Nicholas Trist

Nicholas Trist | |

|---|---|

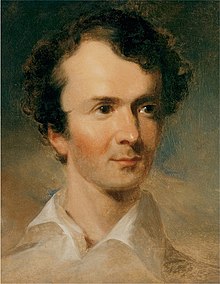

Portrait by John Neagle, in 1835 | |

| 16th Chief Clerk of the Department of State | |

| In office August 28, 1845 – April 14, 1847 | |

| President | James K. Polk |

| Preceded by | William S. Derrick |

| Succeeded by | William S. Derrick |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Nicholas Trist June 2, 1800 Charlottesville, Virginia |

| Died | February 11, 1874 (aged 73) Alexandria, Virginia |

| Resting place | Ivy Hill Cemetery (Alexandria, Virginia)[1] |

| Education | United States Military Academy (did not graduate) |

| Known for | Negotiations for the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo |

| Signature | |

Nicholas Philip Trist (June 2, 1800 – February 11, 1874) was an American lawyer, diplomat, planter, and businessman. Even though he had been dismissed by President James K. Polk as the negotiator with the Mexican government, he negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which ended the Mexican–American War. The U.S. conquered Mexican territory and vastly expanded the United States. All or part of ten current states were carved out of former Mexican territory.

Early years

[edit]Trist was born in Charlottesville, Virginia. He was the son of Hore Browse Trist, a lawyer, and Mary Brown. His grandfather was from England, while his grandmother, Elizabeth House Trist, was an acquaintance of Thomas Jefferson.[2][3] Trist attended West Point but did not graduate and then studied law under Thomas Jefferson. Trist served as Jefferson's personal secretary in the 1820s and became an executor of his estate.[4]

Trist married Virginia Jefferson Randolph, Thomas Jefferson's granddaughter, on September 11, 1824. They had three children, Martha Jefferson Trist Burke (1826–1915), Thomas Jefferson Trist (1828–1890), and Hore Browse Trist (1832–1896).[4]

He served as a clerk in the U.S. State Department in 1828–1832, including a one-year assignment in 1831 as private secretary to Andrew Jackson, whom he greatly admired.[5]: 92–93 Trist provided a conduit of communication for James Madison to President Jackson.[6]

Consul in Havana

[edit]Trist was appointed U.S. consul in Havana, Cuba, a Spanish territory at the time, by President Jackson, in which capacity he served from 1833 to 1841. Shortly after arriving there in 1833, Trist invested in a sugar plantation deal that went bad. He made no secret of his pro-slavery views. According to members of a British commission sent to Cuba to investigate violations of the treaty ending the African slave trade, Trist became involved in the creation of false documents designed to mask illegal sales of Africans into bondage. For a time Trist also served as the consul in Cuba for Portugal, another country whose nationals were active in the illegal slave trade.[5]: 93

As consul, Trist became unpopular with New England ship captains who believed he was more interested in maintaining good relations with Cuban officials than defending their interests. Captains and merchants pressed members of Congress for Trist's removal. In late 1838 or early 1839, the British commissioner Dr. Richard Robert Madden wrote U.S. abolitionists about Trist's misuse of his post to promote slavery and earn fees from the fraudulent document schemes. A pamphlet detailing Madden's charges was published shortly before the beginning of the sensational Amistad affair, when Africans sold into slavery in Cuba managed to seize control of the schooner in which they were being transported from Havana to provincial plantations. Madden travelled to the United States, where he gave expert testimony in the trial of the Amistad Africans, explaining how false documents were used to make it appear the Africans were Cuban-born slaves.[7]

This exposure of the activities of the U.S. Consul General, coupled with the complaints of ship captains, caused a Congressional investigation and eventual recall of Trist in 1840. Neither Trist nor Madden is depicted in the film Amistad directed by Steven Spielberg, although there are brief Cuba scenes that suggest how the illegal slave trade was carried on there.

