Indigenous peoples in Bolivia

Bolivianos Nativos (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Predominantly in the Andean Plateau, the Gran Chaco and Amazon Rainforest | |

| 1,474,654[1] | |

| 835,535[1] | |

| 572,314[1] | |

| 521,814[1] | |

| 289,728[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish • Indigenous languages (including Quechua, Aymara, Guarani, Chiquitano) | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Catholicism Minority: Indigenous religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indigenous peoples of the Americas | |

The Indigenous peoples in Bolivia or Native Bolivians (Spanish: Bolivianos Nativos) are Bolivians who have predominantly or total Amerindian ancestry. They constitute anywhere from 20 to 60% of Bolivia's population of 11,306,341,[2][better source needed] depending on different estimates, and depending notably on the choice Mestizo being available as an answer in a given census, in which case the majority of the population identify as mestizo,[2][better source needed] and they belong to 36 recognized ethnic groups. Aymara and Quechua are the largest groups.[3] The geography of Bolivia includes the Andes, the Gran Chaco, the Yungas, the Chiquitania and the Amazon Rainforest.

An additional 30–68% of the population is mestizo, having mixed European and Indigenous ancestry.[2][better source needed]

Lands

[edit]

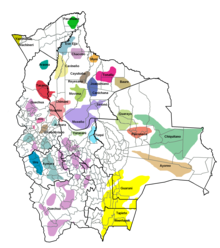

Lands collectively held by Indigenous Bolivians are Native Community Lands or Tierras Comunitarias de Origen (TCOs). These lands encompass 11 million hectares,[3] and include communities such as Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Natural Area, Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory, Pilón Lajas Biosphere Reserve and Communal Lands, and the Yuki-Ichilo River Native Community Lands.

Rights

[edit]

In 1991, the Bolivian government signed the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989, a major binding international convention protecting Indigenous rights. On 7 November 2007, the government passed Law No. 3760 which approved of UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.[3]

In 1993, the Law of Constitutional Reform recognized Indigenous rights.[4]

Social protests and political mobilization

[edit]Revolution: 1952

[edit]Historically Indigenous people in Bolivia suffered many years of marginalization and a lack of representation.[4] However, the late 20th century saw a surge of political and social mobilization in Indigenous communities.[4] The 1952 Bolivian National Revolution that liberated Bolivians and gave Indigenous peoples citizenship still gave little political representation to Indigenous communities.[4] It was in the 1960s and 1970s that social movements such as the Kataraista movement began to also include Indigenous concerns.[4] The Katarista movement, consisting of the Aymara communities of La Paz and the Altiplano, attempted to mobilize the Indigenous community and pursue an Indigenous political identity through mainstream politics and life.[5] Although the Katarista movement failed to create a national political party, the movement influenced many peasant unions such as the Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia (Unified Syndical Confederation of Peasant Workers of Bolivia).[4] The Katarista movement of the 1970s and 1980s died out by the end of the decade; however, many of the same concerns rose again in the 1990s.[4]

Social movement: 1990s and 2000s

[edit]The 1990s saw a large surge of political mobilization for Indigenous communities.[4] President Sánchez de Lozada passed reforms such as the 1993 Law of Constitutional Reform to acknowledge Indigenous rights in Bolivian culture and society. However, many of these reforms fell short as the government continued to pass destructive environmental and anti-indigenous rules and regulations.[4] A year after the 1993 Law of Constitutional Reform passed recognizing Indigenous rights, the 1994 Law of Popular Participation decentralized political structures, giving municipal and local governments more political autonomy.[4] Two years later the 1996 Electoral Law greater expanded Indigenous political rights as the national congress transitioned into a hybrid proportional system, increasing the number of Indigenous representatives.[4]

Environmental injustice became a polarizing issue as many Indigenous communities protested against government-backed privatization and eradication of natural resources and landscapes.[6] Coca leaf production is an important sector of the Bolivian economy and culture, especially for campesinos and Indigenous peoples.[7] The eradication of coca production, highly supported by the U.S. and its war on drugs and the Bolivian government spurred heavy protests by the Indigenous community.[6] One of the main leaders of the coca leaf movement, Evo Morales, became a vocal opponent against state efforts to eradicate coca. The coca leaf tensions began in the region of Chapare in 2000 and became violent as protests against police officials and residents began. During this time protestors organized road blockades, and traffic stops to protest low prices.[8] Coca leaf producers continued to resist the government's policies on production further devaluing the peso and seized control of the peasant confederation (Confederación Sindical Única de Trabajadores Campesinos de Bolivia).[9] With Evo Morales' leadership, the cocaceleros were able to form coalitions with other social groups and eventually create a political party, the Movement Towards Socialism (MAS).[7]

Similarly, the 2000 Water War bought these protests to national attention.[10] The Water War began in the city of Cochabamba, where the private company Bechtel began to increase rates for water after the government contracted out to privatize Cochabamba's water system.[10] When Cochabamba's residents realized they could not afford to pay for this resource, they began to protest in alliance with urban workers, rural peasants and students.[9] The mass protest resulted in a state of emergency as clashes against the police and protestors became more violent.[5] The protests were largely successful and resulted in the reversal of the privatization.[5]

