Moses the Black

Moses the Ethiopian | |

|---|---|

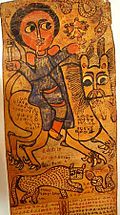

Icon of St. Moses | |

| Desert Father Hieromonk and Hieromartyr | |

| Born | 330 AD Ethiopia[1] |

| Died | 405 AD Scetis, Egypt |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodoxy Catholic Church Anglican Communion Lutheranism |

| Major shrine | Paromeos Monastery, Scetis, Egypt |

| Feast | August 28 (Chalcedonian) July 1—Paoni 24 (Oriental) July 2 (Episcopal Church)[2] |

| Patronage | Africa, nonviolence |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

Moses the Black (Greek: Μωϋσῆς ὁ Αἰθίοψ, romanized: Mōüsês ho Aithíops, Arabic: موسى, Coptic: Ⲙⲟⲥⲉⲥ; 330 – 405), also known as Moses the Strong, Moses the Robber, and Moses the Ethiopian, was an ascetic hieromonk in Egypt in the fourth century AD, and a Desert Father. He is highly venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox Church. According to stories about him, he converted from a life of crime to one of asceticism. He is mentioned in Sozomen's Ecclesiastical History, written about 70 years after Moses's death.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Moses was a slave of a government official in Egypt until he was dismissed for theft and suspected murder. He then roamed the Nile Valley with an infamous and violent gang of 75 robbers.[3] Moses was a man of huge physical stature, strength and courage, and became leader of this gang of robbers that became a social menace and living terror to the communities where they roamed.[4]

Conversion to Christianity

[edit]On one occasion, a barking dog prevented Moses from carrying out a robbery, so he swore vengeance on the owner. In a second attempt, with a sword in his mouth, Moses swam across the Nile towards the owner's hut. The owner, again alerted, was able to hide, and the frustrated Moses stole four of his sheep and took them to slaughter, selling their fleece in exchange for wine.[5][6] Attempting to hide from local authorities, he took shelter with some monks in a colony in the desert of Wadi El Natrun, then called Scetis, near Alexandria. The dedication of their lives, as well as their peace and contentment, influenced Moses deeply. He soon gave up his old way of life, became a Christian, was baptized and joined the monastic community at Scetis.[4]

Monastic life

[edit]Moses had a rather difficult time adjusting to regular monastic discipline. His flair for adventure remained with him. Attacked by a group of robbers in his desert cell, Moses fought back, overpowered the intruders, and dragged them to the chapel where the other monks were at prayer. He told the brothers that he did not think it was Christian to hurt the robbers and asked what he should do with them. The robbers themselves repented and joined the community as brothers afterwards. Moses was zealous in all he did, but became discouraged when he concluded he was not perfect enough. Feeling overcome by despair and once again tempted by his former passions, early one morning, Isidore, abbot of the monastery, took Moses to the roof. Together they watched the first rays of dawn come over the horizon, and Isidore said to Moses, "Only slowly do the rays of the sun drive away the night and usher in a new day, and thus, only slowly does one become a perfect contemplative.[3][5]

Moses proved to be effective as a prophetic spiritual leader. The abbot ordered the brothers to fast during a particular week. Some brothers came to Moses, and he prepared a meal for them. Neighboring monks reported to the abbot that Moses was breaking the fast. When they came to confront Moses, they changed their minds, saying, "You did not keep a human commandment, but it was so that you might keep the divine commandment of hospitality." Some see in this account one of the earliest allusions to the Paschal fast, which developed at this time.

