Buddhist meditation

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Mindfulness |

|---|

|

|

|

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism. The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā ("mental development")[note 1] and jhāna/dhyāna (a state of meditative absorption resulting in a calm and luminous mind).[note 2]

Buddhists pursue meditation as part of the path toward liberation from defilements (kleshas) and clinging and craving (upādāna), also called awakening, which results in the attainment of Nirvana.[note 3] The Indian Buddhist schools relied on numerous meditation techniques to attain meditative absorption, some of which remain influential in certain modern schools of Buddhism. Classic Buddhist meditations include anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing), asubha bhavana ("reflections on repulsiveness");[1] reflection on pratityasamutpada (dependent origination); anussati (recollections, including anapanasati), the four foundations of mindfulness,[2][3][4][5] and the divine abodes (including loving-kindness and compassion). These techniques aim to develop various qualities including equanimity, sati (mindfulness), samadhi (unification of mind) c.q. samatha (tranquility) and vipassanā (insight); and are also said to lead to abhijñā (supramundane powers). These meditation techniques are preceded by and combined with practices which aid this development, such as moral restraint and right effort to develop wholesome states of mind.

While some of the classic techniques are used throughout the modern Buddhist schools, the later Buddhist traditions also developed numerous other forms of meditation. One basic classification of meditation techniques divides them into samatha (calming the mind) and vipassana (cultivating insight). In the Theravada traditions emphasizing vipassana, these are often seen as separate techniques,[note 4] while Mahayana Buddhism generally stresses the union of samatha and vipassana.[6] Both Mahayana and Theravada traditions share some practices, like breath meditation and walking meditation. East Asian Buddhism developed a wide range of meditation techniques, including the Zen methods of zazen and huatou, the Pure Land practices of nianfo and guanfo, and the Tiantai method of "calming and insight" (zhǐguān). Tibetan Buddhism and other forms of Vajrayana mainly rely on the tantric practice of deity yoga as a central meditation technique.[note 5] These are taught alongside other methods like Mahamudra and Dzogchen.

Etymology

[edit]The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are bhāvanā (mental development)[note 1] and jhāna/dhyāna.[note 2]

Possible influence from pre-Buddhist India

[edit]Modern Buddhist studies have attempted to reconstruct the meditation practices of early Buddhism, mainly through philological and text critical methods using the early canonical texts.[7]

According to Indologist Johannes Bronkhorst, "the teaching of the Buddha as presented in the early canon contains a number of contradictions,"[8] presenting "a variety of methods that do not always agree with each other,"[9] containing "views and practices that are sometimes accepted and sometimes rejected."[8] These contradictions are due to the influence of non-Buddhist traditions on early Buddhism. One example of these non-Buddhist meditative methods found in the early sources is outlined by Bronkhorst:

The Vitakkasanthāna Sutta of the Majjhima Nikāya and its parallels in Chinese translation recommend the practicing monk to ‘restrain his thought with his mind, to coerce and torment it’. Exactly the same words are used elsewhere in the Pāli canon (in the Mahāsaccaka Sutta, Bodhirājakumāra Sutta and Saṅgārava Sutta) in order to describe the futile attempts of the Buddha before his enlightenment to reach liberation after the manner of the Jainas.[7]

According to Bronkhorst, such practices which are based on a "suppression of activity" are not authentically Buddhist, but were later adopted from the Jains by the Buddhist community.

The two major traditions of meditative practice in pre-Buddhist India were the Jain ascetic practices and the various Vedic Brahmanical practices. There is still much debate in Buddhist studies regarding how much influence these two traditions had on the development of early Buddhist meditation. The early Buddhist texts mention that Gautama trained under two teachers known as Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, both of them taught formless jhanas or mental absorptions, a key practice of Theravada Buddhist meditation.[10] Alexander Wynne considers these figures historical persons associated with the doctrines of the early Upanishads.[11] Other practices which the Buddha undertook have been associated with the Jain ascetic tradition by the Indologist Johannes Bronkhorst including extreme fasting and a forceful "meditation without breathing".[12] According to the early texts, the Buddha rejected the more extreme Jain ascetic practices in favor of the middle way.

Pre-sectarian Buddhism

[edit]

Early Buddhism, as it existed before the development of various schools, is called pre-sectarian Buddhism. Its meditation-techniques are described in the Pali Canon and the Chinese Agamas.

Preparatory practices

[edit]Meditation and contemplation are preceded by preparatory practices.[2] As described in the Noble Eightfold Path, right view leads to leaving the household life and becoming a wandering monk. Sila, morality, comprises the rules for right conduct. Sense restraint and right effort, c.q. the four right efforts, are important preparatory practices. Sense restraint means controlling the response to sensual perceptions, not giving in to lust and aversion but simply noticing the objects of perception as they appear.[13] Right effort aims to prevent the arising of unwholesome states, and to generate wholesome states. By following these preparatory steps and practices, the mind becomes set, almost naturally, for the onset of dhyana.[14][15][note 6]

Sati/smrti (mindfulness)

[edit]An important quality to be cultivated by a Buddhist meditator is mindfulness (sati). Mindfulness is a polyvalent term which refers to remembering, recollecting and "bearing in mind". It also relates to remembering the teachings of the Buddha and knowing how these teachings relate to one's experiences. The Buddhist texts mention different kinds of mindfulness practice.

The Pali Satipatthana Sutta and its parallels as well as numerous other early Buddhist texts enumerates four subjects (satipaṭṭhānas) on which mindfulness is established: the body (including the four elements, the parts of the body, and death); feelings (vedana); mind (citta); and phenomena or principles (dhammas), such as the five hindrances and the seven factors of enlightenment. Different early texts give different enumerations of these four mindfulness practices. Meditation on these subjects is said to develop insight.[16]

According to Bronkhorst, there were originally two kinds of mindfulness, "observations of the positions of the body" and the four satipaṭṭhānas, the "establishment of mindfulness," which constituted formal meditation.[17] Bhikkhu Sujato and Bronkhorst both argue that the mindfulness of the positions of the body (which is actually "clear comprehension") wasn't originally part of the four satipatthana formula, but was later added to it in some texts.[17]

Bronkhorst (1985) also argues that the earliest form of the satipaṭṭhāna sutta only contained the observation of the impure body parts under mindfulness of the body, and that mindfulness of dhammas was originally just the observation of the seven awakening factors.[18][note 7] Sujato's reconstruction similarly only retains the contemplation of the impure under mindfulness of the body, while including only the five hindrances and the seven awakening factors under mindfulness of dhammas.[19][note 8] According to Analayo, mindfulness of breathing was probably absent from the original scheme, noting that one can easily contemplate the body's decay taking an external object, that is, someone else's body, but not be externally mindfull of the breath, that is, someone else's breath. [20]

According to Grzegorz Polak, the four upassanā have been misunderstood by the developing Buddhist tradition, including Theravada, to refer to four different foundations. According to Polak, the four upassanā do not refer to four different foundations of which one should be aware, but are an alternate description of the jhanas, describing how the samskharas are tranquilized:[21]

- the six sense-bases which one needs to be aware of (kāyānupassanā);

- contemplation on vedanās, which arise with the contact between the senses and their objects (vedanānupassanā);

- the altered states of mind to which this practice leads (cittānupassanā);

- the development from the five hindrances to the seven factors of enlightenment (dhammānupassanā).

Anussati (recollections)

[edit]

Anussati (Pāli; Sanskrit: Anusmriti) means "recollection," "contemplation," "remembrance," "meditation" and "mindfulness."[23] It refers to specific meditative or devotional practices, such as recollecting the sublime qualities of the Buddha or anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing), which lead to mental tranquillity and abiding joy. In various contexts, the Pali literature and Sanskrit Mahayana sutras emphasize and identify different enumerations of recollections.

