | Die Another Day | Giacinta "Jinx" Johnson | |

| 2003 | X2 | Ororo Munroe / Storm | |

| Gothika | Miranda Grey | ||

| 2004 | Catwoman | Patience Phillips / Catwoman | |

| 2005 | Robots | Cappy | Voice role |

| 2006 | X-Men: The Last Stand | Ororo Munroe / Storm | |

| 2007 | Perfect Stranger | Rowena Price | |

| Things We Lost in the Fire | Audrey Burke | ||

| 2010 | Frankie & Alice | Frankie Murdoch / Alice / Genius | Also producer |

| 2011 | New Year's Eve | Nurse Aimee | |

| 2012 | Dark Tide | Kate Mathieson | |

| Cloud Atlas | Various Roles | ||

| 2013 | Movie 43 | Emily | Segment: "Truth Or Dare" |

| The Call | Jordan Turner | ||

| 2014 | X-Men: Days of Future Past | Ororo Munroe / Storm | |

| 2016 | Kevin Hart: What Now? | Money Berry | |

| 2017 | Kidnap | Karla Dyson | Also producer |

| Kings | Millie Dunbar | ||

| Kingsman: The Golden Circle | Ginger Ale | ||

| 2019 | John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum | Sofia Al-Azwar | |

| 2020 | Bruised | Jackie "Pretty Bull" Justice | Also director and producer |

| 2022 | Moonfall | Jocinda "Jo" Fowler | |

| 2023 | The Mothership | Sara Morse | Unreleased |

| 2024 | The Union | Roxanne Hall | |

| Never Let Go | Momma | Also executive producer | |

| TBA | Crime 101 | TBA | Filming |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Living Dolls | Emily Franklin | Main Cast |

| 1991 | Amen | Claire | Episode: "Unforgettable" |

| A Different World | Jaclyn | Episode: "Love, Hillman-Style" | |

| They Came from Outer Space | Rene | Episode: "Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow" | |

| Knots Landing | Debbie Porter | Recurring Cast: Season 13 | |

| 1993 | NAACP Image Awards | Herself / Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| Alex Haley's Queen | Queen Jackson Haley | Episode: "Part 1-3" | |

| 1994 | A Century of Women | Herself | Episode: "Part 1-2" |

| 1995 | Solomon & Sheba | Nikhaule / Queen Sheba | Television film |

| 1996 | Martin | Herself | Episode: "Where the Party At" |

| 1996–1997 | Essence Awards | Herself / Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| 1997 | World Music Awards | Herself / Host | Main Host |

| 1998 | Behind the Music | Herself | Episode: "Lionel Richie" |

| Intimate Portrait | Episode: "Halle Berry" | ||

| Mad TV | Herself / Host | Episode: "Halle Berry" | |

| The Wedding | Shelby Coles | Episode: "Part 1-2" | |

| Frasier | Betsy | Voice role; Episode: "Room Service" | |

| 1999 | Introducing Dorothy Dandridge | Dorothy Dandridge | Television film; also executive producer |

| 1999–2008 | Biography | Herself | Recurring Guest |

| 2001 | Great Streets | Episode: "The Champs Elysees" | |

| 2002 | E! True Hollywood Story | Episode: "The Bond Girls" | |

| Mad TV | Episode: "Episode #8.7" | ||

| The Bernie Mac Show | Episode: "Handle Your Business" | ||

| 2003 | Ant & Dec's Saturday Night Takeaway | Episode: "Episode #2.8" | |

| Saturday Night Live | Herself / Host | Episode: "Halle Berry / Britney Spears" | |

| Style Star | Herself | Episode: "Halle Berry" | |

| Punk'd | Episode: "Episode #2.5" | ||

| Making the Video | Episode: "Limp Bizkit: Behind Blue Eyes" | ||

| 2004 | Rove | Episode: "Episode #5.9" | |

| Getaway | Episode: "Getaway Goes to Hollywood" | ||

| 4Pop | Episode: "Pärstäkerroin voittaa aina" | ||

| 2005 | Their Eyes Were Watching God | Janie Crawford | Television film |

| 2009 | NAACP Image Awards | Herself / Co-Host | Main Co-Host |

| 2011 | The Simpsons | Herself | Voice role; Episode: "Angry Dad: The Movie" |

| 2012 | Sesame Street | Episode: "Get Lost, Mr. Chips" | |

| 2014–2015 | Extant | Molly Woods | Main role; 26 episodes (also executive producer) |