Additionally in 2003, as reliance on natural resources in Bolivia's economy grew, resistance came from Bolivia's Indigenous community in the form of the Gas Wars.[11] This conflict, which grew from the Water Wars, united coca farmers, unions and citizens to protest the sale of Bolivia's gas reserves to the United States through the port of Chile.[10] Again, Indigenous peoples participated alongside miners, teachers and ordinary citizens through road blockades and the disruption of traffic.[10] Political protests for social and economic reforms have been a consistent method for Indigenous mobilization and inclusion in the political process.[10] They have concluded in successful results and created a platform for Indigenous rights. The protest movements soon paved the way for legal and political changes and representation.

Indigenous march in 2011

In 2011 Bolivian Indigenous activists started a long protest march from the Amazon plains to the country's capital, against a government plan to build a 306 km (190 mi) highway through a national park in Indigenous territory.[12]

The subcentral Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS), the Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia (CIDOB), and the highland Indigenous confederation National Council of Ayllus and Markas of Qullasuyu (CONAMAQ)—supported by other indigenous and environmental groups—organized a march from Trinidad, Beni, to the national capital La Paz in opposition to the project, beginning on 15 August 2011.[13]

"One of the latest tactics deployed by governments to bypass Indigenous contestation is to consult non-[local] Indigenous communities. This happened to communities in the case of the road project through Bolivia's Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS)." International pressure built up after Evo Morales' government violently repressed a large Indigenous march against a road project in "the massacre of Chaparina".[14]

This led to the Chaparina Massacre—on 25 September 2011, national police brutally repressed Indigenous marchers protesting the construction of a government-proposed highway through the TIPNIS Indigenous territory and national park.[15]

Evo Morales and the plurinational state

[edit]One of the biggest successes for Bolivia's Indigenous community was the election of Evo Morales, former leader of the cocaleros and Bolivia's first Indigenous president.[16] President Morales attempted to establish a plurinational and postcolonial state to expand the collective rights of the Indigenous community.[17] The 2009 constitution recognized the presence of the different communities that reside in Bolivia and gave Indigenous peoples the right of self-governance and autonomy over their ancestral territories.[17] Expanding on the Constitution, the 2010 Framework Law of Autonomies and Decentralization outlined the legal rules and procedures that Indigenous communities must take to receive autonomy.[16] Through these decentralization efforts, Bolivia became the first plurinational state in South America.[18] However, many Indigenous communities claim that the process to receive autonomy is inefficient and lengthy.[17] Along with Indigenous concerns, there are internal issues and competing interests between Bolivia's restrictive legal framework, liberal policies and the concept of Indigenous self-governance.[16] Nonetheless, the addition of subautonomies in Bolivia's government has made strides in including Indigenous communities in the political process.

Achievements

[edit]

In 2015 Bolivians made history again by selecting the first Indigenous president of the Supreme Court of Justice, Justice Pastor Cristina Mamani.[citation needed] Mamani is a lawyer from the Bolivian highlands from the Aymara community.[19] She won the election with the most votes.[19] The Supreme Court of Justice is made up of nine members and nine alternative justices, each representing the nine departments in Bolivia.[20] The justices are elected in popular nonpartisan elections with terms of six years.[20]

Groups

[edit]Precolumbian cultures

[edit]- Tiwanaku, AD 300–1000

- Mollo culture, AD 1000–1500

- Lupaca

- Charca people

- Payaguá people

- Uru-Murato

Contemporary groups

[edit]- Araona (Cavina)[21]

- Aymara, Andes[21]

- Ayoreo, Gran Chaco[21]

- Baure, Beni Department[21]

- Borôro, Santa Cruz Department[21]

- Callawalla, Andes[21]

- Canichana (Kanichana), lowlands[21]

- Cavineños, northern Bolivia[21]

- Cayubaba (Cayuvava, Cayuwaba), Beni Department[21]

- Chácobo, northwest Beni Department[21]

- Chané (Izoceño), Santa Cruz Department

- Chipaya (Puquina), Oruro Department[21]

- Chiquitano (Chiquito, Tarapecosi), Santa Cruz Department[21]

- Ese Ejja (Ese Exa, Huarayo, Tiatinagua), northwest Bolivia[21]

- Guaraní, Eastern Bolivian Guarani or Chiriguano[21]

- Guarayu[21]

- Guató

- Ignaciano (Moxo), Beni[21]

- Itene (Iteneo, Itenez), Beni[21]

- Itonama (Machoto, Saramo)[21]

- Kolla

- Jorá (Hora)[21]

- Leco (Rik’a), east Lake Titicaca[21]

- Machinere (Maxinéri), Pando Department[21]

- Movima, Beni[21]

- Nivaclé, Ashlushlay, Axluslay, Chulupí, Gran Chaco

- Pacahuara (Pacawara), Beni[21]

- Paunaka (Pauna), Ñuflo de Suarez[21]

- Pauserna (Guarayu-Ta, Paucerne, Pauserna-Guarasugwé), Beni[21]