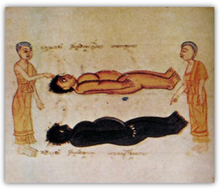

Asubha bhavana (reflection on unattractiveness)

[edit]Asubha bhavana is reflection on "the foul"/unattractiveness (Pāli: asubha). It includes two practices, namely cemetery contemplations, and Paṭikkūlamanasikāra, "reflections on repulsiveness". Patikulamanasikara is a Buddhist meditation whereby thirty-one parts of the body are contemplated in a variety of ways. In addition to developing sati (mindfulness) and samādhi (concentration, dhyana), this form of meditation is considered to be conducive to overcoming desire and lust.[24]

Anapanasati (mindfulness of breathing)

[edit]Anapanasati, mindfulness of breathing, is a core meditation practice in Theravada, Tiantai and Chan traditions of Buddhism as well as a part of many mindfulness programs. In both ancient and modern times, anapanasati by itself is likely the most widely used Buddhist method for contemplating bodily phenomena.[25]

The Ānāpānasati Sutta specifically concerns mindfulness of inhalation and exhalation, as a part of paying attention to one's body in quietude, and recommends the practice of anapanasati meditation as a means of cultivating the Seven Factors of Enlightenment: sati (mindfulness), dhamma vicaya (analysis), viriya (persistence), which leads to pīti (rapture), then to passaddhi (serenity), which in turn leads to samadhi (concentration) and then to upekkhā (equanimity). Finally, the Buddha taught that, with these factors developed in this progression, the practice of anapanasati would lead to release (Pali: vimutti; Sanskrit mokṣa) from dukkha (suffering), in which one realizes nibbana.[citation needed]

Dhyāna/jhāna

[edit]Many scholars of early Buddhism, such as Vetter, Bronkhorst and Anālayo, see the practice of jhāna (Sanskrit: dhyāna) as central to the meditation of Early Buddhism.[2][3][4] According to Bronkhorst, the oldest Buddhist meditation practice are the four dhyanas, which lead to the destruction of the asavas as well as the practice of mindfulness (sati).[7] According to Vetter, the practice of dhyana may have constituted the core liberating practice of early Buddhism, since in this state all "pleasure and pain" had waned.[2] According to Vetter,

[P]robably the word "immortality" (a-mata) was used by the Buddha for the first interpretation of this experience and not the term cessation of suffering that belongs to the four noble truths [...] the Buddha did not achieve the experience of salvation by discerning the four noble truths and/or other data. But his experience must have been of such a nature that it could bear the interpretation "achieving immortality".[26]

Alexander Wynne agrees that the Buddha taught a kind of meditation exemplified by the four dhyanas, but argues that the Buddha adopted these from the Brahmin teachers Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, though he did not interpret them in the same Vedic cosmological way and rejected their Vedic goal (union with Brahman). The Buddha, according to Wynne, radically transformed the practice of dhyana which he learned from these Brahmins which "consisted of the adaptation of the old yogic techniques to the practice of mindfulness and attainment of insight".[27] For Wynne, this idea that liberation required not just meditation but an act of insight, was radically different from the Brahminic meditation, "where it was thought that the yogin must be without any mental activity at all, ‘like a log of wood’."[28]

Four rupa-jhanas

[edit]Qualities

[edit]In the sutras, jhāna is entered when one 'sits down cross-legged and establishes mindfulness'. According to Buddhist tradition, it may be supported by ānāpānasati, mindfulness of breathing, a core meditative practice which can be found in almost all schools of Buddhism. The Suttapiṭaka and the Agamas describe four stages of rūpa jhāna. Rūpa refers to the material realm, in a neutral stance, as different from the kāma-realm (lust, desire) and the arūpa-realm (non-material realm).[29] While interpreted in the Theravada-tradition as describing a deepening concentration and one-pointedness, originally the jhānas seem to describe a development from investigating body and mind and abandoning unwholesome states, to perfected equanimity and watchfulness,[5] an understanding which is retained in Zen and Dzogchen.[15][5] The stock description of the jhānas, with traditional and alternative interpretations, is as follows:[5][note 9]

- First jhāna:

- Separated (vivicceva) from desire for sensual pleasures, separated (vivicca) from [other] unwholesome states (akusalehi dhammehi, unwholesome dhammas[30]), a bhikkhu enters upon and abides in the first jhana, which is [mental] pīti ("rapture," "joy") and [bodily] sukha ("pleasure"; also: 'lasting', in contrast to 'transient' (dukkha)) "born of viveka" (traditionally, "seclusion"; alternatively, "discrimination" (of dhamma's)[31][note 10]), accompanied by vitarka-vicara (traditionally, initial and sustained attention to a meditative object; alternatively, initial inquiry and subsequent investigation[34][35][36] of dhammas (defilements[37] and wholesome thoughts[38][note 11]); also: "discursive thought"[note 12]).

- Second jhāna:

- Again, with the stilling of vitarka-vicara, a bhikkhu enters upon and abides in the second jhana, which is [mental] pīti and [bodily] sukha "born of samadhi" (samadhi-ji; trad. born of "concentration"; altern. "knowing but non-discursive [...] awareness,"[46] "bringing the buried latencies or samskaras into full view"[47][note 13]), and has sampasadana ("stillness,"[49] "inner tranquility"[44][note 14]) and ekaggata (unification of mind,[49] awareness) without vitarka-vicara;

- Third jhāna:

- With the fading away of pīti, a bhikkhu abides in upekkhā (equanimity," "affective detachment"[44][note 15]), sato (mindful) and [with] sampajañña ("fully knowing,"[50] "discerning awareness"[51]). [Still] experiencing sukha with the body, he enters upon and abides in the third jhana, on account of which the noble ones announce, "abiding in [bodily] pleasure, one is equanimous and mindful".

- Fourth jhāna:

- With the abandoning of [the desire for] sukha ("pleasure") and [aversion to] dukkha ("pain"[52][51]) and with the previous disappearance of [the inner movement between] somanassa ("gladness,"[53]) and domanassa ("discontent"[53]), a bhikkhu enters upon and abides in the fourth jhana, which is adukkham asukham ("neither-painful-nor-pleasurable,"[52] "freedom from pleasure and pain"[54]) and has upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi (complete purity of equanimity and mindfulness).[note 16]

Interpretation

[edit]According to Richard Gombrich, the sequence of the four rupa-jhanas describes two different cognitive states.[56][note 17][57] Alexander Wynne further explains that the dhyana-scheme is poorly understood.[58] According to Wynne, words expressing the inculcation of awareness, such as sati, sampajāno, and upekkhā, are mistranslated or understood as particular factors of meditative states,[58] whereas they refer to a particular way of perceiving the sense objects.[58][note 18][note 19] Polak notes that the qualities of the jhanas resemble the bojjhaṅgā, the seven factors of awakening]], arguing that both sets describe the same essential practice.[15] Polak further notes, elaborating on Vetter, that the onset of the first dhyana is described as a quite natural process, due to the preceding efforts to restrain the senses and the nurturing of wholesome states.[15][14]

Upekkhā, equanimity, which is perfected in the fourth dhyana, is one of the four Brahma-vihara. While the commentarial tradition downplayed the Brahma-viharas, Gombrich notes that the Buddhist usage of the brahma-vihāra, originally referred to an awakened state of mind, and a concrete attitude toward other beings which was equal to "living with Brahman" here and now. The later tradition took those descriptions too literally, linking them to cosmology and understanding them as "living with Brahman" by rebirth in the Brahma-world.[60] According to Gombrich, "the Buddha taught that kindness – what Christians tend to call love – was a way to salvation."[61]

Arupas

[edit]In addition to the four rūpajhānas, there are also meditative attainments which were later called by the tradition the arūpajhānas, though the early texts do not use the term dhyana for them, calling them āyatana (dimension, sphere, base). They are:

- The Dimension of infinite space (Pali ākāsānañcāyatana, Skt. ākāśānantyāyatana),

- The Dimension of infinite consciousness (Pali viññāṇañcāyatana, Skt. vijñānānantyāyatana),

- The Dimension of infinite nothingness (Pali ākiñcaññāyatana, Skt. ākiṃcanyāyatana),

- The Dimension of neither perception nor non-perception (Pali nevasaññānāsaññāyatana, Skt. naivasaṃjñānāsaṃjñāyatana).

- Nirodha-samāpatti, also called saññā-vedayita-nirodha, 'extinction of feeling and perception'.

These formless jhanas may have been incorporated from non-Buddhist traditions.[3][62]

Jhana and insight

[edit]Various early sources mention the attainment of insight after having achieved jhana. In the Mahasaccaka Sutta, dhyana is followed by insight into the four noble truths. The mention of the four noble truths as constituting "liberating insight" is probably a later addition.[63][26][3][62] Discriminating insight into transiency as a separate path to liberation may be a later development,[64][65] under pressure of developments in Indian religious thinking, which saw "liberating insight" as essential to liberation.[66] This may also have been due to an over-literal interpretation by later scholastics of the terminology used by the Buddha,[67] and to the problems involved with the practice of dhyana, and the need to develop an easier method.[68][63][26][3][62] Collett Cox and Damien Keown question the existence of a dichotomy between dhyana and insight, arguing that samadhi is a key aspect of the later Buddhist process of liberation, which cooperates with insight to remove the āsavas.[69][70]

Brahmavihāra

[edit]Another important meditation in the early sources are the four Brahmavihāra (divine abodes) which are said to lead to cetovimutti, a "liberation of the mind".[71] The four Brahmavihāra are:

- Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active good will towards all;[72][73]

- Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta, it is identifying the suffering of others as one's own;[72][73]

- Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it, it is a form of sympathetic joy;[72]

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.[72][73]

According to Anālayo:

The effect of cultivating the brahmavihāras as a liberation of the mind finds illustration in a simile which describes a conch blower who is able to make himself heard in all directions. This illustrates how the brahmavihāras are to be developed as a boundless radiation in all directions, as a result of which they cannot be overruled by other more limited karma.[74]

The practice of the four divine abodes can be seen as a way to overcome ill-will and sensual desire and to train in the quality of deep concentration (samadhi).[75]

Early Buddhism

[edit]Traditionally, Eighteen schools of Buddhism are said to have developed after the time of the Buddha. The Sarvastivada school was the most influential, but the Theravada is the only school that still exists.