| 2017 | Drop the Mic | Herself | Episode: "Halle Berry vs. James Corden & Anthony Anderson vs. Usher" |

| 2021 | American Masters | Episode: "How It Feels To Be Free" | |

| 2022 | Soul of a Nation | Episode: "Soul of a Nation Presents: Screen Queens Rising" | |

| Celebrity IOU | Episode: "Halle Berry's Beautiful Gift" |

Video game

| Year | Game | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Catwoman | Patience Phillips/Catwoman |

Music videos

| Year | Song | Artist |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | "(Meet) The Flintstones" | The B-52s |

| 1998 | "Ghetto Supastar (That Is What You Are)" | Pras featuring Ol' Dirty Bastard and Mya |

| 2003 | "Behind Blue Eyes" | Limp Bizkit |

Awards and nominations

See also

- List of African American firsts

- List of female film and television directors

- List of LGBT-related films directed by women

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Halle Berry". Inside the Actors Studio. Bravo, October 29, 2007.

- ^ Although Britannica Kids gives a 1968 birthdate Archived August 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, (from the original on August 17, 2012), she stated in interviews prior to August 2006 that she would turn 40 then. See: FemaleFirst, DarkHorizons, FilmMonthly Archived September 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, and see also Profile, cbsnews.com; accessed May 5, 2007.

- ^ Echo, Liverpool (March 25, 2002). "Halle's Liverpool roots". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- ^ "First Generation". Genealogy.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Lovece, Frank (July 7, 1992). "Halle Berry Is Poised to Become Major Star". Newspaper Enterprise Association/Reading Eagle. Reading, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "Showbiz Bytes 28-01-03". The Age. January 28, 2003. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ Gennis, Sadie (February 21, 2015). "Halle Berry Opens Up About Childhood Experience with Domestic Violence". TVGuide. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ FOX 13 Seattle (August 20, 2024). Halle Berry Gets Real About Action Movie Injuries!. Retrieved November 3, 2024 – via YouTube.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The Woman Who Would Be Queen | PEOPLE.com Archived June 12, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Schneider, Karen S. (May 13, 1996). "Hurts So Bad". People. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c "Halle Berry Biography". People. Archived from the original on August 29, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ "Miss USA 1986 Scores". Pageant Almanac. Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- ^ Sanello, Frank (2003). Halle Berry: A Stormy Life. Tebbo. ISBN 978-1-7424-4654-7.

- ^ a b Talmon, Noelle. "The 15 Sexiest Black Actresses In Hollywood". Starpulse.com. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2015.

- ^ a b c Current Biography Yearbook. New York City: H.W. Wilson Company. 1999. pp. 62–64. ISBN 978-0-8242-0988-9.

- ^ "Halle Berry: From homeless shelter to Hollywood fame" (April 2007). Reader's Digest (White Plains, New York USA: Reader's Digest Association, Inc.), p. 89: Reader's Digest: "Is it true that when you moved to New York to begin your acting career, you lived in a shelter?" Berry: "Very briefly. ... I wasn't working for a while."

- ^ US Weekly (April 27, 2007). "Halle Berry was homeless. Berry slept at a shelter in NYC after her mom refused to send her money."

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (May 17, 2006). Beyond 'I'm a Diabetic', Little Common Ground Archived August 25, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times; accessed December 24, 2010.

- ^ Hoskins, Mike (April 25, 2013). "Revisiting the Great Halle Berry Diabetes Ruckus" Archived January 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, DiabetesMine.com; accessed March 20, 2013.

- ^ "Halle Berry - Actress & Model with Type 1 Diabetes". www.diabetes.co.uk. January 15, 2019. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ a b "Berry: Ripe for success" Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, March 25, 2002; accessed February 19, 2007.

