Mary Curzon, Baroness Curzon of Kedleston

The Lady Curzon of Kedleston | |

|---|---|

| |

| Viceregal-Consort of India | |

| In office 6 January 1899 – 18 November 1905 | |

| Monarchs | Victoria Edward VII |

| Governor- General | The Lord Curzon of Kedleston |

| Preceded by | The Countess of Elgin |

| Succeeded by | The Countess of Minto |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mary Victoria Leiter 27 May 1870 Chicago, Illinois, United States |

| Died | 18 July 1906 (aged 36) Carlton House Terrace, London, England |

| Resting place | Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Margaret Howard, Countess of Suffolk (sister) |

Mary Victoria Curzon, Baroness Curzon of Kedleston, CI (née Leiter; 27 May 1870 – 18 July 1906), was an American heiress who married George Curzon, the future Viceroy of India.

In America

[edit]

by Alexandre Cabanel

Mary Victoria Leiter was born in Chicago, the eldest daughter of Mary Theresa (née Carver) and Levi Ziegler Leiter, the wealthy co-founder of Field and Leiter dry goods business, and later partner in the Marshall Field retail empire. On her father's side, she was of Swiss-German descent.[1][2][3] Her family moved to Washington, D.C. in 1881 and entered the exclusive circle of official society there. They lived for several years in the former home of James G. Blaine on Dupont Circle before moving into the Leiter House. The family also spent time at Lake Geneva, earning her the sobriquet "Lake Geneva Princess."[4]

She was taught dancing, singing, music, and art at home by tutors and learned the French language from her French governess. A Columbia University professor taught her history, arithmetic, and chemistry. Travel and prolonged residence abroad cultivated her powers of observation and breadth of mental vision at an early age. As stated in 1901, her education "gave her that poise and finish that made her so charming to men and women of mature and brilliant intellect."[5] She was 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall. Her appearance was described at her wedding: "a face of unusual beauty, oval in shape, with dark grey eyes, straight black brows, a sweet, sensitive mouth, a prettily shaped nose, and a low forehead with fine black hair brushed simply away from it and emphasising its whiteness."[5]

Her debut was in winter of 1888. She was regarded an equal in beauty and breeding, and, frequently, superior in manner and intellect of daughters of better known and longer established families in eastern U.S. society. Prior to her marriage, her closest friend was Frances Folsom Cleveland, six years her senior and the wife of a much older President Grover Cleveland.[6]

In England

[edit]

by William Logsdail

Mary was introduced to London society in 1890. She met a young man, George Curzon, a Conservative Member of Parliament who was thirty-five years old, had been representing Southport for eight years, and was heir to the Barony of Scarsdale. The position he had made for himself through his own talents was of more interest to her than his eventual inheritance, and his high reputation as a writer on the political questions in the East particularly attracted her admiration. Mary Leiter and George Curzon were married on 22 April 1895 at St. John's Episcopal Church, Lafayette Square, Washington, D.C., by Bishop Talbot, assisted by the Rev. Dr. Mackay Smith, the pastor of the church.[7]

She played an important role in the reelection of her husband to Parliament that autumn and many thought that his success was due more to the winning smiles and irresistible charm of his wife than to his own speeches. They had three daughters, Mary Irene (later Lady Ravensdale), in 1896, Cynthia (first wife of Sir Oswald Mosley), on 23 August 1898, lastly, Alexandra, on 20 April 1904 (wife of Edward "Fruity" Metcalfe, the best friend, best man, and equerry of Edward VIII); best known as Baba Metcalfe.

In India

[edit]

by Franz von Lenbach

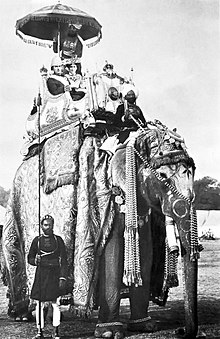

Her husband accepted the position of Viceroy of India and was elevated to the Peerage of Ireland as Baron Curzon of Kedleston in the summer of 1898 at age thirty-nine. As Vicereine of India, his wife held the highest official title in the Indian Empire that a woman could hold, as did Lady Wellesley, also an American wife of a prominent British man.[5] On 30 December they arrived in Bombay to the greetings of royal salutes and great excitement. She instantly made an impression of beauty and respect that soon spread all over India. She gained the title vicereine, as wife of the viceroy, a title of the British aristocracy. They were greeted in Calcutta a few days later with great enthusiasm. It was estimated that over one hundred thousand people witnessed the magnificent spectacle of their reception at Government House. The Indian poet Ram Sharma referred to her in his welcome address to Lord Curzon of Kedleston, as:

"A rose of roses bright

A vision of embodied light."