Samatha (serenity) and vipassana (insight)

[edit]The Buddha is said to have identified two paramount mental qualities that arise from wholesome meditative practice:

- "serenity" or "tranquillity" (Pali: samatha; Sanskrit: samadhi) which steadies, composes, unifies and concentrates the mind;

- "insight" (Pali: vipassanā) which enables one to see, explore and discern "formations" (conditioned phenomena based on the five aggregates).[note 20]

The Buddha is said to have extolled serenity and insight as conduits for attaining Nibbana (Pali; Skt.: Nirvana), the unconditioned state as in the "Kimsuka Tree Sutta" (SN 35.245), where the Buddha provides an elaborate metaphor in which serenity and insight are "the swift pair of messengers" who deliver the message of Nibbana via the Noble Eightfold Path.[note 21]

In the Threefold training, samatha is part of samadhi, the eight limb of the threefold path, together with sati, mindfulness. According to Mahāsi Sayādaw, tranquility meditation can lead to the attainment of supernatural powers such as psychic powers and mind reading while insight meditation can lead to the realisation of nibbāna.[76]

In the Pāli Canon, the Buddha never mentions independent samatha and vipassana meditation practices; instead, samatha and vipassana are two qualities of mind, to be developed through meditation.[note 22] Nonetheless, according to the Theravada tradition some meditation practices (such as contemplation of a kasina object) favor the development of samatha, others are conducive to the development of vipassana (such as contemplation of the aggregates), while others (such as mindfulness of breathing) are classically used for developing both mental qualities.[77]

In the "Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta" (AN 4.170), Ven. Ananda reports that people attain arahantship using serenity and insight in one of three ways:

- they develop serenity and then insight (Pali: samatha-pubbangamam vipassanam)

- they develop insight and then serenity (Pali: vipassana-pubbangamam samatham)

- they develop serenity and insight in tandem (Pali: samatha-vipassanam yuganaddham) as in, for instance, obtaining the first jhana, and then seeing in the associated aggregates the three marks of existence, before proceeding to the second jhana.[78]

While the Nikayas state that the pursuit of vipassana can precede the pursuit of samatha, according to the Burmese Vipassana movement vipassana be based upon the achievement of stabilizing "access concentration" (Pali: upacara samadhi). According to the Theravada tradition, through the meditative development of serenity, one is able to suppress obscuring hindrances; and, with the suppression of the hindrances, it is through the meditative development of insight that one gains liberating wisdom.[79]

Theravāda

[edit]

Sutta Pitaka and early commentaries

[edit]The oldest material of the Theravāda tradition on meditation can be found in the Pali Nikayas, and in texts such as the Patisambhidamagga which provide commentary to meditation suttas like the Anapanasati sutta.

Buddhaghosa

[edit]An early Theravāda meditation manual is the Vimuttimagga ('Path of Freedom', 1st or 2nd century).[80] The most influential presentation though, is that of the 5th-century Visuddhimagga ('Path of Purification') of Buddhaghoṣa, which seems to have been influenced by the earlier Vimuttimagga in his presentation.[81]

The Visuddhimagga's doctrine reflects Theravāda Abhidhamma scholasticism, which includes several innovations and interpretations not found in the earliest discourses (suttas) of the Buddha.[82][83] Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga includes non-canonical instructions on Theravada meditation, such as "ways of guarding the mental image (nimitta)," which point to later developments in Theravada meditation.[84]

The text is centered around kasina-meditation, a form of concentration-meditation in which the mind is focused on a (mental) object.[85] According to Thanissaro Bhikkhu, "[t]he text then tries to fit all other meditation methods into the mold of kasina practice, so that they too give rise to countersigns, but even by its own admission, breath meditation does not fit well into the mold."[85] In its emphasis on kasina-meditation, the Visuddhimagga departs from the Pali Canon, in which dhyana is the central meditative practice, indicating that what "jhana means in the commentaries is something quite different from what it means in the Canon."[85]

The Visuddhimagga describes forty meditation subjects, most being described in the early texts.[86] Buddhaghoṣa advises that, for the purpose of developing concentration and consciousness, a person should "apprehend from among the forty meditation subjects one that suits his own temperament" with the advice of a "good friend" (kalyāṇa-mittatā) who is knowledgeable in the different meditation subjects (Ch. III, § 28).[87] Buddhaghoṣa subsequently elaborates on the forty meditation subjects as follows (Ch. III, §104; Chs. IV–XI):[88]

- ten kasinas: earth, water, fire, air, blue, yellow, red, white, light, and "limited-space".

- ten kinds of foulness: "the bloated, the livid, the festering, the cut-up, the gnawed, the scattered, the hacked and scattered, the bleeding, the worm-infested, and a skeleton".

- ten recollections: Buddhānussati, the Dhamma, the Sangha, virtue, generosity, the virtues of deities, death (see the Upajjhatthana Sutta), the body, the breath (see anapanasati), and peace (see Nibbana).

- four divine abodes: mettā, karuṇā, mudita, and upekkha.

- four immaterial states: boundless space, boundless perception, nothingness, and neither perception nor non-perception.

- one perception (of "repulsiveness in nutriment")

- one "defining" (that is, the four elements)

When one overlays Buddhaghosa's 40 meditative subjects for the development of concentration with the Buddha's foundations of mindfulness, three practices are found to be in common: breath meditation, foulness meditation (which is similar to the Sattipatthana Sutta's cemetery contemplations, and to contemplation of bodily repulsiveness), and contemplation of the four elements. According to Pali commentaries, breath meditation can lead one to the equanimous fourth jhanic absorption. Contemplation of foulness can lead to the attainment of the first jhana, and contemplation of the four elements culminates in pre-jhana access concentration.[89]

Contemporary Theravāda

[edit]

Vipassana and/or samatha

[edit]The role of samatha in Buddhist practice, and the exact meaning of samatha, are points of contention and investigation in contemporary Theravada and western vipassanan. Burmese vipassana teachers have tended to disregard samatha as unnecessary, while Thai teachers see samatha and vipassana as intertwined.

The exact meaning of samatha is also not clear, and westerners have started to question the received wisdom on this.[15][5] While samatha is usually equated with the jhanas in the commentarial tradition, scholars and practitioners have pointed out that jhana is more than a narrowing of the focus of the mind. While the second jhana may be characterized by samadhi-ji, "born of concentration," the first jhana sets in quite naturally as a result of sense-restraint,[14][15] while the third and fourth jhana are characterized by mindfulness and equanimity.[3][62][15] Sati, sense-restraint and mindfulness are necessary preceding practices, while insight may mark the point where one enters the "stream" of development which results in vimukti, release.[90]

According to Anālayo, the jhanas are crucial meditative states which lead to the abandonment of hindrances such as lust and aversion; however, they are not sufficient for the attainment of liberating insight. Some early texts also warn meditators against becoming attached to them, and therefore forgetting the need for the further practice of insight.[91] According to Anālayo, "either one undertakes such insight contemplation while still being in the attainment, or else one does so retrospectively, after having emerged from the absorption itself but while still being in a mental condition close to it in concentrative depth."[92]

The position that insight can be practiced from within jhana, according to the early texts, is endorsed by Gunaratna, Crangle and Shankaman.[93][94][95] Anālayo meanwhile argues, that the evidence from the early texts suggest that "contemplation of the impermanent nature of the mental constituents of an absorption takes place before or on emerging from the attainment".[96]

Arbel has argued that insight precedes the practice of jhana.[5]

Vipassana movement

[edit]Particularly influential from the twentieth century onward has been the Burmese Vipassana movement, especially the "New Burmese Method" or "Vipassanā School" approach to samatha and vipassanā developed by Mingun Sayadaw and U Nārada and popularized by Mahasi Sayadaw. Here samatha is considered an optional but not necessary component of the practice—vipassanā is possible without it. Another Burmese method popularized in the west, notably that of Pa-Auk sayadaw Bhaddanta Āciṇṇa, uphold the emphasis on samatha explicit in the commentarial tradition of the Visuddhimagga. Other Burmese traditions, derived from Ledi Sayadaw via Sayagyi U Ba Khin and popularized in the west by Mother Sayamagyi and S. N. Goenka, takes a similar approach. These Burmese traditions have been influential on Western Theravada-oriented teachers, notably Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg and Jack Kornfield.

