Types of cheese

There are many different types of cheese, which can be grouped or classified according to criteria such as: length of fermentation, texture, production method, fat content, animal source of the milk, and country or region of origin. These criteria may be used either singly or in combination,[1] with no method used universally.[2] The most common traditional categorization is based on moisture content, which is then further narrowed down by fat content and curing or ripening methods.[3][4]

The combination of types produces around 51 different varieties recognized by the International Dairy Federation,[3] over 400 identified by Walter and Hargrove, over 500 by Burkhalter, and over 1,000 by Sandine and Elliker.[5] Some attempts have been made to rationalise the classification of cheese; a scheme was proposed by Pieter Walstra that uses the primary and secondary starter combined with moisture content, and Walter and Hargrove suggested classifying by production methods. This last scheme results in 18 types, which are then further grouped by moisture content.[3]

Source of milk

[edit]Cheeses may be categorized by the source of the milk used to produce them. While most of the world's commercially available cheese is made from cow's milk, many parts of the world also produce cheese from goats and sheep. Examples include Roquefort (produced in France) and pecorino (produced in Italy) from ewe's milk.[6] One farm in Sweden also produces cheese from moose's milk (known as 'elk' in Europe).[7]

Sometimes cheeses marketed under the same name are made from milk of different species—feta cheeses, for example, are made in Greece from either sheep's milk, or a combination of sheep and goat's milk.[8] Queso añejo cheese is traditionally made with goat milk, but in the modern era is generally made with cow's milk.[9]

Cheeses are also labeled based on the added fat content of the milk from which they are produced. Double cream cheeses are soft cheeses of cows' milk enriched with cream so that their fat in dry matter (FDM or FiDM) content is 60–75%; triple cream cheeses are enriched to at least 75%.[10]

Moisture: soft to hard

[edit]Categorizing cheeses by moisture content or firmness is a common but inexact practice. Harder cheeses have a lower moisture content than softer cheese, as they are generally packed into molds under more pressure and aged for a longer time than the soft cheeses. The lines between soft, semi-soft, semi-hard, and hard are often classified by a metric based on the weight of the moisture content of the cheese as a division of its dry weight minus the weight of the fat content in the cheese.[11] Other factors than moisture have a role in the firmness of the cheese; a higher fat content tends to result in a softer cheese, as fat interferes with the protein network that provides structure, other significant factors include PH level and salt content.[12][13][14]

Soft cheese

[edit]

Soft cheeses include soft-ripened cheeses, some blue cheeses, some pasta filata cheeses, and fresh cheeses. They are often spreadable, but do not generally melt or brown well.[15] Soft cheese are generally produced in a cool and humid environment and tend to have very short maturation periods: cream cheeses, which are not matured; Brie and Neufchâtel that mature for no more than a month, and Neufchâtel which can be sold after 10 days of maturation.[16][17]

The higher moisture content of soft cheeses will mean they spoil faster than hard cheeses and are kept at low temperatures to delay spoiling.[18]

The moisture content of soft cheeses is between 55–80% of its dry weight.[19]

Semi-soft cheese

[edit]

Semi-soft cheeses, and the sub-group Monastery cheeses, have a high moisture content, smooth and creamy interior, and a washed rind.[20][21][22] Well-known varieties include Mozzarella, Havarti, Munster, Port Salut, Jarlsberg, and Butterkäse. Many blue cheeses are semi-soft. [15]

The moisture content of semi-soft cheeses is between 42–55% of its dry weight.[19]

Semi-hard cheese

[edit]

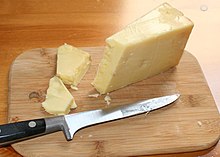

Semi-hard cheeses include the familiar Cheddar, one of a family of semi-hard or hard cheeses (including Cheshire and Gloucester), whose curd is cut, gently heated, piled, and stirred before being pressed into forms. Colby and Monterey Jack are similar but milder cheeses; their curd is rinsed before it is pressed, washing away some acidity and calcium. Certain Swiss-style cheesese, such as Emmental (often called "Swiss cheese" in the US), may be semi-hard. The same bacteria that give such cheeses their eyes also contribute to their aromatic and sharp flavours. Other semi-soft to firm cheeses include Cantal and Kashkaval/Cașcaval.