- ^ Bayot, Jennifer (December 1, 2002). "Private Sector; A Shaker, Not a Stirrer, at Revlon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Revlon – Supplier News – renewed its contract with actress Halle Berry; to introduce the Pink Happiness Spring 2004 Color Collection – Brief Article" Archived August 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine (December 15, 2003), CNET Networks; accessed December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Halle Berry Brings the Passion and Pain of Dorothy Dandridge to HBO Movie". Jet. August 23, 1999. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ Parish, James Robert (October 29, 2001). The Hollywood Book of Death: The Bizarre, Often Sordid, Passings of More than 125 American Movie and TV Idols, Contemporary Books of McGraw Hill; ISBN 0-8092-2227-2

- ^ a b Hyland, Ian (September 2, 2001) "The Diary: Halle's bold glory", Sunday Mirror; accessed July 5, 2009.

- ^ Davies, Hugh (February 7, 2001). "Halle Berry earns extra £357,000 for topless scene" Archived April 17, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph; accessed April 29, 2008.

- ^ D'Souza, Christa (December 31, 2001). "And the winner is..." Archived April 17, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph; accessed August 16, 2010.

- ^ "Swordfish: Interview With Halle Berry" Archived January 5, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Cinema.com. Accessed May 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Halle's big year" (November 2002), Ebony.

- ^ Paula Bernstein (February 25, 2014). "The Diversity Gap in the Academy Awards in Infographic Form". IndieWire. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ "NAACP Congratulates Halle Berry, Denzel Washington" (March 2002), U.S. Newswire; accessed October 29, 2015.

- ^ Davies, Hugh (April 2, 2002). "Berry seeks higher adverts fee" Archived April 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Telegraph; accessed April 1, 2008.

- ^ Poole, Oliver (March 26, 2002). "Oscar night belongs to Hollywood's black actors", The Telegraph; accessed April 1, 2008.

- ^ "Berry recreates a Bond girl icon" Archived April 18, 2018, at the Wayback Machine (April 12, 2002), Telegraph Observer.

- ^ Cesar G. Soriano; Kelly Carter (November 13, 2002). "Latest Bond Girl is dressed to kill". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Die Another Day Special Edition DVD 2002.

- ^ "Halle Berry`s `Jinx` named fourth toughest female screen icon" Archived December 15, 2004, at the Wayback Machine. MI6 News.

- ^ Hugh Davies (April 10, 2002). "Halle Berry hurt in a blast during Bond film scene." Archived November 16, 2012, at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph; accessed April 1, 2008.

- ^ "The X-Men 2 panel" Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (July 30, 2002), joblo.com; accessed March 12, 2008.

- ^ "Halle Berry talks about Gothika", iVillage.co.uk; accessed October 29, 2015.

- ^ a b Sharon Waxman (July 21, 2004). "Making Her Leap Into an Arena Of Action; Halle Berry Mixes Sexiness With Strength" Archived March 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times. Accessed April 1, 2008.

- ^ "FHM Readers Name Scarlett Johansson World's Sexiest Woman; Actress Tops Voting in FHM's 100 Sexiest Women in the World 2006 Readers' Poll" (March 27, 2006), Business Wire; accessed January 1, 2008.

- ^ David Gritten (July 30, 2004). "Curse of the Best Actress Oscar", The Telegraph; accessed October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Hollywood's Top 5 Worst Movies Ever Made - Entertainment & Stars". January 10, 2012. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (February 27, 2005). "Razzie Berry gives a fruity performance". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on April 22, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ Piccalo, Gina (November 1, 2007). "A career so strong it survived Catwoman". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 16, 2010. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ^ "Halle Berry Biography: Page 2" Archived January 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, People.com; accessed December 20, 2007.

- ^ Bob Grimm (March 17, 2005). "CGI City" Archived December 10, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Tucson Weekly; accessed October 28, 2015.

- ^ "Perfect Stranger". Rotten Tomatoes. April 13, 2007. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Things We Lost in the Fire", Entertainment Weekly, October 15, 2007.

- ^ "Things We Lost in the Fire (2007) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "Film Review: Things We Lost in the Fire". Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Halle Berry Gets Star on Hollywood Walk of Fame", foxnews.com, April 4, 2007; accessed December 13, 2007.