There are also other less well known Burmese meditation methods, such as the system developed by U Vimala, which focuses on knowledge of dependent origination and cittanupassana (mindfulness of the mind).[97] Likewise, Sayadaw U Tejaniya's method also focuses on mindfulness of the mind.

Thai Forest tradition

[edit]Also influential is the Thai Forest Tradition deriving from Mun Bhuridatta and popularized by Ajahn Chah, which, in contrast, stresses the inseparability of the two practices, and the essential necessity of both practices. Other noted practitioners in this tradition include Ajahn Thate and Ajahn Maha Bua, among others.[98] There are other forms of Thai Buddhist meditation associated with particular teachers, including Buddhadasa Bhikkhu's presentation of anapanasati, Ajahn Lee's breath meditation method (which influenced his American student Thanissaro) and the "dynamic meditation" of Luangpor Teean Cittasubho.[99]

Other forms

[edit]There are other less mainstream forms of Theravada meditation practiced in Thailand which include the vijja dhammakaya meditation developed by Luang Pu Sodh Candasaro and the meditation of former supreme patriarch Suk Kai Thuean (1733–1822).[99] Newell notes that these two forms of modern Thai meditation share certain features in common with tantric practices such as the use of visualizations and centrality of maps of the body.[99]

A less common type of meditation is practiced in Cambodia and Laos by followers of Borān kammaṭṭhāna ('ancient practices') tradition. This form of meditation includes the use of mantras and visualizations.

Sarvāstivāda

[edit]The now defunct Sarvāstivāda tradition, and its related sub-schools like the Sautrāntika and the Vaibhāṣika, were the most influential Buddhists in North India and Central Asia. Their highly complex Abhidharma treatises, such as the Mahavibhasa, the Sravakabhumi and the Abhidharmakosha, contain new developments in meditative theory which had a major influence on meditation as practiced in East Asian Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhism. Individuals known as yogācāras (yoga practitioners) were influential in the development of Sarvāstivāda meditation praxis, and some modern scholars such as Yin Shun believe they were also influential in the development of Mahayana meditation.[100] The Dhyāna sutras (Chinese: 禪経) or "meditation summaries" (Chinese: 禪要) are a group of early Buddhist meditation texts which are mostly based on the Yogacara[note 23] meditation teachings of the Sarvāstivāda school of Kashmir circa 1st–4th centuries CE, which focus on the concrete details of the meditative practice of the Yogacarins of northern Gandhara and Kashmir.[1] Most of the texts only survive in Chinese and were key works in the development of the Buddhist meditation practices of Chinese Buddhism.

According to K.L. Dhammajoti, the Sarvāstivāda meditation practitioner begins with samatha meditations, divided into the fivefold mental stillings, each being recommended as useful for particular personality types:

- contemplation on the impure (asubhabhavana), for the greedy type person.

- meditation on loving kindness (maitri), for the hateful type

- contemplation on conditioned co-arising, for the deluded type

- contemplation on the division of the dhatus, for the conceited type

- mindfulness of breathing (anapanasmrti), for the distracted type.[101]

Contemplation of the impure, and mindfulness of breathing, was particularly important in this system; they were known as the 'gateways to immortality' (amrta-dvāra).[102] The Sarvāstivāda system practiced breath meditation using the same sixteen aspect model used in the anapanasati sutta, but also introduced a unique six aspect system which consists of:

- counting the breaths up to ten,

- following the breath as it enters through the nose throughout the body,

- fixing the mind on the breath,

- observing the breath at various locations,

- modifying is related to the practice of the four applications of mindfulness and

- purifying stage of the arising of insight.[103]

This sixfold breathing meditation method was influential in East Asia, and expanded upon by the Chinese Tiantai meditation master Zhiyi.[101]

After the practitioner has achieved tranquility, Sarvāstivāda Abhidharma then recommends one proceeds to practice the four applications of mindfulness (smrti-upasthāna) in two ways. First they contemplate each specific characteristic of the four applications of mindfulness, and then they contemplate all four collectively.[104]

In spite of this systematic division of samatha and vipasyana, the Sarvāstivāda Abhidharmikas held that the two practices are not mutually exclusive. The Mahavibhasa for example remarks that, regarding the six aspects of mindfulness of breathing, "there is no fixed rule here—all may come under samatha or all may come under vipasyana."[105] The Sarvāstivāda Abhidharmikas also held that attaining the dhyānas was necessary for the development of insight and wisdom.[105]

Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism

[edit]

Mahāyāna practice is centered on the path of the bodhisattva, a being which is aiming for full Buddhahood. Meditation (dhyāna) is one of the transcendent virtues (paramitas) which a bodhisattva must perfect in order to reach Buddhahood, and thus, it is central to Mahāyāna Buddhist praxis.

Indian Mahāyāna Buddhism was initially a network of loosely connected groups and associations, each drawing upon various Buddhist texts, doctrines and meditation methods.[106] Because of this, there is no single set of Indian Mahāyāna practices which can be said to apply to all Indian Mahāyānists, nor is there is a single set of texts which were used by all of them.

Textual evidence shows that many Mahāyāna Buddhists in northern India as well as in Central Asia practiced meditation in a similar way to that of the Sarvāstivāda school outlined above. This can be seen in what is probably the most comprehensive and largest Indian Mahāyāna treatise on meditation practice, the Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (compiled c. 4th century), a compendium which explains in detail Yogācāra meditation theory, and outlines numerous meditation methods as well as related advice.[107] Among the topics discussed are the various early Buddhist meditation topics such as the four dhyānas, the different kinds of samādhi, the development of insight (vipaśyanā) and tranquility (śamatha), the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthāna), the five hindrances (nivaraṇa), and classic Buddhist meditations such as the contemplation of unattractiveness (aśubhasaṃjnā), impermanence (anitya), suffering (duḥkha), and contemplation death (maraṇasaṃjñā).[108] Other works of the Yogācāra school, such as Asaṅga's Abhidharmasamuccaya, and Vasubandhu's Madhyāntavibhāga-bhāsya also discuss classic meditation topics such as mindfulness, smṛtyupasthāna, the 37 wings to awakening, and samadhi.[109] Some Mahāyāna sutras also teach early Buddhist meditation practices. For example, the Mahāratnakūṭa Sūtra and the Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra both teach the four foundations of mindfulness.[110]

In the Prajñāpāramitā literature

[edit]The Prajñāpāramitā Sutras are some of the earliest Mahāyāna sutras. Their teachings center on the bodhisattva path (viz. the paramitas), the most important of which is the perfection of transcendent knowledge or prajñāpāramitā. In the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras, prajñāpāramitā is described as a kind of samādhi (meditative absorption) which is also a deep understanding of reality arising from meditative insight that is totally non-conceptual and completely unattached to any person, thing or idea. The Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā, possibly the earliest of these texts, also equates prajñāpāramitā with what it terms the aniyato (unrestricted) samādhi, “the samādhi of not taking up (aparigṛhīta) any dharma”, and “the samādhi of not grasping at (anupādāna) any dharma” (as a self).[111] According to Shi Huifeng, this meditative concentration:

entails not only not clinging to the five aggregates as representative of all phenomena, but also not clinging to the very notion of the five aggregates, their existence or non-existence, their impermanence or eternality, their being dissatisfactory or satisfactory, their emptiness or self-hood, their generation or cessation, and so forth with other antithetical pairs. To so mistakenly perceive the aggregates is to “course in a sign” (nimite carati; xíng xiāng 行相), i.e. to engage in the signs and conceptualization of phenomena, and not to course in Prajñāpāramitā. Even to perceive of oneself as a bodhisattva who courses, or the Prajñāpāramitā in which one courses, are likewise coursing in signs.[112]

Prajñāpāramitā is closely associated with the practice of the three samādhis (trayaḥ samādhyaḥ): emptiness (śūnyatā), signlessness (animitta), and wishlessness or desirelessness (apraṇihita).[113] These three are found in early Buddhism as the three gates of liberation (triṇi vimokṣamukhāni). The Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā prajñāpāramitā describes these three contemplations as follows:

The focused state (sthiti) of mind examining all phenomena as being empty of individual characteristics is called the gate of liberation [through] emptiness, [or] the contemplation of emptiness. The focused state of mind examining all phenomena as being without [distinctive] signs [or: characteristics] is called the gate of liberation [through] signlessness, [or] the contemplation of signlessness. The focused state of mind examining all phenomena as being un[worthy of] desire [or: of directing one's attention to them] is called the gate of liberation [through] desirelessness, [or] the contemplation of desirelessness.[114]

These three samadhis are also described in the Mahāprajñāpāramitōpadeśa (Ch. Dà zhìdù lùn), chapter X.[115] Another key element of the practice of meditation in the Prajñāpāramitā texts is the fact that a bodhisattva must be careful while practicing these meditations to "not realize them" (na sākṣātkaroti), i.e. they must take care not to attain enlightenment prematurely and thus become an arhat.[116] This would entail a failure to stay on the bodhisattva path to full Buddhahood and to fall into the lesser vehicle (hinayana). To stay on the path of the bodhisattva while also practicing these powerful meditations, the bodhisattva must base themselves on universal friendliness (maitrī) directed towards all living beings and on bodhicitta (the intention to become a Buddha for the sake of all beings).[116] As the Aṣṭadaśasāhasrikā states