Another declared her to be:

"Like a diamond set in gold

the full moon in a clear autumnal sky."[8]

In 1901 Charles Turner first raised the "Lady Curzon" rose in her honor, which was a hybrid (R. macrantha x R. rugosa Rubra). It has a soft iridescent pink/violet shade, 10 cm flowers, and a sweet scent.[9]

In 1902 Lord Curzon organized the Delhi Durbar to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII, "the grandest pageant in history", which created a tremendous sensation. At the state ball Mary wore an extravagant coronation gown, by the House of Worth of Paris, known as Lady Curzon's peacock dress, stitched of gold cloth embroidered with peacock feathers with a blue/green beetle wing in each eye, which many mistook for emeralds, tapping into their own fantasies about the wealth of millionaire heiresses, Indian potentates and European royalty.[10] The skirt was trimmed with white roses and the bodice with lace.[11] She wore a huge diamond necklace and a large brooch of diamonds and pearls. She wore a tiara crown with a pearl tipping each of its high diamond points. It was reported that as she walked through the hall the crowd was breathless.[12][13] This dress is now on display at the Curzon estate, Kedleston Hall.

Lady Curzon contributed to the design of the exquisitely rich and beautiful coronation robe of Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom,[14] made from gold fabric woven and embroidered in the same factory in Chandni Chauk Delhi where she ordered all the materials for her own state gowns. The factory owner said that she had the rarest taste of any woman he knew, and that she was the best dressed woman in the world—an opinion shared by others.

Lady Curzon was an invaluable commercial agent for the manufacturers of the higher class of fabrics and art objects in India. She wore Indian fabrics, and as a result many of them became fashionable in Calcutta and other Indian cities as well as in London, Paris, and the capitals of Europe. She placed orders for her friends and strangers. She assisted the silk weavers, embroiderers, and other artists to adapt their designs, patterns, and fabrics to the requirements of modern fashions.

She kept several of the best artists in India busy with orders and soon saw the results of her efforts, reviving skilled arts that almost had been forgotten. Lady Curzon was tutored in Urdu by the Mohyal patriarch Bakhshi Ram Dass Chhibber.[15]

Progressive medical reforms were initiated by English women in India under the leadership of the Marchioness of Dufferin and Lady Curzon by supplying women doctors and hospitals for women. There is a Lady Curzon Hospital in Bangalore, shown to the right.

William Eleroy Curtis, Chicago journalist and author, dedicated his book Modern India thus: "To Lady Curzon, An ideal American woman".[16]

On 4 November 1902 Lady Curzon wrote from Viceroy's Camp, Simla, to Lady Randolph Churchill advising her on the appropriate headgear to wear in Delhi, saying that she is looking forward to seeing her and that she will not need an ayah in addition to her maid.[17]

In 1903 she sailed on a yacht from Karachi for a tour of the Persian Gulf with Lord Curzon, Ignatius Valentine Chirol, young Winston Churchill and other notable guests.

In 1904, Lady Curzon traveled by train with Lord Curzon to Dhaka and toured the Shahbagh area in a fleet of Dechamp Tonneau-model 1902 automobiles.

Lady Curzon learned about the great one-horned rhinoceroses of Kaziranga from her tea-plantation friends and wanted to see them. In the winter of 1904 she visited the Kaziranga area,[18] and saw some of their hoof marks, but was disappointed by not having seen a single rhinoceros. It was reported that the noted Assamese animal tracker, Balaram Hazarika, showed Lady Curzon around Kaziranga and impressed upon her the urgent need for its conservation.[19] Concerned about the dwindling numbers of rhinoceros, she asked her husband to take the necessary action to save the rhinoceros, which he did. The Kaziranga Proposed Reserve Forest thus was created. Later it was developed into the Kaziranga National Park.