Mexican–American War negotiator

[edit]Trist remained in Cuba until 1845, when President James K. Polk appointed him as a chief clerk in the State Department.[8] In 1847, during the Mexican–American War, President Polk sent Trist to negotiate with the government of Mexico. He was ordered to arrange an armistice with Mexico wherein the U.S. would offer a restitution up to $30 million U.S. dollars, depending on whether he could obtain Baja California and additional southern territory along with the already planned acquisitions of Alta California, the Nueces Strip, and New Mexico. If he could not obtain Baja California and additional territory to the south, then he was instructed to offer $20 million.[5]: 175 President Polk was unhappy with his envoy's conduct which prompted him to order Trist to return to the United States. General Winfield Scott was also unhappy with Trist's presence in Mexico, although he and Scott quickly reconciled and began a lifelong friendship.[5]: 91 [6]

Trist ignored the order to leave Mexico, and wrote a 65-page letter back to Washington, D.C. explaining his reasons for staying.[9] He capitalized on the opportunity to continue bargaining with Santa Anna offering $15 million. Trist successfully negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848.[10] Trist's negotiation was controversial among expansionist Democrats since he had ignored Polk's instructions and settled on a smaller cession of Mexican territory than many expansionists wanted and felt he could have obtained. A part of this instruction was to specifically include Baja California. As part of the negotiations, Trist drew the line directly west from Yuma to Tijuana/San Diego instead of from Yuma south to the Gulf of California, which left all of Baja California as part of Mexico. Polk was furious, but reluctantly approved the treaty since he wanted to have it signed, sealed, and delivered to Congress during his presidency. Trist later commented on the treaty:

"My feeling of shame as an American was far stronger than the Mexicans' could be."[11]

Later years

[edit]

Upon return to Washington, Trist was immediately fired for his insubordination, and his expenses since the time of the recall order were not paid. After his dismissal, Trist moved to West Chester, Pennsylvania, and then to Philadelphia, where he worked as a railroad clerk and paymaster. Trist finally recovered his expenses in 1871, at the urging of Senator Charles Sumner.[3]

Trist supported Republican Abraham Lincoln for U.S. president in 1860. While the Lincoln administration did not offer Trist any patronage, he did serve as postmaster of Alexandria, Virginia, during the Grant administration.[3]

He died in Alexandria on February 11, 1874, aged 73.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Wilson, Scott (August 17, 2016). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons. McFarland & Company, Inc. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Breslin, Thomas A. (October 5, 2011). The Great Anglo-Celtic Divide in the History of American Foreign Relations. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ a b c d Trist, Nicholas Philip, American National Biography

- ^ a b Nicholas Philip Trist, Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c d Greenberg, Amy. A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico. Vintage Books, 2012.

- ^ a b Brookhiser, Richard (2011). James Madison. New York, NY: Basic Book. ISBN 9780465063802. OCLC 855545032.

- ^ Madden, Richard Robert. The Island of Cuba: Its Resources, Progress, and Prospects, Considered in Relation Especially to the Influence of Its Prosperity on the Interests of the British West India Colonies. London: C. Gilpin, 1849.

- ^ Nicholas Trist (biography and picture), The Civil War

- ^ Potter, David, Don E. Fehrenbacher. The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. Harper Perennial, 1976, p. 3.

- ^ Richard M. Ketchum. The Thankless Task Of Nicholas Trist, American Heritage, August 1970, Volume 21, Issue 5.

- ^ Dale L. Walker. Book review: “Lions of the West: Heroes and Villains of the Westward Expansion,” by Robert Morgan, The Dallas Morning News, October 22, 2011

Further reading

[edit]- Castel, Albert. "The Clerk Who Defied a President: Nicholas Trist's Treaty with Mexico." Virginia Cavalcade 34 (1985): 136–143.

- Drexler, Robert W. Guilty of Making Peace: A Biography of Nicholas P. Trist. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, 1991.

- Nortrup, Jack. "Nicholas Trist's Mission to Mexico: A Reinterpretation." The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 71, No. 3 (Jan., 1968), pp. 321–346.

- Ohrt, Wallace. Defiant Peacemaker: Nicholas Trist in the Mexican War. College Station: Texas A&M Press, 1997.

- Sears, Louis Martin. "Nicholas P. Trist, A Diplomat with Ideals." Mississippi Valley Historical Review11#1 (1924): 85–98. online

External links

[edit]- 1800 births

- 1874 deaths

- 19th-century American diplomats

- American people of English descent

- Lawyers from Alexandria, Virginia

- Businesspeople from Charlottesville, Virginia

- Polk administration personnel

- Personal secretaries to the President of the United States

- 19th-century American politicians

- Chief Clerks of the United States Department of State

- American proslavery activists