He does not cling to the disciples’ level or the level of Solitary Buddhas. On the contrary, it occurs to him, ‘Having intently practised the perfection of contemplation, my duty here [in this world] is to liberate all beings from the cycle of rebirths.’[116]

Innovative meditation methods

[edit]

Various Indian Mahāyāna texts show new innovative methods which were unique to Mahāyāna Buddhism. Texts such as the Pure Land sutras, the Akṣobhya-vyūha Sūtra and the Pratyutpanna Samādhi Sūtra teach meditations on a particular Buddha (such as Amitābha or Akshobhya). Through the repetition of their name or some other phrase and certain visualization methods, one is said to be able to meet a Buddha face to face or at least to be reborn in a Buddha field (also known as "Pure land") like Abhirati and Sukhavati after death.[117][118] The Pratyutpanna sutra for example, states that if one practices recollection of the Buddha (Buddhānusmṛti) by visualizing a Buddha in their Buddha field and developing this samadhi for some seven days, one may be able to meet this Buddha in a vision or a dream so as to learn the Dharma from them.[119] Alternatively, being reborn in one of their Buddha fields allows one to meet a Buddha and study directly with them, allowing one to reach Buddhahood faster. A set of sutras known as the Visualization Sutras also depict similar innovative practices using mental imagery. These practices been seen by some scholars as a possible explanation for the source of certain Mahāyāna sutras which are seen traditionally as direct visionary revelations from the Buddhas in their pure lands.[120]

Another popular Mahayana practice was the memorization and recitation of various texts, such as sutras, mantras and dharanis. According to Akira Hirakawa, the practice of reciting dharanis (chants or incantations) became very important in Indian Mahāyāna.[121] These chants were believed to have "the power to preserve good and prevent evil", as well as being useful to attain meditative concentration or samadhi.[113] Important Mahāyāna sutras such as the Lotus Sutra, Heart Sutra and others prominently include dharanis.[122][123] Ryûichi Abé states that dharanis are also prominent in the Prajñāpāramitā Sutras wherein the Buddha "praises dharani incantation, along with the cultivation of samadhi, as virtuous activity of a bodhisattva".[122] They are also listed in the Mahāprajñāpāramitōpadeśa, chapter X, as an important quality of a bodhisattva.[115]

Later Yogācāra sources also indicate that Mahayanists had begun to see their meditation methods as unique and different from Śrāvakayānist (i.e. non-Mahayana Buddhists) methods. For example, the Saṃdhinirmocanasūtra criticizes certain early Buddhist meditations as not suitable for Mahayanists, who instead focus their meditation on the true nature of things (suchness, tathatā).[124] The Āryasaṃdhinirmocanabhāṣya, a commentary attributed to Asaṅga, comments:

In the Śrāvakayāna, one thoroughly knows (*parijānāti) the Truth of Suffering, and so on [i.e. the other Truths], while in the Mahāyāna, one thoroughly knows [the Truths] through Suchness (*tathatā), etc.’[125]

According to Florin Delenau, "the text contrasts, I believe, the Śrāvakayānika analytical, highly reflective approach to the Mahāyānika synthetic, ultimately intuitive insight into the essence of the Reality. "[125]

A later Mahāyāna work which discusses meditation practice is Shantideva's Bodhicaryāvatāra (8th century) which depicts how a bodhisattva's meditation was understood in the later period of Indian Mahāyāna. Shantideva begins by stating that isolating the body and the mind from the world (i.e. from discursive thoughts) is necessary for the practice of meditation, which must begin with the practice of tranquility (śamatha).[126] He promotes classic practices like meditating on corpses and living in forests, but these are preliminary to the Mahāyāna practices which initially focus on generating bodhicitta, a mind intent on awakening for the benefit of all beings. An important of part of this practice is to cultivate and practice the understanding that oneself and other beings are actually the same, and thus all suffering must be removed, not just "mine". This meditation is termed by Shantideva "the exchange of self and other" and it is seen by him as the apex of meditation, since it simultaneously provides a basis for ethical action and cultivates insight into the nature of reality, i.e. emptiness.[126]

Another late Indian Mahāyāna meditation text is Kamalaśīla's Bhāvanākrama ("stages of meditation", 9th century), which teaches insight (vipaśyanā) and tranquility (śamatha) from a Yogācāra-Madhyamaka perspective.[127]

East Asian Mahāyāna

[edit]The meditation forms practiced during the initial stages of Chinese Buddhism did not differ much from those of Indian Mahayana Buddhism, though they did contain developments that could have arisen in Central Asia.

The works of the Chinese translator An Shigao (安世高, 147–168 CE) are some of the earliest meditation texts used by Chinese Buddhism and their focus is mindfulness of breathing (annabanna 安那般那). The Chinese translator and scholar Kumarajiva (344–413 CE) transmitted various meditation works, including a meditation treatise titled The Sūtra Concerned with Samādhi in Sitting Meditation (坐禅三昧经, T.614, K.991) which teaches the Sarvāstivāda system of fivefold mental stillings.[128] These texts are known as the Dhyāna sutras.[129] They reflect the meditation practices of Kashmiri Buddhists, influenced by Sarvāstivāda and Sautrantika meditation teachings, but also by Mahayana Buddhism.[130]

East Asian Yogācāra methods

[edit]The East Asian Yogācāra school or "Consciousness only school" (Ch. Wéishí-zōng), known in Japan as the Hossō school was a very influential tradition of Chinese Buddhism. They practiced several forms of meditation. According to Alan Sponberg, they included a class of visualization exercises, one of which centered on constructing a mental image of the Bodhisattva (and presumed future Buddha) Maitreya in Tusita heaven. A biography the Chinese Yogācāra master and translator Xuanzang depicts him practicing this kind of meditation. The goal of this practice seems to have been rebirth in Tusita heaven, so as to meet Maitreya and study Buddhism under him.[131]

Another method of meditation practiced in Chinese Yogācāra is called "the five level discernment of vijñapti-mātra" (impressions only), introduced by Xuanzang's disciple, Kuījī (632–682), which became one of the most important East Asian Yogācāra teachings.[132] According to Alan Sponberg, this kind of vipasyana meditation was an attempt "to penetrate the true nature of reality by understanding the three aspects of existence in five successive steps or stages". These progressive stages or ways of seeing (kuan) the world are:[133]

- "dismissing the false – preserving the real" (ch 'ien-hsu ts'un-shih)

- "relinquishing the diffuse – retaining the pure" (she-lan liu-ch 'un)

- "gathering in the extensions – returning to the source" (she-mo kuei-pen)

- "suppressing the subordinate – manifesting the superior" (yin-lueh hsien-sheng)

- "dismissing the phenomenal aspects – realizing the true nature" (ch 'ien-hsiang cheng-hsing)

Tiantai śamatha-vipaśyanā

[edit]In China it has been traditionally held that the meditation methods used by the Tiantai school are the most systematic and comprehensive of all.[134] In addition to its doctrinal basis in Indian Buddhist texts, the Tiantai school also emphasizes use of its own meditation texts which emphasize the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Of these texts, Zhiyi's Concise Śamathavipaśyanā (小止観), Mohe Zhiguan (摩訶止観, Sanskrit Mahāśamathavipaśyanā), and Six Subtle Dharma Gates (六妙法門) are the most widely read in China.[134] Rujun Wu identifies the work Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā of Zhiyi as the seminal meditation text of the Tiantai school.[135] Regarding the functions of śamatha and vipaśyanā in meditation, Zhiyi writes in his work Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā:

The attainment of Nirvāṇa is realizable by many methods whose essentials do not go beyond the practice of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Śamatha is the first step to untie all bonds and vipaśyanā is essential to root out delusion. Śamatha provides nourishment for the preservation of the knowing mind, and vipaśyanā is the skillful art of promoting spiritual understanding. Śamatha is the unsurpassed cause of samādhi, while vipaśyanā begets wisdom.[136]

The Tiantai school also places a great emphasis on ānāpānasmṛti, or mindfulness of breathing, in accordance with the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Zhiyi classifies breathing into four main categories: panting (喘), unhurried breathing (風), deep and quiet breathing (氣), and stillness or rest (息). Zhiyi holds that the first three kinds of breathing are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the breathing should reach stillness and rest.[137] Zhiyi also outlines four kinds of samadhi in his Mohe Zhiguan, and ten modes of practicing vipaśyanā.