- ^ "Top 10 Highest-Paid Actresses". CBS News. June 3, 2009. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ "Frankie & Alice -- Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Cane, Clay (December 14, 2010). "African-American Film Critics Association Honors Halle Berry and 'The Social Network'". BET. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ "Halle Berry". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ "New Year's Eve (2011)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 22, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ "Dark Tide". Rotten Tomatoes. March 30, 2012. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Meet Halle Berry and Tom Hanks' Cloud Atlas characters". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Cloud Atlas (2012) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (September 9, 2012). "Cloud Atlas gets lengthy ovation, but are Oscars on the cards". Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (January 25, 2013). "There's awful and THEN there's 'Movie 43'". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "Movie 43 (2013)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ Grant, Kimberly (March 13, 2013). "Berry, Chestnut Expound on The Call Roles - and more". South Florida Times. Fort Lauderdale. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (March 14, 2013). "Life-Altering Plea for Help". The New York Times. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ Brown, Dwight (March 15, 2013). "The Call". HuffPost. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "The Call (2013)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 18, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- ^ "Halle Berry To Topline CBS Series 'Extant'", deadline.com, October 4, 2013.

- ^ "Extant". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 15, 2019. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "CBS Sets Premiere Dates for 'Under the Dome', New Drama 'Extant'" Archived March 17, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, variety.com, January 15, 2014.

- ^ "CBS Sets Summer Slate: Halle Berry's 'Extant' Premiere Pushed a Week" Archived February 18, 2023, at the Wayback Machine (March 11, 2014), TheWrap.com.

- ^ "With Halle Berry in its orbit, 'Extant' has potential". USA Today. Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ "Halle Berry, Elaine Goldsmith-Thomas Name 606 Films Shingle After Anti-Paparazzi Bill", deadline.com, March 6, 2014.

- ^ "Kevin Hart: What Now?". Archived from the original on October 6, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Roth, Madeline. "Bruno Mars Still Can't Get Halle Berry To Call Him Back". MTV News. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ^ Giles, Jeff (August 3, 2017). "Dark Tower Condemned". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ "Kidnap (2017)". Rotten Tomatoes. August 4, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Toronto International Film Festival unveils first slate of films for 2017". Toronto International Film Festival. July 25, 2017. Archived from the original on July 27, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Kings Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (September 14, 2017). "Toronto Film Review: 'Kings'". Variety. Retrieved August 27, 2024.

- ^ Longeretta, Emily (October 25, 2017). "Watch Halle Berry Crush James Corden in Rap Battle". Us Weekly. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "John Wick: Chapter Three Release Date Set for 2019". ComingSoon.net. September 14, 2017. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ^ Patten, Dominic (September 24, 2018). "Halle Berry & Lena Waithe Add Serious EP Spin To BET's 'Boomerang' Reboot". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (June 24, 2020). "Toronto Film Festival Reveals Plan For Slimline 2020 Edition With Mix Of Physical & Digital Screenings; Kate Winslet, Idris Elba & Mark Wahlberg Movies Among First Wave". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 1, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (September 11, 2020). "Toronto 2020 Starts With Knockout: Netflix In Final Talks To Acquire Halle Berry-Directed MMA Drama 'Bruised' In 8-Figure WW Deal". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 12, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ Hammond, Pete (November 14, 2021). "'Bruised' Review: Halle Berry Directs Herself Into No-Holds-Barred Portrayal Of MMA Fighter Looking For Redemption – AFI Fest". Deadline. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved November 14, 2021.

- ^ Grobar, Matt (January 31, 2023). "Halle Berry Signs With Range Media Partners". Deadline. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Gary Susman (May 1, 2003). X-Appeal . Entertainment Weekly; accessed October 6, 2012.

- ^ Howard, Tom (January 27, 2003). "100 Sexiest Women in the World 2003 – the Top Ten". FHM. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- ^ "Halle Berry Is the Sexiest Woman Alive, 2008" Archived May 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (October 10, 2008), Esquire.com; accessed May 10, 2012.

- ^ "Esquire names Halle Berry 'sexiest woman alive'" Archived August 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (October 7. 2008). The Brownsville Herald; accessed May 10, 2012.