Private life

[edit]

The Curzons had three daughters but no son, as much as Lord Curzon wished for one.[11] Lady Curzon's demanding social responsibilities, the tropical climate, a prolonged near-fatal infection following a miscarriage, and fertility-related surgery eroded her health. Despite several trips to England to convalesce, her health continued to decline.[11] Following their return to England after Curzon's resignation in August 1905, her health was rapidly failing. She died on 18 July 1906 at home at 1 Carlton House Terrace, Westminster, London, at age thirty-six.[20][11]

It is said that Lady Curzon, after having seen the Taj Mahal on a moonlit night, exclaimed in her bewilderment that she was ready to embrace an immediate death if someone promised to erect such a memorial on her grave.[21]

Following Lady Curzon's death, in 1906, Lord Curzon had a memorial chapel built in his late wife's honour, attached to All Saints, the parish church at Kedleston Hall. Lady Curzon is buried, with her husband, in the family vault beneath it. The design of the chapel, by G. F. Bodley, does not resemble the Taj Mahal, but is in the decorated Gothic style. It was completed in 1913.[22]

In the chapel Curzon expressed his grief at his wife's premature death by charging the sculptor, Sir Bertram Mackennal, to create a marble effigy for her tomb which: "expressed as might be possible in marble, the pathos of his wife's premature death and to make the sculpture emblematic of the deepest emotion."[23] Later, Curzon's own effigy was added to lie beside that of his wife's, as his remains do in the vault beneath. Curzon's second wife chose to be buried in the churchyard outside.

The Curzons' youngest daughter, Alexandra Naldera, was conceived in July 1903 at Naldehra, 25 km from Shimla,[24] perhaps after a high altitude game of golf.[25] She was born on 20 March 1904.[26] and became best known as "Baba", an Indian name for baby or little one. In 1925 she married Major Edward Dudley Metcalfe, the best friend and equerry of Edward VIII.[27] Lord Curzon's second wife and stepmother to the daughters, Grace Curzon wrote a book of Reminiscences.[28][29]

In popular culture

[edit]Mary Curzon and her three daughters are considered to be part of the inspiration for the fictional characters Lady Grantham and her three daughters, particularly in respect to the inability to produce a male heir, and the importance of a woman's virtue in the Downton Abbey television series written by Julian Fellowes and produced by ITV.[30]

Lady Curzon Soup, a curry-flavored turtle soup, was named after her. In 1977 a food article in The New York Times noted its popularity in Germany and, according to a letter to the columnist, that Lady Curzon always had sherry added to it.[31]

Biographies

[edit]- de Courcy, Anne (2003), The Viceroy's Daughters, The Lives of the Curzon Sisters, Harper Collins Publishers, ISBN 0-06-093557-X

- Bradley, John, ed. (1986), Lady Curzon's India: Letters of a Vicereine, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-78701-2

- Nicolson, Nigel (1977), Lady Curzon, New York: Harper & Row, ISBN 0-297-77390-9, retrieved 14 March 2007

References

[edit]- ^ Wilson, A.N. (2005). After the Victorians. Hutchinson. p. 596. ISBN 9780091794842.

- ^ The Listener. British Broadcasting Corporation. 1977.

- ^ Bradford, Sarah (9 August 1995). "Lady Alexandra Metcalfe". The Independent. London. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ Lahey, Sarah T. (26 February 2020). "A Lake Geneva Princess". At The Lake Magazine.

- ^ a b c Peacock, Virginia Tatnall (1901). "Mary Victoria Leiter (Baroness Curzon of Kedleston)". Famous American Belles of the Nineteenth Century. J.B. Lippincott – via Access Genealogy.

For the second time within the century an American woman has risen to viceregal honors. . .Lady Wellesley had but to follow the leadership of a man of recognized ability and established fame, while Lady Curzon walks side by side with the man who is making that steep ascent

- ^ De Courcy, Anne (2003). The Viceroy's Daughters: The Lives of the Curzon Sisters. Harper Collins. p. 61. ISBN 0-06-093557-X. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ^ Thomas, Denis (1977). "Cobbold's Diary". The Listener. Vol. 98. British Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Virginia Tatnall Peacock. Famous American Belles of the Nineteenth Century. J.B. Lippincott, New York, 1901., pp.264 - 287.Full text

- ^ Pro artists, Roses/Lady Curzon Roses/Lady Curzon

- ^ Thomas, Nicola J. (1 July 2007). "Embodying Imperial Spectacle: Dressing Lady Curzon, Vicereine of India 1899-1905". Cultural Geographies. 14:369-400 (3): 391. Bibcode:2007CuGeo..14..369T. doi:10.1177/1474474007078205. S2CID 143628645.

- ^ a b c d Marian Fowler (1987). Below the Peacock Fan: First Ladies of the Raj. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-80748-2. OL 3236422W. Wikidata Q126672688.