Esoteric practices in Japanese Tendai

[edit]One of the adaptations by the Japanese Tendai school was the introduction of Mikkyō (esoteric practices) into Tendai Buddhism, which was later named Taimitsu by Ennin. Eventually, according to Tendai Taimitsu doctrine, the esoteric rituals came to be considered of equal importance with the exoteric teachings of the Lotus Sutra. Therefore, by chanting mantras, maintaining mudras, or performing certain meditations, one is able to see that the sense experiences are the teachings of Buddha, have faith that one is inherently an enlightened being, and one can attain enlightenment within this very body. The origins of Taimitsu are found in China, similar to the lineage that Kūkai encountered in his visit to Tang China and Saichō's disciples were encouraged to study under Kūkai.[138]

Huayan meditation theory

[edit]The Huayan school was a major school of Chinese Buddhism, which also strongly influenced Chan Buddhism. An important element of their meditation theory and practice is what was called the "Fourfold Dharmadhatu" (sifajie, 四法界).[139] Dharmadhatu (法界) is the goal of the bodhisattva's practice, the ultimate nature of reality or deepest truth which must be known and realized through meditation. According to Fox, the Fourfold Dharmadhatu is "four cognitive approaches to the world, four ways of apprehending reality". Huayan meditation is meant to progressively ascend through these four "increasingly more holographic perspectives on a single phenomenological manifold."

These four ways of seeing or knowing reality are:[139]

- All dharmas are seen as particular separate events or phenomena (shi 事). This is the mundane way of seeing.

- All events are an expression of li (理, the absolute, principle or noumenon), which is associated with the concepts of shunyata, "One Mind" (yi xin 一心) and Buddha nature. This level of understanding or perspective on reality is associated with the meditation on "true emptiness".

- Shi and Li interpenetrate (lishi wuai 理事無礙), this is illuminated by the meditation on the "non-obstruction of principle and phenomena."

- All events interpenetrate (shishi wuai 事事無礙), "all distinct phenomenal dharmas interfuse and penetrate in all ways" (Zongmi). This is seen through the meditation on "universal pervasion and complete accommodation."

According to Paul Williams, the reading and recitation of the Avatamsaka sutra was also a central practice for the tradition, for monks and laity.[140]

Pure land Buddhism

[edit]

In Pure Land Buddhism, repeating the name of Amitābha is traditionally a form of mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti). This term was translated into Chinese as nianfo (Chinese: 念佛), by which it is popularly known in English. The practice is described as calling the buddha to mind by repeating his name, to enable the practitioner to bring all his or her attention upon that Buddha (samādhi).[141] This may be done vocally or mentally, and with or without the use of Buddhist prayer beads. Those who practice this method often commit to a fixed set of repetitions per day, often from 50,000 to over 500,000.[141]

Another common Pure Land practice is that of Buddha contemplation (guanfo), which relies on the visualization of various mental images, such as Buddha Amitābha, his attendant bodhisattvas, or the features of the Pure Land.[142] The basis of this meditation is found in the Amitāyus Contemplation Sūtra.[143]

Repeating the Pure Land Rebirth dhāraṇī is another method in Pure Land Buddhism. Similar to the mindfulness practice of repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha, this dhāraṇī is another method of meditation and recitation in Pure Land Buddhism. The repetition of this dhāraṇī is said to be very popular among traditional Chinese Buddhists.[144]

Chán

[edit]

During sitting meditation, referred to as zazen, (坐禅, Chinese: zuòchán; Japanese: zazen; Korean: jwaseon), practitioners usually assume a position such as the lotus position, half-lotus, Burmese, or seiza, often using the dhyāna mudrā. Often, a square or round cushion placed on a padded mat is used to sit on; in some other cases, a chair may be used. Various techniques and meditation forms are used in the different Zen traditions. Mindfulness of breathing is a common practice, used to develop mental focus and concentration.[145]

Another common form of sitting meditation is called "silent illumination" (Chinese: mòzhào; Japanese: mokushō). This practice was traditionally promoted by the Caodong school of Chinese Chan and is associated with Hongzhi Zhengjue (1091—1157).[146] In Hongzhi's practice of "nondual objectless meditation" the mediator strives to be aware of the totality of phenomena instead of focusing on a single object, without any interference, conceptualizing, grasping, goal seeking, or subject-object duality.[147] This practice is also popular in the major schools of Japanese Zen, but especially Sōtō, where it is more widely known as Shikantaza (Ch. zhǐguǎn dǎzuò, "Just sitting").

During the Sòng dynasty, a new meditation method was popularized by figures such as Dahui, which was called kanhua chan ("observing the phrase" meditation) which referred to contemplation on a single word or phrase (called the huatou, "critical phrase") of a gōng'àn (kōan).[148] In Chinese Chan and Korean Seon, this practice of "observing the huatou" (hwadu in Korean) is a widely practiced method.[149]

In the Japanese Rinzai school, kōan introspection developed its own formalized style, with a standardized curriculum of kōans which must be studies and "passed" in sequence. This process includes standardized questions and answers during a private interview with one's Zen teacher.[150] Kōan-inquiry may be practiced during zazen (sitting meditation), kinhin (walking meditation), and throughout all the activities of daily life. The goal of the practice is often termed kensho (seeing one's true nature). Kōan practice is particularly emphasized in Rinzai, but it also occurs in other schools or branches of Zen depending on the teaching line.[151]

Tantric Buddhism

[edit]

Tantric Buddhism (Esoteric Buddhism or Mantrayana) refers to various traditions which developed in India from the fifth century onwards and then spread to the Himalayan regions and East Asia. In the Tibetan tradition, it is also known as Vajrayāna, while in China it is known as Zhenyan (Ch: 真言, "true word", "mantra"), as well as Mìjiao (Esoteric Teaching), Mìzōng ("Esoteric Tradition") or Tángmì ("Tang Esoterica"). Tantric Buddhism generally includes all of the traditional forms of Mahayana meditation, but its focus is on several unique and special forms of "tantric" or "esoteric" meditation practices, which are seen as faster and more efficacious. These Tantric Buddhist forms are derived from texts called the Buddhist Tantras. To practice these advanced techniques, one is generally required to be initiated into the practice by an esoteric master (Sanskrit: acarya) or guru (Tib. lama) in a ritual consecration called abhiseka (Tib. wang).

In Tibetan Buddhism, the central defining form of Vajrayana meditation is Deity Yoga (devatayoga).[152] This involves the recitation of mantras, prayers and visualization of the yidam or deity (usually the form of a Buddha or a bodhisattva) along with the associated mandala of the deity's Pure Land.[153] Advanced Deity Yoga involves imagining yourself as the deity and developing "divine pride", the understanding that oneself and the deity are not separate. "Yidam" in Tibetan technically means "tight mind" which suggests that the use of a deity as an object of meditation is intended to create total absorption into the meditative experience. Yidam practice focuses on three essential aspects of deities which, in turn, are the three principal aspects of all being: body, speech and mind. Practitioners meditate on the body of the deity, usually visually themselves becoming that body. Chanting mantra becomes the manifestation of enlightened speech with the meditation ultimately aspiring to become Buddha mind. Most tantric practices incorporate these three aspects sequentially or simultaneously. Deity practice should be differentiated from worship of gods in other religions. One way of describing tantric practice is to understand it as a "strong method" for developing an awareness of the true nature of consciousness.

Other forms of meditation in Tibetan Buddhism include the Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings, each taught by the Kagyu and Nyingma lineages of Tibetan Buddhism respectively. The goal of these is to familiarize oneself with the ultimate nature of mind which underlies all existence, the Dharmakāya. There are also other practices such as Dream Yoga, Tummo, the yoga of the intermediate state (at death) or bardo, sexual yoga and chöd. The shared preliminary practices of Tibetan Buddhism are called ngöndro, which involves visualization, mantra recitation, and many prostrations.