- ^ The 100 Hottest Women of All-Time Archived August 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Men's Health; accessed January 3, 2012.

- ^ "The 100 Sexiest Movie Stars: #23. Halle Berry" Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Empireonline.com; accessed May 10, 2012.

- ^ "Halle Berry (She's Fine)" Archived June 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Youtube.com; accessed October 6, 2012.

- ^ "TV One Access Counts Down 'Sexiest Black Woman Alive'". Access Online. March 6, 2009. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ "Halle Berry Is The Sexiest Black Woman Alive!". The Rundown TV. July 7, 2008. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ "Halle Berry Crowned 'The Sexiest Black Woman Alive'". Starpulse.com. July 2, 2008. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ "TV One Declares Halle as Sexiest Black Woman Alive". urban-hoopla.com. July 4, 2008. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ "Actress Halle Berry hit with $80,000 lawsuit by Chicago dentist", Jet, December 13, 1993.

- ^ "Berry steps toward stardom with 'Isaiah'". The Milwaukee Sentinel. March 24, 1995.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Berry Beaten by Snipes?". E! Online. January 15, 2004. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ Don O'Briant, "Ringing in '93 - with wedding bells" Archived January 27, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Atlanta Journal (January 10, 1993), Nl.newsbank.com; accessed March 7, 2010.

- ^ Listfield, Emily (April 1, 2007). "My Sights Are Set on Motherhood". Parade. Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ^ Hamida Ghafour (March 21, 2002). "I was close to ending it all, says actress", Telegraph.co.uk; accessed April 1, 2008.

- ^ "Divorce between Halle Berry, David Justice final" Archived February 3, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, The Albany Herald, June 25, 1997; accessed October 29, 2015.

- ^ "Halle Berry Gets Probation, Fine for Leaving Scene of Crash". Los Angeles Times. May 11, 2000. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Stephen M. Silverman (October 2, 2003). "Halle Berry, Eric Benet Split". People. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "Benet: 'Berry Is Lying'". Contactmusic.com. June 27, 2006. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (January 10, 2005). "Halle Berry Finalizes Split from Benet". People. Archived from the original on August 17, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "Eric Benét's Confessions". People. Vol. 64, no. 2. July 11, 2005. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "Halle Berry Steps Out with Her New Man". People. February 15, 2006. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "Halle Berry Has a Baby Girl". People. March 16, 2008. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Triggs, Charlotte; Jordan, Julie (May 2, 2010). "Source: Halle Berry 'Kicked Gabriel Out' Months Ago". People. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Fleeman, Mike (January 18, 2011). "Halle Berry's Ex Gabriel Aubry Files for Joint Custody of Daughter". People. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ Fleeman, Mike (January 31, 2011). "Halle Berry to Fight for Custody of Daughter". People. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Stephen M. Silverman (June 21, 2012). "Halle Berry to Pay Gabriel Aubry $20,000 a Month in Child Support: Report". People. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ "The Carousel of Hope Ball". Marie Claire. October 25, 2010. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ Nudd, Tim (October 16, 2012). "Halle Berry: Why I Want to Leave the Country". People. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ "Halle Berry Can't Move to France with Daughter: Report". People. November 9, 2012. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ Michaud, Sarah (November 22, 2012). "Gabriel Aubry Arrested After Brawl with Olivier Martinez". People. Archived from the original on November 24, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- ^ "Gabriel Aubry describes confrontation with Halle Berry's fiancé". Los Angeles Times. November 26, 2012. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "Gabriel Aubry: Halle Berry's Fiancé Threatened to KILL ME". tmz.com. TMZ. November 26, 2012. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2015.

- ^ Finn, Natalie (November 29, 2012). "Halle Berry and Gabriel Aubry Reach 'Amicable Agreement' in Court". EOnline. Archived from the original on September 8, 2014. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ^ "Halle Berry to Pay $16,000 Each Month in Child Support". abcnews. Archived from the original on June 10, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ Are Halle Berry and Olivier Martinez getting married? Archived September 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Marie Claire; accessed January 29, 2012.