Cheeses of this type are often considered as lending themselves to melting in culinary preparation.[23]

The moisture content of semi-hard cheeses is between 45–50% of its dry weight.[19]

Hard cheese

[edit]

Hard cheeses are packed tightly into forms (usually wheels) and aged for months or years until their moisture content is significantly less than half of their weight, leading to a firm and granular texture. Most of the whey is removed before pressing the curd.

Hard cheeses are often consumed in grated form, and include Grana Padano, Parmesan, or pecorino. The flavour of hard cheeses is often perceived to be richer.[24][25]

The moisture content of semi-hard cheeses is between 25–45% of its dry weight.[19]

Mold

[edit]

There are three main categories of cheese in which the presence of mold is an important feature: soft-ripened cheeses, washed-rind cheeses and blue cheeses.[26]

Soft-ripened

[edit]Soft-ripened cheeses begin firm and rather chalky in texture, but are aged from the exterior inwards by exposing them to mold. The mold may be a velvety bloom of P. camemberti that forms a flexible white crust and contributes to the smooth, runny, or gooey textures and more intense flavours of these aged cheeses.[26]

Brie and Camembert, the most famous of these cheeses, are made by allowing white mold to grow on the outside of a soft cheese for a few days or weeks.[26]

Washed-rind

[edit]Washed-rind cheeses are soft in character and ripen inwards like those with white molds; however, they are treated differently. Washed-rind cheeses are periodically cured in a solution of saltwater brine or mold-bearing agents that may include beer, wine, brandy and spices, making their surfaces amenable to a class of bacteria (Brevibacterium linens, the reddish-orange smear bacteria) that impart pungent odors and distinctive flavours and produce a firm, flavourful rind around the cheese.[27] Washed-rind cheeses can be soft (Limburger), semi-hard, or hard (Appenzeller). The same bacteria can also have some effect on cheeses that are simply ripened in humid conditions, like Camembert. The process requires regular washings, particularly in the early stages of production, making it quite labor-intensive compared to other methods of cheese production.[28]

Smear-ripened

[edit]S-rind cheeses are also smear-ripened with solutions of bacteria or fungi (most commonly Brevibacterium linens, Debaryomyces hansenii or Geotrichum candidum[29]), which usually gives them a stronger flavor as the cheese matures.[29] In some cases, older cheeses are smeared on young cheeses to transfer the microorganisms. Many, but not all, of these cheeses have a distinctive pinkish or orange coloring of the exterior. Unlike with other washed-rind cheeses, the washing is done to ensure uniform growth of desired bacteria or fungi and to prevent the growth of undesired molds.[30] Examples of smear-ripened cheeses include Munster and Port Salut.

Blue

[edit]So-called blue cheese is created by inoculating a cheese with Penicillium roqueforti or Penicillium glaucum. This is done while the cheese is still in the form of loosely pressed curds, and may be further enhanced by piercing a ripening block of cheese with skewers in an atmosphere in which the mold is prevalent. The mold grows within the cheese as it ages. These cheeses have distinct blue veins, which gives them their name and, often, assertive flavours. The molds range from pale green to dark blue, and may be accompanied by white and crusty brown molds.[31][32] Their texture can be soft or firm.[33] Some of the most renowned cheeses in this type include Roquefort, Gorgonzola and Stilton.

Fresh and whey cheeses

[edit]

The main factor in categorizing these cheeses is age. Fresh cheeses without additional preservatives can spoil in a matter of days.[34]

For these simplest cheeses, milk is curdled and drained, with little other processing. Examples include cottage cheese, cream cheese, curd cheese, farmer cheese, caș, chhena, fromage blanc, queso fresco, paneer, fresh goat's milk chèvre, Breingen-Tortoille, Irish Mellieriem Rochers and Belgian Mellieriem Rochers. Such cheeses are often soft and spreadable, with a mild flavour.[35]