Chinese esoteric Buddhism focused on a separate set of tantras than Tibetan Buddhism (such as the Mahavairocana Tantra and Vajrasekhara Sutra), and thus their practices are drawn from these different sources, though they revolve around similar techniques such as visualization of mandalas, mantra recitation and use of mudras. This also applies for the Japanese Shingon school and the Tendai school (which, though derived from the Tiantai school, also adopted esoteric practices). In the East Asian tradition of esoteric praxis, the use of mudra, mantra and mandala are regarded as the "three modes of action" associated with the "Three Mysteries" (sanmi 三密) are seen as the hallmarks of esoteric Buddhism.[154]

Therapeutic uses of meditation

[edit]Meditation based on Buddhist meditation principles has been practiced by people for a long time for the purposes of effecting mundane and worldly benefit.[155] Mindfulness and other Buddhist meditation techniques have been advocated in the West by psychologists and expert Buddhist meditation teachers such as Dipa Ma, Anagarika Munindra, Thích Nhất Hạnh, Pema Chödrön, Clive Sherlock, Mother Sayamagyi, S. N. Goenka, Jon Kabat-Zinn, Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, Tara Brach, Alan Clements, and Sharon Salzberg, who have been widely attributed with playing a significant role in integrating the healing aspects of Buddhist meditation practices with the concept of psychological awareness, healing, and well-being. Although mindfulness meditation[156] has received the most research attention, loving kindness[157] (metta) and equanimity (upekkha) meditation are beginning to be used in a wide array of research in the fields of psychology and neuroscience.[citation needed]

The accounts of meditative states in the Buddhist texts are in some regards free of dogma, so much so that the Buddhist scheme has been adopted by Western psychologists attempting to describe the phenomenon of meditation in general.[note 24] However, it is exceedingly common to encounter the Buddha describing meditative states involving the attainment of such magical powers (Sanskrit ṛddhi, Pali iddhi) as the ability to multiply one's body into many and into one again, appear and vanish at will, pass through solid objects as if space, rise and sink in the ground as if in water, walking on water as if land, fly through the skies, touching anything at any distance (even the moon or sun), and travel to other worlds (like the world of Brahma) with or without the body, among other things,[158][159][160] and for this reason the whole of the Buddhist tradition may not be adaptable to a secular context, unless these magical powers are seen as metaphorical representations of powerful internal states that conceptual descriptions could not do justice to.

Key terms

[edit]| English | Pali | Sanskrit | Chinese | Tibetan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mindfulness/awareness | sati | smṛti | 念 (niàn) | དྲན་པ། (wylie: dran pa) |

| clear comprehension | sampajañña | samprajaña | 正知力 (zhèng zhī lì) | ཤེས་བཞིན། shezhin (shes bzhin) |

| vigilance/heedfulness | appamada | apramāda | 不放逸座 (bù fàng yì zuò) | བག་ཡོད། bakyö (bag yod) |

| ardency | atappa | ātapaḥ | 勇猛 (yǒng měng) | nyima (nyi ma) |

| attention/engagement | manasikara | manaskāraḥ | 如理作意 (rú lǐ zuò yì) | ཡིད་ལ་བྱེད་པ། yila jepa (yid la byed pa) |

| foundation of mindfulness | satipaṭṭhāna | smṛtyupasthāna | 念住 (niànzhù) | དྲན་པ་ཉེ་བར་བཞག་པ། trenpa neybar zhagpa (dran pa nye bar gzhag pa) |

| mindfulness of breathing | ānāpānasati | ānāpānasmṛti | 安那般那 (ānnàbānnà) | དབུགས་དྲན་པ། wūk trenpa (dbugs dran pa) |

| calm abiding/cessation | samatha | śamatha | 止 (zhǐ) | ཞི་གནས། shiney (zhi gnas) |

| insight/contemplation | vipassanā | vipaśyanā | 観 (guān) | ལྷག་མཐོང་། (lhag mthong) |

| meditative concentration | samādhi | samādhi | 三昧 (sānmèi) | ཏིང་ངེ་འཛིན། ting-nge-dzin (ting nge dzin) |

| meditative absorption | jhāna | dhyāna | 禪 (chán) | བསམ་གཏན། samten (bsam gtan) |

| cultivation | bhāvanā | bhāvanā | 修行 (xiūxíng) | སྒོམ་པ། (sgom pa) |

| cultivation of analysis | vitakka and vicāra | *vicāra-bhāvanā | 尋伺察 (xún sì chá) | དཔྱད་སྒོམ། (dpyad sgom) |

| cultivation of settling | — | *sthāpya-bhāvanā | — | འཇོག་སྒོམ། jokgom ('jog sgom) |

See also

[edit]- General Buddhist practices

- Mindfulness – awareness in the present moment

- Satipatthana - Four Foundations of Mindfulness, based on Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta

- Anapanasati – focusing on the breath, reference to Ānāpānasati Sutta

- Theravada Buddhist meditation practices

- Samatha – calm-abiding, which steadies, composes, unifies and concentrates the mind

- Vipassanā – insight, which enables one to see, explore and discern "formations" (conditioned phenomena based on the five aggregates)

- Satipatthana – Mindfulness of body, sensations, mind and mental phenomena

- Brahmavihara – including loving-kindness (Metta), compassion (Karuṇā), sympathetic joy (Mudita) and equanimity (Upekkha)

- Buddhānussati – meditation on the nine Noble Qualities of Lord Buddha

- Patikkulamanasikara

- Kammaṭṭhāna

- Mahasati Meditation

- Dhammakaya Meditation

- Zen Buddhist meditation practices

- Shikantaza – just sitting

- Kinhin

- Zazen

- Koan

- Hua Tou

- Suizen (historically practiced by the Fuke sect)

- Vajrayana and Tibetan Buddhist meditation practices

- Deity yoga

- Ngondro – preliminary practices

- Tonglen – giving and receiving

- Phowa – transference of consciousness at the time of death

- Chöd – cutting through fear by confronting it

- Mahamudra – the Kagyu version of 'entering the all-pervading Dharmadatu', the 'nondual state', or the 'absorption state'

- Dzogchen – the natural state, the Nyingma version of Mahamudra

- Tantra techniques

- Proper floor-sitting postures and supports while meditating

- Floor sitting: cross-legged (full lotus, half lotus, Burmese) or seiza

- Cushions: zafu, zabuton

- Traditional Buddhist texts on meditation

- Anapanasati Sutta (in the Pali Nikayas) and parallels in the Āgamas (Ānāpānasmṛti Sūtra)

- Satipatthana Sutta (in the Pali Nikayas) and its parallel in the Āgamas (Smṛtyupasthāna Sūtra)

- Upajjhatthana Sutta (in the Pali Nikayas)

- Kāyagatāsati Sutta (in the Pali Nikayas)

- Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga ('The path of Purification'), used in Theravada Buddhism

- Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (Treatise on the Stages of Yoga), a classic north Indian compendium on meditation used by the Indian Yogācāra school, remains influential in East Asian Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism used in Tibetan Buddhism

- Zhiyi's Great Concentration and Insight (Mohe Zhiguan) – used in the Chinese Tiantai school

- Seventeen tantras – Major Tibetan Dzogchen texts.

- The Wangchuk Dorje's "Ocean of Definitive Meaning", major text on Tibetan Mahamudra meditation in the Kagyu school.

- Dakpo Tashi Namgyal's "Mahamudra: The Moonlight – Quintessence of Mind and Meditation"

- Fukan-zazengi (Advice on Zazen) – By Dogen, used in the Japanese Soto Zen school.

- Traditional preliminary practices to Buddhist meditation

- Taking refuge in the Triple Gem

- Five Precepts

- Eight Precepts

- Awgatha

- Gadaw

- prostrations (also see Ngondro)

- Western mindfulness

- Mindfulness (psychology) – Western applications of Buddhist ideas

- Analog in Vedas

- Analog in Taoism

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The Pali and Sanskrit word bhāvanā literally means "development" as in "mental development." For the association of this term with "meditation," see Epstein (1995), p. 105; and, Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 20. As an example from a well-known discourse of the Pāli Canon, in "The Greater Exhortation to Rahula" (Maha-Rahulovada Sutta, MN 62), Sariputta tells Rahula (in Pali, based on VRI, n.d.): ānāp ānassatiṃ, rāhula, bhāvanaṃ bhāvehi. Thanissaro (2006) translates this as: "Rahula, develop the meditation [bhāvana] of mindfulness of in-&-out breathing." (Square-bracketed Pali word included based on Thanissaro, 2006, end note.)

- ^ a b See, for example, Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), entry for "jhāna1"; Thanissaro (1997); as well as, Kapleau (1989), p. 385, for the derivation of the word "zen" from Sanskrit "dhyāna." PTS Secretary Dr. Rupert Gethin, in describing the activities of wandering ascetics contemporaneous with the Buddha, wrote:

[T]here is the cultivation of meditative and contemplative techniques aimed at producing what might, for the lack of a suitable technical term in English, be referred to as 'altered states of consciousness'. In the technical vocabulary of Indian religious texts, such states come to be termed 'meditations' (Sanskrit: dhyāna, Pali: jhāna) or 'concentrations' (samādhi); the attainment of such states of consciousness was generally regarded as bringing the practitioner to deeper knowledge and experience of the nature of the world." (Gethin, 1998, p. 10.)

- ^ * Kamalashila (2003), p. 4, states that Buddhist meditation "includes any method of meditation that has awakening as its ultimate aim."

* Bodhi (1999): "To arrive at the experiential realization of the truths it is necessary to take up the practice of meditation [...] At the climax of such contemplation the mental eye [...] shifts its focus to the unconditioned state, Nibbana."

* Fischer-Schreiber et al. (1991), p. 142: "Meditation – general term for a multitude of religious practices, often quite different in method, but all having the same goal: to bring the consciousness of the practitioner to a state in which he can come to an experience of 'awakening,' 'liberation,' 'enlightenment.'"