- ^ "Olivier Martinez confirms engagement to Halle Berry, clears up ring debate, opens Villa Azur on South Beach this weekend" Archived March 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, The Miami Herald, March 10, 2012; accessed March 10, 2012.

- ^ Ehrich Dowd, Kathy; Mikelbank, Peter (July 13, 2013). "Halle Berry Is Married: Photos". People. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Duke, Alan (October 6, 2013). "Halle Berry gives birth to a son". CNN. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ Zauzmer, Emily (October 27, 2015). "Halle Berry and Olivier Martinez Are Divorcing After Two Years of Marriage". People. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Fisher, Kendall (December 30, 2016). "Halle Berry Finalizes Divorce from Olivier Martinez". E! News. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ Melendez, Miguel (August 23, 2023). "Halle Berry To Pay Olivier Martinez $8,000 Monthly Child Support In Divorce Settlement". ET Canada. Archived from the original on September 29, 2023. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

- ^ "Halle Berry Calls Boyfriend Van Hunt Her 'Superstar': 'I'll Be Ya Groupie Baby'". People. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Weaver, Hilary (May 16, 2021). "All About Halle Berry's Boyfriend, Van Hunt". ELLE. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ "Actors join protest against project off Malibu", NBC News, October 23, 2005.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (April 11, 2007). "Halle Berry, Others Protest Natural Gas Facility". People. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "The Santa Barbara Independent Cabrillo Port Dies a Santa Barbara Flavored Death" Archived November 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, The Santa Barbara Independent, May 24, 1007.

- ^ "And the Pudding Pot goes to..." Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (February 2, 2006), Harvard University Gazette; accessed January 1, 2008.

- ^ "Halle Berry, Ted Kennedy: 'Move On' for Obama" (February 29, 2008), Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Karmali, Sarah (April 16, 2013). "Blake Lively and Halle Berry Join Gucci's Chime For Change". Vogue. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ^ Child, Ben (August 15, 2013). "Jennifer Garner joins Halle Berry's fight for new anti-paparazzi law in California". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ^ Pulver, Andrew (September 26, 2013). "Anti-paparazzi bill backed by Halle Berry now California law". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- ^ Khan, Mariam; Kindelan, Katie (May 2, 2024). "Halle Berry shouts 'I'm in menopause' on Capitol Hill as she fights for funding to improve women's care". ABC News. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

General bibliography

- Banting, Erinn. Halle Berry, Weigl Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1-59036-333-7.

- Gogerly, Liz. Halle Berry, Raintree, 2005. ISBN 1-4109-1085-7.

- Naden, Corinne J. Halle Berry, Sagebrush Education Resources, 2001. ISBN 0-613-86157-4.

- O'Brien, Daniel. Halle Berry, Reynolds & Hearn, 2003. ISBN 1-903111-38-2.

- Sanello, Frank. Halle Berry: A Stormy Life, Virgin Books, 2003. ISBN 1-85227-092-6.

- Schuman, Michael A. Halle Berry: Beauty Is Not Just Physical, Enslow, 2006. ISBN 0-7660-2467-9.

External links

- Halle Berry on Facebook

- Halle Berry at IMDb

- Halle Berry at People.com

- Halle Berry at TV Guide

- Halle Berry at the TCM Movie Database

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Halle Berry

- 1966 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American actresses

- 21st-century American actresses

- Actresses from Cleveland

- 20th-century African-American actresses

- African-American beauty pageant winners

- African-American female models

- African-American television producers

- African-American film directors

- American film actresses

- American people of English descent

- American television actresses

- American voice actresses

- American women film producers

- American women television producers

- Best Actress Academy Award winners

- Best Miniseries or Television Movie Actress Golden Globe winners

- Cuyahoga Community College alumni

- Female models from Ohio

- Models from Cleveland

- Film producers from Ohio

- Miss USA 1986 delegates

- Miss World 1986 delegates

- Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Leading Role Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Miniseries or Television Movie Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- Outstanding Performance by a Lead Actress in a Miniseries or Movie Primetime Emmy Award winners

- People from Cuyahoga County, Ohio

- People with type 1 diabetes

- Silver Bear for Best Actress winners

- Television producers from Ohio

- 21st-century African-American actresses

- The Second City Training Center alumni