- ^ "Curzon's Will". Time Magazine. 3 August 1925. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Finding Aids to Official Records of the Smithsonian Institution, Accession 87-156, National Portrait Gallery, Office of Exhibitions, Exhibition Records, 1975–1979, Mary, Lady Curzon: Portrait of Mary Victoria Leiter, Baroness Curzon of Kedelston (Lady A. Metcalf), Once a Proconsul, Always a Proconsul, M. Beerbohm (All Souls' College), Silver Medallion Commemorating Curzon's Viceroyalty of India (Viscount Scarsdale), Badge of the Order of the Crown of India (Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth) Peacock Dress of Mary Curzon (Mus. of London), Lady Curzon's Ball Costume by Jean Worth (Museum of Costume, Bath) two Photos: Viceregal Lodge at Simla (India Office Records), Five Photos of Procession of Rajahs and Maharajas through Delhi (India Off. Library), Photograph of Lady Curzon wearing Peacock Dress (Lady Alexandra Metcalfe) Film Clip: Lord and Lady Arriving at Great Delhi Durbar [1]

- ^ Thomas, Nicola J. (1 July 2007). "Embodying Imperial Spectacle: Dressing Lady Curzon, Vicereine of India 1899-1905". Cultural Geographies. 14:369-400 (3): 388. Bibcode:2007CuGeo..14..369T. doi:10.1177/1474474007078205. S2CID 143628645.

- ^ General Mohyal Sabha, 2005-06, A-9, Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi-110067, "MEMBERS OF MOHYALS" [2] Archived 17 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Curtis, William Eleroy (1904). Modern India. Project Gutenberg EBook. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ^ Churchill College, CHURCHILL ARCHIVES CENTRE, CHAR 28/66/36 retrieved 23 March 2007 [3]

- ^ "100 Years of Kazaringa National Park". Archived from the original on 14 February 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Bhaumik, Subir (18 February 2005). "Kaziranga's centenary celebrations". BBC News, South Asia.

- ^ "Maximilian Genealogy Master Database, Mary Victoria LEITER, 2000". peterwestern.f9.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ SR Shaheed DOHS Banani (25 October 2004) "Lady Curzon's wish", The Daily Star, Vol. 5 Num 153, Dhaka [4]

- ^ *The National Trust (1988; repr. 1997). Kedleston Hall. page 60.

- ^ *The National Trust (1988; repr. 1997). Kedleston Hall. page 61.

- ^ Cory, Charlotte (29 December 2002). "The Delhi Durbar 1903 Revisited". Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ^ "Wildflower Hall, Shimla in the Himalayas". Retrieved 31 July 2015.

The former abode of Lord Kitchener, Wildflower Hall exudes the ambience of a colonial Hill Station home, with luxurious rooms, a welcoming lounge, a bridge room and a library.

- ^ Tompsett, Brian C (ed.). "Alexandra Naldera Curzon". Royal Genealogy Database at Hull. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ "Milestones: June 8, 1925 - TIME". Time. 8 June 1925. Archived from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Davies, Matt (18 March 2002). "John Singer Sargent's Grace Elvina". Retrieved 18 March 2007.

Daughter of J. Monroe Hinds, United States Minister to Brazil, Grace Elvina was married firstly to Alfred Duggan of Buenos Aires. Widowed by Duggan, she then married secondly on 2 January 1917 to George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (1859 -1925). Grace was the author of a book of Reminiscences.

- ^ "John Singer Sargent's George Nathaniel, Marquess Curzon of Kedleston".

- ^ Shattuck, Katherine; Mandeville, Hubert (5 January 2015). "'Downton Abbey' and History: A Look Back". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ Claiborne, Craig (19 September 1977). "De Gustibus: More on Lady Curzon's Turtle Soup". The New York Times. p. 58. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Thomas, Nicola J. (2004) "Broadening the Boundaries of Biography and Geography: Lady Curzon, Vicereine of India 1898–1905", ##Journal of Historical Geography

- Thomas, Nicola J. (2006), "American Vicereine of India", in Lambert, David; Lester, Alan (eds.), Imperial Lives across the Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-84770-4

External links

[edit]- "On the Death of Lady Curzon", poem by Florence Earle Coates

- British baronesses

- 1870 births

- 1906 deaths

- Companions of the Order of the Crown of India

- Recipients of the Kaisar-i-Hind Medal

- Curzon family

- American emigrants to the United Kingdom

- English people of Swiss descent

- British people of American descent

- British philanthropists

- Viceregal consorts of India

- People from Chicago

- People from Dupont Circle

- 1900s in British India