* Kamalashila (2003) further allows that some Buddhist meditations are "of a more preparatory nature" (p. 4). - ^ Goldstein (2003) writes that, in regard to the Satipatthana Sutta, "there are more than fifty different practices outlined in this Sutta. The meditations that derive from these foundations of mindfulness are called vipassana [...] and in one form or another – and by whatever name – are found in all the major Buddhist traditions." (p. 92)

The forty concentrative meditation subjects refer to Visuddhimagga's oft-referenced enumeration. - ^ Regarding Tibetan visualizations, Kamalashila (2003), writes: "The Tara meditation [...] is one example out of thousands of subjects for visualization meditation, each one arising out of some meditator's visionary experience of enlightened qualities, seen in the form of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas." (p. 227)

- ^ Polak refers to Vetter, who noted that in the suttas right effort leads to a calm state of mind. When this calm and self-restraint had been reached, the Buddha is described as sitting down and attaining the first jhana, in an almost natural way.[15]

- ^ Kuan refers to Bronkhorst (1985), Dharma and Abhidharma, p.312-314.

- ^ Kuan refers to Sujato (2006), A history of mindfulness: how insight worsted tranquility in the Satipatthana Sutta, p.264-273

- ^ Keren Arbel refers to Majjhima Nikaya 26, Ariyapariyesana Sutta, The Noble Search

See also:

* Majjhima Nikaya 111, Anuppada Sutta

* AN 05.028, Samadhanga Sutta: The Factors of Concentration.

See Johansson (1981), Pali Buddhist texts Explained to Beginners for a word-by-word translation. - ^ Arbel explains that "viveka" is usually translated as "detachment," "separation," or "seclusion," but the primary meaning is "discrimination." According to Arbel, the usage of vivicca/vivicceva and viveka in the description of the first dhyana "plays with both meanings of the verb; namely, its meaning as discernment and the consequent 'seclusion' and letting go," in line with the "discernment of the nature of experience" developed by the four satipatthanas.[31] Compare Dogen: "Being apart from all disturbances and dwelling alone in a quiet place is called "enjoying serenity and tranquility.""[32]

Arbel further argues that viveka resembles dhamma vicaya, which is mentioned in the bojjhanga, an alternative description of the dhyanas, but the only bojjhanga-term not mentioned in the stock dhyana-description.[33] Compare Sutta Nipatha 5.14 Udayamāṇavapucchā (The Questions of Udaya): "Pure equanimity and mindfulness, preceded by investigation of principles—this, I declare, is liberation by enlightenment, the smashing of ignorance.” (Translation: Sujato) - ^ Stta Nipatha 5:13 Udaya’s Questions (transl. Thanissaro): "With delight the world’s fettered. With directed thought it’s examined."

Chen 2017: "Samadhi with general examination and specific in-depth investigation means getting rid of the not virtuous dharmas, such as greedy desire and hatred, to stay in joy and pleasure caused by nonarising, and to enter the first meditation and fully dwell in it."

Arbel 2016, p. 73: "Thus, my suggestion is that we should interpret the existence of vitakka and vicara in the first jhana as wholesome 'residues' of a previous development of wholesome thoughts. They denote the 'echo' of these wholesome thoughts, which reverberates in one who enters the first jhana as wholesome attitudes toward what is experienced." - ^ In the Pali canon, Vitakka-vicāra form one expression, which refers to directing one's thought or attention on an object (vitarka) and investigate it (vicāra).[36][39][40][41][42] According to Dan Lusthaus, vitarka-vicāra is analytic scrutiny, a form of prajna. It "involves focusing on [something] and then breaking it down into its functional components" to understand it, "distinguishing the multitude of conditioning factors implicated in a phenomenal event."[43] The Theravada commentarial tradition, as represented by Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga, interprets vitarka and vicāra as the initial and sustained application of attention to a meditational object, which culminates in the stilling of the mind when moving on to the second dhyana.[44][45] According to Fox and Bucknell it may also refer to "the normal process of discursive thought," which is quieted through absorption in the second jhāna.[45][44]

- ^ The standard translation for samadhi is "concentration"; yet, this translation/interpretation is based on commentarial interpretations, as explained by a number of contemporary authors.[5] Tilmann Vetter notes that samadhi has a broad range of meanings, and "concentration" is just one of them. Vetter argues that the second, third and fourth dhyana are samma-samadhi, "right samadhi," building on a "spontaneous awareness" (sati) and equanimity which is perfected in the fourth dhyana.[48]

- ^ The common translation, based on the commentarial interpretation of dhyana as expanding states of absorption, translates sampasadana as "internal assurance." Yet, as Bucknell explains, it also means "tranquilizing," which is more apt in this context.[44] See also Passaddhi.

- ^ Upekkhā is one of the Brahmaviharas.

- ^ With the fourth jhāna comes the attainment of higher knowledge (abhijñā), that is, the extinction of all mental intoxicants (āsava), but also psychic powers.[55] For instance in AN 5.28, the Buddha states (Thanissaro, 1997.):

"When a monk has developed and pursued the five-factored noble right concentration in this way, then whichever of the six higher knowledges he turns his mind to know and realize, he can witness them for himself whenever there is an opening...."

"If he wants, he wields manifold supranormal powers. Having been one he becomes many; having been many he becomes one. He appears. He vanishes. He goes unimpeded through walls, ramparts, and mountains as if through space. He dives in and out of the earth as if it were water. He walks on water without sinking as if it were dry land. Sitting crosslegged he flies through the air like a winged bird. With his hand he touches and strokes even the sun and moon, so mighty and powerful. He exercises influence with his body even as far as the Brahma worlds. He can witness this for himself whenever there is an opening ..." - ^ Gombrich: "I know this is controversial, but it seems to me that the third and fourth jhanas are thus quite unlike the second."[56]

- ^ Wynne: "Thus the expression sato sampajāno in the third jhāna must denote a state of awareness different from the meditative absorption of the second jhāna (cetaso ekodibhāva). It suggests that the subject is doing something different from remaining in a meditative state, i.e., that he has come out of his absorption and is now once again aware of objects. The same is true of the word upek(k)hā: it does not denote an abstract 'equanimity', [but] it means to be aware of something and indifferent to it [...] The third and fourth jhāna-s, as it seems to me, describe the process of directing states of meditative absorption towards the mindful awareness of objects.[59]

- ^ According to Gombrich, "the later tradition has falsified the jhana by classifying them as the quintessence of the concentrated, calming kind of meditation, ignoring the other - and indeed higher - element.[56]

- ^ These definitions of samatha and vipassana are based on the "Four Kinds of Persons Sutta" (AN 4.94). This article's text is primarily based on Bodhi (2005), pp. 269-70, 440 n. 13. See also Thanissaro (1998d).

- ^ Bodhi (2000), pp. 1251-53. See also Thanissaro (1998c) (where this sutta is identified as SN 35.204). See also, for instance, a discourse (Pali: sutta) entitled, "Serenity and Insight" (SN 43.2), where the Buddha states: "And what, bhikkhus, is the path leading to the unconditioned? Serenity and insight...." (Bodhi, 2000, pp. 1372-73).

- ^ See Thanissaro (1997) where for instance he underlines: "When [the Pali discourses] depict the Buddha telling his disciples to go meditate, they never quote him as saying 'go do vipassana,' but always 'go do jhana.' And they never equate the word vipassana with any mindfulness techniques. In the few instances where they do mention vipassana, they almost always pair it with samatha – not as two alternative methods, but as two qualities of mind that a person may 'gain' or 'be endowed with,' and that should be developed together."

Similarly, referencing MN 151, vv. 13–19, and AN IV, 125-27, Ajahn Brahm (who, like Bhikkhu Thanissaro, is of the Thai Forest Tradition) writes: "Some traditions speak of two types of meditation, insight meditation (vipassana) and calm meditation (samatha). In fact, the two are indivisible facets of the same process. Calm is the peaceful happiness born of meditation; insight is the clear understanding born of the same meditation. Calm leads to insight and insight leads to calm." (Brahm, 2006, p. 25.) - ^ To be distinguished from the Mahayana Yogacara school, though they may have been a precursor.[1]

- ^ Michael Carrithers, The Buddha, 1983, pages 33-34. Found in Founders of Faith, Oxford University Press, 1986. The author is referring to Pali literature. See however B. Alan Wallace, The bridge of quiescence: experiencing Tibetan Buddhist meditation. Carus Publishing Company, 1998, where the author demonstrates similar approaches to analyzing meditation within the Indo-Tibetan and Theravada traditions.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Deleanu, Florin (1992); Mindfulness of Breathing in the Dhyāna Sūtras. Transactions of the International Conference of Orientalists in Japan (TICOJ) 37, 42-57.

- ^ a b c d Vetter 1988.

- ^ a b c d e f Bronkhorst (1993).