Whey cheeses are fresh cheeses made from whey, a by-product from the process of producing other cheeses which would otherwise be discarded. Corsican brocciu, Italian ricotta, Romanian urda, Greek mizithra, Croatian skuta, Cypriot anari cheese, Himalayan chhurpi and Norwegian Brunost are examples. Brocciu is mostly eaten fresh, and is as such a major ingredient in Corsican cuisine, but it can also be found in an aged form.[36]

Some fresh cheeses such as fromage blanc and fromage frais (the latter differing from the former in that it contains live cultures) are commonly sold and consumed as desserts.[37][38]

Stretched curd cheeses

[edit]Stretched curd, for which the Italian term pasta filata is often used, is a group of cheeses where the hot curd is stretched, today normally mechanically, producing various effects.[39] Many traditional pasta filata cheeses such as the Italian mozzarella and halloumi from the Eastern Mediterranean also fall into the fresh cheese category. Fresh curds are stretched and kneaded in hot water to form a ball of mozzarella, which in southern Italy is usually eaten within a few hours of being made. Stored in brine, it can easily be shipped, and it is known worldwide for its use on pizza. But not all stretch-curd cheeses are fresh; the Italian provolone, Ragusano, caciocavallo and many others are hard or semi-hard, and aged. Oaxaca cheese from Mexico is semi-hard, but not aged. Like the pressed cooked cheeses (below), all these are made using thermophilic lactic fermentation starters.[40] Many of the various types of string cheese are made this way.[citation needed]

Cooked pressed cheeses

[edit]

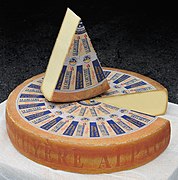

Swiss-type cheeses, also known as Alpine cheeses, are a group of hard or semi-hard cheeses with a distinct character, whose origins lie in the Alps of Europe, although they are now eaten and imitated in most cheesemaking parts of the world. They are classified as "cooked", meaning made using thermophilic lactic fermentation starters, incubating the curd with a period at a high temperature of 45°C or more.[41] Since they are later pressed to expel excess moisture, the group are also described as "'cooked pressed cheeses'",[42] fromages à pâte pressée cuite in French. Their distinct character arose from the requirements of cheese made in the summer on high Alpine grasslands (alpage in French), and then transported with the cows down to the valleys in the winter, in the historic culture of Alpine transhumance. Traditionally the cheeses were made in large rounds or "wheels" with a hard rind, and were robust enough for both keeping and transporting.[43]

The best known cheeses of the type, all made from cow's milk, include the Swiss Emmental, Gruyère and Appenzeller, as well as the French Beaufort and Comté (from the Jura Mountains, near the Alps). Both countries have many other traditional varieties, as do the Alpine regions of Austria (Alpkäse) and Italy (Asiago), though these have not achieved the same degree of intercontinental fame.[44] Most global modern production is industrial, and usually made in rectangular blocks, and by wrapping in plastic no rind is allowed to form. Historical production was all with "raw" milk, although the periods of high heat in making largely controlled unwelcome bacteria, but modern production may use thermized or pasteurized milk.[45]

The general eating characteristics of the Alpine cheeses are a firm but still elastic texture, flavor that is not sharp, acidic or salty, but rather nutty and buttery. When melted, which they often are in cooking, they are "gooey", and "slick, stretchy and runny".[46]

Another related group of cooked pressed cheeses is the very hard Italian "grana" cheeses; the best known are Parmesan and Grana Padano. Although their origins lie in the flat and (originally) swampy Po Valley, they share the broad Alpine cheesemaking process, and began after local monasteries initiated drainage programmes from the 11th century onwards. These were Benedictine and Cistercian monasteries, both with sister-houses benefiting from Alpine cheesemaking. They seem to have borrowed their techniques from them, but produced very different cheeses, using much more salt, and less heating, which suited the local availability of materials.[47]

Brined

[edit]

Brined or pickled cheese is matured in a solution of brine in an airtight or semi-permeable container. This process gives the cheese good stability, inhibiting bacterial growth even in hot environments.[48] Brined cheeses may be soft or hard, varying in moisture content, and in color and flavor, according to the type of milk used. All will be rindless, and generally taste clean, salty and acidic when fresh, developing some piquancy when aged, and most will be white.[48] Varieties of brined cheese include bryndza, feta, halloumi, sirene, and telemea.[48] Brined cheese is the main type of cheese produced and eaten in the Middle East and Mediterranean areas.[49]