When a brother committed a fault and Moses was invited to a meeting to discuss an appropriate penance, Moses refused to attend. When he was again called to the meeting, Moses took a leaking jug filled with water and carried it on his shoulder. Another version of the story has him carrying a basket filled with sand. When he arrived at the meeting place, the others asked why he was carrying the jug. He replied, "My sins run out behind me and I do not see them, but today I am coming to judge the errors of another." On hearing this, the assembled brothers forgave the erring monk.[4]

Moses became the spiritual leader of a colony of hermits in the Western Desert. Later, he was ordained a priest.[3]

Death

[edit]At about age 75, about the year 405 AD, word came that the Mazices, a group of Berbers, planned to attack the monastery. The brothers wanted to defend themselves, but Moses forbade it. He told them to retreat, rather than take up weapons. Citing that a violent death was the appropriate death for a former robber—"All who take the sword will perish by the sword"—he opted to remain behind. He was joined by seven others, and they were together martyred by the bandits on 24 Paoni (July 1).[4][7]

A different story of Abba Moses' death is related in The Paradise of the Holy Fathers:

31. Abba Poemen said: Abba Moses asked Abba Zechariah a question when he was about to die, and said unto him, "Father, is it good that we should hold our peace?" And Zechariah said unto him, "Yea, my son, hold thy peace." And at the time of his death, whilst Abba Isidore was sitting with him, Abba Moses looked up to heaven, and said, "Rejoice and be glad, O my son Zechariah, for the gates of heaven have been opened."[8]

Legacy

[edit]Moses was highly praised by his contemporaries. In his 5th century AD Ecclesiastical History, written about 70 years after Moses's death, Hermias Sozomen sums up Moses's legacy as follows:

So sudden a conversion from vice to virtue was never before witnessed, nor such rapid attainments in monastical philosophy. Hence God rendered him an object of dread to the demons and he was ordained presbyter over the monks at Scetis. After a life spent in this manner, he died at the age of seventy-five, leaving behind him numerous eminent disciples.[9]

— Sozomen, in his Ecclesiastical History, Book VI, Chapter XXIX

A modern interpretation honors Moses the Ethiopian as an apostle of non-violence. His relics and major shrine are found today at the Church of the Virgin Mary in the Paromeos Monastery, a Coptic Orthodox monastery located in Wadi El Natrun in Egypt.[10]

He was a spiritual guide to many a young monk and to many Christians over the generations. Some of his well-known teachings include:

"Do no harm to anyone; do not think anything bad in your heart towards anyone; do not scorn the man who does evil, do not put confidence in him who does wrong to his neighbor; do not rejoice with him who injures his neighbor. This is what dying to one’s neighbor means."[10]

“When someone is occupied with his own faults, he does not see those of neighbor.”[10]

"If a man’s deeds are not in harmony with his prayer, he labors in vain.”

See also

[edit]- Paromeos Monastery

- Or of Nitria

- Scetis

- Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria

- Coptic Catholic Church

- Monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian

- Black people in ancient Roman history

Citations

[edit]- ^ "Venerable Moses the Black of Scete", Orthodox Church in America

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 2019-12-17. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ a b c "History of St. Moses the Black Priory". Stmosestheblackpriory.org. Archived from the original on 2011-08-29. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ^ a b c d "Moses the Black: From Sinner to Ascetic". Again. Conciliar Press. June 1994. pp. 28, 30. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ a b FELICITY, SISTER (1964). "St Moses the Black". Life of the Spirit (1946-1964). 19 (214): 36–38. doi:10.1017/S0269359300000069. ISSN 0269-3593. JSTOR 43706454.

- ^ Wortley, John (1996). "DE LATRONE CONVERSO : THE TALE OF THE CONVERTED ROBBER (BHG 1450kb W861)". Byzantion. 66 (1): 219–243. ISSN 0378-2506. JSTOR 44172454.

- ^ Ward, B. (1984). The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: The Alphabetical Collection (revised ed.). Liturgical Press: Collegeville, MN.

- ^ The Paradise Or Garden of the Holy Fathers: Being Histories of the ... - Saint Athanasius (Patriarch of Alexandria) - Google Boeken. 1907. Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ^ Sozomen, Hermias (2018). The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen. Merchantville, New Jersey: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 978-1-935228-15-8.

- ^ a b c Abdelsayed, Fr. John Paul (2010). The Strong Saint Abba Moses. Saint Paul Brotherhood Press. ISBN 978-0-9721698-3-7.

Primary sources

[edit]- Palladius (1918). The Lausiac History. London: The Macmillan Company.

- Sozomen, Hermias (2018). The Ecclesiastical History of Sozomen. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing. ISBN 978-1-935228-15-8.