- Quechua (Kichua), Bolivia[21]

- Reyesano (Maropa, San Borjano), Beni[21]

- Saraveca, Santa Cruz[21]

- Shinabo (Mbia Chee, Mbya)[21]

- Sirionó (Miá), Beni and Santa Cruz[21]

- Tacana (Takana), La Paz Department[21]

- Tapieté (Guasurango, Ñanagua, Tirumbae, Yanaigua), Tarija Department[21]

- Toba (Qom), Tarija Department[21]

- Toromona (Toromono), La Paz Department[21]

- Trinitario (Mojos, Moxos), Beni[21]

- Tsimané (Chimané, Mosetén), Beni[21]

- Uru (Iru-Itu, Morato, Muratu), Oruro Department[21]

- Wichí (Noctén, Noctenes, Oktenai, Weenhayek), Tarija Department[21]

- Yaminawá (Jaminawa, Yamanawa, Yaminahua), Pando Department[21]

- Yuqui (Bia, Yuki)[21]

- Yuracare (Yura), Beni and Cochabamba Departments[21]

See also

[edit]- Demographics of Bolivia

- Mestizos in Bolivia

- White Bolivians

- Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of Bolivia

- Andean music

- Andean textiles

- Ekeko, Andean god of abundance

- El Fuerte de Samaipata, archeological site

- Guarani mythology

- History of Bolivian nationality

- Kallawaya, traditional healers

- Yanantin, complementary dualism in Andean philosophy

Bibliography

[edit]- Ossio Acuña, Juan M. Ideología mesiánica del mundo andino. Ignacio Prado Pastor.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Características de la Población – Censo 2012" [Population Characteristics – 2012 Census] (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística. p. 103. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2021. Excluding Afro-Bolivians (23,330).

- ^ a b c "CIA - The World Factbook -- Bolivia". CIA. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ^ a b c "Indigenous peoples in Bolivia." International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. Retrieved 2 Dec 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Brysk, Alison; Bennett, Natasha (2012). "Voice in the Village: Indigenous Peoples Contest Globalization in Bolivia". The Brown Journal of World Affairs. 18 (2): 115–127. JSTOR 24590867.

- ^ a b c Salt, Sandra (2006). "Towards Hegemony: The Rise of Bolivia's Indigenous Movements" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Healy, Kevin (1991). "Political Ascent of Bolivia's Peasant Coca Leaf Producers". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 33 (1): 87–121. doi:10.2307/166043. JSTOR 166043.

- ^ a b Mahler, John (September 2013). "The Scale Shift of Cocelero Movements in Peru and Bolivia" (PDF). Calhoun: International Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School.

- ^ Schaefer, Timo (2009). "Engaging Modernity: The Politicai Making of Indigenous Movements in Bolivia and Ecuador, 1900-2008". Third World Quarterly. 30 (2): 397–413. doi:10.1080/01436590802681116. JSTOR 40388122. S2CID 154341239.

- ^ a b Shoaei, Maral (2012). MAS and the Indigenous People of Bolivia (MA thesis). University of South Florida – via Scholar Commons.

- ^ a b c d e Arce, Moisés; Rice, Roberta (2009). "Societal Protest in Post-Stabilization Bolivia". Latin American Research Review. 44 (1): 88–101. doi:10.1353/lar.0.0071. JSTOR 20488170. S2CID 144317703.

- ^ FABRICANT, NICOLE (2012). "Sediments of History". Mobilizing Bolivia's Displaced: Indigenous Politics and the Struggle over Land. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 17–44. doi:10.5149/9780807837511_fabricant.6. ISBN 9780807872499. JSTOR 10.5149/9780807837511_fabricant.6.

- ^ "Bolivians March Against Development Plan". Aljazeera. 16 Aug 2011.

- ^ "Bolivia Amazon protesters resume Tipnis road march". BBC. 1 Oct 2011.

- ^ Picq, Manuela (22 Dec 2012). "The Failure to Consult Triggers Indigenous Creativity". Aljazeera.

- ^ Achtenburg, Emily (21 Nov 2013). "Bolivia: Two Years after Chaparina Still No Answers". NACLA.

- ^ a b c Tockman, Jason; Cameron, John; Plata, Wilfredo (2015). "New Institutions of Indigenous Self-Governance in Bolivia: Between Autonomy and Self-Discipline". Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies. 10: 37–59. doi:10.1080/17442222.2015.1034442. S2CID 5722035.

- ^ a b c Tockman, Jason; Cameron, John (2014). "Indigenous Autonomy and the Contradictions of Plurinationalism in Bolivia". Latin American Politics and Society. 56 (3): 46–69. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2014.00239.x. JSTOR 43284913. S2CID 146457127.

- ^ Elliot-Meisel, Emily (Spring 2014). "Rural Indigenous Autonomy: A Case of Decentralization in Bolivia".

- ^ a b "Bolivia's New Faces of Justice". NACLA. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ a b "Bolivia - The Judiciary". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2018-11-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao "Languages of Bolivia." Ethnologue. Retrieved 2 Dec 2013.