Processed

[edit]Processed cheese is made from traditional cheese and emulsifying salts, often with the addition of milk, more salt, preservatives, and food coloring. Its texture is consistent, and it melts smoothly. It is sold packaged and either pre-sliced or unsliced, in several varieties. Some are sold as sausage-like logs and chipolatas (mostly in Germany and the US), and some are molded into the shape of animals and objects. Some, if not most, varieties of processed cheese are made using a combination of real cheese waste (which is steam-cleaned, boiled and further processed), whey powders, and various mixtures of vegetable oils, palm oils or fats. Processed cheese is constituted with other ingredients such as milk proteins, emulsifiers, and flavorings; meaning the cheese content may be significantly less than 100%. The US Food and Drug Administration stipulates that a food product must contain at least 51% of actual cheese content to be labelled as a cheese.[50][51][52][53]

Gallery

[edit]- Some major types of cheese

-

Brie – (France)

-

Bleu de Gex – (France)

-

Camembert – (France)

-

Chabichou du Poitou – (France)

-

Cheddar – (United Kingdom, England)

-

Cœur de Neufchâtel – (France)

-

Comté – (France)

-

Edam – (Netherlands)

-

Emmental – (Switzerland)

-

Fourme d'Ambert – (France)

-

Gruyère – (Switzerland)

-

Langres – (France)

-

Maroilles – (France)

-

Mozzarella – (Italy)

-

Parmigiano-Reggiano – (Italy)

-

Reblochon – (France)

-

Ricotta – (Italy)

-

Rigotte de Condrieu – (France)

-

Sainte-Maure de Touraine – (France)

-

Saint-Pierre – (France)

-

Blue Stilton – (United Kingdom)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Classification of cheese types using calcium and pH". dairyscience.info. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Barbara Ensrud, (1981) The Pocket Guide to Cheese, Lansdowne Press/Quarto Marketing Ltd., ISBN 0-7018-1483-7

- ^ a b c Fox, Patrick F.; Guinee, Timothy P.; Cogan, Timothy M.; McSweeney, Paul L. H. (2000). "Principal Families of Cheese". Fundamentals of cheese science. Aspen Publishers. p. 388. ISBN 9780834212602.

- ^ "Classification of Cheese". egr.msu.edu. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Patrick F. Fox (28 February 1999). Cheese: chemistry, physics and microbiology, Volume 1. Springer, 1999. p. 1. ISBN 9780834213388. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "Know Your Milk". Schuman Cheese. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Knelly, Clarice (13 September 2022). "The Only Place On Earth That Produces Genuine Moose Cheese". Tasting Table. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "Feta PDO - European Commission". agriculture.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ CooksInfo. "Añejo Cheese". CooksInfo. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "What are Double and Triple Crème Cheeses?". The Cheese Professor. 14 December 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ "IDF Factsheet Cheese and Varieties Part II: Cheese Styles" (PDF). fil-idf.org. 18 January 2021.

- ^ "Measuring the Role of pH and Acidity in Cheese with Starter Cultures". cheeseforthought.com. 2 September 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Kincaid, Jonah (10 October 2024). "Science Behind Cheese Maturation (How Affinage Crafts Cheese)". Cheese Scientist. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Whitehead, H. R. (1 August 1948). "372. Control of the moisture content and 'body-firmness' of cheddar cheese". Journal of Dairy Research. 15 (3): 387–397. doi:10.1017/S0022029900005185. ISSN 1469-7629.

- ^ a b "Types of Cheese Texture". The Wisconsin Cheeseman.

- ^ ibex (2 February 2015). "Cheese Ageing – how to mature and look after cheese". The Courtyard Dairy. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Blog - Cheese maturing process Serowar". serowar.eu. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Brady, Greg (22 June 2021). "The Art Of Cheese Maturation". The Cheese Lover. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ a b c d Zheng, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, B. (29 July 2021). "A Review on the General Cheese Processing Technology, Flavor Biochemical Pathways and the Influence of Yeasts in Cheese". Frontiers in Microbiology. 12. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.703284. PMC 8358398. PMID 34394049.

- ^ "The Catholic monasteries that invented our favorite cheeses". Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ "Monastery Cheeses". www.cheese.com. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ Ditaranto, Jamie (20 September 2014). "Cheese Devotees: All About Monastic Cheeses". culture: the word on cheese. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

- ^ "Everything you need to know about Semi-Hard Cheese | Castello | Castello®️". www.castellocheese.com. Retrieved 6 January 2025.

- ^ "Discover the 10 Hard Cheeses Everyone Should Know - Love Cheese". Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Hard cheese| Everything you need to know about Hard cheese | Castello | Castello®️". www.castellocheese.com. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ a b c "cheese – soft-ripened and blue-vein – The Book of Threes". 14 September 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Washed Rind Cheese Archived 22 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine at Practically Edible Food Encyclopedia

- ^ Clare (12 May 2018). "What is a washed rind cheese – how are they made, what are the benefits?". Saucy Dressings. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ a b Fox, Patrick. Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. p. 199.

- ^ Fox, Patrick. Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology. p. 200.

- ^ "The Curious Origins Of Blue Cheese: A History Unveiled - Taste Pursuits". tastepursuits.com. 5 February 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "What is Penicillium Roqueforti?". anycheese.com. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ Emma (10 March 2024). "How is Blue Cheese Made: The Art of Culturing Mold-Infused Cheese". Your Cheese Friend. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions - Cheese Making Pot - Shelf Life Of Blue Cheese | The Cheesemaker". www.thecheesemaker.com. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "The Many Varieties of Fresh Cheese". The Spruce Eats. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ "Brocciu Cheese - itscheese.com cheese guide". itscheese.com. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ LLC, New York Media (22 October 1990). New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC.

- ^ Hastings, Chester (18 March 2014). The Cheesemonger's Seasons: Recipes for Enjoying Cheese with Ripe Fruits and Vegetables. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-3554-0.

- ^ Lortal, 293

- ^ Lortal, 291–292

- ^ Lortal, 291–292

- ^ Thorpe, 266

- ^ Donnelley, 3–5; Thorpe, 262–268; Oxford, 15–19

- ^ Lortal, 291–292; Thorpe, 266; Oxford, 16, 19, 46–48 (Asiago), 50–51 (Austria), 345

- ^ Oxford, 34–35

- ^ Thorpe, 266–267; Donnelley, 3–5

- ^ Kindstedt, 155–156

- ^ a b c A. Y. Tamime (15 April 2008). Brined cheeses. John Wiley & Sons. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4051-7164-9.

- ^ A. Y. Tamime; R. K. Robinson (1991). Feta and Related Cheeses. Woodhead Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 1845698223.

- ^ Myers, Dan (15 June 2017). "Before You Unwrap That Kraft Single, Here's What You Should Know". The Daily Meal. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Team, The Cell Health (30 May 2023). "Behind the Kraft Singles Phenomenon: Not Really Cheese". Cell Health News. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "What's really in a packet of processed cheese slices?". The Irish Times. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Delany, Alex (25 April 2018). "What Is Processed Cheese, and Should We Eat It?". Bon Appétit. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

References

[edit]- Donnelley, Catherine W. (ed), Cheese and Microbes, 2014, ASM Press, ISBN 1555818595, 9781555818593, google books

- Fox, P.H., ed., Fundamentals of Cheese Science, 2000, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 0834212609, 9780834212602, google books

- Kinstedt, Paul, Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization, 2012, Chelsea Green Publishing, ISBN 1603584129, 9781603584128, google books

- Lortal, Sylvie, "Cheeses made with Thermophilic Lactic Starters", Chapter 16 in Handbook of Food and Beverage Fermentation Technology, 2004, CRC Press, ISBN 0203913558, 9780203913550, google books

- "Oxford": Donnelley, Catherine W. (ed), The Oxford Companion to Cheese, 2016, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199330883, 9780199330881, google books

- Thorpe, Liz, The Book of Cheese: The Essential Guide to Discovering Cheeses You'll Love, 2017, Flatiron Books, ISBN 1250063469, 9781250063465, google books